Abstract

Data from interviews with staff of government offices, relevant literature and national statistics are used to analyze laws, regulations, rules, policies and operational procedures concerning birth registration in China. The current status of and existing problems with birth registration, as well as the influences of delayed birth registration on children’s rights and welfare are examined. Finally, barriers to birth registration in China are explored and strategies to improve the process of birth registration and to protect children’s rights are proposed. The main findings are as follows: First, the rate of birth registration in China is low and in rural areas and for marginalized children, it is even lower. Second, the dual birth registration system and interference from the Population and Family Planning department cause serious administrative difficulties. Third, the serious problems surrounding birth registration in China are a result of interactions among the interests of different stakeholders, while most stakeholders are unaware of the dimensions of the problems. Strategies and policies to promote birth registration are discussed.

Keywords: Birth registration, migration policy, children’s rights, bureaucratic conflicts, rural-urban differences

BACKGROUND

Birth registration (BR), a permanent and official record of a child’s existence, is the process by which a child’s birth is recorded by a particular government department. According to the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), a child should be registered immediately after its birth.

Among the international community, protection of human rights, especially the rights of vulnerable groups, including children, has attracted increased attention. Children are an especially vulnerable group who lack the awareness and ability to protect themselves, and whose rights are often violated by adults and society as a whole. Protection of children’s rights has become the most serious problem among the world’s vulnerable groups, and assurance of their protection can help in the sustainable development of most of the world’s population (Jiang et al., 2004; Li and Zhu, 2005).

BR is a basic right of each child and a fundamental step towards acquiring citizenship and nationality, as well as realizing other human rights. Registering a child is not only the duty of the child’s guardian, but also the public responsibility of the government (Liu, 2004). A child without BR cannot prove his or her legal existence before the law; consequently, his or her survival, protection, participation, and development in society will be negatively affected (UNICEF, 2002; Youth Advocate Program International, 2002).

Although BR has far-reaching significance for the protection of children’s rights and social development, there remain large numbers of children throughout the world without BR. For economic, cultural, administrative, and political reasons, this problem is particularly acute in developing countries and underdeveloped areas. In general, rates of BR in rural areas are lower than in urban areas. According to UNICEF, an estimated 50 million new born babies (41% of the total births) in the world were not registered in 2000, and among these, 40% lived in South Asia, 34% in Sub-Sahara Africa, and 14% in the Middle East/North Africa region. The fractions of births not registered in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Middle East/North Africa, East Asia/Pacific, Latin America/Caribbean, and CEE/CIS region were 71%, 63%, 31%, 22%, 14%, and 10%, respectively (UNICEF, 2002). In 2004, there were 48 million new babies (36% of the total births) born in the world without registration. South Asia and Sub-Sahara Africa remained the two worst regions in terms of the unregistered rate at 63% and 55%, respectively. By contrast, only 2% of births were not registered in industrialized countries (UNICEF, 2004; PLAN, 2005). In order to improve BR, since the 1990s, the international community has been paying more attention to BR and taken many practical measures to increase the rate. Nevertheless, the BR situation around the world remains serious.

In China, BR refers to the system that records a child’s birth, testifies to its citizenship, and registers its permanent residence, known as Hukou, by the household registration department (Wang, 2001). Hukou registration is the only symbol that BR has been carried out and completed, and Hukou registration is one of the most important components of the household management system in China. A child cannot acquire most of his or her rights without Hukou registration. The references that need to be provided when applying for BR include a medical birth certificate (MBC) issued by the Public Health (PH) department, a birth certificate (BC) issued by the Population and Family Planning (PFP) department, and the parents’ Hukou booklets or identity cards issued by Public Security (PS) departments.

China also has a large number of unregistered children. According to a report by UNICEF, in 19 countries including China, 26% to 60% of children less than five years old were not registered (Deen, 2002). China has the largest population in the world, and in 2000 there were about 346 million children in the country, accounting for 27.79% of its population (Xu, 2008). Thus, even though the unregistered rate is not the highest in the world, the number of unregistered Chinese children is huge and the rights to survival and development of these unregistered children will be seriously violated. However, besides a few articles concerning legislation, and regulations and rules* about BR, there has been no systematic study of BR in China (Liu, 2004).

During 2004 and 2005, the Institute for Population and Development Studies at Xi’an Jiaotong University, in cooperation with Plan International (China), an international, child-centered and non-governmental development organization, made an exploratory investigation of BR in China. This investigation has led to the present analysis of BR in China from the perspectives of history, the current situation, and problems. We also address the influences of delayed BR on children’s rights and welfare; discuss barriers to BR; propose strategies and policies to facilitate children’s BR and to protect children’s rights; and provide a possible reference point for the promotion of children’s BR throughout the world.

STUDY DESIGN

Framework

Qualitative methods, assisted by quantitative methods, are employed to analyze BR at the macro and micro-levels. Since the PFP, PH, and PS departments are all involved in BR procedures, these three departments are studied at each administrative level.

The macro-level research was carried out on both national and provincial levels since the relevant departments at these two levels are decision-making entities, but assume different responsibilities. In China, the main responsibility of national departments is to propose the general laws, regulations, and rules, while that of provincial departments is mainly to supplement these with regulations and rules appropriate to local situations. Furthermore, with its vast area and different geographic, economic, and cultural environments, provincial differences with respect to BR in China are inevitable and require that the macro-study of BR be carried out at both national and provincial levels. In this paper, three provinces, province S located in the Yellow River Valley, province A in the Yangtze River Valley, and province Y on the south-western border of China, with a large number of national minorities, were selected for investigation.

The micro-level research was conducted at county (or urban district) and township (or sub-district) levels. The departments at these two levels have different responsibilities; the main duties of county and district departments are administrative, while the responsibilities of township and sub-district departments are to actually carry out registration. Furthermore, because of the significant differences between urban and rural areas in policies, economy, culture, and management, the micro studies were done in both rural and urban areas. The rural study was carried out in County CH of province S and three towns of County CH, while the urban study took place in two urban districts and three sub-districts of the two urban districts in City X of province S. However, our primary focus is the rural situation.

Data and Methods

For qualitative study, the data were collected by reviewing relevant documents and literature on BR and interviewing officials from government departments. For quantitative study, birth data recorded by relevant departments were collected.

First, documentation concerning national laws, regulations and rules related to BR, and provincial regulations and rules for three selected provinces after 1950, are reviewed. Second, in order to explore the gap between laws, regulations and rules concerning BR on the one hand and the manipulation, history and current status of BR, barriers to BR, consequences of delayed BR and lack of registration, and suggestions for promoting more universal BR on the other, interviews with officials from government departments at different level were carried out between October 2004 and April 2005. These included group discussions and in-depth interviews with 248 directors and staff members in charge of BR from the PFP, PH, and PS departments of the central government, the three selected provinces (Y, S, and A), County CH and City X, three townships of County CH, two districts and three sub-districts of these two districts in City X. A group discussion usually lasted about two hours, and an in-depth interview about forty minutes. Focus-group and main topic discussions were both employed in group settings. After the interviews, notes and records of all interviews were immediately processed, and subsequently analyzed using the method of classification (Chen, 2000). The outlines of and interviewees involved in all interviews are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Outlines of Different Interviews

| PS department | PH department | PFP department | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National |

|

|

|

| Provincial |

|

|

|

| County (district) and township (sub-district) |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Interviewees in all Interviews

| PS departments | PH departments | PFP departments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | Individual interviews | 2 persons | 2 persons | 4 persons | |

| Provincial | Province S | Individual interviews | 5 persons | 5 persons | 5 persons |

| Group discussions | 1 group (7 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | |||

| Province A | Individual interviews | 5 persons | 5 persons | 5 persons | |

| Group discussions | 1 group (7 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | ||

| Province Y | Individual interviews | 5 persons | 7 persons | 5 persons | |

| Group discussions | 1 group (10 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | |||

| County (district) and township (sub-district) | County CH | Individual interviews | 22 persons | 19 persons | 20 persons |

| Group discussions | 1 group (10 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | ||

| City X | Individual interviews | 5 persons | 8 persons | 7 persons | |

| Group discussions | 1 group (8 persons) | 1 group (10 persons) | |||

In order to evaluate the BR situation in China, birth data recorded by the national PFP and PS departments and our adjusted birth data from 1991 to 2000 are compared. Because birth data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China and national censuses, are not always accurate, we do not use these data directly. Instead, using the method of Li et al. (2006), we estimate the numbers of over-counted and under-reported people in the 2000 census and then adjust the births from 1991 to 2000 using reverse survival analysis and reference time analysis.

HISTORY AND CURRENT STATUS OF BR

Laws, Regulations and Policies

The relevant laws, regulations, and rules concerning BR issued nationally after 1950 are analyzed in three phases, according to the major social and economic changes that occurred in China and that appear to have had a big impact on BR. The differences among regulations and rules modified and/or added by the three selected provinces are discussed as well.

National laws, regulations and policies

The period of economic recovery: from 1949 to 1957

The document ‘Regulations on Hukou Registration for Urban Citizens’ issued in 1951 was the first concerning BR in the PRC, and stated that each newborn baby must be registered at the local police station by his/her parents or guardians within one month after its birth. But for rural areas, the BR system was established in 1953 based on the first national census of that year and was managed by township governments. Thus, a dual Hukou administrative system, urban and rural, emerged and lasted about 40 years.

The main purposes of BR during this initial period of the PRC were to provide vital statistics, to guarantee public security, and to aid in the fight against perceived hostile forces (Wang, 2002). The policies concerning BR were seriously flawed and the BR rate was not high during this period.

The period of planned economy:from 1958 to 1977

The document ‘Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Hukou Registration’, issued in 1958, was an important symbol of the formal establishment of a unified administrative policy for urban and rural Hukou registers. It stipulated that the household heads, relatives, foster parents or neighbors of the newborn baby should apply for its BR within 30 days after the birth at the Hukou registry office at the place of the baby’s permanent residence. It also prescribed that the Hukou administrative departments were the PS departments and that the registry offices in urban areas were the police stations, while in rural areas, the township People’s Committees were responsible for Hukou registration (Lu, 2004). These rules affirmed the principle that Hukou should be registered at the place of legal permanent residence, and they simultaneously consolidated the dual Hukou rural-urban system. Although the ‘Hukou Registration Regulations’ prescribed the time limit of Hukou registration as within thirty days after birth, the ministry of PS stressed that the time limit of Hukou registration for rural areas could be extended according to what was practically reasonable. Thus some places extended the time limit for Hukou registration to within three months after birth or even longer.

According to our interviews, during this period, in order to accommodate the priority of developing heavy industry, the needs of the planned economy, and the shortage of national resources, the government tied Hukou to many benefits. As a result, residents of urban areas enjoyed priority in allocation of benefits and resources over those in rural areas, and the difference between urban and rural areas became increasingly apparent. However, people in both urban and rural areas placed great emphasis on Hukou registration since the Hukou had a great deal to do with the allocation of people’s basic supplies. BR situation during this period was much better than in all other periods.

The period of the market economy: from 1978 to the present

At the end of the 1970s, after the implementation of Family Planning policies, BR became an effective measure to control China’s population increase, and a BC became a necessary reference for BR. Family Planning policies seriously affected BR of out-of-plan children for a while. In the 1980s, China began to implement strictly the policy stipulating that the baby should be registered at the mother’s designated residence (Huang, 1999). This restricted the child’s right to be registered at a place with better living conditions, to select better schools and, later, to freely seek a job. Later, MBC became another prerequisite for BR after the ‘Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Maternal and Infant Health Care’ was issued in 1996.

Since economic reform and opening-up, especially the establishment and development of the market economy, the Chinese government gradually began to modify the earlier system of Hukou registration as its disadvantages became increasingly obvious. In 1996, the Ministry of PS issued ‘30 Convenient Measures for People’, which stipulated that a newborn baby could be registered at either the mother’s or the father’s designated residence. Then, ‘Opinions of the Ministry of PS on Improving the Administrative System of Hukou in Rural Areas’ was issued in 1997 requiring that the Hukou registration systems in rural and urban areas be unified. From then on, the administration of Hukou in rural areas gradually became standardized. The ‘Opinions’ also permitted out-of-plan children and children of unmarried couples to receive BR, which reduced the influence of Family Planning policies on BR. However, because of the loose connection between Hukou and allocation of people’s basic supplies, people today pay less attention to BR, and the rate of BR is gradually declining, especially in rural areas.

In conclusion, since 1950 the BR system in China has evolved from focusing only on urban BR to paying equal attention to rural BR, and from neglecting the child’s rights to caring for them. The BR system, and Hukou registration system to which the BR is attached, have been changing continuously because they are not independent systems and are affected easily by other rules or measures relating to the different national priorities in different periods. As a result the BR and Hukou registration systems exceed their primary functions of protecting human rights and providing statistical data on the composition of population, with profoundly negative impacts on BR. Since economic reform and opening-up, the state has modified the systems of BR and Hukou registration greatly, but not completely. Hukou remains an important indicator of allocation of resources, benefits and responsibilities, as well as a measure to manage migration. The rural-urban duality of the Hukou administrative system has essentially not changed (Ma, 2000; Lu, 2001).

Differences in provincial regulations and rules of the three selected provinces

Because of China’s highly centralized state power and the low priority attached by provincial governments to BR, differences between regulations and rules concerning BR based on national legislation and regulations in the three provinces we studied are not great. The main reasons for differences among provinces are the extent of economic development, the family planning status, and the status of minority nationalities. For example, in province S, the majority of the population is rural, and in order to prevent a large number of rural people from settling in cities, additional restrictive terms were appended to the Hukou registration of a child applying for registration at the place of its father’s residence. The intention was to prevent the child from obtaining registration in a city with its father. Province A has been stricter than all other provinces in the administration and implementation of Family Planning policies according to the national assessment, and this has greatly affected BR there. For instance, even after the relevant measures issued by the Ministry of PS allowed out-of-plan children to receive BR without any restriction, the government of province A, in order to control population increase, still dictated that the PS departments should transmit the out-of-plan child’s BR information to PFP departments so as to punish couples for bearing out-of-plan children. In province Y with a great number of minority nationalities, the BR system has great flexibility. Generally, the national laws, regulations and rules concerning BR are passed down directly to the subordinate departments, and the subordinate departments then set specific measures to implement those laws and regulations. There are few regulations and rules that are modified and/or added to by provincial departments in province Y.

BR Procedure

Because of China’s highly centralized state power the local governments keep in line with the central government, so the specific procedures of BR stipulated by three provinces are not very different.

Evolution of BR procedure

From our interviews, it was known that during the early days of the PRC, the state did not propose any specific rules concerning the references needed to apply for BR. Along with the ‘Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Hukou Registration’ issued in 1958, the parents’ Hukou booklets became the necessary references for children applying for BR at local police stations in urban areas. But children in rural areas could be registered by the village committee without any references, and the registration was then reported to the township committee by the leader of the village. Since 1979, a BC issued by the PFP department became a necessary reference in applying for BR in both urban and rural areas, and an out-of-plan child has had to provide proofs of payment of the penalty (or the social support fees) to the PFP departments. In recent years, all provinces have gradually relaxed the requirements on BC, and most provinces even permit the first child to apply for BR without BC. Since 1996, a MBC issued by the PH department has become another necessary reference for children in urban areas as well as in some rural areas that implement urbanized management of Hukou registration.

It can be seen that the BR procedure has gradually become standardized, which should have facilitated improvement in BR rates. On the other hand, the increased number of references required in the BR procedure has had a negative influence on the rate of BR, especially since BC became a requirement to apply for BR.

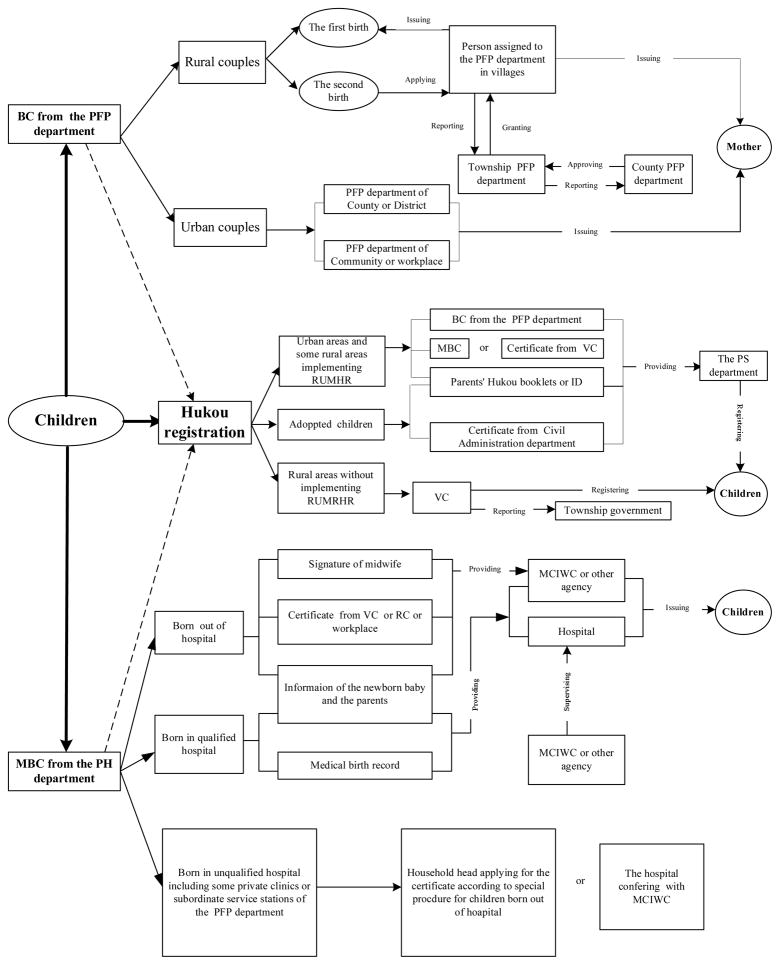

Current BR procedure

Today, the BR procedure remains very complex and three references are involved in BR application. As Figure 1 shows, the couple first needs to apply for the BC from the PFP department during the period of pregnancy and then for the MBC from the PH department after birth. Only with these two references, can they register Hukou for the child at their local police station with their Hukou booklets. For an adopted child, the foster parents cannot register Hukou for the adopted child unless they receive adoption documentation following special adopting procedures that are very strict. However, the government bureaus make these procedures simpler during national and local censuses.

Figure 1. Outline of the procedure of BR in China [UMRHR misspelled twice above].

Notes: BC, Birth Certificate; MBC, Medical Birth Certificate; PFP, Population and Family Planning; PS, Public Security; PH, Public Health; VC, Village Committee; RC, Residence Committee; UMRHR, Urbanized Management of Rural Hukou Register; MCIWC, Medical Care Institution for Women and Children.

It can be seen in Figure 1 that the BR procedures in urban and rural areas are very different. In practice, the BR procedure in rural areas is much less standardized than that in urban areas, and the operational capability of registry departments in rural areas is also much worse than that in urban areas. In general, multiple and independent registration procedures for different certificates, isolated registry sites, and independent administration of different registry departments cause great inconvenience to applicant.

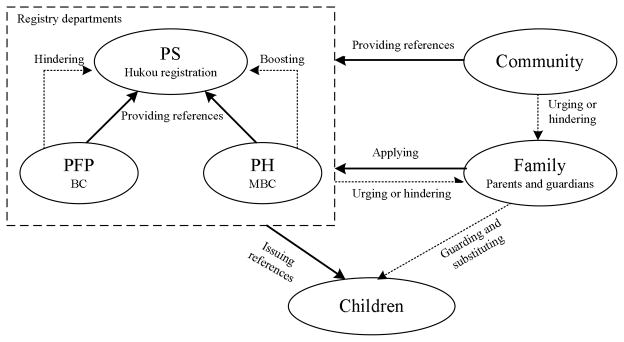

More importantly, because the stakeholders have no common goal, and because the child plays no role in BR, as his or her parents or guardians act as the agents, all other stakeholders, including the registry departments, the communities and parents or guardians, undertake their responsibilities from the perspective of protecting their own interests rather than from the perspective of protecting children’s rights. This results in a complicated relationship among the stakeholders and consequently many barriers to BR. Figure 2 shows the relationships among the stakeholders involved in BR.

Figure 2. Relationships among stakeholders involved in BR.

The BR Situation

Estimation of BR rate

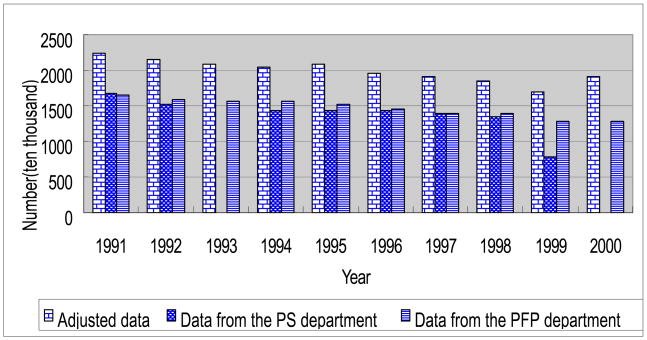

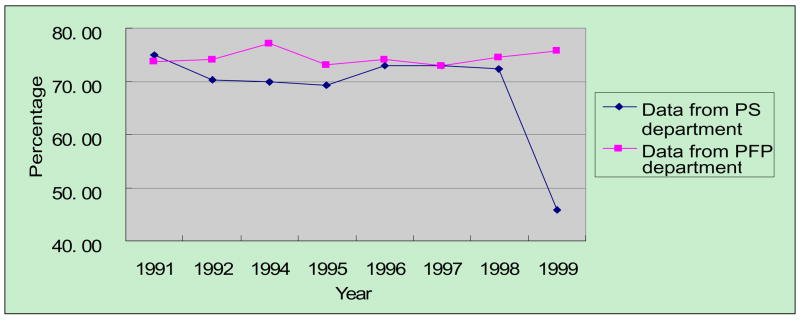

In Figures 3 and 4, the births from 1991 to 2000 in China recorded by PS and by PFP departments, and those adjusted by us using reverse survival and reference time analysis as in Li et al. (2006), are compared in order to estimate the BR rates during this period.

Figure 3. Comparison of birth statistics, 1991–2000.

Sources: Our adjusted data; PFP Communique; Vital statistics of cities and counties of PRC

Note: Statistics from PS department in 1993 and 2000 are not available

Figure 4. Fraction of PS department’s and PFP department’s birth data (%)of our adjusted data, 1991–2000.

Sources: Same as Figure 3

Referring to our adjusted data for births in this paper, Figures 3 and 4 show that the PFP department recorded only 60%–80% of the births from 1991 to 1999, which means that 20%–40% children were not registered in the year they were born. The registration rate through the PS system was even lower, especially in 1999, when the registered births were less than 50% of our adjusted births. According to our interviews, one possible reason for this may be that a large number of parents waited to register their children at the 5th national census in 2000, since the BR procedure at that time was much simpler and cheaper, and parents of out-of-plan children did not have to pay social support fees. However, as the birth statistics from PS department in 2000 are not available, validation of such inferences will require further investigation.

BR level in County CH and in City X

From our interviews, we found that County CH has delayed the deadline for BR in rural areas to 3 months after birth according to the national documentation ‘Regulations of the People’s Republic China on Hukou Registration’, while for urban areas it remains 1 month. In recent years, less than 30% of children in County CH were registered within three months after birth, and less than 50% of children were registered within one year after birth.

In city X, in recent years, the rate of urban children’s BR within their first year of life has been about 80%, but the rate within one month after birth is much lower. Children, both of whose parents’ Hukou were registered at city X, are usually registered within three months after birth, while children not registered within one year of their birth are generally from families in which the mothers’ Hukou are not registered at city X. The main reason for this is that some families expect to take the opportunity to register children at City X where their fathers are from, while some mothers might not be able to return to their designated residence to register their children on time.

Features of BR

BR in China has special characteristics that differentiate it from BR in other countries. First, in practice there is a dual Hukou registration system with differences between urban and rural areas. The Hukou is closely related to the allocation of benefits and resources and differentially identifies people coming from rural and urban areas. Second, at least three registry departments, PS, PFP, and PH departments, are involved in BR; in particular, the involvement of the PFP department and its direct contribution to the fate of out-of-plan children does not occur in other countries. Third, the registration process is very complex and the procedures for BC, MBC, and Hukou application differ from one another. In addition, there are many other stakeholders involved in the BR procedure in addition to the three registry departments, such as children, parents or guardians of children, families, and communities, etc. Fourth, there is China’s unique cultural environment including the norms that ‘father is son’s lord’, and ‘son preference’, which have strong negative influences on BR of girls under the Family Planning policy. Fifth, the laws, regulations and rules concerning BR, traditional culture, economic development, public awareness, and practical registration processes, differ greatly between urban and rural areas; as a result, the situation in cities is much better than in the countryside. However, differences in BR among provinces are not great, and mainly concern regulations that have been modified and/or expanded by the provinces. The dual Hukou registration system and the involvement of PFP department are features of BR that are probably unique to China.

Problems and Consequences

The problems

First, statistics and our interviews indicate that the rate of BR in China is not high, especially in poor and remote areas, and in rural areas it is much lower than in urban areas. According to our interviews, less than 20% of rural children are registered within one month after birth, and less than 50% of children within one year after birth, much lower than in urban areas. Since, rural children are a large percentage of all children in China, the low BR rate in rural areas accounts for a major part of the current deficient BR situation. Further, the BR level for girls is lower than for boys. For example, in 2004, in province A, a special check of the unregistered population over the previous ten years was carried out by the PFP department, and about 530,000 unregistered people were identified, of whom 70–80% were females. Many regions are facing the same problem, but to different extents. The BR situations of the migrant workers’ children, out-of-plan children, and adopted children are even worse. Currently, the number of migrant workers and their families in China exceeds 100 million (www.chinanews.cn/news/2004/2005-01-06/772.shtml., 2005), and the rates of non- or delayed registration among their children are very high according to our reviews on the staff from PS departments. With economic development, the number of migrant workers will increase, and the problem of BR of their children will become increasingly serious, as long as the prohibition against registration at transient residence is maintained. Some adopted children cannot obtain BR until they are teenagers or adults because of the strict and complex procedures involved in applying for documentation of adoption. Although the BR situation of out-of-plan children is improving due to a transformation in policies and their implementation by the PFP department, and a decrease in numbers of out-of-plan children, the influence of the Family Planning policies still exists, and is unlikely to be completely eliminated.

The consequences

Delayed BR will interfere with administration and long-term planning by national and local governments. Most importantly, it will prevent children from being protected under the law, and enjoying their rights to social welfare, health care and education. In China, delayed BR has the following negative effects on children. First, without BR, children cannot obtain nationality and citizenship, be independent as individuals, and receive protection by the state and its laws. Second, without BR, rural children may not obtain contracted farmland or share-site with their families to build a house, or obtain benefits from some poverty-alleviation programs, while some urban children whose family’s income is lower than the stated poverty level may not receive a cost-of-living subsidy. Third, without BR, children cannot easily enter school or may be asked to pay extra fees to enter school, and they cannot obtain medical insurance and other social insurances. Fourth, it may be difficult for children to enjoy some rights when they become adults, such as the right of employment, enrollment in the army, and marriage. In China, unregistered children are called ‘black-listed children’, and this discriminatory designation and the differences in rights from those enjoyed by registered children can have a negative influence on the children’s emotional development.

ANALYSIS OF THE BARRIERS TO BR

The serious deficiencies in the BR situation in China are a result of interactions among various influences from administrative departments, communities, families and parents. Especially, the multiple stakeholders engendered by the multiple departments pose many barriers to BR. However, the most important influence on BR is the ignorance of policy-makers, relevant staff members and the general population about its significance.

Administrative Departments

Policy-making departments

Few national and provincial policy-makers realize the significance of BR for children. They also lack a culture that can produce relevant policies that would protect children’s rights and interests. It is therefore inevitable that there are many barriers to BR caused by existing regulations and policies.

Imperfect laws and regulations concerning BR

First, the dual Hukou system and its correlation with many other aspects of life make living conditions of urban people superior to those of rural people, including access to education, employment, and social insurance and welfare (Guo and Liu, 1990; Yuan and You, 2002). As a result there is less emphasis on rural Hukou, and the BR rate in rural areas is much lower than in urban areas. Second, the regulation that children should be registered within one month after birth does not suit the conditions in China and conflicts with other rules, thus acting against BR. For example, in many rural areas it is traditional that farmers not register their babies within 100 days after birth. For people in remote mountainous areas, it is impossible to apply for BC, MBC and Hukou for their children at different departments within one month after birth. The administrative regulations for the floating population are unreasonable because most migrant workers and their families are away from their natal towns and rarely return to their hometowns, so the requirement that migrant workers return to their hometown to register their children greatly hinders their children’s BR.

Interference from family planning policies

Family Planning Policies have greatly affected BR of out-of-plan children, and caused unnecessary difficulties for BR of other children from the late 1970s to the 1990s. In recent years, the effect of family planning policies has greatly diminished, but it still exists. For example, under the central government’s pressure, some provinces have canceled the requirement for a BC when registering a baby’s birth, but still demand that PS departments report the registration information of out-of-plan children to PFP departments, while in some districts, documentation from PFP departments is still necessary for BR.

Provisions of Adoption Laws

Adopted children cannot be registered unless the adopting parents obtain adoption documents from the department of Civil Affairs. But the laws and rules concerning adopting a child are very strict and the procedure is very complicated, including getting permission from the Family Planning department. Adopting parents cannot receive the adoption documents from the department of Civil Affairs unless they have all relevant certificates; as a result a large number of adopted children are not registered.

Administrative and operational departments

The PS departments

PS departments implement registration policies with insufficient force and they lack work performance standards, incentives, and a penalty oriented system. In addition, the Hukou registry offices are located only in towns and the registrars seldom provide services to villages. Also, the importance of BR is not sufficiently advertized.

The PFP departments

The delivery and administration of BCs by PFP departments are extremely strict, which has negative effects on BR. Furthermore, some local governments and PFP departments may conceal the actual number of births or fail to register out-of-plan children in order to meet family planning goals.

The PH departments

Since they lack awareness of the importance of MBCs, PH departments have the same deficiencies as PS departments in administration and operation. Furthermore, some local Medical Care Institutions for Women and Children monopolize the delivery of MBC and add procedures to the MBC application for their own administrative benefit. Some local departments even increase the charge or add other charges to MBC, thereby hindering the delivery of MBCs and BR.

Coordination among the three registry departments

Without a goal for BR that is common to the different departments, and with the central government’s lack of force in resolving conflicts among the departments, it is easy for more powerful departments to interfere with BR for their own benefit.

In sum, multiple registration departments and multiple registration procedures, weak coordination among registry departments, inefficiency of the registration system, and lack of service orientation set up major barriers to BR.

Other relevant departments

Ignorance of the importance of BR, together with limited development of local economies, entails that local governments and other relevant departments devote insufficient manpower and material resources to BR. The result is a paucity of resources allocated to registry departments and a shortage of benefits and welfare connected with BR, with the result that the general population has little interest in BR.

Communities and Families

Community

Traditional culture

Chinese traditional culture has a significant influence on BR. For example, the norm of ‘father is son’s lord’ entails that most parents in China consider a child as their private property and undervalue their child’s independence. In emphasizing their own benefits over that of their child, the child’s rights to BR may be neglected. In much of China, people prefer sons, and some parents, under the stress of family planning policies, reserve registration for sons, leaving their daughters, who may have been born earlier, unregistered. In addition, some single mothers would rather keep their children secret for fear of public disapproval. Finally, some minorities and populations with special customs communicate little with the majority of Chinese society and do not register any of their children.

Geographic location

People who live in remote mountain areas with inconvenient transportation cannot reach a town to register their children in a timely manner.

Family

Parents’ awareness

Many rural parents do not place much emphasis on BR since they think the daily life of their young child is not affected greatly by not having Hukou. Today there is little relationship between Hukou registration, land allotment and compulsory education. Also in some undeveloped rural areas, there is a small number of inter-district migrant workers, so Hukou registration and Identity Cards are not widely used. Further, the social security system in rural areas is not sound, and there are few welfare measures connected with Hukou registration, and these greatly reduce the usage of Hukou. As a result, some rural parents do not register their children until census time or when the Hukouis needed for some special situation, such as when the children enter school. Even in urban areas, as Hukou registration exerts little influence on children’s lives before they enter nursery school, the BR rate within one month after birth is not high. In other words, parent’s awareness has a very important influence on rates of BR.

Family economy

Some poor families are reluctant to make the necessary expenditure to register their children, primarily because these families do not realize the importance of BR to their children.

PROMOTION STRATEGIES AND POLICIES

In order to promote BR, many different measures should be taken, with special focus on the rural population.

Advocacy

Effective advocacy and advertising could improve the awareness of government agencies and citizens about BR, which could, as a result, become a positive feature of BR. This would then establish the foundation for governmental progress in improving legislation, policies, administration and implementation, as well as in increasing the enthusiasm of citizens for BR. For example, the significance of BR and relevant rules at national and regional levels could be publicized through TV, radio, internet, newspapers, and other media tools; training concerning the importance of BR could be organized for decision-makers, officials at different levels, registries, and leaders of communities; workshops and seminars on BR could be held and support networks established with staff from government, media, NGOs, international organizations, and academia, as well as children, so as to raise awareness of the importance of BR for all people; children’s activities could be organized, such as knowledge competitions and performances about BR.

Legal and policy reform

The need to enact specific laws and regulations concerning BR is urgent, especially for marginalized children, such as the children of migrant workers, adopted children, and out-of-plan children. Furthermore, in order to encourage rural people to actively participate in BR, the rural Hukou system should be abandoned and unreasonable measures that are attached to the Hukou system should be removed, so that the differences in identity and rights between rural and urban people can be eliminated. Such actions should stimulate enthusiasm among rural parents to register their children’ births. Next, BR procedures need to be simplified and some of the unreasonable requirements and deadlines should be modified. For example, in the remote countryside and for migrant workers’ children, the deadline for registration should be extended in order to reduce the influence on BR of penalties for delayed BR.

Improving administration

BR should be administrated by one department rather than the current three. Alternatively, it is necessary for registry departments to strengthen coordination, establish common goals, share information and other resources, avoid conflicts of interests among departments, as well as to improve administrative and supervising systems.

Enhancing the capability building of registry departments

In order to provide service to every child and protect its rights, the capabilities of registry departments need to be improved: manpower and materials invested in BR should be increased, registrars trained, registry offices located in a geographically reasonable way, and mobile registry offices established to provide regular BR service to villages. In particularly, more attention should be paid to children in remote mountain areas and other marginalized children.

Combining BR service with other service programs properly

Combining BR service with schooling and basic health care services will greatly encourage BR in rural areas, since many unregistered children in rural areas enroll in school and participate in such health care services as vaccination. For example, BR providers should cooperate with education and health departments to identify the children without BR when they enroll in school and participate in health care services, and then to educate them and their families about BR and provide BR service to them directly.

Increasing BR interest-oriented measures

Combining BR with welfare measures and other special state-run support programs, such as Rural Cooperative Medical Services and New Rural Development, will increase the use of Hukou and hence develop parents’ enthusiasm to register their children.

Encouraging children’s participation

Children’s participation in obtaining their qualified BR will make other stakeholders exert their responsibilities and focus on the benefits to children; respect for and protection of children by government and civil society will then be enhanced.

The present paper only begins to explore BR in China and there remain many questions that demand further study. First, our estimation of BR level in China has not been totally rigorous; it is necessary to make more thorough estimates for different provinces, periods and genders. Second, data from only a few provinces are reported here and they may not be representative of the whole country. In addition, our analysis of influences on BR does not take all possible factors into account. Finally, it is necessary to carry out further study at the micro level in order to understand better the psychological factors that influence BR, which will produce a foundation for public policy analysis and intervention.

Footnotes

This work is jointly supported by the Plan International (China), the 2nd period of the National 985 Project of the Ministry of Education and Treasury Department of China (07200701) and the Changjiang Scholar Program of the Ministry of Education of China.

In China, a law is established by the National People’s Congress or the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. A regulation could be national and/or local; a national regulation is established by the State Council, while a local regulation is established by the People’s Congress or the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress of a province or of an autonomous region; rules also could be national or local; a national rule is set up by a sub-department of the State Council, while a local government rule is set up by the Municipal People’s Government of a province.

Contributor Information

Shuzhuo Li, Email: shzhli@mail.xjtu.edu.cn, shuzhuo@yahoo.com, Institute for Population and Development Studies, School of Public Policy and Administration, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, 710049, China, Tel/Fax: +86-29-8266-5032.

Yexia Zhang, School of Management, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, 710049, China.

Marcus W. Feldman, Morrison Institute for Population and Resource Studies, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA

References

- Chen X. Qualitative Research in Social Sciences. Education and Science Publishing House; Beijing: 2000. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Deen T. Rights: 50 Million Children Unregistered at Birth, Says UNICEF. Global Information Network; New York: 2002. Jun 4, [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Liu C. The Unbalance China. Hebei People’s Publishing House; Shijiazhuang: 1990. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. On the Fulfillment of Babies’ Settlement Policy. Journal of Fujian College. 1999;5:71–72. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Li Z, Li J. Study on the International Legislation of the Rights Protection of the Disadvantage Groups. Present-day Law Science. 2004;4:8–22. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Li SQ, Jiang, Sun F. Analysis and Adjustment of China’s Population Size and Structure in China’s 2000 Census. Population Journal. 2006;5:3–8. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. [Accessed on 15, June. 2006];The Child’s Right to Birth Registration-International and Chinese Perspectives. 2004 http://www.humanrights.uio.no/forskning/publ/publikasionsliste.html.

- Li X, Zhu Y. The Latest Work on Children’s Rights – on International Laws Protection of Children’s Rights. Present-day Law Science. 2005;1:116–120. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. Reformation of Household System and Harmonious Development of Rural-urban Relation. Journal of Xuehai. 2001;6:57–61. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. Population in the Fifty Years of New China. China Population Press; Beijing: 2004. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Ma F. Doctor’s Dissertation. The Institute of Graduate of Chinese Academy of Social Science; 2000. The Evolution of Household System of Present China. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- PLAN. Universal Birth Registration-a Universal responsibility. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Birth Registration – Right from the Start. Innocent Digest. 2002 MarchNo. 9 [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. The ‘Rights’ Start to Life: A Statistical Analysis of Birth Registration. Office of Strategic Information Management; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. Master’s Dissertation. Chinese Central Communist University; 2002. The Historical Review on the Form and Evolution of Household System of New China. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Study on Household System of China. Chinese Public Security University Publishing House; 2001. (In Chinese.) www.chinanews.cn/news/2004/2005-01-06/772.shtml. [Google Scholar]; News Report. 2005. China’s floating population exceeded 10% of total. [Google Scholar]

- Xu XL. Problems in Chinese Children Rights Protection: The Game Between Children Rights Realizations and Parents Benefits Choices. Journal of Yibin University. 2008;4:82–84. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- Youth Advocate Program International. Statistics Children-Youth Who Are Without Citizenship. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan N, You H. On the Drawbacks of China’s Household System and Countermeasures. Journal of Guangdong Institute of Public Administration. 2002;6:38–41. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]