Abstract

Objectives: NHS North West aimed to fully implement the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) 1 year ahead of the August 2009 national deadline. Significant debate has taken place concerning the implications of the EWTD for patient safety. This study aims to directly address this issue by comparing parameters of patient safety in NHS North West to those nationally prior to EWTD implementation, and during ‘North West-only’ EWTD implementation.

Design: Hospital standardised mortality ratio (HSMR), average length of stay (ALOS) and standardised readmission rate (SRR) in acute trusts across all specialties were calculated retrospectively throughout NHS North West for the three financial years from 2006/2007 to 2008/2009. These figures were compared to national data for the same parameters.

Results: The analysis of HSMR, ALOS and SRR reveal no significant difference in trend across three financial years when NHS North West is compared to England. HSMR and SRR within NHS North West continued to improve at a similar rate to the England average after August 2008. The ALOS analysis shows that NHS North West performed better than the national average for the majority of the study period, with no significant change in this pattern in the period following August 2008. When the HSMRs for NHS North West and England are compared against a fixed benchmark year (2005), the data shows a continuing decrease. The NHS North West figures follow the national trend closely at all times.

Conclusions: The data presented in this study quantitatively demonstrates, for the first time, that implementation of the EWTD in NHS North West in August 2008 had no obvious adverse impact on key outcomes associated with patient safety and quality of care. Continued efforts will be required to address the challenge posed nationally by the restricted working hour’s schedule.

Introduction

Since August 2009, doctors in training in the UK have been required by law to work an average of no >48 h/week, calculated over a 26 week reference period. The legislation underpinning this originated from Europe in 1993 and was originally termed the European Working Time Directive (EWTD). This directive was incorporated into UK law in 1998 under the Working Time Regulations (WTR) and the restriction of doctors’ working hours was gradually implemented, allowing an incremental reduction to 48 h by August 2009.

There has been significant debate concerning the implications of the EWTD for patient safety and junior doctor training. Although the initial intention in applying this legislation was to improve patient and doctor safety through reduction in working hours, concerns regarding the threat to quality of training, service provision and continuity of care have been aired with regularity. Alongside this, the implicit concern that patient safety could be adversely affected has received widespread press coverage.1–4 However, there is no robust evidence to uphold the viewpoint that the adoption of a restricted working hours schedule will impair patient safety, directly or indirectly.

Conversely, there is a body of evidence to support the reduction in doctors working hours with reference to improving patient safety and reducing serious medical error. A number of studies conducted in the USA in recent years provide evidence for increased serious medical error in those working prolonged shifts compared with those undertaking restricted hours.5,6 Similarly, an incremental increase in adverse patient safety incidents with successive prolonged shifts, especially night-shifts, has been well demonstrated.7 The Royal College of Physicians Multidisciplinary Working Group published guidance in 2006 which recommended the cessation of traditional full-shift working practises involving blocks of seven 13-h night-shifts, and endorsed a limit of four successive night-shifts that should be minimized in length where possible.8 A prospective study, recently undertaken in the UK, has demonstrated a marked decrease in medical error rates amongst doctors working in an EWTD compliant rota when directly compared to a group undertaking a traditional 56 h/week working pattern.9 Moreover, the 2009 postgraduate medical education and training board (PMETB) national survey of trainees provides evidence that trainees operating within the 48-h limit are significantly less likely to report serious error.10

The EWTD was not the first move to restrict working hours for junior doctors; the New Deal junior doctor contract, agreed in 1991, stipulated maximum shift lengths, maximum weekly working hours (depending on shift type) and outlined minimum rest requirements.11 This contract embodied the viewpoint that junior doctors, alongside other workers, were entitled to adequate work/life balance and epitomized the wider perspective that ‘tired doctors are not safe doctors’.12

The actual implementation of an average 48-h working week represented a significant challenge to the organization and provision of clinical services across the country; in recognition of this, and in order to lead the way in EWTD implementation, NHS North West undertook a project which aimed to implement the EWTD 1 year ahead of the August 2009 deadline.13

Although there is now an accumulation of evidence to support the viewpoint that patient safety is improved by restricted working hours amongst doctors, there are no objective UK data examining quantitative parameters of patent safety in an environment where the EWTD limit has been implemented. The unique circumstances existing in the UK from August 2008 allow us to compare the performance of a largely EWTD compliant region (NHS North West) to the rest of England, which had not yet implemented the 48-h limit. These circumstances allow us to test the hypothesis that implementation of the EWTD in the North West has had no adverse impact on several key outcomes associated with patient safety.

This study aims to compare parameters of patient safety in NHS North West to those nationally, prior to EWTD implementation, and after ‘North West-only’ EWTD implementation. In devising this study, we considered hospital standardised mortality ratio (HSMR), average length of stay (ALOS) and standardised readmission rate (SRR) in acute trusts, across all specialties, to be suitable quantitative indicators of patient safety and quality of care.14–16

Methods

Data for this study were collected and analysed by Dr Foster Intelligence. The information is based on the data which is routinely collected from day case and inpatient records throughout the NHS. These data were then extracted for analysis by the Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College London through the secondary users service (SUS). The data were cleaned and anonymized according to established hospital episode statistics (HES) guidelines. HSMR, ALOS and SRR across NHS North West were analysed retrospectively for the three financial years 2006/2007 to 2008/2009 (effectively April 2006 to March 2009). These figures were compared with the national data for the same parameters. No individual patients were identifiable in this study.

The HSMR compares the number of expected deaths with the number of actual deaths in a ratio [(observed deaths/expected deaths) × 100.] The HSMR analysis was performed for acute trusts only, across all specialties. The expected counts are derived using logistic regression and are adjusted for factors to indirectly standardize for difference in case mix, including: (i) sex, (ii) age group (in 5 year bands up to ≥90), (iii) method of admission (non-elective or elective), (iv) the socio-economic deprivation quintile of the area of residence of the patient (based on the Carstairs Index),17 (v) primary diagnosis (based on the Clinical Classification System), (vi) co-morbidities (based on Charlson Score),18 (vii) number of previous admissions, (viii) month of admission (for certain conditions where seasonal variation may be important, e.g. respiratory infection) and (ix) whether a patient is being treated within the specialty of palliative care.

A published methodology for calculation of HSMRs was utilized; however, a detailed description of this methodology is beyond the scope of this article and can be found in our references.19

ALOS analysis measures the average duration of all patient episodes in hospital across acute trusts, across specialties, from the day of admission to the day of discharge, divided into elective and non-elective groups.

The SRR analysis takes into account the number of emergency readmissions to acute trusts across specialties within 28 days of discharge, where readmission was not part of the planned treatment. The rate is calculated by dividing the observed readmissions by the expected readmissions. Both are indirectly standardized for the following factors: (i) age on admission (in 5 year bands up to ≥90) (ii) sex, (iii) admission method (non-elective or elective), (iv) socio-economic deprivation quintile of the area of residence of the patient (based on the Carstairs Index), (v) primary diagnosis (based on the Clinical Classification System), (vi) co-morbidities (based on Charlson Score) and (vii) year of discharge (financial year).

Results

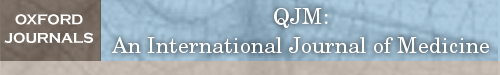

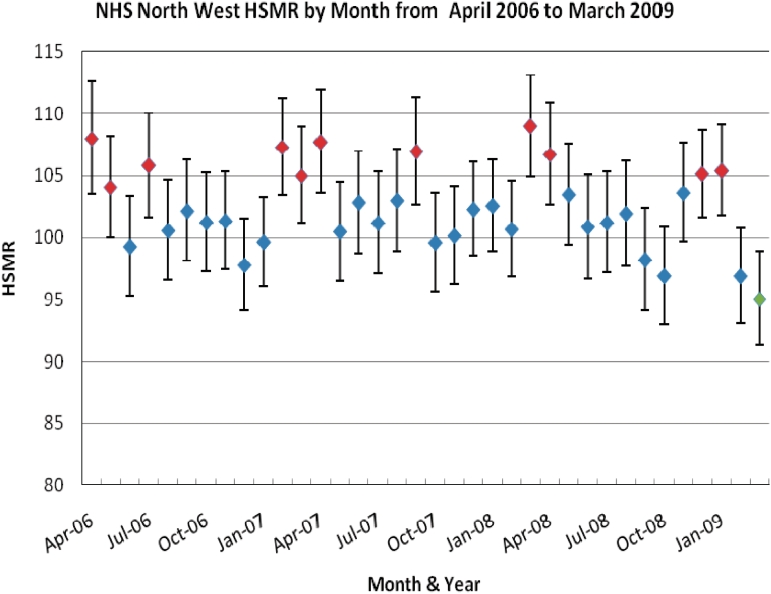

The HSMRs by month for NHS North West and England are included in table form with associated confidence intervals (Tables 1 and 2). When the HSMR analysis for NHS North West is plotted alongside the national trend, a similar pattern for both can be seen throughout the period of analysis.The green markers in Figure 1 show where the HSMR is statistically low in a given month and red markers show where the HSMR is statistically high. When the HSMRs for NHS North West and England are compared against a fixed benchmark year (2005) the data shows a continuing decrease (Figure 2). The NHS North West figures follow the national trend closely at all times.

Table 1.

National HSMR by month

| Financial year | Financial month | Observed | Expected | Relative risk | Low-confidence limit | High-confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1 | 14 033 | 13 481.11 | 104.09 | 102.38 | 105.83 |

| 2006 | 2 | 16 221 | 15 947.86 | 101.71 | 100.15 | 103.29 |

| 2006 | 3 | 15 776 | 16 110.84 | 97.92 | 96.40 | 99.46 |

| 2006 | 4 | 16 106 | 15 296.74 | 105.29 | 103.67 | 106.93 |

| 2006 | 5 | 15 289 | 15 344.27 | 99.64 | 98.07 | 101.23 |

| 2006 | 6 | 14 662 | 15 208.49 | 96.41 | 94.85 | 97.98 |

| 2006 | 7 | 15 763 | 16 023.88 | 98.37 | 96.84 | 99.92 |

| 2006 | 8 | 16 088 | 16 790.16 | 95.82 | 94.34 | 97.31 |

| 2006 | 9 | 17 316 | 18 300.06 | 94.62 | 93.22 | 96.04 |

| 2006 | 10 | 19 042 | 19 619.13 | 97.06 | 95.68 | 98.45 |

| 2006 | 11 | 17 909 | 17 622.42 | 101.63 | 100.14 | 103.13 |

| 2006 | 12 | 17 681 | 18 007.14 | 98.19 | 96.75 | 99.65 |

| 2007 | 1 | 16 271 | 15 629.61 | 104.10 | 102.51 | 105.72 |

| 2007 | 2 | 15 907 | 15 988.03 | 99.49 | 97.95 | 101.05 |

| 2007 | 3 | 14 837 | 15 172.68 | 97.79 | 96.22 | 99.37 |

| 2007 | 4 | 14 749 | 14 863.60 | 99.23 | 97.63 | 100.84 |

| 2007 | 5 | 14 745 | 15 129.35 | 97.46 | 95.89 | 99.05 |

| 2007 | 6 | 14 299 | 14 104.40 | 101.38 | 99.72 | 103.06 |

| 2007 | 7 | 15 511 | 15 980.74 | 97.06 | 95.54 | 98.60 |

| 2007 | 8 | 15 806 | 16 462.00 | 96.02 | 94.52 | 97.52 |

| 2007 | 9 | 17 998 | 18 069.55 | 99.60 | 98.15 | 101.07 |

| 2007 | 10 | 19 239 | 19 501.58 | 98.65 | 97.26 | 100.06 |

| 2007 | 11 | 16 150 | 16 694.96 | 96.74 | 95.25 | 98.24 |

| 2007 | 12 | 16 878 | 16 563.64 | 101.90 | 100.37 | 103.45 |

| 2008 | 1 | 16 754 | 16 220.77 | 103.29 | 101.73 | 104.86 |

| 2008 | 2 | 15 749 | 15 588.59 | 101.03 | 99.46 | 102.62 |

| 2008 | 3 | 14 585 | 14 562.62 | 100.15 | 98.53 | 101.79 |

| 2008 | 4 | 14 690 | 15 177.75 | 96.79 | 95.23 | 98.36 |

| 2008 | 5 | 14 001 | 14 212.50 | 98.51 | 96.89 | 100.16 |

| 2008 | 6 | 14 195 | 14 619.89 | 97.09 | 95.50 | 98.70 |

| 2008 | 7 | 15 728 | 16 236.23 | 96.87 | 95.36 | 98.40 |

| 2008 | 8 | 16 363 | 16 082.91 | 101.74 | 100.19 | 103.31 |

| 2008 | 9 | 21 397 | 20 933.96 | 102.21 | 100.85 | 103.59 |

| 2008 | 10 | 21 362 | 20 843.53 | 102.49 | 101.12 | 103.87 |

| 2008 | 11 | 15 937 | 16 655.38 | 95.69 | 94.21 | 97.18 |

| 2008 | 12 | 16 270 | 17 480.97 | 93.07 | 91.65 | 94.51 |

Table 2.

North West SHA HSMR by month

| Financial year | Financial month | Observed | Expected | Relative risk | Low-confidence limit | High-confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1 | 2174 | 2013.41 | 107.98 | 103.48 | 112.61 |

| 2006 | 2 | 2524 | 2426.19 | 104.03 | 100.01 | 108.17 |

| 2006 | 3 | 2420 | 2437.93 | 99.26 | 95.35 | 103.30 |

| 2006 | 4 | 2447 | 2312.69 | 105.81 | 101.66 | 110.08 |

| 2006 | 5 | 2385 | 2371.77 | 100.56 | 96.56 | 104.68 |

| 2006 | 6 | 2417 | 2366.47 | 102.14 | 98.10 | 106.29 |

| 2006 | 7 | 2462 | 2432.38 | 101.22 | 97.26 | 105.30 |

| 2006 | 8 | 2551 | 2517.56 | 101.33 | 97.43 | 105.34 |

| 2006 | 9 | 2687 | 2748.30 | 97.77 | 94.11 | 101.54 |

| 2006 | 10 | 3011 | 3022.33 | 99.63 | 96.10 | 103.25 |

| 2006 | 11 | 2932 | 2732.56 | 107.30 | 103.45 | 111.25 |

| 2006 | 12 | 2868 | 2731.41 | 105.00 | 101.19 | 108.92 |

| 2007 | 1 | 2566 | 2382.54 | 107.70 | 103.57 | 111.95 |

| 2007 | 2 | 2447 | 2435.41 | 100.48 | 96.53 | 104.54 |

| 2007 | 3 | 2418 | 2351.75 | 102.82 | 98.76 | 107.00 |

| 2007 | 4 | 2357 | 2329.77 | 101.17 | 97.13 | 105.34 |

| 2007 | 5 | 2391 | 2322.09 | 102.97 | 98.88 | 107.18 |

| 2007 | 6 | 2323 | 2172.73 | 106.92 | 102.61 | 111.35 |

| 2007 | 7 | 2459 | 2469.39 | 99.58 | 95.68 | 103.59 |

| 2007 | 8 | 2478 | 2474.66 | 100.14 | 96.23 | 104.16 |

| 2007 | 9 | 2816 | 2753.61 | 102.27 | 98.52 | 106.11 |

| 2007 | 10 | 2952 | 2878.55 | 102.55 | 98.89 | 106.32 |

| 2007 | 11 | 2618 | 2600.77 | 100.66 | 96.84 | 104.59 |

| 2007 | 12 | 2763 | 2535.65 | 108.97 | 104.94 | 113.11 |

| 2008 | 1 | 2616 | 2451.13 | 106.73 | 102.68 | 110.90 |

| 2008 | 2 | 2464 | 2382.25 | 103.43 | 99.39 | 107.60 |

| 2008 | 3 | 2225 | 2206.16 | 100.85 | 96.71 | 105.13 |

| 2008 | 4 | 2373 | 2345.23 | 101.18 | 97.15 | 105.34 |

| 2008 | 5 | 2224 | 2181.87 | 101.93 | 97.74 | 106.26 |

| 2008 | 6 | 2193 | 2233.20 | 98.20 | 94.13 | 102.40 |

| 2008 | 7 | 2375 | 2451.06 | 96.90 | 93.04 | 100.87 |

| 2008 | 8 | 2611 | 2520.76 | 103.58 | 99.64 | 107.63 |

| 2008 | 9 | 3420 | 3253.10 | 105.13 | 101.64 | 108.71 |

| 2008 | 10 | 3257 | 3090.39 | 105.39 | 101.80 | 109.07 |

| 2008 | 11 | 2481 | 2560.75 | 96.89 | 93.11 | 100.77 |

| 2008 | 12 | 2489 | 2618.48 | 95.06 | 91.36 | 98.86 |

Figure 1.

North West SHA HSMR by month from April 2006 to March 2009.

Figure 2.

North West SHA & England HSMR by month from April 2006 to March 2009 with 2005 benchmarks.

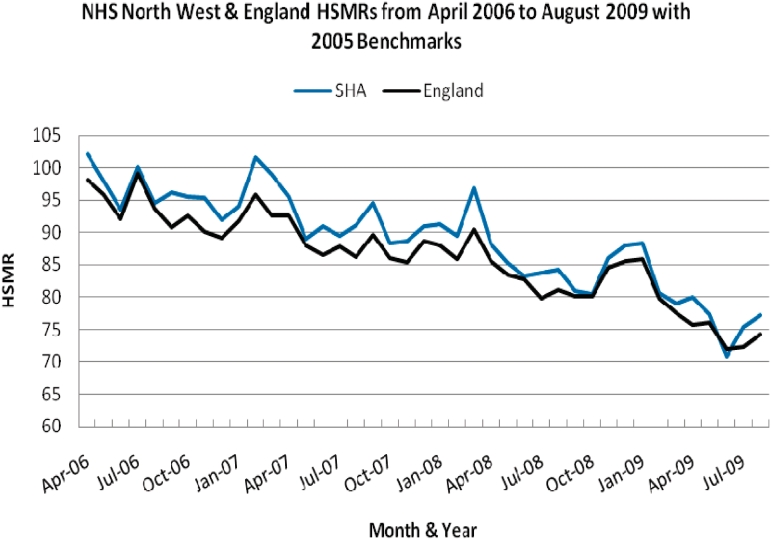

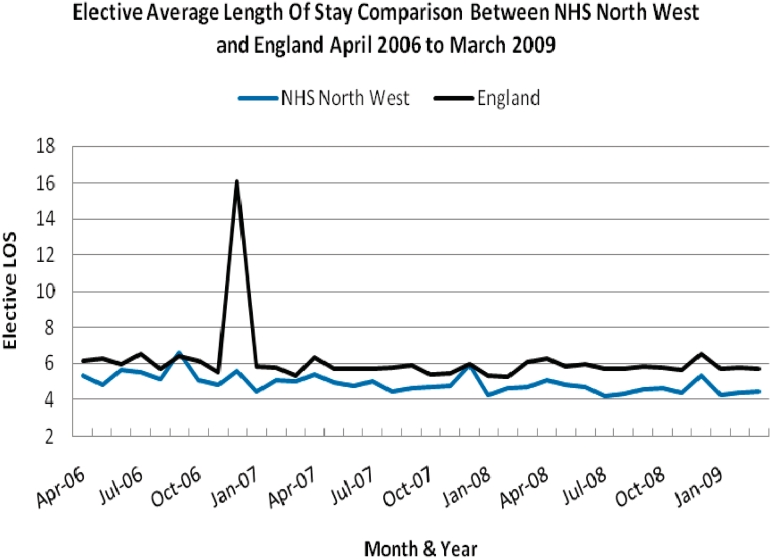

The ALOS by month for NHS North West and England are included in table form with associated confidence intervals (Tables 3 and 4). When the ALOS for elective and non-elective patients across NHS North West is plotted alongside the national trend, once again a similar pattern for both can be seen throughout the period of analysis (Figures 3 and 4).

Table 3.

National ALOS by month

| Financial year | Financial month | Non-elective spells | Non-elective bed days | Non-elective Length of stay | Elective spells | Elective bed days | Elective length of stay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1 | 560 155 | 3 583 923 | 6.39 | 140 734 | 866 833 | 6.16 |

| 2006 | 2 | 592 028 | 3 994 076 | 6.74 | 156 534 | 986 631 | 6.30 |

| 2006 | 3 | 581 955 | 3 786 275 | 6.50 | 160 436 | 952 493 | 5.94 |

| 2006 | 4 | 584 265 | 3 695 384 | 6.32 | 158 024 | 1 035 406 | 6.55 |

| 2006 | 5 | 577 935 | 3 641 041 | 6.29 | 154 641 | 882 057 | 5.70 |

| 2006 | 6 | 579 337 | 3 731 810 | 6.44 | 156 131 | 995 253 | 6.38 |

| 2006 | 7 | 586 801 | 3 646 884 | 6.21 | 159 991 | 983 971 | 6.15 |

| 2006 | 8 | 575 032 | 3 567 735 | 6.20 | 164 885 | 913 653 | 5.54 |

| 2006 | 9 | 581 538 | 3 742 329 | 6.43 | 146 765 | 2 366 563 | 16.13 |

| 2006 | 10 | 592 861 | 3 734 395 | 6.29 | 151 422 | 879 171 | 5.81 |

| 2006 | 11 | 540 871 | 3 433 578 | 6.34 | 150 222 | 867 518 | 5.78 |

| 2006 | 12 | 587 685 | 3 712 307 | 6.31 | 174 312 | 931 691 | 5.35 |

| 2007 | 1 | 553 947 | 3 344 440 | 6.04 | 138 287 | 879 924 | 6.36 |

| 2007 | 2 | 585 376 | 3 476 364 | 5.94 | 155 913 | 891 688 | 5.72 |

| 2007 | 3 | 568 208 | 3 397 584 | 5.98 | 155 662 | 890 068 | 5.72 |

| 2007 | 4 | 580 892 | 3 410 503 | 5.87 | 156 801 | 895 393 | 5.71 |

| 2007 | 5 | 575 585 | 3 335 338 | 5.79 | 151 315 | 876 260 | 5.79 |

| 2007 | 6 | 552 812 | 3 076 003 | 5.56 | 149 001 | 873 906 | 5.87 |

| 2007 | 7 | 589 025 | 3 427 231 | 5.82 | 162 997 | 880 108 | 5.40 |

| 2007 | 8 | 571 285 | 3 341 169 | 5.85 | 163 992 | 894 850 | 5.46 |

| 2007 | 9 | 571 093 | 3 211 611 | 5.62 | 136 217 | 812 565 | 5.97 |

| 2007 | 10 | 582 038 | 3 581 722 | 6.15 | 151 025 | 807 939 | 5.35 |

| 2007 | 11 | 552 351 | 3 329 521 | 6.03 | 162 077 | 850 297 | 5.25 |

| 2007 | 12 | 581 393 | 3 333 778 | 5.73 | 149 936 | 913 187 | 6.09 |

| 2008 | 1 | 584 123 | 3 708 291 | 6.35 | 156 591 | 984 943 | 6.30 |

| 2008 | 2 | 598 458 | 3 393 158 | 5.67 | 152 879 | 887 117 | 5.80 |

| 2008 | 3 | 577 853 | 3 366 717 | 5.83 | 150 938 | 903 224 | 5.99 |

| 2008 | 4 | 605 829 | 3 547 541 | 5.85 | 162 843 | 924 791 | 5.68 |

| 2008 | 5 | 578 418 | 3 181 351 | 5.50 | 143 983 | 824 624 | 5.73 |

| 2008 | 6 | 587 079 | 3 449 686 | 5.88 | 153 500 | 894 024 | 5.82 |

| 2008 | 7 | 613 680 | 3 546 111 | 5.78 | 166 553 | 955 757 | 5.74 |

| 2008 | 8 | 584 686 | 3 337 497 | 5.71 | 154 400 | 873 669 | 5.66 |

| 2008 | 9 | 621 547 | 3 716 861 | 5.98 | 137 479 | 899 885 | 6.55 |

| 2008 | 10 | 595 532 | 3 645 558 | 6.12 | 140 080 | 804 123 | 5.72 |

| 2008 | 11 | 554 104 | 3 323 336 | 6.00 | 141 818 | 815 710 | 5.75 |

| 2008 | 12 | 631 338 | 3 648 723 | 5.78 | 160 270 | 919 499 | 5.73 |

Table 4.

North West SHA ALOS by month

| Financial year | Financial month | Non-elective spells | Non-elective bed days | Non-elective length of stay | Elective spells | Elective bed days | Elective length of stay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1 | 87 774 | 567 622 | 6.47 | 20 685 | 109 669 | 5.30 |

| 2006 | 2 | 92 023 | 585 158 | 6.36 | 23 376 | 112 805 | 4.83 |

| 2006 | 3 | 89 767 | 567 218 | 6.32 | 24 043 | 136 044 | 5.66 |

| 2006 | 4 | 90 521 | 537 883 | 5.94 | 23 041 | 126 581 | 5.49 |

| 2006 | 5 | 89 401 | 544 906 | 6.10 | 22 599 | 116 431 | 5.15 |

| 2006 | 6 | 89 872 | 541 369 | 6.02 | 23 068 | 151 777 | 6.58 |

| 2006 | 7 | 91 568 | 535 539 | 5.85 | 24 012 | 121 517 | 5.06 |

| 2006 | 8 | 90 001 | 556 121 | 6.18 | 25 029 | 120 221 | 4.80 |

| 2006 | 9 | 91 089 | 514 335 | 5.65 | 21 339 | 118 453 | 5.55 |

| 2006 | 10 | 93 352 | 565 595 | 6.06 | 22 850 | 101 881 | 4.46 |

| 2006 | 11 | 83 742 | 527 236 | 6.30 | 22 388 | 113 142 | 5.05 |

| 2006 | 12 | 90 558 | 561 964 | 6.21 | 25 936 | 130 449 | 5.03 |

| 2007 | 1 | 88 458 | 517 785 | 5.85 | 21 545 | 116 515 | 5.41 |

| 2007 | 2 | 93 483 | 540 777 | 5.78 | 24 072 | 118 375 | 4.92 |

| 2007 | 3 | 90 220 | 523 084 | 5.80 | 24 237 | 114 878 | 4.74 |

| 2007 | 4 | 93 827 | 523 928 | 5.58 | 24 202 | 120 877 | 4.99 |

| 2007 | 5 | 92 812 | 504 355 | 5.43 | 23 455 | 104 516 | 4.46 |

| 2007 | 6 | 89 982 | 470 781 | 5.23 | 22 848 | 105 349 | 4.61 |

| 2007 | 7 | 95 081 | 529 860 | 5.57 | 24 741 | 116 265 | 4.70 |

| 2007 | 8 | 91 414 | 513 817 | 5.62 | 25 191 | 119 804 | 4.76 |

| 2007 | 9 | 92 676 | 500 942 | 5.41 | 20 771 | 122 160 | 5.88 |

| 2007 | 10 | 93 002 | 552 966 | 5.95 | 23 191 | 98 263 | 4.24 |

| 2007 | 11 | 89 292 | 514 865 | 5.77 | 24 857 | 114 674 | 4.61 |

| 2007 | 12 | 93 867 | 512 556 | 5.46 | 22 277 | 103 858 | 4.66 |

| 2008 | 1 | 92 079 | 546 410 | 5.93 | 23 245 | 117 387 | 5.05 |

| 2008 | 2 | 94 081 | 523 647 | 5.57 | 22 803 | 110 406 | 4.84 |

| 2008 | 3 | 90 082 | 501 180 | 5.56 | 22 522 | 105 430 | 4.68 |

| 2008 | 4 | 94 073 | 520 434 | 5.53 | 24 350 | 102 210 | 4.20 |

| 2008 | 5 | 90 485 | 489 887 | 5.41 | 21 246 | 91 768 | 4.32 |

| 2008 | 6 | 92 267 | 506 968 | 5.50 | 22 395 | 102 585 | 4.58 |

| 2008 | 7 | 97 068 | 532 857 | 5.49 | 24 364 | 113 150 | 4.64 |

| 2008 | 8 | 93 119 | 514 145 | 5.52 | 22 295 | 97 044 | 4.35 |

| 2008 | 9 | 97 674 | 571 888 | 5.86 | 19 441 | 103 441 | 5.32 |

| 2008 | 10 | 91 928 | 547 480 | 5.96 | 20 606 | 90 610 | 4.27 |

| 2008 | 11 | 87 712 | 490 865 | 5.60 | 21 053 | 92 176 | 4.38 |

| 2008 | 12 | 99 055 | 565 954 | 5.71 | 23 726 | 104 921 | 4.43 |

Figure 3.

North West SHA & England Non-Elective ALOS by month from April 2006 to March 2009.

Figure 4.

North West SHA & England Elective ALOS by month from April 2006 to March 2009.

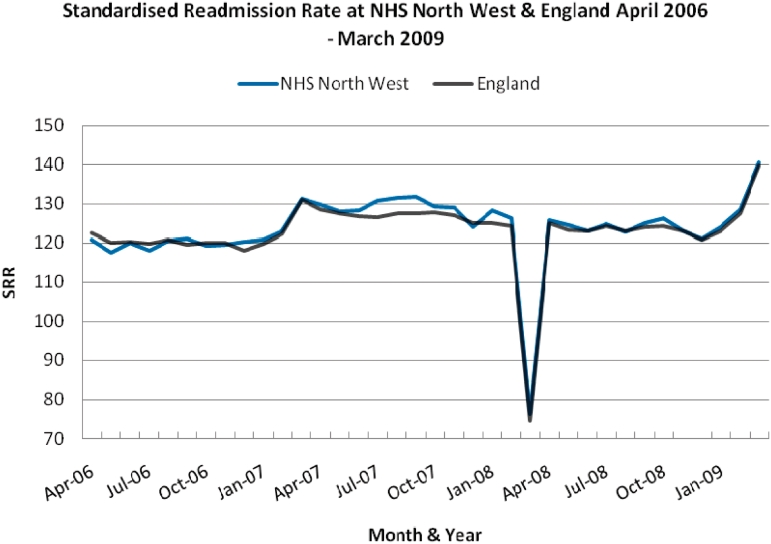

The SRR by month for NHS North West and England are included in table form with associated confidence intervals (Tables 5 and 6). When the SRR for NHS North West is plotted alongside the national trend, once more a similar pattern for both can be seen throughout the period of analysis (Figure 5).

Table 5.

National SRR by month

| Financial year | Financial month | Observed | Expected | Relative risk | Low-confidence limit | High-confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1 | 61 778 | 50 436.30 | 122.49 | 121.52 | 123.46 |

| 2006 | 2 | 69 239 | 57 676.69 | 120.05 | 119.15 | 120.94 |

| 2006 | 3 | 69 512 | 57 772.29 | 120.32 | 119.43 | 121.22 |

| 2006 | 4 | 68 292 | 57 034.15 | 119.74 | 118.84 | 120.64 |

| 2006 | 5 | 69 390 | 57 492.49 | 120.69 | 119.80 | 121.60 |

| 2006 | 6 | 69 258 | 57 925.42 | 119.56 | 118.68 | 120.46 |

| 2006 | 7 | 70 851 | 59 064.74 | 119.95 | 119.07 | 120.84 |

| 2006 | 8 | 70 930 | 59 066.35 | 120.09 | 119.20 | 120.97 |

| 2006 | 9 | 70 354 | 59 568.54 | 118.11 | 117.23 | 118.98 |

| 2006 | 10 | 71 602 | 59 798.56 | 119.74 | 118.86 | 120.62 |

| 2006 | 11 | 66 482 | 54 341.69 | 122.34 | 121.41 | 123.27 |

| 2006 | 12 | 71 075 | 54 246.35 | 131.02 | 130.06 | 131.99 |

| 2007 | 1 | 66 259 | 51 504.84 | 128.65 | 127.67 | 129.63 |

| 2007 | 2 | 71 337 | 55 979.51 | 127.43 | 126.50 | 128.37 |

| 2007 | 3 | 69 016 | 54 409.31 | 126.85 | 125.90 | 127.80 |

| 2007 | 4 | 69 220 | 54 669.00 | 126.62 | 125.68 | 127.56 |

| 2007 | 5 | 69 665 | 54 620.95 | 127.54 | 126.60 | 128.49 |

| 2007 | 6 | 66 477 | 52 145.72 | 127.48 | 126.52 | 128.46 |

| 2007 | 7 | 71 847 | 56 217.44 | 127.80 | 126.87 | 128.74 |

| 2007 | 8 | 70 196 | 55 260.18 | 127.03 | 126.09 | 127.97 |

| 2007 | 9 | 67 946 | 54 289.95 | 125.15 | 124.21 | 126.10 |

| 2007 | 10 | 68 555 | 54 791.32 | 125.12 | 124.19 | 126.06 |

| 2007 | 11 | 65 051 | 52 294.03 | 124.39 | 123.44 | 125.35 |

| 2007 | 12 | 36 592 | 49 068.08 | 74.57 | 73.81 | 75.34 |

| 2008 | 1 | 71 841 | 57 512.20 | 124.91 | 124.00 | 125.83 |

| 2008 | 2 | 73 254 | 59 478.17 | 123.16 | 122.27 | 124.06 |

| 2008 | 3 | 71 054 | 57 757.49 | 123.02 | 122.12 | 123.93 |

| 2008 | 4 | 75 171 | 60 505.15 | 124.24 | 123.35 | 125.13 |

| 2008 | 5 | 70 552 | 57 349.53 | 123.02 | 122.11 | 123.93 |

| 2008 | 6 | 73 810 | 59 520.53 | 124.01 | 123.11 | 124.91 |

| 2008 | 7 | 78 443 | 63 154.74 | 124.21 | 123.34 | 125.08 |

| 2008 | 8 | 73 663 | 59 833.17 | 123.11 | 122.23 | 124.01 |

| 2008 | 9 | 77 125 | 63 916.94 | 120.66 | 119.81 | 121.52 |

| 2008 | 10 | 74 663 | 60 653.37 | 123.10 | 122.22 | 123.98 |

| 2008 | 11 | 71 691 | 56 232.84 | 127.49 | 126.56 | 128.43 |

| 2008 | 12 | 82 032 | 58 641.91 | 139.89 | 138.93 | 140.85 |

Table 6.

North West SHA SRR by month

| Financial year | Financial month | Observed | Expected | Relative risk | Low-confidence limit | High-confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1 | 10 039 | 8306.73 | 120.85 | 118.50 | 123.24 |

| 2006 | 2 | 11 196 | 9525.46 | 117.54 | 115.37 | 119.74 |

| 2006 | 3 | 11 431 | 9523.16 | 120.03 | 117.84 | 122.25 |

| 2006 | 4 | 11 157 | 9444.98 | 118.13 | 115.94 | 120.34 |

| 2006 | 5 | 11 546 | 9571.94 | 120.62 | 118.43 | 122.84 |

| 2006 | 6 | 11 731 | 9690.57 | 121.06 | 118.87 | 123.27 |

| 2006 | 7 | 11 875 | 9963.93 | 119.18 | 117.05 | 121.34 |

| 2006 | 8 | 11 921 | 9963.52 | 119.65 | 117.51 | 121.81 |

| 2006 | 9 | 12 111 | 10076.81 | 120.19 | 118.06 | 122.35 |

| 2006 | 10 | 12 245 | 10141.02 | 120.75 | 118.62 | 122.91 |

| 2006 | 11 | 11 282 | 9167.29 | 123.07 | 120.81 | 125.36 |

| 2006 | 12 | 11 930 | 9090.89 | 131.23 | 128.89 | 133.61 |

| 2007 | 1 | 11 473 | 8833.96 | 129.87 | 127.51 | 132.27 |

| 2007 | 2 | 12 270 | 9577.94 | 128.11 | 125.85 | 130.39 |

| 2007 | 3 | 11 890 | 9267.42 | 128.30 | 126.00 | 130.63 |

| 2007 | 4 | 12 263 | 9370.85 | 130.86 | 128.56 | 133.20 |

| 2007 | 5 | 12 321 | 9375.06 | 131.42 | 129.11 | 133.76 |

| 2007 | 6 | 11 837 | 8980.58 | 131.81 | 129.44 | 134.20 |

| 2007 | 7 | 12 474 | 9643.56 | 129.35 | 127.09 | 131.64 |

| 2007 | 8 | 12 152 | 9425.46 | 128.93 | 126.65 | 131.24 |

| 2007 | 9 | 11 687 | 9417.38 | 124.10 | 121.86 | 126.37 |

| 2007 | 10 | 11 942 | 9308.81 | 128.29 | 126.00 | 130.61 |

| 2007 | 11 | 11 425 | 9049.09 | 126.26 | 123.95 | 128.59 |

| 2007 | 12 | 6465 | 8458.45 | 76.43 | 74.58 | 78.32 |

| 2008 | 1 | 12 193 | 9690.92 | 125.82 | 123.60 | 128.07 |

| 2008 | 2 | 12 430 | 9985.39 | 124.48 | 122.30 | 126.69 |

| 2008 | 3 | 11 878 | 9654.51 | 123.03 | 120.83 | 125.26 |

| 2008 | 4 | 12 437 | 9964.42 | 124.81 | 122.63 | 127.03 |

| 2008 | 5 | 11 755 | 9579.12 | 122.71 | 120.51 | 124.95 |

| 2008 | 6 | 12 411 | 9928.49 | 125.00 | 122.81 | 127.22 |

| 2008 | 7 | 13 321 | 10 550.22 | 126.26 | 124.13 | 128.43 |

| 2008 | 8 | 12 439 | 10 105.70 | 123.09 | 120.94 | 125.27 |

| 2008 | 9 | 12 755 | 10 547.43 | 120.93 | 118.84 | 123.05 |

| 2008 | 10 | 12 317 | 9927.88 | 124.06 | 121.88 | 126.28 |

| 2008 | 11 | 12 112 | 9426.93 | 128.48 | 126.20 | 130.79 |

| 2008 | 12 | 13 654 | 9712.30 | 140.58 | 138.24 | 142.96 |

Figure 5.

North West SHA & England SRR by month from April 2006 to March 2009.

Discussion

For the first time, we present quantitative data which demonstrates that implementation of the EWTD in NHS North West in August 2008 had no adverse impact on key outcomes associated with patient safety and quality of care. HSMR and SRR within the North West continued to improve at a similar rate to the England average after August 2008. The ALOS analysis shows that NHS North West performed better than the national average for the majority of the study period, with no significant change in this pattern in the period following August 2008.

When considering the HSMR trends in detail, three seasonal spikes in the death rate during the December to January period in each financial year analysed can be clearly seen; these occur nationally, and the pattern in NHS North West is no different from the national trend. When the NHS North West HSMR across acute trusts amongst elective and non-elective patients was analysed against 2005 benchmarks across the 3-year period, an overall improvement could be seen which matched the rate of overall HSMR improvement for England, and where the North West showed signs of a decline in improvement this is reflected in the national picture. There was no significant variation from the national HSMR trend immediately following EWTD implementation in the North West, or during the whole period of EWTD implementation from August 2008 until March 2009. Moreover, where NHS North West showed signs of a decline in improvement in the HSMR trend, this is reflected in the national picture demonstrating that this decline in improvement cannot be attributed to a localized issue.

The increase in HSMR in the North West in the winter of 2008/2009 should be examined. There is clear evidence to demonstrate that this increase in HSMR was reflected in the national trend, and this can be attributed to the severe winter pressures related to seasonal infection, exacerbation of chronic disease and hospitalization amongst the growing elderly population.20

Although HSMR figures are clearly a headline statistic when considering the impact of EWTD implementation in NHS North West, data concerning ALOS may provide valuable insights when considering the effectiveness of hospital institutions and clinical teams in satisfactorily and efficiently processing patients. Our data reveal a lower ALOS for both elective and non-elective patients at NHS North West in comparison to England throughout the period studied. Where there is a significant increase in the ALOS for England, this is mirrored at NHS North West. There is an uncharacteristic spike in the elective ALOS at the national level in December 2006 but there is also an increase, although much less significant, at NHS North West in the same month. In the period following August 2008, the ALOS for NHS North West continues to follow the national trend, although it remains lower than the national average. Therefore, it is clear that ALOS has not been impacted in any way that can be attributed to EWTD implementation.

Another useful marker to consider alongside the ALOS when assessing the effective provision of care is the SRR. SRR can provide telling data regarding the effectiveness of initial treatments and highlight those instances in which readmission has been required. When the emergency SRR at NHS North West is compared to that of England for the period April 2006 to March 2009, it can be seen that NHS North West plots a similar pattern to that of the national average. A significant divergence occurs in summer 2007, at which time the SRR in NHS North West rises above the national average. The reason for this is unclear. Similarly, there is a drop in SRR in March 2008 across both England and NHS North West. Again the reason for this is unclear and may be due to a data anomaly, but further investigation of this is beyond the scope of our report. However, it can be stated that the introduction of a 48-h week in NHS North West in August 2008 did not lead to any appreciable trend change in SRR or any significant divergence from the national average.

Much of the credibility of this study rests on the robustness of the HSMR as a measure of patient safety. Since the technique was devised by Jarman et al.21 in the UK in the 1990s, HSMRs have been utilized worldwide to focus the discussion of patient safety and quality improvement, to monitor the provision of care over time and to identify opportunities for improvement. It has become an internationally recognized objective measure of quality of care and, in the author’s opinion it is simply the best tool we currently have with which to quantify and monitor the difficult and multifactorial variables that comprise patent safety and quality of care.14 Indeed, the Canadian Institute for Health Information adopted HSMR analysis as recently as 2005 in order to drive their patent safety and improvement agenda.22 Certainly, the HSMR has its detractors and indeed many researchers do not consider the HSMR to be a suitable measure of, or surrogate marker for, patient safety.23 The pitfalls of HSMR analysis include the possibility for administrative errors such as miscoding and the possibility of missing data. However, missing data or miscoding would be unlikely to account for the clear and consistent trends that we have demonstrated.

The reliability of this article’s claim also depends on the EWTD compliance rate in the North West during the period August 2008 onwards. Robust data exist to demonstrate 94% compliance with a 48-h working week for junior doctors in the North West region of England in August 2008 and this has been published previously.13 Based on a published methodology, EWTD compliance was calculated using New Deal monitoring data.24 In addition, NHS North West did not take the approach of increasing junior doctor numbers and rather directed resources towards sustainable solutions. This did not include any significant targeted increase in the number of junior doctors, rather resources were directed towards ‘Hospital at Night’ schemes, extended practitioner roles and service reconfiguration; this approach was detailed in the article ‘Achieving the 48 h week for Junior Doctors in the North West’.13

Compliance across England did increase in the period leading up to 1 August 2009, as other trusts across England prepared for the EWTD deadline. Individual Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs), as part of their own quality assurance process, began the collection of compliance data in January 2009.25 This information was shared with the Department of Health, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the medical professions. NHS North West’s own data for January 2009 showed that the North West was advancing at a greater pace than the rest of England. The stated EWTD compliance for England in January 2009 was 72%; this increased to 91% by August 2009. It is therefore clear that, during the period of interest (August 2008–August 2009), the North West had a significantly greater degree of compliance with EWTD than the rest of the country, making our comparison truly valid.

Finally, we recognize that the outcome measures in this article (HSMR, SRR and ALOS) are influenced by a multitude of factors other than the working arrangements of junior doctors and we cannot attribute any changes in these parameters to EWTD alone. However, our findings do support the hypothesis that implementation of the EWTD in the North West has had no adverse impact on several key outcomes associated with patient safety.

Conclusions

The implications of these findings are widespread; we can state for the first time that EWTD implementation in the North West region of England has had no obvious adverse effect on parameters of patient safety when considering HSMR, SRR and ALOS across acute trusts among elective and non-elective patients. In fact, there has been continued improvement in these parameters from August 2008, and where trends are at odds with expected results, this is mirrored nationally. No localized variance from national trends could be identified at any stage. The authors do not claim that patient safety improved because of the North West’s efforts to fully implement EWTD in August 2008, but simply wish to demonstrate that these activities did not result in any measurable negative impact on our stated outcome measures.

Patient safety is at the heart of the EWTD, and these results provide a firm basis to support a model which sees well-rested, well-supported doctors deployed efficiently and intelligently within a 48-h week. However, continued efforts will be required to address the challenge posed nationally by the restricted working hours schedule; we must endeavour to sustain excellence in postgraduate medical training and prioritize the continual improvement in quality of patient care within the limits of the WTR’s 48-h week.

Funding

NHS North West Strategic Health Authority.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgements

J.C. and D.K. developed the original idea for the study. J.C. wrote the first draft of the article and wrote subsequent drafts after feedback from the other three authors. All four authors gave final approval. We thank Dr Foster Intelligence for processing the data. We also thank Paul Barbour and James Thompson for their comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Campbell D. The Guardian. [Accessed 11 April 2009]. Doctors’ leader warns 48-hour week will endanger patients. [ http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2009/apr/11/doctor-working-hours] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letter from John Black to Alan Johnson. [Accessed 8 May 2009]. [ http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news/docs/Alan%20Johnson%20EWTD%20Reply.pdf] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pounder R. Junior doctors' working hours: can 56 go into 48? Clin Med. 2008;8:126–7. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.8-2-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Background Briefing; Surgery and the European Working Time Directive. [Accessed 5 March 2009]. The Royal college of Surgeons. [ http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news/new-background-briefing-surgery-and-the-european-working-time-directive] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, Speizer FE, et al. Effect of reducing intern’s work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barger LK, Ayas NT, Cade BE, Cronin JW, Rosner B, et al. Impact of extended-duration shifts on medical errors, adverse events, and attentional failures. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkard S, Tucker P. Shift work safety and productivity. Occup Med. 2003;53:95–101. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horrocks N, Pounder R on behalf of the Multi Multidisciplinary Working Group of the Royal College of Physicians. Designing safer rotas for junior doctors in the 48 hr week. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 2006:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappuccio FP, Bakewell A, Taggart FM, Ward G, Ji C, Sullivan JP, et al. Implementing a 48 h EWTD-compliant rota for junior doctors in the UK does not compromise patients’ safety: assessor-blind pilot comparison. QJM. 2009;102:271–82. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Training Surveys: key findings 2008-2009. [Accessed 14 February 2010]. Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board. P59. [ www.pmetb.org.uk/pmetb] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health, Social Policy and Public Services. New Deal for Junior Doctors. [ http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/scujuniordoc-2] Accessed 14 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dr Wendy Reid, Department of Health. Junior Doctors Across the NHS on Course to Meet New Working Time Target 26th June 2009. [ http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/News/Recentstories/DH_101561] Accessed 14 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendall D, Ahmed-Little Y, Johnston M, Cousins D, Sunderland H, Najim O. EWTD – Achieving the 48 hour week for Junior Doctors in the North West. Br J Healthc Manage. 2009;15:127–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen E, Sandoval C, Zelmer J, Webster G. Understanding and using the hospital standardized mortality ratio in Canada: challenges and opportunities. Healthc Pap. 2008;8:26–36. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2008.19973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Institute for Improvement and Innovation. Quality and Service Improvement Tools-Length of Stay-Reducing Length of Stay. 2008. [ www.institute.nhs.uk/quality and service improvement tools/quality and service improvement tools/length of stay.html] Accessed 14 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hospital Episode Statistics Online. Readmission Rates and HES. [ www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer; jsessionid=3xyd0bm811?siteID=1937&categoryID=927] Accessed 14 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan O, Baker A. Measuring deprivation in England and Wales using 2001 Carstairs scores. Health Stat Q. 2006;31:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneeweiss S, Maclure M. Use of comorbidity scores for control of confounding in studies using administrative databases. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:891–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aylin P, Bottle A, Jen M, Middleton S. Dr Foster Unit-Imperial College, Dr Foster Intelligence. HSMR Mortality Indicators. [ http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/Hospitalmortalityrates/Documents/090424%20MS(H)%20-%20NHS%20Choices%20HSMR%20Publication%20-%20Presentation%20-%20Annex%20C.pdf] Accessed 14 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan RE, Hawker JI, Ayres JG, Adab P, Tunnicliffe W, Olowokure B, et al. Effect of social factors on winter hospital admission for respiratory disease: a case-control study of older people in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:e1–e9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X302682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarman B, Gault S, Alves B, Hider S, Dolan S, Cook A, et al. Explaining differences in English Hospital death rates using routinely collected data. Br Med J. 1999;318:1515–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7197.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Institute for Health Information. HSMR: A New Approach for Measuring Hospital Mortality Trends in Canada. Ottawa: CIHI; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penfold RB, Dean S, Flemons W, Moffatt M. Do hospital standardized mortality ratios measure patient safety? HSMRs in the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. Healthc Pap. 2008;8:8–24. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2008.19972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skills for Health Workforce Projects Team. 2009. [Accessed 14 February 2010]. Doctors Rostering System, DRS Version 3 Rule Book. [ http://www.healthcareworkforce.nhs.uk/working_time_directive/doctors_rostering_system/launch_of_drs_rulebook.html] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SHA. Quality Assurance information. January 2009 (shared with the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges) [Google Scholar]