Abstract

The aim of the study was to evaluate the reliability and durability of alumina-on-alumina ceramic in comparison to metal-on-highly cross-linked polyethylene (CoCr/HXLPE) bearing couples. This prospective randomised study involved 150 patients (157 hips). All patients (mean age: 54.7 years) obtained an identical fibre metal midcoat femoral stem and fibre metal-coated acetabular shell. In 78 patients (82 hips) we used alumina, while in 72 patients (75 hips) metal-polyethylene bearing couples were used. During a mean 50.4-month follow-up period (51 ± 8 alumina and 50 ± 8.9 metal-polyethylene) no statistically significant changes in clinical and radiographic parameters were noted between the two groups. There was no ceramic breakage and no need for revision surgery due to the ceramic liner. The alumina bearing couples proved to be as reliable as CoCr/HXLPE.

Introduction

For over six decades the artificial hip has represented the best solution for painful degenerative hip conditions. Today, orthopaedic surgeons have at their disposal a variety of endoprosthetic systems with different bearing surfaces. The current task of endoprosthetic systems is to achieve a longer lifespan than the previous ones. The greatest challenge today is to prolong their durability in young and active patients [9].

The goal of our research was to evaluate the reliability and endurance of the new alumina ceramic system. We postulated that the new alumina could be identically reliable and endurable as the metal-on-highly cross-linked polyethylene (CoCr/HXLPE) system.

Materials and methods

The subjects of this study were patients in whom we implanted total hip cementless endoprostheses of identical type: Zimmer stem VerSys porous collared, fibre metal midcoat; acetabular ring Trilogy, fibre metal-coated; with different bearing surfaces: alumina/alumina and CoCr/HXLPE. The external geometry of the metal components was identical regardless of the bearing couple (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cluster-hole press fit shell, fibre metal-coated, alumina ceramic acetabular insert, alumina ceramic femoral head and porous collared stem, fibre metal midcoat (left). Multi-hole press fit shell, fibre metal-coated, cross-linked polyethylene acetabular insert, cobalt-chrome femoral head and porous collared stem, fibre metal midcoat (right)

The study was conducted at the Institute of Orthopaedic Surgery “Banjica” Belgrade from January 2003 to April 2008, designed as a prospective randomised study. The minimal sample size necessary to secure the probability of at least 70% so as to detect the incidence difference of 6% of postoperative complications, at the level of statistical significance of 0.05, was 131. Patients were randomly allocated using a table of random numbers. Other relevant variables of the study were: gender, age, body mass index (BMI), follow-up time and diagnosis.

The study included 150 patients; seven underwent a bilateral arthroplasty, so that the total number of artificial joints was 157. Of these, there were 82 alumina and 75 CoCr/HXLPE implants.

The inclusion criteria were: hip osteoarthritis (OA), age under 65 and high activity level—our intention was to test durability and reliability of the new alumina ceramic system in young and active patients. The exclusion criteria were: history of hip infection or degenerative damage of the joint due to infection.

The study group was composed of alumina and the control group of CoCr/HXLPE implants. All alumina femoral heads were 28 mm in diameter, while metal heads in seven cases were 32 mm in size if the acetabular ring was over 58 mm and in one case of bilateral arthroplasty when the first operation was complicated by dislocation.

Demographic data are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences between the groups. They were similar regarding gender, but in total the number of women was statistically significantly higher (75%, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and diagnosis

| Alumina/alumina | CoCr/HXLPE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients/hips (n) | 78/82 | 72/75 | |

| Male/female (%) | 21/79 | 31/69 | 0.21 |

| Right/left (%) | 42/58 | 44/56 | 0.07 |

| Age (years) | 53.9 ± 7.1 | 55.6 ± 6.5 | 0.13 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 3.8 | 27.8 ± 4.2 | 0.09 |

| Follow-up (months) | 51 ± 8.0 | 50 ± 8.9 | 0.46 |

| Diagnosis (%) | |||

| Primary osteoarthritis | 56 | 57 | >0.99 |

| Secondary osteoarthritis | |||

| Hip dysplasia | 35 | 20 | 0.07 |

| Avascular necrosis | 5 | 5 | 0.82 |

| Post-traumatic arthritis | 2 | 11 | 0.049* |

| Other | 2 | 7 | 0.26 |

CoCr cobalt chrome, HXLPE highly cross-linked polyethylene, BMI body mass index

*Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Based on these data, it could be concluded that the typical patient in the study was the young woman with hip OA.

Patient follow-up ranged from 34 to 63 months with a mean of 50.4 months.

The relevant clinical and radiographic data were collected preoperatively, six to eight weeks after surgery, six months after surgery and after that once a year. The radiographs were assessed by the surgeons. The main parameters were [4, 7]:

Clinical hip evaluation using the Harris Hip Score (HHS) [12]

Radiographic evaluation: presence of radiolucent line (RLL) in the standard zones, stability, migration, cortical erosion and osteolysis [8, 10, 11]

Complications: fractures of bone and/or implant, dislocations, infections, thromboembolism, heterotopic ossification and pedestal formation

In the analysis of primary data we used descriptive statistical methods (measures of central tendency, variability measures and relative numbers), methods for the study of relationship and methods in the testing of statistical hypotheses (χ2 and t test, with a significance level of 0.05).

Results

Clinical results

The mean postoperative HHS was 95.1 and 93.8 in the study and control groups, respectively. Painless or slightly painful hips were seen in 93% in the study group and in 95% in the control group. No limp or slight limping in the study and control groups were present in 98% and 96%, respectively, and the percentage of HHS rated as good and excellent was 95% in both groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and radiographic findings

| Alumina/alumina | CoCr/HXLPE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HHS | |||

| Preoperative (/100) | 45.6 ± 8.2 | 43.1 ± 8.2 | 0.06 |

| Postoperative (/100) | 95.1 ± 3.9 | 93.8 ± 5.1 | 0.07 |

| Pain none or slight (%) | 93 | 95 | 0.75 |

| Limp none or mild (%) | 98 | 96 | 0.67 |

| Patients’ satisfaction (%) | 98 | 97 | 1.00 |

| Good and excellent (%) | 96 | 94 | 0.48 |

| Radiographic findings | |||

| Femoral component | |||

| RLL zone 1 (%) | 1 | 7 | 0.08 |

| RLL zone 7 (%) | 1 | 4 | 0.27 |

| Subsidence | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Instability | 0 | 1 | 0.29 |

| Pedestal | 18 | 23 | 0.63 |

| Acetabular component | |||

| RLL zone 1 (%) | 2 | 3 | 0.93 |

| RLL zone 2 (%) | 1 | 0 | 0.34 |

| RLL zone 3 (%) | 1 | 3 | 0.51 |

| Migration | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

CoCr cobalt chrome, HXLPE highly cross-linked polyethylene, RLL radiolucent line

Radiographic results

The subcortical RLL, as a characteristic of subcortical erosions in femoral zones 1 and 7, was detected in the alumina bearing couples group in 1% of cases, respectively, while in the CoCr/HXLPE couples group it was seen in 7% and 4% of cases, respectively (there was no statistically significant difference between them; p = 0.075 and p = 0.27, respectively).

In the CoCr/HXLPE group, stem instability with varus progression occurred in one case (1%), in the first year of follow-up, and was treated by a revision.

The formation of a bone intraosseous bridge around or below the stem top (pedestal) was noted in the alumina group in 18% and in CoCr/HXLPE group in 23% of cases (total 20%). The pedestals were detected in a total of 32 cases; of these, 28 (86%) showed the characteristics of a stable stem, while the patients were asymptomatic.

In the acetabular zone 1, the RLL was noted in a total of four cases, two in each system tested. In zone 2, the RLL was detected in one implant with the ceramic insert. In zone 3 the RLL was noted in three implants: one in the study group and two in the control group (Table 2).

Complications

Complications are shown in Table 3. Two revision procedures were performed in total (1%), both in the control group.

Table 3.

Complications

| Total | Alumina/alumina | CoCr/HXLPE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revisions, n (%) | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 2 (2.6) | 0.23 |

| Cup | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Stem | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0.47 |

| Liner and/or head only | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0.47 |

| Ceramic fracture | - | 0 | - | - |

| Dislocation | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.6) | 0.61 |

| Ceramic liner chip | - | 3 (3.6) | - | - |

| Intraop. femoral crack | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0.34 |

| Deep joint infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Heterotopic bone | 6 (3.8) | 3 (3.6) | 3 (4.0) | 0.91 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0.29 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

CoCr cobalt chrome, HXLPE highly cross-linked polyethylene

Chipping of the alumina acetabular liner occurred during insertion in three cases; two were immediately replaced by new ones, and the third remained in the ring without secondary complications (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative ceramic insert chip. Damage of the ceramic insert edge occurred during impaction due to insufficiently precise placement in the acetabular shell

In the alumina group no revision was done. Also, there was no need for a revision of the acetabular components in any of the implant groups.

We encountered three dislocations (2%): one in the study group and two in the control group. In two cases the dislocation occurred due to a fall: in one male patient with an alumina bearing couple in the eighth postoperative month and in one female patient with a CoCr/HXLPE system six weeks after surgery. A month after reposition of the endoprosthesis, the latter patient developed signs of deep venous thrombosis, which was treated by low molecular weight heparin. In the third case hip dislocation occurred twice: four weeks after surgery and a few days after closed reduction.

Intraoperative femoral fracture occurred in a case from the study group. Deep infection or pulmonary embolism did not develop in any of the cases. Heterotopic ossifications were encountered in 4% of cases from each group, respectively. The earliest incidence of ossification was noted in the second year of follow-up.

Discussion

The artificial hip today is expected, in addition to ensuring painlessness, stability and durability, to enable all life activities, even those involving sport. With the new possibilities available, the indications for implantation of artificial joints have been also extended to young and active patients.

However, their durability is considerably decreased by debris occurring due to material wear which is the cause of osteolysis, resultant loosening and implant failure [1, 2, 4, 16, 18, 19].

The alumina bearing couples have numerous theoretical advantages. First is their resistance to rough mechanical damage and wear owing to the extreme hardness of ceramics. The degree of ceramic couples wear is below 1 μm/year, as compared to 200 μm/year of conventional metal-polyethylene [21]. Isostatic thermal press fit of the third-generation ceramic has made it highly resistant to breakage. Besides, alumina is a biocompatible material which does not release metal ions.

Ceramic breakage remains one of the factors that should be a future matter of concern. There is also the impingement of the femoral component neck and acetabular liner causing stem wear and the release of metal debris into the joint space, edge fractures of the acetabular liner and the occurrence of debris, which can finally lead to loosening [5]. Early ceramics of insufficient purity, low density and large size grain microstructure did not exhibit a sufficiently high mechanical resistance [24]. In the 1980s the inadequate design of ceramic components resulted in the unacceptable rate of fractures. In 1995 Callaway et al. reported that in the USA the frequency of alumina ceramic femoral head fractures was as high as 1.9% [3]. Nevertheless, the cause was not the poor material quality, but in the poor conus geometry at the junction between the metal stem of the neck and ceramic head. With the development of the Morse cone and the very precise production of metal and ceramic bearing surfaces of both implant components, the risk of stress and fracture was reduced to a minimum. None of the ceramic heads or acetabular liners broke in our study or in other reports available from the literature [4, 7].

In the demographic data analysis, a statistically significant difference occurred only in gender. Namely, there were more women, while the patients from the control group were slightly older. It is not surprising that there were a considerably greater number of women with hip arthroplasty. The reasons could probably be found in the fact that in our country women suffer from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) considerably more often, resulting in hip arthritis at a young age [13, 22]. Such an explanation is additionally supported by the data that the incidence of left hip arthroplasty in our study is higher, indicating the increased incidence of left hip disease (57%) (Figs. 3 and 4). Namely, it is known that in the cases of unilateral DDH the left hip is more often involved [23].

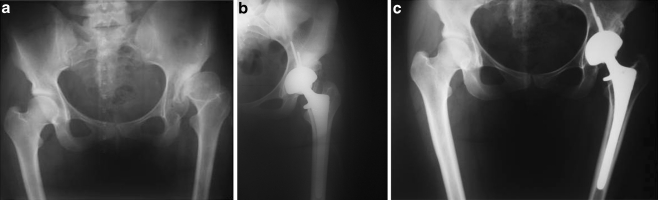

Fig. 3.

a Secondary degenerative disease of the left hip due to DDH in a 21-year-old woman, preoperative anteroposterior (AP) view. b The same patient, immediately after total hip arthroplasty (THA) with alumina bearing couple, AP view. c The same patient, 4 years postoperatively, AP view

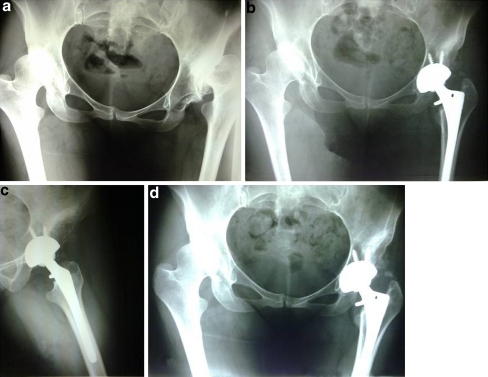

Fig. 4.

a Secondary degenerative disease of both hips due to DDH in a 30-year-old woman, preoperative AP view. b The same patient, 1 year after left THA with alumina bearing couple, AP view. c The same patient, 1 year postoperatively, lateral view. d The same patient, 4 years postoperatively, AP view

Furthermore, the fact that in our study group the patients were considerably younger did not compromise the set goal parameters of the study. On the contrary, it could even be argued that the slightly older age of the patients tended to make the use of metal-polyethylene implants favourable to wear exposure (older, less active patients). However, today it is known that age is neither the only nor the major parameter in the development of endoprosthetic system wear. The number of cycles annually by an artificial joint primarily depends of the level of activity. Even under such conditions (young, very active patients), the alumina/alumina endoprosthetic system did not show disadvantages.

The results of our study, with a mean follow-up of 50.4 months, on arthroplastic surgery are considered early, but for the time being they are excellent. The comparative analysis of the relevant parameters of the two identical endoprosthetic systems with different bearing couples proved both systems to be highly reliable.

In the analysis of clinical parameters defined according to the HHS, 95% of excellent and good results were accomplished in both groups tested: 96% in the study group and 94% in the control group. Similar results were presented by D’Antonio et al. [7] and Capello et al. [4].

The parameters referring to the complications and radiographic evaluation of mechanical stability of implants showed that the rate of revisions was very low, with a total of 1% (two cases). In addition, of a total of 157 implants, only one implant was revised due to mechanical instability of the endoprosthetic component within the first year of follow-up. The second revision was done for recurrent dislocation.

Small cortical erosions of the femoral zones 1 and 7 in the study group were encountered only in two cases (2%), while in the control group it was found in eight (11%). Nevertheless, the difference in the incidence was not statistically significant. Capello et al. reported cortical lesions in the zone of femoral neck resection to be statistically significantly rarer in the ceramic group of implants [4]. They consider that this confirms the hypothesis proposed in their earlier study that such lesions are the result of considerably higher release of debris chips than in the metal-polyethylene group [6]. This could also be the explanation for a rather more frequent incidence of cortical erosions in the proximal femoral zones of the control group implants in our study. The reason for the lack of significant statistical significance of this difference is probably due to the use of the HXLPE in our study, while in the study of D’Antonio et al. conventional polyethylene was used [6]. Five years is obviously not sufficient for the HXLPE to reveal failure that can be noted during its prolonged use, which is being reported by groups of authors for the third decade of use [9, 17, 20].

As expected from early results on stems with a calcar collar, subsidence of the stem did not occur in any of the group of implants.

Pedestal formation around and below the top of the femoral component was noted in both groups, without statistical significance with regard to frequency. The pedestals were seen in a total of 32 cases (20%), of whom 28 (86%) had characteristics of a stable stem, while the patients were asymptomatic. As such a radiographic sign is used in the evaluation of global stem stability, and having in mind that in our material most of the stems were radiographically and all clinically stable, the pedestal was not under consideration as a relevant sign in the evaluation of durability of the endoprosthetic system.

In two cases it was necessary to perform a revision of the endoprosthetic system. Due to aseptic loosening, a varus placed stem had to be exchanged with a modular revision system. The second revision was done for recurrent dislocation. All dislocations (three in total, 2%) were first non-operatively repositioned under regional anaesthesia. One recurred and was thus treated by revision surgery: the standard CoCr/HXLPE bearing couple (28 mm head/0° liner inclination) was exchanged with a bearing couple of higher stability and extent of motion (32 mm/10°). The metal components of the implant were not removed as there were no significant irregularities in their orientation.

The problem of ceramic acetabular liner damaged by chipping, which occurred in three cases in our study, has also been reported by other authors [4, 7]. Namely, the insertion of a ceramic liner into the metal acetabular ring requires great attention and precision. The impaction of an irregularly placed liner results in edge fracture with detachment of smaller or larger chips, which may also spread to the articular surface. In two cases we intraoperatively exchanged the damaged ceramic with a new one, while one stable liner with undamaged articular surface was left within the ring. A similar problem and solution has been reported by other authors [4].

The fibre metal-coated acetabular component was shown to be most reliable, although in three cases an RLL was noted in zone 1 and in zones 2 and 3 less frequently (1% and 2%, respectively). These components were classified as fibrous stable and have not become symptomatic during follow-up up to now.

Incomplete cracking of the femur in the trochanteric and subtrochanteric regions, occurring during stem insertion, was resolved by cable cerclage, without stem removal.

In our study, there was no deep infection. This fact could not be considered a great success or surprise, having in mind the relative youth and good health of the patients, as well as the fact that all surgeries were performed in operating theatres with sterile airflow. Our data are not greatly different from the results of other authors [4, 7].

Finally, it should be pointed out that the five-year duration of our study is not sufficient to pass a true judgment on the durability of implants. Namely, negative characteristics of the endoprosthetic material and design manifest only after ten years of use, when the survival of the artificial joint significantly decreases [14, 15].

In the five-year follow-up of young and very active patients, in the groups tested we did not encounter great differences in reliability and durability. It can be concluded that in the endoprosthetic systems tested, the bearing couples of the third generation of alumina ceramics did not manifest deficiencies characteristic of previously used ceramics. On the contrary, they appear to be fully reliable and identical to CoCr/HXLPE couples.

The durability of this ceramic endoprosthetic system will only be confirmed after a follow-up of over 15 years. The potential of the new alumina ceramics seems high and especially suited for hip arthroplasty in young and active persons.

References

- 1.Bragdon C, O’Connor D, Lowenstein J, Jasty M, Syniuta W. The importance of multidirection motion on the wear of polyethylene. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 1996;210:157–165. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_408_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bragdon C, Jasty M, Muratoglu O, O’Connor D, Harris W. Third-body wear of highly cross-linked polyethylene in a hip simulator. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:553–561. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaway G, Flynn W, Ranawat C, Sculco T. Fracture of the femoral head after ceramic-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:855–859. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(05)80087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capello W, D’Antonio J, Feinberg J, Manley M, Naughton M. Ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty: update. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7 Suppl):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke I. Role of ceramic implants. Design and clinical success with total hip prosthetic ceramic-to-ceramic bearings. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;282:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Antonio J, Capello W, Manley M. Remodeling of bone around hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1226–1234. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199608000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Antonio J, Capello W, Manley M, Bierbaum B. New experience with alumina-on-alumina ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:390–397. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLee J, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowsher J, Williams P, Clarke I, Green D, Donaldson T. “Severe” wear challenge to 36 mm mechanically enhanced highly crosslinked polyethylene hip liners. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;86:253–63. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engh C, Massin P, Suthers K. Roentgenographic assessment of the biologic fixation of porous–surfaced femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;257:107–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruen T, McNeice G, Amstutz H. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris W. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klisic P, Rakic D, Pajic D, Parezanovic V. Prevention, care and screening of hips of newborn infants (in French) Acta Orthop Belg. 1990;56:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malchau H, Henberts P, Ahnfelt L. Prognosis of total hip replacement in Sweden. Follow-up of 92,675 operations performed 1978–1990. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:497–506. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malchau H, Garellick G, Eisler T, Kärrholm J, Herberts P. Presidential guest address: the Swedish Hip Registry: increasing the sensitivity by patient outcome data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:19–29. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000193517.19556.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKellop H, Shen F, DiMaio W, Lancaster JG. Wear of gamma-crosslinked polyethylene acetabular cups against roughened femoral balls. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:73–82. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mu Z, Tian J, Wu T, Yang J, Pei F. A systematic review of radiological outcomes of highly cross-linked polyethylene versus conventional polyethylene in total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2009;33:599–604. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0716-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramamurti B, Bragdon C, O’Connor D, Lowenstein J, Jasty M, Estok D, Harris W. Loci of movement of selected points on the femoral head during normal gait. Three-dimensional computer simulation. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:845–852. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramamurti B, Estok D, Jasty M, Harris W. Analysis of the kinematics of different hip simulators used to study wear of candidate materials for the articulation of total hip arthroplasties. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:365–369. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakoda H, Voice A, McEwan M, Isaak G, Hardaker C, Wroblewski B, Fisher J. A comparison of the wear and physical properties of silane cross-linked polyethylene and ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:1018–1023. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.27234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor S, Manley MT, Sutton K. The role of stripe wear in causing acoustic emissions from alumina ceramic-on-ceramic bearings. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7 Suppl 3):47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vukasinović Z, Vucetić C, Cobeljić G, Bascarević Z, Slavković N. Developmental dislocation of the hip is still important problem—therapeutic guidelines (in Serbian) Acta Chir Iugosl. 2006;53:17–19. doi: 10.2298/ACI0604017V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vukasinović Z, Zivković Z, Vucetić C. Developmental hip dysplasia in adolescence (in Serbian) Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2009;137:440–443. doi: 10.2298/SARH0908440V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willmann G. Ceramic femoral head retrieval data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;379:22–28. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]