Abstract

Background

The Turkish population living in the Netherlands has a high prevalence of psychological complaints and has a high threshold for seeking professional help for these problems. Seeking help through the Internet can overcome these barriers. This project aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a guided self-help problem-solving intervention for depressed Turkish migrants that is culturally adapted and web-based.

Methods

This study is a randomized controlled trial with two arms: an experimental condition group and a wait list control group. The experimental condition obtains direct access to the guided web-based self-help intervention, which is based on Problem Solving Treatment (PST) and takes 6 weeks to complete. Turkish adults with mild to moderate depressive symptoms will be recruited from the general population and the participants can choose between a Turkish and a Dutch version. The primary outcome measure is the reduction of depressive symptoms, the secondary outcome measures are somatic symptoms, anxiety, acculturation, quality of life and satisfaction. Participants are assessed at baseline, post-test (6 weeks), and 4 months after baseline. Analysis will be conducted on the intention-to-treat sample.

Discussion

This study evaluates the effectiveness of a guided problem-solving intervention for Turkish adults living in the Netherlands that is culturally adapted and web-based.

Trial Registration

Nederlands Trial Register: NTR2303

Background

Historically, the Netherlands has played an important role in Europe as a host country for immigrants. The immigration of guest workers became an important trend after World War II and changed the Netherlands into a multi-ethnic and multicultural society. Nowadays, almost one-fifth (19.9%) of the Dutch population was born outside the Netherlands (first generation migrants) or has one or both parents born outside the Netherlands (second generation migrants) [1]. Slightly more than half of these migrants (55%) come from non-western countries. The Turkish population is one of the main ethnic groups in Dutch society and constitutes 2.3% of the total population. About half of this group was born in Turkey (first generation), while the other half has parents who were born in Turkey (second generation). Migration is a complex process, which can have a immense impact on a migrant's life and mental health. It can improve the quality of life of migrants in the economic sense, but it can also involve complexities in the adjustment process, such as unemployment, minority status and tensions between generations [2].

One-third of the Turkish population living in the Netherlands has psychological problems such as depression and anxiety, which is a higher prevalence than normally found in general population studies [2]. The 1-month prevalence of depressive and/or anxiety disorders is highest among the Turkish migrant group (18.7%) in comparison with other ethnic groups (6.6% among Dutch and 9.8% among Moroccan) [3].Turkish women in particular currently have a strongly increased risk for developing depression compared to Dutch natives, and young Turkish women are at a high risk of attempting suicide [4].Despite the high risk of serious psychological problems among the Turkish population, they benefit to a much lesser extent from advances in evidence-based depression prevention services than the general population. Their mental health care service uptake is low and they often have a high threshold for seeking professional help for their mental health problems [5,6].

An innovative way to overcome the barriers referred to above is the Internet, which has low threshold acceptability, a high level of anonymity and offers flexibility in time and place. There is now convincing evidence that web-based interventions effectively reduce depressive symptoms and prevent depression [7-12] and they have been shown to be not only clinically effective, but also cost effective [13]. Little is known, however, about the effectiveness of these interventions in ethnic minority groups, although expectations are that these groups may also benefit from the interventions. Self-help through the Internet has the main advantage of a high level of anonymity and might overcome important cultural barriers. Since almost 80% [14] of the Turkish population in the Netherlands has internet access, it could be an ideal way of reaching and offering help to Turkish people with depressive symptoms.

One successful example of an evidence-based intervention is Alles Onder Controle (AOC). This is a web-based guided treatment defined as a standardized psychological intervention, which can be worked through independently by the clients themselves in their own homes. The clients receive weekly feedback from a trained coach by e-mail. AOC has a self-examination framework [15] and is based on problem-solving therapy, the core element being that clients learn to regain control over their problems and lives in a structured way. This method has been proven to be effective in several studies [16,17] and the statistical and clinical effectiveness of AOC in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety among native Dutch have been shown in several studies [11,18]. It is still unknown, however, whether this intervention is also effective among ethnic groups, especially among the Turkish population, which is currently a high risk group for developing depression. No previous attempts have been made to adjust and examine AOC for Turkish migrants, although the limited studies available on depression interventions in other countries show that ethnic minorities can be effectively recruited and treated with prevention interventions [19-22].

In the present study, we will work with AOC-TR, the culturally adapted version based on the needs of the Turkish population that is available in Dutch and in Turkish. This online guided self-help intervention is intended to reduce depression complaints and the effectiveness of AOC-TR will be examined in a randomized controlled trial with adult Turkish people living in the Netherlands.

Methods

Study design

This study is a randomized controlled trial with two arms: an experimental group and a wait list control group. The experimental group obtains direct access to the guided web-based self-help intervention; the wait list control group receives access to the intervention after 4 months. The study protocol, information brochure and informed consent have been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Turkish adults living in the Netherlands are eligible if they meet the following criteria: 1) age 18 years or older; 2) depressive symptoms (measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale, CES-D score ≥ 16); 3) Turkish background (participant was born in Turkey or at least one of his/her parents was born in Turkey); 4) has access to a PC and the Internet and an e-mail address. Participants will be excluded if they are suicidal (according to the MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview).

Recruitment

Recruitment will take place among the Turkish population in the Netherlands by means of advertisements in Dutch and Turkish national newspapers, magazines, community sites, and banners on health related websites for migrants. These advertisements contain a link to the research website with information about the study. Respondents who are interested can apply by sending an e-mail to the researcher. The information brochure and informed consent will be e-mailed together with the link for the screening.

Randomization

After screening, participants will be randomized into one of the two conditions: the experimental group and wait list control group. The allocation schedule will be generated by an independent researcher using a computerized system. Those in the experimental condition will receive a username and password to log in to AOC-TR. Participants who are in the wait list condition will receive the same schedule of assessments online as the people in the experimental condition and receive a username and password to log in to the treatment after four months.

Sample size

The sample size will be based on the expected difference of d = 0.45 on the primary outcome between the experimental and control groups. This expected difference is based on previous studies [10,11]. Based on a power (1-beta) of 0.80 in a two-tailed test, an alpha of 0.05, we need to start with 100 participants at baseline in each condition to show an effect-size of 0.45. The total sample size at baseline therefore, is determined as being 200 participants with depressive complaints.

Interventions

Problem-Solving Treatment

The Dutch version of Alles Onder Controle has been adapted by:

- cultural sensitivity in the languages and presentation in relation to psychological problems

- use of culture-specific cases and problems that are recognizable for the target group concerned

- culture-specific examples of persons with similar problems

The intervention was translated into Turkish by a Turkish psychologist after adaptation and the translation was checked by two native speakers. Each participant is allowed to choose his/her language of preference.

The intervention consists of 5 sessions and takes 5 weeks in total. During that period the respondents indicate what they think is important in their lives, they make a list of their "problems and worries" and they categorize their problems into three groups: unimportant (not related to what they think is important in their lives), important and solvable (these problems are solved by a systematic problem-solving approach consisting of 6 steps), or important but unsolvable (having lost someone through death or having a chronic general medical disease for example; in the case of problems like these, they make a plan for how to live with them). The 6-step problem-solving procedure is the core of the intervention and people are stimulated to use this procedure during the course for several of their 'important and solvable' problems. The idea is that by mastering this technique people will regain mastery of their problems and ultimately their lives. At the end, participants will receive a certificate for completing the intervention.

Support

The participants are supported by trained coaches, whose feedback on the homework assignments done by the participants is given in brief weekly e-mails. The total amount of time spent on each participant is about 1.5 hours. It takes about 15 or 20 minutes per week per respondent to write these e-mails, which will be done by a bi-lingual psychologist at the VU University. The researcher (BU) will verify whether the coach has followed the treatment protocol sufficiently by reading a selection of the emails and by supervision.

Assessments

All assessments will take place in the preferred language, either Dutch or Turkish. The primary outcome measure is the reduction of depression symptoms as measured by the CES-D, the secondary outcome measures are symptoms of anxiety, somatic symptoms, acculturation, quality of life and satisfaction.

The CES-D, one item on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Section C of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I) will be administered as screening measures. Suicide ideations and risk will be measured in two steps. Suicide ideations and risk will be measured in two steps. First, the suicide item on the BDI-II will be presented [23,24]. This instrument is validated among Dutch (e.g. [25,26]] and Turkish populations [27,28]. If the response is confirming, then the suicide risk will be measured with the suicidality section of the MINI [29,30]. The suicide section of the MINI consists of six items and quantifies respondents in four groups: no suicide risk, low suicide risk, moderate suicide risk and high suicide risk. Dutch [31] and Turkish [32] translations of the MINI will be used.

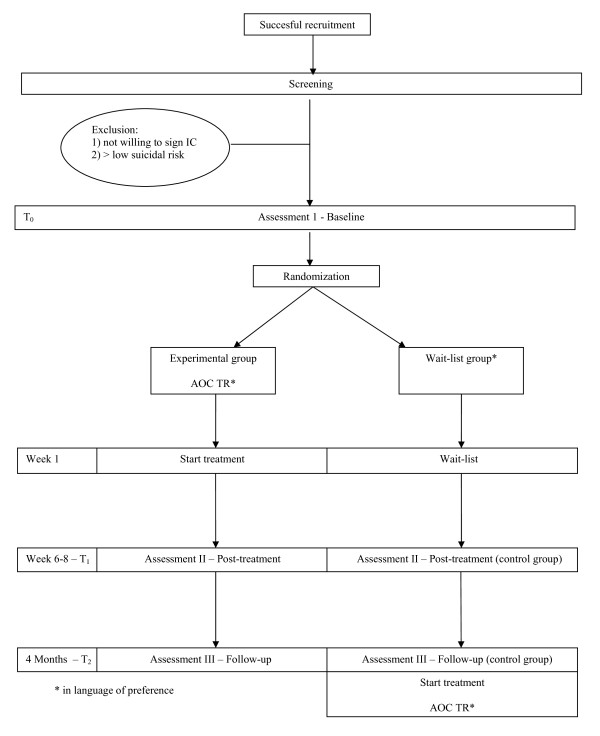

Assessments will take place before randomization (T0), after completing the treatment (6-8 weeks, T1), and four months after baseline (T2). An overview of the procedures the participants will undergo in this study is given in Figure 1. See table 1 for an overview of all assessments at each point in time.

Figure 1.

Research procedure in flow diagram.

Table 1.

Overview of instruments per measurement.

| Number of items |

T0 (baseline) |

T1 (6-8 weeks) |

T2 (4 months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Socio-demographic data | 10 | x | ||

| 2. Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | 20 | x | x | x |

| 3. Anxiety (scale of HADS) | 7 | x | x | x |

| 4. Somatic symptoms (scale of SCL-90) | 12 | x | x | x |

| 5. Acculturation (LAS) | 28 | x | x | x |

| 6. Quality of life (EuroQol 5D) | 5 | x | x | x |

| 7. Satisfaction and track and trace | 5 | x | x | |

Instruments

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms will be measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale (CES-D) [33]. It includes 20 self-rated items, each scored 0-3, and measures the severity of depression. The total score ranges from 0 (no feelings of depression) to 60 (severe symptoms of depression. The CES-D is available in Dutch and Turkish and both have been proven to have good psychometric properties in terms of validity and reliability [34,35]. The CES-D is also reliable and valid when presented digitally [36]. The optimal cut-off score varies in literature, but a score of 16 is usually regarded as indicating clinically relevant depressive symptoms [37].

Anxiety

The Anxiety scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) will be used to measure symptoms of anxiety [38]. The HADS consists of a depression scale and an anxiety scale with a total of 14 items. Each item can be scored with a 4-point Likert scale on a range of 0-3, where 0 refers to no anxiety and 3 to high anxiety. The total score range is 0-21. A score between 0 and 7 indicates no anxiety; a score between 8 and10 indicates possible anxiety; scores above 11 or12 are indicative of a clinical anxiety disorder. The HADS has been proven to be a valid and reliable instrument in various normal and clinical Dutch samples [39,40] and in Turkish samples [41].

Somatic symptoms

The Somatization (SOM) subscale on the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) will be used for measuring somatic symptoms [42]. This is a five-point rating scale containing 12 items. Dutch and Turkish translations will be used for this study [43,44].

Acculturation

The Lowlands Acculturation Scale (LAS) will be used to measure the degree of acculturation [45,46]. It consists of 25 items that are rated on 6-point Likert-type scales with the extremes labelled as 'totally disagree' and 'totally agree'. The LAS can be divided into 5 subscales: Skills, Traditions, Social Integration, Values and Norms, and Feelings of Loss. The official Dutch and Turkish translations will be used, both of which have been validated [45].

Quality of life

The quality of life will be measured by the EuroQol Questionnaire (EQ5D) [47] in the official Dutch and Turkish translations, both of which have been validated [48-50]. This instrument consists of 5 items (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), each of which is rated as causing "no problems", "some problems", or "extreme problems". The score per item ranges from 0 (poor health) to 1 (perfect health).

Satisfaction and Track and Trace

A track and trace system will keep a record of the dates the participant logs on or finishes a lesson, and the number of e-mails sent to and received by the coach. This system will also ask the question "Was this lesson useful to you?" in Dutch and Turkish after each lesson and the answer can be given on a 5-point Likert scale.

Statistical analysis

The study will be carried out in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines. All analyses will be based on the intention-to-treat sample and missing values will be imputed by means of regression analyses. A t-test will be used to compare the post-test mean scores (at T1 and T0) for the intervention group with the post-test mean scores for the control group. For comparison of the two means Cohen's d will be used as the between effect size. Cohen's d will be calculated as the difference between the post-test mean scores of the intervention and the control group divided by the pooled standard deviation. Effect sizes of 0.8 are assumed to be large; effect sizes of 0.5 are moderate; and effect sizes of 0.2 are assumed to be small [51].

Discussion

A substantial part of the Dutch population has a Turkish background. They have a high prevalence of mental health disorders and have a high threshold for seeking professional help for these problems, but providing psychological help through the Internet may lower this threshold. This study evaluates the effectiveness of a guided self-help problem-solving intervention for depressed Turkish migrants that is culturally adapted and web-based. The strengths and limitations of the study can be summarized as follows:

Much is still not known about the effectiveness of internet interventions for depression in ethnic groups. By examining the effectiveness of a problem-solving treatment on the Internet for Turkish adults in the Netherlands, important information about psychological treatments in an ethnic minority group will be gathered. This will be highly relevant for clinicians and mental health services in improving the quality and the effectiveness of offering professional help.

A second strength of this study is that the intervention is available in two languages, which provides the flexibility of choosing the language of preference for receiving professional help. Turkish migrants who were previously unable to seek help because of the language barrier can now be treated. Moreover, by using the Internet to offer help, those who have a high threshold for seeking help can be reached and benefit from the treatment.

Another strength of this study is that the assessments will be carried out in two languages, while most other studies exclude non-Dutch speakers. All questionnaires used have been validated in both languages.

There are some limitations, however, that are worthwhile mentioning. First of all, we are unable for practical reasons to perform lengthy and costly diagnostic interviews, which means that we will not know how many participants in our study met the DSM criteria for depression. The results will, however, reflect the population whose symptoms are so distressing that they are willing to seek help. Secondly, the psychometric validities of the questionnaires used in this study have not yet been tested in an online environment.

Abbreviations

AOC: Alles Onder Controle; AOC-TR: Alles Onder Controle TR (Adapted version); CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale; M.I.N.I.: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory II; SOM: Somatization (subscale on the SCL-90-R); SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; LAS: Lowlands Acculturation Scale; EQ 5D: EuroQol Questionnaire 5D.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the design of this study. PC and AvS made the Internet-based PST intervention, AOC and BÜ adapted the intervention for the Turkish population. BÜ drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the further writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Burçin Ünlü, Email: b.unlu@psy.vu.nl.

Heleen Riper, Email: hriper@trimbos.nl.

Annemieke van Straten, Email: a.van.straten@psy.vu.nl.

Pim Cuijpers, Email: p.cuijpers@psy.vu.nl.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the VU University and the Trimbos-institute, the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction.

References

- CBS, Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=37296ned&D1=a&D2=0,10,20,30,40,50,(l-1)-l&HD=100428-1217&HDR=G1&STB=T

- Desjarlais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, Kleinman A. World Mental Health, problems and priorities in low-income countries. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit MAS, Tuinebreijer WC, Dekker J, Beekman AJTF, Gorissen WHM, Schrier AC, Penninx BWJH, Komproe IH, Verhoeff AP. Depressive and anxiety disorders in different ethnic groups A population based study among native Dutch, and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese migrants in Amsterdam. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43:905–912. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen D, Smit JH, van Balkom AJLM, Saharso S. Suicidal behaviour of young immigrant women in the Netherlands. Can we use Durkheim's concept of 'fatalistic suicide' to explain their high incidence of attempted suicide? Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2009;32:302–322. doi: 10.1080/01419870802315043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilderink I, van't Land H, Smits C. Trendrapportage 2009. Drop-out onder allochtone GGZ-cliënten. Themarapportage. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbea N, Smits C, Franx G. Wie kiespijn heeft, zoekt zelf een arts. Informatiebehoeften van Turkse en Marokkaanse cliënten met depressie. Vol. 5. Cultuur, migratie Gezondheid; 2008. pp. 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, Lindefors N. Effects of Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety and mood disorders. Psychiatry. 2007;2:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- van't Hof E, Cuijpers P, Stein DJ. Self-Help and Internet-Guided Interventions in Depression and Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses. Cns Spectrums. 2009;14:34–40. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900027279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2007;37:319–328. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek V, Nyklicek I, Smits N, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop VJM. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for sub-threshold depression in people over 50 years old: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1797–1806. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmerdam L, Van Straten A, Twisk J, Riper H, Cuijpers P. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e44. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf LE, Gerhards S, Evers S, Arntz A, Riper H, Severens J, Widdershoven G, Metsemakers J, Huibers M. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression in primary care: Design of a randomised trial. Bmc Public Health. 2008;8:224–0. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards SAH, de Graaf LE, Jacobs LE, Severens JL, Huibers MJH, Arntz A, Riper H, Widdershoven G, Metsemakers JFM, Evers SMAA. Economic evaluation of online computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy without support for depression in primary care: randomised trial. The British Journal Of Psychiatry: The Journal Of Mental Science. 2010;196:310–318. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foquz Etnomarketing. http://www.foquz.nl/etnomarketing/persberichten/internet10-03-2008.html

- Bowman D, Scogin F, Lyrene B. The efficacy of Self-Examination Therapy and Cognitive Bibliotherapy in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Psychotherapy Research. 1995;5:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman V, Ward LC, Bowman D, Scogin F. Self-examination therapy as an adjunct treatment for depressive symptoms in substance abusing patients. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd M, McKendree-Smith N, Bailey E. Two-year follow-up of self-examination therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Anx Dis. 2002;16:369–375. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N. Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2008;10 doi: 10.2196/jmir.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz R. Prevention of depression with primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:199–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02506936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Brenneman DL. In: Handbook on Ethnicity, Aging, and Mental Health. Volume 1995. 1. Pagett DK, editor. Westport: Greenwood Press; 1995. Chronic disease among older American Indians: Preventing depressive symptoms and related problems of coping; pp. 284–303. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló J, Bernal G, Rivera-Medina C. Individual and group CBT and IPT for Puerto Rican adolescents with depressive symptoms. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:234–245. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz R, Lenert L, Delucchi K, Stoddard J, Perez J, Penilla C, Perez-Stable E. Toward evidence-based Internet interventions: A Spanish/English Web site for international smoking cessation trials. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:77–87. doi: 10.1080/14622200500431940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zitman FG, Griez EJL, Hooyer C. Standaardisering depressievragenlijsten. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 1989;31:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does AJW. BDI-II-NL. Handleiding. De Nederlandse versie van de Beck Depression Inventory. 2. Lisse: Harcourt Test Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hisli N. Beck depresyon envanterinin geçerliliği üzerine bir çalışma. Psikoloji Dergisi. 1988;22:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Uslu R, Kapçı EG, Öncü B, Uğurlu M, Türkçapar H. Psychometric properties and cut-off scores of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Turkish adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2008;15:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9122-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH. et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–231. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet IIM, de Beurs E. Het MINI internationaal Neuropsychiatrisch Interview (MINI) Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie. 2007;49:393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeler A. In: MİNİ Uluslararası Nöropsikiyatrik Görüşme Türkçe Uyarlama 5.0.0. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, editor. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychol Measur. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997;27:231–235. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijker J, van der Wurff FB, Poort EC, Smits CHM, Verhoeff AP, Beekman ATF. Depression in first generation labour migrants in Western Europe: the utility of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19:538–544. doi: 10.1002/gps.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker T, van Straten A, Marks I, Cuijpers P. A brief Web-based screening questionnaire for common mental disorders: development and validation. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e19. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haringsma R, Engels GI, Beekman ATF, Spinhoven P. The criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of self-referred elders with depressive symptomatology. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:558–563. doi: 10.1002/gps.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psych med. 1997;27:363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydemir O, Guvenir T, Kuey L, Kultur S. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of Hospital anxiety and depression scale (in Turkish) Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 1997;8:280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Symptoms Checklist 90-R Administration, Scoring Procedures Manual. 3. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arrindell WA, Ettema JHM. Symptom checklist. Handleiding bij een multidimensionele psychopathologie-indicator. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aksaray G, Kortan G, Erkaya H, Yenilmez Ç, Kaptanoğlu C. Gender differences in psychological effect of the August 1999 earthquake in Turkey. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;60:387–391. doi: 10.1080/08039480600937553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooren T, Knipscheer J, Kamperman A, Kleber R, Komproe IH. In: The impact of war. Studies on the psychological consequences of war and migration. Mooren T, editor. Delft: Eburon Publishers; 2001. The Lowlands Acculturation Scale. Validity of an Adaptation Measure Among Migrants in the Netherlands; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kamperman AM, Komproe IH, de Jong JTVM. Migrant mental health: a model for indicators of mental health and health care consumption. Health Psychology: Official Journal Of The Division Of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2007;26:96–104. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1996;37:53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Annals Of Medicine. 2001;33:337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers LM, Stalmeier PFM, McDonnell J, Krabbe PFM, van Busschbach JJ. Measuring the quality of life in economic evaluations: the Dutch EQ-5D tariff. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde. 2005;149:1574–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eser E, Dinç G, Cambaz S. 2. Sağlıkta Yaşam Kalitesi Kongresi: 5-7 April 2007; Izmir. Izmir: Bildiri Özetleri Kitabı Meta Basımevi; 2007. EURO-QoL (EQ-5D) indeksinin toplum standartları ve psikometrik özellikleri: Manisa kent toplumu örneklemi; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]