Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Zileuton is the only 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibitor marketed as a treatment for asthma, and is often utilized as a selective tool to evaluate the role of 5-LOX and leukotrienes. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of zileuton on prostaglandin (PG) production in vitro and in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Peritoneal macrophages activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/interferon γ (LPS/IFNγ), J774 macrophages and human whole blood stimulated with LPS were used as in vitro models and rat carrageenan-induced pleurisy as an in vivo model.

KEY RESULTS

Zileuton suppressed PG biosynthesis by interference with arachidonic acid (AA) release in macrophages. We found that zileuton significantly reduced PGE2 and 6-keto prostaglandin F1α (PGF1α) levels in activated mouse peritoneal macrophages and in J774 macrophages. This effect was not related to 5-LOX inhibition, because it was also observed in macrophages from 5-LOX knockout mice. Notably, zileuton inhibited PGE2 production in LPS-stimulated human whole blood and suppressed PGE2 and 6-keto PGF1α pleural levels in rat carrageenan-induced pleurisy. Interestingly, zileuton failed to inhibit the activity of microsomal PGE2 synthase1 and of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and did not affect COX-2 expression. However, zileuton significantly decreased AA release in macrophages accompanied by inhibition of phospholipase A2 translocation to cellular membranes.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATION

Zileuton inhibited PG production by interfering at the level of AA release. Its mechanism of action, as well as its use as a pharmacological tool, in experimental models of inflammation should be reassessed.

Keywords: cyclooxygenase, leukotrienes, lipopolysaccharide, 5-lipoxygenase, macrophages, phospholipase A2, prostaglandins

Introduction

Zileuton, a benzothiophene N-hydroxyurea, is the only approved inhibitor of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX, EC number 1.13.11.34; nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009) and is thought to intervene with allergic and inflammatory diseases by suppression of leukotriene (LT) biosynthesis (Peters-Golden and Henderson, 2007). The compound belongs to the class of iron ligand-type inhibitors of 5-LOX that not only chelates the active site iron of the enzyme but also possesses weak-reducing properties (Carter et al., 1991). Given the important role that LTs play in airway inflammation, zileuton provides an additional therapeutic option in the management of chronic and persistent asthma. In fact, zileuton was the first and only 5-LOX inhibitor that entered the US market in 1997 as a new type of drug for the prophylaxis and chronic treatment of asthma (Drazen et al., 1999). However, zileuton exhibits liver toxicity, and thus, its clinical use is limited by the need to monitor hepatic enzyme levels. Interestingly, the hepatic injury caused by zileuton appears to be a direct toxic effect that is unrelated to the inhibition of 5-LOX (Beierschmitt et al., 2001).

In addition, zileuton is often utilized as a tool to evaluate the role of 5-LOX and LTs in in vitro as well as in in vivo models of inflammation. In fact, it has shown beneficial effects in a number of pathological conditions in animals, including inflammation of the upper airway, dermatological diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Berger et al., 2007), spinal cord injury (Genovese et al., 2008), colitis (Cuzzocrea et al., 2005), multiple organ injury and dysfunction caused by endotoxemia (Collin et al., 2004), liver metastases (Gregor et al., 2005) and oral carcinogenesis (Li et al., 2005). Generally, the beneficial effects of zileuton in these disorders are attributed to the inhibition of 5-LOX and consequently to a reduced formation of LTs.

It has long been proposed that the inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX, EC number 1.14.99.1) pathway could enhance LT generation by increasing the substrate supply for 5-LOX (Hamad et al., 2004). However, this so-called ‘arachidonate shunt’ hypothesis should be viewed with care because there is some evidence that COX and 5-LOX utilize distinct arachidonate pools (Peters-Golden and Brock, 2000), which would preclude this mechanism. On the contrary, little information is available on prostaglandin (PG) generation when the 5-LOX pathway is inhibited, although in some reports, a concomitant decrease of PG production has been observed in the presence of the 5-LOX inhibitor zileuton (Carter et al., 1991; Chen et al., 2004; Gregor et al., 2005), and more recently, an opposite effect of the compound has been observed in cardiomyocytes (Kwak et al., 2010). Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that genetic [5-LOX gene knockout (KO)] or pharmacological inhibition of 5-LOX by zileuton in murine peritoneal macrophages activated with lipopolysaccharide/interferon γ (LPS/IFNγ) led to a significant decrease in the production of PGs (Rossi et al., 2005). Interestingly, inhibition of PG (i.e. PGE2 and 6-keto PGF1α) production induced by zileuton was greater than that observed as a consequence of 5-LOX-gene deletion. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that other mechanisms than 5-LOX inhibition might contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects of zileuton.

Here, we show that in addition to LT production, zileuton suppressed PG biosynthesis in in vitro models (peritoneal macrophages activated with LPS/IFNγ or zymosan, J774 cells and human whole blood activated with LPS) as well as in rat carrageenan-induced pleurisy. Moreover, our results demonstrated that zileuton inhibited PG production by interfering at the level of arachidonic acid (AA) release.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were in compliance with Italian regulations on protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purpose (Ministerial Decree 116192) as well as with the European Economic Community regulations (Official Journal of E.C. L 358/1 12/18/1986). CD1 mice (25–30 g, Harlan, Milan, Italy), mice with a targeted disruption of the 5-LOX gene (5-LOX KO) (Jackson Laboratories; Harlan, Italy), and Wistar Han rats (200–220 g, Harlan, Milan, Italy) were housed in a controlled environment and provided ad libitum with standard rodent chow and water.

Peritoneal macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages were elicited by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 4% sterile thioglycollate medium (2 mL). After 3 days, mice were killed with carbon dioxide, and macrophages were harvested as described (Nunoshiba et al., 1993). The peritoneal macrophages were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 100 U·mL−1 penicillin, 100 µg·mL−1 streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1.2% sodium pyruvate. Cells were plated in 24-well culture plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells·mL−1 or in 60 mm-diameter culture dishes (3 × 106 cells3·mL−1 dish) and allowed to adhere at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 h, and then non-adherent cells were removed by washing with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Immediately before the experiments, the culture medium was replaced by fresh medium without FBS in order to avoid interference with the radioimmunoassay (RIA).

The peritoneal macrophages were treated with Escherichia coli LPS (Serotype 0111:B4, 10 µg·mL−1) plus IFNγ (100 U·mL−1) for 24 h or zymosan (20–30 particles·cell−1) for 60 min. Incubation media were assayed for prostanoids (PGE2 and 6-keto PGF1α) and cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLTs) by RIA and enzyme immunoassay (EIA), respectively. The levels of eicosanoids are expressed as ng·mL−1. Cells were used for Western blot analysis.

Mitochondrial respiration

Cell respiration was assessed by the mitochondria-dependent reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) to formazan (Mosmann, 1983). After stimulation with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) and IFNγ (100 U·mL−1) in the absence or presence of zileuton (1–10–100 µM) for 24 h, cells were incubated with MTT (0.2 mg·mL−1) in 96-well plates for 1 h. Culture medium was removed by aspiration and the cells were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0.1 mL). The extent of cellular reduction of MTT to formazan was quantified by the measurement of optical density (OD) at 550 nm.

J774 macrophages

The murine monocyte/macrophage J774 cell line was grown in DMEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 100 U·mL−1 penicillin, 100 µg·mL−1 streptomycin, 10% FBS and 1.2% sodium pyruvate. Cells were plated in 24-well culture plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells·mL−1 or in 60 mm-diameter culture dishes (3 × 106 cells per 3 mL dish) and allowed to adhere at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. Immediately before the experiments, culture medium was replaced by fresh medium without FBS and cells were stimulated as described.

Activation of COX-2 in J774 macrophages

Cells were stimulated with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) for 24 h (Sautebin et al., 1999) in the absence or presence of zileuton (1 to 100 µM). In other experiments, after cell stimulation (LPS 10 µg·mL−1 for 24 h), the supernatant was replaced with fresh medium containing vehicle or zileuton (100 µM) and incubated for 15 min before the addition of AA (3–15 µM) for 30 min. The measurement of PGE2 and 6-keto PGF1α in the cell supernatants was performed by RIA, whereas the cells were used for Western blot studies.

Human whole blood assay

Peripheral blood from healthy adult volunteers, who had not received any medication for at least 2 weeks under informed consent, was obtained by venepuncture and collected in syringes containing heparin (10 U·mL−1). To evaluate PG production in whole blood, 1 mL aliquots of human blood samples were incubated, in the presence or absence of zileuton (1, 3.3, 10, 33 and 100 µM) with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) or saline (control) for 24 h at 37°C as previously described (Tacconelli et al., 2002). PGE2 plasma levels were measured by RIA.

Carrageenan-induced pleurisy in rats

Zileuton (10 mg·kg−1), MK-886 (1.5 mg·kg−1) or indomethacin (5 mg·kg−1) were given i.p. 30 min before carrageenan. A group of rats received the vehicle (DMSO, 4%, i.p.) 30 min before carrageenan. Rats were anaesthetized with enflurane 4% mixed with O2, 0.5 L·min−1, N2O 0.5 L·min−1 and submitted to a skin incision at the level of the left sixth intercostal space. The underlying muscle was dissected, and saline (0.2 mL) or λ-carrageenan type IV 1% (w·v−1) (0.2 mL) was injected into the pleural cavity. The skin incision was closed with a suture, and the animals were allowed to recover. At 4 h after the injection of carrageenan, the animals were killed by inhalation of CO2. The chest was carefully opened, and the pleural cavity was rinsed with 2 mL saline solution containing heparin (5 U·mL−1). The exudate and washing solution were removed by aspiration, and the total volume was measured. Any exudate that was contaminated with blood was discarded. The amount of exudate was calculated by subtracting the volume injected (2 mL) from the total volume recovered. Leukocytes in the exudate were resuspended in PBS and counted with a light microscope in a Burker's chamber after vital trypan blue staining.

The amounts of PGE2, 6-keto PGF1α and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) in the supernatant of centrifuged exudate (800×g for 10 min) were assayed by RIA (PGE2) and EIA (6-keto PGF1α and LTB4) according to the manufacturer's protocol, respectively. The results are expressed as ng per rat and represent the mean ± standard error (SE) of 14 rats.

Determination of PGE2 synthase activity in A549 microsomes

Preparation of microsomes of A549 cells and determination of microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase (mPGES1) activity was performed as described (Jakobsson et al., 1999; Thorén and Jakobsson, 2000). In brief, cells (2 × 106 cells in 20 mL medium) were plated in 175 cm2 flasks and incubated for 16 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, the cell culture medium was exchanged against DMEM high glucose (4.5 g·L−1) medium containing 2% fetal calf serum. In order to induce expression of mPGES1, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (1 ng·mL−1) was added and cells were incubated for another 72 h. Thereafter, cells were detached with trypsin/EDTA, washed with PBS and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ice-cold homogenization buffer [0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 60 µg·mL−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 µg·mL−1 leupeptin, 2.5 mM glutathione (GSH) and 250 mM sucrose] was added, and after 15 min at room temperature, cells were resuspended and sonicated on ice (3 × 20 s). The homogenate was subjected to differential centrifugation at 10 000×g for 10 min and 174 000×g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet (microsomal fraction) was resuspended in 1 mL homogenization buffer and total protein concentration was determined by the Coomassie protein assay (Bradford, 1976). Microsomal membranes were diluted in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing 2.5 mM GSH. The reaction (100 µL total volume) was initiated by addition of PGH2 (20 µM, final concentration). After 1 min at 4°C, the reaction was terminated with 100 µL of stop solution (40 mM FeCl2, 80 mM citric acid and 10 µM of 11β-PGE2). PGE2 was separated by solid phase extraction using acetonitrile (200 µL) and analysed by RP-HPLC [30% acetonitrile aq. + 0.007% trifluoroacetic acid (v·v−1), Nova-Pak® C18 column, 5 × 100 mm, 4 µm particle size, flow rate 1 mL·min−1] with ultraviolet (UV) detection at 195 nm. 11β-PGE2 was used as internal standard to quantify PGE2 product formation by integration of the area under the peaks.

Activity assay of isolated COX-2

The effect of zileuton on the activity of isolated human COX-2 was investigated as described (Siemoneit et al., 2008). Briefly, purified COX-2 (human recombinant, 20 units; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was diluted in 1 mL reaction mixture containing 100 mM Tris buffer pH 8, 5 mM GSH, 5 mM haemoglobin and 100 mM EDTA at 4°C, and pre-incubated with the test compounds for 5 min. Samples were pre-warmed for 60 s at 37°C and AA (2 µM) was added to start the reaction. After 5 min at 37°C, 12(S)-hydroxy-5-cis-8,10-trans-heptadecatrienoic acid was extracted and then analysed by HPLC [76% MeOH aq + 0.007% trifluoroacetic acid (v·v−1), Nova-Pak® C18 column, 5 × 100 mm, 4 µm particle size, flow rate 1 mL·min−1] with UV detection at 235 nm.

[3H]-AA labelling

J774 cells or elicited peritoneal macrophages were labelled with 0.5 µCi·mL−1 and 0.1 µCi·mL−1[5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H(N)]AA (180–240 Ci·mmol−1), respectively, overnight at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% FBS. After labelling, the cells were washed three times with PBS containing 2 mg·mL−1 fatty acid-free BSA. Thereafter, J774 macrophages were stimulated for 24 h with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) and peritoneal macrophages for 60 min with Ca2+-ionophore A23187 (1 µM) or zymosan (20–30 particles·cell−1) in the absence or presence of zileuton (1–10–100 µM) (Gijón et al., 2000). After incubation, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged for 10 min at 10 000×g, and the cells were scraped into 0.5 mL of 0.1% triton X-100. The amount of radioactivity in the cells and in the culture media was measured by liquid scintillation counting (Tri-Carb 1500, Packard, Milan, Italy). Background release from unstimulated cells was subtracted from each experimental point.

Determination of cell-free activity of human recombinant cytosolic phospholipase A2

The cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) coding sequence was cloned from pVL1393 plasmid (kindly provided by Dr Wonhwa Cho, University of Illinois at Chicago) into pFastBac™ HT A containing a 6× His-tag coding sequence. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into DH10Bac™E. coli. Sf9 cells were transfected with recombinant bacmid DNA using Cellfectin® Reagent and the generated baculovirus was amplified. Overexpression of His-tagged cPLA2 in baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells and isolation using Ni-NTA agarose beads was performed as described (de Carvalho et al., 1993). Multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) were prepared by drying 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol in a ratio of 2:1 (n·n−1, in chloroform) under nitrogen. MLVs were downsized to large unilamellar vesicles by extrusion (100 nm pore diameter). Final total concentration of lipids was 250 µM in 200 µL. Test compounds and 1 mM Ca2+ were added to the vesicles, and the reaction was started by addition of 500 ng His-tagged cPLA2 (in 10 µL buffer). After 1 h at 37°C, 1.6 mL MeOH was added, and AA was extracted by RP-18 solid phase extraction. Following derivatization with p-anisidium chloride, the resulting mixture was analysed by RP-HPLC at 249 nm, as described by Knospe et al. (1988).

Western blot analysis

The analysis of COX-2, β-actin and cPLA2 was performed in whole cell lysates. The cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed for 10 min at 4°C with lysis buffer [50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)] containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Lysates from adherent cells were collected by scraping and centrifuged at 12 000×g for 15 min at 4°C.

For analysis of cPLA2 subcellular localization, J774 cells or peritoneal macrophages were resuspended in 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 60 µg·mL−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor and 10 µg·mL−1 leupeptin, 6 h after LPS treatment (J774 cells) or 60 min after zymosan treatment (peritoneal macrophages) sonicated on ice (5 × 10 s), and centrifuged at 100 000×g 100 min−1 4°C. The 100 000×g supernatant was referred to soluble fraction (S100); the corresponding pellet was referred to membrane fraction (P100).

Protein concentration in cell lysates was determined by Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Muenchen, Germany). Equal amounts of protein (25–35 µg corresponding to 2–4 × 105 cells) were mixed with gel loading buffer (50 mM Tris, 10% SDS, 10% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mg·mL−1 of bromophenol blue) in a ratio of 1:1, boiled for 3 min and centrifuged at 10 000×g for 10 min. Each sample was loaded and analysed by electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL Nitrocellulose, Amersham, Rainham, UK). Correct loading of the gel and transfer of proteins to the nitrocellulose membrane was confirmed by Ponceau S staining. The membranes were blocked with 0.05% PBS-Tween containing 3% non-fat dry milk for COX-2; with 0.1% PBS-Tween containing 5% non-fat dry milk for β-actin and cPLA2. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Rabbit monoclonal anti-COX-2 antibody (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, USA) was diluted 1:8000 in 0.05% PBS-Tween, 3% non-fat dry milk; mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was diluted 1:20 000 in 0.1% PBS-Tween, 5% non-fat dry milk; rabbit polyclonal anti-cPLA2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was diluted 1:500 in 0.1% PBS-Tween. After incubation, the membranes were washed six times with 0.1% PBS-Tween and incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1:3000 in 0.1% PBS-Tween containing 5% non-fat dry milk. The membranes were washed and protein bands were detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM) of the mean of n observations, where n represents the number of experiments performed in different days or the number of animals. Triplicate wells were used for the various treatment conditions. The IC50 values were calculated by GraphPad Instat program; data fit was obtained using the sigmoidal dose–response equation (variable slope) (GraphPad software) (eicosanoid background release from unstimulated cells was subtracted from each experimental point).

The results were analysed by one-way anova followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials

AA (peroxide free) and MK-886 were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Inalco, Milan, Italy). The 6-keto PGF1α antibody was a gift from Prof G. Ciabattoni (University of Chieti, Italy). [3H-PGE2], [3H-6-keto PGF1α] and [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H(N)]AA were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Milan, Italy). Zileuton was purchased from Sequoia Research Products (Oxford, UK). EIA kit was from Cayman Chemical Company. Indomethacin and λ-carrageenan type IV isolated from Gigartina aciculaire and Gigartina pistillata were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). All other reagents and compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Stock solutions of zileuton were prepared in ethanol or in DMSO (for human whole blood assay); an equivalent amount of ethanol or DMSO was included in control samples. For animal studies, zileuton, MK-886 and indomethacin were dissolved in DMSO and diluted with saline achieving a final DMSO concentration of 4%. Prior to use as a stimulus, zymosan was suspended in PBS and boiled for 10 min, followed by centrifugation. After resuspension in PBS, the boiling procedure was repeated twice more (Gijón et al., 2000).

Results

Effects of zileuton on PGE2 production in elicited murine peritoneal and in J774 macrophages

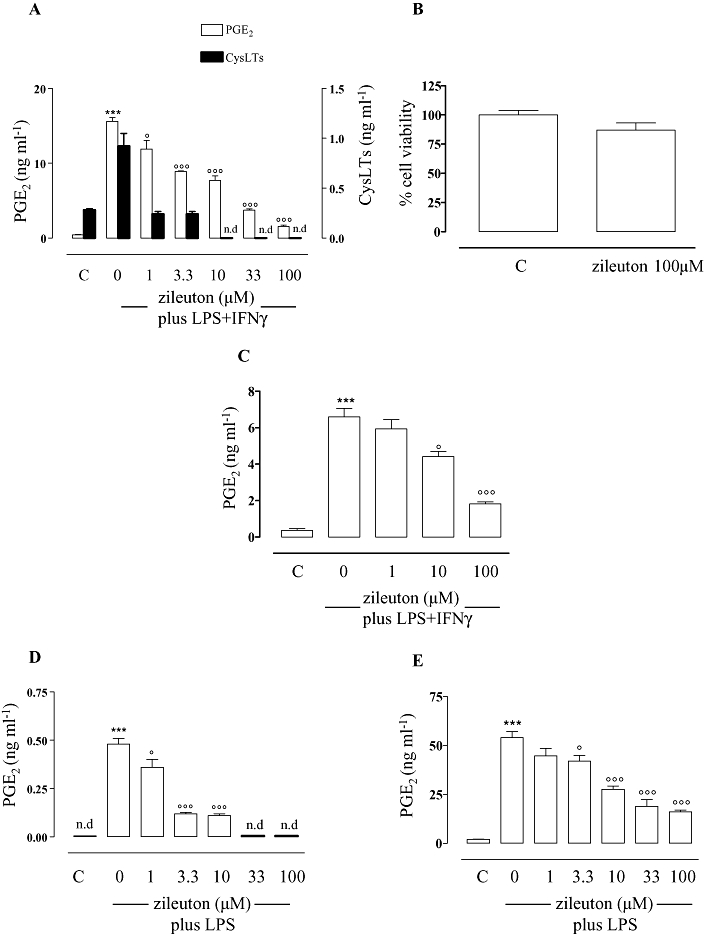

Stimulation of elicited murine peritoneal macrophages with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) plus IFNγ (100 U·mL−1) for 24 h induced a significant (P < 0.001) increase of PGE2 generation (about 37-fold) compared with unstimulated cells (control). In the presence of increasing concentrations of zileuton (1–100 µM), a significant and concentration-dependent inhibition (P < 0.05 at 1 µM; P < 0.001 at all the other concentrations tested) of PGE2 production was observed (Figure 1A). The calculated IC50 was 5.79 µM (r2 = 0.968). In accordance with its reported efficacy in various cell-based assays [IC50 = 0.5 to 1 µM] (Carter et al., 1991), zileuton completely inhibited the elicited formation of cys-LTs at all the concentrations tested (Figure 1A). The inhibition of PGE2 and cys-LTs was not related to a toxic effect of the compound, as evaluated by assessment of cell viability (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Effects of zileuton on prostaglandin production in macrophages and in human whole blood. Zileuton inhibits eicosanoid production in peritoneal macrophages from 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) wild type (WT) (A) and from 5-LOX KO mice (C) activated for 24 h with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 µg·mL−1) and interferon γ (IFNγ) (100 U·mL−1) as well as in J774 macrophages (D) and in human whole blood (E) stimulated, for 24 h, with LPS (10 µg·mL−1). Eicosanoid levels were quantified by radioimmunoassay (PGE2) and enzyme immunoassay [cysteinyl leukotriene (cysLT)] in medium from cell incubations. Zileuton did not inhibit cell viability in peritoneal macrophages from 5-LOX WT as determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide cell viability assay (B). Data are expressed as means ± SEM from n = 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate, each. n.d. = not detectable (the level of the eicosanoids was below the detection limit of the respective assay). ***P < 0.001 versus unstimulated cells (C), °P < 0.05; °°°P < 0.001 versus cells activated with LPS + IFNγ (peritoneal macrophages) or LPS (J774 macrophages and human whole blood) in the absence of zileuton.

To determine whether the suppression of PG production was related to the inhibition of LTs, we evaluated the effect of zileuton on PGE2 biosynthesis in activated peritoneal macrophages from 5-LOX KO mice. These cells do not produce any detectable amount of LTs. However, as observed with cells from 5-LOX wild type (WT) mice, zileuton inhibited PGE2 formation in a concentration-dependent manner also in activated peritoneal macrophages from 5-LOX KO mice, although with a slightly higher IC50 (21.1 µM, r2 = 0.998; Figure 1C). These data indicate a direct inhibitory effect of zileuton on PG biosynthesis.

Similar inhibitory effects of zileuton on PGE2 production were observed in the murine macrophage cell line J774. Stimulation of J774 macrophages with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) for 24 h to induce COX-2 expression produced a significant (P < 0.001) increase of PGE2 compared to unstimulated cells (control) (Figure 1D). As observed in mouse peritoneal macrophages, zileuton (1–100 µM) significantly (P < 0.05 at 1 µM; P < 0.001 at all the other concentrations tested) inhibited PGE2 production in a concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 1.94 µM (r2 = 0.934; Figure 1D).

Effects of zileuton on PGE2 production in human whole blood and on carrageenan-induced pleurisy

Next, we evaluated whether zileuton also affected PG production in a more biologically relevant system, such as human whole blood stimulated with LPS (10 µg·mL−1), and in vivo, in a model of acute inflammation in rats. Importantly, zileuton (1–100 µM) significantly (P > 0.05 at 1 µM; P < 0.05 at 3.3 µM; P < 0.001 at all the other concentrations tested) and concentration-dependently inhibited COX-2-dependent PGE2 production in human whole blood, with an IC50 of 12.9 µM (r2 = 0.965; Figure 1E).

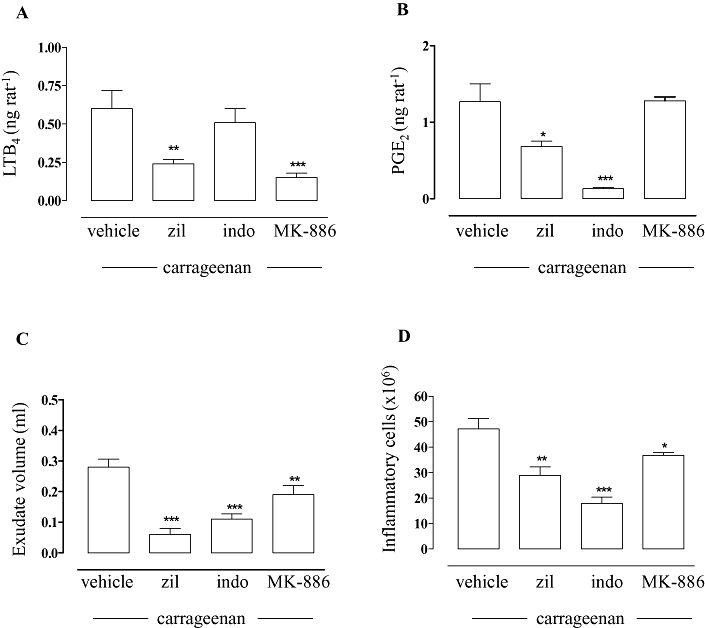

In an in vivo model of carrageenan-induced rat pleurisy, zileuton (at the dose of 10 mg·kg−1, i.p.) significantly reduced not only the pleural exudate levels of LTB4 (60%, P < 0.01) (Figure 2A) but also of PGE2 (47%, P < 0.05) (Figure 2B) as well as the inflammatory reaction measured as exudate volume (79%, P < 0.001) (Figure 2C) and number of migrating cells (39%, P < 0.01) (Figure 2D). A reduced PG production, exudate volume and number of inflammatory cells were also observed for the COX inhibitor indomethacin (5 mg·kg−1, i.p.) which failed to significantly suppress LTB4 levels (Figure 2A–D). Moreover, the PGE2 reduction was not dependent on the LT inhibition, since MK-886 (1.5 mg·kg−1, i.p.), which also reduced LTB4 production (75%, P < 0.001), failed to decrease PGE2 levels (Figure 2A,B). Note that the effect of zileuton in reducing exudate formation and inflammatory cell migration was greater than that of MK-886, although MK-886 led to a greater reduction of LTB4 levels than zileuton, suggesting that zileuton's effects were not simply related to inhibition of LTB4 formation.

Figure 2.

Effects of zileuton on prostaglandin production in pleural exudates from carrageenan-treated rats. Thirty minutes before intrapleural injection of carrageenan, rats [n = 7 for each experimental group for each experiment (n = 2)] were treated i.p. with 10 mg·kg−1 zileuton (zil), 1.5 mg·kg−1 MK-886, 5 mg·kg−1 indomethacin (indo) or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide, 4%). Zileuton inhibited LTB4 (A) and PGE2 pleural levels (B), as well as exudate volume (C) and inflammatory cell accumulation in the pleural cavity (D) 4 h after carrageenan injection. Eicosanoid levels were quantified by radioimmunoassay (PGE2) and enzyme immunoassay (LTB4). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle.

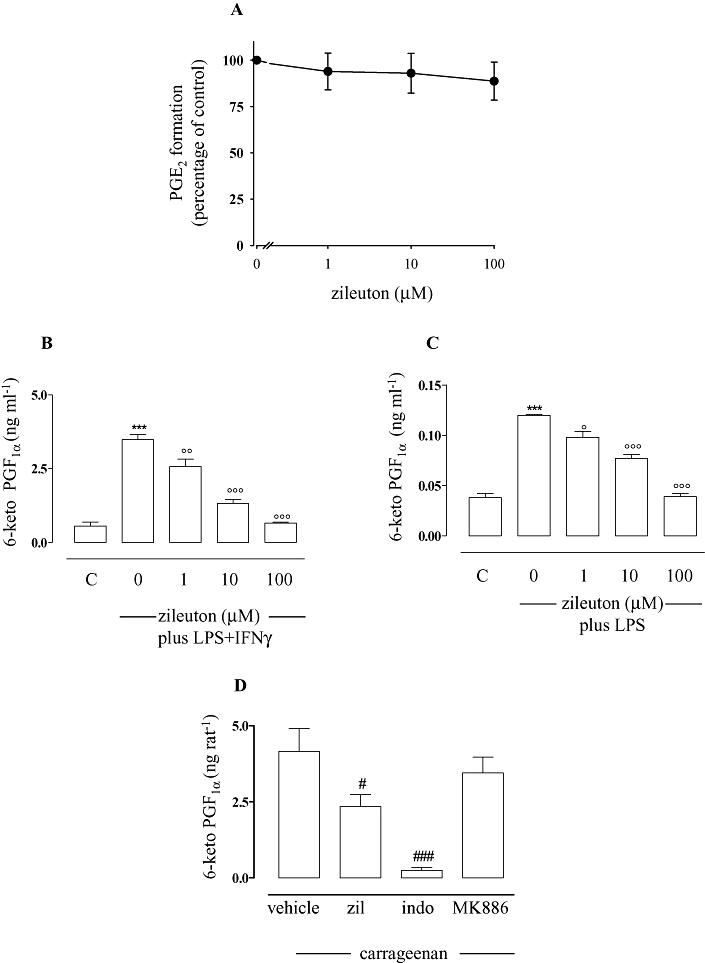

Effect of zileuton on mPGES1 and COX-2

The next step was to identify at which level zileuton inhibited PGE2 production. One possibility to be considered was that zileuton could inhibit PGE2 formation by interference with mPGES1, which represents the downstream enzyme involved in PGE2 synthesis, in particular under inflammatory conditions. To this aim, zileuton was tested in a cell-free assay system using isolated microsomes from IL-1β-treated A549 cells as the enzyme source (Jakobsson et al., 1999; Thorén and Jakobsson, 2000). Zileuton (1–100 µM) did not inhibit mPGES1 activity (conversion of PGH2 to PGE2) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of zileuton on microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase (mPGES1) activity and 6-keto PGF1α production. Zileuton did not significantly inhibit mPGES1 activity (A). Enzyme activity was determined as described. Zileuton inhibited 6-keto PGF1α production in peritoneal macrophages activated, for 24 h, with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 µg·mL−1) and interferon γ (IFNγ) (100 U·mL−1) (B), as well as in J774 macrophages stimulated, for 24 h, with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) (C), and in carrageenan-induced pleural exudates (D). Prostanoid levels were quantified by radioimmunoassay in medium from cell incubations and enzyme immunoassay in pleural exudates. Data are expressed as means ± SEM from n = 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate, each. ***P < 0.001 versus unstimulated cells (C), °P < 0.05; °°P < 0.01; °°°P < 0.001 versus cells activated in the absence of zileuton with LPS + IFNγ (peritoneal macrophages) or LPS (J774 macrophages); #P < 0.05; ###P < 0.001 versus in the presence of vehicle (carrageenan-induced pleurisy).

Moreover, zileuton inhibited the generation of other COX-derived product such as the stable PGI2 metabolite, 6-keto PGF1α. Thus, as for PGE2 production, in the presence of increasing concentrations of zileuton (1–10–100 µM), a significant concentration-dependent inhibition of stimulated 6-keto PGF1α generation was observed in murine peritoneal macrophages (IC50 = 2.7 µM; r2 = 0.998) (Figure 3B). Similar results were obtained in J774 cells (Figure 3C; IC50 = 5.8 µM; r2 = 0.928). A significant reduction of 6-keto PGF1α levels by zileuton (10 mg·kg−1) was also observed in vivo in carrageenan-induced pleurisy (Figure 3D). These data suggested that zileuton might influence an upstream event in PG biosynthesis.

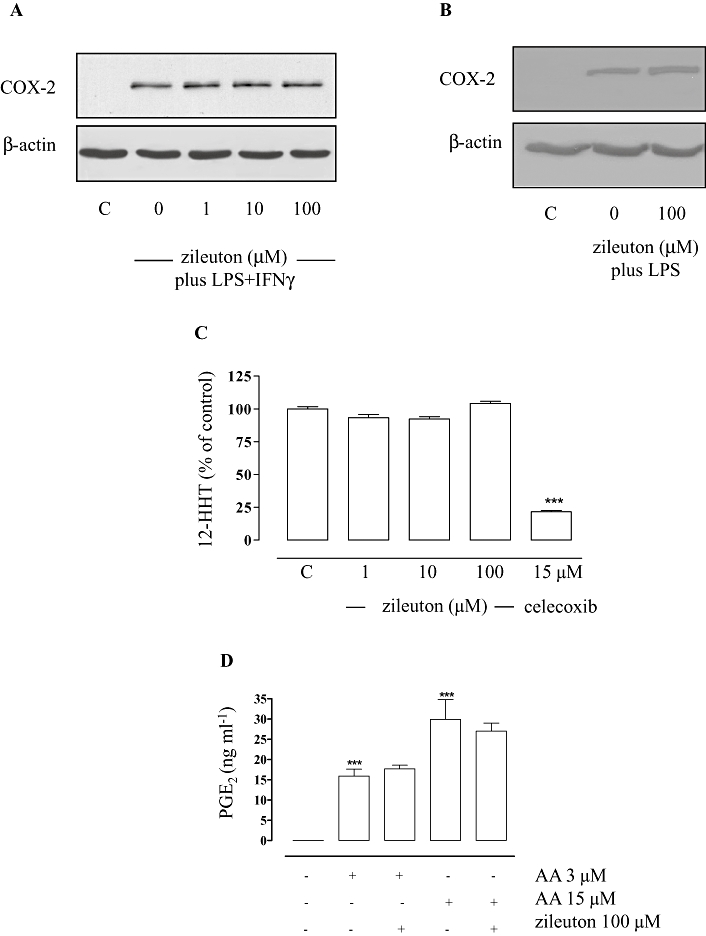

In activated macrophages, COX-2 is the enzyme responsible for PG production from AA (Brock et al., 1999; Rossi et al., 2005). However, although our data point to an interference of zileuton with COX enzymes, the expression of COX-2 was neither significantly inhibited by zileuton (1–100 µM) in mouse peritoneal macrophages activated with LPS (10 µg·mL−1)/IFNγ (100 U·mL−1) (Figure 4A) nor in J774 cells activated with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) for 24 h (Figure 4B). Also, zileuton (1–10–100 µM) did not inhibit the activity of isolated human COX-2 enzyme (Figure 4C). Importantly, after stimulation of J774 cells with LPS (10 µg·mL−1) for 24 h (to induce COX-2), followed by a washout step and 30 min incubation with exogenous AA (3 and 15 µM, Figure 4D), PGE2 generation was unaffected by zileuton. Together, these results exclude mPGES1 or COX-2 expression and enzymatic activities as possible target of zileuton. Instead, data showing that zileuton failed to inhibit PGE2 formation when exogenous AA was added pointed to a possible action of zileuton at the level of AA supply.

Figure 4.

Effects of zileuton on cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 activity and expression. Zileuton did not significantly inhibit COX-2 expression in peritoneal macrophages (A) and J774 macrophages (B) activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 µg·mL−1)/ interferon γ (IFNγ) (100 U·mL−1) and LPS (10 µg·mL−1) for 24 h, respectively, as well as enzymatic activity of isolated COX-2 (C). Enzyme activity assays of isolated COX-2, cell lysates and Western blot analysis were performed as described. After J774 stimulation (LPS 10 µg·mL−1 for 24 h), the supernatant was replaced with fresh medium containing vehicle or zileuton and pre-incubated for 15 min and incubated for another 30 min in the presence of arachidonic acid (AA) (3–15 µM) (D). The illustrated blots are representative of at least 3 separate experiments. PGE2 levels were measured by RIA. Data are expressed as means ± SEM from four separate experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001 versus control.

Effect of zileuton on cPLA2 and AA release

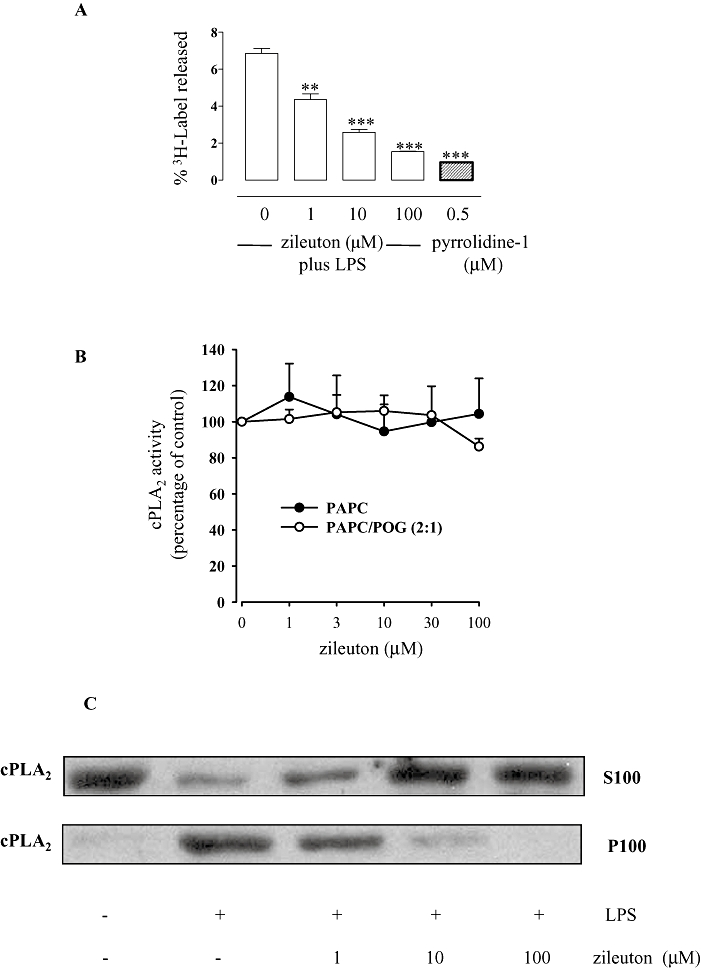

Next, we evaluated the effect of zileuton on the proximal step of eicosanoid biosynthesis, the release of AA, which is mediated in macrophages by cPLA2 (Gijón et al., 2000). For this, release of [3H]-AA and its metabolites from [3H]-AA-labelled J774 macrophages stimulated by LPS (10 µg·mL−1) for 24 h was assessed. Zileuton (1–100 µM) significantly (P < 0.01 at 1 µM; P < 0.001 at 10 and 100 µM) inhibited the release of radioactivity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5A) with an IC50 of 3.5 µM (r2 = 0.994). Pyrrolidine-1, a well-recognized inhibitor of cPLA2 (Seno et al., 2000), was used as reference compound. On the other hand, zileuton (up to 100 µM) neither affected the enzymatic activity of purified human recombinant cPLA2 in a cell-free assay (regardless of the nature of the phospholipid substrate, Figure 5B) nor the expression (LPS-stimulated macrophages) of cPLA2 (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effects of zileuton on the release of radioactivity from [3H]-AA-labelled J774 macrophages, cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) activity and translocation. Zileuton significantly inhibited the release of [3H]-AA and its metabolites from [3H]-AA-labelled J774 macrophages activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 µg·mL−1) (A). Background release from unstimulated cells was about 2%. Radioactivity release was determined and expressed as percentage of the total radioactivity (cell-associated plus media). Data are expressed as means ± SEM from three separate experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus cells activated with LPS in absence of zileuton. Zileuton did not inhibit the activity of isolated human cPLA2 (B). The release of arachidonic acid (AA) from 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PAPC) or from PAPC/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol (POG) (2:1) was determined as described in the Methods. Data (means ± SEM) are expressed as percentage of control (no zileuton, 100%). Pyrrolidine-1 (0.5 µM, used as control) suppressed cPLA2 activity by about 95% (not shown). Zileuton inhibited cPLA2 translocation (C) in J774 macrophages activated with LPS (10 µg·mL−1). Cell lysates and Western blot analysis were performed as described. The illustrated blots are representative of at least three separate experiments.

In intact leukocytes, AA release requires translocation of cPLA2 from the cytosol (S100) to the cellular membranes (P100) (Gijón et al., 1999). We found that zileuton (10 and 100 µM) almost completely blocked the translocation of cPLA2 to the membrane compartment following LPS stimulation of J744 macrophages (Figure 5C).

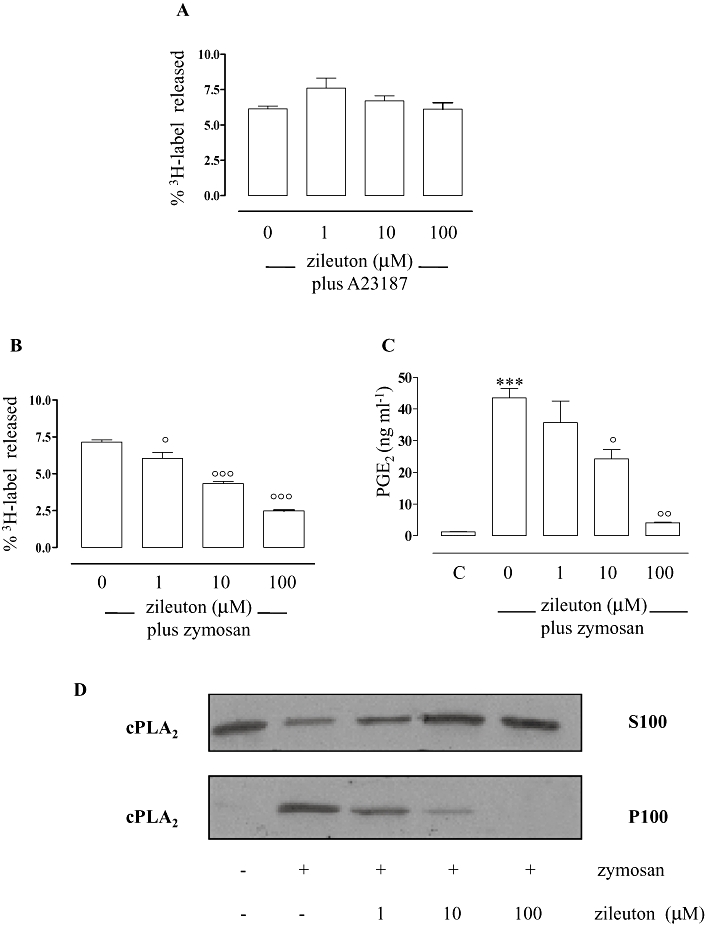

In macrophages, cPLA2 is stimulated to release AA by a wide variety of agents other than LPS, such as the unphysiological Ca2+-ionophore A23187 and the physiologically relevant stimulus zymosan (Gijón et al., 2000). Thus, we evaluated the effect of zileuton on the AA release in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with calcium ionophore A23187 or zymosan. Zileuton (1–100 µM) failed to inhibit radioactivity release (Figure 6A) in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with A23187 (1 µM), whereas it was effective (P < 0.05 at 1 µM; P < 0.001 at 10 and 100 µM) when the cells were stimulated with zymosan (30 particles·cell−1) (Figure 6B; IC50 = 8.13 µM; r2 = 0.997). In parallel, we observed a concentration-dependent inhibition (P > 0.05 at 1 µM; P < 0.05 at 10 µM; P < 0.01 at 100 µM) of PGE2 production (Figure 6C) with an IC50 of 9.85 µM (r2 = 0.966) as well as of cPLA2 translocation to the membrane compartment (Figure 6D). Thus, our data strongly support an inhibitory action of zileuton at the level of AA release mediated by stimuli such as LPS and zymosan and not by calcium ionophore A23187.

Figure 6.

Effects of zileuton on the release of radioactivity from [3H]-AA-labelled peritoneal macrophages, PGE2 production and cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) translocation. Zileuton failed to inhibit radioactivity release from [3H]-AA-labelled peritoneal macrophages stimulated with Ca2+-ionophore A23187 (1 µM) for 1 h (A). Zileuton significantly inhibited radioactivity release (B) from [3H]-AA-labelled cells, PGE2 (measured by radioimmunoassay) (C) and cPLA2 translocation (D) in peritoneal macrophages activated with zymosan (30 particles·cells−1) for 1 h. Background release from unstimulated cells was about 2%. Radioactivity release was determined and expressed as a percentage of the total radioactivity (cell-associated plus media). Data are expressed as means ± SEM from three separate experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001 versus unstimulated cells (c), °P < 0.05; °°P < 0.01; °°°P < 0.001 versus cells activated with zymosan in absence of zileuton. Cell lysates and Western blot analysis were performed as described (see Materials and Methods). The illustrated blots are representative of at least three separate experiments.

Discussion and conclusions

Zileuton is currently approved by the FDA for the prophylaxis and chronic treatment of asthma in adults and children older than 12 years. Several studies indicate that zileuton is a specific inhibitor of 5-LOX, resulting in the suppression of LT production (Berger et al., 2007). In this study, we found that, besides inhibition of LTs, zileuton also produced a significant decrease of PG production in vitro (thioglycolate-elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages activated with LPS/IFNγ or zymosan and murine J774 macrophages activated with LPS), as well as in a biologically relevant test system, i.e. human whole blood, and in vivo (carrageenan-induced pleurisy). Also, we identified the release of AA by cPLA2 as the possible target of zileuton action.

Zileuton is the only commercially available inhibitor of 5-LOX (Zyflo®). In clinical trials, it has been shown to induce acute bronchodilator effects, likely related to inhibition of cysLTs and their action on bronchial smooth muscle tone. However, zileuton also provides a chronic improvement of airway functions, associated with a reduction of inflammatory components of asthma, such as oedema, cellular infiltration and mucus production (Drazen et al., 1999), and decreases the dose of anti-inflammatory glucocorticoids required to control asthma. Notably, although doses of zileuton of 400 and 600 mg were equally effective for acute improvement of pulmonary functions, a significant improvement of chronic airway function was observed only after four times daily administration of 600 mg compound (Liu et al., 1996). Therefore, the recommended oral dosage of zileuton for treatment of asthma is 4 × 600 mg·day−1 (or 2 × 1200 mg·day−1 for the recently approved extended release tablets, Zyflo CR®), for a total daily dose of 2400 mg, resulting in plasma peak levels of about 5 µg·mL−1 (corresponding to about 21 µM) and systemic exposure (mean area under curve) of 19.2 µg·h·mL−1. Although a 93% binding to plasma proteins has to be taken into account, these plasma concentrations clearly exceed the IC50 values for 5-LOX in the blood (i.e. 0.5 to 1 µM), and the contribution of effects on other targets to the overall action of zileuton is a reasonable possibility.

Here, we show that zileuton inhibits PG production in vitro (mouse peritoneal macrophages, J774 macrophages, human whole blood) as well as in vivo (carrageenan-induced pleurisy in rats). In particular, the observed IC50 for inhibition of PGE2 in LPS-stimulated whole blood was around 13 µM. Thus, although the IC50 value for PG biosynthesis is higher in comparison to those reported for 5-LOX, it clearly reflects pharmacologically achievable concentrations by the standard doses of zileuton (plasma peak level of 21 µM) (Dube et al., 1998) despite 93% binding to plasma proteins.

The possible implications of these findings in patients undergoing asthma therapy with zileuton and if inhibition of PGs may (or may not) partially account for the chronic improvement of airway inflammation (oedema, cellular infiltration) observed in these patients remain to be determined during clinical treatment. In fact, it remains to be established if the concentration achieved by the recommended oral doses of zileuton for treatment of asthma effectively inhibits PG production in patients, by, for instance, measuring urinary excretion of PGs and PG metabolites. In this regard, it has to be noted that a decreased amount of prostanoids has been observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of antigen-challenged ragweed-allergic human subjects treated with standard doses of zileuton (Kane et al., 1995).

We observed a reduction of PGE2 levels of about 50% in the pleural exudates of carrageenan-treated rats by i.p. treatment with zileuton (10 mg·kg−1). A similar inhibition was found for LTB4 (∼60%) and the treatment with the compound significantly attenuated the inflammatory reaction, measured as exudate volume and number of infiltrating cells. Notably, i.p. treatment with 1.5 mg·kg−1 MK-886 (an inhibitor of the 5-LOX activating protein), which also resulted in a stronger inhibition of LTB4 levels than zileuton (∼75%), did not influence PG production and had only moderate effects on plasma exudation and cellular infiltration. Therefore, it appeared likely that the anti-inflammatory effects of zileuton are not only restricted to reduction of LT formation but might partially also depend on inhibition of prostanoids. For instance, the COX inhibitor indomethacin, which instead suppressed pleural PGE2 levels without affecting LTB4, efficiently reduced exudate volume and cell number.

An inhibitory effect of zileuton on the levels of prostanoids has been previously observed in certain in vivo experimental models. In particular, it has been shown that Zyflo® reduced PGE2 concentrations in liver metastases of N-nitrosobis-2-oxopropylamine-induced pancreatic carcinoma in Syrian Golden hamsters (Gregor et al., 2005) and decreased PGE2 levels in rat oesophageal adenocarcinoma (Chen et al., 2004). However, the in vitro and in vivo effects of zileuton reported in the literature are conflicting (Berger et al., 2007) and these observations have neither been explained nor further explored.

Here, we have investigated the biochemical mechanism of the inhibitory effect of zileuton on PG production in vitro. According to previous results (Rossi et al., 2005), one of the possible mechanism/s could be related to the positive modulation of LTs on PG production. Thus, suppression of LT formation by zileuton would result in a consequent inhibition of prostanoid biosynthesis. However, this mechanism may only partially account for inhibition of PG production by zileuton. This was supported by the following findings: (i) significant inhibition of PGs was observed at concentrations of zileuton higher than those required for a complete suppression of 5-LOX activity; (ii) as observed in peritoneal macrophages from 5-LOX WT mice activated with LPS/IFNγ, zileuton inhibited PGE2 production also in cells from 5-LOX KO mice, although with a slightly higher IC50; (iii) zileuton inhibited PG production also in J774 macrophages which do not produce detectable amount of LT following stimulation with LPS; (iv) MK-886 (1.5 mg·kg−1, i.p.), which also reduced the in vivo production of LTB4, failed to decrease PG levels. Thus, the inhibition of prostanoid biosynthesis by zileuton might only partially depend on suppression of LTs (and therefore on a decreased LT action on the COX pathway) and seems to be rather related to a direct action at the level of one of the steps of the AA cascade leading to PG biosynthesis.

During an inflammatory insult, PLA2 releases AA from cell membrane phospholipids, which is subsequently metabolized through a series of enzymatic reactions to yield biologically active mediators. COX enzymes convert AA into PGH2, which is further metabolized by terminal PG synthases to PGE2, 6-keto PGF1α, PGD2, PGF2α and thromboxane A2. Since mPGES1 is an efficient downstream enzyme for the production of PGE2 in LPS-activated macrophages (Lazarus et al., 2002), zileuton might target mPGES1 and consequently inhibit PGE2 formation. Our results (inhibition of 6-keto PGF1α by zileuton in LPS/IFNγ activated peritoneal macrophages and LPS-activated J774 macrophages as well as the failure of zileuton to inhibit mPGES1 activity in a cell-free assay) demonstrated that the action of zileuton on PGE2 production occurred through a different mechanism. In addition, interference with COX-2, the main COX isoform responsible for prostanoid production in LPS/IFNγ-stimulated peritoneal macrophages and in LPS-stimulated J774 macrophages (Brock et al., 1999), can be excluded, since zileuton neither affected COX-2 expression nor its activity in a cell-free assay. Hence, a possible point of attack of zileuton could be the release of AA, which represents the initial and rate-limiting step in eicosanoid biosynthesis. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that zileuton failed to inhibit PG formation in the presence of exogenous AA and was finally confirmed by the finding that zileuton inhibited the release of AA from macrophages induced by LPS or zymosan. Importantly, the IC50 observed for inhibition of AA release in LPS-stimulated J774 macrophages (3.5 µM) is consistent with those observed for inhibition of PGE2 (1.94 µM) or 6-keto PGF1α (5.8 µM).

The inhibitory action of zileuton on the release of AA from membrane phospholipids was not related to a direct effect on cPLA2 activity (as assessed in a cell-free assay of purified human recombinant cPLA2) but seemed to depend on the inhibition of cPLA2 translocation to the membranes, a movement crucial for the cellular activation of the enzyme (Gijón and Leslie, 1999). It is well known that increases in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinases are involved in cPLA2 activation in macrophages (Gijón et al., 2000). Interestingly, zileuton prevented AA release when physiopathologically relevant stimuli were used (LPS or zymosan), but no significant effects were observed when the Ca2+-ionophore A23187 was utilized. These data suggest an interference with a mechanism independent of Ca2+ and suggest further evaluation of other relevant stimulatory conditions. Notably, many of the data concerning the selective inhibition of 5-LOX by zileuton result from the use of calcium ionophore A23187 as stimulus for eicosanoid production (Carter et al., 1991; Bell et al., 1992) and the effect on AA release and prostanoid biosynthesis might have been overcome. However, further investigations are needed to elucidate the precise mechanism of the action of zileuton.

The finding that zileuton inhibits AA release has several important implications. First, the overall inhibition of 5-LOX products by zileuton seems to be due, at least in our experimental models, to two different mechanisms: (i) the well known direct effect on 5-LOX activity, and (ii) the reduction of AA availability. Second, suppression of PG production by zileuton has to be carefully taken into account when considering its action in experimental models of inflammation. Third, in cell types metabolizing AA to other products than LTs and PGs (i.e. cytochrome P450 monooxygenase pathways) (Specto, 2009), zileuton might also affect their formation with additional important implications.

In the light of these considerations, the effect on PG production should be considered when the drug is utilized as a pharmacological tool to evaluate the role of LTs. For example, the role of 5-LOX metabolites in carcinogenesis (Chen et al., 2006) has been addressed using zileuton and it has been demonstrated that it exerts beneficial effect in several experimental in vivo models of cancer (Gregor et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005). Since the important role of PG in tumour initiation and progression is well known, the effects responsible for the positive action of zileuton should be carefully reassessed.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that zileuton inhibits PG production by interfering at the level of AA release and suggest that its mechanism of action as well as its use as pharmacological tool in different experimental models of inflammation should be re-evaluated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Italian MIUR and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support. C.P. received a Carl-Zeiss stipend.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 5-LOX

5-lipoxygenase

- AA

arachidonic acid

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- cPLA2

cytosolic phospholipase A2

- cysLTs

cysteinyl leukotrienes

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GSH

glutathione

- IFNγ

interferon γ

- KO

knockout

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MLVs

multilamellar vesicles

- mPGES1

microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- OD

optical density

- PG

prostaglandin

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- WT

wild type

Conflicts of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information: Teaching Materials; Figs 1–6 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl. 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierschmitt WP, McNeish JD, Griffiths RJ, Nagahisa A, Nakane M, Amacher DE. Induction of hepatic microsomal drug-metabolizing enzymes by inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO): studies in rats and 5-LO knockout mice. Toxicol Sci. 2001;63:15–21. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/63.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Young PR, Albert D, Lanni C, Summers JB, Brooks DW, et al. The discovery and development of zileuton: an orally active 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1992;14:505–510. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(92)90182-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger W, De Chandt MT, Cairns CB. Zileuton: clinical implications of 5-lipoxygenase inhibition in severe airway disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:663–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock TG, McNish RW, Peters-Golden M. Arachidonic acid is preferentially metabolized by cyclooxygenase-2 to prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11660–11666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter GW, Young PR, Albert DH, Bouska J, Dyer R, Bell RL, et al. 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of zileuton. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;256:929–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho MS, McCormack FX, Leslie CC. The 85-kDa, arachidonic acid-specific phospholipase A2 is expressed as an activated phosphoprotein in Sf9 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;306:534–540. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang S, Wu N, Sood S, Wang P, Jin Z, et al. Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase in rat and human esophageal adenocarcinoma and inhibitory effects of zileuton and celecoxib on carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;10:6703–6709. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Sood S, Yang CS, Li N, Sun Z. Five-lipoxygenase pathway of arachidonic acid metabolism in carcino-genesis and cancer chemoprevention. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:613–622. doi: 10.2174/156800906778742451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin M, Rossi A, Cuzzocrea S, Patel NS, Di Paola R, Hadley J, et al. Reduction of the multiple organ injury and dysfunction caused by endotoxemia in 5-lipoxygenase knockout mice and by the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:961–970. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0604338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Rossi A, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, Genovese T, Muià C, et al. 5-Lipoxygenase modulates colitis through the regulation of adhesion molecule expression and neutrophil migration. Lab Invest. 2005;85:808–822. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazen JM, Israel E, O'Byrne PM. Treatment of asthma with drugs modifying the leukotriene pathway. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:197–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube LM, Swanson L, Awani WM, Bell RL, Carter GW. Zileuton: the first leukotriene synthesis inhibitor for use in the management of chronic asthma. In: Drazen JM, Dahlen SE, Lee TH, editors. Lung Biology in Health and Disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998. p. 391. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese T, Rossi A, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, Muià C, Caminiti R, et al. Effects of zileuton and montelukast in mouse experimental spinal cord injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:568–582. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijón MA, Leslie CC. Regulation of arachidonic acid release and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:330–336. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijón MA, Spencer DM, Kaiser AL, Leslie CC. Role of phosphorylation sites and the C2 domain in regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1219–1232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijón MA, Spencer DM, Siddiqi AR, Bonventre JV, Leslie CC. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is required for macrophage arachidonic acid release by agonists that Do and Do not mobilize calcium. Novel role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in cytosolic phospholipase A2 regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20146–20156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908941199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor JI, Kilian M, Heukamp I, Kiewert C, Kristiansen G, Schimke I, et al. Effects of selective COX-2 and 5-LOX inhibition on prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis in ductal pancreatic cancer in Syrian hamster. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad AM, Sutcliffe AM, Knox AJ. Aspirin-induced asthma: clinical aspects, pathogenesis and management. Drugs. 2004;64:2417–2432. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson PJ, Thorén S, Morgenstern R, Samuelsson B. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane GC, Tollino M, Pollice M, Kimm CJ, Cohn J, Murray JJ, et al. Insights into IgE-mediated lung inflammation derived from a study employing a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Prostaglandins. 1995;50:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(95)00088-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knospe J, Steinhilber D, Herrmann T, Roth HJ. Picomole determination of 2,4-dimethoxyanilides of prostaglandins by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr. 1988;442:444–450. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)94498-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak HJ, Park KM, Choi HE, Lim HJ, Parkm JH, Park HY. The cardioprotective effects of zileuton, a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, are mediated by COX-2 via activation of PKCdelta. Cell Signal. 2010;22:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus M, Kubata BK, Eguchi N, Fujitani Y, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Biochemical characterization of mouse microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 and its colocalization with cyclooxygenase-2 in peritoneal macrophages. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:336–341. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Sood S, Wang S, Fang M, Wang P, Sun Z, et al. Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase 2 in hamster and human oral cancer and chemopreventive effects of zileuton and celecoxib. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2089–2096. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MC, Dubé LM, Lancaster J. Acute and chronic effects of a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor in asthma: a 6-month randomized multicenter trial. Zileuton Study Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:859–871. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assay. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunoshiba T, deRojas-Walker T, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR, Demple B. Activation by nitric oxide of an oxidative-stress response that defends Escherichia coli against activated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9993–9997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Intracellular compartmentalization of leukotriene biosynthesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S36–S40. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_1.ltta-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR., Jr Leukotrienes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1841–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi A, Acquaviva AM, Iuliano F, Di Paola R, Cuzzocrea S, Sautebin L. Up-regulation of prostaglandin biosynthesis by leukotriene C4 in elicited mice peritoneal macrophages activated with lipopolysaccharide/interferonγ. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:985–991. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1004619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautebin L, Ianaro A, Rombola L, Ialenti A, Sala A, Di Rosa M. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent generation of 8-epiprostaglandin F2α by lipopolysaccharide-activated J774 macrophages. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:503–508. doi: 10.1007/s000110050494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seno K, Okuno T, Nishi K, Murakami Y, Watanabe F, Matsuura T, et al. Pyrrolidine inhibitors of human cytosolic phospholipase A(2) J Med Chem. 2000;43:1041–1044. doi: 10.1021/jm9905155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemoneit U, Hofmann B, Kather N, Lamkemeyer T, Madlung J, Franke L, et al. Identification and functional analysis of cyclooxygenase-1 as a molecular target of boswellic acids. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specto AA. Arachidonic acid cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:52–56. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800038-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli S, Capone M, Sciulli M, Ricciotti E, Patrignani P. The biochemical selectivity of novel COX-2 inhibitors in whole blood assays of COX-isozyme activity. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18:503–511. doi: 10.1185/030079902125001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorén S, Jakobsson PJ. Coordinate up- and down-regulation of glutathione-dependent prostaglandin E synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in A549 cells. Inhibition by NS-398 and leukotriene C4. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6428–6434. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.