Abstract

Reduced bone mineral density (osteopenia) is a poorly characterized manifestation of pediatric and adult patients afflicted with Marfan syndrome (MFS), a multisystem disorder caused by structural or quantitative defects in fibrillin-1 that perturb tissue integrity and TGFβ bioavailability. Here we report that mice with progressively severe MFS (Fbn1mgR/mgR mice) develop osteopenia associated with normal osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. In vivo and ex vivo experiments, respectively, revealed that adult Fbn1mgR/mgR mice respond more strongly to locally induced osteolysis and that Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblasts stimulate pre-osteoclast differentiation more than wild-type cells. Greater osteoclastogenic potential of mutant osteoblasts was largely attributed to Rankl up-regulation secondary to improper TGFβ activation and signaling. Losartan treatment, which lowers TGFβ signaling and restores aortic wall integrity in mice with mild MFS, did not mitigate bone loss in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice even though it ameliorated vascular disease. Conversely, alendronate treatment, which restricts osteoclast activity, improved bone quality but not aneurysm progression in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice. Taken together, our findings shed new light on the pathogenesis of osteopenia in MFS, in addition to arguing for a multifaceted treatment strategy in this congenital disorder of the connective tissue.

INTRODUCTION

Mutations that affect the structure or expression of the extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoprotein fibrillin-1 cause pleiotropic manifestations in Marfan syndrome (MFS; OMIM-154700) by impairing connective tissue integrity and by promoting improper latent TGFβ activation (1). Consistent with the involvement of promiscuous TGFβ signaling in MFS pathogenesis, systemic administration of TGFβ-neutralizing antibodies to mouse models of MFS improves cardiovascular, skeletal muscle and lung abnormalities (2–5). Similarly, treatment with losartan, an angiotensin II receptor 1 (AT1R) blocker (ARB) that lowers TGFβ signaling (6,7), restores aortic wall architecture in mice with mild MFS (Fbn1C1039G/+ mice) and mitigates aortic root dilation in children with severe MFS (4,8). Although these findings are encouraging, there are reasons to believe that some MFS patients may not respond to losartan and/or that this treatment may not curtail other morbid manifestations of MFS, such as those affecting the skeleton (9–11).

Osteopenia is a controversial finding in MFS, especially in pediatric patients (12–19). Factors that contribute to ambiguity include the lack of standardized protocols to compare bone mineral density (BMD) between affected and healthy individuals, and the absence of robust normative data for children (11,20). While preliminary analyses suggest that mutations in fibrillin-1 cause osteopenia in mice, the underlying mechanism is similarly controversial due to inherent limitations of the mutant mouse lines employed in these studies (21–23). Progressive bone loss and reduced BMD in Tight skin (Tsk/+) mice were correlated with a decreased rate of osteoblast maturation in vitro and implicitly, with reduced bone formation in vivo (21). The Tsk mutation is a large internal duplication of fibrillin-1 that in heterozygosity interferes with microfibril biogenesis and leads to a phenotype that combines pulmonary and skeletal manifestations of MFS with cutaneous fibrosis of Stiff Skin syndrome (SSS; OMIM-184900) (24–27). The unusual nature of the Tsk mutation, together with the unique phenotype of Tsk/+ mice, however raises questions as to whether these animals truly replicate MFS pathogenesis. In contrast to Tsk/+ osteoblasts, recent analyses showed that cultured osteoblasts from Fbn1−/− mice mature slightly faster than wild-type cells and stimulate osteoclast activity in vitro more than control cells, suggesting a probable defect of bone resorption rather than bone formation in these mutant mice (22,23). Neonatal lethality of Fbn1−/− mice (28) has unfortunately precluded validating this conclusion through the analysis of bone remodeling in adult mice.

The present study therefore interrogated the role of fibrillin-1 in bone remodeling using a combination of in vivo and ex vivo experiments and a mouse model of progressively severe adult lethal MFS [Fbn1mgR/mgR mice (29)]. The results of our analyses indicate that osteopenia in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice is largely driven by increased bone resorption due to TGFβ-dependent dysregulation of the local coupling between osteoblast and osteoclast activities. Consistent with this observation, bisphosphonate restriction of osteoclast activity mitigated progressive bone loss in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice. In contrast, losartan treatment was only effective in improving vascular disease in this adult lethal model of MFS. Collectively, these findings suggest that a multifaceted treatment strategy will probably be required to target distinct cellular events that are responsible for organ-specific manifestations in MFS.

RESULTS

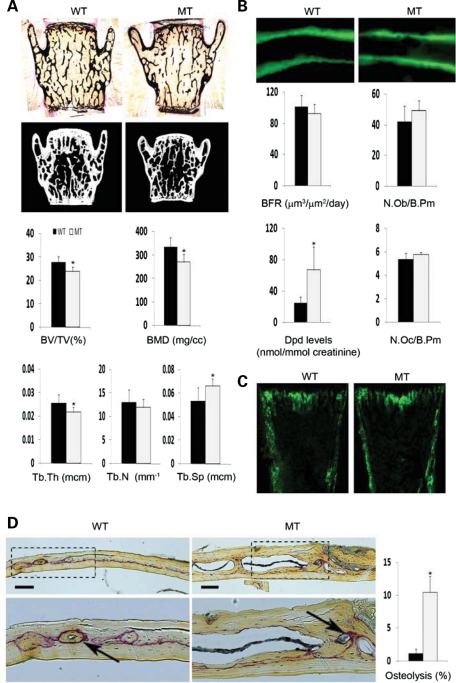

Fbn1mgR/mgR mice display normal bone formation and increased bone resorption

Fbn1mgR/mgR mice produce ∼15% of the normal amount of fibrillin-1 and have a reduced average lifespan of 2–4 months due to dissecting aortic aneurysm and pulmonary insufficiency (29). Bone histomorphometry and micro-computed tomography (μCT) scanning of lumbar vertebras from 3-month-old Fbn1mgR/mgR mice revealed 15% less bone content (bone volume over total volume; BV/TV), 19.7% reduction in apparent BMD (bone mineral content over TV) and decreased trabecular thickness and greater trabecular space compared with the wild-type counterparts (Fig. 1A). Trabecular number, however, was equivalent to controls (Fig. 1A). Osteopenia in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice was further correlated with increased bone resorption, as evidenced by the greater amount of urinary deoxypyridinoline (Dpd) collagen cross-links, a normal rate of bone formation (BFR), as inferred by the unremarkable pattern of dual calcein label incorporation, and an apparently normal complement of both surface osteoblasts and osteoclasts (Fig. 1B). Comparable levels of GFP fluorescence were also noted in neonatal bones of Fbn1mgR/mgR mice and wild-type littermates that harbor the pOBCol2.3GFP transgene, a marker of differentiating osteoblasts (Fig. 1C) (30). This last finding contrasts with the decrease in number of mature (GFP-positive) osteoblasts previously observed in the bones of Tsk/+;pOBCol2.3GFP mice (21).

Figure 1.

Impaired bone remodeling in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice. (A) Representative von Kossa staining and μCT images of vertebral sections from 3-month-old male wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) mice, with histograms below summarizing the measurements of BMD, BV/TV and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), number (Tb.N) and space (Tb.Sp) in WT (black) and MT (gray) samples. (B) Illustrative examples of dual-calcein labeling in tibias of 3-month-old WT and MT mice, with histograms below summarizing BFR values and osteoblast number per bone perimeter, as well as levels of urinary Dpd cross-links and osteoclast number per trabecular bone perimeter in these samples. (C) Illustrative images of GFP expression in tibial sections from newborn WT and MT mice harboring the pOBCol2.3GFP transgene. (D) Representative TRAP-stained parietal bones sections of WT and MT calvarias after LPS-induced osteolysis (bar = 50 μm); below are magnified views (×20) of the above images, with arrows pointing to TRAP-positive cells and bar graphs summarizing the relative percent of bone resorption in each sample. Error bars signify ±SD and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P<0.05) between genotypes.

Fbn1mgR/mgR mice were subject to acute stress, namely calvarial overlay of lipolysaccharide (LPS)-coated titanium particles (31), in order to resolve the apparent discrepancy between the high levels of urinary Dpd cross-links and the normal number of surface osteoclasts. Histological analyses of parietal bone sections revealed substantially more LPS-induced local osteolysis in Fbn1mgR/mgR than in wild-type mice, a finding in agreement with the collagen cross-link data reflecting an unbalanced skeletal turnover in adult Fbn1mgR/mgR mice (Fig. 1D). This acute injury test also implied the presence of an osteoclastogenic defect that was undetected by the single time-point assessment of osteoclast number during the chronic process of bone remodeling.

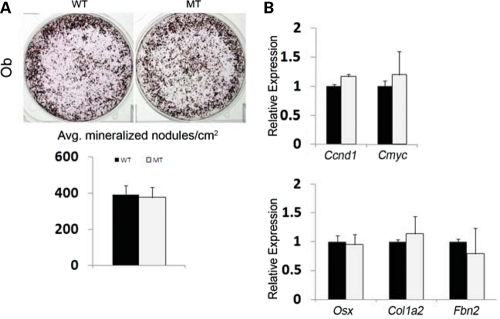

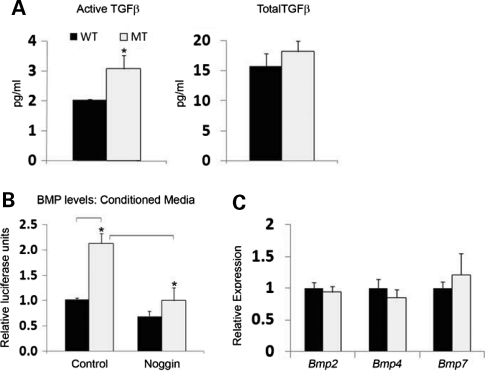

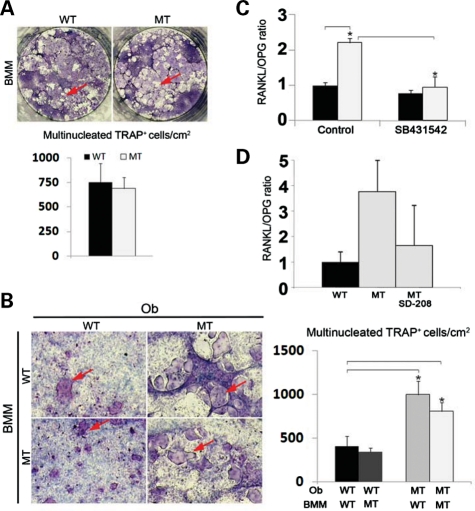

Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblasts have greater TGFβ-dependent osteoclastogenic potential

Local coupling of osteoblast and osteoclast activities is central to a physiologically balanced skeletal turnover (32). Ex vivo experiments were therefore performed to examine mutant osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and thus unravel mechanisms of defective bone resorption in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice. Consistent with the BFR data (Fig. 1B), cultured osteoblasts from wild-type and Fbn1mgR/mgR mice yielded comparable numbers of mineralized nodules and expressed similar levels of transcripts coding for key regulators of cell cycle progression and osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, normal Col1a2 expression in mutant osteoblasts was in line with normal osteogenic differentiation in Fbn1mgR/mgR; pOBCol2.3GFP bones (Fig. 1C), whereas normal Fbn2 expression ruled out a compensatory up-regulation of fibrillin-2 production in these mutant cells (Fig. 2B). Cell-based assays furthermore showed that, compared with controls, conditioned media from Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblast cultures display more TGFβ and BMP activity, which were respectively associated with normal levels of total TGFβ and Bmp transcripts (Fig. 3). These last findings supported the emerging notion that mutations in fibrillin-1 perturb ECM sequestration of both TGFβ and BMP complexes, and that enhanced BMP signaling counteracts the negative effect of increased TGFβ signaling on osteoblast maturation and bone formation (22).

Figure 2.

Normal maturation of Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblasts. (A) Illustrative von Kossa staining of calvarial osteoblasts from wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) mice cultured for 21 days after osteoinduction, with histograms below summarizing the number of mineralized nodules in each sample. (B) qPCR estimates of indicated mRNA transcripts in differentiating WT and MT osteoblast cultures. Error bars signify ±SD.

Figure 3.

Elevated TGFβ and BMP activity in mutant osteoblast cultures. (A) TMLC-based assessments of the amount of active (left) and total (right) TGFβ at day 4 of maturation of wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) osteoblast cultures. (B) C2C12BRA-based evaluation of BMP activity in conditioned media, without and with the BMP antagonist noggin, from day 4 differentiating WT and MT cultures. (C) qPCR estimates of Bmp transcripts at day 4 after osteoinduction of WT and MT osteoblast cultures. Error bars signify ±SD and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P<0.05) between genotypes and experimental samples.

Next, wild-type or Fbn1mgR/mgR bone marrow monocytes (BMMs) were grown in the presence of osteoclastogenic factors that were either administered exogenously or provided by co-cultured osteoblasts. Consistent with the lack of fibrillin expression in progenitor and differentiated osteoclasts (http://biogps.gnf.org/#goto), control and mutant BMM cultures yielded identical numbers of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive multinucleated osteoclasts (Fig. 4A). Normal numbers of TRAP-positive cells were noted in both 5- and 7-day cultures of mutant BMMs, thus excluding a potential change in the rate of osteoclast differentiation (data not shown). In contrast, osteoclastogenesis was significantly augmented when either Fbn1mgR/mgR or wild-type BMMs were co-cultured with mutant but not with control osteoblasts (Fig. 4B).The increased ability of mutant osteoblasts to promote BMM osteoclastogenesis correlated with a greater ratio than normal between the transcripts coding for the osteoclastogenic factor RANKL and the RANKL decoy OPG (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these ex vivo analyses suggested that reduced BMD in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice is largely due to enhanced osteoblast-supported osteoclast activity, and that the improper maturation of Tsk/+ osteoblasts manifests the specific outcome of this unusual Fbn1 mutation rather than the general mechanism of osteopenia in MFS (21). Additional ex vivo and in vivo experiments, respectively, documented that chemical inhibition of TGFβ receptor I (ALK5) kinase activity fully normalizes the Rankl/Opg ratio in cultured Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblasts, and reduces the higher than normal trend of the Rankl/Opg ratio in Fbn1mgR/mgR bones (Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these data implicated promiscuous TGFβ signaling as a proximal event in pathologically enhanced osteoblast-supported osteoclastogenesis in mouse models of MFS.

Figure 4.

Increased osteoclastogenic potential of mutant osteoblasts. (A) Illustrative images of wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) BMMs differentiated in the presence of pro-osteoclastogenic factors; (B) illustrative magnified images of WT or MT BMMs co-cultured with WT or MT osteoblasts (Ob). In both panels, arrows point to TRAP-positive cells and bar graphs summarize the number of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells per square centimeter in the various samples. qPCR estimates of the ratio of Rankl and Opg transcripts in (C) WT (black) and MT (white) osteoblasts cultured in the absence and in the presence of the ALK5 kinase inhibitor SB431542 and in (D) tibias from WT and MT mice systemically treated for 2 months with either vehicle or the ALK5 kinase inhibitor SD-208. Error bars represent ±SD and asterisks signify statistically significant differences (P<0.05) between genotypes and experimental samples.

Losartan improves aortic wall degeneration but not bone loss in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice

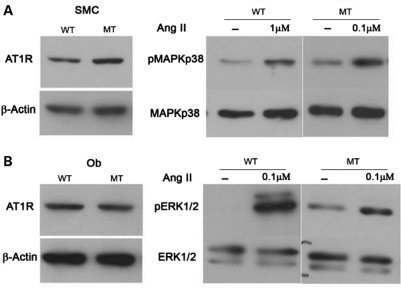

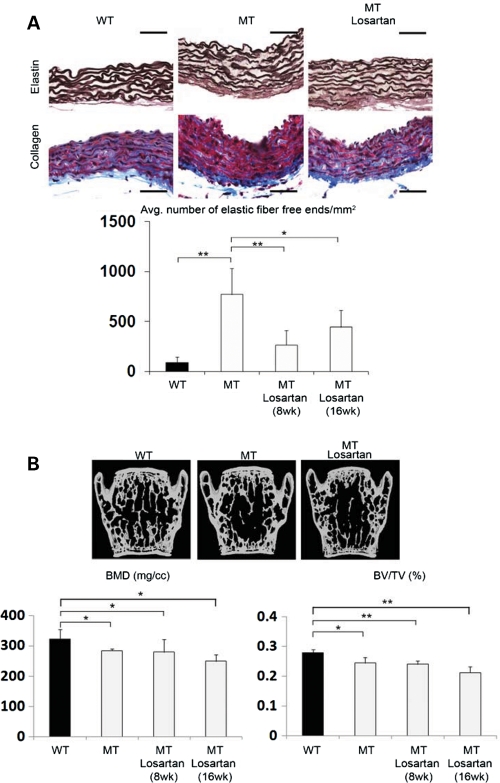

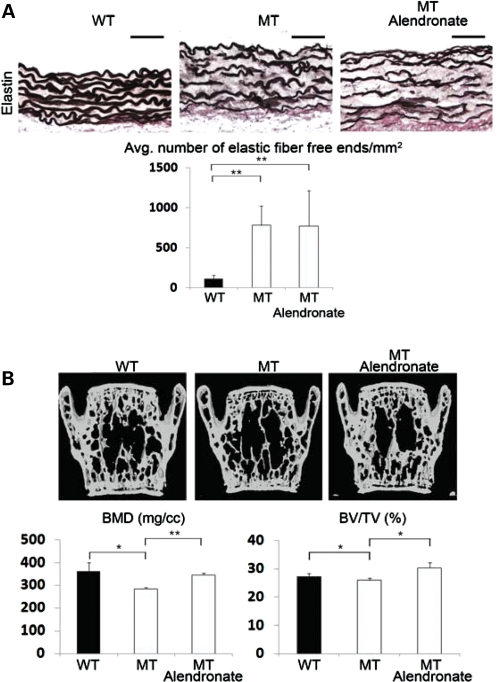

The above evidence prompted us to compare the effects of losartan and alendronate on aortic wall degeneration and loss of bone mass in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice, as the former AT1R antagonist has been shown to improve TGFβ-driven aortic aneurysm in Fbn1C1039G/+ mice and bisphosphonates such as alendronate are widely used anti-resorptive drugs that target osteoclast activity (4,33). In vitro analyses first documented the presence of comparable amounts of AT1R in mutant and control osteoblasts and aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs), in addition to confirming the receptor ability to respond to Ang II by activating p38 MAPK in SMCs and ERK1/2 in osteoblasts (Fig. 5) (34,35). The latter assays also revealed that AT1R signaling is greater and lower than controls in mutant SMCs and osteoblasts, respectively (Fig. 5). The reason of these differences was not investigated further in the present study. Next, 8-week-long treatment of Fbn1mgR/mgR mice with losartan showed a significant improvement in aortic wall architecture, but no appreciable changes in critical parameters of bone mass (Fig. 6A and B). Eight additional weeks of losartan treatment yielded nearly the same values for elastic fiber fragmentation, BMD and BV/TV as did the shorter regimen (Fig. 6A and B). In contrast, aortic enlargement in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice (21% larger vessel diameter than normal; n = 7, P<0.05) was more than halved (to 8% larger vessel diameter than controls) and nearly normalized by the 8- and 16-week-long losartan treatment, respectively (n = 8, P<0.05). As expected, systemic administration of alendronate normalized BMD and BV/TV, but had no effect on aortic wall architecture in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice (Fig. 7A and B). Collectively, these results confirmed the beneficial impact of losartan on aneurysm progression in a more severe mouse model of MFS than the one previously interrogated (4), but failed to show any significant effect on parameters of bone metabolism.

Figure 5.

Normal AT1R levels and signaling in mutant cells. Representative immunoblots of AT1R protein levels (top) in wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) vascular smooth muscle cells (SCMs) and calvarial osteoblasts (Ob) (A and B, respectively), as well as representative immunoblots of activated and inactivated MAPKs in the two WT and MT cell types that were cultured with the indicated amounts of Ang II (each set of MAPK immunoblots represents the same exposure time of WT and MT samples run together in the same gel electrophoresis).

Figure 6.

Differential effects of losartan treatment on mutant bones and aortas. (A) Illustrative images of Weigert (elastin)- or Masson trichrome (collagen)-stained cross-sections of ascending aortas from 2- and 4-month-old wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) mice untreated and treated with losartan for 8 weeks. Bar = 50 μm, and histograms below summarize the estimated number of elastic fiber free ends per millimeter square in controls and MT mice treated with losartan for 8 or 16 weeks. (B) Representative μCT scans of vertebral sections from WT and MT mice untreated and treated with losartan for 8 weeks. Histograms below summarize BMD and BV/TV values in controls and MT mice treated with losartan for 8 or 16 weeks. Whereas no significant changes in bone quality were noted in WT mice treated for 8 weeks, there was a proportional decrease in bone quality in losartan-treated WT and MT mice, perhaps indicative of the natural aging process and/or the negative impact of the drug on bone remodeling (data not shown). Error bars represent ±SD and asterisks signify statistically significant differences (*P<0.05 and **P<0.00001).

Figure 7.

Differential effects of alendronate treatment on mutant bones and aortas. (A) Illustrative images of Weigert (elastin)-stained cross-sections of ascending aortas from 3-month-old wild-type (WT) and Fbn1mgR/mgR (MT) mice untreated and treated with alendronate. Bar = 50 μm, and histograms below summarize the estimated number of elastic fiber free ends per unit surface in control and experimental samples. (B) Representative μCT scans of vertebral sections from 3-month-old WT and MT mice untreated and treated with alendronate. Histograms below summarize BMD and BV/TV values in controls and mutant mice. Consistent with the anti-resorptive properties of bisphosphonates, a proportional improvement of bone quality was also observed in WT-treated mice (data not shown). Error bars represent ±SD and asterisks signify statistically significant differences (*P<0.05 and **P<0.00001).

DISCUSSION

Several factors limit proper assessment of BMD in adult and pediatric MFS patients (12–20). As a result, the potential contribution of osteopenia to age-related complications in this condition remains uncertain and the application of bone replacement therapies is generally viewed as premature (11). Likewise, analyses of two Fbn1 mutant mouse lines have yielded conflicting data regarding the cellular mechanisms responsible for bone loss (21–23). The present study employed a strain of Fbn1 mutant mice that models progressively severe, adult lethal MFS to demonstrate that (i) increased bone resorption is the main contributor to loss of bone mass in Fbn1 mutant mice; (ii) this phenotype correlates with TGFβ-dependent stimulation of osteoblast-driven osteoclastogenesis; and (iii) losartan treatment has no beneficial impact on bone loss. Together, these findings shed new light on the pathogenesis and possible treatment of low bone density in MFS.

Normal maturation of Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblast cultures in the presence of enhanced signaling by both TGFβ and BMPs is in accordance with the notion that the relative balance, rather than the absolute amount, of these cytokines regulates the BFR by balancing the pools of progenitor and mature osteoblasts (36). In this view, perturbations of this physiological balance would lead to bone loss by either accelerating or slowing osteogenic differentiation. These considerations, together with limited information from SSS patients and Tsk/+ mice, provide a reasonable basis to speculate how different Fbn1 mutations might impact osteogenic differentiation during bone formation. SSS mutations cluster around the sole integrin-binding RGD sequence of fibrillin-1, whereas the Tsk mutation generates longer fibrillin-1 molecules with duplicated RGD sequences (21,27). Current evidence suggests that perturbed integrin-directed fibrillin-1 assembly in SSS mutations leads to excessive microfibril deposition and consequently, greater latent TGFβ concentration and signaling (25–27). The RGD duplication in Tsk fibrillin-1 may trigger the same cascade of events without however altering the ability of fibrillin-1 to regulate BMP bioavailability. In this scenario, normal and delayed maturation of Tsk/+ and Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblasts might respectively reflect unbalanced versus balanced elevation of TGFβ and BMP signaling.

Release of ECM-bound TGFβ and BMP signals also contributes to bone mass maintenance by modulating osteoclast activity directly or indirectly through osteoblast production of pro- and anti-osteoclastogenic factors (37). Our results argue for an indirect effect of heightened TGFβ signaling on bone mass maintenance in MFS. In vivo evidence includes the findings that Fbn1mgR/mgR mice excrete larger amounts of a bone degradation marker and respond more strongly to experimentally induced osteolysis. Ex vivo evidence includes the observations that Fbn1mgR/mgR osteoblasts display greater osteoclastogenic properties and higher Rankl expression. Furthermore, chemical inhibition of TGFβ signaling substantially reduces Rankl up-regulation both in mutant bones and in cultured osteoblasts. The mechanism whereby losartan lowers TGFβ signaling is unclear due to our limited understanding of Ang II-dependent and -independent AT1R signaling (38–41). In spite of human and animal evidence suggesting that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reduce the risk of bone fractures (42,43), the role of ARBs in bone metabolism remains controversial (35,44–46).

The efficacy of losartan treatment in mice with severe MFS was evaluated with respect to bone density and aortic aneurysm using a daily dose (100 mg/kg) that fulfilled the following requirements: (i) it is nearly double the maximum dose (60 mg/kg) administered to mice with milder MFS (4); (ii) it corresponds to ∼7-fold higher exposure to the active metabolite in mice than in adult humans who are treated with a daily dose of 150 mg, once these dosages are corrected for species-specific differences in drug metabolism [http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/c/cozaar/cozaar_pi.pdf (47)]; and (iii) the onset and duration of treatment are earlier and longer, respectively, than those previously used to study ARB action on rodent bone density (44). In spite of these considerations, losartan treatment was ineffective in improving osteopenia in Fbn1mgR/mgR mice. The complex interplay between TGFβ and other local and/or systemic determinants of bone homeostasis or poor bone penetration of losartan are all potential factors that may account for this negative result. Irrespectively, our results support the notion that a multifaceted treatment strategy is probably required to improve the full clinical spectrum of MFS manifestations. Along these lines, consideration should be given to the possibility that blunting TGFβ activity in MFS bones could result in unopposed high BMP signaling, which would deplete the pool of osteoprogenitors earlier than expected with negative effects on the long-term maintenance of physiological bone mass. Unlike prior studies using a milder mouse model of MFS in which losartan normalized both aortic structure and growth (4), treatment of Fbn1mgR/mgR mice showed suppression of aneurysm progression that was out of proportion to the degree of architectural protection. In this light, elastic fiber integrity (a parameter with historic focus) may be an inadequate or incomplete surrogate for aneurysm predisposition. It is also possible that inhibition of medial degeneration in severe MFS may require higher losartan dosage and/or targeting additional disease-causing events. A better understanding of the mechanisms responsible for and the phenotypic consequences of dysregulated TGFβ and/or BMP signaling will facilitate the development of comprehensive therapeutic strategies for MFS and perhaps, related disorders of the connective tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement and statistics

Mice were handled and euthanized in accordance with approved institutional and national guidelines. Triplicates of individual samples were analyzed in all experiments and statistical significance was evaluated by an unpaired t-test assuming significant association at P < 0.05, compared with control samples.

Mice and drug treatments

Fbn1mgR/mgR mice (C57BL6J genetic background) and age- and gender-matched wild-type littermates were employed (29). Transgenic mice pOBCol2.3GFP were generously provided by Dr D. Rowe and analyzed as described (30). For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) estimates of Rankl expression in vivo, mutant and wild-type mice (n = 3 animals per genotype and treatment) were systemically treated with the ALK5 inhibitor SD-208 (60 mg/kg; Tocris Biosciences) or vehicle (1% methylcellulose, Sigma-Aldrich) twice daily for 2 months. For analyses of drug efficacy on bone and vascular phenotypes, 10-day-old wild-type and mutant mice were treated for 8 or 16 weeks (n = 6 and n = 4 per genotype, respectively) with vehicle (Ora-Plus; Paddock Laboratories) or losartan (100 mg/kg/dose) by daily gavage. One-month-old wild-type and mutant mice (n = 5 per genotype) were treated for 8 weeks with vehicle (sterile phosphate-buffered saline) or alendronate (40 μg/kg/dose) by bi-weekly intraperitoneal injections. Alendronate treatment was started 20 days later than losartan to minimize inhibiting osteoclast activity during bone modeling. At the end of each drug treatment, mice were sacrificed and lumbar vertebras and ascending aortas were harvested and analyzed.

Bone μCT and histomorphometry

Formalin-fixed vertebras of wild-type and mutant mice (n ≥ 6 per genotype) were isolated and scanned using eXplore Locus SP μCT system (GE Medical Systems) with an isotropic voxel resolution of 9 μm. Scans were normalized using a density calibration phantom containing air, water and a hydroxyapatite standard (SB3; Gammex RMI) to determine BMD and BV/TV. Images were analyzed using data acquisition software (Evolver), image reconstruction software (Beam) and visualization and analysis software (Microview). A region comprising 400 transverse μCT slices, including the entire medullary volume with a border lying ∼100 μm from the cortex, was used for all analyses. Bone histomorphometry was performed on serial 7 μm-thick tissue sections (n = 6 per genotype and assay) embedded in methylmethacrylate (MMA) using a Leica microscope (Model DMLB) with the aid of the Osteomeasure analysis system (Osteometrics). MMA sections stained by von Kossa were used for independent BV/TV evaluation. Osteoblast and osteoclast number per bone perimeter (N.Ob/B.Pm; N.Oc/B.Pm) was evaluated in sections stained with toulidine blue or TRAP, respectively. BFR was evaluated in MMA sections from mice injected with 25 mg/kg calcein 10 and 2 days prior to being sacrificed. Pyrilinks-D immunoassay (Metra Biosystems) was used to evaluate Dpd cross-links in morning urine of mutant and control mice (n = 4 per genotype) and normalized to urine creatinine.

In vivo osteolysis assay

Titanium particles with adherent LPS (8 × 106 particles/μl; Johnson Matthey) or vehicle (25 μl PBS) were implanted on the surface of parietal bones of anesthetized 4-week-old WT and Fbn1mgR/mgR mice (31). Calvariae were harvested and processed for histology a week after surgery; the extent of osteolysis (percentage of resorbed bone over total bone area) was determined on TRAP-stained parietal bone sections using NIH Image J analysis software (n = 4 per genotype).

Aorta histomorphometry

Aortas were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and processed for paraffin embedding (4,27). Serial 7 μm-thick sections (n = 4 per genotype) were generated at the level where the pulmonary artery courses behind the ascending aorta and stained with the Weigert solution (elastic fibers) or Masson's trichrome solution (collagen fibers). Two individuals, blinded to the genotype, identified and counted the number of free ends along the elastic lamellae at four equal intervals in sections of the entire ring of the ascending aorta. This approach was applied to two equally distanced rings along the vessel length of each mouse. Aortas were imaged under a stereomicroscope for diameter measurement using NIH Image J software; 10 measurements of the aortic diameter were taken at equal intervals of the ascending aorta starting at the root and then averaged (4,28).

Cell culture assays

Osteogenic differentiation assays employed primary osteoblasts isolated from the calvarias of 2–4-day-old mutant and wild-type mice (n ≥ 6 per genotype) and cultured as described (31). Mineral deposits were visualized at day 21 by von Kossa staining/van Geison counter-staining and quantified using MetaMorph imaging software (Molecular Devices). For osteoclast differentiation (n = 3 per genotype), BMMs isolated from the long bones of 6–8-week-old wild-type and mutant mice were seeded on 48-well plates alone and cultured in the presence of 30 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems) and 50 ng/ml recombinant RANKL (Sigma-Aldrich), or together with primary calvarial osteoblasts under described conditions (31). Multinucleated TRAP-positive cells were counted using NIH Image J software. Total protein extracts from primary aortic SMCs and calvarial osteoblasts (n = 3 per genotype and cell type) cultured without and with 0.1 or 1 µm Ang II (Tocris Biosciences) were prepared and analyzed by western blot analysis using antibodies against AT1R (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) and phosphorylated and unphosphorylated MAPKs p38 and ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology) as described previously (48).

RNA analyses

qPCR employed 1 μg of total RNA purified from different samples or experimental conditions (n = 4 per genotype and assay) and SYBR Green Supermix with ROX (6-carboxy-X-rhodamine; Fermentas) on a Mastercycler ep Realplex instrument (Eppendorf). All qPCR primer sets were purchased from SuperArray Biosciences Corporation (β-Actin, PPM02945A; Bmp2, PPM03753A; Bmp4, PPM02998E; Bmp7, PPM03001B; Ccnd1, PPM02903E; Cmyc, PPM02924E; Col1a2, PPM04448E; Fbn2, PPM26052A; Opg, PPM03404E; Osx, PPM35999A; Rankl, PPM03047E). Thermal cycling conditions were 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles consisting of 95°C for 15 s denaturation, 60°C for 30 s annealing and 72°C for 30 s extension. Some qPCR assays (n = 3 independent assays per genotype) were also performed on RNA extracted from osteoblasts cultured for 4 days in the presence of the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 (1 μm; Sigma-Aldrich). All qPCR analyses were performed in triplicate, normalized against β-Actin mRNA and expressed relative to the indicated controls arbitrarily averaged as 1 unit.

TGFβ and BMP bioassays

Active TGFβ levels were measured in calvarial osteoblasts co-cultured with TMLC cells, whereas total TGFβ levels were measured by incubating TMLC with heat-activated conditioned media from the same osteoblasts (n = 7 per genotype and assay) (49). Both tests were carried out in reduced serum conditions (DMEM containing 0.1% BSA). Absolute amounts of TGFβ (pg/ml) were evaluated by comparing reporter gene values with luciferase units (RLU) of TMLC treated with increasing doses of rhTGFβ1 (R&D Systems). BMP bioassays were similarly carried out by measuring RLU of C2C12BRA cells incubated with osteoblast-conditioned media with or without noggin (100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) (n = 3 per genotype and assay) (50). BMP activity was expressed as relative fold of luciferase induction compared with wild-type levels arbitrarily averaged as 1 unit.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR42044 and AR49698 to F.R.) and the National Marfan Foundation. J.R.C. is a trainee in the Integrated Pharmacological Sciences Training Program supported by grant T32GM062754 from the National Institute of General Medical Studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to Dr David Rowe for supplying Col1a1 transgenic mice; we also thank Ms Maria del Solar for excellent technical assistance and Ms Karen Johnson for organizing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramirez F., Dietz H.C. Marfan syndrome: from molecular pathogenesis to clinical treatment. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007;17:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neptune E.R., Frischmeyer P.A., Arking D.E., Myers L., Bunton T.E., Gayraud B., Ramirez F., Sakai L.Y., Dietz H.C. Dysregulation of TGF-β activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:407–411. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. doi:10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng C.M., Cheng A., Myers L.A., Martinez-Murillo F., Jie C., Bedja D., Gabrielson K.L., Hausladen J.M., Mecham R.P., Judge D.P., et al. TGF-β activation contributes to pathogenesis of mitral valve prolapsed in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1586–1592. doi: 10.1172/JCI22715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habashi J.P., Judge D.P., Holm T.M., Cohn R.D., Loeys B.L., Cooper T.K., Myers L., Klein E.C., Liu G., Calvi C., et al. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science. 2006;312:117–121. doi: 10.1126/science.1124287. doi:10.1126/science.1124287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohn R.D., van Erp C., Habashi J.P., Loeys B.L., Klein E.C., Holm T.M., Judge D.P., Ramirez F., Dietz H.C. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGFβ induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nat. Med. 2007;13:204–210. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. doi:10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim D.-S., Lutucuta S., Bachireddy P., Youker K., Evans A., Entman M., Roberts R., Marian A.J. Angiotensin II blockade reverses myocardial fibrosis in a transgenic mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103:789–791. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavoie P., Robitaille G., Agharazii M., Ledbetter S., Lebel M., Lariviere R. Neutralization of transforming growth factor-β attenuates hypertension and prevents renal injury in uremic rats. Hypertens. 2005;23:1895–1903. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000182521.44440.c5. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000182521.44440.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooke B.S., Habashi J.P., Judge D., Patel N., Loeys B., Dietz H.C. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan's syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2787–2795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706585. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller J.A., Thai K., Scholey J.W. Angiotensin II receptor type I gene polymorphism predicts response to losartan and angiotensin II. Kidney Int. 1999;56:2173–2180. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00770.x. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arsenault J., Lehoux J., Lanthier L., Cabana J., Guillemette G., Lavigne P., Leduc R., Escher E. A single-nucleotide polymorphism of alanine to threonine at position 163 of the human angiotensin II type 1 receptor impairs Losartan affinity. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2010;20:377–388. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833a6d4a. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833a6d4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giampietro P.F., Raggio C., Davis J.G. Marfan syndrome: orthopedic and genetic review. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2002;14:35–41. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200202000-00006. doi:10.1097/00008480-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray J.R., Bridges A.B., Moie P.A., Pringle T., Boxer M., Paterson C.R. Osteoporosis and the Marfan syndrome. Postgrad. Med. J. 1993;69:373–375. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.811.373. doi:10.1136/pgmj.69.811.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohlmeier L., Gasner C., Marcus R. Bone mineral status of women with Marfan syndrome. Am. J. Med. 1993;95:568–572. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90351-o. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(93)90351-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohlmeier L., Gasner C., Bachrach L.K., Marcus R. The bone mineral status of patients with Marfan syndrome. J. Bone Min. Res. 1995;10:1550–1555. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101017. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tobias J.H., Dalzell N., Child A.H. Assessment of bone mineral density in women with Marfan syndrome. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1995;34:516–519. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.6.516. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/34.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Parc J.M., Plantin P., Jondeau G., Goldschild M., Albert M., Boileau C. Bone mineral density in sixty adult patients with Marfan syndrome. Osteoporos. Int. 1999;10:475–479. doi: 10.1007/s001980050257. doi:10.1007/s001980050257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter N., Duncan E., Wordsworth P. Bone mineral density in adults with Marfan syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:307–309. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.3.307. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/39.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giampietro P.F., Peterson M., Schneider R., Davis J.G., Raggio C., Myers E., Burke S.W., Boachie-Adjei O., Mueller C.M. Assessment of bone mineral density in adults and children with Marfan syndrome. Osteoporos. Int. 2003;14:559–563. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1433-0. doi:10.1007/s00198-003-1433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moura B., Tubach F., Sulpice M., Boileau C., Jondeau G., Muti C., Chevallier B., Ounnoughene Y., Le Parc J.M. Bone mineral density in Marfan syndrome. A large case–control study. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:733–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.01.026. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giampietro P.F., Peterson M.G., Schneider R., Davis J.G., Burke S.W., Boachie-Adjei O., Mueller C.M., Raggio C.L. Bone mineral density determinations by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the management of patients with Marfan syndrome-some factors which affect the measurement. HSS J. 2007;3:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s11420-006-9030-3. doi:10.1007/s11420-006-9030-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barisic-Dujmovic T., Boban I., Adams D.J., Clark S.H. Marfan-like skeletal phenotype in the tight skin (Tsk) mouse. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2007;81:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9059-4. doi:10.1007/s00223-007-9059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nistala H., Lee-Arteaga S., Smaldone S., Siciliano G., Carta L., Ono R., Sengle G., Arteaga-Solis E., Levasseur R., Ducy P., et al. Fibrillin-1 and -2 differentially modulate endogenous TGFβ and BMP bioavailability during bone formation. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:1107–1121. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nistala H., Lee-Arteaga S., Smaldone S., Siciliano G., Ramirez F. Extracellular microfibrils control osteoblast-supported osteoclastogenesis by restricting TGFβ stimulation of RANKL production. J. Biol. Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125328. 21 August 2010 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siracusa L.D., McGrath R., Ma Q., Moskow J.J., Manne J., Christner P.J., Buchberg A.M., Jimenez S.A. A tandem duplication within the fibrillin 1 gene is associated with the mouse tight skin mutation. Genome Res. 1996;6:300–313. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.4.300. doi:10.1101/gr.6.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kielty C., Rughunath M., Siracusa L.D., Sherratt J.J., Peters R., Shuttleworth C.A., Jimenez S.A. The tight skin mouse: demonstration of mutant fibrillin-1 production and assembly into abnormal microfibrils. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:1159–1166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1159. doi:10.1083/jcb.140.5.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gayraud B., Keene D.R., Sakai L.Y., Ramirez F. New insights into the assembly of extracellular microfibrils from the analysis of the fibrillin-1 mutation in the tight skin mouse. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:667–680. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.667. doi:10.1083/jcb.150.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeys B.L., Gerber E.E., Riegert-Johnson D., Iqbal S., Whiteman P., McConnell V., Chillakuri C.R., Macaya D., Coucke P.J., De Paepe A., et al. Mutations in fibrillin-1 cause congenital scleroderma: stiff skin syndrome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:23ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carta L., Pereira L., Arteaga-Solis E., Lee-Arteaga S.Y., Lenart B., Starcher B., Merkel C.A., Sukoyan M., Kerkis A., Hazeki N., et al. Fibrillins 1 and 2 perform partially overlapping functions during aortic development. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8016–8023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511599200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M511599200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira L., Lee S.Y., Gayraud B., Andrikopoulos K., Shapiro S.D., Bunton T., Jensen Biery N., Dietz H.C., Sakai L.Y., Ramirez F. Pathogenetic sequence for aneurysm revealed in mice fibrillin 1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3819–3823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3819. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalajzic I., Staal A., Yang W.P., Wu Y., Johnson S.E., Feyen J.H., Krueger W., Maye P., Yu F., Zhao Y., et al. Expression profile of osteoblast lineage at defined stages of differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24618–24626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413834200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bi Y., Nielsen K.L., Kilts T.M., Yoon A., Karsdal A.M., Wimer H.F., Greenfield E.M., Heegaard A.M., Young M.F. Biglycan deficiency increases osteoclast differentiation and activity due to defective osteoblasts. Bone. 2006;38:778–786. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teitelbaum S.L. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reszka A.A., Rodan G.A. Mechanism of action of bisphosphonates. Curr. Osteopor. Res. 2003;1:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s11914-003-0008-5. doi:10.1007/s11914-003-0008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Touyz R.M., He G., El Mabrouk M., Schiffrin E.L. p38 Map kinase regulates vascular smooth muscle cell collagen synthesis by angiotensin II in SHR but not in WKY. Hypertension. 2001;37:574–580. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu H., Nakagami H., Osako M.K., Hanayama R., Kunugiza Y., Kizawa T., Tomita T., Yoshikawa H., Ogihara T., Morishita R. Antiotensin II accelerates osteoporosis by activating osteoclasts. FASEB J. 2008;22:2465–2475. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-098954. doi:10.1096/fj.07-098954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeda S., Hayashi M., Komiya S., Imamura T., Miyazono K. Endogenous TGFβ signaling suppresses maturation of osteoblastic mesenchymal cell. EMBO J. 2004;23:552–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600067. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alliston T., Piek E., Derynck R. TGF-β family signaling in skeletal development, maintenance and disease. In: Derynck R., Miyazono K., editors. The TGFβ Family. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. pp. 667–723. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Vita J., Sanchez-Lopez E., Esteban V., Ruperez M., Egido J., Ruiz-Ortega M. Angiotensin II activates the Smad pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells by a transforming growth factor-β-independent mechanism. Circulation. 2005;111:2509–2417. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165133.84978.E2. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000165133.84978.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang F., Chung A.C., Huang X.R., Lan H.Y. Angiotensin II induces connective tissue growth factor and collagen I expression via transforming growth factor-β-dependent and -independent Smad pathways: the role of Smad3. Hypertension. 2009;54:877–884. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136531. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zou Y., Akazawa H., Qin Y., Sano M,, Takano H., Minamino T., Makita N., Iwanaga K., Zhu W., Kudoh S., et al. Mechanical stress activates angiotensin II type 1 receptor without the involvement of angiotensin II. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:499–506. doi: 10.1038/ncb1137. doi:10.1038/ncb1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rakesh K., Yoo B., Kim I.M., Salazar N., Kim K.S., Rockman H.A. β-arrestin-biased agonism of the angiotensin receptor induced by mechanical stress. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000769. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynn H., Kwok T., Wong S.Y., Woo J., Leung P.C. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor use is associated with higher bone mineral density in elderly Chinese. Bone. 2006;38:584–588. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu H., Nakagami H., Osako M.K., Nakagami F., Kunugiza Y., Tomita T., Yoshikawaka H., Rakugi H., Ogihara T., Morishita R. Prevention of osteoporosis by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in spontaneous hypertensive rats. Hypertens. Res. 2009;32:786–790. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.99. doi:10.1038/hr.2009.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Broulik P.D., Tesar V., Zima T., Jirsa M. Impact of antihypertensive therapy on the skeleton: effects of enalapril and AT1 receptor antagonist losartan in female rats. Physiol. Res. 2001;50:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izu Y., Mizoguchi F., Kawamata A., Hayata T., Nakamoto T., Nakashima K., Inagami T., Ezura Y., Noda M. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor blockade increases bone mass. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4857–4864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.A807610200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807610200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y.Q., Ji H., Shen Y., Ding L.J., Zhuang P., Yang Y.L., Huang Q.J. Chronic treatment with angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonists reduced serum but not bone TGFβ1 levels in ovariectomized rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009;87:51–55. doi: 10.1139/Y08-097. doi:10.1139/Y08-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konstam M.A., Neaton J.D., Dickstein H., Drexel H., Komajada M., Martinez F.A., Riegger G.A.J., Malbecq W., Smith R.D., Guptha S., et al. Effects of high-dose versus low-dose losartan on critical outcomes in patients with heart failure (HEAAL study): a randomized, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1840–1848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61913-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carta L., Smaldone S., Zilberberg L., Loch D., Dietz H.C., Rifkin D.B., Ramirez F. p38 MAPK is an early determinant of promiscuous Smad2/3 signaling in the aortas of fibrillin-1 (Fbn1)-null mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:5630–5636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806962200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M806962200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abe M., Harpel J.G., Metz C.N., Nunes I., Loskutoff D.J., Rifkin D.B. An assay for transforming growth factor-β using cells transfected with a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter-luciferase construct. Anal. Biochem. 1994;216:276–284. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1042. doi:10.1006/abio.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zilberberg L., ten Dijke P., Sakai L.Y., Rifkin D.B. A rapid and sensitive bioassay to measure bone morphogenetic protein activity. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-41. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]