Abstract

While options for operative treatment of leg axis varus malalignment in patients with medial gonarthrosis include several established procedures, such as unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or high tibial osteotomy (HTO), there has been little focus on a less invasive option introduced more recently: the UniSpacer™ implant, a self-centering, metallic interpositional device for the knee. This study evaluates clinical and radiological results of the UniSpacer™, whether alignment correction can be achieved by UniSpacer™ arthroplasty and alignment change in the first five postoperative years. Anteroposterior long leg stance radiographs of 20 legs were digitally analysed to assess alignment change: two relevant angles and the deviation of the mechanical axis of the leg were analysed before and after surgery. Additionally, the change of the postoperative alignment was determined one and five years postoperatively. Analysing the mechanical tibiofemoral angle, a significant leg axis correction was achieved, with a mean valgus change of 4.7 ± 1.9°; a varus change occurred in the first postoperative year, while there was no significant further change of alignment seen five years after surgery. The UniSpacer™ corrects malalignment in patients with medial gonarthrosis; however, a likely postoperative change in alignment due to implant adaptation to the joint must be considered before implantation. Our results show that good clinical and functional results can be achieved after UniSpacer™ arthroplasty. However, four of 19 knees had to be revised to a TKA or UKA due to persistent pain, which is an unacceptably high revision rate when looking at the alternative treatment options of medial osteoarthritis of the knee.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the medial compartment of the knee is associated with varus malalignment [4, 6]. In the operative treatment of gonarthrosis affecting solely the medial compartment, the most commonly used options, especially in younger patients, are high tibial osteotomy (HTO) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA). Both procedures require resection of bone material; the latter also requires knee joint surgery [13].

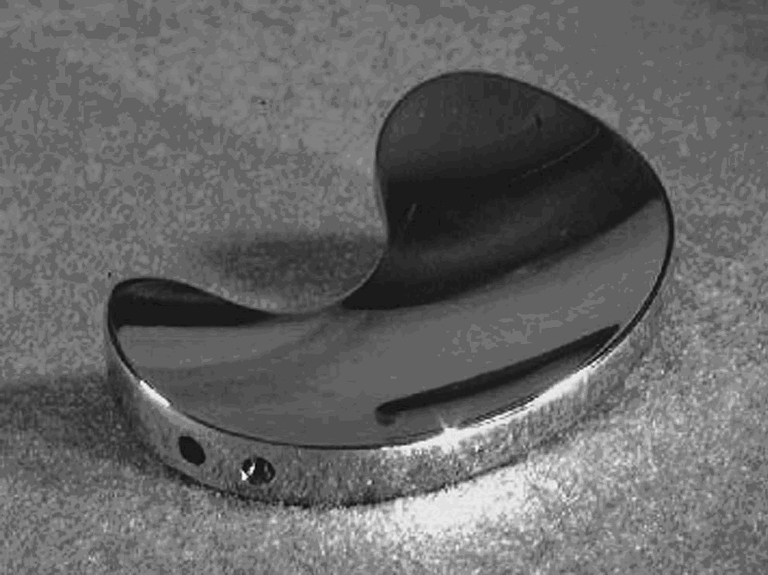

A less invasive alternative to these well-established procedures has been available in recent years: the UniSpacer™ implant (Zimmer, Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA), which is essentially a modern version of early metallic hemiarthroplasty as described by McKeever [17] or MacIntosh [16]. However, a rate of failure between 16 and 44% has been described in the literature [1, 23].

Implantation of this self-centering, one-piece interpositional device into the knee joint does not require any resection of bone stock and is performed via minimally invasive surgery. It is available in several thicknesses and adapts to knee kinematics [21]. In contrast to the recently introduced ConforMIS iForma™ knee implant [15], the UniSpacer™ is a self-centering device that is not fixed to any structures (“self-centering”); it is used to correct or minimise varus malalignment in unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee where other procedures are not indicated (Fig. 1). The upper surface of the implant postoperatively adapts to the femoral condyle [21].

Fig. 1.

UniSpacer™ metallic interpositional device

The UniSpacer™ is indicated in patients with isolated moderate degeneration of the medial compartment with minimal degeneration and no loss of joint space in the patellofemoral compartment. Absolute contraindications are inflammatory arthritis, severe instability due to advanced loss of osteochondral structure or the absence of collateral/cruciate ligament integrity or flexion contracture greater than 15°.

The notion of a self-centering mobile component correcting the varus knee internally without any need for bone resection has been, and still is, appealing. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate clinical and radiological results, whether appropriate alignment change can be achieved by UniSpacer™ implantation and whether this change correlates with the thickness of the implant used. Also, alignment change in the first five years after surgery is examined.

Materials and methods

In a retrospective study, 18 patients (19 legs) presenting with moderate stage isolated medial gonarthrosis, who had received UniSpacer™ hemiarthroplasty between 2002 and 2004, were assessed (implant thickness: 2, 3 or 4 mm). One patient received bilateral implantation; 12 right and seven left knees had been treated. The average age of the patients (seven women and 11 men) at the time of surgery was 60.8 (48–72) years.

Anteroposterior long leg stance radiographs, taken preoperatively and three weeks, one and five years after surgery using a standardised technique [18], were digitally analysed to assess alignment change. A standard protocol was followed by ensuring that hip, knee and metatarsal joints were included while the patient was standing upright and the patellae were frontally aligned.

The digitised radiographs were evaluated using mediCAD® (Hectec GmbH, Niederviehbach, Germany), a surgical planning software which can also be used for biometric purposes. The mechanical tibiofemoral angle (mTFA) (i.e. the angle of the mechanical axes of the femur and tibia) was measured. The anatomical tibiofemoral angle (aTFA) (i.e. the angle between the anatomical axes of the two bones) was also measured. Additionally, we determined the location of the mechanical axis of the leg, or load-bearing axis, with respect to the centre of the tibial plateau, as described by Kennedy and White [14]: zones 1 and 2 are on the medial side, zones 3 and 4 are on the lateral side of the tibial eminence while zone C constitutes the central part of the tibial plateau.

According to convention, varus angles were designated as negative while valgus angles were designated as positive [4]. To assess the alignment change achieved by surgery, the difference between pre- and postoperative values of each angle was determined by subtraction. This was done using the respective postoperative values, to evaluate change in the first postoperative year and in the following four years.

For descriptive statistics, the mean value, standard deviation and median of the measured angles and the differences were determined. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the significance of alignment change.

The correlation between alignment correction and respective implant thickness was calculated using the Pearson product-moment correlation. To determine the significance of the calculated correlation, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used.

Results

The clinical scores [Lysholm, American Knee Society (AKS) knee and function] preoperatively and at one, two and five year follow-ups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical scores preoperatively and at 1-, 2- and 5-year follow-ups

| Clinical scores | Preoperative | 1 year postop. | 2 years postop. | 5 years postop. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysholm | 59.1 | 85.4 | 90.2 | 97.2 |

| AKS knee | 60.1 | 87.4 | 88.7 | 96.6 |

| AKS function | 70.0 | 93.8 | 98.5 | 96.4 |

Leg axis was corrected from a preoperative average of −5.1 ± 3.0° to an average of −0.4 ± 2.3° after surgery (mTFA); this amounts to a mean correction of 4.7 ± 1.9° achieved by surgery (p = 0.001).

One year after surgery, mean mTFA was −1.5 ± 1.8°. Mean alignment change in the first year after surgery amounted to −1.1 ± 1.5° (varus!) (p = 0.023).

Five years after surgery, the average was −0.7 ± 1.6° (mTFA). The mean change of valgus was 0.9 ± 1.1° (p = 0.019).

Only 15 legs could be evaluated, as four patients had undergone revision UKA or TKA due to persistent pain. The average time to revision for the knees revised to TKA or UKA was 23.8 (± 18.0) months. So far, no dislocations have been observed in our study.

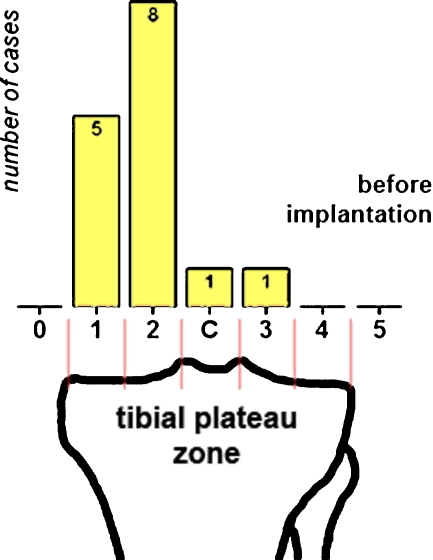

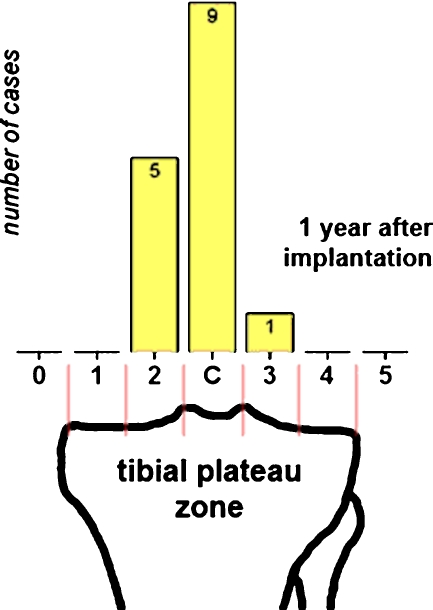

With regard to the location of the mechanical axis of the leg in relation to the tibial plateau, before surgery, zone 1 was represented in five cases, zone 2 in eight cases and zones C and 3 were represented in one case each (Fig. 2). After surgery, zone 2 was represented in four cases, zone C in nine cases and zone 3 in two cases (Fig. 3). This implies that the location of the load-bearing axis (in tibial plateau zones) was not changed by surgery in three cases, while in nine cases, there was a lateral shift by one zone; in three cases, there was a lateral shift by two zones. One year after surgery in nine legs no further change was found; in four cases, there had been a medial shift by one zone; in two cases, there had been a lateral shift by one zone (zone 2: five cases, zone C: nine cases, zone 3: one case, Fig. 3). At five years postoperatively, in two of those four cases, the axis had shifted back again into zone C so that at this time, there were only three legs with a load-bearing axis located in zone 2, while the majority (eight legs) it was in zone C.

Fig. 2.

Location of leg axis in relation to tibial plateau before UniSpacer™ surgery (number of cases per zone)

Fig. 3.

Location of leg axis in relation to tibial plateau 1 year after UniSpacer™ surgery (number of cases per zone)

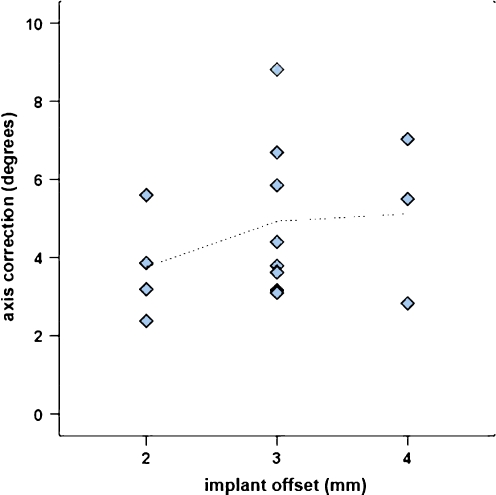

Correlation with implant thickness

The correlation coefficient r between the extent of alignment change (mTFA) and implant thickness calculated was 0.274 (Fig. 4). The accuracy with which the axis correction by UniSpacer™ surgery related to the thickness of the implant used was not significant (p = 0.162).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of axis correction and implant thickness

Discussion

The use of HTO in the treatment of symptomatic knees with varus malalignment has been promoted and thoroughly documented for several decades: it is a well-established therapeutic option [19]. UKA has recently experienced a renewal of interest, with improved prostheses and techniques used. There have been reports of good long-term results for these methods. However, both can lead to distinct issues that may trouble patients over the course of time. UKA comes with loss of bone matter in the medial compartment and, if conversion to TKA becomes necessary, bone grafts or metal wedge augmentation may be required in some cases [24]. HTO affects ligament tension and joint kinematics [9], which can lead to difficulties during revision TKA: complications arise more frequently in TKA following HTO than in primary TKA [25]. OA has been shown to progress more rapidly in the contralateral compartment after HTO [12]. On the other hand, after UKA, contralateral compartment OA progression occurs in a small number of cases only [7].

Hemiarthroplasty with metallic interpositional devices, while first described over half a century ago, is also currently experiencing a renaissance as a treatment option for varus unicompartmental OA, the idea being to provide a means of treatment that minimises the disadvantages of other procedures. It is used in cases where HTO is contraindicated or patients are too young for TKA. The current literature on hemiarthroplasty is rare. The ConforMIS iForma™ device, following the MacIntosh and McKeever rationale in being functionally fixed to the tibial surface, has had one favourable review in a recent article [15]; there are still few reports examining the use of the self-centering UniSpacer™ device in medial gonarthrosis. This study is the first to evaluate clinical and functional results after a minimum follow-up time of five years. Only one study addresses the matter of malalignment correction [10]. However, results were based on 40-cm instead of long-leg stance radiographs and therefore not reliable [3, 18]. Use of the UniSpacer™ in unicompartmental OA was initially recommended for young and active patients [10]. The role of this procedure still is uncertain as it has been considered suitable for only a few patients (1%) [22] and there have been reports of poor postoperative results due to implant dislocation (up to 44%) [1, 23].

With regard to the desired extent of correction, the aim of over-adjustment into valgus alignment has been voiced as desirable for HTO in varus medial gonarthrosis [5, 11]. The optimal extent achieved by UKA still is under discussion [7, 26] with an overall mechanical alignment of the knee through the tibial plateau centre (zone C) resulting in most cases, as described by Emerson and Higgins [8]. There are almost no data for interpositional hemiarthroplasty. The study by Koeck et al. on the iForma™ implant [15] showed an average postoperative alignment (mTFA) of −0.9° and a mean correction of 3.8°. A significant correlation between extent of correction and thickness of the implant was shown.

Cooke et al. described an average knee alignment (mTFA) of −1.0 ± 2.8° in the normal patient [2], while Moreland et al. found an average of −1.3 ± 2.0° to be normal [18]. According to these values, UniSpacer™ patients experienced a slight over-adjustment in our study.

We advocate the use of an approach for evaluation of knee geometry, as employed by Emerson and Higgins in their Oxford prosthesis study [8] (assessment of the load-bearing axis in relation to the tibial plateau), as swift and well standardised, being more easily demonstrable than the sole use of angles.

This study showed a significant, slightly over-adjusting correction of moderate varus alignment by UniSpacer™ arthroplasty, which does not correlate with the thickness of the implant used. In the first postoperative year, a varus shift into a more neutral position was observed, which is most likely due to adaptation of the implant to the joint. This effect is partly reversed in the following years by another slight valgus change, resulting, five years after surgery, in an average leg axis close to the one first achieved by UniSpacer™ implantation.

Our study showed a high revision rate of four of 19 UniSpacer™ implants in the first five postoperative years, which is unacceptably high. The reason for revision was persistent pain. We had no cases of dislocations. All revisions were technically easy and uncomplicated. In all cases either UKA (two) or TKA (two) was performed and the patients were satisfied with the clinical results achieved after revision.

In view of the high revision rates of the UniSpacer™ implant reported in the literature and in our study, this metallic interposition arthroplasty does not seem to be a treatment option for patients with medial osteoarthritis of the knee. As there are reproducible good and excellent clinical and functional results reported with UKA after ten to 15 years, this operation should be preferred [20]. However, the clinical results of our remaining 14 patients with 15 treated knees were good and comparable to patients after UKA. Similar to the results of the metallic interpositional device of McKeever, good results can be possible; however, the results are not predictable [21].

Conclusions

As a minimally invasive procedure, UniSpacer™ arthroplasty was seen as an alternative for treatment of varus malaligned knees in isolated medial gonarthrosis, due to good revision and conversion options. Judging from medium-term results, a slight over-adjustment with a target range of around 0.5° varus to 0.0°, accounting for postoperative implant-joint adaptation, seems reasonable.

However, as reported in other studies, there is an unacceptable rate of failures, resulting from pain. Since there is little literature on the topic, there should be greater focus on this treatment option in further studies, especially in view of new, similar interpositional alternatives, which are fixed inside the joint rather than self-centering.

References

- 1.Bailie AG, Lewis PL, Brumby SA, et al. The Unispacer knee implant: early clinical results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):446–450. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooke TD, Li J, Scudamore RA. Radiographic assessment of bony contributions to knee deformity. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(3):387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooke TD, Scudamore RA, Bryant JT, et al. A quantitative approach to radiography of the lower limb. Principles and applications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(5):715–720. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B5.1894656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooke TD, Scudamore RA, Li J, et al. Axial lower-limb alignment: comparison of knee geometry in normal volunteers and osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1997;5(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/S1063-4584(97)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coventry MB, Ilstrup DM, Wallrichs SL. Proximal tibial osteotomy. A critical long-term study of eighty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(2):196–201. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derek T, Cooke V, Scudamore RA, et al. Axial alignment of the lower limb and its association with disorders of the knee. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2000;8(2):98–107. doi: 10.1053/otsm.2000.6575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshmukh RV, Scott RD. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:272–278. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emerson RH, Jr, Higgins LL. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with the oxford prosthesis in patients with medial compartment arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):118–122. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaasbeek RD, Nicolaas L, Rijnberg WJ, et al. Correction accuracy and collateral laxity in open versus closed wedge high tibial osteotomy. A one-year randomised controlled study. Int Orthop. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0861-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallock RH, Fell BM. Unicompartmental tibial hemiarthroplasty: early results of the UniSpacer knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;416:154–163. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093031.56370.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernigou P, Medevielle D, Debeyre J, et al. Proximal tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis with varus deformity. A ten to thirteen-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(3):332–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Insall JN, Joseph DM, Msika C. High tibial osteotomy for varus gonarthrosis. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(7):1040–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iorio R, Healy WL. Unicompartmental arthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(7):1351–1364. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200307000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy WR, White RP. Unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. Postoperative alignment and its influence on overall results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;221:278–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koeck F, Perlick L, Luring C, et al. Leg axis correction with ConforMIS iForma (interpositional device) in unicompartmental arthritis of the knee. Int Orthop. 2009;33(4):955–960. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0577-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacIntosh DL. Hemiarthroplasty of the knee using a space occupying prosthesis for painful varus and valgus deformities. In: Proceedings of the Joint Meeting of the Orthopaedic Associations of the English-Speaking World. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40(6):1428–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeever DC. Tibial plateau prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1960;18:86–95. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000187336.17627.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreland JR, Bassett LW, Hanker GJ. Radiographic analysis of the axial alignment of the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(5):745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelissen EM, Langelaan EJ, Nelissen RG. Stability of medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy: a failure analysis. Int Orthop. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0723-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price AJ, Waite JC, Svard U. Long-term clinical results of the medial Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:171–180. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200506000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott RD. UniSpacer: insufficient data to support its widespread use. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;416:164–166. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093027.56370.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott RD, Deshmukh RV. Metallic hemiarthroplasty of the knee. Curr Opin Orthop. 2005;16(1):35–37. doi: 10.1097/01.bco.0000152814.36045.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisto DJ, Mitchell IL. UniSpacer arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1706–1711. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Springer BD, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:214–220. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000214431.19033.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tunggal JA, Higgins GA, Waddell JP (2009) Complications of closing wedge high tibial osteotomy. Int Orthop. doi:10.1007/s00264-009-0819-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Whiteside LA. Making your next unicompartmental knee arthroplasty last: three keys to success. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(4 Suppl 2):2–3. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]