Abstract

Background/objectives. Symptoms suggestive of cardiac arrhythmias are a challenge to the diagnosis. Physical examination and a 12-lead ECG are of limited value, as rhythm disturbances are frequently of a paroxysmal nature. New technologies facilitate a more accurate diagnosis. The objective of this study was to review the medical literature in an effort to define a guide to rational diagnostic testing.

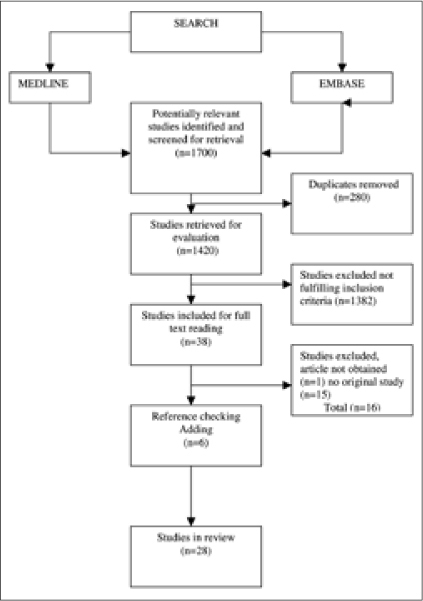

Methods. Primary studies on the use of a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of palpitations were searched in MEDLINE, and EMBASE with an additional reference check.

Results. Two types of studies were found: descriptive and experimental studies, which compared the yield of two or more devices or diagnostic strategies. Holter monitors seemed to have less diagnostic yield (33 to 35%) than event recorders. Automatically triggered recorders detect more arrhythmias (72 to 80%) than patient-triggered devices (17 to 75%). Implantable devices are used for prolonged monitoring periods in patients with infrequent symptoms or unexplained syncope.

Conclusion. The choice of the device depends on the characteristics of the symptoms and the patient. Due to methodological shortcomings of the included studies no evidence-based diagnostic strategy can be proposed. (Neth Heart J 2010;18:543–51.)

Keywords: General Practice, Event Recorder, Palpitations, Arrhythmias, Cardiology

Physicians commonly face patients with symptoms suggestive of cardiac arrhythmias, such as palpitations. However, as the majority of patients do not experience symptoms during consultation and medical history and physical examination are usually inconclusive, diagnostic evaluation is difficult and further diagnostic tests are often indicated. An ECG during symptoms is considered to be the reference standard, but obtaining a symptomatic standard ECG is often not possible.1 Increased emphasis on outpatient diagnosis and recent technical developments have created techniques that facilitate obtaining a symptomatic ECG in an ambulant patient.

A systematic literature search was performed to analyse the available monitoring techniques to diagnose patients with symptoms of palpitations. Based on this research and clinical reasoning we define a guide to rational diagnostic testing in these patients.

Methods

Search strategy

We performed a literature search, using MEDLINE (01/1966-03/2007) and EMBASE (01/1988-03/2007). The complete search strategy is available upon request from the corresponding author. Searches were limited to original studies in humans. We excluded letters and editorials. Languages other than German, French, English, Dutch or Italian were excluded.

Inclusion of studies

The first selection was on title and abstract. The article had to describe an original study on the use of a diagnostic tool, other than a standard ECG in the evaluation of adult outpatients with complaints of palpitations. Duplicates and articles without an abstract were removed. The search was supplemented by reference checking for any missing studies. Although we planned to include only prospective or transversal studies with a clear reference standard this did not prove to be feasible, so we included all original studies on the use of new technology, irrespective of study design.

Two authors (EH, HvW) independently assessed the methodology of the included studies, using the appropriate instruments and extracted data.2 In case of any disagreement, consensus was reached after extensive discussion.

Endpoints

In a true diagnostic study the results of an index test are compared with the results of a reference test. However, when studying the results of new technologies that are supposed to be more sensitive and/or specific than existing ones, such study designs are not feasible.3 Therefore evaluation of such new technologies should focus on the clinical consequences.4 Thus adequate endpoints of diagnostic studies in case of palpitations, in which a new technology is studied, can be ‘detected arrhythmias’ (with or without clinical consequences) or ‘explained symptoms’ (with or without consequences in management). These outcomes are different, as a detected arrhythmia does not necessarily explain the symptoms for which patients seek medical help, and not all arrhythmias are clinically relevant. On the other hand relevant arrhythmias do not always produce symptoms. Therefore we report both endpoints, detected arrhythmias as well as explained episodes, whenever possible. We use the term ‘relevant arrhythmia’ when treatment and/or further clinical evaluation is needed. We considered an arrhythmia relevant in case of (paroxysmal) atrial fibrillation (PAF), atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia, other supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), ventricular tachycardia or escape rhythm.

We intended to perform a meta-analysis, but as the data could not be combined, studies are reported in a narrative form.

Results

The results of the search and subsequent assessment of identified studies are summarised in figure 1. Our search yielded 1700 articles. After reading the title and abstract, 38 articles were labelled potentially relevant.

Four reviews were excluded because these reviews were not systematic and included no original data. One reference could not be retrieved, even after mailing the author, 11 articles did not describe a diagnostic method or included patients without palpitations. Reference checking yielded a total of six additional relevant articles. Finally 28 studies were available for analysis (figure 1). Performing meta-analysis did not prove to be possible, either due to clinical heterogeneity or due to methodological heterogeneity.

Available technologies

Our search yielded six different diagnostic devices, which are currently available to register an ECG while the patient is ambulant (table 1).

Holter monitoring continuously records a 12-lead ECG over a 24 to 48 hour period. Recently even up to 72 hours. Since 1960, it has been the first choice for additional workup in detecting and quantification of suspected arrhythmias. To link ECG changes to occurring symptoms patients must keep up a diary during the monitoring period.

External event recorders without loop, also known as trans telephonic monitoring (TTM) are a form of non-continuous ambulatory recordings. After activation by the patient an ECG is recorded. The recorded event must be directly transmitted by telephone to a receiving centre.

Event recorders with looping memory (continuous event recorders: CER) make a continuous one-lead recording, but the rhythm strip will only be saved when a patient activates the device. Most devices can be programmed to save pre-activation and post-activation rhythm strips. Several designs are available, for example, with electrodes attached to the chest, with a device around the wrist or a handheld credit card design.

Autotriggered event monitors with looping memory (At-CER) automatically recognise (pre-specified) high or low heart rates and were introduced a few years ago. Several types of devices are now available,5 R-test evolution (RTE) performs a continuous ECG analysis combined with an automatic storage of abnormal events detected in a 20-minute solid-state memory with autonomy of up to seven days. In addition, the patient can trigger a recording in case of symptoms. These functions can run simultaneously. The most recent advancement in ambulatory arrhythmia monitoring is mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry.6 Patients wear three chest leads attached to a portable sensor that continuously detects asymptomatic pre-specified arrhythmias and transmits the ECG data in real-time to a pocket-sized monitor at the patient’s home. If the algorithms in the monitor detect an abnormal heartbeat, the monitor automatically transmits the patient’s ECG data to the monitoring centre using wireless communications. Also away from home the device communicates continuously with the service centre.

Implantable autotriggered loop recorders (ILR) require a minor invasive procedure. Recording possibilities are the same as with nonimplantable autotriggered loop recorders.7 Because external electrodes are not necessary the ILR can be used by patients for a long period of time (12 to 24 months). Currently, remote transmission capabilities are not available.

Pacemakers and cardiodefibrillators are implanted primarily to pace and/or shock the heart. These devices can be programmed to detect and store rhythm abnormalities as well and send data to a remote receiving facility.8

Table 1.

Types of devices for specific patient groups and their complaints of palpitations.

| Device | Patient activated | Automatic activated | Memory | Duration | Leads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holter monitor | X | 24–48 hours | Variable till 12 leads | ||

| Event recorder no-loop (TTM) | X | Unlimited | Variable | ||

| Event recorder with loop (CER) | X | X | Unlimited | 2–3 leads | |

| Autotriggered event recorder (R-test evolution, MCOT) | X | X | X | 7 days | 1–3 leads |

| Implantable loop recorder | X | X | 12–24 months | 2 leads |

TTM=trans-telephonic monitoring, CER=continuous event recorder, MCOT=mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry.

The yield of available devices

The search yielded two types of studies. Descriptive (prospective and historical) cohort studies, describing the yield of a device in terms of explained episodes or diagnosed arrhythmias. The second type are experimental studies, which compare the yield of two or more devices or diagnostic strategies in the same patient or in randomised groups of patients.

For all included studies we report on the aim, setting, inclusion criteria, completeness of followup, sample size documented, statistical analyses described and outcomes. In case of a randomised trial we used the quality criteria as mentioned by Jadad: 1) randomisation of participants; 2) blinding of patients, caregivers and those assessing outcome; and 3) full description of withdrawals and dropouts.9

Descriptive studies

Of the 28 studies 12 were simple descriptive studies, which described the yield of Holter monitoring and event recording with and without loop in a group of patients. The study device serves as its own reference test and the outcomes are described in terms of proportions of patients in which a relevant or less relevant arrhythmia is diagnosed or changes in medical management have been implemented. These studies are described in table 2. The patients included in these studies are not comparable and many studies described inclusion criteria superficially; most patients were in tertiary care with a variable amount of (sometimes previously known) cardiac pathology. Event recording with loop seems to generate most diagnoses, but comparison of the results of these studies is methodologically not possible and would probably lead to false conclusions. Recommendations have to be based on studies which compared the yield of two or more devices in the same or in randomised groups of patients.10–21

Comparative studies

These studies have in common that the outcomes of the studied devices are compared with another diagnostic test. As in descriptive studies, combining of results was methodologically not possible in these studies because of the diversity of the studied populations and the variation in tested devices. Most patients were in tertiary care with a variable amount of (sometimes previously known) cardiac pathology. Many studies described inclusion criteria superficially, although in more recent studies this is done more appropriately following a protocol (table 3).

Table 2.

Descriptive studies.

| Source | Study design/Aim | Inclusion criteria | Setting/Gender/Mean age | Instrument/Registration time | Dropout | Outcome and diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holter | Erikson 1980 | Retrospective, descriptive Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, dizziness, falls breathlessness, chest pain, syncope | Tertiary care n=150 57% males 59 years | Portable onechannel cassette tape recorder | ND | 29% relevant diagnoses 46% management change |

| Rana 1989 | Retrospective, descriptive Diagnostic yield, management | Palpitations, dizziness, falls breathlessness, chest pain, syncope | Geriatric OPs n=252 Gender 60–92 years | Reynolds onechannel ECG recorder 24 hours | ND | 12% relevant diagnoses 10% change in management | |

| McClennen 2000 | Retrospective, descriptive Diagnostic yield and cost | Palpitations, presyncope, cerebral ischaemia, AF evaluation | Tertiary care n=164 74% males 59 years | 2×24 h Holter | ND | Day 1: 19% relevant diagnoses Day 2: 3% relevant diagnoses | |

| Event recorder no loop | Safe 1990 | Prospective descriptive Diagnostic yield | 73 palpitations, 6 dizziness, 3 chest pain and palpitations Standard ECG not diagnostic | Tertiary care n=82 62% males 17–76 years | CER, no loop, (stores 32 sec) 1 month | 1 patient | 23% diagnoses 13% relevant diagnoses |

| Assayag 1992 | Retrospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations 41% cardiopathology | Tertiary care n=1287 37% males 52 years | CER no loop | 196 incomplete files | 42% diagnoses | |

| Schuchert 2002 | Prospective, descriptive Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, Holter neg 43% cardiopathology | OPs n=55 38% males 46 years | One-channel ECG (handheld), 6 weeks | ND | 32% relevant diagnoses | |

| Shanit 1996 | Prospective, descriptive Diagnostic yield | Chest pain, arrhythmia, hypertension, reassurance | OP n=2563 ?? ?? | 12 lead ECG (handheld) | ND | 26% relevant diagnoses | |

| Event recorder with memory loop | Summerton 2000 | Prospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations | Primary care n=139 33% male 45 years | Rhythm card (handheld), no pre event memory 2 weeks | ND | 30% diagnoses, 19% relevant diagnoses |

| Fogel 1997 | Prospective Diagnostic yield, cost | Palpitations, pre-syncope 25% cardiopathology | OPs n=184 31% males 44 years | Wrist CER 4 weeks | ND | 66% patients with palpitations, 43% relevant diagnoses Most costeffective with palpitations | |

| Zimetbaum 1998 | Prospective Diagnostic yield, cost, diagnoses timing | Palpitations | OPs n=112 26% males 52 years | CER 4 weeks | 7 patients, incomplete files | 84% diagnoses <2weeks, 36% relevant diagnoses 2 weeks costeffective | |

| Brown 1987 | Retrospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations dizziness, syncope, abnormal Holter, symptoms after treatment 39% cardio-pathology | OPs n=106 ?? 58 years | CER 3 weeks | 6 patients, incomplete files | 66% diagnoses, 7% relevant diagnoses | |

| Wu Chih Cheng 2003 | Retrospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, pre-syncope, chest pain, dyspnoea 50% cardiopathology | Tertiary care n=660 47% males 53 years | CER 30 days | ND | 64% diagnoses Palpitation group 66% diagnoses |

ND=not described. OP=outpatients, AF=atrial fibrillation, CER=continuous event recorder

CER vs. Holter monitoring.

In six studies the CER is compared with Holter monitoring (24 to 48 hours). Registration time with the CER varied from one week to six months. The studied populations consisted of 50 to 100 patients, one study described 310 patients. The patient populations consisted of primary and secondary care patient groups. From the latter, about 41% of the patients had documented structural heart disease. Outcomes were described in terms of proportions of patients in whom a relevant or less relevant arrhythmia was diagnosed or in whom changes in medical management were implemented. With the CER, a diagnosis was established in a range 21 to 62% of the studied patients, compared with a maximum of 30% with Holter monitoring. The CER was better at excluding arrhythmias during symptoms than the Holter monitor (34 and 2%, respectively).22–27

CER vs. ECG monitoring,

Records of 91 patients were reviewed. Within 30 days the CER was diagnostic in 37% of patients, while a 12-lead ECG was diagnostic in 10% of patients.28

CER vs. usual GP care

In a randomised trial the diagnostic yield of CER versus usual care in general practice was compared. Within one month, 83% of the patients recorded an episode. The CER diagnosed 67% of patients with a cardiac arrhythmia, while the GPs diagnosed 27% of patients with a cardiac arrhythmia (p<0.05) after six months.29

AT-CER (R-test evolution) vs. patient-triggered mode of the AT-CER

In three studies with 262 (range 65 to 101) patients, the automatically triggered mode was compared with the patient-triggered mode of the device. In two of these studies, patients had negative 24-hour Holter monitoring. All studies included selected patients with a history of pre-existent cardiac pathology. Registration time varied from 77 to 103 hours. With both modes of the device, in more than 80% of the patients (range 75 to 88%) a diagnosis could be established. When compared with the patient-triggered mode, in all three studies the automatically triggered mode of the device found an additional amount of relevant diagnoses (range 11 to 17%).5,30,31

In a fourth larger study by Reifel et al.,32 with 1800 patients, the AT-CER was compared with the traditional CER and 24-hour Holter monitoring. Each group consisted of 600 patients. The patient group who used the AT-CER had a diagnostic yield of 71 vs. 27% with the patient-triggered CER and 6% diagnosis with 24-hour Holter monitoring. Recording time of CER and AT-CER was one month.

CER vs. AT-CER (by MCOT)

In a randomised trial the diagnostic yield of CER versus AT-CER (by MCOT) was tested during 30 days in 266 patients. Previous Holter monitoring was non-diagnostic. With the autotriggered mode, an arrhythmia was detected in 41% of the patients, compared with 15% in the CER group.33

Table 3.

Comparative studies.

| Source | Study design/Aim | Inclusion criteria | Setting/Gender/Mean age | Blinding observer | Dropout | Instrument/Registration time | Proportion patients with diagnoses* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CER vs Holter | Grodman 1979 | Prospective, comparative Diagnostic yield | Palpitations | - OPs - n=59 - 45% males - 50 years |

ND | 19 failed transmitting, 4 failed for technical reasons | CER (cardiobeeper) vs Holter, simultaneously 1 week | Holter 3 pts, CER 3 pts, Holter and CER together 9 pts |

| Visser 1984 | Prospective, comparative Diagnostic yield | Palpitations | - OPs - n=50 - 34% males - 44 years |

ND | 3 pts, ND | CER (cardiobeeper) vs Holter, same patient group, max 6 wks | CER 62%, Holter 12% | |

| Scalvini 2005 | Prospective, randomised, | Palpitations 41% cardiopathology | - Tertiary care -n=310 - 24% males - 52 years |

No | ND | CER vs Holter at same time 7 days | CER 52%, Holter 48% | |

| Kus 1995 | Prospective cross-over Diagnostic yield | Palpitations | - Tertiary care - n=100 - 34% males - 55 years |

ND | 3 pts, technical reasons | First Holter then CER max 25 days | CER 21%, Holter 30% Exclusion diagnoses CER 34% vs Holter 2% | |

| Kinlay 1996 | Prospective randomised, crossover Diagnostic yield | Palpitations | - OPs - n=43 -12% males - 45 years |

Blinded for data, results | 2 pts, non compliance | Post-event monitor (handheld) vs 48-h Holter 3 months | CER 67%*, Holter 30%* | |

| Klootwijk 1986 | Prospective cohort Diagnostic yield | Palpitations 24-h Holter twice neg. | - OPs - n=100 - ?? - ?? |

NA | ND | First 2 * Holter, then CER (handheld) Max 6 months | 2* negative Holter, CER 48% | |

| CER vs ECG | Wu Jenny 1995 | Retrospective Diagnostic yield, costs | Palpitations pre-syncope, syncope, dizziness | - OPs - n=91 - 94% males - 64 years |

NA | 5 pts from TTM; 5 incomplete files | First Ambulatory ECG than CER 30 days | CER 37%, ECG 10% |

| CER vs GP care | Hoefman 2005 | Prospective, randomised, 1:1 Diagnostic yield | Palpitations and/or dizziness | - GP -n=244 - 26% males - 50 years |

No blinding | 1 pt, non-compliance | CER/usual care GP, 30 days | CER 67%, usual care 27% significant* |

| Roche 2002 | Prospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations and neg. 24-h Holter. 40% cardio-pathology | - OPs - n=65 - 69% males - 63 years |

NA | ND | R-test evolution (RTE) manually and automatically triggered 77 hours | AT-CER 80%, pt-triggered 67% | |

| Martinez 2004 | Prospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, dizzy, syncope, neg Holter 11% cardio-pathology | - OPs - n=96 - 52% males - 37 years |

NA | ND | R-test evolution (RTE) manually and automatically triggered 5.2 days | CER mode 22%, additional diagnoses in automatic recordings 17% | |

| Balmelli 2003 | Prospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, dizziness, syncope 52% cardio-pathology | - OPs -n=101 - 60% males - 54 years |

Cardio. blinded for results | ND | R-test evolution (RTE) manually and automatically triggered 7 days | Pt-triggered 37%, autotriggered 63%, additional diagnoses in asymptomatic pts 61% | |

| CER vs AT-CER | Reiffel 2005 | Retrospective 1:1:1 Diagnostic yield | Unknown | - Tertiary care -n=1800 - 40% males |

NA | ND | HM/CER/AT-CER 30 days | AT-CER 71%, CER 27% HM 6% |

| Rothman 2007 | Prospective randomised 1:1 Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, cardio-pathology: MCOT 84%, CER 62% | - OPs -n=266 - 34% males - 56 years |

Double-blinded to history, randomisation | MCOT 13 pts, CER 7 pts technical reasons, non-compliance | AT-CER (MCOT), CER 30 days | MCOT 41% CER 15%* | |

| Olson 2007 | Retrospective; palpitation n=76 syncope n=17, evaluation therapy n=19 Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, (pre)syncope, therapy evaluation 33% cardio-pathology | - OPs -n=122 - 43% males - 58 years |

NA | ND | MCOT, automatic mode, patient-triggered mode Duration ?? | Palpitation group: 73% symptomatic diagnoses. in 11% asymptomatic diagnoses, in previous diagnosed group 47% | |

| CER vs ILR | Ng 2003 | Retrospective Diagnostic yield | Palpitations, (pre)syncope | - Tertiary care - n=50 - 44% males - 54 years |

NA | ND | ILR (Reveal plus) automatic and Pt triggered 12 months | Autotriggered 10%, pttriggered 16%, inappropriate activation autotriggered mode |

| Giada 2007 | Prospective randomised 1:1 Diagnostic yield | Palpitations initial negative evaluation | - OPs - n=50 - 34% males - 47 years |

No blinding | ND | Conventional group: Holter, CER, EP vs ILR 12 months | Conventional strategy group 21%, ILR 73%* |

* p<0.05. NA=not applicable, ND=not described, GP=general practice, MCOT=mobile cardiac output telemetry, CER=continuous event recorder, ILR=implantable loop recorder, TTM=trans-telephonic monitoring, EP=electrophysiological testing, pts=patients.

Diagnostic yield in automatic vs. patient-triggered mode using an MCOT-CER

Olson et al.34 reviewed records of 122 patients evaluated with an MCOT AT-CER. An arrhythmia was recorded in 73% of the patients with new-onset palpitations. In 11% of the patients, an automatic registration of an asymptomatic arrhythmia occurred.

In patients with previously diagnosed arrhythmias, an arrhythmia was documented in 47%. Documentation of these arrhythmias was automatically triggered in 63%, and 41% of the arrhythmias remained asymptomatic.

Automatic implantable loop recording (ILR) versus patient-triggered recordings

Ng et al.35 compared the diagnostic yield of patienttriggered vs. automatic activation mode of the ILR in 50 patients. Using patient-triggered mode, arrhythmias occurring simultaneously with symptoms were registered in 16% of the patients. No relevant arrhythmias were detected by auto-activation only. The effectiveness of auto-activation to detect arrhythmia was reduced due to a high rate of inappropriate activation (83%), due to under- and over-sensing of the device. Withdrawals were not described.

ILR versus conventional strategy

Giada et al.36 studied 50 patients in whom initial cardiological evaluation did not yield a diagnosis. The diagnostic yield of the ILR was randomly compared with conventional strategy (24-hour Holter recording, a four-week period of CER, and/ or electrophysiological testing if the previous two strategies yielded negative results). A diagnosis was obtained in five patients (21%) of the conventional strategy group: two patients were diagnosed with a CER and three patients were diagnosed with electrophysiological studies. With the ILR, arrhythmias were documented within one year in 19 patients (73%).

Discussion

We searched for studies evaluating the clinical utility of available technologies to diagnose palpitations and found six different groups of devices with different application characteristics. Twenty-eight studies were identified. Most of these studies described the yield of a specific device in a small group and of mostly highly selected patients. Therefore many of the studies are not very informative. Comparative studies provided more information, but most studies suffered from methodological shortcomings. Advice on which device to use for which problem or for which patient therefore is not straightforward and mainly based on the frequency of symptoms and the consideration of whether or not patients feel palpitations. When diagnosing palpitations and a standard ECG does not provide an explanation of the symptoms, Holter monitoring can be used when a patient has very frequent (daily) symptoms, an event recorder (auto- or patient-triggered) can be used when a patient has weekly symptoms. In symptomatic patients, patient-activated devices are preferred above autotriggered devices as the relation between symptoms and ECG abnormalities is clear. Autotriggered devices may more often detect an abnormality of the rhythm, but as direct linkage to perceived symptoms is missing, these devices are less well capable of explaining symptomatic episodes, unless used in the patient-triggered mode. Besides, the patient triggering can be used to demonstrate that the rhythm is not abnormal during symptoms, thus providing reassurance to anxious patients (and to their physicians because of exclusion of relevant arrhythmias). When a patient cannot operate the device (comorbidity, old age) an autotriggered recorder or MCOT can be used. A second reason for an autotriggered device is palpitation of an irregular pulse without the patient feeling any irregularity, in case of possible PAF.

Limitations

Cardiac monitoring devices are described in the literature under different names. Although we tried to perform a maximally sensitive search strategy, some studies may have been missed. Many of the identified studies are of weak methodology and comparison of the results of the studies is hazardous. The lack of true diagnostic studies is not just caused by weak methodology, however, but also by the lack of an accepted reference standard. Obtaining a registration of a rhythm that shows abnormalities might be considered to be a reference standard, but linking of such an abnormality to symptoms is not without uncertainties and sometimes even wrong.

CERs come in a variety of models. As the design of the devices may influence capability and readiness of recording arrhythmias, this may in part explain the observed differences in diagnostic yield.

Conclusion

Recent developments in ambulatory ECG recording offer the opportunity to diagnose most symptoms of palpitations, also in ambulant patients and in primary care. The choice of the device depends on frequency and character of the symptoms and is not evidence-based. Infrequent paroxysmal asymptomatic arrhythmias can best be documented using an AT-CER or an ILR for an extended period. In primary care, patient-triggered event recording has the advantage of a direct link between arrhythmias and symptoms, which makes it possible to not only diagnose relevant arrhythmias, but also demonstrate harmless rhythm disturbances (as sinus tachycardia) as an explanation for symptoms to the patient. When asymptomatic episodes are suspected or patients are incapable of operating the device an autotriggered device is preferred.

Future research should focus on comparison of different devices in homogenous patient groups. The outcome should be reported in two ways: explained episodes and clinically relevant arrhythmia.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Dutch College for Health Insurance (CVZ) and by Agis Health Insurances.

*Authors contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Zwietering PJ, Knottnerus JA, Rinkens PE, Kleijne MA, Gorgels AP. Arrhythmias in general practice: diagnostic value of patient characteristics, medical history and symptoms. Fam Pract. 1998;15:343–353. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Fam Pract. 2004;21:4–10. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Coomarasamy A, Khan KS, Bossuyt PMM. Evaluation of diagnostic tests when there is no gold standard. A review of methods. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:iii,iv–51. doi: 10.3310/hta11500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasziou P, Irwig L, Deeks JJ. When should a new test become the current reference standard? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:816–821. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez T, Sztajzel J. Utility of event loop recorders for the management of arrhythmias in young ambulatory patients. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:495–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi AK, Kowey PR, Prystowsky EN, Benditt DG, Cannom DS, Pratt CM, et al. First experience with a Mobile Cardiac Outpatient Telemetry (MCOT) system for the diagnosis and management of cardiac arrhythmia. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:878–881. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krahn AD, Klein GJ, Skanes AC, Yee R. Insertable loop recorder use for detection of intermittent arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:657–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plummer CJ, Henderson S, Gardener L, McComb JM. The use of permanent pacemakers in the detection of cardiac arrhythmias. Europace. 2001;3:229–232. doi: 10.1053/eupc.2001.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson L, Pahlm O. The clinical impact of long-term ECG recording. A retrospective study of 150 patients. Acta Medica Scand. 1980;208:355–358. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1980.tb01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rana MZ, Dunstan EJ, Allen SC. Ambulatory electrocardiography in elderly: an audit. Br J Clin Pract. 1989;43:341–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClennen S, Zimetbaum PJ, Ho KKL, Goldberger AL. Holtermonitoring: are two days better than one? Am J Cardiol. 2000;869:562–564. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safe AF, Maxwell RT. Transtelephonic electrocardiographic monitoring for detection and treatment of cardiac arrhythmia. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:110–112. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.772.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assayag P, Chailley O, Lehner JP, Brochet E, Demange J, Rezvani Y, et al. Contribution of sequential voluntary ambulatory monitoring in the diagnosis of arhythmia. A multicenter study of 1287 symtomatic patients. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1992;85:281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuchert A, Behrens G, Meinertz T. Evaluation of infrequent episodes of palpitations with a patient-activated hand-held electrocardiograph. Z Kardiol. 2002;91:62–67. doi: 10.1007/s392-002-8373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanit D, Cheng A, Greenbaum RA. Telecardiology: supporting the decisionmaking process in general practice. J Telemed Telecare. 1996;2:7–13. doi: 10.1258/1357633961929105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Summerton N, Mann S, Rigby A, Petkar S, Dhawan J. New-onset palpitations in general practice: assesing the discriminant value of items within the clinical history. Fam Pract. 2001;18:383–392. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fogel RI, Evans JJ, Prystowsky EN. Utility and cost of event recorders in the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, and syncope. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:207–208. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimetbaum PJ, Kim KY, Josephson ME, Goldberger AL, Cohen DJ. Diagnostic yield and optimal duration of continuousloop event monitoring for the diagnosis of palpitations. A costeffectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:890–895. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-11-199806010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown AP, Dawkins KD, Davies JG. Detection of arrhythmias: use of a patient-activated ambulatory electrocardiogram device with a solid-state memory loop. Br Heart J. 1987;58:251–253. doi: 10.1136/hrt.58.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C-C, Hsieh M-H, Tai C-T, Chiang C-E, Yu W-C, Lin Y-K, et al. Utility of patient-activated cardiac event recorders in the detection of cardiac arrhythmias. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiol. 2003;8:117–120. doi: 10.1023/A:1023604816368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grodman RS, Capone RJ, Most AS. Arrhythmia surveillance by transtelephonic monitoring: comparison with Holter monitoring in symptomatic ambulatory patients. Am Heart J. 1979;98:459–464. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(79)90251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Visser J, Schuilenburg RM. Trans-telephonic ECG monitoring in the diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias: A comparison with Holter electrocardiography. Ned Tijdschrift Geneeskund. 1984;128:397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scalvini S, Zanelli E, Martinelli G, Baratti D, Giordano A, Glisenti F. Cardiac event recording yields more diagnoses than 24-hour Holter monitoring in patients with palpitations. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11(Suppl 1):14–16. doi: 10.1258/1357633054461930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kus T, Nadeau R, Costi P, Molin F, Primeau R. Comparison of the diagnostic yield of Holter versus transtelephonic monitoring. Can J Cardiol. 1995;11:891–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinlay S, Leitch JW, Neil A, Chapman BL, Hardy DB, Fletcher PJ. Cardiac event recorders yield more diagnoses and are more cost-effective than 48-hour Holter monitoring in patients with palpitations. A controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(1 Pt 1):16–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_part_1-199601010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klootwijk P, Leenders CM, Roelandt J. Usefulness of transtelephonic documentation of the electrocardiogram during sporadic symptoms suggestive of cardiac arrhythmias. Int J Cardiol. 1986;13:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(86)90140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J, Kessler DK, Chakko S, Kessler KM. A cost-effectiveness strategy for transtelephonic arrhythmia monitoring. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:184–185. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)80075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoefman E, van Weert HC, Reitsma JB, Koster RW, Bindels PJ. Diagnostic yield of patient-activated loop recorders for detecting heart rhythm abnormalities in general practice: a randomised clinical trial. Fam Pract. 2005;22:478–484. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roche F, Gaspoz JM, Da CA, Isaaz K, Duverney D, Pichot V, et al. Frequent and prolonged asymptomatic episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation revealed by automatic long-term event recorders in patients with a negative 24-hour Holter. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1587–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balmelli N, Naegeli B, Bertel O. Diagnostic yield of automatic and patient-triggered ambulatory cardiac event recording in the evaluation of patients with palpitations, dizziness, or syncope. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26:173–176. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960260405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiffel JA, Schwarzberg R, Murry M. Comparison of autotriggered memory loop recorders versus standard loop recorders versus 24-hour holter monitors for arrhythmia detection. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1055–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothman SA, Laughlin JC, Seltzer J, Walia JS, Baman RI, Siouffi SY, et al. The diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias: a prospective multi-center randomized study comparing mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry versus standard loop event monitoring. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olson JA, Fouts AM, Padanilam BJ, Prystowsky EN. Utility of mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry for the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, syncope, and the assessment of therapy efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:473–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng E, Stafford PJ, Ng GA. Arrhythmia detection by patient and auto-activation in implantable loop recorders. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2004;10:147–152. doi: 10.1023/B:JICE.0000019268.95018.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giada F, Gulizia M, Francese M, Croci F, Santangelo L, Santomauro M, et al. Recurrent unexplained palpitations (RUP) study comparison of implantable loop recorder versus conventional diagnostic strategy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1951–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]