Abstract

This paper provides new insights of how general anaesthetic research should be carried out in the future by an analysis of what we know, what we do not know and what we would like to know. I describe previous hypotheses on the mechanism of action of general anaesthetics (GAs) involving membranes and protein receptors. I provide the reasons why the GABA type A receptor, the NMDA receptor and the glycine receptor are strong candidates for the sites of action of GAs. I follow with a review on attempts to provide a mechanism of action, and how future research should be conducted with the help of physical and chemical methods.

Keywords: general anaesthetics, pressure reversal, GABA receptor, glycine receptor, NMDA receptor, membrane

Introduction

General anaesthetics (GAs) have been in use since the mid-19th century. The first such drugs were chloroform and ether. Over time, more chemicals were found to have general anaesthetic action. Towards the middle of the 20th century, the haloalkane gaseous GAs were synthesized, and they have remained the family of GA drugs most widely used. GAs comprise one of the most important drug groups in clinical use. Without them, modern medicine, especially surgery, would not have been possible.

Although the primary event of GAs is loss of consciousness, they have additional actions which include analgesia, amnesia and muscle relaxation. In this review, I focus mainly on their action as agents to cause loss of consciousness. I shall first provide a brief review of previous results, concentrating on those which have an impact on future directions. A recent review has discussed the nervous system pathways involved in greater detail (Franks, 2008), so the main emphasis here is on recent progress towards elucidating the molecular mechanisms of general anaesthesia. I shall also delineate our ignorance to show how far we are from a proper understanding of these mechanisms. Lastly, I provide a ‘road map’ of GA research, to define what is needed to complete our understanding of these drugs, and suggest physical and chemical methods that could potentially revolutionize GA research at the molecular level.

Background

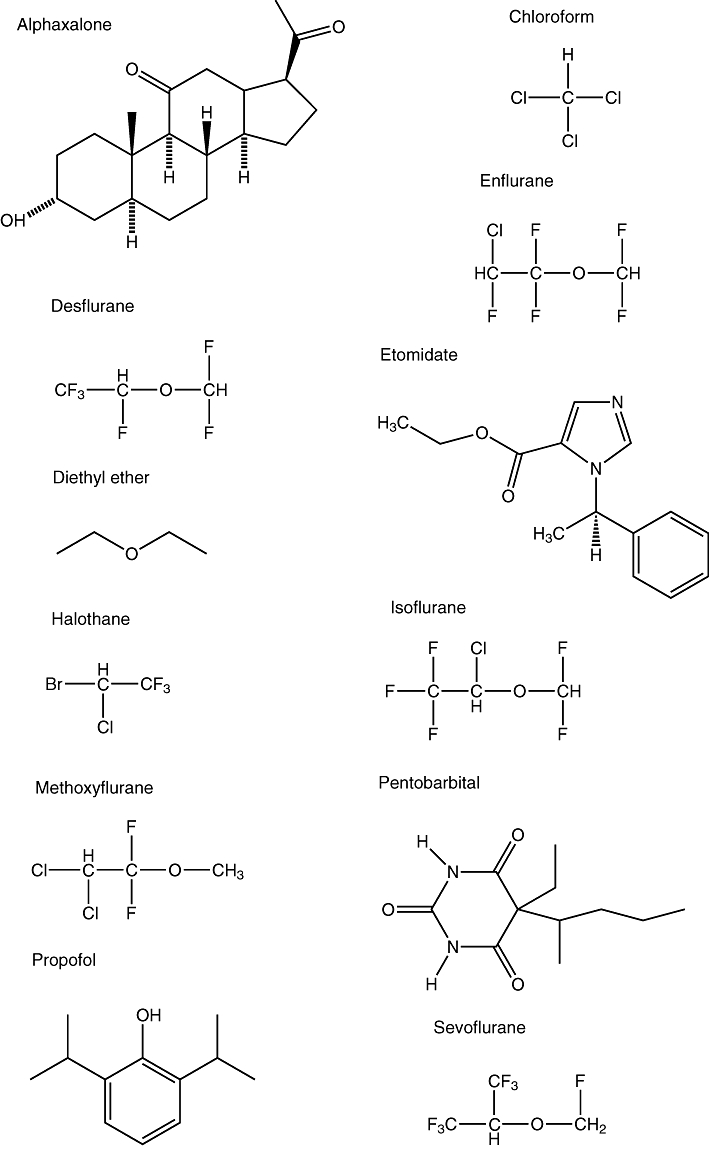

GAs include a large number of drugs. Nitrous oxide (N2O) was discovered to have euphorigenic properties by Humphry Davy as early as 1799, but its GA properties were only discovered in 1844 by Horace Wells. Ether and chloroform were introduced at about the same time. Barbiturates were first synthesized in 1864, but their value as GAs was not recognized until 1903. Etomidate, a non-gaseous GA, was introduced in the 1950s. Halothane was first used in the 1960s; despite the risk of its causing liver damage in a small number of patients, it is still on the WHO Essential Drugs List. In the 1970s, the use of enflurane and isoflurane became more widespread, propofol came onto the market in the mid-1980s, and the 1990s saw the rise of sevoflurane and desflurane. Figure 1 shows the chemical structures of some common GAs.

Figure 1.

Diagrams showing the chemical structures of some common GAs.

Lack of specific binding

In pharmacology, specific binding is very often used to locate the site of action of a drug. This method, however, yielded few useful results for gaseous GAs, because they associate with many proteins non-specifically (they bind to more than one sites). Their EC50 values are mostly of the order of 1 mM, and experiments have shown that they bind to proteins as diverse as myoglobin (Schoenborn et al., 1965), adenylate kinase (Sachsenheimer et al., 1977), cholesterol oxidase (Bertaccini et al., 1998) or even albumin (Bhattacharya et al., 2000). The EC50 values for propofol and etomidate are in the µM ranges, but propofol binds to protein kinase C (Hemmings and Adamo, 1994), the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) (Dilger et al., 1994), the L-type calcium channel (Zhou et al., 1997) and the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (Hales and Lambert, 1991), whereas etomidate binds to the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor (Appadu and Lambert, 1996), the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (Moody et al., 1997) and the α2B-adrenoceptors (Paris et al., 2003).

For this reason, experiments showing parallelism of binding and anaesthetic effects are often used. Indeed, there have been very few studies directly linking binding to anaesthetic effects. A paper by Hemmings et al. (2005) listed four criteria for identifying GA targets: (i) the GA reversibly alters target function at clinically relevant concentrations. In experiments not involving whole animals, this point is of particular importance because a number of GAs only potentiate the effects of a natural neurotransmitter at clinical doses, but at higher doses they directly activate the receptor(s); (ii) the target is expressed in appropriate anatomical locations to mediate the specific behavioural effects of the GA; (iii) the stereo-selective effects of the GA in vivo parallel actions on the target in vitro; (iv) the target exhibits appropriate sensitivity (or insensitivity) to the GAs (or non-GAs). To this, one could add (v) any drug disrupting the functioning of the target also abolishes the effect of GAs.

Lipid solubility and pressure reversal

The first attempt to explain the effect of GAs came in about 1900, when Meyer (1899) and Overton (1901) formulated what became known as the Meyer–Overton rule which related the hydrophobicity of an anaesthetic molecule to its efficacy. Briefly, their observation suggested that the logarithm of the efficacy of an anaesthetic was related to the logarithm of its hydrophobicity. Because the structure of these anaesthetic molecules differed greatly, a working hypothesis was formulated, namely there was a unified mechanism of action for anaesthetics. In the subsequent 50 years or so, experimental data on the efficacy of various chemicals, especially homologous organic series, as GAs, accumulated. The Meyer–Overton rule was found to be only approximate, and a number of compounds do not fit the rule e.g. the homologous series of 1-alkanols have greater efficacy than the rule would predict (Mullins, 1954; Cantor, 2001).

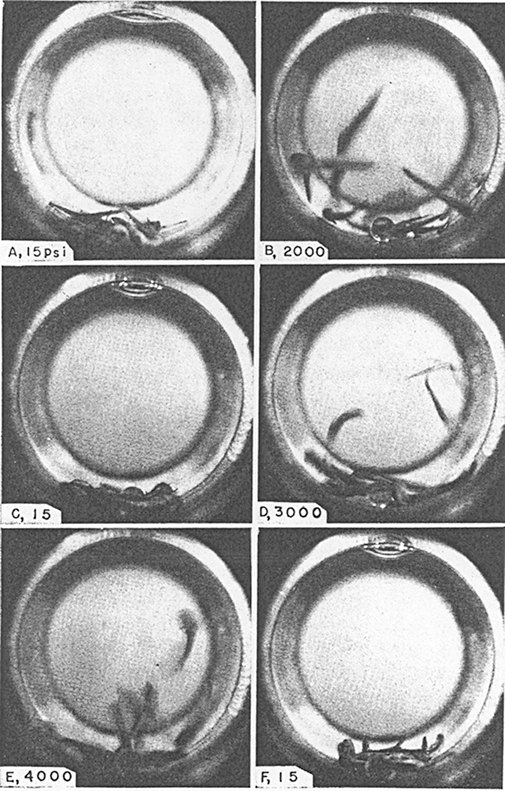

A hint to the mechanism of action of these agents came with the work of Johnson and Flagler (1950), who discovered that, by increasing ambient pressure to 130 atm, anaesthesia by ethanol can be reversed. Figure 2, from the paper of Johnson and Flagler (1951), vividly shows this effect. This work was subsequently extended to Triturus cristatus carnifex (the Italian crested newt) and the mouse by Paton and his co-workers, using different GAs (Lever et al., 1971; Miller et al., 1973), at a pressure of 200 atm. Their results were confirmed by other researchers at similar pressures (Halsey and Wardley-Smith, 1975; Youngson and MacDonald, 1975; Simon et al., 1983; Tonner et al., 1992).

Figure 2.

Diagrams showing the reaction of Amblyostoma larvae to pressure, in the presence of 2.5% ethanol. The pressure inside the vessel is shown in the lower left-hand corner of each panel, 1 psi = 6895 Pa. The six photographs took place over 4 min. Taken from figure 2 of Johnson and Flagler (1951).

Attempts were made to locate the site of pressure reversal. Trudell et al. (1973a) performed electron spin resonance experiments to show that anisotropic motion of phosphatidylcholine within the phospholipid bilayer was increased in the presence of methoxyflurane or halothane (anisotropy means the motion is not the same in all directions). There was a concomitant decrease of the order parameter S′n of the phospholipid as the concentration of anaesthetic increased (Trudell et al., 1973a); the order parameter can be seen as a measure of the conformation of the phospholipid non-polar tails. On application of pressures up to 274 atm by increasing the amount of helium (a non-anaesthetic gas at these pressures) in the container, these changes were reversed: S′n increased and the spectra shifted back (Trudell et al., 1973b). In subsequent work, Trudell et al. (1975) studied the effect of methoxyflurane on the mixed dipalmitoyl–dimyristoylphosphatidyl choline bilayers, and discovered that, at atmospheric pressure, the transition temperature from the gel phase to the lamellar smectic liquid crystalline phase was 22.5 ± 0.5°C for dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC), and 40.9 ± 0.5°C for dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. Pressure drives this phase transition to a higher temperature, but methoxyflurane shifts this phase transition to a lower temperature.

Although the site of pressure reversal appeared to be the membrane, it was not clear where in the body this occurred. Pressure reversal was observed in the action potential in peripheral nerves: high-pressure helium, itself shown not to affect nerve conduction, reversed the reduced action potential height caused by anaesthetics (Roth et al., 1976). The site of action was not the sympathetic nerves in the superior cervical ganglion (Kendig et al., 1975); nor the neuromuscular junction (Kendig and Cohen, 1976); nor the effect caused by a combination of pentobarbitone, N2O or high-pressure N2 gas and GABA on its receptors (Little and Thomas, 1986).

Pressure reversal, although useful as an indicator of GA action, could never be used as a reliable criterion of GA effect. It was not limited to GAs (Halsey and Wardley-Smith, 1975); some other compounds exhibited this effect, and some GAs did not exhibit pressure reversal (Smith et al., 1984). Lastly, Little and Thomas (1986) noted that helium gas alone causes hyperexcitability in the absence of anaesthetics (Halsey, 1982). This gas was sometimes used to increase the pressure in pressure reversal experiments. Pressure reversal may therefore be a whole-animal antagonism involving actions at separate sites, rather than a pharmacological antagonism at the GA site of action (Little and Thomas, 1986). Nevertheless, this is a consistently observed property of most GAs, so any hypothesis attempting to explain GA action must also provide a plausible explanation for these observations.

Stereospecificity and protein receptor hypothesis

Further research showed that the effect of GAs was stereospecific. Harris et al. (1992) studied the sleep time induced by S(+)-isoflurane and R(−)-isoflurane in mice, and found the (+)-enantiomer induced a significantly longer sleep time in the animals. Lysko et al. (1994) studied the effect of the same drug on rats, and found that S(+)-isoflurane was 53% more potent than R(−)-isoflurane.

The stereospecific effects of isoflurane could be consequences of chiral effects of the phospholipid bilayer. Dickinson et al. (1994) examined the partition of isoflurane enantiomers between a cholesterol-containing phospholipid bilayer and water using gas chromatography. They found that lipid solubilities of the isoflurane enantiomers were essentially identical.

A more functional approach was taken by Tomlin et al. (1998) who investigated the effect of etomidate on the righting reflex in Rana temporaria tadpoles. They found that the loss of righting reflex EC50 for R(+)-etomidate was 3.4 ± 0.1 µM, but that for S(−)-etomidate was 57 ± 1 µM, but the effect of these enantiomers on the lipid bilayers was identical.

That the stereospecificity of GAs could not be accounted for by the membrane made scientists search for alternatives, and a large number of proteins were suggested as possible targets. Ultimately, further research has reduced the possibilities down to a few proteins, which will be discussed in the following section.

Recent research

One can divide current GA research into different hierarchical levels. There is work at the molecular level to delineate the site and mechanism of action, work at the pathway level to define the neural mechanism and work at the whole-animal level to determine behavioural effects. Here, we are mainly concerned with molecular-level effects, but I shall briefly describe results from neural pathway research which have impact on research at the molecular level. One can divide recent molecular research into two broad categories: that which involve the membrane and that which involves a receptor.

Competing hypotheses

The fact that GAs were shown to have non-lipid-related stereospecific action gave rise to the idea that these molecules bind to specific non-lipid receptors in the cell (Franks and Lieb, 1984). Four large classes of protein molecules have been postulated to be the main site of action: ligand-gated ion channels, voltage-gated ion channels, enzymes and carrier proteins. Researchers have tried to link GA effect with these proteins. So far, persuasive evidence is available only for two ligand-gated ion channels, the GABA type A receptor (GABAA receptor, see subsection GABAA receptors) and the N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDA-receptor, see subsection NMDA receptor), as the most probable sites of action.

The membrane hypothesis has not been completely abandoned. Some researchers postulate that GAs act on the membrane molecules in the vicinity of membrane protein molecules; this indirect action of GAs changes the functions and properties of these membrane proteins, and causes anaesthesia (Cantor, 1997).

Drug classification

Although the Meyer–Overton rule hinted at the possibility of a unitary mechanism of action of GAs, research evidence is emerging that GAs are probably not a single group of drugs all acting via the same mechanism. A number of separate functional classes of GAs are beginning to emerge.

Based on the putative site and mechanism of action, GAs can be grouped into different classes. Subsections GABAA receptors and NMDA receptor will briefly review the evidence for grouping GAs into the following classes: (i) haloalkanes; (ii) propofol; (iii) etomidate; (iv) barbiturates; (v) neurosteroids; (vi) xenon and N2O (vii) alkanols. The classification of GAs is necessarily very fluid, because our knowledge of these drugs is limited. As new results emerge, this classification will change.

Neuronal pathways

Evidence is emerging that there are similarities but also differences between sleep and anaesthesia (Tung and Mendelson, 2003; Lydic and Baghdoyan, 2005), so understanding these pathways will help us to locate the site of action of GAs.

Our knowledge of sleep–wakefulness pathways began with the work of von Economo, who observed the sleep–wakefulness states of brain-damaged patients of encephalitis lethargica during World War I (von Economo, 1917). He noted that lesions of the posterior hypothalamus and rostral midbrain led to a state of prolonged sleepiness, while lesions of the pre-optic area and basal forebrain led to prolonged insomnia. He therefore suggested that the region of the hypothalamus near the optic chiasma contained sleep-promoting neurons, but posterior hypothalamus contained neurons which promoted the wakeful state (von Economo, 1929).

Over the years, his theory has been shown to stand up reasonably well to scrutiny. The last few decades have seen the discovery of the neuronal circuitry which is responsible for sleep–wakefulness. It is beyond the scope of this work to give a detailed account of these pathways, so I shall concentrate on how knowledge of them has made an impact on GA research.

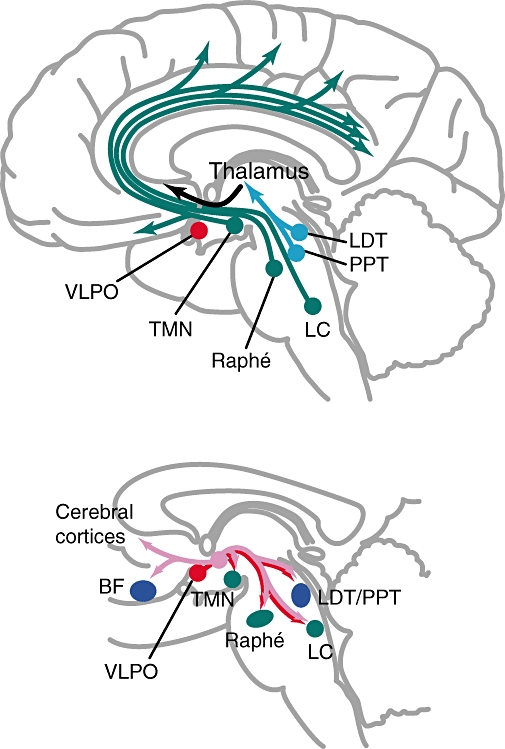

Put simply, there are two main pathways in determining the sleep–wakefulness state (Saper et al., 2001; Jones, 2005). The ascending arousal pathway includes the pedunculo-pontine and latero-dorsal tegmental nuclei which send projections to the thalamus, which are relayed and sent to the cerebral cortices; this pathway also includes ascending projections from the locus coeruleus, raphé and tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN). The descending sleep pathway includes projections from the ventro-lateral pre-optic nucleus and the lateral hypothalamic orexinogenic neurons to the TMN, raphé, locus coeruleus and pedunculo-pontine and latero-dorsal tegmental nuclei; in addition, lateral hypothalamic neurons which release orexin also innervate the cerebral cortices and the basal forebrain. Figure 3 shows the two pathways.

Figure 3.

Diagrams showing the two major pathways determining the sleep–wakefulness cycle. The upper panel shows the ascending arousal pathway. The lower panel shows the descending sleep pathway, where the orexinergic projections are shown in pink, and the other projections in red. BF, basal forebrain; LC, locus coeruleus; LDT, laterodorsal tegmental nuclei; PPT, pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei; VLPO, ventrolateral pre-optic nucleus. Adapted from Hemmings et al. (2005).

The possible sites of action of GAs can be found along the ascending arousal pathway and the descending sleep pathway. Three studies aimed to define the effects of GAs on specific locations of the pathways, and thus used a more direct approach. Nelson et al. (2002) observed that the loss of righting reflex caused by muscimol (a GABAA agonist without GA activity), propofol and pentobarbital was prevented by prior administration of subcutaneous administration of gabazine, a GABAA antagonist. To localize the site of action of the anaesthetics, they used c-fos expression as an index of neuronal activity, and found that muscimol, propofol or pentobarbital increased c-fos expression in the ventro-lateral pre-optic nucleus, but decreased c-fos expression in the hypothalamic TMN. Lastly, the authors micro-injected muscimol directly into the TMN, and caused a loss of righting reflex. Micro-injections of gabazine into the TMN could prevent the hypnotic effect of propofol, and reduce the pentobarbital effect. Sukhotinsky et al. (2007b) micro-injected pentobarbital into the mesopontine tegmental anaesthesia area of conscious rats and showed that this drug reversibly induced an anaesthesia-like state, with loss of consciousness. This effect was attenuated by local pretreatment with bicuculline (a GABAA antagonist). Because pathways mediating immobility (Sukhotinsky et al., 2005) and analgesia (Sukhotinsky et al., 2007a) also project from the mesopontine tegmental anaesthesia area, they suggested that the mesopontine tegmental anaesthesia area could be important in the effect of GAs. Hentschke et al. (2005) compared the effects of halothane, isoflurane and enflurane on the activity of rat neocortical neurons in the whole animal and also of brain slices of the rat neocortex. They observed that the GAs decreased spontaneous firing of neurons to the same extent in both types of experiments, for isoflurane and enflurane, and for halothane at sub-clinical concentrations. For halothane at clinical concentrations, the depression of neocortical activity was different under the two conditions. In all cases, this decrease in neocortical activity was parallelled by enhancement of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition. The authors thus concluded that the neocortical GABAA receptor could be the site of GA action at least at lower concentrations of the drugs.

There were other studies which administered non-GA drugs and thus employed a more indirect approach. For example, Ma et al. (2002) micro-injected muscimol into the hippocampus of rats, and showed that this decreased the dose of halothane, isoflurane or propofol required to induce a loss of righting reflex or a loss of tail-pinch response, thus showing this part of the brain to be important in mediating the loss-of-consciousness and analgesic effect of GAs. In a subsequent paper (Ma and Leung, 2006), the authors further identified parts of the limbic system to be involved in the action of GAs. Alkire et al. (2007) micro-injected nicotine into the central medial thalamus and found that the loss of righting induced by sevoflurane was abolished.

These papers give us some glimpses of which parts of the CNS could be involved in general anaesthesia, but none of them provides us with a conclusive picture of the pathways involved. Logically, the GAs could be acting elsewhere, and that the pathway studied was only a parallel pathway which could override the pathway used by the GA. Care should also be taken in the interpretation of micro-injection experiments; Pilowsky (2004) has discussed the best practice expected of such work, including the publication of experimental details, but not all papers follow these guidelines rigorously. However, these studies have demonstrated the importance of the GABAA receptor, and it is to this protein that we shall turn.

Protein receptor hypothesis: neurophysiology

The protein receptor hypothesis suggests that the target of GAs is a protein. There are four main candidates.

GABAA receptors

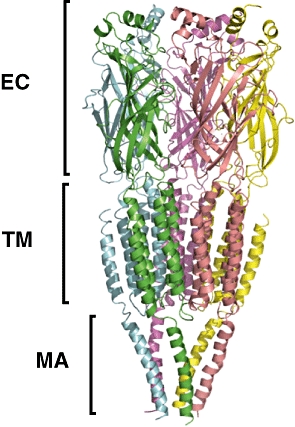

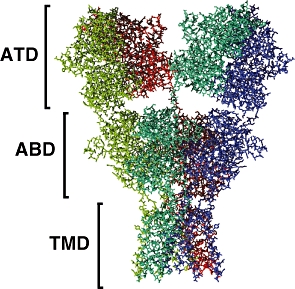

The family of GABAA receptors is responsible for the majority of fast neuronal inhibition in the mammalian CNS, and is thought to be a target of GAs. These oligomeric proteins belong to the cys-loop family of ligand-gated ion channels that includes the nicotinic acetylcholine, glycine and 5HT3 receptors. The GABAA receptors are composed of five subunits arranged pseudosymmetrically around the integral anion channel (Nayeem et al., 1994). The subunits, of which 19 have thus far been identified, are separated into classes based on their sequence similarity: there are six α-subunits; three β; three γ; three ρ; and single representatives of δ, ε, θ and π. The precise subunit isoform composition of the oligomer defines the recognition and biophysical characteristics of the particular receptor subtype. The most ubiquitous subtype, which accounts for approximately 30% of GABAA receptors in the mammalian brain (Whiting, 2003), contains two α1-, two β2- and a single γ2-subunit (Farrar et al., 1999). The GABAA receptors can be divided into three structural domains: extracellular (EC) domain, transmembrane (TM) domain and intracellular (IC) domain. Figures 4 and 5 show a modelled structure of the GABAA receptor, subtype (α1)2(β2)2γ2, taken from the work of Mokrab et al. (2007).

Figure 4.

Side view of a similarity model of the GABAA receptor, subtype (α1)2(β2)2γ2. The five subunits are shown in different colours. The extent of the extracelular domains are labelled EC, that of the TMDs TM and that of the helices of the intracellular domain are labelled MA. Note that the intracellular domain consists of more than five helices, but only these structures could be modelled. Taken from figure 4 of Mokrab et al. (2007).

Figure 5.

View of the same similarity model from the extracellular space towards the intracellular space (the ‘top’ view). The five different subunits are labelled. Taken from figure 5 of Mokrab et al. (2007).

The first indication that GABA might be implicated in the general anaesthetic response came from Hales and Lambert (1991) who noted that propofol potentiated the effect of GABA on its type A receptor at concentrations similar to clinical ones, although in the absence of GABA this drug was without effect. Orser and her co-workers studied the effect of this drug on GABAA receptors on mouse hippocampal neurons, and found that propofol increased the Cl- conductance of the receptors in a dose-dependent manner (Orser et al., 1994). Jones and Harrison (1993), Moody et al. (1993) and Hall et al. (1994) were the first to note that the stereospecific action of isoflurane in vivo was very similar to its action on the GABAA receptor complex. Tomlin et al. (1998) discovered that the stereoselective effects of etomidate were similar to its action on this receptor.

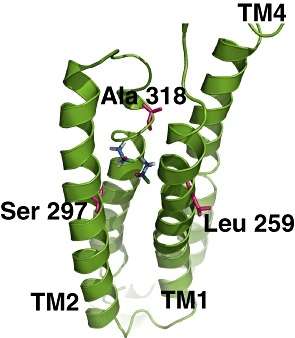

Since then, there have been a large number of studies linking the effect of GAs to altered function of the GABAA receptors. All of them agree on one point: GAs at clinical concentrations are without effect unless GABA is also present (at higher concentrations, many drugs exert a direct effect on the GABAA receptor, but this effect is unrelated to the clinical use of GAs). Most of them also noted that particular amino acid mutations caused changes in GA effects. These results are summarized in Table 1, and they show that the GAs acting on the GABAA receptor could be divided into several groups, depending on their binding site. The first group, the haloalkane GAs, all sharing overlapping sites near all four transmembrane domains (TMDs) of the α-subunits (Mihic et al., 1997; Jenkins et al., 2001; 2002), near Ser 297 and Ala 318 (Mokrab et al., 2007). Propofol and etomidate, respectively, form two separate groups, because they have different binding patterns from the haloalkanes (Krasowski et al., 1998), near the M2 and M3 domains of the β-subunit. Propofol also affects the M4 domain of the β-subunit (Richardson et al., 2007), but does not appear to bind to the α-subunit (Bali and Akabas, 2004), while etomidate probably binds near the M1 domain of the α-subunit (Li et al., 2006). The barbiturates are in a class of its own; they require amino acids in the M1 and M2 domains of the β-subunit (Dalziel et al., 1999; Pistis et al., 1999), and loop D of the extracellular domain of the α-subunit (Drafts and Fisher, 2006) to exert their action. Neurosteroids should also be mentioned, although their use is confined to veterinary medicine; the drug probably binds between the M1 and M4 domains of the α-subunits (Hosie et al., 2006). Lastly, the alkanols should be in a separate group because although it acts on the GABAA receptor, it has wide-ranging effects on other receptors (Pohorecky and Brick, 1988).

Table 1.

Point mutations on the GABAA receptor affecting the effect of GAs

Abbreviations used for the drugs: chl, chloroform; des, desflurane; enfl, enflurane; ether, diethyl ether; eth, ethanol; etom, etomidate; isofl, isoflurane; mexyfl, methoxyflurane; ppb, pentobarbital; pro, propofol; sevo, sevoflurane.

There are two methods to localize the binding site of GAs more directly. One is by mutating an amino acid at the putative binding site to Cys, and then measuring the reactivity of sulphydryl reagents in the presence and absence of GAs. This approach has identified α2-S270 of the TM2 domain of the GABAA receptor to be near the binding site of enflurane and isoflurane (Mascia et al., 2000), and β2-M286 of the TM3 domain to be near the binding site of propofol (Bali and Akabas, 2004). The other method is to use a photo-affinity analogue of the GA and observe its binding; such analogues of haloalkanes (Eckenhoff et al., 2002) and etomidate (Husain et al., 2003) have been synthesized. Li et al. (2006) used 3H-azi-etomidate photo-affinity labelling to identify α1-M236 and β3-M286 of the GABAA receptor to be near the etomidate binding site.

Volume estimates were made on the putative GA binding site. Jenkins et al. (2001) noted that different haloalkane GAs were of different sizes, and that mutations of the α-subunit Ser 270 could abolish GABAA receptor modulation by these drugs. They produced a series of mutants of this Ser 270 of different sizes, and were able to estimate the volume of a proposed haloalkane binding site to be 250–370 Å3. Their results thus suggest a common site of action for isoflurane, halothane and chloroform, which is only large enough to accommodate one GA molecule. Krasowski et al. (2001) used a similar approach on the β2-M286, and estimated the propofol binding site to have a volume of about 200 Å3.

These studies suffer from the fact that only receptor responses were examined, but general anaesthesia is a whole-animal effect, and an altered receptor response cannot be used to demonstrate definitively the effect of GAs. A transgenic animal approach therefore was adopted by other researchers. Homanics et al. (1997) engineered a mouse strain without the α6 subunit, and found that the mutant animal did not exhibit any altered response to GAs. Ugarte et al. (2000) engineered a strain of knockout mice lacking the β3 subunit of the GABAA receptor, and found that they have lower pain thresholds; the analgesic part of general anaesthesia could thus be mediated by GABAA receptors. Cheng et al. (2006) produced mutant mice lacking the α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor, and found that etomidate retained its amnestic effect but not the hypnotic effects. Borghese et al. (2006) engineered mutant mice with both S270H and L277A mutations in their GABAA receptor α1-subunit, and showed that the response of these mice to GABA was almost normal. Nevertheless, they exhibited reduced sensitivity to isoflurane but not to halothane. In a subsequent paper, Sonner et al. (2007) showed that these mice possessed altered loss of righting reflexes to gaseous GAs; the drugs had no effects on the amnestic nor the immobilizing effects on the mice. These results are highly suggestive, but one must bear in mind that functional compensation can occur in transgenic animals. Lastly, whole-animal electrophysiological study described earlier (Nelson et al., 2002) has linked molecular effects to whole-animal effects.

The evidence for the involvement of the GABAA receptor in GA effects, although circumstantial, is thus quite strong, with a high probability that the gaseous haloalkanes, etomidate and the barbiturates interact with different regions of the α- and β-subunits, while propofol binds to the β-subunit. Propofol does not appear to bind to the the α-subunit.

NMDA receptor

Glutamate is a neurotransmitter in the CNS and acts on three classes of receptors named after their selective agonists: NMDA, AMPA and kainate. The NMDA receptor is a tetrameric receptor (Behe et al., 1995; Premkumar and Auerbach, 1997; Laube et al., 1998). There are two known classes of subunits, named NR1 and NR2, the latter with four subtypes called NR2A to NR2D. Each subunit consists of an extracellular amino-terminal domain (ATD), an extracellular agonist-binding domain (ABD), a TMD and a C-terminal intracellular domain (Wood et al., 1995; Paoletti and Neyton, 2007). NMDA receptors are slow-acting excitatory receptors, with the activation process occuring on a scale of tens to hundreds of milliseconds.

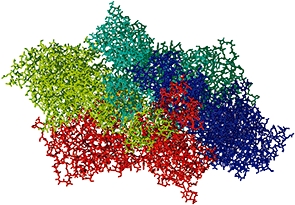

The structure of the NMDA receptor has not been determined experimentally, but that of the AMPA receptor is available (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). This receptor consists of a large extracellular part which comprises the ATD and ABD, and which displays a twofold axis of symmetry. The TMD, on the other hand, has a fourfold axis of symmetry centred around the ion channel. Figures 6 and 7 show the structure of this AMPA receptor. The NMDA receptor is believed to possess a similar structure.

Figure 6.

Side view of the AMPA receptor, showing the ATD, ABD and TMD. The four subunits are shown in different colours. Atomic coordinates of the intracellular domain are not available. Drawn from the PDB data set 3KG2 (Sobolevsky et al., 2009).

Figure 7.

View of the AMPA receptor from the extracellular space towards the intracellular space (the ‘top’ view).

The NMDA receptor probably mediates the effect of xenon (de Sousa et al., 2000) and N2O (Jevtović-Todorovićet al., 1995). Franks et al. (1998) showed that xenon reduces the NMDA-activated currents in hippocampal neurons, and Dickinson et al. (2007) identified a putative binding site using single-cell experiments and modelling. Using a transgenic approach, Sato et al. (2005) showed that the sensitivity to N2O was significantly reduced in knockout mice lacking the NR2A subunit (coded for by the ε1-subunit gene) of the NMDA receptor, but the effects of sevoflurane were unaffected. This remains the most convincing result to date which implicates the NMDA receptor in the action of nitrous oxide, but one must remain alert to the possibility of functional compensation in transgenic animals. Haloalkanes also reduce the NMDA-activated currents in this receptor, but their effects are less prominent than those on the GABAA receptor (Martin et al., 1995; Hollmann et al., 2001; Solt et al., 2006), so the role of haloalkanes on this receptor in anaesthesia is unclear.

Glycine receptor

Glycine, like GABA, is an inhibitory neurotransmtter. The glycine receptor is also a cys-loop receptor, so its structural motifs are similar to those of the GABAA receptor. There are two classes of subunits for this receptor, α and β. The α-subunits consist of four subtypes, α1 to α4 (Matzenbach et al., 1994), while only one subtype exists for the β-subunit (Handford et al., 1996). On agonist binding, the glycine receptor opens the central ion channel to allow chloride ions through; it is usually part of an inhibitory synapse (Curtis et al., 1967; 1968). Extensive work has been published on the glycine receptor which showed the modulatory effect of GAs on this receptor (Mihic et al., 1997; Ye et al., 1998; Yamakura et al., 1999; Krasowski and Harrison, 2000; Beckstead et al., 2001; 2002; Ahrens et al., 2008).

Ye et al. (2009) experimented on rats and showed that strychnine abolished the loss of righting reflex induced by ethanol, but not that induced by ketamine, and concluded that the glycine receptor was implicated in ethanol effects. Nguyen et al. (2009) performed experiments on whole rats and rat brain slices to show that propofol potentiated the effect of glycine on its receptor, and that this effect was blocked by strychnine. However, they used a high concentration of propofol capable of direct activation of the glycine receptor. Further studies are needed to establish the exact role of this receptor in GA effects, and also to identify the location of these receptors on the sleep–wakefulness pathway.

Potassium channels

It has been known for a long time that GAs hyperpolarize neurons by acting on the potassium currents (Nicoll and Madison, 1982; Berg-Johnsen and Langmoen, 1986; 1987; Franks and Lieb, 1988; Sugiyama et al., 1992). One of the putative targets of GAs was identified as the two-pore-domain K+ channel. These K+ channels contain four TMDs and two ion channels in tandem (Fink et al., 1996; Lesage et al., 1996; Duprat et al., 1997; Fink et al., 1998).

Tissue studies have been performed on these K+ channels. Patel et al. (1999) examined TASK and TREK-1, and found that TREK-1 was activated by chloroform, diethyl ether, halothane and isoflurane, while TASK was activated by halothane and isoflurane. Liu et al. (2004) engineered human TRESK channels into the Xenopus oocyte, and noted that their outward currents were potentiated 1.5- to 3-fold by different haloalkane GAs. Gruss et al. (2004) expressed TREK-1 channels on HEK-293 cells and showed that TREK-1 currents were enhanced by nitrous oxide, xenon, cyclopropane and halothane. Andres-Enguix et al. (2009) cloned a TASK channel from the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis and discovered that it was preferentially activated by (+)-isoflurane; this was also observed in mice (Harris et al., 1992) and rats (Lysko et al., 1994).

Heurteaux et al. (2004) engineered a transgenic Trek −/− mouse and found that the loss of righting reflex was observed in lower concentrations of chloroform, halothane, sevoflurane and desflurane in the mutant mouse than in the wild type. This result is highly suggestive, but one must bear in mind that functional compensation can occur in transgenic animals. Further studies are required to establish the exact role of these K+ channels in GA action.

Other possible candidates

The nAChR has been shown to bind GAs (Forman et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1997; Pratt et al., 2000; Yamashita et al., 2005), but all these studies only show parallelism of drug association with GA effect in cells or tissues, and none of them could directly link binding to whole-animal GA effects; general anaesthesia, by definition, can only be observed in a whole animal, not in brain slices or cell cultures.

Protein receptor hypothesis: molecular mechanisms

Surprisingly, little has been written on actual molecular mechanisms involved in general anaesthesia. The lack of a structure of any of the putative receptors at atomic resolution is the main stumbling block to further progress. One way forward is to model the structure of these proteins using similarity modelling methods. Since the publication of the 4 Å structure of the nAChR (Unwin, 2005), PDB code 2BG9, its coordinates have been used for a number of GABAA receptor models (Ernst et al., 2005; Mokrab et al., 2007) where GAs were docked to the modelled structure (Figure 8). The problem with these results is that they have yet to await experimental confirmation. None of these studies have attempted to propose a molecular mechanism of action.

Figure 8.

View of two possible binding positions of halothane to the α1-subunit of a model of the GABAA receptor. The transmembrane helices, labelled TM1 to TM4, are shown in green. The carbon atoms of halothane are shown in blue. Amino acids shown to be involved in binding are shown in magenta and labelled. Taken from figure 13 of Mokrab et al. (2007).

Horenstein et al. (2001) produced Cys mutants of amino acids of the M2 helix of an α3β2 subtype of the GABAA receptor, and examined the possibility of forming disulphide bridges in the presence or absence of GABA, under reducing or oxidizing conditions. They found that 6′ disulphide bridges formed between adjacent subunits in the open, but not the closed state. They reasoned that this implies the M2 helices rotate on activation by the agonist. They engineered five different mutants of the (α1)2(β2)2γ subtype of the GABAA receptor, and attached fluorophores to the mutated Cys. They discovered that there was a closure of the GABA-binding cavity at the subunit interface (Muroi et al., 2006). Using the same technique, they identified residues in the α1 and β2 pre-M1 region important in gating (Mercado and Czajkowski, 2006). They also investigated the effect of pentobarbital on some of these mutants (Muroi et al., 2009), and noted that at concentrations which produced clinical anaesthesia, pentobarbital changed the fluorescence of the probe attached to the β2-K274C mutant Cys when no γ2 subunits were present in the receptor. GABA, on the other hand, elicited a fluorescence change of the opposite sign. Thus, it appears the channel-opening mechanisms used by GABA and by pentobarbital are different. One should note that all these studies attached mutant Cys to large fluorescent groups, so the mutation and steric effects should be borne in mind when interpreting the results.

A completely different direction was taken by Roth et al. (2008), who suggested that the gating of ion channels was caused by the formation and disapperance of bubbles. They also suggested that xenon caused anaesthesia by inserting into the ion channel, and thus increasing the probability of bubble formation, and that high pressure reverses the effect of xenon. Using simple models, they produced results which showed the feasibility of this hypothesis. Unfortunately, they still viewed the Meyer–Overton rule as a useful guide to the unitary mechanism of GA action, while we know that many drugs violate the Meyer–Overton rule and the unitary mechanism is probably no longer tenable (Mullins, 1954; Cantor, 2001). This hypothesis is unable to account for the stereospecificity of GAs. It would seem that it might be unable to account for the effect of GAs of larger sizes, such as diethyl ether, isoflurane or enflurane.

Thus, so far, no concrete molecular mechanism has been proposed for GA action. The main difficulty of proposing a hypothesis for GA action is that we still do not quite know how the putative GA receptors open their ion channels on agonist binding, let alone how this opening can be modulated. Until and unless this is established, it would be impossible to suggest a falsifiable hypothesis of how GAs work.

Membrane hypothesis

It is obvious from previous research that the membrane is involved in GA effects, but it is unclear how. Research on this front can be divided under three headings: where the GAs go inside the membrane, what they do to the membrane and how all this relates to GA effects.

Previous experiments have shown that GAs partition to the area of the membrane near the interfacial and non-polar regions of the membrane (Yokono et al., 1989; Tang et al., 1997; Feller et al., 2002; Carnini et al., 2004). Results from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations were consistent with these results (Tu et al., 1998; Koubi et al., 2002). Simulations basically create an artifical world, and use this artificial world to examine the properties of the system under study. With current supercomputers, it is possible to perform atomistic molecular dynamics simulations of membrane protein complexes consisting of hundreds of thousands of atoms, and for tens of nanoseconds of simulated time. The structural and dynamic properties of the system can be obtained from the trajectory, and free energy changes of different processes evaluated (Chau, 2006).

Cantor (1997; 2001) suggested that the lateral pressure profile in a membrane was not uniform, GAs perturbed this pressure profile and this shifted the equilibrium of the conformation change of proteins; this was the basis of GA effects. Griepernau and Böckmann (2008) performed molecular dynamics simulations of a DMPC bilayer at 1 and 1000 atm pressure, and explored the effect of dissolving four types of 1-alkanols in them. They showed that the local lateral pressure profile changed on addition of 1-alkanols, but this change was not reversed at high pressure. Nevertheless, asuming a bent helix model for the target protein, they found that high pressure would reverse the effect of 1-alkanols on the protein.

Although this hypothesis provides an explanation for the GA molecules which do not obey the Meyer–Overton rule, it has a number of weaknesses. Firstly, the lateral pressure of a membrane is not uniquely defined; it cannot be measured, although some indication of the pressure changes could be obtained from indicator molecules (Templer et al., 1998; Kamo et al., 2006). So almost all the work supporting it come from simulations. Secondly, the lateral pressure effect does not correlate with the GA effect. Simulations showed that the alkanols had little effect on membrane lateral pressure (Terama et al., 2008), but the effect of sterols on membrane lateral pressure was much greater (Ollila et al., 2007). This hypothesis has not explained why most sterols are not anaesthetics, but ethanol is. Thirdly, this work is very context dependent. The work of Griepernau and Böckmann (2008) goes some way towards incorporating pressure reversal with GA effects mediated via lateral pressure profiles, but it also shows that the applicability of this hypothesis depends crucially on the mechanism of action of the target protein. Their work was partly carried out at 1000 atm, which is beyond where pressure reversal takes place, so its relevance is doubtful. Lastly, the hypothesis is extremely sparse on essential details, such as which protein(s) would be the intended target. Without such information, this hypothesis could only be tested for its feasibility, and is not really a falsifiable hypothesis.

Membrane simulations are now developing in three main directions. In one direction is the development of coarse-grain simulations to study the interaction of GAs and membranes (Pickholz et al., 2005). These simulations treat four atoms as one sphere, while in classical molecular dynamics simulations, each atom is treated as one sphere. This allows us to access longer timescales and larger length scales, but care must be taken to treat the solvents correctly (Bock et al., 2007).

In the second direction, peptides or proteins are placed in membranes, and classical molecular dynamics simulations are performed. Tang and Xu (2002) placed gramicidin in a hydrated DMPC bilayer and showed that halothane profoundly changes the dynamics of the protein. Vemparala et al. (2006) placed the transmembrane helices of the nAChR α- and δ-subunits in a hydrated DOPC bilayer, and showed that halothane significantly altered protein dynamics; similar results were obtained on the KirBac1.1 potassium channel (Vemparala et al., 2008). Combined experiment and simulation studies have also been carried out on ‘designer’ proteins (Cui et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Strzalka et al., 2009; Zou et al., 2009). However, these peptides/proteins are not true GA targets, so whether these results are relevant to general anaesthesia is unknown.

The work of Chau et al. (2007; 2009) took a different direction by going back to pressure reversal. Using molecular dynamics simulations, they showed that, at 200 atm, halothane molecules inside a DMPC bilayer tended to aggregate. The formation of these clusters was reversible on taking the pressure back to 1 atm. Drawing on previous work by Jenkins et al. (2001) which showed that the binding site for haloalkane GAs in the GABAA receptor could only accommodate one molecule, they proposed that pressure reversal occurred when halothane aggregated, so fewer monomeric halothane was available to bind to the putative binding site. Thus, their work suggests that although the membrane plays an important role in general anaesthesia, it is a pharmacokinetic effect, not a pharmacodynamic effect. The weakness of this hypothesis is that they used a concentration of halothane three times that of clinical concentration. There is as yet no experimental verification of this effect; only very delicate neutron reflectometry and X-ray scattering experiments would be capable of verifying the aggregation hypothesis. It is also not known if this effect is peculiar to the halothane/DMPC combination or if it is a more general effect.

Future directions

There are a number of obstacles to be obviated before further progress is possible.

The first problem concerns neural pathways. Our understanding of what anaesthesia is in terms of neurology is still incomplete. There have been persuasive studies showing the involvement of different protein receptors on different pathways. However, logically, the GAs could be acting elsewhere, and that the pathway studied was only a parallel pathway which could override the pathway used by the GA. We would need some more definitive demonstration of the pathway and receptors involved in anaesthesia. This is particularly pertinent in terms of the different effects of GAs: loss of consciousness, muscle relaxation, amnesia and analgesia are thought to be modulated by different receptor proteins (Reynolds et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2006; Irifune et al., 2007; Rau et al., 2009). However, different receptor proteins reside on different parts of the CNS, especially in the case of the different GABAA receptor subtypes (Barnard et al., 1998; Pirker et al., 2000). Some are synaptic mediating classical phasic inhibition, while others are extra-synaptic mediating tonic inhibition (Belelli et al., 2009). Preliminary results suggest that different GAs might affect different receptor subtypes (Kitamura et al., 2003; Bieda and MacIver, 2004). How are the different receptor subtypes distributed on different pathways, and how does this distribution, and their diverse functions, relate to the different effects of the GAs? Novel electrophysiological techniques, in vivo genetics and high-resolution brain imaging methods might help us to answer some of these questions.

At the molecular level, one needs to define the structure and mechanism of action of the putative receptors, namely the GABAA receptor, NMDA receptor, glycine receptor and possibly the two-pore potassium channels. The structures of these receptors have not been determined, so our knowledge of their structures is inferred from mutagenesis, photo-affinity labelling experiments and modelling. This is not a desirable state of affairs, as these indirect methods have limited accuracy. There have been suggestions that the development of an X-ray free electron laser could revolutionize the determination of protein structures, by using an intense but ultra-short light pulse to obtain data (Neutze et al., 2004). It would be interesting to see if this exciting new method can be extended for the determination of membrane proteins.

Without more accurate and precise information about their sturctures, it would be extremely difficult to delineate the mechanism of action of these proteins, and how their functioning is altered in the presence of GAs. Most of the studies on ion channel function have only proposed which amino acid is important for the function; they do not propose a precise mechanism of how ligand binding increases the probability of the ion channel opening via the changes of certain dihedral angles, how the ion hydration changes as it traverses the ion channel and how GAs alter the movements brought about by ligand binding. Some scientists have suggested some notions of how GAs would change protein movement, but the suggested mechanism is so vague as to be unfalsifiable. This is where spectroscopy might conceivably be of help.

Spectroscopy is the study of the absorption or emission of electromagnetic radiation by molecules. Spectroscopic experiments provide us with the frequencies of the radiation, and the amount of radiation absorbed or emitted, by the sample. In the case of protein studies, the radiation absorbed by a vibrating C = O bond in the peptide link is in the mid-infrared range (frequency around 5 × 1013 Hz). When the secondary structure of the protein changes, this so-called amide (I) absorption band changes, and the radiation absorbed changes, and from this we can infer the change in protein structure. Thus, infrared spectroscopy is of use in studying protein conformation changes. It has contributed to our understanding of the structural changes of the protein rhodopsin II when it binds the cofactor retinal and transports ions (Jiang et al., 2008), and those of the MelB protein when it binds the ligand melibiose (Lórenz-Fonfría et al., 2009). Coupled with protein structure data, this method can be developed to define protein movement on ligand binding, and how this movement is changed by the presence of GAs. As an aside, one could add that the pre-existent data seem to favour a ‘door wedge’ hypothesis for GA action. At clinical doses, GAs only affect the putative receptor if an agonist is already acting on the receptor; on their own, the drugs do not affect the protein. The GA molecule thus acts like a door wedge. It does not open the door, but keeps the door open for longer. The mechanistic details of this hypothesis remains to be demonstrated, and infrared spectroscopy can be a useful tool. A prediction of this hypothesis is that there are no antagonists of GAs, and to date, none has been discovered.

Lastly, there is always the problem of pressure reversal. Little of the protein receptor work has approached this peculiar property of GAs. Is it an effect at the level of the whole CNS (Halsey, 1982; Little and Thomas, 1986), or is it an effect at the molecular level (Trudell et al., 1973a,b; 1975; Chau et al., 2007; 2009)? Recent research has swung towards a protein receptor for GAs, and the evidence is quite persuasive. However, there is also experimental evidence which suggests the importance of the membrane in GA action, especially in pressure reversal. Work is needed to unravel this part of the GA puzzle.

Conclusions

GAs have been in use for over one and a half centuries, but their mechanism of action still eludes pharmacologists. We now understand a bit more than we did before; the unitary mechanism hypothesis has given way to the multiple-receptor hypothesis. Unfortunately, this makes the whole subject even more complex.

In this paper, I have reviewed the recent advances, described the gaps in our knowledge and suggested what is needed to arrive at a molecular mechanism for GA action. GA research has so far lacked a clear, falsifiable hypothesis. In this work, I have spelt out the ‘door wedge hypothesis’ which we should try to falsify or demonstrate. Historically, most biomedical advances have been contingent upon advances in physics and chemistry, and the application of those techniques in biology and medicine. I have thus briefly reviewed some of the relevant physical and chemical methods, and explored the opportunities these methods can offer for investigating GA effects at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Ian Martin, Susan Dunn, Andrew Hardwick, Anna Armstrong and Maha Shuayb for invaluable comments; Leung Hin-Tak and Tu Kai-min for technical help; and Liang Kuo-Kan for a short-term visiting fellowship in the Academia Sinica, Republic of China, during which time most of this paper was written. Drug and molecular target nomenclature in this paper conforms to the BJP's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2008).

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Supplemental material

Supporting Information: Teaching Materials; Figs 1–8 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Ahrens J, Leuwer M, Stachura S, Krampfl K, Belelli D, Lambert JJ, et al. A transmembrane residue influences the interaction of propofol with the strychnine-sensitive glycine α1- and α1β-receptor. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1875–1883. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181875a31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels, 3rd edition (2008 revision) Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkire MT, McReynolds JR, Hahn EL, Trivedi AN. Thalamic microinjection of nicotine reverses sevoflurane-induced loss of right reflex in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:264–272. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270741.33766.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres-Enguix I, Caley A, Yustos R, Schumacher MA, Spanu PD, Dickinson R, et al. Determinants of the anesthetic sensitivity of two-pore domain acid-sensitive potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;282:20977–20990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appadu BL, Lambert DG. Interaction of IV anaesthetic agents with 5-HT3 receptors. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:271–273. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali M, Akabas MH. Defining the propofol binding site location on the GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:68–76. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olwen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead MJ, Phelan R, Mihic SJ. Antagonism of inhalant and volatile anesthetic enhancement of glycine receptor function. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24959–24964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead MJ, Phelan R, Trudell JR, Bianchini MJ, Mihic SJ. Anesthetic and ethanol effects on spontaneously opening glycine receptor channels. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1343–1351. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behe P, Stern P, Wyllie DJA, Nassar M, Schoepfer R, Colquhoun D. Determination of NMDA NR1 subunit copy number in recombinant NMDA receptors. Proc R Soc. 1995;B110:205–213. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Harrison NL, Maguire J, MacDonald RL, Walker MC, Cope DW. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors: form, pharmacology and function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12757–12763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Johnsen J, Langmoen I. Isoflurance effects in rat hippocampal cortex: a quantitative evaluation of different cellular sites of action. Acta Physiol Scand. 1986;128:613–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1986.tb08019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Johnsen J, Langmoen I. Isoflurance hyperpolarizes neurones in rat and human cerebral cortex. Acta Physiol Scand. 1987;130:679–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1987.tb08192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertaccini E, Trudell J, Brick P, Lieb WR, Franks NP. The interaction of halothane with the binding site of a functional protein, cholesterol oxidase. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:A98. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya AA, Curry S, Franks NP. Binding of the general anesthetics propofol and halothane to human serum albumin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38731–38738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieda MC, MacIver MB. Major role for tonic GABAA conductances in anesthetic suppression of intrinsic neuronal excitability. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1658–1667. doi: 10.1152/jn.00223.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock H, Gubbins KE, Klapp SHL. Coarse graining of nonbonded degrees of freedom. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:267801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.267801. 4 pages. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese CM, Werner DF, Topf N, Baron NV, Henderson LA, Boehm SL, et al. An isoflurane- and alcohol-insensitive mutant GABAA receptor α1 subunit with near-normal apparent affinity for GABA: characterization in heterologous sytems and production of knockin mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:208–218. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor R. The lateral pressure profile in membranes: a physical mechanism of general anesthesia. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2339–2344. doi: 10.1021/bi9627323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor R. Breaking the Meyer–Overton rule: predicted effects of varying stiffness and interfacial activity on the intrinsic potency of anesthetics. Biophys J. 2001;80:2284–2297. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BX, Engblom AC, Kristiansen U, Schuousboe A, Olsen RW. A single glycine residue at the entrance to the first membrane-spanning domain of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor β2 subunit affects allosteric sensitivity to GABA and anesthetics. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:474–484. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnini A, Phillips HA, Shamrakov LG, Cramb DT. Revisiting lipid–general anesthetic interactions (II): halothane location and changes in lipid bilayer microenvironment monitored by fluorescence. Can J Chem. 2004;82:1139–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Chau P-L. Simulations of biomolecule unbinding from proteins using DL_POLY. Mol Simul. 2006;32:953–961. [Google Scholar]

- Chau P-L, Hoang P, Picaud S, Jedlovszky P. A possible mechanism for pressure reversal of general anaesthetics from molecular simulations. Chem Phys Lett. 2007;438:294–297. [Google Scholar]

- Chau P-L, Jedlovszky P, Hoang P, Picaud S. Pressure reversal of general anaesthetics: a possible mechanism from molecular dynamics simulations. J Mol Liq. 2009;147:128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng VY, Martin LJ, Elliott EM, Kim JH, Mount HTJ, Taverna FA, et al. α5 GABAA receptors mediate the amnestic but not sedative–hypnotic effects of the general anesthetics etomidate. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3713–3720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5024-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui T, Bondarenko V, Ma D, Canlas C, Brandon NR, Johansson JS, et al. Four-α-helix bundle with designed anesthetic binding pockets. Part I: halothane effects on structure and dynamics. Biophys J. 2008;94:4464–4472. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DR, Hosli L, Johnston GA. Inhibition of spinal neurons by glycine. Nature. 1967;215:1502–1503. doi: 10.1038/2151502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DR, Hosli L, Johnston GA. A pharmacological study of the depression of spinal neurones by glycine and related amino acids. Exp Brain Res. 1968;5:235–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00235443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel JE, Cox GB, Gage PW, Birnir B. Mutant human α1β1(T262Q) GABAA receptors are directly activated but not modulated by pentobarbital. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;385:283–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00710-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai R, Ruesch D, Forman SA. γ-Amino butyric acid type A receptor mutations at β2 N265 alter etomidate efficacy while preserving basal and agonist-dependent activity. Anesthesiology. 2009;107:264–272. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b55fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson R, Franks NP, Lieb WR. Can the stereoselective effects of the anesthetic isoflurane be accounted for by lipid solubility? Biophys J. 1994;66:2019–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80994-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson R, Petersen BK, Banks P, Simillis C, Martin JCS, Valenzuela CA, et al. Competitve inhibition at the glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor by the anesthetics xenon and isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:756–767. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000287061.77674.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilger JP, Vidal AM, Mody HI, Liu Y. Evidence for direct actions of general anesthetics on an ion-channel protein – a new look at a unified mechanism of action. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:431–442. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drafts BC, Fisher JL. Identification of structures within GABAA receptor α subunits that regulate the agonist action of pentobarbital. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1094–1101. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler B, Jurd R, Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Dual actions of enflurane on postsynaptic currents abolished by the γ-aminobutyric acid type a receptor β3(N265M) point mutation. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:297–304. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprat F, Lesage F, Fink M, Reyes R, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. TASK, a human background K+ channel to sense external pH variations near physiological pH. EMBO J. 1997;16:5464–5471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff RG, Knoll FJ, Greenblatt EP, Dailey WP. Halogenated diazirines as photolabel mimics of the inhaled haloalkane anesthetics. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1879–1886. doi: 10.1021/jm0104926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Economo C. Encephalitis lethargica. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1917;30:581–585. [Google Scholar]

- von Economo C. Schlaftheorie. Ergeb Physiol. 1929;28:312–339. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Bruckner S, Boresch S, Sieghart W. Comparative models of GABAA receptor extracellular and transmembrane domains: important insights in pharmacology and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1291–1300. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar SJ, Whiting PJ, Bonnert TP, McKernan RM. Stoichiometry of a ligand-gated ion channel determined by fluorescence energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10100–10104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller SE, Brown CA, Nizza DT, Gawrisch K. Nuclear overhauser enhancement spectroscopy cross-relaxation rates and ethanol distribution across membranes. Biophys J. 2002;82:1396–1404. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75494-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Duprat F, Lesage F, Reyes R, Romey G, Heurteaux C, et al. Cloning, functional expression and brain localization of a novel unconventional outward rectifier K+ channel. EMBO J. 1996;15:6854–6862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Lesage F, Duprat F, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Fosset M, et al. A neuronal two P domain K+ channel stimulated by arachidonic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids. EMBO J. 1998;17:3297–3308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SA, Miller KW, Yellen G. A discrete site for general anesthetics on a postsynaptic receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks NP, Lieb WR. Do general anesthetics act by competitive binding to specific receptors? Nature. 1984;310:599–601. doi: 10.1038/310599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks NP. General anaesthesia: from molecular targets to neuronal pathways of sleep and arousal. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:370–386. doi: 10.1038/nrn2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks NP, Lieb WR. Volatile general anaesthetics activate a novel neuronal K+ current. Nature. 1988;333:662–664. doi: 10.1038/333662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks NP, Dickinson R, de Sousa SLM, Hall AC, Lieb WR. How does xenon produce anaesthesia. Nature. 1998;396:324. doi: 10.1038/24525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griepernau B, Böckmann RA. The influence of 1-alkanols and external pressure on the lateral pressure profiles of lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2008;95:5766–5778. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.142125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss M, Bushell TJ, Bright DP, Lieb WR, Mathie A, franks NP. Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide and cyclopropane. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:443–452. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales TG, Lambert JJ. The actions of propofol on inhibitory amino acid receptors of bovine adrenomedullary chromaffin cells and rodent central neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;104:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AC, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Stereoselective and non-stereoselective actions of isoflurane on the GABAA receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;112:906–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsey MJ. Effects of high pressure on the central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 1982;62:1341–1377. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.4.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsey MJ, Wardley-Smith B. Pressure reversal of narcosis produced by anaesthetics, narcotics and tranquillisers. Nature. 1975;257:811–813. doi: 10.1038/257811a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handford CA, Lynch JW, Baker E, Webb GC, Ford JH, Sutherland GR, et al. The human glycine receptor β-subunit: primary structure, functional characterisation and chromosomal localisation of the human and murine genes. Mol Brain Res. 1996;35:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B, Moody E, Skolnick P. Isoflurane anesthesia is stereoselective. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;217:215–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC, Adamo AIB. Effects of halothane and propofol on purified brain protein kinase C activation. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:147–155. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199407000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC, Akabas MH, Goldstein PA, Trudell JR, Orser BA, Harrison NL. Emerging molecular mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentschke H, Schwarz C, Antkowiak B. Neocortex is the major target of sedative concentrations of volatile anaesthetics: strong depression of firing rates and increase of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:93–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Guy N, Laigle C, Blondeau N, Duprat F, Mazzuca M, et al. TREK-1, a K+ channel involved in neuroprotection and general anesthesia. EMBO J. 2004;23:2684–2695. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann MW, Liu H-T, Hoenemann CW, Liu W-H, Durieux ME. Modulation of NMDA receptor function by ketamine and magnesium. Part II: interactions with volatile anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1182–1191. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200105000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homanics GE, Ferguson C, Quinlan JL, Daggett J, Snyder K, Lagenaur C, et al. Gene knockout of the α6 subunit of the γ-aminobutyric acid type a receptor: lack of effect on responses to ethanol, pentobarbital, and general anaesthetics. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:588–596. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horenstein J, Wagner DA, Czajkowski C, Akabas MH. Protein mobility and GABA-induced conformational changes in GABAA receptor pore-lining M2 segment. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:477–485. doi: 10.1038/87425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, Silva HMA, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain SS, Ziebell MR, Ruesch D, Hong F, Arevalo E, Kosterlitz JA, et al. 2-(3-Methyl-3H-diaziren-3-yl)ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-imidazole-5-carboxylate: a derivative of the stereoselective general anesthetic etomidate for photolabeling ligand-gated ion channels. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1257–1265. doi: 10.1021/jm020465v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irifune M, Katayama S, Takarada T, Shimizu Y, Endo C, Takata T, et al. MK-801 enhances gabaculine-induced loss of the righting reflex in mice, but not immobility. Can J Anesth. 2007;54:998–1005. doi: 10.1007/BF03016634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins A, Greenblatt EP, Faulkner HJ, Bertaccini E, Light A, Lin A, et al. Evidence for a common binding cavity for three general anesthetics within the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J, Andreasen A, Trudell JR, Harrison NL. Tryptophan scanning mutagensis in TM4 of the GABAA receptor α1 subunit: implications for modulation by inhaled anesthetics and ion channel structure. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:669–678. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtović-Todorović V, Todorović SM, Mennerick S, Powell S, Dirkranian K, Benshoff N, et al. Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is an NMDA antagonist, neuroprotectant and neurotoxin. Nat Med. 1995;4:460–463. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Zaitseva E, Schmidt M, Siebert F, Engelhard M, Schlesinger R, et al. Resolving voltage-dependent structural changes of a membrane photoreceptor by surface-enhanced IR difference spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12113–12117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802289105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson FH, Flagler EA. Hydrostatic pressure reversal of narcosis in tadpoles. Science. 1950;112:91–92. doi: 10.1126/science.112.2899.91-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson FH, Flagler EA. Activity of narcotized amphibian larvae under hydrostatic pressure. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1951;37:15–25. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030370103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MV, Harrison NL. Effect of volatile anesthetics on the kinetics of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1339–1349. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamo T, Nakano N, Kuroda Y, Handa T. Effects of an amphipathic α-helical peptide on lateral pressure and water penetration in phosphatidylcholine and monoolein mixed membranes. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24987–24992. doi: 10.1021/jp064988g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendig JJ, Cohen EN. Neuromuscular function at hyperbaric pressures: pressure–anesthetic interactions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1976;230:1244–1248. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.5.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendig JJ, Trudell JR, Cohen EN. Effects of pressure and anesthetics on conduction and synaptic transmission. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;195:216–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura A, Marszalec W, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Effects of halothane and propofol on excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in rat cortical neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:162–171. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koubi L, Tarek M, Bandyopadhyay S, Klein ML, Scharf D. Effects of the nonimmobilizer hexafluroethane on the model membrane dimyristoylphosphatidyl-choline. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:848–855. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Harrison NL. The actions of ether, alcohol and alkane general anaesthetics on GABAA and glycine receptors and the effects of TM2 and TM3 mutations. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:731–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Koltchine VV, Rick CE, Ye Q, Finn SE, Harrison NL. Propofol and other intravenous anesthetics have sites of action on the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor distinct from that for isoflurane. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:530–538. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Nishikawa K, Kikolaeva N, Lin A, Harrison NL. Methionine 286 in transmembrane domain 3 of the GABAA receptor β subunit controls a binding acvity for propofol and other alkylphenol general anesthetics. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:952–964. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00141-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laube B, Kuhse J, Betz H. Evidence for a tetrameric structure of recombinant NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2954–2961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02954.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Duprat F, Lazdunski M, Romey G, et al. A pH-sensitive yeast outward rectifier K+ channel with two pore domains and novel gating properties. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4183–4187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever MJ, Miller KW, Paton WDM, Smith EB. Pressure reversal of anaesthesia. Nature. 1971;231:368–371. doi: 10.1038/231368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G-D, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–11605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little HJ, Thomas DL. The effects of anaesthetics and high pressure on the responses of the rat superior cervical ganglion in vitro. J Physiol. 1986;374:387–399. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Au JD, Zou HL, Cotten JF, Yost CS. Potent activation of the human tandem pore domain K channel tresk with clinical concentrations of volatile anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1715–1722. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136849.07384.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Strzalka J, Tronin A, Johansson JS, Blaise JK. Mechanism of interaction between the general anesthetic halothane and a model ion channel protein, II: fluorescence and vibrational spectroscopy using a cyanophenylalanine probe. Biophys J. 2009;96:4176–4187. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lórenz-Fonfría VA, Granell M, León X, Leblanc G, Padros E. In-plane and out-of-plane infrared difference spectroscopy unravels tilting of helices and structural changes in a membrane protein upon substrate binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15094–15095. doi: 10.1021/ja906324z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Sleep, anesthesiology, and the neurobiology of arousal state control. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1268–1295. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysko GS, Robinson JL, Casto R, Ferrone RA. The stereospecific effects of isoflurane isomers in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90519-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Brandon NR, Cui T, Bondarenko V, Canlas C, Johansson JS, et al. Four-α-helix bundle with designed anesthetic binding pockets. Part I: structural and dynamical analyses. Biophys J. 2008;94:4454–4463. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Leung LS. Limbic system participates in mediating the effects of general anesthetics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1177–1192. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Shen B, Stewart LS, Herrick IA, Leung LS. The septohippocampal system participates in general anesthesia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-j0004.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DC, Plagenhoef M, Abraham J, Dennison RL, Aronstam RS. Volatile anesthetics and glutamate activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:809–817. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00519-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia MP, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Specific binding sites for alcohols and anesthetics on ligand-gated ion channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9305–9310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160128797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzenbach B, Maulet Y, Sefton L, Avner P, Guenet JL, Betz H. Structural analysis of mouse glycine receptor α-subunit genes. Identification and chromosomal localization of a novel variant, α4. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2607–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado J, Czajkowski C. Charged residues in the α1 and β2 pre-M1 regions involved in GABAA receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2031–2040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4555-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H. Welche Eigenschaft des Anaesthetica bedingt ihre narkotische Wirkung? Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie. 1899;42:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, et al. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KW, Paton WDM, Smith RA, Smith EB. The pressure reversal of general anesthesia and the critical volume hypothesis. Mol Pharmacol. 1973;9:131–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokrab Y, Bavro VN, Mizuguchi K, Martin IL, Todorov NP, Dunn SMJ, et al. Exploring ligand recognition and ion flow in comparative models of the human GABA type A receptor. J Mol Graph Model. 2007;26:760–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody EJ, Harris BD, Skolnick P. Stereospecific actions of the inhalation anesthetic isoflurane at the GABAA receptor complex. Brain Res. 1993;615:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91119-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody EJ, Knauer C, Granja R, Strakhova M, Skolnick P. Distinct loci mediate the direct and indirect actions of the anesthetic etomidate at GABAA receptors. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1310–1313. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins LJ. Some physical mechanisms in narcosis. Chem Rev. 1954;54:289–323. [Google Scholar]