Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare two different types of fixation systems used to reattach the greater trochanter after revision or total hip arthroplasty. This is a retrospective review of the results of patients that were treated with the two systems. We reviewed the clinical and radiological records of 35 hips with the Dall-Miles cable grip system (DMCGS) and 42 hips with the pin-sleeve system (PSS); follow-up averaged 24 months (range, 4–54) and 30 months (range, 11–42), respectively. The incidences of unsatisfactory clinical and radiological results in the PSS group was less than half that in the DMCGS group. Significant differences were found between the groups with respect to discomfort, tenderness, pain on motion, cable fragmentation, and bone absorption. Compared with the DMCGS, these results suggest the PSS could be the instrument of choice for re-attachment of the greater trochanter in hip arthroplasty.

Introduction

The Dall-Miles cable grip system (DMCGS) was developed by Dall and Miles in 1983 and has since been used widely for re-attachment of the greater trochanter in hip arthroplasty. This device was designed with a multifilament cable and an H-shaped grip of vitallium to improve fixation and stability. They also showed excellent results, reporting only 1.5% nonunion and 3.1% breakage in 130 hips [6]. According to the reports published later by various investigators, however, DMCGS gave unsatisfactory results with nonunion rates ranging from 8.5% to 37.5% compared to the results of the conventional reattachment [14–16, 18]. Moreover, the implants for fixing the greater trochanter used in combination with this cable is relatively large, and pain and bursitis over the greater trochanter, as well as fragmentation, breakage, and bone absorption around the cable are problematic. Therefore, a new device called the pin-sleeve system (PSS), which is a tension-band wiring system that minimises the extraskeletal exposure, was designed and developed in 1999 [11]. An advantage of PSS is that it ensures bone union by stable fixation because the pin crosses the osteotomy line. Besides easy and secure handling, the smaller size helps prevent soft tissue irritation.

The purpose of our study was to compare the clinical results of the PSS with the DMCGS used to re-attach the greater trochanter after total hip arthroplasty.

Patients and methods

In the Kitasato University Hospital, we performed 77 consecutive re-attachments of the greater trochanter in revision or total hip arthroplasty on 73 patients, all of whom were included in this study. Thirty-five hips in ten males and 23 females were fixed using the DMCGS (Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ) (Fig. 1) between 1994 and 1998, and 42 hips in nine males and 31 females were fixed using the PSS (AI Medic, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2) between 1998 and 2000. All the hips were approached using the traditional single plane transtrochanteric osteotomy procedure in the lateral position for wide surgical exposure with subsequent re-attachment and the same postoperative rehabilitation program. The operations in the two groups were performed by the same senior surgeon (M.I.). For these two surgical groups, the DMCGS and the PSS, the average age at operation was 61.3 years (range, 24–85) and 67 years (range, 24–86), respectively; and the average postoperative follow-up period was 24 months (range, 4–54) and 30 months (range, 11–42), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Refixation at the greater trochanter using the Dall-Miles cable grip system

Fig. 2.

Refixation at the greater trochanter using the pin-sleeve system

In the DMCGS group, 23 hips had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis prior to the primary operation, and six hips had femoral neck fracture, five hips, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, and one hip, rheumatoid arthritis. In the PSS group, 30 hips had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis prior to the primary operation, along with seven hips with aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, four hips with femoral neck fracture, and one hip with rheumatoid arthritis. In the DMCGS group, primary total hip arthroplasty was performed in seven hips and revision total hip arthroplasty in 28 hips. In the PSS group, primary total hip arthroplasty was performed in seven hips, revision total hip arthroplasty in 35 hips, including refixation of nonunion at the greater trochanter in five hips that had re-attachments in the primary operations using the DMCGS.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables or the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorised variables. Throughout the study, a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics in the DMCGS and PSS groups

The clinical results for reattachment of the greater trochanter were evaluated by the degree of discomfort, amount of tenderness and pain on motion. An anterioposterior radiograph of the pelvis was taken immediately after the operation and at every visit during follow-up. Each radiograph after re-attachment of the greater trochanter was also evaluated for nonunion at the greater trochanter, breakage of the cable, fragmentation of the cable, and bone absorption around the cable, grip, and/or sleeve. Breakage of the cable and fragmentation were defined according to Silverton et al. [18]. Breakage of the cable was defined as any separation in continuity of the cable and fragmentation, resulting in loose pieces of metallic debris being released into the surrounding area and/or tissue. No significant differences were observed in the patients’ ages between the two groups (Mann–Whitney U-test, p ≥ 0.05; Table 1). The follow-up time was also compared between the groups (Mann–Whitney U-test, p ≥ 0.05). No significant differences were observed when gender, pre-operative diagnoses, and operations were compared between the groups (Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, and chi-square test with Yates’ correction, p ≥ 0.05; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details of the patients

| Demographics | DMCGS group (n = 35) | PSS group (n = 42) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 61.3 (24–85) | 67 (24–86) | 0.07a |

| Female:male | 24:11 | 32:10 | 0.45b |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Osteoarthritis | 23 | 30 | 0.88c |

| Neck fracture of femoral head | 6 | 4 | |

| Aseptic necrosis | 5 | 7 | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 1 | |

| Operation | |||

| Total hip arthroplasty | 7 | 7 | 0.94c |

| Revision total hip arthroplasty including refixation of nonunion at GT | 28 | 35 | |

DMCGS Dall-Miles cable grip system, PSS pin-sleeve system, GT greater trochanter, N.S. not significant

a Calculated with Mann–Whitney test

b Fisher’s exact test

c Chi-squared test

Clinical evaluation

The incidences of discomfort, tenderness, and pain on motion on the greater trochanter part in the PSS group were less than half that in the DMCGS group. The number of all the items in the clinical evaluation was significantly higher in the DMCGS than in the PSS groups (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical and radiological evaluation in the DMCGS and PSS groups

| Evaluations | DMCGS group (n = 35) (%) | PSS group (n = 42) (%) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical evaluation | |||

| Discomfort at GT | 13 (37.1) | 7 (16.7) | 0.038 |

| Tenderness at GT | 17 (48.6) | 8 (19.0) | 0.006 |

| Pain on motion at GT | 13 (37.1) | 6 (14.3) | 0.02 |

| Radiological evaluation | |||

| Nonunion at GT | 8 (22.9) | 5 (11.9) | 0.166 |

| Breakage of cable | 4 (11.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0.128 |

| Fragmentation from cable | 7 (20.0) | 2 (4.8) | 0.042 |

| Bone absorption around cable, grip, sleeve | 19 (54.3) | 5 (11.9) | <0.001 |

DMCGS Dall-Miles cable grip system, PSS pin-sleeve system, GT greater trochanter

a Fisher’s exact test

Radiological evaluation

The incidence of nonunion in the PSS group decreased to approximately half that in the DMCGS group (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.166; Table 2). All cases of nonunion in both groups were in revision total hip arthroplasties. The appearance rate decreased to approximately one-quarter, with cable breakage (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.128), cable fragmentation (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.042), and bone absorption around cable, grip, and/or sleeve in the PSS group (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001; Table 2). All the cases of cable breakage seen in four hips in the DMCGS group and one hip in the PSS group showed nonunion. Fragmentation always appeared around the grip or sleeve. In two (5.7%) of the seven hips with fragmentation, the fragments had migrated close to the cup (Fig. 2). There were no hips with progressive osteolysis or clinical deterioration. The decrease was statistically significant for the appearance of fragmentation and bone absorption (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05; Table 2). In patients over 65 years old, bone absorption around the cable, grip and/or sleeve was seen in as many as 12 of 17 hips (70.6%) in the DMCGS group compared to only in four of 27 hips (14.8%) in the PSS group.

Discussion

The number of positive clinical evaluation items was high in the DMCGS group, while it decreased significantly in the PSS group. These results indicated that this might be attributable to the size and shape of the grip on the greater trochanter after hip arthroplasty. The DMCGS has a large extraskeletal exposure of the grip and a long end where the cable was cut (Fig. 3). Irritation from these causes a high percentage of inflammation of the surrounding soft tissue, and pain and bursitis on the greater trochanter. In this study, the lower incidence of tenderness in the greater trochanter in the PSS group might be due to the reduced size of the device for crimping the cable passing through the holes in the sleeve. Thus, these features should help to improve operative results, and reduce postoperative pain and bursitis over the greater trochanter.

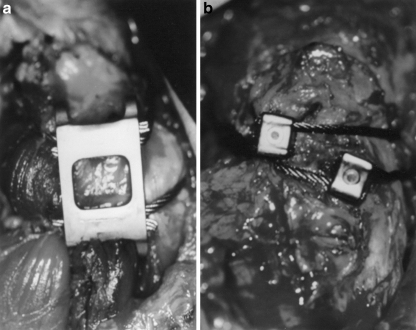

Fig. 3.

Extraskeletal exposure. a The Dall-Miles cable grip system. b The pin-sleeve system

Radiologically, the most important findings in our study were that nonunion, cable breakage, cable fragmentation, and bone absorption around the cable at the greater trochanter occurred frequently in the DMCGS group, phenomena also noted in many other previous studies [2, 4–7, 9, 12, 14–18]. Ritter et al. reported that the cable broke in 32.5% and that nonunion occurred in 37.5% using the stainless steel Dall-Miles cable [16]. They also suggested that the higher incidence of cable breakage could be due to the contact between two different metals, as occurs when the cable and the stem come in contact with each other, possibly leading to corrosion of the metals after emplacement in the femur [16]. Silverton et al. reported that nonunion occurred in 25%, with fraying and fragmentation of the cable seen in 88% of the nonunion group using DMCGS [18]. They also reported that bone absorption around the cable in the area of the lesser trochanter was seen in 10% of the patients. In 12%, large deposits of metallic debris at the inferior border of the acetabulum were seen. McCarthy et al. reported nonunion in 8.5% and that cable breakage occurred in 10.3% [15]. Koyama et al. discovered nonunion in 30.6% and cable breakage in 6.5% of the cases followed for at least one year [14].

In our series, although the incidence of nonunion of the greater trochanter in the PSS cases did not differ significantly from those treated with the DMCGS, nonunion decreased to approximately half. In addition, those patients in whom the DMCGS treatment was converted to the PSS due to unacceptable union were included in our study. The effect of the pin passing through the osteotomy site seemed to be one of the reasons why the nonunion rate in the PSS group was lower than that in the DMCGS group. Nonunion of the greater trochanter after trochanteric osteotomy can lead to persistent abductor weakness pain and dislocation of the prosthesis [1, 2, 10, 13, 19, 20]. Bal et al. reported that cancellous bone in the trochanteric bed was frequently compromised as a result of osteolysis or from bone loss occurring during implant removal, and pressurised cement could extrude into the cancellous bony trabeculae, further compromising the available bone [3]. Therefore, even if the PSS is used, attention should be paid to the condition of the trochanteric bed and the tension of the abductor muscles after osteotomy of the greater trochanter in revision hip arthroplasty. On the other hand, the number of cable breaks in the PSS group was lower than that in the DMCGS group. This may be attributable to the fact that titanium was used as the material in the PSS, involving less risk of corrosion and that the use of smaller pins caused less irritation to the surrounding tissues.

Cable fragmentation was found in 20% of the DMCGS group and in only 4.8% of the PSS group in our series. The cable fragmentation in our cases was always around the grip, due to the fraying at the cut ends of the cables. Moreover, in 5.7% with fragmentations in the DMCGS group, the fragments had migrated close to the cup. Silverton et al. reported that although fraying of the cut cable ends is not a major complication, the consequence of loose metallic debris floating near the joint could give rise to increased polyethylene wear and potentially decrease the longevity of the arthroplasty [18]. Glover et al. reported that fractured trochanteric wire migration caused sciatica in two cases [8]. We therefore considered it necessary to cut the cable ends as short as possible so as not to leave the ends protruding from the sleeve. This was possible because of the special cutters in the PSS, designed to allow the cables to be cut off as close to the sleeve and as short as possible. On the other hand, in our series, bone absorption around the cable, grip, and sleeve was revealed in 54.3% in the DMCGS group, while it significantly decreased to 11.9% in the PSS group. There was no progressive osteolysis in two hips in our series with their migrating cable debris. Therefore, we believe that migrating cable debris should be followed carefully, and broken cable fragments after radiographic evidence of bone union should be removed as soon as possible.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective nature; consequently, the patient evaluations were subjective. A future prospective randomised study should also corroborate these findings. As it was also an observational series, there was no control group.

In conclusion, compared with the DMCGS, these clinical and radiological results suggest the PSS could be the instrument of choice for re-attachment of the greater trochanter in hip arthroplasty.

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: N.T. performed the clinical and radiological evaluation and analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Amstutz HC, Maki S. Complications of trochanteric osteotomy in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1978;60(A):214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amstutz HC, Mai LL, Schmidt I. Results of interlocking wire trochanteric reattachment and technique refinements to prevent complications following total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;183:82–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bal BS, Maurer BT, Harris WH. Trochanteric union following revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:29–33. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browne AO, Sheehan JM. Trochanteric osteotomy in Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;211:128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke RP, Jr, Shea WD, Bierbaum BE. Trochanteric osteotomy: analysis of pattern of wire fixation failure and complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:102–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dall DM, Miles AW. Reattachment of the greater trochanter. The use of the trochanter cable-grip system. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1983;65(B):55–59. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B1.6337168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel A, Booth RE, Jr, Balderston RA, Cohn J, Rothman RH. Complications of trochanteric osteotomy. Long-term implications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;288:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glover MG, Convery FR. Migration of fractured greater trochanteric osteotomy wire with resultant sciatica. A report of two cases. Orthopedics. 1989;12:743–744. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19890501-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottschalk FA, Morein G, Weber F. Effect of the position of the greater trochanter on the rate of union after trochanteric osteotomy for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3:235–240. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(88)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris WH, Crothers OD. Reattachment of the greater trochanter in total hip-replacement arthroplasty. A new technique. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1978;60:211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoman M, Sekiguchi M, Izumi T, Uchiyama K, Motobu J, Kuramoto K. Development of new tension wiring system (pin-sleeve system) Rinsho Seikei Geka (Clin Orthop Surg) 1999;34:735–744. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen NF, Harris WH. A system for trochanteric osteotomy and reattachment for total hip arthroplasty with a ninety-nine percent union rate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;208:174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kavanagh BF, Ilstrup DM, Fitzgerald RH., Jr Revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1985;67(A):517–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama K, Higuchi F, Kubo M, Okawa T, Inoue A. Reattachment of the greater trochanter using the Dall-Miles cable grip system in revision hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:22–27. doi: 10.1007/s007760170020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy JC, Bono JV, Turner RH, Kremchek T, Lee J. The outcome of trochanteric reattachment in revision total hip arthroplasty with a cable grip system: mean 6-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:810–814. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritter MA, Eizember LE, Keating EM, Faris PM. Trochanteric fixation by cable grip in hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1991;73(B):580–581. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schutzer SF, Harris WH. Trochanteric osteotomy for revision total hip arthroplasty. 97% union rate using a comprehensive approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;227:172–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverton CD, Jacobs JJ, Rosenberg AG, Kull L, Conley A, Galante JO. Complications of a cable grip system. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:400–404. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volz RG, Brown FW. The painful migrated ununited greater trochanter in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1977;59(A):1091–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo RY, Morrey BF. Dislocations after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1982;64(A):1295–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]