Abstract

Infection of the stomach with Helicobacter pylori is an important risk factor for gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric carcinoma. Although it has been well established that persistent colonization by H. pylori is associated with adaptive Th1 responses, the innate immune responses leading to these Th1 responses are poorly defined. Recent studies have shown that the activation of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1) in gastric epithelial cells plays an important role in innate immune responses against H. pylori. The detection of H. pylori-derived ligands by cytosolic NOD1 induces several host defense factors, including antimicrobial peptides, cytokines, and chemokines. In this paper, we review the molecular mechanisms by which NOD1 contributes to mucosal host defense against H. pylori infection of the stomach.

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic, gram-negative bacterium that colonizes human gastric mucosa [1, 2]. Although most individuals with a chronic gastric infection of H. pylori are asymptomatic, this bacterium causes peptic ulcer or gastric cancer in a subpopulation of susceptible hosts [1, 2]. The development of gastric disease associated with H. pylori infection is determined by the interplay between bacterial virulence factors and host immune responses. The cag-pathogenicity island (PAI) is one of the most important virulence factors of H. pylori. Infection with strains of H. pylori carrying cag-PAI is associated with severe gastric disease, including gastric cancer [3].

Chronic infection with H. pylori is characterized by a strong T helper type 1 (Th1) response in the gastric mucosa [4, 5]. Th1 cells produce IFN-γ-mediated mucosal host defense against this organism as shown by the fact that IFN-γ-deficient mice fail to eradicate the bacteria from their stomachs upon oral administration of this organism [6]. Although it is well established that the gastric mucosa of patients with H. pylori infection is characterized by adaptive Th1 responses, the innate immune responses leading to such Th1 responses are poorly understood. Pattern recognition molecules particularly Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a crucial role in host defense against mucosal pathogens. TLRs are evolutionarily conserved receptors, which recognize microbial antigens and contribute to host defense by producing proinflammatory cytokines and antimicrobial peptides [7]. The activation of TLRs in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by TLR ligands associated with H. pylori has in fact been shown to be involved in the generation of protective Th1 responses against H. pylori [8]. In addition, the neutrophil-activating protein of H. pylori induces Th1 responses via TLR2-mediated IL-12 secretion in APCs [9]. Thus, it is clear that the detection of H. pylori-associated antigens by APCs expressing TLRs plays a role in the induction of protective anti-H. pylori Th1 responses.

Given the fact that most gastric APCs are localized in the submucosal areas and that H. pylori adheres to the luminal surface of the epithelium [10], it is likely that innate immune responses by gastric epithelial cells (ECs) directly activated by the organism are involved in the immunopathogenesis of H. pylori-associated gastric diseases. TLR signaling may be involved in the development of H. pylori-associated gastric disease since patients with gastric adenocarcinoma are more likely to carry the TLR4 polymorphisms [11]. However, on the other hand, TLR signaling may not necessarily play a major role since gastric ECs have been shown to be hypo-responsive to TLR ligands [12]. Another possibility is that epithelial cell signaling occurs through Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, Leucine-rich Repeat-containing (NLR) proteins, that is, a rapidly emerging family of innate immune regulatory molecules that function much like TLRs but with different signaling mechanisms [13]. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1) is of particular relevance in this context since NOD1, a member of the NLR family proteins, recognizes small peptides derived from peptidoglycan (PGN), a component of bacterial cell walls, and is expressed in APCs and gastric ECs [14]. In addition, Viala et al. has shown that eradication of H. pylori requires the sensing of PGN by cytosolic NOD1 expressed in gastric ECs [15]. Since this latter discovery, several mechanisms regarding NOD1-mediated mucosal host defense against H. pylori have been proposed. In this paper, we focus on these mechanisms with the aim of explaining just how NOD1 signaling contributes to gastric inflammation and host defense against H. pylori.

2. Expression of NOD1

NOD1 consists of a C-terminal LRR (Leucine-rich region), a central NOD, and an N-terminal CARD (caspase-activating domain) domain [14]. Whereas TLRs are associated with the plasma membrane or endosomal vesicles, NOD1 is expressed in the cytosol [14]. NOD1 is mainly expressed by cells—APCs and ECs—that are exposed to microorganisms [14]. Importantly, most gastrointestinal cell lines and primary ECs express NOD1 [15, 16].

NOD1 expression is regulated by proinflammatory cytokines. IFN-γ activates the promoter of NOD1 via nuclear translocation of IFN-regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) to up-regulate the expression of NOD1 in intestinal ECs whereas NF-κB activation by TNF does not alter the NOD1 expression in these cells [16, 17].

3. Signaling Pathways of NOD1

It is now established that NOD1 senses a small molecule derived from bacterial cell wall PGN. A minimum motif of NOD1 ligand is γ-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid—called iE-DAP. PGN derived from most gram-positive bacteria lacks iE-DAP. In contrast, PGN derived from most gram-negative bacteria contains iE-DAP. Thus, NOD1 functions as a sensor for gram-negative bacteria. In support of this idea, it has been shown that NOD1 participates in host defense against mucosal infection with gram-negative bacteria such as Shigella, Escherichia coli, and H. pylori [18, 19] although no functional mutations have been found to be associated with upper gastrointestinal diseases caused by chronic infection with H. pylori [20].

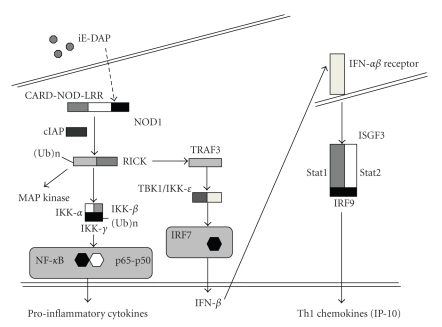

One pathway of NOD1 signaling relates to its ability to activate NF-κB and MAP kinases [14]. Such signaling is initiated by the detection of NOD1 ligands by the LRR domain of NOD1 which is then followed by the recruitment of a downstream effector molecule, RICK [14]. RICK is a CARD-containing serine/threonine kinase that physically binds to NOD1 through a CARD-CARD interaction [14]. RICK then undergoes K63-linked ubiquitination and acquires the ability to recruit and activate TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) [21]; the latter, in turn, initiates activation of NF-κB subunits through phosphorylation and K48-linked ubiquitination of IκBα. This sequence of events suggests that the binding of RICK to NOD1 and its K63-linked polyubiquitination is a key step in the NOD1-mediated signaling cascade with respect to responses involving NF-κB and MAP kinases and, as we shall see to other responses as well. This supposition is fully supported by the fact that NOD1 responses are severely curtailed in RICK-deficient cells [14].

The above NOD1 signaling pathway emphasizes the importance of ubiquitination in the signaling cascade. On the one hand, conjugation of K48-linked polyubiquitin chains with the inhibitory protein IκBα leads to proteasomal degradation of IκBα and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits such as p65 and p50. On the other hand, conjugation of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains to RICK, rather than causing RICK degradation leads to the creation of a scaffold that enables recruitment of signaling components, such as TAK1. The ligases that conjugate K63-linked polyubiquitin chains to RICK have recently been identified as the cellular inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (cIAP), cIAP1, and cIAP2 [22]. These proteins bind to NOD1 following the latters' activation by its ligands and have C-terminal RING finger domains with E3 ligase activity which then K63-ubiquitinate the RICK (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways of NOD1. NOD1 activation induces an interaction between RICK and TRAF3 that results in the production of IFN-β through activation of TBK1, IKKε, and IRF7. IFN-β production leads to production of IP-10 through transactivation of ISGF3 (Stat1-Stat2-IRF9 complex). NF-κB activation induced by NOD1 ligand leads to production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-8.

As shown in recent studies [19, 23, 24], the stimulation of ECs with NOD1 ligands leads to robust production of proinflammatory chemokines. We confirmed and extended these findings with studies showing that such stimulation induced Th1 chemokines (IFN-γ-induced protein of 10 kDa, IP-10) in gastrointestinal ECs including freshly isolated primary ECs [17] both in the presence and absence of IFN-γ. Initially, we and others attributed such induction to a signaling pathway involving NF-κB, along the lines described above. We noted, however, that the possible involvement of NF-κB was based largely on signaling studies utilizing transfected cells, in which NOD1 and/or an NF-κB reporter gene were overexpressed, rather than on studies employing cells expressing endogenous NOD1 stimulated under physiologic conditions. This introduced the possibility that signaling pathways not involving NF-κB activation play an important role in NOD1 induction of chemokines in EC. In an extensive series of studies to investigate this possibility we found that indeed, stimulation of EC by NOD1 ligand and production of IP-10 was not accompanied by substantial NF-κB activation, but rather by the induction of type I IFN which leads to IP-10 production by inducing the IP-10 transcription complex, IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) [17]. This comes about via a unique NOD1 signaling pathway that involves initial interaction of activated RICK with TRAF3, followed by the activation of TANK-binding kinase 1(TBK1) and IKKε and downstream IRF7 to induce the production of IFN-β and, as mentioned ISGF3 (Figure 1). ISGF3, which is a heterotrimer composed of Stat1, Stat2, and IRF9, not only acts as a transcription factor for IP-10, but also for IRF7 which induces further IFN-β production and further rounds of IP-10 production. Overall, these studies showed that, at least with respect to ECs, NOD1 utilizes a signaling pathway more commonly identified with cell signaling by viruses. Whether this signaling pathway also defines NOD1 function in other kinds of cells, such as macrophages, remains to be seen.

4. NOD1 Activation in Helicobacter pylori Infection

The majority of patients with H. pylori-associated gastritis have a higher NOD1 expression in gastric epithelial cells as compared with controls or H. pylori-nonassociated gastritis [20], which suggests the involvement of NOD1 signaling in the development of human gastric inflammation. In addition, animal studies demonstrate that a marked increase of bacterial load in the stomachs of NOD1-deficient mice is observed upon acute infection with cag-PAI-positive, but not cag-PAI-negative H. pylori as compared with NOD1-intact mice [15, 17]. These data are related to the fact that the detection of H. pylori-derived PGN by gastric ECs is at least partially dependent on a functional type IV secretion apparatus. Thus, as shown by Viala et al., H. pylori expressing functional cag-PAI efficiently delivered radio-labeled PGN into the ECs, whereas H. pylori strain 251—harboring nonfunctional cag-PAI—failed to deliver radio-labeled PGN [15]. In addition, these finding were supported by studies showing that infection with H. pylori induced IL-8 production by the gastric epithelial cell line, AGS cells, in an NOD1/cag-PAI-dependent manner [25]. It should be noted, however, that Kaparakis et al. have recently provided evidence for the existence of a cag-PAI-independent mechanism for NOD1 activation [26]. These authors purified outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) from cag-PAI-positive and -negative bacteria. H. pylori-derived OMVs containing numerous components of bacterial cell walls including PGN, induced IL-8 production by AGS cells via an NOD1-dependent and cag-PAI-independent fashion. OMVs activate the cytosolic NOD1 of ECs through lipid rafts. In addition, NOD1-deficient mice exhibit defective innate and adaptive immune responses to OMVs upon oral challenge with OMVs [26]. Patients infected with strains lacking a functional type IV secretion system still have inflammation and Th1 responses. These data regarding NOD1 activation by OMVs may partially explain the mechanisms by which NOD1-mediated Th1 responses against H. pylori are induced in the absence of functional cag-PAI. On the basis of this new data, further studies to determine the conditions under which NOD1 activation upon H. pylori infection requires functional type IV secretion apparatus are warranted.

5. Molecular Mechanisms of NOD1-Mediated Mucosal Host Defense against H. pylori Infection

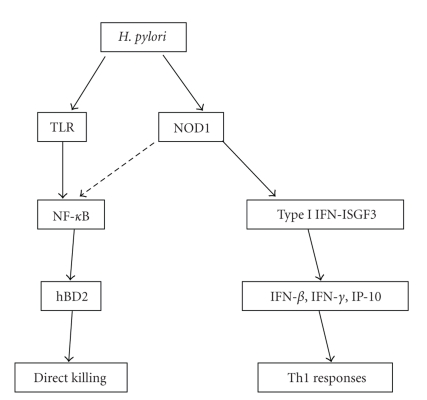

The generation of Th1 responses is required for mucosal host defense against H. pylori infection [4, 6]. Although the mechanism by which recognition of H. pylori-derived PGN by cytosolic NOD1 activates the protective response is not completely understood, two main models have been proposed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Molecular mechanisms of NOD1-mediated mucosal host defense against H. pylori. Infection of gastric epithelial cells with H. pylori activates type I IFN signaling, which leads to the generation of protective Th1 responses. H. pylori infection induces hBD2 production by epithelial cells mainly via TLR signaling pathways.

The first model for the role of NOD1 activation in H. pylori infection is based on the antimicrobial activity of defensins produced by ECs. Grubman et al. showed that H. pylori infection induces the production of human β defensin 2 (hBD2) by AGS cells in an NOD1/cag-PAI-dependent fashion [25]. Transfection of siRNA specific to hBD2 impairs the killing of H. pylori, as shown by the increased number of bacteria in culture supernatants from AGS cells infected with cag-PAI-positive H. pylori. These authors imply that NOD1 induction of hBD2 upon infection with cag-PAI-positive H. pylori may be mediated by NF-κB activation, but this is unclear since NF-κB activation is assessed by reporter gene assays that may not reflect endogenous NF-κB regulation [25]. Consistent with these results, the expression of murine β-defensin 4 (an orthologue of hBD2) is markedly reduced in the gastric mucosa of NOD1-deficient mice as compared with NOD1-intact mice [27]. These data regarding hBD2 induction by NOD1 suggest that NOD1 mediates host defense by the direct killing of H. pylori through induction of hBD2. However, the contribution of NOD1-induced defensins to the generation of Th1 responses remains unknown.

The second model for the role of NOD1 activation in H. pylori infection is based on the production of type I IFN and activation of the ISGF3 signaling mediated by NOD1. As we described in the previous section regarding NOD1 signaling pathways, the stimulation of gastrointestinal ECs including primary cells with NOD1 ligands leads to a robust production of IFN-β and the subsequent induction of ISGF3 [17]. We therefore addressed the role of this new signaling pathway in cag-PAI-positive H. pylori infection. In in vitro studies we found that H. pylori infection of AGS cells led to a massive increase of IFN-β and IP-10 production, which was accompanied by the activation of both Stat1 and Stat2, suggesting that cag+ H. pylori organisms do indeed activate epithelial cells via the IFN-β-ISGF3 pathway. Although H. pylori infection of the AGS cells results in NF-κB activation, NF-κB activation induced by H. pylori infection is independent of NOD1. The infection of AGS cells in the presence of siRNA specific for NOD1 resulted in the impaired nuclear translocation of Stat1 and production of IFN-β and IP-10, but unchanged nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunit, p65 [17]. These results are consistent with previous studies of Hirata et al. [28], who showed that H. pylori organisms can activate NF-κB in epithelial cell lines through MyD88-dependent mechanisms, but not NOD1-dependent mechanisms, and Viala et al. who reported that primary gastric epithelial cells infected with H. pylori produce chemokines in the absence of the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 [15].

In further in vivo studies of NOD1 activation during H. pylori infection we found a marked increase of bacterial load in the stomachs of NOD1-deficient mice as compared with NOD1-intact mice. Furthermore, this was associated with reduced production of type I IFN-ISGF3-associated cytokines and chemokines such as IFN-β, IP-10, and IFN-γ rather than NF-κB-associated cytokines such as TNF. Thus, the activation of type I IFN and ISGF3 signaling via NOD1 is responsible for the generation of protective Th1 responses against H. pylori [17]. This idea was confirmed by the fact that gene silencing of Stat1, a component of ISGF3, increases the bacterial burden in the stomach of NOD1-intact mice due to impaired Th1 and type I IFN responses. Therefore, it is likely that NOD1-mediated type I IFN production and ISGF3 activation provide protective Th1 responses upon infection with cag-PAI-positive H. pylori. In support of this model, IP-10 expression is observed in the gastric mucosa of patients with chronic H. pylori infection [5].

Recent studies addressing the role of NOD1 in mucosal host defense against H. pylori have been focusing on acute innate responses as assessed by cell-culture or animal infection models. Thus, it is unclear how NOD1 activation is involved in the development of various gastric diseases associated with chronic H. pylori infection. In this regard, IL-17 may play an important role in the chronic inflammatory responses to H. pylori infection as shown by the overproduction of this cytokine in H. pylori-infected human gastric mucosa [29]. In addition, vaccination of mice against H. pylori results in efficient eradication due to enhanced IL-17 production in the gastric mucosa [30, 31]. It is possible that NOD1 activation in response to H. pylori infection is involved in the generation of gastric Th17 responses since NOD1 triggering is required to instruct the onset of both Th1 and Th17 responses [32].

6. Conclusions

Infection with cag-PAI-positive H. pylori leads to the activation of NOD1 in gastric ECs and to the induction of several host defense factors including hBD2, IFN-β, and IP-10, all of which regulate bacterial growth. Recent studies have shown that NOD1 activation is mediated in ECs largely, if not entirely, by NOD1 induction of IFN-β and thus a signaling pathway ordinarily activated by viral infection. This has important implications for our views on how the mucosal system utilizes innate immune mechanisms to deal with chronic bacterial infections. Interestingly, proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by TLR ligands are markedly enhanced in the presence of NOD1 ligands. Therefore, it is possible that the synergistic activation of NOD1 and TLRs in gastric APCs also plays a role in mucosal host defense against this organism. Thus, future studies addressing whether or not NOD1 expression in APCs contributes to host defense against H. pylori will be of great interest.

Abbreviations

- APCs:

Antigen-presenting cells

- CARD:

Caspase-activating domain

- cIAPs:

cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins

- ECs:

Epithelial cells

- hBD2:

human β defensin 2

- IP-10:

IFN-γ-induced protein of 10 kDa

- IRF:

IFN-regulatory factor

- ISGF3:

IFN-stimulated gene factor 3

- LRR:

Leucine-rich repeats

- NLR:

Nod-like receptor

- NOD1:

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-1

- OMVs:

Outer membrane vesicles

- PAI:

Pathogenicity island

- PGN:

Peptidoglycan

- TAK1:

TGF-β-activated kinase 1

- Th1:

T helper type 1

- TLRs:

Toll-like receptors.

References

- 1.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(11):784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peek RM, Jr., Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(1):28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatakeyama M. Oncogenic mechanisms of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(9):688–694. doi: 10.1038/nrc1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh T, Wakatsuki Y, Yoshida M, et al. The vast majority of gastric T cells are polarized to produce T helper 1 type cytokines upon antigenic stimulation despite the absence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;34(5):560–570. doi: 10.1007/s005350050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eck M, Schmausser B, Scheller K, et al. CXC chemokines Groα/IL-8 and IP-10/MIG in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2000;122(2):192–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawai N, Kita M, Kodama T, et al. Role of gamma interferon in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammatory responses in a mouse model. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(1):279–285. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.279-285.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-Like receptor signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2004;4(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rad R, Brenner L, Krug A, et al. Toll-Like receptor-dependent activation of antigen-presenting cells affects adaptive immunity to Helicobacter pylori . Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):150–163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amedei A, Cappon A, Codolo G, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori promotes Th1 immune responses. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(4):1092–1101. doi: 10.1172/JCI27177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori . Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):1009–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukata M, Abreu MT. Role of Toll-Like receptors in gastrointestinal malignancies. Oncogene. 2008;27(2):234–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrero RL. Innate immune recognition of the extracellular mucosal pathogen, Helicobacter pylori . Molecular Immunology. 2005;42(8):879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ting JPY, Duncan JA, Lei Y. How the noninflammasome NLRs function in the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327(5963):286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1184004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A, Watanabe T. Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2006;6(1):9–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viala J, Chaput C, Boneca IG, et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nature Immunology. 2004;5(11):1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hisamatsu T, Suzuki M, Podolsky DK. Interferon-γ augments CARD4/NOD1 gene and protein expression through interferon regulatory factor-1 in intestinal epithelial cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(35):32962–32968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe T, Asano N, Fichtner-Feigl S, et al. NOD1 contributes to mouse host defense against Helicobacter pylori via induction of type I IFN and activation of the ISGF3 signaling pathway. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(5):1645–1662. doi: 10.1172/JCI39481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukazawa A, Alonso C, Kurachi K, et al. GEF-H1 mediated control of NOD1 dependent NF-κB activation by Shigella effectors. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000228. Article ID e1000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JG, Lee SJ, Kagnoff MF. Nod1 is an essential signal transducer in intestinal epithelial cells infected with bacteria that avoid recognition by Toll-Like receptors. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(3):1487–1495. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1487-1495.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstiel P, Hellmig S, Hampe J, et al. Influence of polymorphisms in the NOD1/CARD4 and NOD2/CARD15 genes on the clinical outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Cellular Microbiology. 2006;8(7):1188–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasegawa M, Fujimoto Y, Lucas PC, et al. A critical role of RICK/RIP2 polyubiquitination in Nod-induced NF-κB activation. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27(2):373–383. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertrand MJM, Doiron K, Labbé K, Korneluk RG, Barker PA, Saleh M. Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis cIAP1 and cIAP2 are required for innate immunity signaling by the pattern recognition receptors NOD1 and NOD2. Immunity. 2009;30(6):789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamaillard M, Hashimoto M, Horie Y, et al. An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nature Immunology. 2003;4(7):702–707. doi: 10.1038/ni945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masumoto J, Yang K, Varambally S, et al. Nod1 acts as an intracellular receptor to stimulate chemokine production and neutrophil recruitment in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203(1):203–213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grubman A, Kaparakis M, Viala J, et al. The innate immune molecule, NOD1, regulates direct killing of Helicobacter pylori by antimicrobial peptides. Cellular Microbiology. 2010;12:626–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaparakis M, Turnbull L, Carneiro L, et al. Bacterial membrane vesicles deliver peptidoglycan to NOD1 in epithelial cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2010;12(3):372–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boughan PK, Argent RH, Body-Malapel M, et al. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-1 and epidermal growth factor receptor: critical regulators of β-defensins during Helicobacter pylori infection. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(17):11637–11648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirata Y, Ohmae T, Shibata W, et al. MyD88 and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 are critical signal transducers in Helicobacter pylori-infected human epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(6):3796–3803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caruso R, Fina D, Paoluzi OA, et al. IL-23-mediated regulation of IL-17 production in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;38(2):470–478. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeLyria ES, Redline RW, Blanchard TG. Vaccination of mice against H pylori Induces a strong Th-17 response and Immunity that is neutrophil dependent. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):247–256. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velin D, Favre L, Bernasconi E, et al. Interleukin-17 is a critical mediator of vaccine-induced reduction of Helicobacter infection in the mouse model. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(7):2237–2246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritz JH, Le Bourhis L, Sellge G, et al. Nod1-mediated innate immune recognition of peptidoglycan contributes to the onset of adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2007;26(4):445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]