Abstract

Oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) is a potent tumor suppressive mechanism that is thought to come at the cost of aging. The Forkhead Box O (FOXO) transcription factors are regulators of lifespan and tumor suppression. However, whether and how FOXOs function in OIS has been unclear. Here, we demonstrate a role for FOXO4 in mediating senescence by the human BRAFV600E oncogene which arises commonly in melanoma. BRAFV600E signaling through MEK resulted in increased ROS levels and JNK-mediated activation of FOXO4 via its phosphorylation on Thr223, Ser226, Thr447 and Thr451. BRAFV600E-induced FOXO4 phosphorylation resulted in p21cip1-mediated cell senescence independent of p16ink4a or p27kip1. Importantly, melanocyte-specific activation of BRAFV600E in vivo resulted in formation of skin nevi expressing Thr223/Ser226-phosphorylated FOXO4 and elevated p21cip1. Together, these findings support a model in which FOXOs mediate a trade-off between cancer and aging.

Introduction

Activating mutations in the Ser/Thr kinase BRAF are observed in ~7% of all human tumors with high occurrence in thyroid carcinoma, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer 1 and especially melanoma (~70%)2. The predominant BRAF mutation present in these cases is a substitution of Val600 for Glu (BRAFV600E), which causes increased downstream signaling towards MEK 2. Although BRAF-activating mutations initially stimulate proliferation, cell cycle progression is ultimately arrested through induction of senescence 3-5. OIS can be facilitated through the individual activities of p16ink4a and p21cip1 6,7 and also in case of BRAFV600E these cell cycle inhibitors are thought to regulate senescence 4,8,9.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) propagate cellular signaling induced by growth factors and thereby regulate a variety of cellular processes including proliferation 10,11. However, when ROS levels rise above a certain threshold, sometimes referred to as oxidative stress, ROS react with and damage the cellular interior. Additionally, excessive ROS can induce cellular senescence 12 and as such they are considered to accelerate aging and age-related pathologies13,14. ROS are known to signal to a plethora of downstream targets and it is currently elusive which of these regulate the induction of senescence.

FOXO transcription factors are the mammalian orthologs of the Caenorhabditis elegans protein DAF-16, which functions as an important determinant of lifespan 15. FOXOs were originally identified as downstream components of insulin/IGF signaling through phosphoinositide-3kinase (PI-3K) and protein kinase B (PKB/AKT) 16,17. In mice, FOXOs act as functionally redundant tumor suppressors 18, and in cell systems FOXOs can either mediate apoptosis or quiescence in response to growth factor deprivation 19. In contrast to insulin signaling, which represses FOXO activity, cellular ROS can activate FOXOs 20,21. Regulation of FOXOs by ROS occurs through numerous post-translational modifications 22, rendering FOXOs sensors of cellular ROS 23. Consequently, FOXO activation increases resistance to oxidative stress through transcription of enzymes as MnSOD 24 and Catalase 25 through a negative feedback loop. Increased FOXO activity is associated with longevity in model organisms 15 and humans 26 which lends credit to the hypothesis that excessive ROS accelerate aging. Thus, FOXOs are regulated by ROS and play a role in both tumor suppression and aging, and thereby provide an important paradigm to understanding the relation between aging and disease such as cancer.

Materials and methods

Additional information is available in the supplementary materials and methods

Antibodies

The antibodies against FOXO4 (834), HA (12CA5), phospho-Thr447 and phosphoThr451 have been described before21,27. The following antibodies were purchased: phosphoThr183/Tyr185-JNK and phosphoThr202/Tyr204-ERK (Cell Signaling), FOXO4-phospho-Thr28 (Upstate), MnSOD (Stressgen) trimethyl-H3K9 and FOXO3a (Upstate), p27kip1 and p21cip1 (BD pharmingen), p16ink4a (ab-2) (Neomarkers), p21cip1 (M19 and F5), BRAF (C19), FOXO4 (N19), FOXO1 (N18), PCNA (PC10) and p53 (DO-1) (Santa Cruz) and Tubulin (Sigma). Antibodies against phospho-Thr223 and Phospho-Tr223/Ser226 were generated by immunizing rabbits with the KLH-conjugated peptides CKAPKKKPSVLPAPPEGA-pT-PTSPVG and CKAPKKKPSVLPAPPEGA-pT-PT-pS-PVG, respectively, where pT and pS present phosphorylated Threonine and Serine. Produced antibodies were subjected to positive and negative affinity purification according to manufacturers protocol (Covance).

Constructs and RNAi

The following constructs have been described before: pbabe-puro, pMT2-HA-FOXO4, pRP261-GST-FOXO4-ΔDB16, 6xDBE-firefly luciferase, MnSOD-firefly luciferase and TK-renilla luciferase24, pEFm-BRAFV600E 2, p21cip1-luciferase28. pSuper-p21cip1 was a kind gift from Mathijs Voorhoeve29. A detailed explanation on the generation of HA-FOXO4-4A/E and pSuperior-shFOXO1/3 and 4 is available in the supplementary materials and methods. Smartpool oligo's against FOXO1,3a and 4, BRAF or scrambled oligo's (Dharmacon) were transfected at a final concentration of 100nM each (300nM for scrambled) using oligofectamine according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen).

Immunofluorescence, TUNEL staining and BrdU incorporation

Immunofluorescence was performed as described27, using antisera against FOXO4 (834 and mAb), HA (12CA5), PCNA, H3K9-Me(III) and pT223/S226. BrdU incorporation and TUNEL staining were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols (Roche). For the mouse sections anti-p21cip1 M19 and F5 were used.

Cellular ROS measurements with H2DCFDA

HEK293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3 or a plasmid encoding BRAFV600E (2μg), in parallel with pbabe-puro (500ng). 16hrs post-transfection cells were selected with 2μg/ml puromycin for 36hrs and subsequently left untreated or pretreated for 24hrs with 4mM NAC or 10μM U0126, washed with PBS and incubated for 10min with 1ml 10μM H2DCFDA (Invitrogen). Following recovery for 4 hours in medium with or without NAC or U0126. Cells were pretreated with or without 45min 200μM H2O2 and collected by trypsinization. Centrifugated cells were incubated with 0.02mg/ml Propidium Iodide (PI) and live were analyzed by FACS for DCF fluorescence. CHL and WM266.4 cells were treated similarly, but without puromycin and PI selection.

Colony Formation assay and SA-β-Gal staining

A14 or U2OS cells were transfected as indicated together with pbabe-puro (500ng). 24 hours post-transfection cells were subjected to puromycin selection (2μg/ml). Following 2.5 days of selection one set of cells was lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting for protein expression. 10 days post-transfection, cells were fixed in methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 25% methanol. Plates were dried and colony formation was quantified by destaining in 10% acetic acid and measuring optical density at 560nm. CHL, PMWK, Colo829 and A375 cells were treated similarly, but transfected with 500ng FOXO4 and 250ng pbabe-puro. SA-β-GAL staining was performed 9 days post-transfection as desribed30.

Results

Ectopic introduction of FOXO4 induces cellular senescence in BRAFV600E-expressing Colo829, A375 and SK-mel28 melanoma cells

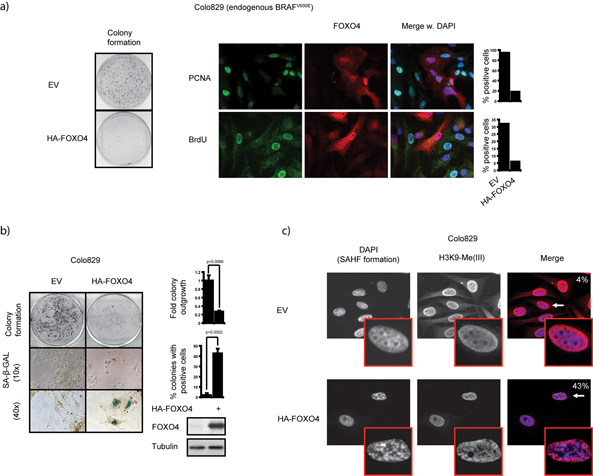

To study the involvement of FOXOs in BRAFV600E-dependent cellular responses we ectopically expressed FOXO4 in the human melanoma-derived cell line, Colo829, harboring an endogenous BRAFV600E mutation. This resulted in reduced colony formation along with diminished PCNA and BrdU positivity (Fig. 1a) but without significant TUNEL staining (Sup. fig. 1).

Figure 1. FOXO4 induces cellular senescence in endogenous BRAFV600E-expressing Colo829 and A375 cells.

a) Ectopic FOXO4 expression reduces proliferation of Colo829 cells. Colo829 cells transiently expressing HA-FOXO4 were subcultured in puromycin containing selection medium and stained for colony outgrowth. Additionally, a set of cells were stained at 2.5 days post transfection with anti-PCNA or analyzed for BrdU incorporation. 250 non-transfected and 50 transfected cells were quantified. Similar results were obtained in A375 melanoma cells. EV=Empty vector. b) Ectopic FOXO4 expression induces SA-β-GAL positivity in Colo829 cells. Colo829 cells expressing HA-FOXO4 were selected with puromycin and stained for colony formation, or SA-β-GAL. Protein samples were obtained at 2.5 days post transfection and analyzed by immunoblotting. 50 colonies were quantified for positive cells. c) FOXO4 expression in Colo829 cells induces senescence. Colo829 cells were transfected as in a) and at 5.5 days post transfection stained with DAPI to visualize Senescence Associated Heterochromatin Foci (SAHF) formation in parallel with anti-H3K9-Me(III) for H3K9-trimethylation. 100 cells were quantified and the percentage of double positive cells indicated.

FOXOs repress oxidative stress21 and increased oxidative stress is suggested to cause cellular senescence12. Surprisingly however, ectopic FOXO4 expression rendered Colo829 cells positive for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-GAL) activity (Fig. 1b). Also detection of two other independent markers of senescence 4,31, Senescence-Associated Heterochromatin Foci (SAHFs) and H3K9-trimethylation, was significantly enhanced by FOXO4 (Fig. 1c) suggesting this indeed is a senescence response .

To exclude artifacts of a single cell-type, we also expressed FOXO4 in other melanoma cell lines that express endogenous BRAFV600E, A375 and SK-Mel28, or wild type BRAF, CHL and PMWK. Whereas FOXO4 induced SA-B-GAL expression in A375 and SK-Mel28, no positivity was observed in CHL or PMWK cells (Sup. fig. 2 and data not shown). Thus, in endogenous BRAFV600E-expressing Colo829, A375 and SK-Mel28 melanoma cells expression of FOXO4 induces a growth arrest through cellular senescence.

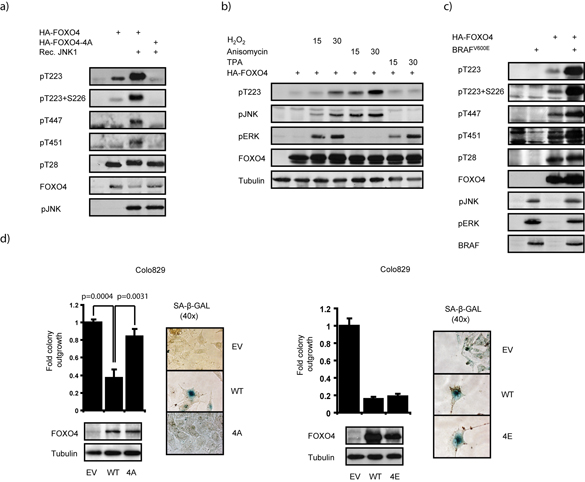

BRAFV600E induces phosphorylation of FOXO4 on JNK target sites

The MEK-ERK pathway is a primary signaling output for normal and oncogenic BRAF. In addition to MEK-ERK signaling, BRAFV600E expression is reported to promote activation of the c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) 32 which we confirmed (Sup. fig. 3). Previously, we demonstrated that FOXO4 is a JNK target, and identified Thr447 and Thr451 through mutation analysis as a subset of the phospho-acceptor sites 21. We therefore wondered whether BRAFV600E could signal through JNK towards FOXO4 to promote senescence. To fully address this question, we first determined all possible JNK sites of in vitro phosphorylated FOXO4 by LC-MS/MS mass-spectrometry analysis (supplementary data). In addition to the previously characterized Thr447 and Thr451, this revealed two novel residues, Thr223 and Ser226 (Sup. fig. 4). We generated phosphospecific antisera against these sites, including dually-phosphorylated Thr223/Ser226. In vitro phosphorylation by JNK significantly increased detection of wild type FOXO4 by these respective antisera, especially the newly discovered Thr223 and Ser226, whereas FOXO4-4A in which these residues are mutated to Ala (Fig. 2a) was not detected. This indicates that Thr223, Ser226, Thr447 and Thr451 are JNK phospho-acceptor sites.

Figure 2. FOXO4 is a downstream target of BRAFV600E through JNK-mediated phosphorylation.

a) Thr223, Ser226, Thr447 and Thr451 of FOXO4 are JNK sites in vitro. Phosphorylation status of immunoprecipitated HA-FOXO4 or HA-FOXO4-4A isolated from HEK293T cells was determined upon in vitro phosphorylation by recombinant JNK1. b) Phosphorylation of FOXO4 on Thr223 correlates with activation of JNK, not ERK. HEK293T cells transiently expressing HA-FOXO4 were treated with 200μM H2O2, 10μg/ml Anisomycin or 100ng/ml TPA and analysed for activation of ERK and JNK as well as FOXO4 phosphorylation on Thr223. c) BRAFV600E induces phosphorylation of FOXO4 on JNK sites. The phosphorylation of ectopically expressed FOXO4 in HEK293T cells was determined in the presence or absence of BRAFV600E. d) Mutation of the JNK sites to Ala, but not Glu, impairs senescence induction by FOXO4 in Colo829 cells. Colo829 cells were transfected with HA-FOXO4, HA-FOXO4-4A or HA-FOXO4-4E in which the JNK target sites Thr223, Ser226, Th447 and Thr451 are mutated to Ala (left panel) or Glu (right panel), respectively. Colony formation and SA-β-GAL assays were performed as in Fig. 1b.

Since BRAFV600E signaling induces activation of both ERK and JNK, we next determined whether phosphorylation of the identified sites in cultured cells is mediated by either of these kinases. H2O2, which activates both, indeed resulted in phosphorylation of Thr223 of FOXO4. Additionally, stimuli that exclusively activate either ERK (TPA and EGF) or JNK (anisomycin), showed that Thr223 phosphorylation correlates with activation of JNK, not ERK (Fig. 2b and Sup. fig. 5).

In agreement with JNK activation, BRAFV600E induced a significant increase in phosphorylation on all JNK sites, but not on the PKB/AKT site Thr28 (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, treatment of cells with the JNK inhibitor SP600125 not only inhibited BRAFV600E-induced JNK auto-phosphorylation in a dose dependent manner, but also Thr223 phosphorylation of FOXO4 (Sup. fig. 6). Together these results indicate that BRAFV600E promotes JNK-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO4.

To address whether phosphorylation of FOXO4 on the JNK sites is required for FOXO4 to be able to induce senescence in BRAFV600E-expressing melanoma cells we expressed the FOXO4-4A mutant next to wild type FOXO4. FOXO4-4A neither significantly repressed colony formation nor induced SA-B-GAL positivity (Fig. 2d). In contrast, a mutant of FOXO4 that mimics phosphorylation on JNK sites, FOXO4-4E, induced a senescence response similar to wild type FOXO4 (Fig. 2d). Altogether, these data indicate that FOXO4 is a downstream target of BRAFV600E through JNK-mediated phosphorylation and that phosphorylation on the JNK-target sites is required for FOXO4 to promote senescence in response to BRAFV600E.

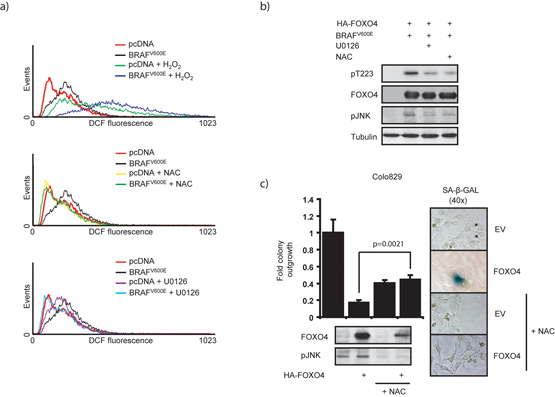

BRAFV600E signaling elevates cellular ROS levels, which promote FOXO4 phosphorylation by JNK

JNK activity is regulated through a large variety of signaling pathways and we therefore next addressed the molecular mechanism through which BRAFV600E regulates JNK and thereby FOXO4 activity. Elevations in cellular ROS generated through H2O2-treatment of cells can directly invoke senescence 12 and senescence induction in for instance melanocytes has recently been correlated with increased ROS 33. Moreover, OIS can be bypassed by ROS scavenging compounds such as N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) 34,35. Hence, we investigated the possibility that BRAFV600E signaling affects cellular ROS levels by loading cells with the ROS detecting probe H2DCFDA (DCF). BRAFV600E expression significantly increased cellular ROS levels as detected by DCF fluorescence (Fig. 3a). The BRAFV600E-induced rise in cellular ROS could be further increased by treatment with H2O2 (45 minutes 200μM), but was impaired upon pre-incubation with NAC. Downstream signaling through MEK appears at least partially required, since pre-incubation with the MEK inhibitor U0126 reduced DCF fluorescence. These data indicate that ectopic BRAFV600E expression leads to the generation of cellular ROS through downstream MEK signaling. In agreement herewith, melanoma cells expressing BRAFV600E showed higher basal ROS levels compared to wild type BRAF-expressing cells (Sup. fig. 7). Elevations in ROS are sufficient for phosphorylation of FOXO4 by JNK, as treatment of cells with H2O2 resulted in a time-dependent increase of both JNK activation and Thr223 phosphorylation (Sup. fig. 8 and Fig. 2b). Moreover, BRAFV600E-mediated JNK activation and FOXO4 phosphorylation were repressed upon pretreatment of cells with NAC or U0126 (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. MEK-dependent BRAFV600E signaling elevates cellular ROS levels, which stimulate Thr223 phosphorylation of FOXO4 by JNK.

a) BRAFV600E expression increases cellular ROS. BRAFV600E-expressing HEK293T cells were treated 24 hours with 4mM NAC, 20μM U0126 or 45 minutes with 200μM H2O2 and analyzed for DCF fluorescence. b) Reduced MEK activity or cellular ROS inhibits BRAFV600E-induced FOXO4 phosphorylation by JNK. Experiment as in Fig. 2c, but upon pretreatment for 24hrs 20μM U0126 or 4mM NAC. c) Interference with cellular ROS levels inhibits FOXO4-induced senescence. Colo829 cells were transfected as in Fig. 1b and treated at days 1.5 and 5.5 post transfection with 1mM NAC and analyzed for colony formation and SA-β-GAL positivity.

Prolonged treatment with U0126 induces apoptosis in Colo829 cells 36, making it impossible to interpret the effect of this inhibitor on FOXO4-induced senescence. Therefore, Colo829 cells were treated with NAC to reduce cellular ROS. This resulted in reduced colony formation of Colo829 cells (Fig. 3c) most likely due to the fact that proliferation per se requires low amounts of ROS 14. Importantly however, NAC impaired the ability of FOXO4 to induce senescence in these cells. Altogether, these data point to a pathway in which BRAFV600E induces FOXO4 phosphorylation by JNK through a MEK-regulated elevation of intracellular ROS and in line with that that ROS are essential for FOXO4 to induce senescence in the presence of BRAFV600E.

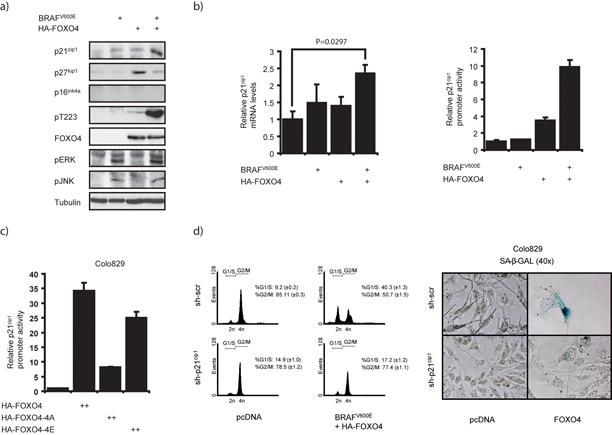

p21cip1 mediates the cell cycle arrest and senescence response by BRAFV600E-FOXO4 signaling

Next, we addressed the mechanism downstream of how FOXO4 promotes BRAFV600E-induced senescence. p27kip1 is an important mediator of FOXO-induced G1-arrest and subsequent quiescence response in the absence of growth factors 19. Therefore, we reasoned a role for p27kip1. FOXO4-induced p27kip1 expression, however, was counteracted rather than enhanced by co-expression of BRAFV600E (Fig. 4a and data not shown). Thus, we conclude that the FOXO4-mediated cell cycle arrest in response to BRAFV600E signaling is unlikely to be regulated through p27kip1.

Figure 4. BRAFV600E-FOXO4 signaling induces transcription of p21cip1, not p27kip1 or p16ink4a.

a) BRAFV600E and HA-FOXO4 co-expression results in increased p21cip1. Total lysates of puromycin selected HEK293T cells expressing HA-FOXO4 and BRAFV600E were analyzed by immunoblotting. b) BRAFV600E and FOXO4 co-operatively promote p21cip1 transcription. Quantitative real-time PCR for p21cip1 mRNA in HEK293T (left panel) and p21cip1-luciferase assay on A14 cell lysates (right panel), which transiently expressed HA-FOXO4 and BRAFV600E. c) Mutation of the JNK-sites in FOXO4 affects the ability to transactivate p21cip1 transcription. p21cip1-luciferase assay in Colo829 cells, using wild type FOXO4, HA-FOXO4-4A and HA-FOXO4-4E. d) p21cip1 is required for FOXO-mediated G1-arrest and senescence response in a background of BRAFV600E signaling. (Left panel) U2OS cells (optimal for FOXO-mediated G1-arrest19), were transfected with BRAFV600E and HA-FOXO4 in combination with a plasmid encoding a short hairpin against p21cip1 or a scrambled control. (Right panel) SA-β-GAL staining after expression of HA-FOXO4 in combination with a plasmid encoding a scrambled or p21cip1 short hairpin in Colo829.

Next, we addressed the importance of another CDK inhibitor, p16ink4a, which has been implicated in senescence. p16ink4a levels do not appear to increase upon FOXO4 and BRAFV600E co-expression (Fig. 4a and data not shown). Also, in Colo829 cells in which FOXO4 induces senescence (Fig. 1), a premature stop mutation is present in the CDKN2A gene resulting in loss of p16ink4a expression 37. These data also argue against involvement of p16ink4a in FOXO4-mediated OIS driven by BRAFV600E.

Since p21cip1 and p16ink4a appear functionally redundant in OIS 6,7,9, we next analyzed a role for p21cip1. Interestingly, BRAFV600E cooperated with FOXO4 to induce p21cip1 expression (Fig. 4a) and in correlation with the induction of senescence, FOXO4 expression increased p21cip1 expression in Colo829 cells (Sup. fig. 9). Similar effects were observed on p21cip1 mRNA expression determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Moreover BRAFV600E and FOXO4 expression resulted in a synergistic activation of a luciferase-reporter gene driven by the p21cip1 promoter (Fig. 4b). This level of synergy was also observed using a construct under a different FOXO responsive promoter (i.e. MnSOD) and a synthetic promoter encompassing 6 optimal FOXO DNA binding elements (6xDBE, Sup. fig. 10), suggesting that the co-operative induction indeed reflects increased FOXO activity.

As HA-FOXO4-4A did not induce senescence in Colo829 cells, whereas HA-FOXO4-4E did, we also determined the ability of these mutants to induce p21cip1 transcription. In line with the lack of senescence induction, HA-FOXO4-4A, but not HA-FOXO4-4E, was significantly less capable of driving p21cip1 transcription (Fig. 4c). These data indicate that BRAFV600E activates FOXO4 through JNK-mediated phosphorylation to promote p21cip1 transcription, which in Colo829 cells correlates with the induction of senescence.

To address to what extent p21cip1 is required for the FOXO4-induced cell cycle arrest and senescence in response to BRAFV600E signaling we used shRNA- mediated knockdown of p21cip1. This impaired p21cip1 expression induced by BRAFV600E FOXO4 co-expression (Sup. fig. 11). Whereas BRAFV600E and FOXO4 together induced a strong G1-arrest as determined by FACS analysis, this effect was abolished upon knockdown of p21cip1 (Fig. 4d). Since p21cip1 expression is elevated in FOXO4-induced senescence in Colo829 cells, we also addressed the effect of p21cip1 knock-down on the induction of senescence. Strikingly, FOXO4 expression did not induce SA-βGAL staining in Colo829 cells upon p21cip1 knockdown (Fig. 4d), indicating that p21cip1 is required FOXO4-induced senescence in these cells. Altogether, these data show that FOXO4 is a downstream target of BRAFV600E that can facilitate a cell cycle arrest and OIS through regulation of p21cip1.

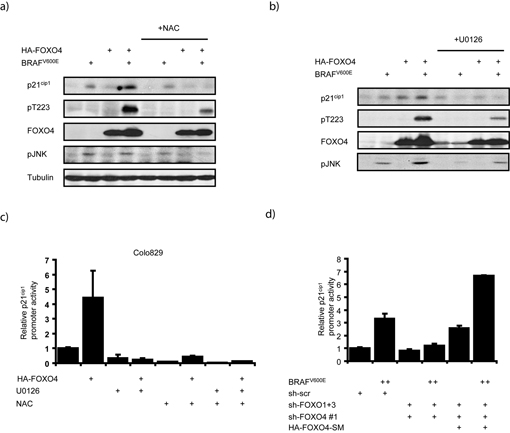

BRAFV600E regulates p21cip1 expression through MEK and ROS-dependent phosphorylation of FOXOs

Following our observations that suggest BRAFV600E-mediated JNK/FOXO4 activation runs through MEK-ROS signaling, we addressed the involvement of MEK and ROS in the regulation of p21cip1 and cell cycle arrest by BRAFV600E and FOXO4. Pretreatment of cells with either NAC, to reduce ROS (Fig. 5a), or U0126, to inhibit MEK (Fig. 5b), repressed JNK activation by BRAFV600E, phosphorylation of FOXO4 on the JNK target site Thr223 and the co-operative induction of p21cip1. Furthermore, whereas ectopic expression of FOXO4 in Colo829 cells significantly enhanced p21cip1 promoter activity, pretreatment of these cells with U0126 or NAC reduced this effect (Fig. 5c). This shows that JNK-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO4 and the concomitant activation of p21cip1 transcription are dependent on MEK activity and elevations in cellular ROS.

Figure 5. BRAFV600E regulates p21cip1 expression through MEK-ROS-JNK signaling towards endogenous FOXO4.

a) Scavenging of cellular ROS represses JNK activation, Thr223-FOXO4 phosphorylation and subsequent p21cip1 expression. Lysates of puromycin selected, untreated or NAC-treated (4mM, 24hrs) HEK293T cells were analyzed by immunoblotting. Cells were transfected and treated as in Fig. 3a and. b) Interference with MEK signaling represses JNK activation, Thr223-FOXO4 phosphorylation and subsequent p21cip1 expression. Experiment as in a), except with pretreatment for 24hrs with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (20μM). c) FOXO4-induced p21cip1 transcription in Colo829 cells requires MEK activity and cellular ROS. p21cip1-luciferase assay from lysates of Colo829 cells expressing HA-FOXO4 following 24hrs pretreatment with 10μM U0126 or 4mM NAC. d) Endogenous FOXOs mediate BRAFV600E-induced p21cip1 transcription. A14 cells expressing BRAFV600E, short hairpins against FOXO1+3a and FOXO4 or a scrambled sequence and a FOXO4-mutant, insensitive to its corresponding short hairpin (HA-FOXO4-SM) were subjected to a p21cip1-luciferase assay. High levels of BRAFV600E were transfected (2μg (++) compared to 200ng otherwise used throughout the study to force higher p21cip1 transcription.

Next, we investigated the role of endogenous FOXOs in signaling from BRAFV600E towards p21cip1 transcription. High ectopic expression of BRAFV600E strongly induced p21cip1 promoter activity (8 and Fig. 5d). This induction was abrogated upon shRNA-mediated simultaneous depletion of endogenous FOXO1, 3a and 4, while add-back of a FOXO4 mutant insensitive to shRNA-mediated knockdown (FOXO4-SM) was sufficient to rescue BRAFV600E-induced transactivation of the p21cip1 promoter (Fig. 5d and sup. fig. 12+13). Thus, endogenous FOXOs are essential for ectopic BRAFV600E to induce p21cip1 transcription.

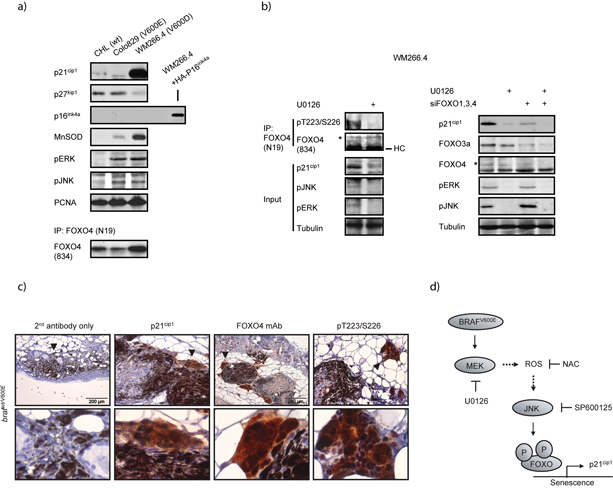

Endogenous BRAFV600E regulates FOXO4 phosphorylation and p21cip1 expression in cultured melanoma cells and in vivo

To further investigate the endogenous regulation of FOXO4 by oncogenic BRAF, we employed a distinct human melanoma-derived cell line WM266.4 (BRAFV600D; Fig. 6a). WM266.4 cells are tumorigenic yet express very high levels of p21cip1. This, we reasoned, made them suitable to investigate the entire endogenous signaling cascade from oncogenic BRAF towards p21cip1. Like Colo829 and in agreement with hyperactive BRAF signaling, WM266.4 cells expressed a significant amount of active ERK and JNK. As for Colo829 cells, expression of p16ink4a was not detectable in this cell line (Fig 6a and 38). siRNA-mediated knockdown of BRAF in WM226.4 cells reduced ERK and JNK activity and, importantly, resulted in diminished p21cip1 expression (Sup. fig. 14) arguing that the high p21cip1 level in WM266.4 cells is indeed driven by the oncogenic BRAF. Treatment of WM266.4 cells with U0126 inhibited MEK activity and subsequent JNK activation, indicating that indeed also in these cells MEK signaling is essential for JNK activation by oncogenic BRAF (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, next to impaired p21cip1 expression the U0126-mediated repression of JNK reduced phosphorylation of endogenous FOXO4 on the JNK sites Thr223+Ser226 and also siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous FOXOs reduced the p21cip1 expression (Fig. 6b). U0126 further enhanced this reduction, probably reflecting incomplete knockdown of FOXOs by these siRNAs. Together, these experiments indicate that oncogenic BRAF can regulate p21cip1 expression through phosphorylation of endogenous FOXOs by JNK, confirming the results we obtained in our overexpression studies.

Figure 6. Endogenous BRAFV600E regulates p21cip1 transcription through FOXO4 phosphorylation on the JNK target sites.

a) Characterization of WM266.4 (BRAFV600D) cells. CHL (wt BRAF), Colo829 (BRAFV600E) and WM266.4 (BRAFV600D) cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting. Endogenous FOXO4 expression was determined after immunoprecipitation. b) (Left panel) U0126 abrogates JNK signaling, endogenous phosphorylation of FOXO4 on Thr223+Ser226 and p21cip1 expression in WM266.4 cells. WM266.4 cells were untreated or treated for 24hrs with 10μM U0126 and analyzed as in a). The phosphorylation status of endogenous FOXO4 was determined after immunoprecipitation. HC=Heavy Chain. (Right panel) Endogenous FOXOs regulate p21cip1 expression in WM266.4 cells. Lysates of WM266.4 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or siRNA against FOXO1,3a and 4 (siFOXO) and untreated or treated for 24 hrs with 20μM U0126 were analyzed by immunoblotting. d) Expression of p21cip1, total FOXO4 and Thr223/Ser226-phosphorylated FOXO4 is elevated in neoplastic regions of BRAFV600E-induced nevi. Top panels: Skin sections of tamoxifen treated Braf+/LSL-V600E; Tyr::CreERT2+/o mice were analyzed for background signal (2nd antibody only), p21cip1 expression, total FOXO4 and Thr223/Ser226 phosphorylated FOXO4. Higher magnifications of the nevus (arrowheads) are shown in the lower panels. The top right panel shows undifferentiated nevi. Lower right panel represents a magnification of epidermal staining from bottom left panel. Untreated tissue did not typically show positive staining. e) Model on the regulation of FOXO4 by BRAFV600E, resulting in p21cip1-mediated senescence. BRAFV600E signaling activates MEK. This in turn, induces elevations in cellular ROS levels, thereby promoting activation of JNK. JNK subsequently phosphorylates FOXO4 and thereby promotes specific transcription of p21cip1, rather than p27kip1 or p16ink4a, and triggers a senescence response.

Ultimately, to study the biological relevance of our observations in vivo, we employed a Braf+/LSL-V600E; Tyr::CreERT2+/o mouse model, which expresses BRAFV600E in melanocytes off the endogenous Braf gene in a tamoxifen inducible manner 39. As reported before, activation of BRAFV600E-signaling induced melanocytic nevi within the dermis, composed of nests of pigmented epitheloid cells intermingled with whorls of lightly pigmented and amelanotic spindle cells (Sup. fig 15). At the periphery of these melanocytic nevi, we observed multiple patches of darkly pigmented, large polygonal cells, interpreted as neoplastic melanocytes. p21cip1 expression was significantly expressed within these neoplastic melanocytes at the periphery of the BRAFV600E-induced nevi (Fig. 6c), and minor p21cip1 expression was detected in the less pigmented regions of the nevi and within epidermal layers. To investigate endogenous FOXO4 expression in the mouse skin, we developed novel monoclonal antisera. The antisera could immunostain ectopically expressed mouse HA-FOXO4 in Colo829 cells (Sup. fig. 16). When applied to the mouse skin sections, the antisera showed expression of endogenous FOXO4 in the mouse skin (Fig. 6c). To determine the phosphorylation status of FOXO4 on the JNK target sites in the BRAFV600E-expressing skin samples, we used pT223/S226 antiserum. Detection with the phospho-Thr223/Ser226 antisera showed nuclear staining in unstimulated cells, including Colo829 (Sup. fig. 17 and data not shown). Knockdown of endogenous FOXO4 reduced, although not abolished, the signal, demonstrating the extent of specificity of this antisera for endogenous FOXO4. Importantly, endogenous Thr223/Ser226 phosphorylation of FOXO4 was specifically enriched in the areas of the nevi that also showed p21cip1 staining (Fig. 6c). Thus, in line with the cell culture data, in vivo activation of oncogenic BRAF promotes nevi formation, i.e. senescence in vivo, which harbor phosphorylation of FOXO4 on the JNK target sites Thr223/Ser226, and elevated p21cip1 expression within similar compartments.

Discussion

Here, we describe a role for FOXO4 in BRAFV600E-induced senescence. BRAFV600E activates FOXO4 through a MEK-ROS-JNK signaling cascade to induce p21cip1 expression and senescence (Fig. 6d). Senescence represents a barrier for tumor formation and consequently the melanoma-derived cells we have employed de facto have bypassed this barrier. Irrespective, in cell culture active FOXO re-imposes this barrier, suggesting that FOXO inactivation is one of the requirements for senescence bypass. This conclusion is supported by data showing that in mice loss of PTEN and consequently reduced FOXO activity, synergizes with BRAFV600E to induce melanoma 40. Despite limitations in studying senescence in melanoma cell lines in culture, our histochemical analysis of lesions from BRAFV600E mice clearly suggests that in vivo FOXO and p21cip1 indeed function in the senescence response induced by BRAFV600E.

Oncogenes induce senescence through various mechanisms. Although HRAS is an upstream regulator of RAF, HRASG12V expression in primary melanocytes induces senescence through the ER-associated unfolded protein response, whereas oncogenic (B)RAF does not 32. This difference between RAS and RAF is also reflected in mice models in which BRAFV600E induces both melanocyte senescence and melanoma 39, whereas HRASG12V, but not NRASQ61K, induces senescence and only melanoma if combined with loss of tumor suppressors p16ink4a or p19Arf 41. Interestingly, senescence in general, including melanocyte senescence 33, frequently correlates with elevated levels of ROS and OIS can be bypassed by ROS scavenging compounds 34,35. BRAFV600E chronically increases cellular ROS, which ,as we showed, is required for activation of FOXO4 ,p21cip1 transcription and subsequent senescence. Together, these and our data suggest that besides oncogene-specific pathways, increased ROS directs part of the senescence program which may be more generic. Recently, RAS-induced senescence was shown to require a RAS-dependent negative feedback loop repressing PI3K-PKB/AKT activity 42 As ROS, reduced PKB/AKT activity also activates FOXO suggesting activation of FOXO is the general event in senescence rather than the ROS/JNK signaling mechanism. Interestingly, the idea that FOXO activation will be a general component of senescence onset is in agreement with the current notion that the reverse, i.e. FOXO inactivation, represents a general component of tumor onset 18.

Mechanisms of senescence induction, also greatly differ between cell types. In cell culture, melanocyte senescence differs from fibroblast senescence (discussed in43). Human melanocytes deficient for INK4a show an impaired senescence response but INK4a-deficient human fibroblasts senesce normally. Since a number of families with inherited predisposition to melanoma showed loss of p16ink4a 44,45, these and other data suggest that INK4a-dependent senescence is especially important in melanocytes. However, loss of p16ink4a is not very common in early stage melanomas 46,and in oncogenic BRAF-positive human and mouse nevi, examples of cellular senescence in vivo, p16ink4a expression is mosaic 47,48. Also, recently we showed in the Braf+/LSL-V600E; Tyr::CreERT2+/o mouse model, that loss of p16ink4a does not affect BRAFV600E-induced nevus formation 39. Furthermore in these mice BRAFV600E-induced melanoma showed nuclear p16ink4a staining in agreement with clinical data showing significant nuclear p16ink4a expression in primary melanoma (30%-85%) as well as metastatic melanoma (15%)48. Thus, although p16ink4a fulfills an important role in the suppression of melanoma progression, it appears not to be essential for establishing senescence (See also 4). Here we show firstly, that in the absence of p16ink4a FOXO4 can induce senescence and second, this requires p21cip1. This confirms earlier suggestion that p21cip1 may facilitate melanocyte senescence in the absence of p16ink4a 5. Thus, in BRAFV600E signaling, p21cip1 and p16ink4a appear to regulate two independent cell cycle inhibitory responses that are functionally redundant to the induction of BRAFV600E-induced senescence.

Besides INK4a, the requirement for FOXO further defines differences between fibroblasts and melanocytes in senescence induction. In contrast to our observations with respect to OIS in melanoma cells and melanocytes in vivo, in fibroblasts loss of FOXO3a rather than activation of FOXO has been implicated in replicative senescence 49. Recently, a differential requirement for FOXO has been suggested in tumor progression50 and it will be of interest to see whether a similar differential requirement applies to the various stages at which cellular senescence can be induced.

FOXOs function as tumor suppressors 18, and senescence induction by FOXO as shown here provides one mechanism for this function of FOXO. Importantly, although a mechanism of tumor suppression, it is argued that cellular senescence is also causative to organismal aging 51,52. OIS may therefore represent a trade-off between tumor suppression and lifespan. Interestingly, both lack of growth factor signaling and increased ROS result in FOXO activation. However, the absence of growth factor signaling can impose a reversible p27kip1-mediated G1 cell cycle arrest and/or quiescence, which may be used to repair for example cellular damage 24. In this manner FOXO may positively affect lifespan and importantly with little cost to the organism. However, in response to BRAFV600E-induced ROS, FOXOs protect against tumorigenesis, through induction of senescence and unlike the former, this protection is not without cost. Our findings underline the pivotal role that FOXOs play in mediating the role of ROS in normal signaling as well as aging and it will be of interest to see whether for example age in return affects the ability of FOXO to mediate senescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from The Netherlands Science Organization (NWO, Vici), The Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding), The Center for Biomedical Genetics (CBG) and The Cancer Genomics Center (CGC).

Reference List

- 1.Garnett MJ, Marais R. Guilty as charged: B-RAF is a human oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J, Hargrave D, Pritchard-Jones K, Maitland N, Chenevix-Trench G, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Palmieri G, Cossu A, Flanagan A, Nicholson A, Ho JW, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Weber BL, Seigler HF, Darrow TL, Paterson H, Marais R, Marshall CJ, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Futreal PA. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wellbrock C, Karasarides M, Marais R. The RAF proteins take centre stage. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2004;5:875–885. doi: 10.1038/nrm1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CM, Majoor DM, Shay JW, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray-Schopfer VC, Cheong SC, Chong H, Chow J, Moss T, bdel-Malek ZA, Marais R, Wynford-Thomas D, Bennett DC. Cellular senescence in naevi and immortalisation in melanoma: a role for p16? Br.J.Cancer. 2006;95:496–505. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chudnovsky Y, Adams AE, Robbins PB, Lin Q, Khavari PA. Use of human tissue to assess the oncogenic activity of melanoma-associated mutations. Nat.Genet. 2005;37:745–749. doi: 10.1038/ng1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quereda V, Martinalbo J, Dubus P, Carnero A, Malumbres M. Genetic cooperation between p21Cip1 and INK4 inhibitors in cellular senescence and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2007;26:7665–7674. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woods D, Parry D, Cherwinski H, Bosch E, Lees E, McMahon M. Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol.Cell Biol. 1997;17:5598–5611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu J, Woods D, McMahon M, Bishop JM. Senescence of human fibroblasts induced by oncogenic Raf. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkel T. Redox-dependent signal transduction. FEBS Lett. 2000;476:52–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01669-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone JR, Yang S. Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxid.Redox.Signal. 2006;8:243–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen QM, Bartholomew JC, Campisi J, Acosta M, Reagan JD, Ames BN. Molecular analysis of H2O2-induced senescent-like growth arrest in normal human fibroblasts: p53 and Rb control G1 arrest but not cell replication. Biochem.J. 1998;332(Pt 1):43–50. doi: 10.1042/bj3320043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J.Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG. Hydrogen peroxide: a metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2007;8:722–728. doi: 10.1038/nrm2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kops GJ, de Ruiter ND, de Vries-Smits AM, Powell DR, Bos JL, Burgering BM. Direct control of the Forkhead transcription factor AFX by protein kinase B. Nature. 1999;398:630–634. doi: 10.1038/19328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y, Ding Z, Miao L, Tothova Z, Horner JW, Carrasco DR, Jiang S, Gilliland DG, Chin L, Wong WH, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, Alt FW, Greenberg ME. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Essers MA, Weijzen S, Vries-Smits AM, Saarloos I, de Ruiter ND, Bos JL, Burgering BM. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 2004;23:4802–4812. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Horst A, Burgering BM. Stressing the role of FoxO proteins in lifespan and disease. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2007;8:440–450. doi: 10.1038/nrm2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dansen TB, Smits LM, van Triest MH, de Keizer PL, van, L. D, Koerkamp MG, Szypowska A, Meppelink A, Brenkman AB, Yodoi J, Holstege FC, Burgering BM. Redox-sensitive cysteines bridge p300/CBP-mediated acetylation and FoxO4 activity. Nat.Chem.Biol. 2009;5:664–672. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kops GJ, Dansen TB, Polderman PE, Saarloos I, Wirtz KW, Coffer PJ, Huang TT, Bos JL, Medema RH, Burgering BM. Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature. 2002;419:316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature01036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science. 2002;295:2450–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willcox BJ, Donlon TA, He Q, Chen R, Grove JS, Yano K, Masaki KH, Willcox DC, Rodriguez B, Curb JD. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2008;105:13987–13992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brenkman AB, de Keizer PL, van den Broek NJ, van der, G. P, van Diest PJ, van der, H. A, Smits AM, Burgering BM. The peptidyl-isomerase Pin1 regulates p27kip1 expression through inhibition of Forkhead box O tumor suppressors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7597–7605. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duursma A, Agami R. p53-Dependent regulation of Cdc6 protein stability controls cellular proliferation. Mol.Cell Biol. 2005;25:6937–6947. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6937-6947.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collado M, Serrano M. The power and the promise of oncogene-induced senescence markers. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2006;6:472–476. doi: 10.1038/nrc1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denoyelle C, Abou-Rjaily G, Bezrookove V, Verhaegen M, Johnson TM, Fullen DR, Pointer JN, Gruber SB, Su LD, Nikiforov MA, Kaufman RJ, Bastian BC, Soengas MS. Anti-oncogenic role of the endoplasmic reticulum differentially activated by mutations in the MAPK pathway. Nat.Cell Biol. 2006;8:1053–1063. doi: 10.1038/ncb1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leikam C, Hufnagel A, Schartl M, Meierjohann S. Oncogene activation in melanocytes links reactive oxygen to multinucleated phenotype and senescence. Oncogene. 2008;27:7070–7082. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee AC, Fenster BE, Ito H, Takeda K, Bae NS, Hirai T, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Howard BH, Finkel T. Ras proteins induce senescence by altering the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species. J.Biol.Chem. 1999;274:7936–7940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vafa O, Wade M, Kern S, Beeche M, Pandita TK, Hampton GM, Wahl GM. c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability. Mol.Cell. 2002;9:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray-Schopfer VC, Karasarides M, Hayward R, Marais R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocks apoptosis in melanoma cells when BRAF signaling is inhibited. Cancer Res. 2007;67:122–129. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wellbrock C, Rana S, Paterson H, Pickersgill H, Brummelkamp T, Marais R. Oncogenic BRAF regulates melanoma proliferation through the lineage specific factor MITF. PLoS.ONE. 2008;3:e2734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wellbrock C, Marais R. Elevated expression of MITF counteracts B-RAF-stimulated melanocyte and melanoma cell proliferation. J.Cell Biol. 2005;170:703–708. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhomen N, Reis-Filho JS, da Rocha DS, Hayward R, Savage K, Delmas V, Larue L, Pritchard C, Marais R. Oncogenic Braf induces melanocyte senescence and melanoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dankort D, Curley DP, Cartlidge RA, Nelson B, Karnezis AN, Damsky WE, Jr., You MJ, DePinho RA, McMahon M, Bosenberg M. Braf(V600E) cooperates with Pten loss to induce metastatic melanoma. Nat.Genet. 2009;41:544–552. doi: 10.1038/ng.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ackermann J, Frutschi M, Kaloulis K, McKee T, Trumpp A, Beermann F. Metastasizing melanoma formation caused by expression of activated N-RasQ61K on an INK4a-deficient background. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4005–4011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Courtois-Cox S, Genther Williams SM, Reczek EE, Johnson BW, McGillicuddy LT, Johannessen CM, Hollstein PE, MacCollin M, Cichowski K. A negative feedback signaling network underlies oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ha L, Merlino G, Sviderskaya EV. Melanomagenesis: overcoming the barrier of melanocyte senescence. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1944–1948. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.13.6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gruis NA, van, d. V, Sandkuijl LA, Prins DE, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Kamb A, Bergman W, Frants RR. Homozygotes for CDKN2 (p16) germline mutation in Dutch familial melanoma kindreds. Nat.Genet. 1995;10:351–353. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ranade K, Hussussian CJ, Sikorski RS, Varmus HE, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D, Dracopoli NC. Mutations associated with familial melanoma impair p16INK4 function. Nat.Genet. 1995;10:114–116. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li W, Sanki A, Karim RZ, Thompson JF, Soon LC, Zhuang L, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. The role of cell cycle regulatory proteins in the pathogenesis of melanoma. Pathology. 2006;38:287–301. doi: 10.1080/00313020600817951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Hostetter G, Wagner U, Kakareka J, Salem G, Pohida T, Heenan P, Duray P, Kallioniemi O, Hayward NK, Trent JM, Meltzer PS. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat.Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van, D. R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nogueira V, Park Y, Chen CC, Xu PZ, Chen ML, Tonic I, Unterman T, Hay N. Akt determines replicative senescence and oxidative or oncogenic premature senescence and sensitizes cells to oxidative apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:458–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hedrick SM. The cunning little vixen: Foxo and the cycle of life and death. Nat.Immunol. 2009;10:1057–1063. doi: 10.1038/ni.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campisi J, d'Adda d. F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collado M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 2007;130:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.