Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising new modality that utilizes the combination of a photosensitizing chemical and visible light for the management of various solid malignancies, including gastrointestinal (GI) cancer. PDT has some advantages over chemotherapy in terms of its greater safety and lower toxicity in the treatment of malignant lesions. However, PDT has not been used widely for treating upper GI cancer due to its relatively low cost-effectiveness and anatomical characteristics of the GI system. Nevertheless, PDT may be an effective alternative therapy for early upper-GI cancer patients who are at a high risk of curative surgical resection or systemic chemotherapy. In some clinical studies, PDT for various upper GI cancer showed positiveresults. To improve the efficacy of PDT for upper GI cancer, development of photosensitezer and light delivery system is needed.

Keywords: Photodynamic therapy, Photosensitizer, Upper-gastrointestinal cancer

INTRODUCTION

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) utilizes the unique characteristics of photosensitizer which accumulates in tumor and uses light energy to destroy malignant neoplasm. It was first adopted in treatment of esophageal malignancies since early 1980s and is now increasingly used in treatment of gastric cancer, biliary cancer and colon cancer.1 The PDT accurately delivers light energy to the target lesion which enables selective tissue destruction and minimizes adjacent normal tissue damage.2 Therefore it is possible to maintain gastrointestinal system's mechanical function and is suitable for repeated treatment of small lesions of immunocompromised patients.3 Since the advent of this novel treatment modality, PDT has yet to prove its superiority to other treatment methods and development of newer photosensitizer and improvement of light delivery system remains an unsolved, ongoing problem. Nevertheless, the PDT remains a useful and noteworthy treatment modality because of the recent increasing needs for a minimal invasive treatment method. In this review, we will discuss the principles and mechanisms of PDT and its clinical applications, especially on esophageal cancer, Barrett's esophagus, and gastric cancer.

PRINCIPLES AND MECHANISMS

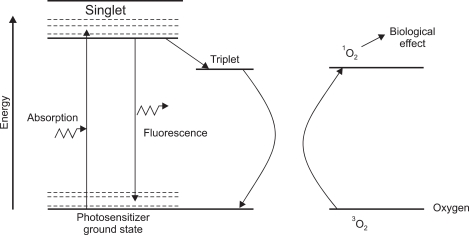

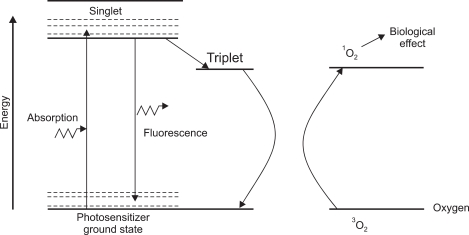

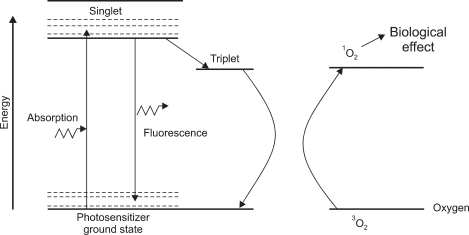

PDT is defined as the therapeutic use of photosensitizers which are activated by light.4 The three main steps for PDT include injection of photosensitizer, activation of photosensitizer by endoscopy guided red light application, and cell death by production of active oxygen.5 Fig. 1 is a typical energy level diagram for photosensitizer activation.6 A photon of light, of an appropriate wave-length, is absorbed by the photosensitizer molecule, raising it from ground state to a short-lived (singlet) excited state. The next step is intersystem crossover in which internal rearrangement to a longer-lived (triplet) state porphyrin takes place (Fig. 2). Finally, the reactive oxygen is produced which provides biological effects (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Energy absorption and excitation: singlet (short-lived) excited-state porphyrin.

Fig. 2.

Intersystem crossover (electron spin conversion): internal rearrangement to a longer-lived (triplet-state) porphyrin.

Fig. 3.

Production of highly active singlet oxygen.

EQUIPMENTS

PTD involves three separate components. The photosensitizer, light source, and light delivery systems. A brief lists of current PDT drugs are given in Table 1.6 Hematoporphyrin derivatives (HPD), the 1st clinical photosensitizer, commercially available as Photoprin is currently widely in use. However, due to its limitation such as instability at room temperature, long skin photosensitivity and weak light absorption at wavelengths above 600 nm, 2nd generation drugs are now undergoing clinical trial. They are benzoporphyrin derivatives, mTHPC, pupurines and chlorin derivatives and ALA.7 Most clinical drugs have optimal activity in 530-700 nm range. In this wavelength range, Laser has been the preferred light source. Ideal source should generate enough light with the correct wavelength, in a convenient, flexible way for delivery to the tissues. For delivery of light, a radially diffusing cylindrical or frontal diffuser or a balloon-diffuser system can be used to adapt the light irradiation to the shape of the target tissue. The balloon-diffuser system has been shown to be successful in centering the rays of radiation and providing a uniform circumferential and predictable light delivery.

Table 1.

Examples of Photodynamic Therapy Drugs

*Currently in clinical trials.

PHOTODYNAMIC THERAPY FOR UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL CANCER

Possible Indications for PDT are obstructing esophageal cancer, superficial esophageal cancer, Barrett's esophagus with HGD, gastric cancer, duodenal/ampullary neoplasm, cholangiocarcinoma/pancreatic cancer, small bowel cancer, colorectal cancer.

In Barrett's esophagus and esophageal cancer, the standard treatment is surgery but it has substantial morbidity and postoperative complications. In shallow, early dysplastic lesions, PDT can be an effective treatment option.8,9

As for early gastric cancer, PDT is technically more difficult and its use has been limited due to stomach's unique geometry like gastric folds, peristalsis, etc. Therefore at the moment, endoscopic submucosal dissection has been a mainstay of the curative treatment but also carries the risk of complications like perforation and bleeding. Although PDT has limitation on deep lesion, it has proved to be effective for the treatment of certain shallow and small-diameter early gastric cancer without disturbing the stomach geometry.10 PDT can also be useful in early, shallow gastric cancer in elderly and immunocompromised patients.

CLINICAL DATA

Table 2 is a summary of reported cases of esophageal cancer treated by PDT showing variable complete remission rate ranging 40% to 100% for early and 91% to 100% for advanced cancer.11 For the treatment of Barrett's esophagus, PDT can be effective in many cases. The reported rate of successful ablation of combined low grade dysplasia or Barrett's esophagus itself ranges from 82% to 100%, and successful ablation rate in high grade dysplasia or cancer was 77% to 91% (Table 3).9,12-16 However, these studies confirmed the feasibility, safety of the PDT, and obtained mixed success as well in terms tumor response. Some report complete histologic response in "advanced" tumors, whereas others report only partial response even in "early" tumors.

Table 2.

Summary of Reported Cases of Esophageal Cancer Treated by Photodynamic Therapy

Table 3.

Summary of Randomized Controlled Trials of Photodynamic Therapy in Barrett's Esophagus

LGD, low grade dysplasia; EC, esophageal cancer; HGD, high grade dysplasia.

Unfortunately the analysis of PDT for gastric cancer is plagued by mixed and varied results with low patient numbers and inadequate follow-up. In several studies in Japan, The largest series by Mimura et al.17 included 27 patients with early gastric cancer: After PDT using photoprin administration two days before procedure, the complete remission rate was 88%, whereas a smaller study including seven patients using same phortsensitizer, showed 100% of complete remission rate. Another study using 2nd generation photosensitizer, the rate of complete remission was 73%.10

During the past four years, PDT was performed 14 patients with gastric cancer in Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea. Study patients included seven patients for curative treatment: six with early gastric cancer and one high grade dysplasia, who were inoperable due to either severe comorbidities or refusal of resection ether by surgery or endoscopic submucosal dissection, and five patients for adjuvant therapy after endoscopic submucosal dissection due to either incomplete resection in two patients and positive margin in three. In the rest 2 patients, PDT was done for palliation of symptoms. PTD was done using photozem, near identical with photofrin, in doze of 2-3 mg/kg, as a photosensitizer. one patient completed therapy after one session and other 13 patients underwent two sessions with average interval of 2 days. Follow-up upper GI endoscopy and tissue biopsies were done at 1, 3, and 6 months after the therapy. The CR rate in curative treatment group was 57% with PDT only and 67% with combination of local therapy. And 60% in the adjuvant therapy group after ESD. In palliative treatment group, although small in number, all showed symptomatic improvement, resulting in a total of 71% of response rate as expected.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, PDT for gastric cancer is one of the treatment options in selected cases. However, how to maximize clinical efficacy is unclear. With the development of light delivery system and new photosensitizer, more energy and high dose of photosensitizer than usual may be the "answer". We also need new trials aimed at improving efficacy.

References

- 1.McCaughan JS, Jr, Guy JT, Hawley P, et al. Hematoporphyrin-derivative and photoradiation therapy of malignant tumors. Lasers Surg Med. 1983;3:199–209. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr H, Dix AJ, Kendall C, Stone N. Review article: the potential role for photodynamic therapy in the management of upper gastrointestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:311–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr H, Tralau CJ, Boulos PB, MacRobert AJ, Tilly R, Bown SG. The contrasting mechanisms of colonic collagen damage between photodynamic therapy and thermal injury. Photochem Photobiol. 1987;46:795–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang KK, Lutzke L, Borkenhagen L, et al. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus: does light still have a role? Endoscopy. 2008;40:1021–1025. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson BC, Patterson MS. The physics, biophysics and technology of photodynamic therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:R61–R109. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/9/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson BC. Photodynamic therapy for cancer: principles. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:393–396. doi: 10.1155/2002/743109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buskard NA, Wilson BC. Introduction to the symposium on photodynamic therapy. Semin Oncol. 1994;21:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossner L, Stolte M, Sroka R, et al. Photodynamic ablation of high-grade dysplasia and early cancer in Barrett's esophagus by means of 5-aminolevulinic acid. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:448–455. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siersema PD. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus: not yet ready for the premier league of endoscopic interventions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ell C, Gossner L, May A, et al. Photodynamic ablation of early cancers of the stomach by means of mTHPC and laser irradiation: preliminary clinical experience. Gut. 1998;43:345–349. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.3.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubba AK. Role of photodynamic therapy in the management of gastrointestinal cancer. Digestion. 1999;60:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000007582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, Davis MF, et al. Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett's oesophagus: a prospective, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2000;47:612–617. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelty CJ, Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, Stephenson TJ, Stoddard CJ, Reed MW. Endoscopic ablation of Barrett's oesophagus: a randomized-controlled trial of photodynamic therapy vs. argon plasma coagulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1289–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hage M, Siersema PD, van Dekken H, et al. 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy versus argon plasma coagulation for ablation of Barrett's oesophagus: a randomised trial. Gut. 2004;53:785–790. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overholt BF, Lightdale CJ, Wang KK, et al. Photodynamic therapy with porfimer sodium for ablation of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus: international, partially blinded, randomized phase III trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overholt BF, Wang KK, Burdick JS, et al. Five-year efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy with Photofrin in Barrett's high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimura S, Ito Y, Nagayo T, et al. Cooperative clinical trial of photodynamic therapy with photofrin II and excimer dye laser for early gastric cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;19:168–172. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)19:2<168::AID-LSM7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, Prasad G, Buttar N, et al. Findings at Esophagectomy After Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR) of Neoplastic Lesions in Barrett's Esophagus. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;61:AB94. [Google Scholar]