Abstract

The cytokine MIF is involved in inflammation and cell proliferation via pathways initiated by its binding to the transmembrane receptor CD74. MIF also promotes AMPK activation with potential benefits for response to myocardial infarction and ischaemia-reperfusion. Structure-based molecular design has led to the discovery of not only antagonists, but also the first agonists of MIF-CD74 binding. The compounds contain a triazole core that is readily assembled via Cu-catalyzed click chemistry. The agonist and antagonist behaviors were confirmed via study of MIF-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation in human fibroblasts.

Keywords: MIF, cytokine, agonists, structure-based design, AMPK activation, ERK phosphorylation, click chemistry

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a pleiotropic cytokine that is expressed in multiple cell types including macrophages, endothelial cells, T-cells, and cardiomyocytes. It is involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases as well as in tumor growth and angiogenesis. The potential biomedical significance of MIF regulation is under active investigation.1–3 MIF signal transduction is initiated by binding to a receptor complex consisting of CD74 and CD44.4–6 Though emphasis has been placed on discovery of antagonists of MIF signaling,1–3 report of agonists would be valuable both as probes of MIF biology and in therapeutic indications. For example, MIF activation leads to an immune adjuvant effect.7 Furthermore, it has recently been shown that MIF stimulates the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in heart muscle.8 AMPK plays a central role in cardiac response to ischaemia through promoting glucose uptake and limiting myocardial injury and apoptosis.9 Since AMPK deficiency is deleterious during ischaemia-reperfusion, MIF-CD74 agonism also provides a potential therapy for acute myocardial ischaemia via enhanced AMPK activation.8 Enhancement of MIF signaling and AMPK activity in limiting cardiac damage may be especially beneficial for older patients.10

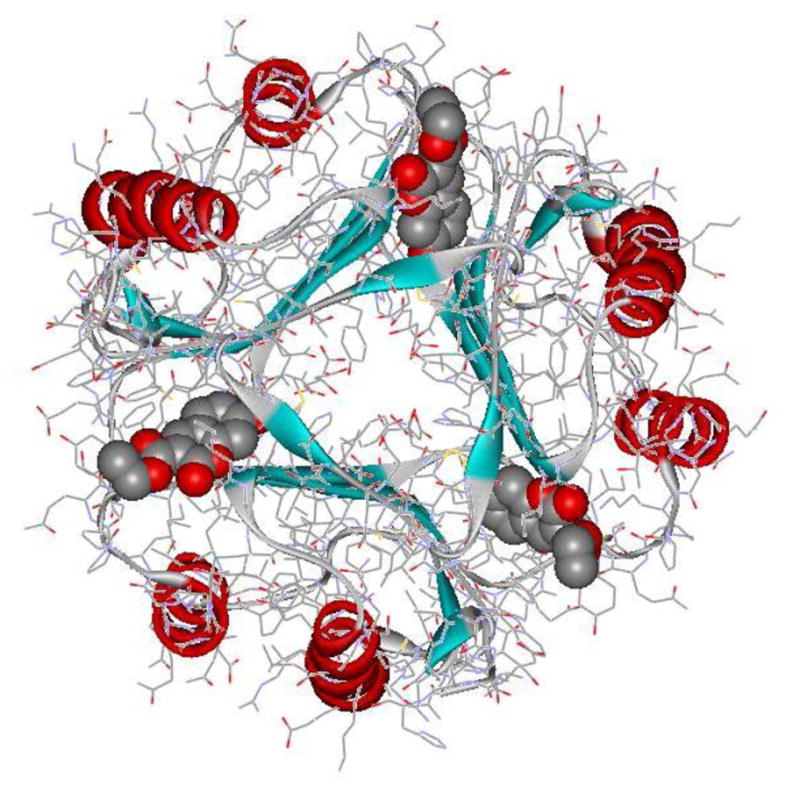

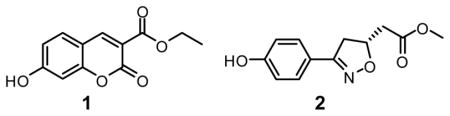

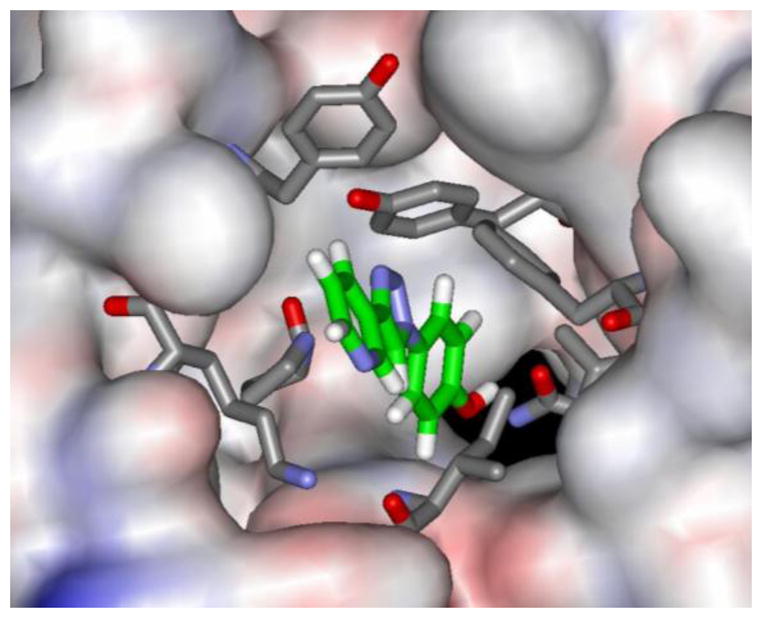

Besides being a cytokine, MIF shows enzymatic activity as a keto-enol tautomerase, which is likely vestigial in mammals.11 The 114-residue MIF monomer associates to form a symmetrical trimer with three tautomerase active sites (Figure 1).2,12,13 Though there is evidence that the MIF-CD74 contact occurs in the vicinity of the tautomerase active site,14 no crystal structure for a MIF-CD74 complex has been reported. Nevertheless, the availability of crystal structures for MIF has enabled structure-based discovery of small-molecule MIF tautomerase inhibitors.1,3 In conjunction with a protein-protein binding assay,4 it has also been possible to discover inhibitors of the more biologically significant MIF-CD74 complexation. Indeed, virtual screening by docking led to our identification of 11 structurally diverse inhibitors of MIF-CD74 binding with activities in the μM regime.15 Optimization of one series, featuring a N-benzyl-benzoxazol-2-one core, has provided compounds with IC50 values as low as 7.5 nM in the tautomerase assay and 80 nM in the MIF-CD74 binding assay.16

Figure 1.

1GCZ crystal structure (1.9 Å) for the MIF trimer with three copies of chromene derivative 1 (space-filling) in the active sites.

In parallel with the docking investigations, de novo design also was pursued using the program BOMB,17 which can build combinatorial libraries of analogs starting from a core placed in a binding site. Common features were apparent in available crystal structures for MIF complexed with the chromene analog 12,18 and the dihydroisoxazole 2 ((R)-ISO-1),13 which are both reported to be 7 μM tautomerase inhibitors. The crystal structures feature a hydrogen bond between the phenolic OH of the inhibitors and the side-chain CO of Asn97, which forms a backstop for the active site. There is also the potential for additional hydrogen-bonding with the NH of Ile64 and OH of Tyr95 as well as aryl-aryl interactions with Tyr36, Tyr95, and Phe113.

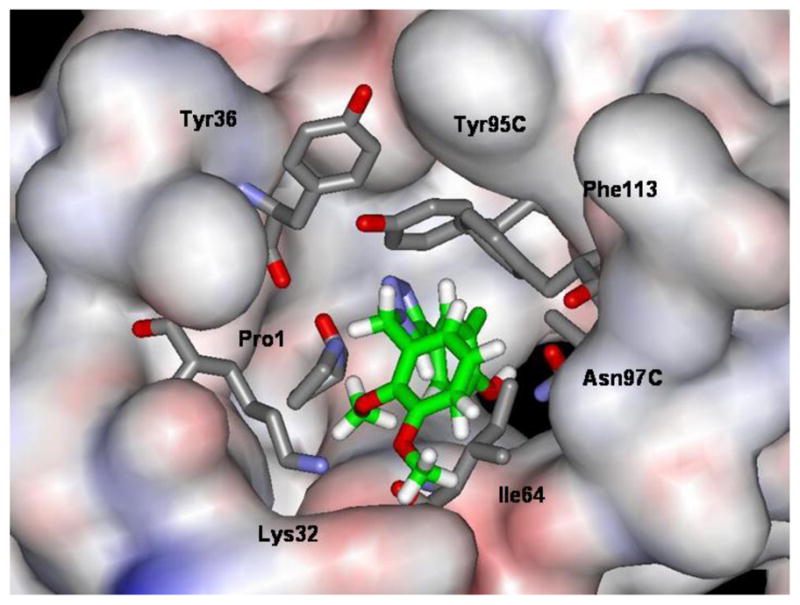

Thus, using phenol as the core hydrogen-bonded to Asn97, libraries were constructed in the motif HOPhHetR where Het is a 5- or 6-membered heterocycle and R is a small substituent. Roughly 100 choices for Het and 50 for R were initially considered using BOMB. Among well-scoring alternatives for Het, pyrazoles and triazoles were promising as were various aryl, CH2Ar, and OAr options for R. Since facile synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole derivatives was envisaged,19 they became the focus. For example, the dimethoxybenzyl derivative in Figure 2 could be constructed to yield a striking complex including hydrogen bonds with Asn97 and Tyr95, π-π interactions with Tyr95 and Phe113, and possible cation-π and/or cation-ether interactions with Lys32.

Figure 2.

Computed structure for 3g bound to MIF from BOMB after energy minimization using MCPRO and the OPLS/CM1A force field.

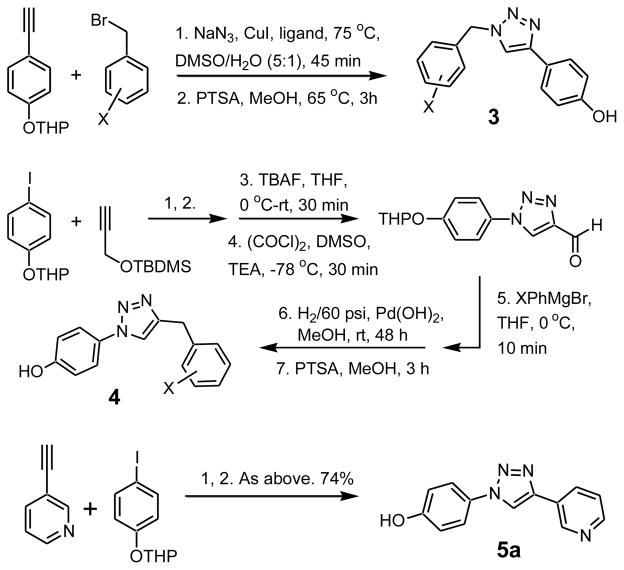

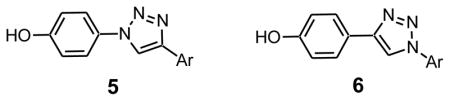

Substituted 1,2,3-triazoles were pursued in four series corresponding to structures 3, 4, 5, and 6. These represent two pairs of isomers, which are either 4-hydroxyphenyl substituted at the 1- or 4-position and with either a benzyl or heteroaryl group at the other site. The synthetic routes are summarized in Scheme 1. For the Cu(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions,19 a one-pot protocol utilizing terminal alkynes and in situ formation of aryl or benzyl azides from the corresponding bromides or iodides was highly effective.20 The typical procedure used 10 mol% CuI, 10 mol% sodium ascorbate, and 15 mol% trans-N,N′-dimethyl-1,2-cyclohexanediamine as ligand at 25–75 °C under argon. Compounds of types 3, 5, and 6 were readily accessible, while for 4 avoidance of benzyl acetylenes required a longer sequence featuring a Grignard reaction, catalytic hydrogenation of the resulting alcohol, and hydrolysis of the THP ether. Most reactions proceeded in 70–100% yield. The identity of all assayed compounds was confirmed by 1H (Bruker DRX-500) and 13C NMR and HRMS; purity was normally >95% as determined by reverse-phase HPLC.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of aryl-1,2,3-triazoles.

The MIF-CD74 binding assay was performed as previously presented.4,15 It features biotinylated MIF and immobilized CD74 ectodomain (CD7473–232) with streptavidin conjugated alkaline phosphatase processing p-nitrophenylphosphate as the reporter. Most compounds also were evaluated in a MIF tautomerase assay using 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (4-HPP) as the substrate.15,21 Compounds were tested at concentrations between 1 nM and 1 mM using human MIF, which was recombinantly prepared.22

The assay results are summarized in Table 1. In cases where some inhibition is observed, but it plateaus without reaching the 50% level, the maximum percent inhibition is reported. Such maxima were normally reached below 0.5 μM in the binding assay and in the μM range for the tautomerase assay. As discussed previously,15 a simple correlation between the results for the two assays is not expected. Docking calculations for all of the complexes were also carried out using Glide 5.5 in the extra precision (XP) mode.23 In previous studies, it was demonstrated that Glide XP scores correlated well with experimental log Ki or log IC50 values for complexes of 10 known MIF tautomerase inhibitors.15,16 The most favorable XP score, −9.4, for the known inhibitors is for a coumarin derivative with a reported Ki of 38 nM,2 and inhibitors with Ki values near 1 μM gave XP scores near −9.0. In comparing these results to the XP scores in Table 1, most of the triazole derivatives were not expected to be strong MIF tautomerase inhibitors. The exceptions turned about to be 3g and 3h, which yielded IC50 values of 0.75 and 2.5 μM. As illustrated in Figure 2, the binding of 3g to MIF may be enhanced by coordination of the ammonium group of Lys32 with the 2,3-dimethoxyl fragment of 3g.

Table 1.

Activities for 1,2,3-triazole derivatives from the MIF-CD74 and tautomerase (4-HPP) assays, and Glide XP scores.a

| Cmpd | X or Ar | IC50 or max % inhib | XP Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD74 | 4-HPP | |||

| 3a | - | NA | −7.2 | |

| 3b | 2-Me | NA | −7.0 | |

| 3c | 3-Me | NA | −7.2 | |

| 3d | 2-OMe | Agon | Agon | −6.9 |

| 3e | 3-OMe | 50 | −7.4 | |

| 3f | 4-OMe | NA | −7.2 | |

| 3g | 2,3-diOMe | 0.9 | 0.75 | −7.9 |

| 3h | 3-COOMe | 1.2 | 2.5 | −7.3 |

| 3i | 3-COOH | NA | −7.6 | |

| 4a | - | 3.5 | −6.7 | |

| 4b | 3-Me | 30% | 475 | −6.8 |

| 4c | 2-OH | 9% | 1000 | −7.0 |

| 4d | 3-OH | NA | NA | −6.8 |

| 4e | 4-OH | 23% | 690 | −6.7 |

| 4f | 2-OMe | 14% | 35% | −6.4 |

| 4g | 3-OMe | 8% | 40% | −6.5 |

| 4h | 4-OMe | 36% | 65 | −6.0 |

| 4i | 2,3-diOMe | NA | 530 | −7.1 |

| 4j | 3,4-diOMe | 22% | 70 | −6.6 |

| 5a | 3-pyridinyl | Agon | Agon | −6.5 |

| 5b | 1-naphthyl | NA | −5.9 | |

| 5c | 4-isoquinolinyl | Agon | Agon | −6.0 |

| 6a | 3-pyridinyl | 16% | 970 | −7.1 |

| 6b | 1-naphthyl | 23% | −6.4 | |

| 6c | 4-isoquinolinyl | 12% | 32 | −6.0 |

| 6d | CH2-2-pyridinyl | 30% | −7.3 | |

| 6e | CH2-3-pyridinyl | 20% | −7.3 | |

IC50 in μM. NA = inactive. Agon = agonist. XP scores from Glide v. 5.5 using the 1GCZ structure for MIF.

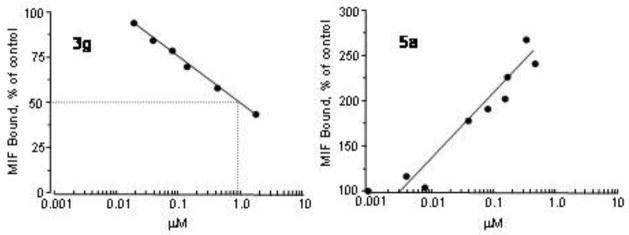

3g and 3h also emerged as the most potent antagonists in the MIF-CD74 binding assay with IC50 values near 1 μM. However, the most remarkable discovery was that 3d, 5a, and 5c increase the amount of MIF that remains bound to CD74 after washing. The increase in bound MIF depends linearly on the log of the agonist concentration. For 3d, there is a 40% increase in bound MIF at 500 nM, while there are 100% increases for 5a and 5c at ca. 100 nM and 150 nM, respectively. The contrasting behaviors for the antagonist 3g and agonist 5a are striking in Figure 3. The three compounds were also agonists in the tautomerase assay with the activity increasing by 31%, 23%, and 39% at 100 nM for 3d, 5a, and 5c, but not increasing significantly more at higher concentrations.

Figure 3.

Results of the MIF-CD74 binding assays for the antagonist 3g (left) and agonist 5a (right).

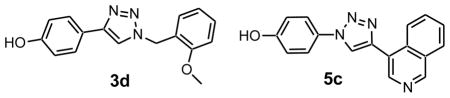

It would be fascinating to know the structural origins of the agonist behavior for the three compounds. Reasonable structures can be built for them bound in the tautomerase active site, as in Figure 4. For the tautomerase activity, it is possible that binding in one active site could enhance allosterically the activity in another site. It is also possible that the molecules bind to an alternative surface site that leads to the agonist character in both assays.18,24 Experimental structural studies are clearly desirable. It may be noted that small changes in a ligand have also been shown recently to interconvert agonist and antagonist character for the protein-protein association of Hsp40 and Hsp90.25

Figure 4.

Computed structure for 5a bound to MIF. Details as in Fig. 2. Negligible energetic preference is computed for the triazole ring being oriented up as shown or down (rotated 180°).

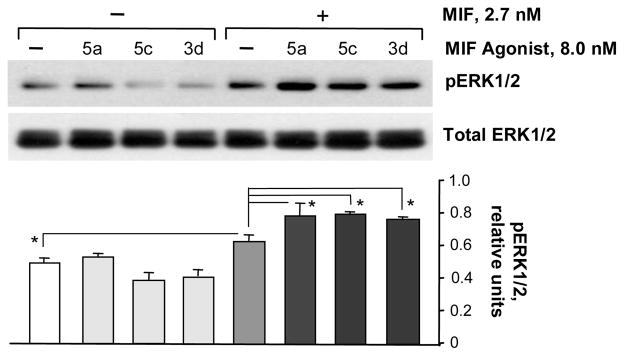

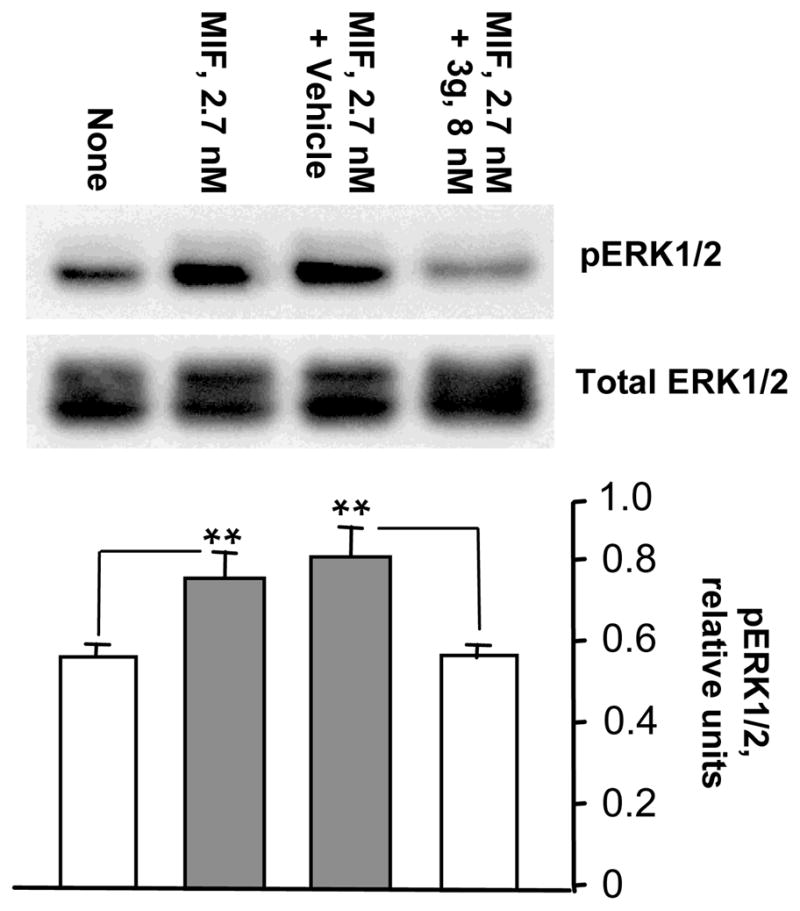

Finally, the potentially contrasting effects of the MIF agonists 3d, 5a, and 5c versus the MIF antagonist 3g on MIF signal transduction were explored in human target cells. The extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is of particular interest as aberrations in it are associated with hyperproliferative diseases as well as inflammatory disorders. Up-regulation of MIF increases ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a CD74-dependent manner.4 Specifically, human primary fibroblasts were incubated with MIF (2.7 nM trimer) together with vehicle control (DMSO) or with 3d, 5a, or 5c (each at 8 nM) for 30 min. The cells then were lysed and the intracellular contents of phospho-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 were detected by specific antibodies and western blotting (Figure 5). The addition of these compounds to MIF enhances ERK1/2 phosphorylation,4 while co-incubation of antagonist 3g under the same experimental conditions strongly inhibits the process (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Effects of the agonists on MIF-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation in human fibroblasts. The upper panel displays a representative western blot and the lower panel shows the numerical ratio of phosphorylated to total kinase protein determined by densitometric scanning for three separate experiments. *P<0.05.

Figure 6.

Effect of antagonist 3g on MIF-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation in human fibroblasts. The upper panel displays a representative western blot and the lower panel shows the numerical ratio of phosphorylated to total kinase protein determined by densitometric scanning for three separate experiments. **P<0.0025.

In summary, de novo design of small molecules to bind to the MIF tautomerase active site was carried out using the program BOMB and led to pursuit of aryl-1,2,3-triazole derivatives. Two ca. 1 μM tautomerase inhibitors, 3g and 3h, were discovered that also showed 1-μM potency in inhibiting the binding of MIF to its receptor CD74. Most significantly, three molecules, 3d, 5a, and 5c, were discovered that enhance the binding of MIF and CD74. The contrasting antagonist and agonist behaviors of 3g versus 3d, 5a, and 5c were then confirmed by monitoring the MIF-dependent phosphorylation of ERK kinases in human fibroblasts. The potential utility of the newly discovered agonists extends from fundamental studies of the biology of MIF to therapeutic applications as immune adjuvants or in limiting ischemic cardiac injury.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is expressed to the National Institutes of Health (AI042310, AR049610, AR050498, GM032136) and the Treat B. Johnson Fund at Yale for support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bucala R. Nature. 2000;408:146. doi: 10.1038/35041654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orita M, Yamamoto S, Katayama N, Fujita S. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1297. doi: 10.2174/1381612023394674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garai J, Lorand T. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:1091. doi: 10.2174/092986709787581842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leng L, Metz CN, Fang Y, Xu J, Donnelly S, Baugh J, Delohery T, Chen Y, Mitchell RA, Bucala R. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1467. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi X, Leng L, Wang T, Wang W, Du X, Li J, McDonald C, Chen Z, Murphy JW, Lolis E, Noble P, Knudson W, Bucala R. Immunity. 2006;25:595. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer-Siegler KL, Iczkowski KA, Leng L, Bucala R, Vera PL. J Immunol. 2006;177:8730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacher M, Metz CN, Calandra T, Mayer K, Chesney J, Lohoff M, Gemsa D, Donnelly T, Bucala R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller EJ, Li J, Leng L, McDonald C, Atsumi T, Bucala R, Young LH. Nature. 2008;451:578. doi: 10.1038/nature06504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell RR, III, Li J, Coven DL, Pypaert M, Zechner C, Palmeri M, Giordano FJ, Mu J, Birnbaum MJ, Young LH. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:495. doi: 10.1172/JCI19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma H, Wang J, Thomas DP, Tong C, Leng L, Wang W, Merk M, Zierow S, Bernhagen J, Ren J, Bucala R, Li J. Circulation. 2010;122:282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.953208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingerle-Rowson G, Kaleswarapu DR, Schlander C, Kabgani N, Brocks T, Reinart N, Busch R, Schütz A, Lue H, Du X, Liu A, Xiong H, Chen Y, Nemajerova A, Hallek M, Bernhagen J, Leng L, Bucala R. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1922. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01907-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubetsky JB, Swope M, Dealwis C, Blake P, Lolis E. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7346. doi: 10.1021/bi990306m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lubetsky JB, Dios A, Han J, Aljabari B, Ruzsicska B, Mitchell R, Lolis E, Al Abed Y. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senter PD, Al-Abed Y, Metz CN, Benigni F, Mitchell RA, Chesney J, Han J, Gartner CG, Nelson SD, Todaro GJ, Bucala R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011569399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cournia Z, Leng L, Gandavadi S, Du X, Bucala R, Jorgensen WL. J Med Chem. 2009;52:416. doi: 10.1021/jm801100v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hare AA, Leng L, Gandavadi S, Du X, Cournia Z, Bucala R, Jorgensen WL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:5811. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen WL. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:724–733. doi: 10.1021/ar800236t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLean LR, Zhang Y, Li H, Choi YM, Han Z, Vaz RJ, Li Y. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:1821. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2596. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen J, Bolvig S, Liang X. Synlett. 2005:2941. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamps SL, Taylor AB, Wang SC, Hackert ML, Whitman CP. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9671. doi: 10.1021/bi000373c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernhagen J, Mitchell RA, Calandra T, Voelter W, Cerami A, Bucala R. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14144. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6177. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho Y, Crichlow GV, Vermeire JJ, Leng L, Du X, Hodsdon ME, Bucala R, Cappello M, Gross M, Gaeta F, Johnson K, Lolis EJ. Proc Natl Acad USA. 2010;107:11313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002716107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wisén S, Bertelsen EB, Thompson AD, Patury S, Ung P, Chang L, Evans CG, Walter GM, Wipf P, Carlson HA, Brodsky JL, Zuiderweg ERP, Gestwicki JE. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:611. doi: 10.1021/cb1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]