Abstract

BACKGROUND

In vitro culture (IVC) and IVF of preimplantation mouse embryos are associated with changes in gene expression. It is however not known whether ICSI has additional effects on the transcriptome of mouse blastocysts.

METHODS

We compared gene expression and development of mouse blastocysts produced by ICSI and cultured in Whitten's medium (ICSIWM) or KSOM medium with amino acids (ICSIKSOMaa) with control blastocysts flushed out of the uterus on post coital Day 3.5 (in vivo). In addition, we compared gene expression in embryos generated by IVF or ICSI using WM. Global pattern of gene expression was assessed using the Affymetrix 430 2.0 chip.

RESULTS

Blastocysts from ICSI fertilization have a reduction in the number of trophoblastic and inner cell mass cells compared with embryos generated in vivo. Approximately 1000 genes are differentially expressed between ICSI blastocyst and in vivo blastocysts; proliferation, apoptosis and morphogenetic pathways are the most common pathways altered after IVC. Unexpectedly, expression of only 41 genes was significantly different between embryo cultured in suboptimal conditions (WM) or optimal conditions (KSOMaa).

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that fertilization by ICSI may play a more important role in shaping the transcriptome of the developing mouse embryo than the culture media used.

Keywords: ICSI, embryos, microarray, gene expression, culture medium

Introduction

It is estimated that 1% of children in the western world are born with the help of assisted reproductive techniques (ART). Whereas these techniques are thought to be safe, several studies report an increased risk of unique complications associated with the use of IVF and ICSI (Anthony, 2002; Cox et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2002; Schieve et al., 2002; DeBaun et al., 2003). The widespread use of ICSI, currently accounting for over 60% of the fertilization procedures in USA (Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, 2008 www.sart.org) has sparked controversy because ICSI bypasses several physiologic events which would usually occur during fertilization. ICSI involves introduction of the sperm tail into the ooplasm and may be associated with suboptimal sperm nuclear decondensation (Markoulaki et al. 2007). In addition, ICSI-generated zygotes cleave at a slower rate, have a reduced hatching rate and a reduced cell number. ICSI zygotes also exhibit shorter calcium oscillations with an altered pattern (Kurokawa and Fissore, 2003). Importantly, Fernandez-Gonzalez et al. found that ICSI-generated mice using fresh spermatozoa develop long-term consequences, such as obesity and organomegaly, whereas ICSI-generated mice using frozen–thawed spermatozoa had a more severe phenotype, including aberrant growth, abnormal behavior, early aging and increased incidence of tumors (Fernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2008).

In our earlier studies, we showed that in vitro culture (IVC) of zygotes to the blastocyst stage alters their global gene expression patterns (Rinaudo and Schultz, 2004; Rinaudo et al., 2006). In addition, IVF is associated with additional changes in global gene expression and development (Giritharan et al., 2007). In order to investigate the effect that ICSI has on mouse preimplantation embryo development, and expand upon our prior IVC and IVF studies, we carried out experiments fertilizing embryos by ICSI and culturing embryos in different conditions, both optimal and suboptimal. Specifically, morphologic and gene expression studies were performed on blastocysts fertilized by ICSI and grown in vitro either in Whitten's medium (WM) (ICSIWM group) or in KSOM with amino acids (ICSIKSOMaa group) compared with those fertilized and grown in vivo (in vivo group). In addition, we compared the current data from ICSI embryos cultured in WM to our previous data from IVF embryos cultured in WM. Therefore, any comparisons between the IVFWM and ICSIWM groups would tease out the effects of gamete manipulation using IVF and ICSI.

Materials and Methods

Collection of mature oocytes, preimplantation mouse embryos and ICSI procedure

Oocytes and embryos were isolated from super-ovulated dams as previously described (Rinaudo and Schultz, 2004). Briefly, CF-1 female mice were injected with 5IU pregnant mare's serum gonadotrophin and 46–48 h later with 5IU hCG. The following morning, oocytes were obtained from the ampullae. Spermatozoa were collected from B6D2F1/J male mice (10–11 weeks old). After mice were sacrificed, the two caudal epididymides were removed, punctured gently with 30-G needles under a dissecting microscope and transferred with sterile forceps into 1 ml pre-warmed (37°C) EGTA Tris-HCl buffered solution containing 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.2, 50 mM EGTA and 50 mM NaCl in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and then incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The top 0.8 ml sperm suspension was carefully aspirated and used immediately for ICSI. Only oocytes with first polar body were microinjected using a Piezo drill (PMM Controller, Prime Tech, Ibaraki, Japan), as described (Li et al., 2009). Then fertilized oocytes were washed and cultured in either WM or KSOM with amino acids to the blastocyst stage under 5% CO2 in humidified air at 37°C. Late-cavitating blastocysts of similar morphology were harvested at ∼112 h post-hCG for ICSI groups and 96 h post-hCG for control in vivo group. Each treatment was repeated four times. Each time, sperm from one male and oocytes from two to three females were used for fertilization of ICSI groups. For in vivo groups, eggs were collected from two to three females after overnight breeding as one male per female. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Differential embryo staining

A modified dual nuclear staining method described by Thouas et al. (2001) was performed to differentially stain inner cell mass (ICM) and trophoblast cell nuclei of fully developed blastocysts. Briefly, the blastocysts were exposed to 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in minimum essential medium (MEM; Invitrogen Corporation, USA) for 3–5 seconds, washed 3–5 times in MEM + polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP; Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated in MEM + PVP containing 100 µg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 seconds. The embryos were then washed 3–5 times in MEM + PVP and fixed overnight in 100% ethanol containing 25 µg/ml of bizbenzamide (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C. The embryos were mounted on a clean glass slide using glycerol and kept in a dark chamber until observed under fluorescent light using a standard Leica microscope (Model DMRB, Leica Microsystems AG, Germany).

The embryos were observed by fluorescent microscopy, and the numbers of ICM cell (blue) and trophectoderm (TE: red) nuclei were counted and photographed. The staining procedure was repeated at least three times per treatment group with different sets of blastocysts (n ≥ 12).

RNA extraction and amplification

Total RNA was extracted from four independent biological replicates (10 blastocysts/replicate) using PicoPure RNA Isoloation Kit (Arcturus, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In column DNase treatment was performed using RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen Inc., USA) as described in the user guide of the PicoPure RNA isolation kit to remove the residual DNA. In each pool, five embryo equivalents of total RNA was used for reverse transcription (RT) followed by linear amplification of antisense cDNA strand, fragmentation and biotin labeling by using NuGEN Ovation Biotin System (NuGEN Technologies Inc., USA). Briefly, RNA is converted to cDNA with a unique DNA/RNA heteroduplex at one end. A linear isothermal DNA amplification process was conducted using DNA/RNA chimeric primer, DNA polymerase and RNase H in a homogeneous isothermal assay that provides highly efficient amplification of DNA sequences. The amplified cDNA strands were subjected to an enzymatic fragmentation and the fragmented product was then labeled with biotin. RNA and cDNA mass and size distribution were determined before and after amplification, and after fragmentation using the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA). Samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) >8 were selected for amplification. cDNA yield before fragmentation and labeling was 12–15 µg. Final yield of fragmented and biotinylated cDNA was 4–4.5 µg, of which 2.2 µg were used for microarray analysis.

Microarray preparation

Fragmented and biotin labeled cDNA samples were submitted to the Genomic Core Facility of the University of California San Francisco for GeneChip hybridization. The samples (four biological replicates per experimental group) were hybridized to mouse Affymetrix 430 2.0 GeneChips, then washed and stained on fluidics stations and scanned at 3 µm resolution according to the manufacturer's instructions (GeneChip Analysis Technical Manual, www.affymetrix.com).

cDNA preparation for real-time PCR analysis and RT–PCR

RT was accomplished by utilizing the commercially available first strand cDNA synthesis kit (iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit, Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA). The RT reactions were performed by following the kit manufacturer's protocol. For each treatment group the RT was repeated four times with RNA from different sets of blastocyst stage embryos.

The real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, Gene Expression Assays containing gene-specific primers and TaqMan probe (Applied Biosystems, USA), and 0.1 embryo equivalents of cDNA. The corresponding ABI TaqMan Assay-on-Demand probe/primer sets used were Mm00498012_m1 (Ube2a), Mm00438084_m1 (Ccng1), Mm99999915_g1 (Gapdh) and Mm00433832_m1 (Nr3c1). The real-time PCR was also performed using SyBr green PCR supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and primers for Bdnf, Nr3c1 and Gapdh genes with 0.1 embryo equivalents of cDNA from each treatment group. Primers which span at least two exons were designed using Primer3 software. Duplicates were used for each real-time PCR reaction; a minus template served as control. For each treatment group the real-time PCR was repeated four times. The real-time PCR data were analyzed within the log-linear phase of the amplification curve obtained for each probe/primer using the comparative threshold cycle method (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Data analysis

The cell number data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Cell numbers were compared using a mean separation procedure when analysis of variance showed significant F-values using Fisher's Least Significant Difference method. Results are reported as the mean values for each set of data ± SEM.

Microarray gene expression data analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the R software (http://www.r-project.org/) and the appropriate Bioconductor packages (http://www.bioconductor.org/) run under R. In order to remove all the possible sources of variation of a non-biological origin between arrays, densitometry values between arrays were normalized using the RMA (robust multi-array) normalization function implemented in the Bioconductor affylmGUI. Statistically significant differences between groups were identified using the rank product non-parametric test implemented in the Bioconductor RankProd package. Applying a Student's t-test with such a limited number of samples (four in each experimental group) is inappropriate as the obtained statistical significance is not robust; in this situation the mean and the standard deviation could be easily biased by outliers. We therefore carried out a non-parametric statistical test as a rough filter to narrow down the list of most relevant genes (Breitling and Herzyk, 2005). This non-parametric method is highly efficient, robust and widely used for microarray data analysis (Cervello et al., 2010). The Rank Product method has proven to be superior to other statistical methods for microarray data analysis in our and other authors' experience (Hong and Breitling, 2008). Moreover, the rank product approach includes a multiple hypothesis test for raw P-value correction to ascertain a false positive rate similar to false discovery rate correction. Data of the microarray are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Genes flagged as ‘present' or ‘marginal' in at least one hybridization, based on raw perfect match and mismatch as determined by ‘mas5calls' function on the Bioconductor affymetrix package, were considered expressed genes.

Functional annotations were carried out using the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis platform (http://www.ingenuity.com/).

Results

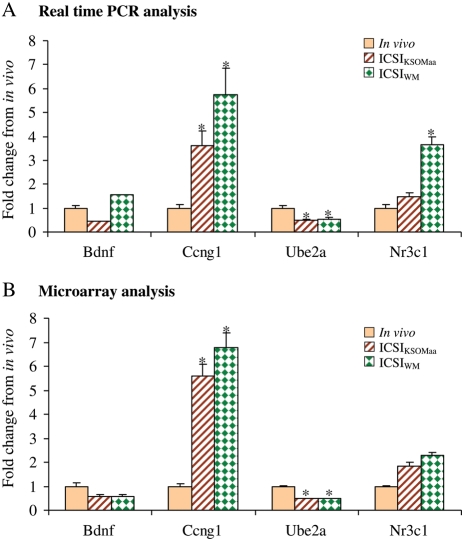

Validation of microarray data using real-time PCR

Published evidence confirms that microarray data are robust and reliable (Morey et al., 2006). In order to evaluate the reproducibility of the data, we performed multiple quality control analysis. Initially, we only utilized expanded blastocysts of similar morphology and we performed the experiments using four independent biological replicates. We confirmed that the quality of RNA was optimal, utilizing only RNA samples with RIN >8. We then performed in silico quality control analysis of the amplified material: we found that cRNA quality was excellent. Finally, we utilized real-time RT–PCR to confirm the microarray results obtained in this study (Fig. 1). In particular, we chose one gene with increased expression in the ICSI group (Ccgn1), one gene with decreased expression (Ube2a) and two genes with no change in expression between ICSI and in vivo blastocysts (Bdnf and Nr3c1). Results confirm similar trend between microarray and real-time data. The only difference is represented by the statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase after RT–PCR in Nr3c1 expression in ICSIWM blastocysts, although the increase of Nr3c1 following microarray analysis in both media or RT–PCR in ICSIKSOMaa is not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Real-time PCR verification of gene expression data. Expression profile of brain derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), cyclin G1 (Ccng1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2A (Ube2a) and the nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1 (Nr3c1) genes in murine blastocysts produced by in vivo fertilization and culture (in vivo), ICSI and IVC in KSOM with amino acids (ICSIKSOMaa) and ICSI and IVC in WM (ICSIWM) using real-time PCR technique (A) and microarray technique (B). Bars represent SD. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference compare with in vivo at P < 0.05. Of note the genes tested by RT–PCR reflect the changes detected by microarray. The only difference is represented by the statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase after RT–PCR in Nr3c1 expression in ICSIWM blastocysts, while the increase of Nr3c1 following microarray analysis in both media or after RT–PCR in ICSIKSOMaa is not statistically significant.

Effect of ICSI and the culture medium on blastocyst cell number

Expanded mouse blastocysts are easily recognizable and therefore offer an excellent end-point for morphologic assessment. In order to investigate the effect of the method of fertilization and IVC on cell division and cell allocation, we counted the number of ICM and TE cell nuclei in expanded blastocysts. Only expanded blastocysts at the same stage of development were used for analysis (Table I). In vivo embryos had on average two additional ICM cells compared with ICSIKSOMaa and three additional ICM cells compared with ICSIWM embryos (P < 0.05). The ICSIWM and IVFWM embryos had reduced number of TE cells (n = 36 and 33 cells, respectively) compared with the ICSIKSOMaa (n = 43 cells) and the in vivo control embryos (n = 49, P < 0.05). Of note, the development of embryos after ICSI, was excellent. More than 70% of the injected eggs survived and more than 90% of the surviving eggs reached the 2-cell stage in both culture media. The blastocyst development rates for 2-cell embryos cultured in ICSIKSOM and ICSIWM were 80.7 and 76.4%, respectively.

Table I.

The method of fertilization affects the distribution of cells in ICM and TE of embryos.

| Treatment | # ICM cells (mean ± SEM) | # TE cells (mean ± SEM) | # Total cells (mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICSIKSOMaa (n = 31) | 11.51 ± 0.46b | 43.32 ± 1.22b | 54.83 ± 1.76b |

| ICSIWM (n = 12) | 10.79 ± 0.79b | 36.92 ± 1.22c | 46.92 ± 2.87c |

| IVFWM (n = 63) | 12.84 ± 0.42ab | 33.51 ± 1.28c | 46.35 ± 1.45c |

| In vivo (n = 46) | 13.80 ± 0.50a | 49.67 ± 1.50a | 63.48 ± 1.70a |

Numbers are expressed as means ± SEM. Values with different superscripts in each column differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Effect of ICSI and in vitro embryo culture on blastocyst global gene expression

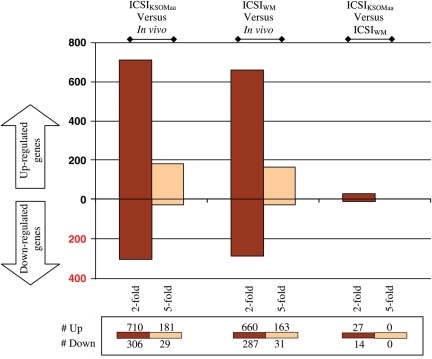

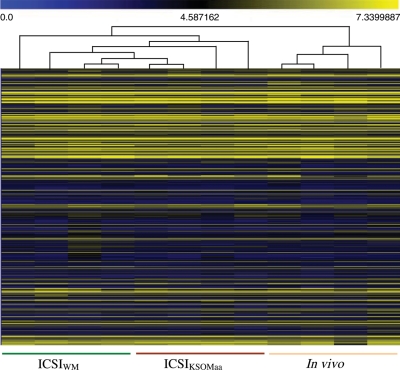

To analyze the global pattern of gene expression we used the mouse Affymetrix 430 2.0 microarray chip, which is believed to represent the complete mouse genome. Out of 12 035 total non-redundant genes with known gene symbols, 8847 (73.5%) were present in ICSIWM, 8408 (69.8%) in ICSIKSOMaa and 7758 (64.4%) in in vivo blastocysts. Pair-wise comparison revealed that a significant number of genes are differentially regulated following ICSIWM (947) or ICSIKSOMaa (1016) compared with in vivo control embryos (Fig. 2, P < 0.05). Most of the differentially regulated genes between the ICSI groups and in vivo are common (ICSIKSOMaa: 78.9%—802/1016; ICSIWM: 84.6%—802/947), with only 215 genes being uniquely different between ICSIKSOMaa and in vivo and 145 between ICSIWM and in vivo. This finding is important because it provides additional evidence of the robustness of the data. Indeed, unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis confirms these findings (Fig. 3). The samples segregated into two major clustering branches (ICSI and in vivo). However, all the replicate samples of the ICSI embryos cultured in WM and KSOMaa did not show a clear separation, indicating that the ICSI procedure itself affects the transcriptome of the blastocyst and that the culture media plays only a minor role.

Figure 2.

Summary of up-regulated and down-regulated genes for the following comparisons: ICSIKSOMaa versus in vivo, ICSIWM versus in vivo, ICSIKSOMaa versus ICSIWM. Each comparison in the graph shows the number of genes statistically different when comparing the four replicates of one group with the four replicates of the other group. The numbers below each comparison indicate how many genes are statistically up-regulated or down-regulated (P < 0.05) more than 2-fold or 5-fold.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering with heat-map of ICSIKSOMaa, ICSIWM and in vivo embryos based on their gene expression profile. Unsupervised clustering was performed to analyze similarities among replicate samples across all treatment groups tested. Colors correspond to relative RNA abundance for the transcripts detected; each is represented by a horizontal bar in the heat-map. Yellow indicates high expression and blue denotes low expression.

The entity of fold changes was higher than expected: 20.6% (210/1016) of the genes were changed more than 5-folds between ICSIKSOMaa and in vivo, and 20.4% (194/947) were different between ICSIWM and in vivo blastocysts.

Remarkably, a reduced number of genes were differentially expressed in ICSIKSOMaa embryos compared with ICSIWM (41 genes, P < 0.05); in addition only three genes were changed more than 3-fold between the two groups, indicating a minor effect of culture on gene expression following ICSI procedure.

The list of significantly different genes after each pair-wise comparison with the relative expression profiles is summarized in Supplementary data, Table S1.

Pathways analysis (Table II) reveals that similar classes are altered in embryos generated by ICSI and in vivo, independently of the culture media used. In particular there is an increase in alteration of pathways indicating mitochondrial dysfunction (ubiquinone biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorilation and mitochondrial dysfunction pathways) and alteration of metabolic pathways (N glycan degradation, branch chained amino acids and butanoate metabolism). Only the hepatocytes growth factor (HGF) signaling pathway and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway are uniquely different between ICSIKSOMaa and in vivo, while several classes are uniquely changed between ICSIWM and in vivo [Oct4-dependent pathway; production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in macrophages; CDK5 signaling; TR/RXR Activation].

Table II.

Overrepresented canonical pathways in comparisons among ICSIKSOM, ICSIWM and in vivo embryos (P < 0.05).

| Ingenuity canonical pathways | Ratio | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Altered pathways with fold change in ICSI embryos (both ICSIWM and ICSIKSOM) compared with in vivo embryos | ||

| Signaling | ||

| GABA receptor signaling | 0.109 | Abat (4.6, 3.6), Gabra5 ( −3.1, −3.3), Gabrb2 (−2.7, −2.5), Gabrg1 (−2.2, −2.3), Slc6a13 (6.5, 5.7) |

| Invasiveness signaling (Glioma) | 0.107 | F2r (3.6, 5.3), Itgb5 (4.2, 4.5), Rhod (5.3, 4.4), Rhoj (−2.7, −2.7), Rras (3.7, 3.9), Timp1 (4.8, 5.9) |

| Metabolism | ||

| Inositol metabolism | 0.143 | Adi1 (−2.5, −2.5), Aldh16a1 (3.3, 3.7), Blvrb (9.5, 11.1), Cyba (6.5, 8.5), Dhrs1 (5.4, 4.3), Dhrs13 (3.7, 3.7), Lamb2 (4.7, 4.5), Ndor1 (4.1, 4.1), Ndufa6 (3.6, 3.4), Recql4 (3.7, 3.5), Retsat (3.3, 3.5), Tm7sf2 (3.9, 3.6) |

| Butanoate metabolism | 0.133 | Abat (4.6, 3.6), Aldh2 (3.5, 3.5), Dcxr (14.3, 15.1), Ech1 (4.4, 5.7), Hadha (4.0, 4.1), Nlgn1 (−2.6, −2.8), Oxct1 (3.9, 4.1), Sdhb (3.8, 4.0) |

| N-glycan degradation | 0.133 | Man1b1 (4.1, 3.4), Man1c1 (3.1, 4.2), Man2c1 (3.8, 4.2), Manea (3.2, 3.5) |

| Urea cycle and metabolism of amino groups | 0.118 | Acy3 (6.1, 4.9), Ass1 (4.1, 3.7), Oat (3.4, 4.0), Pycrl (4.0, 3.4) |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 0.101 | Abat (4.6, 3.6), Aldh2 (3.5, 3.5), Bcat2 (4.7, 5.4), Bckdhb (4.4, 4.5), Ech1 (4.4, 5.7), Hadha (4.0, 4.1), Oxct1 (3.9, 4.1) |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.094 | Gpx3 (8.0, 7.7), Gpx7 (5.3, 6.2), Gstk1 (5.8, 4.7), Gstm2 (10.6, 13.4), Mgst3 (4.3, 3.9), Oplah (3.9, 4.0) |

| Mitochondrial function | ||

| Ubiquinone biosynthesis | 0.127 | Bckdhb (4.4, 4.5), Ndufa1 (4.0, 3.9), Ndufa13 (3.8, 3.6), Ndufa3 (4.1, 4.2), Ndufa6 (3.6, 3.4), Ndufb3 (3.8, 4.0), Ndufb7 (4.1, 4.0), Ndufs7 (4.4, 4.2), Ndufs8 (3.3, 3.3) |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.105 | Atp5e (3.4, 3.7), Atp5g2 (3.2, 3.9), Cox6b2 (22.9, 24.9), Cox7a1 (7.0, 5.8), Ndufa1 (4.0, 3.9), Ndufa13 (3.8, 3.6), Ndufa3 (4.1, 4.2), Ndufa6 (3.6, 3.4), Ndufb3 (3.8, 4.0), Ndufb7 (4.1, 4.0), Ndufs7 (4.4, 4.2), Ndufs8 (3.3, 3.3), Ppa2 (6.6, 7.7), Sdhb (3.8, 4.0), Uqcr (4.1, 4.2) |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 0.092 | Cox6b2 (22.9, 24.9), Cox7a1 (7.0, 5.8), Gpx7 (5.3, 6.2), Ndufa13 (3.8, 3.6), Ndufa3 (4.1, 4.2), Ndufa6 (3.6, 3.4), Ndufb3 (3.8, 4.0), Ndufb7 (4.1, 4.0), Ndufs7 (4.4, 4.2), Ndufs8 (3.3, 3.3), Sdhb (3.8, 4.0), Snca (−2.6, −2.6) |

| Pathways uniquely changed between ICSIWM and in vivo embryos | ||

| Signaling | ||

| Role of Oct4 in mammalian embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 0.044 | Fgf4 (−2.3), Rxrb (3.5) |

| CDK5 signaling | 0.034 | Egr1 (−2.6), Ppp1r11 (3.3), Ppp1r3a (−2.5) |

| TR/RXR activation | 0.033 | Ppargc1a (−2.2), Rxrb (3.5), Ucp2 (3.2) |

| Production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages | 0.031 | Map3k4 (3.7), Mapk13 (3.9), Ppp1r11 (3.3), Ppp1r3a (−2.5), Rnd2 (3.8) |

| Pathways uniquely changed between ICSIKSOM and in vivo embryos | ||

| Signaling | ||

| HGF signaling | 0.04 | Ccnd1 (−2.2), Elf3 (3.4), Elf5 (3.7), Map3k6 (3.5) |

| Metabolism | ||

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 0.042 | Aldh3b2 (3.4), Galm (3.2), Ldha (4.0), Pfkm (3.7) |

| Pathways uniquely changed between ICSIKSOM and ICSIWM embryos | ||

| Signaling | ||

| RhoA signaling pathways | 0.019 | Myl9 (2.05), Sept4 (2.04) |

| Metabolism | ||

| One-carbon pool by folate | 0.048 | Mthfd2 (2.33) |

| Pathways changed between IVFWM and ICSIWM | ||

| Signaling | ||

| Invasiveness signaling (Glioma) | 0.125 | F2r (−7.87), Itgb5 (−3.41), Rhod (−3.28), Rhoj (2.35), Rnd2 (−2.86), Rras (−4.83), Timp1 (−6.65) |

| Metabolism | ||

| Urea cycle and metabolism of amino groups | 0.176 | Acy3 (−3.30), Aldh18a1 (−5.21), Cps1 (3.72), Oat (−3.77), Pycrl (−3.31), Srm (−4.52) |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.125 | Ggt1 (−3.80), Gpx4 (−3.72), Gpx7 (−4.64), Gstk1 (−3.40), Gstm2 (−5.77), Mgst1 (2.19), Mgst3 (−3.05), Oplah (−5.19) |

| Phospholipid degradation | 0.103 | Dgka (−3.23), Hmox1 (−3.99), Lamb2 (−3.89), Napepld (−3.84), Pla1a (−3.25), Pla2g10 (−2.96), Plcd1 (−5.23), Pld3 (−3.05), Sphk2 (−3.39) |

| Selenoamino acid metabolism | 0.132 | Cbs (−5.85), Cth (−5.93), Edf1 (−3.16), Ggt1 (−3.80), Mars2 (−3.00) |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.092 | Agpat2 (−3.34), Dgka (−3.23), Hmox1 (−3.99), Lamb2 (−3.89), Napepld (−3.84), Pcyt2 (−4.84), Pemt (−2.59), Pla1a (−3.25), Pla2g10 (−2.96), Plcd1 (−5.23), Pld3 (−3.05), Sphk2 (−3.39) |

| Glutamate metabolism | 0.132 | Abat (−5.49), Cad (−4.01), Cps1 (3.72), Nadsyn1 (−2.47), Tgm4 (−3.55) |

| Inositol metabolism | 0.131 | Adi1 (2.20), Aldh16a1 (−3.80), Blvrb (−6.23), Cyba (−7.99), Dhrs1 (−4.05), Dhrs13 (−3.73), Hmox1 (−3.99), Lamb2 (−3.89), Ndor1 (−3.62), Recql4 (−4.66), Tm7sf2 (−4.01) |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 0.111 | Apobec1 (2.38), Cad (−4.01), Dhodh (−4.03), Mad2l2 (−3.24), Nme3 (−5.20), Nme4 (−3.70), Nt5m (−3.21), Pold1 (−4.68), Pold2 (−9.11), Pold4 (−3.58), Poli (−3.79), Polr2i (−5.06), Polr2l (−5.06), Polrmt (−3.35), Trub2 (−3.57), Uckl1 (−3.20), Upp1 (−3.39) |

| Mitochondrial function | ||

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 0.115 | Cox6b2 (−14.50), Cox7a1 (−5.05), Cox7b2 (−2.33), Dhodh (−4.03), Gpx4 (−3.72), Gpx7 (−4.64), Hsd17b10 (−3.24), Ndufa3 (−4.04), Ndufb3 (−3.61), Ndufb7 (−3.25), Ndufs2 (−3.71), Ndufs7 (−3.88), Ndufs8 (−3.32), Park7 (−3.28), Ucp2 (−3.22) |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.091 | Atp5e (−3.69), Cox6b2 (−14.50), Cox7a1 (−5.05), Cox7b2 (−2.33), Ndufa1 (−3.10), Ndufa3 (−4.04), Ndufb3 (−3.61), Ndufb7 (−3.25), Ndufs2 (−3.71), Ndufs7 (−3.88), Ndufs8 (−3.32), Ppa2 (−5.10), Uqcr (−4.16) |

| Ubiquinone biosynthesis | 0.127 | Bckdhb (−4.41), Edf1 (−3.16), Ndufa1 (−3.10), Ndufa3 (−4.04), Ndufb3 (−3.61), Ndufb7 (−3.25), Ndufs2 (−3.71), Ndufs7 (−3.88), Ndufs8 (−3.32) |

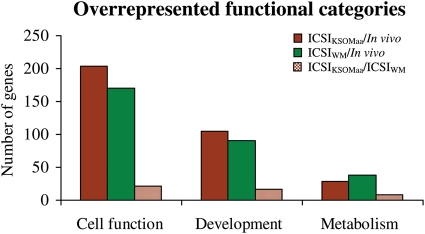

Functional categories analysis (Fig. 4 and Supplementary data, Table S2) shows that cell function, development and metabolic genes are affected by the method of fertilization and culture media used. Whereas all conditions used affect these functions, it is clear that the method of fertilization plays a more important role in altering the gene expression pattern than the media used to culture embryos.

Figure 4.

A total number of differentially expressed genes in cellular, developmental and metabolic functional catergories overrepresented in ICSIKSOMaa, ICSIWM, and in vivo embryos (P < 0.05). Detail information of cellular, developmental and metabolic functions with differentially regulated genes in each comparison is listed in Supplementary data, Table S2.

In fact, only 41 genes and two pathways (one-carbon pool by folate and RhoA signaling pathways) were different between ICSIKSOMaa and ICSIWM, while ∼1000 genes were different between ICSI embryos and in vivo embryos.

Effect of the method of fertilization (IVF or ICSI) on gene expression

Comparison of ICSIWM data with our previously generated gene expression data-IVFWM (Giritharan et al., 2007) showed differential expression of 981 genes. Eighteen percent (177/981) of these genes were changed more than 5-fold.

Overall multiple functional categories involved in cell function, development and metabolism (Supplementary data, Table S2) and pathways (Table II) are statistically different between IVFWMand ICSIWM.

Analysis of transporter genes (Table III) and imprinted and methylation genes (Table IV) reveals that several genes are affected by the method of fertilization.

Table III.

Differentially expressed transporter genes in ICSI and IVF embryos (P < 0.05).

| Gene symbol | Gene function | ICSIKSOM/In vivo | ICSIWM/In vivo | ICSIWM/ICSIKSOM | IVFWM/ICSIWM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slc10a3 | Sodium/bile acid cotransporter | −5.36 | −4.31 | NS | −4.00 |

| Slc12a4 | Potassium/chloride transporters | −4.98 | −4.07 | NS | −4.42 |

| Slc13a2 | Sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter | −5.19 | −4.51 | NS | −5.82 |

| Slc16a6 | Monocarboxylic acid transporter | −4.33 | −3.87 | NS | NS |

| Slc22a9 | Organic anion transporter | 4.40 | 4.55 | NS | NS |

| Slc25a28 | Mitochondrial iron transporter | −5.30 | −5.25 | NS | −4.98 |

| Slc27a3 | Fatty acid transporter | −3.32 | −3.28 | NS | −3.78 |

| Slc35c1 | GDP-fucose transporter | −3.79 | −3.63 | NS | −4.02 |

| Slc35d2 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine/UDP-glucose/GDP-mannose transporter | 2.64 | 2.60 | NS | 2.19 |

| Slc39a11 | Metal ion transporter | −3.24 | NS | NS | NS |

| Slc39a4 | Zinc transporter | −3.34 | −3.57 | NS | NS |

| Slc3a2 | Activators of dibasic and neutral amino acid transport | −3.27 | −4.25 | NS | NS |

| Slc44a4 | Choline transporter | −3.54 | −3.40 | NS | NS |

| Slc46a1 | Folate/heme transporter | −5.46 | −5.44 | NS | −7.58 |

| Slc5a12 | Sodium/glucose cotransporter | 2.64 | 2.82 | NS | NS |

| Slc5a6 | Sodium-dependent vitamin transporter | −3.08 | −3.79 | NS | −3.95 |

| Slc6a13 | Neurotransmitter (GABA) transporter | −5.66 | −6.49 | NS | −3.90 |

| Slc7a12 | Cationic amino acid transporter | 16.66 | 15.09 | NS | 10.24 |

| Slc7a13 | Cationic amino acid transporter | 2.38 | 2.40 | NS | 2.37 |

| Slco6b1 | Organic anion transporter | 2.87 | 2.73 | NS | 2.61 |

| Slco6c1 | Organic anion transporter | 3.35 | 3.34 | NS | 3.11 |

| Slc44a3 | Choline transporter | NS | NS | −2.10 | NS |

| Slc27a2 | Fatty acid transporter | NS | NS | −2.42 | NS |

| Slc27a4 | Fatty acid transporter | NS | NS | NS | −2.57 |

| Slc30a2 | Zinc transporter | NS | NS | NS | −3.74 |

| Slc37a4 | Glucose-6-phosphate transporter | NS | NS | NS | −4.56 |

| Slc38a7 | Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter | NS | NS | NS | −3.88 |

| Slc39a12 | Zinc transporter | NS | NS | NS | 2.00 |

| Slc4a2 | Anion exchanger | NS | NS | NS | −2.48 |

| Slc5a6 | Sodium-dependent vitamin transporter | NS | NS | NS | −3.95 |

| Slc7a3 | Cationic amino acid transporter | NS | NS | 2.07 | −7.65 |

| Slc9a1 | Sodium/hydrogen exchanger | NS | NS | NS | −4.18 |

| Slco6d1 | Organic anion transporter family | NS | NS | NS | 2.40 |

NS, not significant.

Table IV.

Imprinted and epigenetic genes differentially expressed in ICSI and IVF embryos compared with in vivo embryos with their fold changes (P < 0.05).

| Gene symbol | Gene function | In vivo/ICSIWM | In vivo/ICSIKSOMaa | ICSIWM/ICSIKSOMaa | IVFWM/ICSIWM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imprinted genes | |||||

| Asb4 | Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box-containing 4 | 2.17 | 2.86 | NS | NS |

| Cd81 | CD81 antigen | −13.92 | −13.91 | NS | NS |

| H19 | H19 fetal liver mRNA | 2.08 | NS | 3.68 | NS |

| Igf2as | Insulin-like growth factor 2, antisense | −3.32 | −4.40 | NS | −5.41 |

| Kcnq1 | Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily Q, member 1 | NS | NS | NS | 2.07 |

| Osbpl5 | Oxysterol binding protein-like 5 | NS | −3.65 | NS | −4.15 |

| Peg10 | Paternally expressed 10 | −18.85 | −21.75 | NS | −12.27 |

| Epigenetic regulating genes | |||||

| Hdac6 | Histone deacetylase 6 | −4.37 | −4.24 | NS | NS |

| Smarca1 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 1 | 2.82 | 2.50 | NS | NS |

| Wbp7 | WW domain binding protein 7 | −4.86 | −4.56 | NS | −4.59 |

| Mbd2 | Methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2 | NS | −3.53 | NS | NS |

| Smarca4 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 4 | NS | NS | NS | −3.36 |

NS, not significant.

Discussion

This study, for the first time, offers a complete overview of the changes in the global pattern of gene expression in ICSI or in vivo generated mouse embryos. This provides an overview of the transcriptional consequences of fertilizing eggs by different techniques and complements our previous work on the effect of different media and oxygen concentration on the transcriptome of mouse blastocysts (Rinaudo and Schultz, 2004; Rinaudo et al., 2006; Giritharan et al., 2007). The most notable finding is that the ICSI procedure plays a more important role in determining the blastocyst gene expression pattern than the culture media used (WM or KSOMaa).

Overall, there is a net reduction of ICM and TE cells in the ICSI group compared with the in vivo control. The reduction of cells is larger in TE cells (∼26% less cells in ICSIWM and 14% in ICSIKSOMaa) than ICM (∼10% less in ICSI embryos) of ICSI embryos. Since TE cells will give rise to the placenta, this suggests that the method of fertilization could affect more placenta formation than the embryo itself. The cell number data confirm findings of other investigators, who found that, in various species, ICSI-generated zygotes cleave at a slower rate and have reduced hatching rate and reduced cell number (Dumoulin et al., 2000; Bedford et al., 2003; Malcuit et al., 2006).

Although it is not possible to compare the present mouse findings with human data, it is interesting to note that lower hCG levels were found in human IVF gestations than in in vivo conception, implying reduced placental mass (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 1994). Assuming that an embryo with lower cell numbers will grow less, these findings could explain the fact that ART children have lower birthweight at term (McDonald et al., 2009).

The gene expression results confirm the morphologic studies. The ICSI embryos have a very distinct transcriptome compared with embryos fertilized in vivo, as shown by the unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis (Fig. 3). ICSI embryos have an increased dysregulation (both up- and down-regulation) in the expression of genes related to cellular function, development and metabolism. The down-regulation of several genes involved in cellular development and differentiation (Fig. 4 and Supplementary data, Table S2) implies that an alteration of developmental strategy could follow the preimplantation stress and explains the reduced number of cells in ICSI embryos. Overall, the increased number of dysregulated genes indicates that these embryos have an increased metabolism; this would suggest decreased fitness according to the ‘quiet embryo' hypothesis (Leese et al., 2008).

Pathway analysis offers additional insights (Table II): mitochondrial dysfunction and a disproportionately higher number of metabolic pathways occurring in mitochondria (inositol, butanoate, urea cycle and branched amino acid metabolism) are altered following ICSI. Individual gene analysis confirms these findings. For example, Cox6b2 (cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIb polypeptide 2) gene is increased more than 20-fold in ICSI embryos. This gene produces an isoform of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which catalyzes the electron transfer from reduced cytochrome c to molecular oxygen (Huttemann et al., 2003). Up-regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation genes indicates the increased metabolic need of the embryo.

Of note, mitochondrial dysfunction can result in reduced post-implantation development (Thouas et al., 2006) and can have long-lasting effects. For example, it has been hypothesized as the mechanism inducing the insulin-resistant phenotype observed in offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes (Petersen et al., 2004).

Among the signaling pathways modified after ICSI, the γ amino butyric (GABA) receptor signaling and invasiveness signaling are prominent. Autocrine and paracrine GABA signaling via GABAA receptors slow preimplantation embryonic growth by decreasing proliferation because of increased cellular arrest in the S phase (Andang et al., 2008). Alteration of invasiveness signaling could indicate suboptimal placentation. For example, Timp1, an inhibitor of cellular invasion (Paiva et al., 2009) and Itgb5 (integrin beta 5), an integrin involved in implantation (Massuto et al.) are up-regulated in ICSI placentas.

Alteration of multiple additional genes involved in placentation is present. This finding provides a molecular justification of the significant reduction in TE cells found in ICSI embryos. Prl2c2 (prolactin family 2, subfamily c, member 2) is expressed in large trophoblastic giant cells during the invasion (Adamson et al., 2002) and it is down-regulated 25-fold in ICSI embryos. Psg28 (pregnancy-specific glycoprotein 28) is expressed in giant cells and spongiotrophoblast of the placenta (Kromer et al., 1996), is implicated in immunomodulatory function to prevent rejection of embryo/fetus (Wynne et al., 2006) and is down-regulated more than 11-fold in ICSI blastocysts. Bex1 (brain-expressed X-linked 1) located close to Xist on the X chromosome, is down-regulated more than 16 times in ICSI embryos; while it does not appear to be epigenetically regulated, it is highly expressed in trophectodermal cells (Williams et al., 2002). Down-regulation of these genes could be associated with reduced placental development.

Alteration of multiple cellular transporters could indicate the placenta function is compromised. Among the transporter genes (Table III), Slc7a12 (solute carrier family 7, member 12) stands out for being down-regulated more than 18-fold in ICSI embryos; this gene is involved in the cationic amino acid transport (Closs et al., 2006). Dysregulation of other transporter genes has been associated with different metabolic or storage diseases. Although so far none of the following diseases have been linked to ART, alterations of these genes implies metabolic stress. Slc35c1 (solute carrier family 35, member C1) encodes a GDP-fucose transporter located in the Golgi apparatus. Mutations in this gene result in congenital disorder of glycosylation type IIc (Lubke et al., 2001). Slc39a4 (solute carrier family 39, member 4) encodes for a transmembrane protein required for zinc uptake in the intestine. Mutations in this gene result in acrodermatitis enteropathica, a rare inherited defect in the absorption of dietary zinc (Wang et al., 2002). Slc46a1 (solute carrier family 46 member 1) is a transmembrane proton-coupled folate transporter that facilitates the movement of folate and heme across membranes. Mutations in this gene cause a recessive form of folate malabsorption (Qiu et al., 2006).

Because abnormal DNA methylation can follow culture in vitro, we paid particular attention to imprinting and methylation genes (Doherty et al., 2000; Rolaki et al., 2007). Several imprinted genes are different between ICSI embryos and in vivo embryos (Table IV). Among them Cd81 and Peg10 are changed more than 10-fold. Cd81 encodes a tetraspanin that functions as an organizer of multi-molecular membrane complexes and as a result, regulates cell migration, fusion and signaling (Hemler, 2005). Cd81 is located close to the cluster of imprinted genes on murine chromosome 7 which is syntenic with the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome associated cluster of imprinted gene on human chromosome 11p15.5 region (Paulsen et al., 1998). Lim et al. (2009) reported that children born after ICSI with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome have an altered methylation in this region of chromosome 11. It is, however, important to remember that this gene is imprinted in mice but not humans and therefore conclusions valid in one model system may not be valid in another species. Peg10 (Paternally expressed 10) is an imprinted gene down-regulated more than 18-fold in ICSI embryos; it plays an important role in placental development and its deletion is associated with early embryonic lethality (Rawn and Cross, 2008).

Interestingly, additional genes that are not imprinted but are located on the X chromosome and therefore potentially subjected to selective epigenetic controls were altered. Among these, Ott (ovary testis transcribed) is a mouse X-linked multigene family gene specially expressed during meiosis in testis and ovary (Kerr et al., 1996), while Slc10a3 (solute carrier family 10 member 3) belongs to the sodium/bile acid cotransporter family and was originally cloned from placental tissue; it maps to a GC-rich region of the X chromosome and was identified by its proximity to a CpG island (Geyer et al., 2006).

Several genes involved in epigenetic regulation appear to be misregulated. Importantly Wbp7, Smarca1 and Hdac6 are altered in ICSI embryos.

Hdac6 belongs to the histone deacetylases (HDACs) family of enzymes that catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from lysine residues in histones and non-histone proteins, resulting in transcriptional repression. HDACs play a role in cell growth arrest, differentiation and death, and Hdac6 over expression has been associated with premature chromatin compaction in mouse oocytes and embryos (Verdel et al., 2003).

Smarca1 (SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 1) encoded protein has helicase and ATPase activity and regulates transcription by altering chromatin structure (Magnani and Cabot, 2009).

Wbp7 (WW domain binding protein 7) is a histone methyltransferase that methylates Lysine 4 of histone H3 resulting in an epigenetic mark favoring transcriptional activation. Mice lacking Wbp7 fail to develop beyond E9.5 (Lubitz et al., 2007).

The transcriptome comparison of ICSI embryos cultured in KSOMaa or WM and the comparison of ICSIWM and IVFWM blastocysts provided some of the most unanticipated findings of the study: the method of fertilization plays a more important role than the culture media to determine the transcriptome of the blastocysts.

Regarding the comparison of ICSIKSOMaa and ICSIWM, it appears that while ICSIWM embryos have a statistically reduced number of TE cells (18% less), only 41 genes (4%—versus ∼1000 genes different between in vivo and ICSI blastocysts) were differentially expressed; in addition the fold change differences were small and overall <4-fold. Interestingly, H19 is the only imprinted gene differentially expressed being up-regulated more than 3-fold in WM. This is not surprising, since culture in WM, as opposite to culture in KSOM, is associated with biallelic expression of the gene (Doherty et al., 2000).

Only three transporter genes are differentially regulated (Slc44a3; Slc27a2; Slc7a3).

Finally only two pathways were statistically different between ICSIKSOMaa and ICSIWM (RhoA signaling and one carbon folate pathways). Members of the Rho family of small guanosine triphosphatases have emerged as key regulators of the actin cytoskeleton, and furthermore, through their interaction with multiple target proteins, they ensure coordinated control of other cellular activities such as gene transcription and adhesion. Down-regulation of Mthfd2 (methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase—NADP+-dependent—2) is, however, notable as this gene is involved in folate metabolism and therefore could result in abnormal methyl donor availability for methyltransferases.

Complementary to the findings of ICSI embryos cultured in different media, the different gene expression pattern between IVFWM and ICSIWM confirms that the method of fertilization plays a fundamental role in determining the transcriptome of the preimplantation embryos. In fact, as many genes are different between IVFWM and ICSIWM (984 gene) as between ICSIKSOMaa and in vivo (1016) or ICSIWM and in vivo (947).

Pathways analysis confirms that similar pathways (Mitochondrial function pathways and metabolic pathways) are changed between IVFWM blastocysts and ICSIWM embryos as between ICSI embryos (both WM and KSOMaa) and in vivo embryos.

Interestingly, among the transporters differentially expressed, a subset is uniquely mis-expressed between IVFWM and ICSIWM blastocysts (Table III). Slc27a4 is involved in translocation of long-chain fatty acids across the plasma membrane and is required for fat absorption in early embryogenesis (Gimeno et al., 2003). Slc37a4 (solute carrier family 37 member 4) regulates glucose-6-phosphate transport from the cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum and is involved in ATP-mediated calcium sequestration in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mutations in this gene have been associated with various forms of glycogen storage disease (Schaub and Heyne, 1983).

Three epigenetic genes (Wbp7, Kcnq1 and Smarca4) were differentially regulated in IVFWM and ICSIWM embryos. Kcnq1 was down-regulated in ICSI embryos while Wbp7 and Smarca4 were up-regulated in ICSI embryos compared with IVF embryos. Smarca4 protein plays a fundamental roles controlling gene expression during early mammalian embryogenesis (Magnani and Cabot, 2009). Wbp7 also plays a key role in embryo development, and regulates the apoptosis and differentiation of cells into all three germ layers (Lubitz et al., 2007). Most recent evidence revealed an association of the Kcnq1 gene with the susceptibility to type 2 diabetes. Kcnq1 participates in the regulation of cell volume, which is, in turn, critically important for the regulation of metabolism by insulin. Kcnq1 counteracts the stimulation of cellular K+ uptake by insulin and thereby influences K+-dependent insulin signaling on glucose metabolism (Boini et al., 2009).

Importantly, this study does not address unequivocally whether the differences in gene expression described in ICSI-produced blastocysts are secondary to the ICSI procedure alone or the combination of ICSI and IVC. An ideal experiment would include the transcriptome analysis of blastocysts that were generated by ICSI, with the resulting two pronuclei embryos immediately transferred to recipients to eliminate the effects of in vivo culture. Whereas this experiment is feasible, it is technically difficult and requires multiple manipulations. The next best experiment is to observe the gene expression changes of zygote generated in vivo and cultured to the blastocyst stage (IVC embryos). We (Rinaudo and Schultz, 2004; Giritharan et al., 2007) and others (Wang et al., 2005; Zeng and Schultz, 2005; Fernandez-Gonzalez et al. 2009) have shown that culture conditions play an important role in shaping gene expression in developing embryos and blastocysts. In particular, in one study we showed that culture media and oxygen concentration play an independent role in affecting gene expression, with the oxygen concentration determining a synergistic increase in gene misregulation. IVC of zygotes in atmospheric oxygen (20% O2) was associated with markedly increasing misregulated genes (20% O2:WM: 354 genes changed more than 2-fold compared with in vivo flushed blastocysts; KSOMaa: 102 differentially expressed gene), compared to IVC of zygotes in physiologic oxygen concentration (5% O2: WM: 45 genes and KSOM 18 genes changed more than 2-fold, respectively; Rinaudo et al., 2006). In a separate study, we showed that a high number of transcripts was statistically different in blastocysts generated by IVF and cultured in WM 20% O2 when compared with in vivo control blastocysts, but the magnitude of the changes in gene expression was low and only a minority of transcripts (357) was changed more than 2-fold. Surprisingly, IVF embryos were different from IVC blastocysts cultured in WM 20% O2 (3058 transcripts were statistically different but only 98 transcripts were changed more than 2-fold; Giritharan et al., 2007). Fernandez-Gonzalez et al. (2009) compared the gene expressions of IVC embryos cultured in KSOM versus KSOM + fetal calf serum (FCS), and observed that the presence of FCS during IVC affected several genes involved in regulating epigenetic mechanisms. Their results are particularly relevant because the same authors found that adult animals resulting from IVC embryos cultured in KSOM + FCS displayed alteration of post-natal development and behavior (Fernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2004).

The above-mentioned studies and the present findings support the conclusion that each manipulation and culture conditions have an independent effect on the transcriptome of the developing embryo. Interestingly, the ICSI manipulation results in a higher number of genes being changed compared with all the other manipulations analyzed.

It is possible that the different pattern of calcium oscillation following ICSI (Kurokawa and Fissore, 2003) triggers a different wave of gene activation and therefore the effect of different culture media is less prominent. Consistent with this possibility is the finding that the S100a6 (S100 calcium binding protein A6), a calcium binding protein, is down-regulated more than 25-folds in the ICSI groups. S100a6 induces conformational changes and post-translational modifications of multiple cytoplasmic proteins (Santamaria-Kisiel et al., 2006). In particular, it interacts with p53 and modulates apoptosis (Grigorian et al., 2001).

Implication for future health

The most important clinical question relates to the long-term significance of the observed gene changes. These changes could be self-limited and isolated, like T-wave changes found on a healthy person EKG following intense physical exercise. In fact, while one rodent study found differences in selected gene expression in blastocysts generated by ICSI with mature spermatozoa or round spermatid injection (ROSI; Hayashi et al., 2003), other studies did not find any obvious long-term health consequences in ROSI mice (Tamashiro et al. 1999; Meng et al., 2002). On the other hand, it is possible that some of the differentially regulated genes might alter the development of additional genes, and as a result, potentially affect cellular and tissue development, as asserted by the developmental origin of health and disease hypothesis (Barker, 1998). Indeed, a cohort of ART pubertal children has been found to have slightly worse metabolic parameters than spontaneously conceived children of infertile couples (Ceelen et al., 2008). We believe that our database provides fundamental resources for understanding how the method of fertilization and culture conditions affect mouse preimplantation embryo development. Therefore the provided gene list could be useful to uncover the cellular mechanisms that can lead to long-term health consequences.

Overall, it appears that ICSI, IVF and in vivo produced mouse blastocysts have a very different transcriptome.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/.

Authors' roles

G.G.: Conception and design, collection and assembly of data and manuscript writing. M.W.L.: Collection of data. F.S.: Collection of data. F.J.E.: Data analysis and interpretation. J.A.H., A.D., E.M.: Data analysis and interpretation. K.C.K.L.: Collection of data. P.R.: Conception and design, manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by NICHD/NIH through cooperative agreement 1U54HD055764 as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research.

Supplementary Material

References

- Adamson SL, Lu Y, Whiteley KJ, Holmyard D, Hemberger M, Pfarrer C, Cross JC. Interactions between trophoblast cells and the maternal and fetal circulation in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2002;250:358–73. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)90773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andang M, Hjerling-Leffler J, Moliner A, Lundgren TK, Castelo-Branco G, Nanou E, Pozas E, Bryja V, Halliez S, Nishimaru H, et al. Histone H2AX-dependent GABA(A) receptor regulation of stem cell proliferation. Nature. 2008;451:460–464. doi: 10.1038/nature06488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony SBS, Dorrepaal C, Lindner K, Braat D, Ouden A. Congenital malformations in 4224 children conceived after IVF. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2089–2095. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.8.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. Mothers, Babies and Health in Later Life. 2nd edn. Glasgow: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford SJ, Kurokawa M, Hinrichs K, Fissore RA. Intracellular calcium oscillations and activation in horse oocytes injected with stallion sperm extracts or spermatozoa. Reproduction. 2003;126:489–499. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1260489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boini KM, Graf D, Hennige AM, Koka S, Kempe DS, Wang K, Ackermann TF, Foller M, Vallon V, Pfeifer K, et al. Enhanced insulin sensitivity of gene-targeted mice lacking functional KCNQ1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1695–R1701. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90839.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling R, Herzyk P. Rank-based methods as a non-parametric alternative of the T-statistic for the analysis of biological microarray data. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2005;3:1171–1189. doi: 10.1142/s0219720005001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceelen M, van Weissenbruch MM, Vermeiden JP, van Leeuwen FE, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Cardiometabolic differences in children born after in vitro fertilization: follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1682–1688. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervello I, Gil-Sanchis C, Mas A, Delgado-Rosas F, Martinez-Conejero JA, Galan A, Martinez-Romero A, Martinez S, Navarro I, Ferro J, et al. Human endometrial side population cells exhibit genotypic, phenotypic and functional features of somatic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closs EI, Boissel JP, Habermeier A, Rotmann A. Structure and function of cationic amino acid transporters (CATs). J Membr Biol. 2006;213:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s00232-006-0875-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GF, Burger J, Lip V, Mau UA, Sperling K, Wu BL, Horsthemke B. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection may increase the risk of imprinting defects. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:162–164. doi: 10.1086/341096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBaun MR, Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Association of in vitro fertilization with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and epigenetic alterations of LIT1 and H19. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:156–160. doi: 10.1086/346031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty AS, Mann MR, Tremblay KD, Bartolomei MS, Schultz RM. Differential effects of culture on imprinted H19 expression in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1526–1535. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumoulin JC, Coonen E, Bras M, van Wissen LC, Ignoul-Vanvuchelen R, Bergers-Jansen JM, Derhaag JG, Geraedts JP, Evers JL. Comparison of in-vitro development of embryos originating from either conventional in-vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:402–409. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Moreira P, Bilbao A, Jimenez A, Perez-Crespo M, Ramirez MA, Rodriguez De Fonseca F, Pintado B, Gutierrez-Adan A. Long-term effect of in vitro culture of mouse embryos with serum on mRNA expression of imprinting genes, development, and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5880–5885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308560101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Moreira PN, Perez-Crespo M, Sanchez-Martin M, Ramirez MA, Pericuesta E, Bilbao A, Bermejo-Alvarez P, de Dios Hourcade J, de Fonseca FR, et al. Long-term effects of mouse intracytoplasmic sperm injection with DNA-fragmented sperm on health and behavior of adult offspring. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:761–772. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.065623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez R, de Dios Hourcade J, Lopez-Vidriero I, Benguria A, De Fonseca FR, Gutierrez-Adan A. Analysis of gene transcription alterations at the blastocyst stage related to the long-term consequences of in vitro culture in mice. Reproduction. 2009;137:271–283. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer J, Wilke T, Petzinger E. The solute carrier family SLC10: more than a family of bile acid transporters regarding function and phylogenetic relationships. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;372:413–431. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno RE, Hirsch DJ, Punreddy S, Sun Y, Ortegon AM, Wu H, Daniels T, Stricker-Krongrad A, Lodish HF, Stahl A. Targeted deletion of fatty acid transport protein-4 results in early embryonic lethality. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49512–49516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giritharan G, Talbi S, Donjacour A, Di Sebastiano F, Dobson AT, Rinaudo PF. Effect of in vitro fertilization on gene expression and development of mouse preimplantation embryos. Reproduction. 2007;134:63–72. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian M, Andresen S, Tulchinsky E, Kriajevska M, Carlberg C, Kruse C, Cohn M, Ambartsumian N, Christensen A, Selivanova G, et al. Tumor suppressor p53 protein is a new target for the metastasis-associated Mts1/S100A4 protein: functional consequences of their interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22699–22708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Kurinczuk JJ, Bower C, Webb S. The risk of major birth defects after intracytoplasmic sperm injection and in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:725–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Yang J, Christenson L, Yanagimachi R, Hecht NB. Mouse preimplantation embryos developed from oocytes injected with round spermatids or spermatozoa have similar but distinct patterns of early messenger RNA expression. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1170–1176. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler ME. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev. 2005;6:801–811. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong F, Breitling RA. comparison of meta-analysis methods for detecting differentially expressed genes in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:374–382. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttemann M, Jaradat S, Grossman LI. Cytochrome c oxidase of mammals contains a testes-specific isoform of subunit VIb—the counterpart to testes-specific cytochrome c? Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;66:8–16. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr SM, Taggart MH, Lee M, Cooke HJ. Ott, a mouse X-linked multigene family expressed specifically during meiosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1139–1148. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.8.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromer B, Finkenzeller D, Wessels J, Dveksler G, Thompson J, Zimmermann W. Coordinate expression of splice variants of the murine pregnancy-specific glycoprotein (PSG) gene family during placental development. Eur J Biochem/FEBS. 1996;242:280–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0280r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M, Fissore RA. ICSI-generated mouse zygotes exhibit altered calcium oscillations, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-1 down-regulation, and embryo development. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:523–533. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leese HJ, Baumann CG, Brison DR, McEvoy TG, Sturmey RG. Metabolism of the viable mammalian embryo: quietness revisited. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:667–672. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MW, Willis BJ, Griffey SM, Spearow JL, Lloyd KC. Assessment of three generations of mice derived by ICSI using freeze-dried sperm. Zygote. 2009;17:239–251. doi: 10.1017/S0967199409005292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D, Bowdin SC, Tee L, Kirby GA, Blair E, Fryer A, Lam W, Oley C, Cole T, Brueton LA, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic features of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome associated with assisted reproductive technologies. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:741–747. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz S, Glaser S, Schaft J, Stewart AF, Anastassiadis K. Increased apoptosis and skewed differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells lacking the histone methyltransferase Mll2. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2356–2366. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubke T, Marquardt T, Etzioni A, Hartmann E, von Figura K, Korner C. Complementation cloning identifies CDG-IIc, a new type of congenital disorders of glycosylation, as a GDP-fucose transporter deficiency. Nat Genet. 2001;28:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani L, Cabot RA. Manipulation of SMARCA2 and SMARCA4 transcript levels in porcine embryos differentially alters development and expression of SMARCA1, SOX2, NANOG, and EIF1. Reproduction. 2009;137:23–33. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcuit C, Maserati M, Takahashi Y, Page R, Fissore RA. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the bovine induces abnormal [Ca2+]i responses and oocyte activation. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2006;18:39–51. doi: 10.1071/rd05131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoulaki S, Kurokawa M, Yoon SY, Matson S, Ducibella T, Fissore R. Comparison of Ca2 + and CaMKII responses in IVF and ICSI in the mouse. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:265–272. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massuto DA, Kneese EC, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Hooper RN, Ing NH, Jaeger LA. Transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) signaling is activated during porcine implantation: proposed role for latency-associated peptide interactions with integrins at the conceptus-maternal interface. Reproduction. 2010;139:465–478. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Murphy KE, Beyene J, Ohlsson A. Preterm birth and low birth weight among in vitro fertilization singletons: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Akutsu H, Schoene K, Reifsteck C, Fox EP, Olson S, Sariola H, Yanagimachi R, Baetscher M. Transgene insertion induced dominant male sterility and rescue of male fertility using round spermatid injection. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:726–734. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey JS, Ryan JC, Van Dolah FM. Microarray validation: factors influencing correlation between oligonucleotide microarrays and real-time PCR. Biol Proced Online. 2006;8:175–193. doi: 10.1251/bpo126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva P, Salamonsen LA, Manuelpillai U, Dimitriadis E. Interleukin 11 inhibits human trophoblast invasion indicating a likely role in the decidual restraint of trophoblast invasion during placentation. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:302–310. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.071415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen M, Davies KR, Bowden LM, Villar AJ, Franck O, Fuermann M, Dean WL, Moore TF, Rodrigues N, Davies KE, et al. Syntenic organization of the mouse distal chromosome 7 imprinting cluster and the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome region in chromosome 11p15.5. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1149–1159. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:664–671. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A, Jansen M, Sakaris A, Min SH, Chattopadhyay S, Tsai E, Sandoval C, Zhao R, Akabas MH, Goldman ID. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell. 2006;127:917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawn SM, Cross JC. The evolution, regulation, and function of placenta-specific genes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:159–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaudo P, Schultz RM. Effects of embryo culture on global pattern of gene expression in preimplantation mouse embryos. Reproduction. 2004;128:301–311. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaudo PF, Giritharan G, Talbi S, Dobson AT, Schultz RM. Effects of oxygen tension on gene expression in preimplantation mouse embryos. Fertil Steril. 2006;86((Suppl 4)):1252–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.017. 1265. e1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolaki A, Coukos G, Loutradis D, DeLisser HM, Coutifaris C, Makrigiannakis A. Luteogenic hormones act through a vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent mechanism to up-regulate alpha 5 beta 1 and alpha v beta 3 integrins, promoting the migration and survival of human luteinized granulosa cells. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1561–1572. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria-Kisiel L, Rintala-Dempsey AC, Shaw GS. Calcium-dependent and -independent interactions of the S100 protein family. Biochem J. 2006;396:201–214. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub J, Heyne K. Glycogen storage disease type Ib. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140:283–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00442664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Meikle SF, Ferre C, Peterson HB, Jeng G, Wilcox LS. Low and very low birth weight in infants conceived with use of assisted reproductive technology. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:731–737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2007. Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports, Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Tamashiro KL, Kimura Y, Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC, Yanagimachi R. Bypassing spermiogenesis for several generations does not have detrimental consequences on the fertility and neurobehavior of offspring: a study using the mouse. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1999;16:315–324. doi: 10.1023/A:1020406016312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thouas GA, Korfiatis NA, French AJ, Jones GM, Trounson AO. Simplified technique for differential staining of inner cell mass and trophectoderm cells of mouse and bovine blastocysts. Reprod Biomed Online. 2001;3:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thouas GA, Trounson AO, Jones GM. Developmental effects of sublethal mitochondrial injury in mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:969–977. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.048611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdel A, Seigneurin-Berny D, Faure AK, Eddahbi M, Khochbin S, Nonchev S. HDAC6-induced premature chromatin compaction in mouse oocytes and fertilised eggs. Zygote. 2003;11:323–328. doi: 10.1017/s0967199403002387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Zhou B, Kuo YM, Zemansky J, Gitschier JA. novel member of a zinc transporter family is defective in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:66–73. doi: 10.1086/341125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Cowan CA, Chipperfield H, Powers RD. Gene expression in the preimplantation embryo: in-vitro developmental changes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:607–616. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JW, Hawes SM, Patel B, Latham KE. Trophectoderm-specific expression of the X-linked Bex1/Rex3 gene in preimplantation stage mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61:281–287. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne F, Ball M, McLellan AS, Dockery P, Zimmermann W, Moore T. Mouse pregnancy-specific glycoproteins: tissue-specific expression and evidence of association with maternal vasculature. Reproduction. 2006;131:721–732. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Altieri E, Fabres C, Fernandez E, Mackenna A, Orihuela P. Predictive value of human chorionic gonadotrophin in the outcome of early pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and spontaneous conception. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:1550–1555. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F, Schultz RM. RNA transcript profiling during zygotic gene activation in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2005;283:40–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.