Abstract

Fifty-three patients with A2.2 and A2.3 intertrochanteric fracture according to the Muller classification were treated with total hip replacement between April 2000 and February 2004. The average age of the patients was 77 years. Average follow-up period was 3.7 years. We studied postoperative complications, mortality rate, functional outcome using the Harris hip score, time to return to normal activities, and radiographic evidence of healing. Two patients died on the third and fifth postoperative days. Seven more patients died within one year. The Harris hip score at one month was 66 ± 7 (mean ± standard deviation); at three months 72 ± 6; at one year 74 ± 5; at three years 76 ± 6 and in the 27 patients who completed five year follow-up it was 76 ± 8. Mobilisation and weight-bearing was started immediately in the postoperative period. Average time taken to return to normal daily activities was 28 days (range 24–33). No loosening or infection of the implants was observed. Total hip arthroplasty is a valid treatment option for mobile and mentally healthy elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures. This procedure offers quick recovery with little risk of mechanical failure, avoids the risks associated with internal fixation and enables the patient to maintain a good level of function immediately after surgery.

Introduction

Unstable intertrochanteric fractures in elderly patients are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Comminution, osteoporosis, and instability often preclude the early resumption of full weight bearing in spite of use of internal fixation [2]. Reported overall failure rate with internal fixation in intertrochanteric fractures has been reported to be 3–16.5% [3, 4]. In the elderly, fracture instability, comminution and osteoporosis worsens the prognosis [4, 5]. Moreover, there is a high rate of general complications associated with internal fixation due to prolonged recovery time taken after surgery [6, 7].

Various authors have reported successful outcomes after use of hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty in these patients [8–15]. After hip arthroplasty, patients can bear weight immediately, they can be encouraged to walk early and exercise the involved limb, thus reducing the period of bed rest and rate of complications [11, 12]. Our study was made with the purpose of presenting the clinical and roentgenographic results that were obtained with total hip arthroplasty as a primary treatment for intertrochanteric fractures in elderly patients and to review the results reported in the literature.

Patients and methods

In a retrospective study, between January 2000 and February 2005, a total of 69 consecutive patients of age greater than 70 years (average 77 years) having unstable intertrochanteric fractures (Muller A2.2 and A2.3) were treated by primary total hip replacement. Sixteen patients were lost in follow-up and were excluded from the study making the number of patients in the study 53. The follow-up period ranged from three to five years. There were 39 males and 14 females. Twenty-four cases injured the right side and 29 the left. All patients were given perioperative enoxaparin and support stockings as deep vein thromboprophylaxis.

Surgical technique All patients were treated within 48 hours of admission. Patients were operated upon under spinal or general anaesthesia by the same team of surgeons. They were prepared for surgery as for routine total hip replacement and positioned in a lateral position on the table. One assistant held the limb in traction to avoid further displacement of the fragments. We used the posterolateral approach to the hip in all cases. After splitting the fibres of the gluteus maximus the gluteus medius was retracted to expose the short external rotator muscles of the hip. These were divided close to their insertion and an inverted T shaped incision was made on the joint capsule. Fragments of the greater trochanter were fixed with the help of stainless steel wire. The femoral neck was osteotomised and the femoral head was removed. The acetabulum was prepared and a cemented acetabular cup (Charnley, LPW, 22 mm; Ormed, Germany) was implanted. The femur was positioned by internal rotation and adduction. After careful detection, the femoral canal was prepared by graduated reaming using rasps. The femoral component (Charnley, 316 L stainless steel; Ormed, Germany) was inserted and positioned inside the femoral canal using a manual cementing technique. Fixation of the greater trochanter was reinforced with cement wherever required. Isolated displaced fragments of the lesser trochanter were not reduced. Range of motion and stability were checked after reduction. The capsule was repaired followed by reattachment of the short external rotators to the femur. All wound closures were carried out over the closed suction drain.

Postoperative follow-up Postoperatively the limb was kept in abduction by using an abduction wedge. Haemoglobin level and packed cell volume were assessed after 12 hours of surgery. Blood transfusions were given wherever required. Drains were removed after 48 hours and check films were done. The breathing exercises and static exercises for calves, quadriceps and gluteal muscles were taught from the first day. Patients were allowed to sit and stand out of bed twice daily from the second postoperative day and range of motion exercises were begun. All patients were instructed to avoid excessive flexion and adduction. A pillow was kept between the thighs during the night for the first three weeks to prevent excessive adduction. An abduction brace was used during the daytime. Gait training with the help of a walker was started from the third postoperative day. The patient was discharged after complete rehabilitation. Average duration of stay in the hospital was 9.5 days (range, 7–13). Further care was continued in the rehabilitation department until the patient was independent enough for self care. Patients were followed at monthly intervals for three months, then every three months for a year, and yearly thereafter. The patients were clinically and radiologically evaluated at each visit and Harris hip scores were calculated.

Results

The mean operative time was 110 minutes (range, 60–165). Average intraoperative blood loss was 295 ml (range, 150–500) and the average postoperative drainage was 160 ml (range, 40–290). On an average, two units of supplemental transfused blood were required per patient.

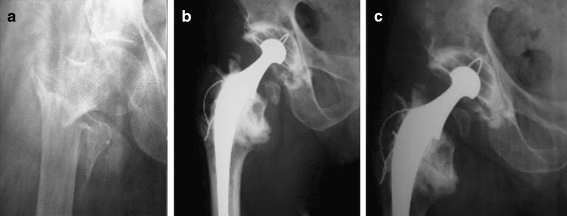

Follow-up period ranged from three to five years with a mean duration of 3.7 years. Two patients, who were known cases of ischaemic heart disease, died on the third and fifth days postoperatively following myocardial infarction. One patient died within the first three months of surgery following a road traffic accident. Another six patients died of causes unrelated to the fracture making a total of nine patients who died within the first year of surgery. The Harris hip score at one month was 66 ± 7, at three months it was 72 ± 6, at one year 74 ± 5, and at the three-year follow-up it was 76 ± 6. In 27 patients who had completed five years of follow-up, the score was 76 ± 8. Patients returned to their normal daily activities after 28 days (range, 24–33). Average time taken by fractures to heal was 3.6 months. All fractures demonstrated good radiological healing at the time of the last available follow-up (Fig. 1). Ten patients showed nonunion of the lesser trochanter. Limb lengthening of 0.5–1.0 cm was noticed in 13 patients.

Fig. 1.

Intertrochanteric fracture in a 78-year-old man treated with total hip arthroplasty. a Preoperative. b Six months postoperative. c Five years postoperative

None of the patients showed implant loosening, femoral subsidence or infection up to the last follow-up. Two patients had dislocation of the affected hip after four months and six months of surgery. Both were caused by significant trauma and were managed by closed reduction.

Discussion

The incidence of all hip fractures is approximately 80 per 100,000 persons and is expected to double over the next 50 years as the population ages [16]. Intertrochanteric fractures make up 45% of all hip fractures [17]. Many of these fractures are stable two-part fractures that can be treated satisfactorily with a sliding hip screw. But 35–40% are unstable three and four part fractures that are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality [17]. The reported overall failure rate with internal fixation in intertrochanteric fractures is 3–16.5% [3, 4]. The rate is higher in unstable fractures.

There is a considerable incidence of complications such as pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis and pneumonia when these fractures are treated by internal fixation. The complications are related to restricted weight-bearing and prolonged bed rest. In elderly patients, instability of the fractures and osteoporosis result in poor fixation that cannot tolerate immediate weight bearing [11]. Mortality rate in hospital ranges from 0.03 to 10.5%, while one year mortality reaches 22% [18].

Due to high failure rate and complications associated with internal fixation, many authors have used hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty as primary treatment of these fractures. Tronzo reported the use of a long straight-stem prosthesis for intertrochanteric fractures in 1974 [9]. In 1979, Stern and Goldstein reported 43 cases of comminuted intertrochanteric fractures treated by long-stem Leinbach prostheses [10]. Later, many authors suggested the use of hip replacement to treat comminuted intertrochanteric fractures, emphasising the rapid weight-bearing allowed from the first postoperative day and faster return of the patients to a prefracture ambulatory state [11–14]. Elderly patients, who are often unable to cooperate with partial weight-bearing required after an internal fixation, accept full weight-bearing easily. This reduces the period of bed rest and rate of complications [11, 12].

Haentjens et al., in two different studies, concluded that arthroplasty gives better results than internal fixation in unstable intertrochanteric fractures in elderly osteoporotic patients [11, 12]. The author noted that arthroplasty permits rapid recovery with immediate weight-bearing, and maintenance of a good level of function with little risk of mechanical failure.

In a recent study, Faldini et al. reported use of hemiarthroplasty and total hip replacement in 54 patients [8]. They concluded that hip replacement permits a more rapid recovery with immediate weight-bearing and facilitates nursing care better than other fixation techniques.

We performed total hip replacement in all our patients. There is to date no study available that compares the outcomes of bipolar hemiarthroplasty and THR in intertrochanteric fractures. But the data from neck of femur fractures suggests that total hip arthroplasty is a better implant than hemiarthroplasty [19]. Acetabular erosion is the major risk associated with hemiarthroplasty [20, 21]. Compromised articular cartilage in the hips of normal elderly patients puts them at a greater risk [22]. Repeated articulations may lead to lesions in acetabular cartilage severe enough to limit the activity resulting in higher revision surgery [20, 23]. Total hip arthroplasty demonstrates superior longevity when compared to hemiarthroplasty [23, 24].

Dislocation is the major concern after total hip arthroplasty [11]. In patients with intertrochanteric fracture undergoing total hip arthroplasty, the reported rate of dislocation is 0–44.5% [11]. Postoperative dislocations are associated with higher rate of pulmonary complications and bed sores [25]. We took utmost periperative and postoperative precautions to minimise the risk of dislocation. This included optimal orientation of the acetabular component, use of an acetabular component with a long posterior wall, and repair of the capsule. Postoperatively we used an abduction brace for three weeks, physiotherapy and supervision in activities of daily living. None of our patients had dislocation in the immediate postoperative period. Dislocation was seen in two patients at four and six months after surgery. Both of them were caused by significant trauma and were managed by closed reduction and rest.

In our study, total hip arthroplasty was associated with better functional outcomes than those reported with the use of internal fixation. One year mortality in our study was 17%. This mortality rate is comparable to what other authors have reported with the use of internal fixation or replacement [6, 8]. Patients were able to perform their normal activities within a month and they showed progressive improvement in the first three months. All patients demonstrated good functional achievement in spite of their advanced age.

We think that prefracture activity of the patient should be taken into consideration when making a decision for surgery. Though we did not make an objective assessment of prefracture mobility and activity, all our patients were community ambulators before injury and were not dependent for self care. Such patients are expected to lead an active life after treatment and total hip replacement is a better option than hemiarthroplasty.

In conclusion we state that total hip arthroplasty is a valid treatment option for mobile and mentally healthy patients. This procedure offers quick recovery with little risk of mechanical failure, avoids the risks associated with internal fixation and enables the patient to maintain a good level of function beginning in the immediate postoperative period.

References

- 1.White BL, Fisher WD, Laurin CA. Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of the hip in the 1980’s. J Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69-A:1335–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Said GS, Farouk O, El-Sayed A, Said HG. Salvage of failed dynamic hip screw fixation of intertrochanteric fractures. Injury. 2006;37:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haentjens P, Casteleyn PP, Opedecam P. Hip arthroplasty for failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in the elderly patient. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1994;113(4):222–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00441837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis TR, Sher JL, Horsman A, Simpson M, Porter BB, Checketts RG. Intertrochanteric femoral fractures. Mechanical failure after internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:26–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B1.2298790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim WY, Han CH, Park JI, Kim JY. Failure of intertrochanteric fracture fixation with a dynamic hip screw in relation to pre-operative fracture stability and osteoporosis. Int Orthop. 2001;25(6):360–362. doi: 10.1007/s002640100287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM. Intramedullary versus extramedullary fixation for the treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures. Clin Orthop. 1998;348:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brostrom LA, Barrios C, Kronberg M, Stark A, Walheim G. Clinical features and walking ability in the early postoperative period after treatment of trochanteric hip fractures. Results with special reference to fracture type and surgical treatment. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1992;81:66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faldini C, Grandi G, Romagnoli M, Pagkrati S, Digennaro V, Faldini O, Giannini S. Surgical treatment of unstable intertrochanteric fractures by bipolar hip replacement or total hip replacement in elderly osteoporotic patients. J Orthop Traumatol. 2006;7(3):117–121. doi: 10.1007/s10195-006-0133-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tronzo RG. The use of an endoprosthesis for severely comminuted trochanteric fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 1974;5(4):679–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern MB, Goldstein T. Primary treatment of comminuted intertrochanteric fractures of the hip with a Leinbach prosthesis. Int Orthop. 1979;3(1):67–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00266327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haentjens P, Casteleyn PP, Boeck H, Handleberg F, Opedcam P. Treatment of unstable intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in elderly patients. Primary bipolar arthroplasty compared with internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1214–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haentjens P, Casteleyn PP, Opdecam P. Primary bipolar arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of unstable intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in elderly patients. Acta Orthop Belg. 1989;60(Suppl 1):124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahl AC, Jacobs PBD, Patka P, Haarman Hemiarthroplasty in elderly, debilitated patients with an unstable femoral fracture in the trochanteric region. Acta Orthopedica Belgica. 1994;60:274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodop O, Kiral A, Kaplan H, Akmaz I. Primary bipolar hemiprosthesis for unstable intertrochanteric fractures. Int Orthop. 2002;26:233–237. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0358-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern MB, Angerman A. Comminuted intertrochanteric fractures treated with a Leinbach prosthesis. Clin Orthop. 1987;218:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuckerman JD. Hip fractures. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1519–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimsrud C, Monzon RJ, Richman J, Ries MD. Cemented hip arthroplasty with a novel circlage technique for unstable intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aprin H, Kilfoyle RM. Treatment of trochanteric fractures with Ender rods. J Trauma. 1980;20(1):32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keating JF, Grant A, Masson A, Scott NW, Forbes JF. Randomised comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty and total hip replacement: treatment of displaced intracapsular hip fracture in healthy older patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:149–260. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalldorf PG, Banas MP, Hicks DG, Pellegrini VD. Rate of degeneration of human acetabular cartilage after hemiarthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:877–882. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takaoka K, Nishina T, Ohzono K, Saito M, Matsui M, Sugano N, et al. Bipolar prosthetic replacement for the treatment of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop. 1992;277:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lester DK, Wertenbruch JM, Piatkowski AM. Degenerative changes in normal femoral heads in the elderly. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:200–203. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur-13 year results of a prospective randomized study. Injury. 2000;31(10):793–797. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebhard JS, Amstutz HC, Zinar DM, Dorey FJ. A comparison of total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty for treatment of acute fracture of the femoral neck. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;282:123–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haentjens P, Lamraski G. Endoprosthetic replacement of unstable, comminuted intertrochanteric fracture of the femur in the elderly, osteoporotic patient. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(18–19):1167–1180. doi: 10.1080/09638280500055966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]