Abstract

The aim of the prospective cohort study was to investigate the outcome of acute whiplash injury first treated either by junior doctors (JD) [≤3 postgraduate years (PGY)] or more experienced doctors (MED) (>3 PGY). At baseline, crash-related data and health parameters including the SF36 were evaluated in whiplash patients (WP), who fulfilled criteria for whiplash-associated disorders grade I–II and presented up to 48 h after motor vehicle accident to our Emergency Department. 81 WP were recruited and treated by either one of 14 JD (35 WP) or one of 22 MED (46 WP). The follow-up examination included the course of pain intensity [numeric rating scale (NRS) 0–10] by the use of a 28 days-pain-diary and the incidence of symptoms (standardized-telephone-interview at 1, 3, and 6 months post trauma) in terms of neck pain NRS > 2, analgesic medication, work-off, and utilization of further medical services as well as SF36 evaluated at the end of the study. Although the entry population seemed similar, all outcome parameters were comparable between the JD- and MED-group (p > 0.05). Therefore, we conclude that seniority of the first-treating physician does not influence the outcome of acute whiplash injury.

Keywords: Whiplash, Neck injury, Emergency department, Junior doctor, Seniority

Introduction

Whiplash, also called whiplash-associated disorders (WAD), is the most common injury following motor vehicle crashes [1, 2]. The majority are minor injuries and defined as WAD I and II (neck stiffness/pain without instability or neurological deficit) [1]. Nevertheless, permanent disability is a common occurrence after whiplash injury and associated with high socioeconomic costs [2].

A wide range of potential prognostic factors have been considered to influence the development of prolonged symptoms revealing conflicting results on the relative importance of crash, demographic, physical, psychological and sociocultural factors [1, 3–7]. Furthermore, an effective guideline to avoid prolonged whiplash injury-associated pain and disability is still under scientific debate [8–10].

It is well known that in emergency care seniority of the first-treating physician has a significant beneficial influence on the outcome of major trauma [11]. Although the Quebec Task Force recommended specialized medical care in acute whiplash injury almost 15 years ago, there is still a lack of information whether first-treating physicians with advanced medical experience have also a positive effect on the result of whiplash injury care [1]. Therefore, we conducted a prospective study investigating the importance of clinical experience of the first-treating doctor on the outcome of whiplash patients (WP) in the emergency department (ED).

Materials and methods

This prospective cohort study was carried out at the Department of Trauma Surgery, University Hospital of Munich, Campus Grosshadern and was approved by the local ethical committee.

Participating physicians

For the purpose of this study, doctors with a clinical experience up to their third postgraduate year (PGY) were defined as junior doctors (JD) and those after the third PGY as more experienced doctors (MED). Out of 65 physicians who are employed in our department, 36 were enrolled as they treated patients with acute whiplash injury during the study period of 23 months. There were 5 female and 9 male physicians in the JD group (38.9%) and 5 female and 17 male in the MED group (61.1%) (p = 0.396). The JD group included 6 intern beginners (up to 1.5 PGY) (42.9%) and 8 advanced interns (1.5–3 PGY) (57.1%), whereas the MED group implied 8 residents (3–6 PGY) (36.4%) and 14 doctors with clinical experience of more than 6 PGY (63.6%). This subgroup contained seven senior physicians specialized in surgery and/or trauma surgery (31.8%).

Participating patients

Whiplash patients were recruited at the ED of our hospital, gave informed consent for enrollment to the study and were treated as outpatients. They filled out the baseline form including (1) health parameters like body mass index (BMI), incidence of “previous neck pain” and SF36, an instrument which was used already in a previous study to determine patients’ health status in whiplash injury [12]. (2) Sociodemographic parameters contained the “educational status”, which was rated as “high” when the WP had graduated the senior high school level and the “income status” was stratified as “own” in employees/self-employed persons, whereas all others as “no own”. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria selecting study patients

| Study criteria |

|---|

| Inclusion |

| Patients suffering from WAD grade I and II after vehicle collision |

| Exclusion |

| Patients being younger than 18 and older than 75 years |

| Patients arriving at the ED >48 h after collision |

| Patients having consulted another physician before presentation at ED |

| Patients suffering AIS 2 + injury; WAD > II; unconsciousness; amnesia |

| Patients complaining severe disease or chronic pain before WAD |

| Patients without knowledge of German language |

| Patients refusing study participation |

Crash analysis

Collision analysis was performed by the co-author (JB) who is a technical engineer with accredited experience and who was blinded to the medical data. Parameters were generated from baseline questionnaire, ED protocol, police report and car repair shop data. The principal direction of impact was stratified to “longitudinal” (rear and front collisions) whereas other crash-types like side or multiple collisions to “not longitudinal”. The collision severity is documented by “delta-v”, which can be defined by (1) analyzing the crash vehicle, (2) specifying the energy of deformation and (3) performing calculations based on the “principle of linear momentum”. As delta-v is a parameter, which represents the change of velocity and determines the acceleration which acts onto the passenger’s body during the collision, delta-v is used as one predictor for the probability of occupant injury and utilized most widely in crash databases [13].

Diagnostics and treatment-structure

In the ED, clinicians had to work up a clinical and radiographic investigation matrix to determine the grade of WAD [1]. Whiplash treatment strategies were not prescribed and doctors were not informed about the trial until the end of the study. The recruitment analysis showed, that 35 WP (43.7%) were treated by 14 JD (38.9%) (treatment ratio WP/JD = 2.5; range 1–6) whereas 46 WP (56.8%) were seen by 22 MED (61.1%) (treatment ratio WP/MED = 2.1; range 1–6) (t test p = 0.455). Doctors’ applied treatment strategies were stratified by the prescription of analgesic medication and work-off. Additionally, as a measurement of neck immobilization, the incidence of soft-collar prescription was documented in both groups.

Follow-up

Documentation of neck pain intensity by a 28-days-pain-diary using the 11-points numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0 (no pain) up to 10 (worst possible pain intensity) is a validated instrument for measurement of recovery in whiplash injury [14]. The diary was explained and handed out to the patients at the end of consultation by the doctor.

Further follow-up investigations were performed by the co-author (TW) who was not involved into the therapy and was blinded concerning identification of first-treating doctor and crash-data. During the initial posttraumatic week, the investigator contacted the WP using a standardized “baseline telephone interview” to evaluate the quality of the following items concerning the doctor’s performance during ED consultation. (1) The “atmosphere of interpersonal interaction” between patient and doctor was rated as “poor” when the WP declared that the consultation had been characterized by non-dedication or other types of unprofessionalism. (2) The “educational performance” reflected the quality of provided whiplash injury background information concerning not only the explanation of the injury mechanism but also a differentiated statement concerning possible treatment strategies (e.g. immobilization versus early return to act-as-usual behavior) and their possible effect on expected outcome. (3) The “advice for activities of daily life” (ADL) characterized doctor’s recommendation in terms of an immediate posttraumatic return to normal ADL-standard or in contrast, in terms of a protective referral meaning a reduced ADL-level including physical rest.

1, 3, and 6 months after collision, the blinded investigator contacted the WP utilizing the standardized “follow-up telephone questionnaire” to obtain additional outcome data associated with whiplash injury. (1) “neck pain (NRS > 2)”, meaning that at least once per week whiplash-associated neck pain of an intensity of NRS > 2 hinders the victim to perform normal activities of daily life; (2) “analgesic drug usage” contain the information that whiplash-related neck pain squeezed the WP to take pain killers at least once per week; and (3) “inability to work” documented the fact that the WP complaint being unable to work because of whiplash injury-related problems for at least half of the time between trauma and interview; (4) the item “further medical help” aimed to collect information whether the WP was not elongated affected by the injury and consequently did not visit any further medical services after the ED contact or in contrast, whether an additional physician and/or a physiotherapist was consulted at any stage during the study period because of whiplash-related indications. The interviews were structured and in case of any open points these were directly discussed with the patients during the telephone interview in order to certify that the responds were placed to the correct category. Finally, the SF36-questionnaire was used to evaluate the health status at the end of the study indicating the quality of whiplash injury-recovery in both groups.

Statistical methods

For the comparison of both groups the Fisher’s exact test and t test were used to evaluate the differences of baseline data where needed. The Spearman Rank Correlation was utilized to analyze the association between several factors and outcome parameters. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied for the assessment of not normally distributed results, e.g. the intensity of pain (NRS) during the first month after collision. SPSS® 15.0 for windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses. Level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Participating patients

Out of 235 WP, 137 had to be excluded because they did not meet the study criteria. (1) 29 victims had already seen another physician for whiplash injury treatment or arrived later than 48 h after collision or were younger than 18 or older than 75 years; (2) 48 patients suffered more severe injuries during crash (AIS 2 + injury; WAD > II) or unconsciousness/amnesia; (3) 39 subjects complained of pre-traumatic either severe somatic/psychiatric diseases or chronic pain syndrome; and (4) 21 patients did not understand German or refused study participation. As 3 WP could not be reached for follow-up investigation, 6 WP had an incomplete follow-up data-set and 8 WP had an incomplete crash-data-set, a total number of 81 acute WAD victims were recruited for this study. The drop-out analysis showed that subjects allocated for the study did not differ from those who were lost for follow up with respect to demographic/social/medical/SF36 data and initial presenting symptoms.

Sixty-one WP (75.3%) arrived at the ED in less than 12 h after collision. Mean age of participants was 33.0 years (SD = 12.0, range 18–74), 45 victims (55.6%) were female with a mean BMI value of 23.6 (SD = 3.6, range 17.0–35.7). The mean baseline SF36-scores showed for the physical component summary (PCS) a value of 48.8 ± 7.7 and for the mental component summary (MCS) a measurement of 51.0 ± 7.6. Baseline values concerning patients’ data showed no difference between both groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline data of 81 whiplash patients first treated either by junior doctors (JD group) or more experienced doctors (MED group)

| Factor | Category | JD group | MED group | All patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient data | ||||

| Time to hospitala | ≤12 h | 29 (82.9) | 32 (69.6) | 61 (75.3) |

| >12–48 h | 6 (17.1) | 14 (30.4) | 20 (24.7) | |

| Agea | 18–44 years | 26 (74.3) | 38 (82.6) | 64 (79.0) |

| 45–75 years | 9 (25.7) | 8 (17.4) | 17 (21.0) | |

| Gendera | Male | 18 (51.4) | 18 (39.1) | 36 (44.4) |

| Female | 17 (48.6) | 28 (60.9) | 45 (55.6) | |

| Body mass indexa | ≤25.0 kg/m2 | 23 (65.7) | 34 (73.9) | 57 (70.4) |

| >25.0 kg/m2 | 12 (34.3) | 12 (26.1) | 24 (29.6) | |

| Previous neck paina | No | 34 (97.1) | 42 (91.3) | 76 (93.8) |

| Yes | 1 (2.9) | 4 (8.7) | 5 (6.2) | |

| Education statusa | High | 13 (37.1) | 16 (34.8) | 29 (35.8) |

| Low | 22 (62.9) | 30 (65.2) | 52 (64.2) | |

| Income statusa | No own | 15 (42.9) | 17 (37.0) | 32 (39.5) |

| Own | 20 (57.1) | 29 (63.0) | 49 (60.5) | |

| SF36 (mean ± SD) | PCS | 48.9 ± 8.9 | 48.7 ± 8.3 | 48.8 ± 7.7 |

| MCS | 50.6 ± 8.3 | 51.2 ± 7.2 | 51.0 ± 7.6 | |

| Accident data | ||||

| Direction of impacta | Longitudinal | 27 (77.1) | 36 (78.3) | 63 (77.8) |

| Not longit. | 8 (22.9) | 10 (21.7) | 18 (22.2) | |

| Delta-va | ≤20 km/h | 20 (57.1) | 24 (52.2) | 44 (54.3) |

| >20 km/h | 15 (42.9) | 22 (47.8) | 37 (45.7) | |

| Seating positiona | Driver | 25 (71.4) | 37 (80.4) | 62 (76.5) |

| Occupant | 10 (28.6) | 9 (19.6) | 19 (23.5) | |

| Belt usagea | Belted | 34 (97.1) | 46 (100) | 80 (98.8) |

| Not belted | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Airbag deploymenta | Deployed | 2 (5.7) | 5 (10.9) | 7 (8.6) |

| Not deployed | 33 (94.3) | 41 (89.1) | 74 (91.4) | |

aData are given as number of whiplash patients. Percentages are shown in parentheses

Statistical analysis (Fisher’s exact- or t tests were needed with p < 0.05) was performed but there were no significant differences between both groups

Crash analysis

Most of the crashes were rear end [n = 46 (56.8%)] or front collisions [n = 17 (21.0%)]. None of the crashes had a higher change of velocity than 40 km/h. As shown in Table 2, crash-data did not differ in both groups.

Quality of doctor–patient interaction, education, and applied therapy

The majority of WP (92.6%) rated the “atmosphere of interaction” with the doctor during consultation as “normal”. In contrast, only 28 WP (34.6%) explained that the “educational performance” was “sufficient” and although statistically not significant, a higher percentage of WP in the JD group (40.0%) when compared with the MED group (30.4%) were content with this physician-related parameter. Only 13 WP (13.0%) were advised to perform normal ADL after trauma and additionally, most of the WP received pain killers (90.1%), were declared as incapable to work (77.8%) and got cervical immobilization by soft-collar prescription (51.9%). These items did not show a difference between both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quality of physician–patient interaction, education, and advice for ADL/neck immobilization in 81 whiplash patients first-treated either by junior doctors (JD group) or more experienced doctors (MED group)

| Factor | Category | JD group | MED group | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere of interpersonal interaction | Normal | 32 (91.4) | 43 (93.5) | 1.000 |

| Poor | 3 (8.6) | 3 (6.5) | ||

| Educational performance | Sufficient | 14 (40.0) | 14 (30.4) | 0.480 |

| Not sufficient | 21 (60.0) | 32 (69.6) | ||

| Advice for activities of daily life | Normal | 6 (17.1) | 7 (15.2) | 1.000 |

| Reduced | 39 (84.8) | 29 (82.9) | ||

| Prescription of analgesic medication | No | 4 (11.4) | 4 (8.7) | 0.721 |

| Yes | 31 (88.6) | 42 (91.3) | ||

| Prescription of work-off | No | 8 (22.9) | 10 (21.7) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 27 (77.1) | 36 (78.3) | ||

| Prescription of soft-collar | No | 16 (45.7) | 23 (50.0) | 0.823 |

| Yes | 19 (54.3) | 23 (50.0) |

Data are given as number of whiplash patients. Percentages are given in parentheses

* p values were evaluated by the use of the Fisher’s exact test

Follow-up data I

Pain intensity (NRS) during 28 days after collision

At baseline, the median neck pain intensity NRS was 5.00 ± 2.54. The intensity decreased continuously during the first 28 days after trauma to a median NRS of 1.63 ± 1.78 and the highest degree of reduction occurred between day 7 (4.05 ± 2.35) and 14 (2.95 ± 2.12) (22%). WP of the MED group rated the intensity of initial neck pain to less high values (median 5.00 ± 2.32) when compared to those of the JD group (6.00 ± 2.82) and recovery during the first month after trauma reached a slightly lower median value in the MED group (1.64 ± 1.57) when compared with the JD group (1.96 ± 1.88), but there was no significant difference detectable between both study groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pain intensity (numeric rating scale) during 28 days after MVA of 81 whiplash patients first-treated either by junior doctors (JD group) or more experienced doctors (MED group)

| JD group | MED group | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity (days) | |||

| 1 | 6.00 ± 2.82 | 5.00 ± 2.32 | 0.664 |

| 7 | 4.50 ± 2.59 | 3.69 ± 2.15 | 0.418 |

| 14 | 3.14 ± 2.35 | 2.85 ± 1.93 | 0.486 |

| 21 | 2.18 ± 2.16 | 2.10 ± 1.80 | 0.561 |

| 28 | 1.88 ± 1.96 | 1.57 ± 1.64 | 0.640 |

Data are given as median and standard deviation

* p values were evaluated by the use of the Mann–Whitney U test

Follow-up data II

Incidence of neck pain, SF36-evaluation, duration of analgesic medication and work-off, and further utilization of medical services after first consultation

Three months after onset of symptoms, eight victims were still distressed by whiplash injury-related neck pain with an intensity of NRS > 2 (9.9%). Thereafter, the incidence of considerable neck pain kept unchanged until the end of the study period. However, the comparison of both groups concerning the incidence of severe neck pain showed no significant difference 1, 3 and 6 months after collision (Table 5).

Table 5.

Follow-up data of 81 whiplash patients first-treated either by junior doctors (JD group) or more experienced doctors (MED group)

| JD group | MED group | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck pain (NRS > 2) | |||

| 1 month | 13 (37.1) | 12 (26.1) | 0.336 |

| 3 months | 5 (14.3) | 3 (6.5) | 0.282 |

| 6 months | 5 (14.3) | 3 (6.5) | 0.282 |

| Analgesic drug usage | |||

| 1 month | 8 (22.9) | 4 (8.7) | 0.114 |

| 3 months | 5 (14.3) | 2 (4.3) | 0.230 |

| 6 months | 3 (8.6) | 2 (4.3) | 0.647 |

| Duration of work-off | |||

| 1 month | 5 (14.3) | 3 (6.5) | 0.282 |

| 3 months | 3 (8.6) | 2 (4.3) | 0.647 |

| 6 months | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.2) | 0.575 |

Data are given as number of whiplash patients. Percentages are given in parentheses

* p values were evaluated by the use of the Fisher’s exact test

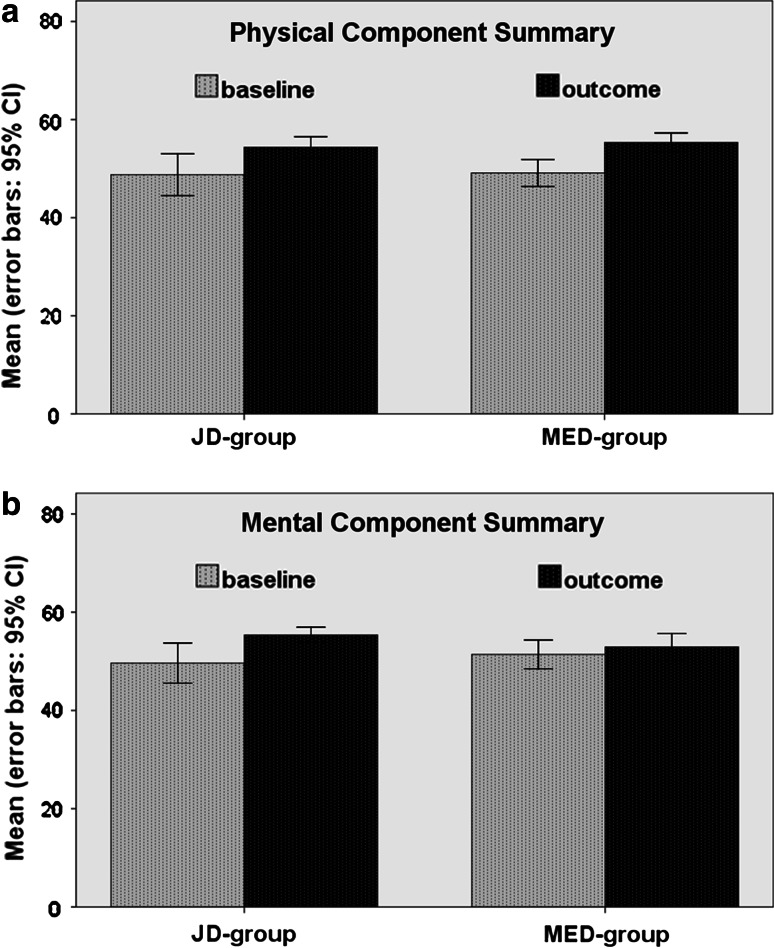

There was an overall improvement of the health status observable during the study period evaluated by the SF36 changes. At the end of the study, the PCS was 53.5 ± 5.2 in the JD group and 55.6 ± 5.2 in the MED group, whereas the MCS was 55.0 ± 4.3 in the JD group compared to 53.9 ± 6.5 in the MED group (t test, PCS p = 0.185; MCS p = 0.221). In accordance to these results, the analysis of SF36 changes between baseline values and those reported at the end of the study, again were comparable in both groups (t test, PCS p = 0.741; MCS p = 0.117) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

SF-36 at baseline and outcome: a physical component summary, b mental component summary

The usage of analgesic drugs taken for the purpose to reduce whiplash injury-related pain continuously decreased during the first 6 months after onset of symptoms. 1 month after collision, still 12 WP (14.8%) took pain killers compared to 5 WP (6.2%) 6 months after trauma. The Spearman Test showed a strong correlation between the duration of analgesic medication and whiplash-related neck pain intensity during the whole study period (p < 0.01). Although statistically not significant, slightly more WP of the JD group were in need of analgesic medication during the study period (Table 5).

The incidence of whiplash injury-related work-off continuously decreased during the first half-year after collision. 1 month after whiplash injury, eight WP (9.9%) still were incapable to work, whereas 6 months after trauma there were three WP left (3.7%). Again, the Spearman Test showed a strong correlation between the incidences of neck pain NRS > 2, analgesic medication and work-off during the study period (p < 0.01). Not showing a significant difference, there were still two WP in the JD group (5.7%) when compared with one WP in the MED group (2.2%) claiming whiplash-related work-inability at the end of the study period (Table 5).

Thirty-five WP (43.2%) did not seek for any further whiplash injury-related medical help after the ED consultation during the first 6 months after trauma. From the remaining WP, 13 victims (16.1%) were looking for further medical help visiting another physician, which was in the vast majority their family doctor. Additionally, 33 WP (40.7%) consulted not only another physician but also a physiotherapist for treatment of WAD. The Spearman Test showed a strong correlation between the incidence of severe neck pain (NRS > 2) according the 28 days-pain dairy and the utilization of further medical help. Those WP indicating low initial neck pain levels required no further medical help and vice versa, severe initial neck pain led to a significantly elevated utilization of health care facilities in terms of physician and physiotherapist consultation (p < 0.01). But there was no difference between WP treated by the JD group and those treated by the MED group concerning their utilization-behavior of medical services during the study period (Table 6).

Table 6.

Utilization of further medical services in 81 whiplash patients first-treated either by junior doctors (JD group) or more experienced doctors (MED group)

| Further medical help | JD group | MED group | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 13 (37.1) | 22 (47.8) | 0.372 |

| Only physician | 8 (22.9) | 5 (10.9) | 0.221 |

| Physician and physiotherapist | 14 (40.0) | 19 (41.3) | 0.544 |

Data are given as number of whiplash patients. Percentages are given in parentheses

* p values were evaluated by the use of the Fisher’s exact test

Discussion

There is no study available investigating the influence of the first-treating doctor’s stage of clinical experience on the outcome in acute whiplash injury. However, we identified in the pre-phase of this study several indicators leading to our hypothesis that seniority of the first-treating ED doctor affects the outcome of whiplash injury

First, Cantwell et al. [15] showed that JD have incompletely developed skills in doctor–patient communication and additionally, Bovier et al. [16] demonstrated that JD are concerned about bad outcome and have significantly greater anxiety due to uncertainty when compared with physicians with advanced seniority. These attributes are most probably aggravated in the treatment of acute whiplash injury as it is well known that physician’s stress load is substantially higher in an emergency department when compared with other hospital units [17, 18].

Second, numerous investigations showed that a junior doctor is not only a responsible health professional but also a learner and concluded that early trauma management should be performed by more experienced physicians in order to optimize victim’s recovery [11, 19, 20].

Third, WP can suffer from acute psychological stress related to the collision that is positively associated with a worsening outcome and furthermore, Richter et al. [12, 21] showed that psychological factors are even more relevant than collision severity in predicting the duration as well as severity of symptoms in WAD grade I or II.

As shown by the studies mentioned above, JD might be overcharged due to uncertainty and concern about bad outcomes and therefore are unable to calm down WP-elevated psychological alterations associated with acute whiplash injury [12, 15, 16, 18, 21]. Therefore, we hypothesized vice versa that the availability of advanced medical skills of MED lead to a substantially more qualified doctor–patient interaction and therefore to a superior outcome in WP first-treated in an emergency department.

However, analyzing the results of the study, we had to refuse the hypothesis as not only doctor’s performance and applied treatment strategies were comparable in both groups but also WP treated by MED group had no superior outcome concerning intensity and duration of whiplash-related symptoms.

In detail, the vast majority of WP classified the interaction as “normal”, but two-thirds of these rated the educational characteristics of the emergency-physician as “not sufficient”. This might be explained by the fact that based on the elevated workload in emergency departments, there is only a low level of medical time investment available for the treatment of minor injuries like whiplash injury [17–19]. Anyhow, we detected a non-significant superior educational attitude of JD, which is likely to be explained by the well-known fact that JD spend more time talking to patients in emergency care [22]. But overall, interaction and education was almost similar in both groups. Planning the study, we refused to prescribe a standardized treatment strategy as (1) this advocacy probably would have influenced the physicians’ performance during consultation and (2) during this phase, there was still a scientific debate about the ideal strategy to prevent long-term symptoms in whiplash injury [8]. In this context, it is remarkable on the one hand that the applied treatment strategies were very similar in both groups concerning given advice for the ADL level after the trauma and prescription of analgesic medication, work-off and cervical immobilization. Hence, this result is in accordance with another trial, showing that JD adopt a wide range of therapeutic recommendations from their senior colleagues [22]. On the other hand, the results showed that during the study period, the majority of the physicians tend to a cervical immobilisation and reduced activity level after the accident as whiplash treatment which is not in line with current recommended advice and treatment in acute WAD grades 1 and 2 [10]. It is possible that these passive treatments applied by senior and junior staff might have resulted in equally poor outcomes, overwhelming any seniority effect. However, we set out to investigate practice in a busy accident and emergency department, and so we compared the practice of JD with that of MED operating in the same department. We did not attempt to audit practice against published guidelines.

In the present study, 3 and 6 months after accident, 9.9% of all WP suffered at least moderate neck pain intensity (NRS ≥ 3). Although this incidence is difficult to compare to the literature—as there are multiple methods categorizing the course of neck pain after whiplash injury—there is some evidence that this rate is relatively low [7, 23]. This might be due to the fact that our cohort exclusively consisted of victims with non-life-threatening injuries (AIS ≤ 2; WAD I/II) who originated from motor vehicle collision with low crash severity (delta-v < 40 km/h). Those patients complaining severe pain intensity at 3 months did not recover until the end of the study (9.9%) and severe pain intensity was highly correlated to the incidences of analgesic drug usage and inability to work. Again, including the SF36 change from beginning to the end of the study, there was no superior outcome in WP treated by the MED group (p > 0.05). Additionally, the incidence of NRS > 2 pain intensity during the first month after injury was strongly associated with prolonged pain symptoms. This observation is in accordance to other studies, showing that early susceptibility to elevated pain intensity is a prognostic factor in whiplash injury and as in the present study the baseline parameter “previous neck pain” was significantly correlated to “neck pain NRS > 2” 6 months after trauma (Spearman Correlation p = 0.02). Hereby, we assume that pre-collision health conditions influence the rate of late whiplash syndrome [12, 24].

Nowadays, JD are implemented as responsible health professionals in emergency care because of an increasing number of patients and a limited availability of experienced medical staff [11, 18, 19]. This phenomenon was also present in our study as the number of WP treated by one physician was higher in the JD group when compared with the MED group (factor 1.20). There are investigations showing the dilemma that saving specialization in the early stage of health care can cause elevated effort at a later stage of disease and consequently can increase health care costs [17, 19]. Fortunately, we did not observe this effect in the first therapy of acute whiplash injury as there was no difference between both groups concerning the seeking-behavior for additional medical help.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of the present study include first the unequal size of study groups and the lack of randomization caused predominately by the limited availability of JD. At the time of the study, 1–2 JD and 6 MED were working regularly in the ED during the normal working hours (Monday–Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m.) and during the rest of the time three doctors were covering the ED including up to 1 JD. Nevertheless, allocation of WP to one of both study groups was dependent on the availability of a JD or a MED when the WP showed up in the emergency department. Therefore, allocation was unbiased by the investigators. Additionally, as at baseline, there was no significant difference between the study groups concerning potential prognostic demographic and crash factors (Table 2), the entry population seemed similar and therefore, this potential bias was minimized.

Second, there might be an investigator-based bias influencing the results of the study. Since pain (NRS) was self-assessed by patients and all follow-up investigations were performed by a research assistant who (1) did not intervene to the treatment and (2) was blinded regarding the first-treating physician, a potential assessor-related bias could be minimized. Third, the small number of patients involved in the study is a weakness of the study. Since the sample size was too small to do an adequate multivariable model to adjust for baseline differences, the results are based on a crude (unadjusted) comparison.

In summary, WP did not benefit by the first treatment of a MED (>3 PGY) in comparison to therapy performed by junior doctor (≤3 PGY) since intensity and duration of symptoms were comparable in both groups. Therefore, with the figures available, we conclude that the seniority structure of the emergency department personnel can keep unchanged for whiplash injury treatment. Nevertheless, the trends seen in the results favoring the senior doctors is concerning because the study is relatively small. We had to reject the hypothesis because the statistical level set was not reached but this might be an error generally seen in under-powered studies. Therefore, there is a need for further in-depth multicenter-investigations to get validated information about prognostic factors in whiplash injury in order to avoid long-term symptoms and to reduce the tremendous socio-economic burden of whiplash injury.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was corrected for proper English by Wolfgang Böcker, MD.

Conflict of interest statement

No funding was received from any organization for this work.

Contributor Information

Oliver Pieske, Phone: +49-89-70950, FAX: +49-89-70955424, Email: Oliver.Pieske@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Toralf Weinhold, Email: Toralf.Weinhold@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Jochen Buck, Email: dr.buck@gmx.de.

Stefan Piltz, Email: Stefan.Piltz@med.uni-muenchen.de.

References

- 1.Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, Cassidy JD, Duranceau J, Suissa S, Zeiss E. Scientific monograph of the Quebec task force on whiplash-associated disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine. 1995;20:1S–73S. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinlan KP, Annest JL, Myers B, Ryan G, Hill H. Neck strains and sprains among motor vehicle occupants-United States, 2000. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36:21–27. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C. A systematic review of the prognosis of acute whiplash and a new conceptual framework to synthesize the literature. Spine. 2001;26:E445–E458. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200110010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholten-Peeters GG, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, van der Windt DA, Barnsley L, Oostendorp RA, Hendriks EJ. Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Pain. 2003;104:303–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams M, Williamson E, Gates S, Lamb S, Cooke M. A systematic literature review of physical prognostic factors for the development of Late Whiplash Syndrome. Spine. 2007;32:E764–E780. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b6565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson E, Williams M, Gates S, Lamb SE. A systematic literature review of psychological factors and the development of late whiplash syndrome. Pain. 2008;135:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, Peloso PM, Guzman J. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S83–S92. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643eb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhagen AP, Scholten-Peeters GG, van Wijngaarden S, de Bie RA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM (2007) Conservative treatments for whiplash. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Gross AR, Goldsmith C, Hoving JL, Haines T, Peloso P, Aker P, Santaguida P, Myers C. Conservative management of mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1083–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, Nordin M, Guzman J, Peloso PM, Holm LW, Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S (2008) Treatment of neck pain: noninvasive interventions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33:S123–S152 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wyatt JP, Henry J, Beard D. The association between seniority of accident and emergency doctor and outcome following trauma. Injury. 1999;30:165–168. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(98)00252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter M, Ferrari R, Otte D, Kuensebeck HW, Blauth M, Krettek C. Correlation of clinical findings, collision parameters, and psychological factors in the outcome of whiplash associated disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:758–764. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.026963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabauer DJ, Gabler HC. Comparison of roadside crash injury metrics using event data recorders. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vangronsveld KL, Peters M, Goossens M, Vlaeyen J. The influence of fear of movement and pain catastrophizing on daily pain and disability in individuals with acute whiplash injury: a daily diary study. Pain. 2008;139:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantwell BM, Ramirez AJ. Doctor–patient communication: a study of junior house officers. Med Educ. 1997;31:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bovier PA, Perneger TV. Stress from uncertainty from graduation to retirement—a population-based study of Swiss physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:632–638. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armitage M, Flanagan D. Improving quality measures in the emergency services. J R Soc Med. 2001;94(Suppl 39):9–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin S, Aronsky D, Hemphill R, Han J, Slagle J, France DJ. Shifting toward balance: measuring the distribution of workload among emergency physician teams. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiticar R, Webb H, Smith S. Re-attendance to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:360–361. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.050617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer AJ, Hollander JE, Valentine SM, Thode HC, Jr, Henry MC. Association of training level and short-term cosmetic appearance of repaired lacerations. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:378–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kongsted A, Bendix T, Qerama E, Kasch H, Bach FW, Korsholm L, Jensen TS. Acute stress response and recovery after whiplash injuries. A one-year prospective study. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones J, Sanderson C, Black N. What will happen to the quality of care with fewer junior doctors? A Delphi study of consultant physicians’ views. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1992;26:36–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayou R, Bryant B. Psychiatry of whiplash neck injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:441–448. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carstensen TB, Frostholm L, Oernboel E, Kongsted A, Kasch H, Jensen TS, Fink P. Post-trauma ratings of pre-collision pain and psychological distress predict poor outcome following acute whiplash trauma: a 12-month follow-up study. Pain. 2008;139:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]