Introduction

The authors describe a rare case of a 6-year-old boy with inappropriate surgical treatment of spinal echinococcus granulosus by thoracotomy, vertebral resection, multiple laminectomies, and instrumented fusion. This treatment resulted in reoccurrence of the hydatid cyst, paraplegia, and severe kyphoscoliosis.

The authors should be commended for taking on this challenge, which is rarely seen by even the most experienced spine surgeons. We should all learn lessons from this case, and several points stood out as I read the manuscript, which was well organized, illustrated, and referenced by the authors.

Lesson 1

Pediatric patients are prone to developing spine deformities especially kyphosis after multiple laminectomies and should have the procedure combined with appropriate arthrodesis and instrumentation [1, 2]. Most spinal infections can be safely instrumented, and surgeons should not shy away from applying rigid spinal fixation devices in the process of radical resections and laminectomies in the presence of infection [3, 4].

Lesson 2

Surgeons should be very familiar with the hydatid cyst disease when it affects the spine. The peri-operative medical management, complications, and intra-operative care needed to avoid premature rupture of the cyst are well described by the authors. In this case, the risk of cyst rupture and anaphylaxis was weighed against the impending paralysis and the authors chose to surgically intervene successfully.

Lesson 3

Predominant kyphotic deformities with the pathology mostly posterior based should not be approached with a formal thoracotomy procedure. A costotransversectomy approach will provide the needed three-column exposure of the posterior elements, spinal cord, and anterior vertebral structures while allowing concomitant posterior stabilization. This technique has been shown to be the most effective approach for congenital, post TB, post-traumatic, and other hyperkyphotic gibbus deformities in pediatric and adult patients [5–7].

Lesson 4

Undertaking the posterior vertebral column resection requires experience and technical knowledge of the critical steps needed to execute a successful operation. These include temporary stabilization with a rod and pedicle screws, intra-operative spinal cord monitoring, and ability to work around the spinal cord without traumatizing the neural elements.

Using a high speed burr will lessen the vibratory pounding with osteotomies. Maintaining adequate hemodynamics with mean pressure in the 70’s and 80’s is sometimes needed to effect good cord perfusion with motor evoked potentials.

Lesson 5

One should also pay due attention to overzealous correction and shortening of the cord to avoid excessive redundancy and buckling of the cord. This can best be done by visual inspection and placement of anterior cages long enough to maintain the proper cord length. I would personally perform sequential rod exchanges and gradual straightening of each rod as it is removed and replaced. This keeps one rod in at all times. At the end, when I see the correction and cord length is acceptable, I will then place the cage, compress against the cage, and place bone graft around it.

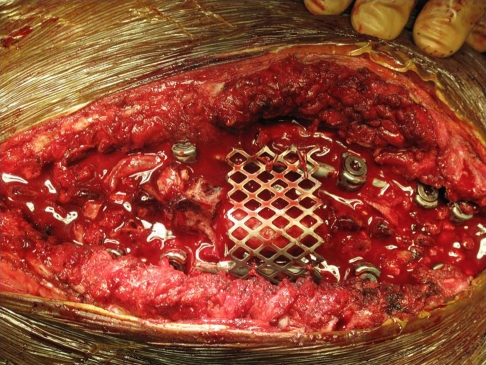

It is impossible at times to close the paraspinal muscle and soft tissue over the exposed dura. In such a case, a half split cylindrical mesh cage can be placed over the dura and sewed to the rod. The neural element will then be protected from tightly closed soft tissue structures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative image of a half split titanium mesh cage placed over exposed dural and spinal rod

The aforementioned lessons were greatly applied in this report and all readers will be well served by adhering to these principles.

References

- 1.Lonstein JE. Post-laminectomy kyphosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;128:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonge T, Slullitel H, Dubousset J, Miladi L, Wicart P, Illés T. Late-onset spinal deformities in children treated by laminectomy and radiation therapy for malignant tumours. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(8):765–771. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0778-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ha K-Y, Chung Y-G, Ryoo S-J, et al. Adherence and biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis on various spinal implants. Spine. 2005;30:38–43. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154674.16708.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oga M, Arizono T, et al. Evaluation of the risk of instrumentation as a foreign body in spinal tuberculosis: clinical and biologic study. Spine. 1993;18(13):1890–1894. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawahara N, Tomita K, et al. Closing–opening wedge osteotomy to correct angular kyphotic deformity by a single posterior approach. Spine. 2001;26:391–402. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajasekaran S, Kamath V, Shetty AP. Single-stage closing-opening wedge osteotomy of spine to correct severe post-tubercular kyphotic deformities of the spine: a 3-year follow-up of 17 patients. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(4):583–592. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenke LG, O’Leary PT, Bridwell KH, Sides BA, Koester LA, Blanke KM. Posterior vertebral column resection for severe pediatric deformity: minimum two-year follow-up of thirty-five consecutive patients. Spine. 2009;34(20):2213–2221. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b53cba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]