Summary

Although we often encounter circumstances with which we have no prior experience, we rapidly learn how to behave in these novel situations. Such adaptive behavior relies on abstract behavioral rules that are generalizable, rather than concrete rules mapping specific cues to specific responses. Though the frontal cortex is known to support concrete rule learning, less well understood are the neural mechanisms supporting the acquisition of abstract rules. Here we use a novel reinforcement learning paradigm to demonstrate that more anterior regions along the rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex support rule learning at higher levels of abstraction. Moreover, these results indicate that when humans confront new rule learning problems, this rostro-caudal division of labor supports the search for relationships between context and action at multiple levels of abstraction simultaneously.

Rapid adaptation to novel circumstances is a hallmark of intelligent behavior. This ability partially requires the representation of rules that can associate a context with a specific behavioral response. However, adaptive behavior further requires the ability to generalize rules to novel circumstances. For example, we can rapidly work out an unusual mechanism by which a door is opened, such as pulling a cord rather than turning a knob, even if we have no prior experience using that mechanism to open a door. Such rule generalization depends on the discovery of abstract relationships between context and classes of action that are not dependent on a one-to-one mapping between a stimulus and a particular motor response.

Lateral frontal cortex, and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in particular, has an established role in representing rules for action and supporting adaptive behavior (Badre and Wagner, 2004; Bunge, 2004; D'Esposito et al., 1995; Duncan, 2001; Miller and Cohen, 2001; Passingham, 1993; Petrides, 2005; Stuss and Benson, 1987; Wallis et al., 2001). Current models of PFC conceptualize this function in terms of cognitive control, defined as the ability of frontal neurons to represent contextual information in order to bias selection of appropriate action pathways over competitors (Badre and Wagner, 2006; Botvinick et al., 2004; Braver et al., 2003; Cohen et al., 1990; Miller and Cohen, 2001; O'Reilly and Frank, 2006). Moreover, frontal cortex, in concert with striatum, is critical for the acquisition of behavioral rules (Asaad et al., 1998; Passingham, 1989; Petrides, 1987; White and Wise, 1999). However, previous studies of learning have primarily focused on the formation of concrete conditional associations between specific stimuli and responses, rather than on the learning of abstract rules.

The functional organization of frontal cortex may provide clues as to the mechanisms by which abstract rules are acquired. Growing evidence indicates that the rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex may be organized hierarchically such that neurons in more anterior regions of frontal cortex process progressively more abstract representations in the service of cognitive control (Badre, 2008; Badre and D'Esposito, 2007; Badre et al., 2009; Botvinick, 2007, 2008; Buckner, 2003; Bunge and Zelazo, 2006; Christoff and Keramatian, 2007; Koechlin and Jubault, 2006; Koechlin et al., 2003; Koechlin and Summerfield, 2007; Petrides, 2006; Race et al., 2008). In general, hierarchies facilitate learning and adapting to novel circumstances because they have the ability to represent information at multiple, increasingly abstract levels (Chase and Simon, 1973; Estes, 1972; Gick and Holyoak, 1983; Greeno and Simon, 1974; Lashley, 1951; Miller et al., 1960; Newell, 1990; Paine and Tani, 2005). Such abstracted representations are more easily analogized to novel circumstances, thereby facilitating transfer of knowledge gained in one context to a new one. Hence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the capacity for rule abstraction afforded by a putative frontal lobe hierarchy might support rapid adaptive behavior. However, previous demonstrations of hierarchically arrayed processors in the PFC have only tested the execution of well-learned rules, acquired through explicit instruction, and so these studies have not been designed to address how this functional organization might be leveraged to facilitate rule discovery. The current study seeks to fill this gap by investigating reinforcement learning of abstract versus concrete behavioral rules.

A rule can be defined as abstract to the extent that it determines a set of simpler rules based on contextual information. This type of abstraction is termed policy abstraction (Badre et al., 2009; Botvinick, 2008). For example, consider two simple rules: a circle cues a left hand response and a triangle a right hand response. This 1st-order policy specifies a one-to-one relationship between a specific stimulus (i.e., a shape) and a response. However, consider an independent set of 1st-order policy, based on size, in which a large stimulus cues a left hand response and a small stimulus a right hand response. Because the shape and size rule sets are independent, both cannot simultaneously govern responding. For instance, if the relevant set of 1st-order policy is unknown, a stimulus that is both circular and small cues opposing responses. Consequently, a more abstract rule (2nd-order policy) is required in order to specify which set of 1st-order rules (shape or size) should govern responding in the current context. For example, framing the stimulus with a red border might indicate that shape is the appropriate 1st-order policy, while green might indicate size. As this 2nd-order policy based on color specifies a class of simpler rule sets (shape or size) rather than a specific response, it is more abstract.

Using the above definition of abstraction, we designed a novel reinforcement learning task that provides participants an opportunity to acquire an abstract rule (2nd-order policy). During fMRI scanning, participants were required to learn two sets of rules, in separate epochs, that linked each of 18 different stimuli uniquely and deterministically to one of three button press responses (Figure 1). For each rule set, an individual stimulus consisted of one of three shapes, at one of three orientations, inside a box that was one of two colors for a total of 18 unique stimuli (3 shapes × 3 orientations × 2 colors; Figure 1). Participants were instructed to learn the correct response for each stimulus based on auditory feedback (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of trial events, example stimulus-to-response mappings, and policy for Hierarchical and Flat rule sets. (a) Trials began with presentation of a stimulus followed by a green fixation cross. Participants could respond with a button press at any time while the stimulus or green fixation cross was present. After a variable delay following the response, participants received auditory feedback indicating whether the response they had chosen was correct given the presented stimulus. Trials were separated by a variable null interval. (b) Example stimulus-to-response mappings for the Flat set. The arrangement of mappings for the Flat set was such that no higher-order relationship was present; thus, each rule had to be learned individually. (c) This set of many 1st-order rules can be represented as a large, Flat policy structure with only one level and eighteen alternatives. (d) Example stimulus-to-response mappings for the Hierarchical set. Response mappings are grouped such that in the presence of a red square, only shape determines the response, while in the presence of a blue square only orientation determines the response. (e) The Hierarchical set can be represented as a two-level policy structure with a 2nd-order rule selecting between the shape or orientation mapping sets, and a set of 1st-order rules then relating specific shapes or orientations to responses.

For one of the two rule sets, termed the Flat set, each of the 18 rules had to be learned individually as one-to-one mappings (1st-order policy) between a conjunction of color, shape, and orientation and a response (Figure 1B–C). In the other set, termed the Hierarchical set, stimulus display parameters and instructions were identical to the Flat set. And, indeed, the Hierarchical set could also be learned as 18 individual 1st-order rules. However, the arrangement of response mappings was such that a 2nd-order relationship could be learned instead, thereby reducing the number of 1st order rules to be learned (Figure 1D–E). Specifically, in the context of one colored box, only the shape dimension was relevant to the response, with each of the three unique shapes mapping to one of the three button responses regardless of orientation. And, conversely, in the context of the other colored box, only the orientation dimension was relevant to the response. Thus, the Hierarchical rule set permitted learning of abstract, 2nd-order rules mapping color-to-dimension along with two sets of 1st-order rules (i.e., specific shape-to-response and orientation-to-response mappings; Figure 1E).

Critically, all instructions, stimulus presentation parameters, and between-subject stimulus orderings were identical between the two rule sets. The Flat and Hierarchical rule sets only differed in that the organization of mappings in the Hierarchical set permitted learning of a 2nd-order rule. Hence, these two sets contrast a learning context in which abstract rules can be discovered with an analogous context in which no such rules can be learned. Thus, this design provides a means of studying the neural mechanisms of abstract rule learning.

Results

Behavioral Results

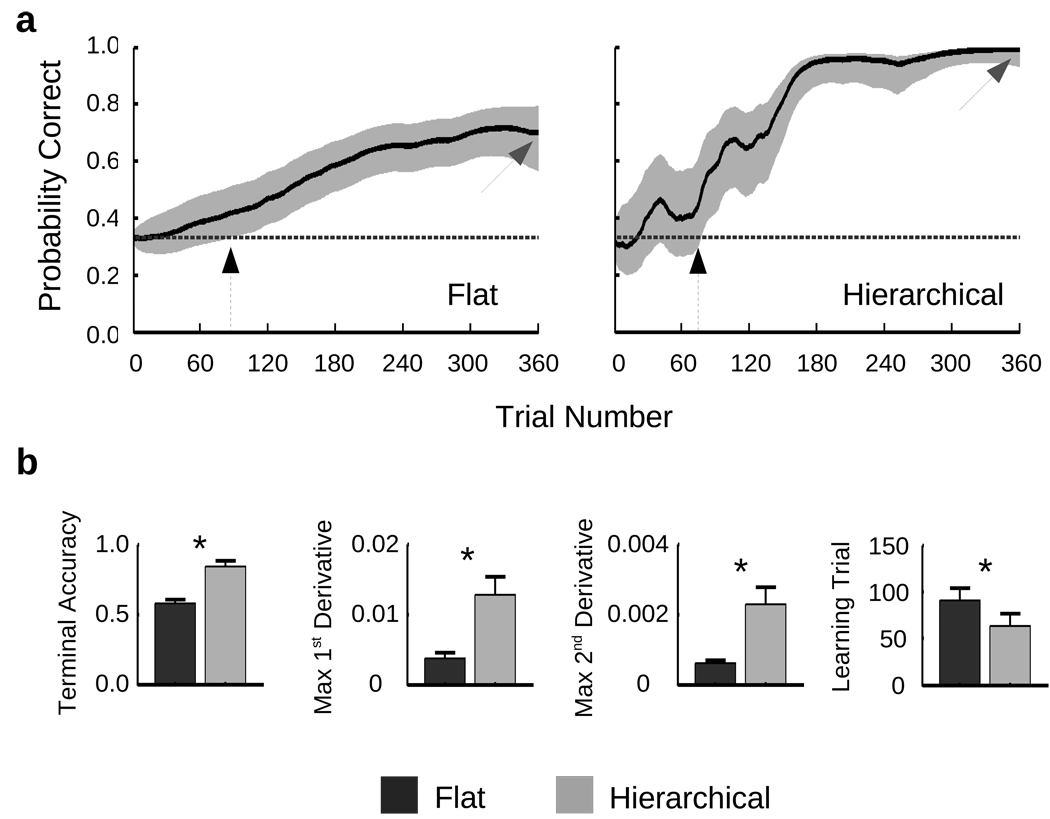

Learning curves were generated based on the estimated probability of a correct response on each trial along with a 90% confidence interval (see Methods and Figure 2A). Differences in these estimates between the Hierarchical and Flat rule sets were consistent with the acquisition of generalizable, 2nd-order rules for the Hierarchical set.

Figure 2.

Behavioral data. (a) Shown are the learning curve estimates, bounded by a 90% confidence interval, for the single subject whose learning trials for the Hierarchical and Flat sets were closest to the group means for each condition (Hierarchical = 64; Flat = 91). Black arrows illustrate the learning trial, at which the lower confidence bound rose above chance performance (33%). Gray arrows highlight the terminal accuracy. (b) Subsequent panels depict the correlates of learning ± s.e.m. across the 20 subjects for the Hierarchical and Flat sets: the terminal accuracy; the maximal first derivative of the learning curve, representing the speed of learning; the maximal second derivative of the learning curve, representing the rate of change in the speed of learning; and the learning trial (i.e. the value depicted by the black arrows in 2a). For three subjects, learning for the Flat set never rose above chance; these subjects were excluded from the calculation for the mean Flat learning trial (n = 17). (See also supplementary figure 1 for further behavioral data.)

First, generalization should make the learning task easier, in that more of the specific mappings between stimuli and responses should be acquired. Terminal accuracy was significantly higher for the Hierarchical (84%) than the Flat (58%) rule set (F(1,19)=26.3, p < .0001; Figure 2B, leftmost panel). Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of individual rules were learned in the Hierarchical (72%) than Flat (43%) set (F (1,19)=14.6, p < .005). It should be noted that neither these effects, nor any others reported here, changed as a function of which rule set was learned first.

Second, generalization should make learning more efficient, in that once an abstract rule is acquired for one stimulus, it is applicable to all others like it. Indeed, learning trial estimates – defined as the number of presentations of a specific stimulus before the response associated with that stimulus is known – came earlier for individual rules in the Hierarchical versus Flat set (t(19)=2.1, p=.05; Figure 2B, rightmost panel).

Crucially, the facilitation of learning associated with generalization should be specific to the 1st-order rules entailed by a learned 2nd-order rule. To test this prediction, we identified all 1st-order rules for each subject that were learned above chance, termed learned 1st-order rules. We then assumed that a subject knew a 2nd-order rule associating a color with either shape or orientation if, in the Hierarchical case, all 9 rules sharing that color were learned 1st order rules. We defined such sets as “known 2nd-order sets”. We note there was never a case in which all nine rules associated with a given color were known by the end of learning for the Flat rule set. The average learning trial for learned 1st-order rules that were members of “known 2nd-order sets” in the Hierarchical condition was reliably earlier in learning than the average learning trial for learned 1st-order rules in the Flat condition (t(19)=3.8, p < .005). Importantly, this effect was not driven by the fact that Hierarchical rules were learned faster, on average, than were Flat rules. Within the Hierarchical condition itself, the average learning trial for 1st-order rules that were members of “known 2nd order sets” was also reliably earlier than the learning trial for learned 1st-order rules that were not members of a known 2nd-order set (t(19)=2.5, p < .05). Moreover, there was no reliable difference in the learning trial for learned 1st-order rules in the Flat set and learned 1st-order rules in the Hierarchical set that were not members of a known 2nd-order set (t(19)=1.5, p=.2). Thus, consistent with generalization, the faster learning rate for the Hierarchical set was specific to those learned 1st-order rules in the Hierarchical set for which the 2nd order rule had been acquired.

Third, once acquired, the generalization of a 2nd-order rule to unknown 1st-order rules should be reflected in an abrupt gain in accuracy. Across subjects, Hierarchical curves consistently showed step-wise increases, presumably reflecting acquisition and generalization of a 2nd-order rule (e.g., Fig. 2A; see also Supplementary Figure 1a). By contrast, a gradual increase was evident for the Flat curves. This qualitative difference in the shape of the learning curves was reflected in a greater maximum 1st derivative (maximum learning rate) and 2nd derivative (maximum rate of change in the learning rate) for the Hierarchical than Flat rule sets (Fs > 9.0, ps < .01; Figure 2B).

We further tested the tendency for the Hierarchical learning curves to be step-wise relative to the Flat learning curves by explicitly fitting a sigmoid function to each participant’s learning curves. The sigmoid is defined by two parameters, 〈 and ®, that represent the slope and offset of the sigmoid, respectively. A larger value of 〈 indicates a steeper step, and a smaller value of ® indicates that the step occurred earlier in learning. Critically, 〈 was significantly larger (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test: Z = 2.5, p < .05) and ® was significantly smaller (Z = −2.9, p < .005) for the Hierarchical than Flat curves. Goodness-of-fit did not differ (Z = −0.75, p=.46). To ensure that these differences were not driven by model assumptions that produced the parametric learning curve estimates, we also fit sigmoid functions, via Bernoulli assumptions, directly to each subject’s responses. Consistent with the above analysis, 〈 was again significantly larger (Z = 2.7, p < .01) and ® was significantly smaller (Z = −2.7, p < .01) for the Hierarchical than Flat curves.

FMRI activation during the learning task

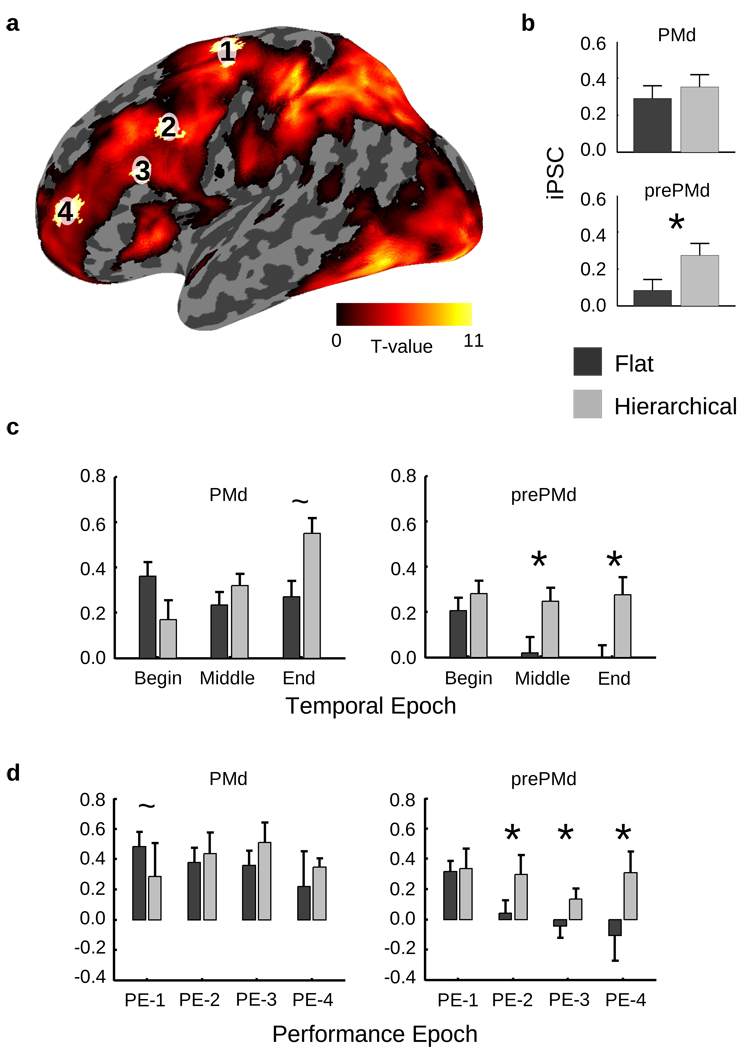

A whole-brain, voxel-wise contrast of all conditions versus baseline identified regions that were reliably activated relative to baseline during the learning task (Figure 3A). This contrast yielded a characteristic fronto-parietal and subcortical network consistent with both prior studies of rule learning and studies of hierarchical cognitive control. Bilateral bands of activation extended rostral to caudal in frontal cortex, including dorsal premotor cortex (PMd; −42 −4 60; 34 −2 56; ~BA 6), dorsal anterior premotor cortex (prePMd; −46 4 32; 54 14 30; ~BA 6/44), mid-dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (mid-DLPFC; −50 28 36; 48 34 40; ~BA 9/46), and frontal polar cortex (FPC; −34 56 10; 40 60 14; ~BA 10/46). These rostro-caudal frontal activations corresponded closely to regions previously associated with progressively abstract levels of policy selection (Badre and D'Esposito, 2007). Additional frontal activations were observed in supplementary motor area (SMA; −6 26 42; 2 24 48) and anterior insula (−32 26 −2; 28 28 −2).

Figure 3.

Basic imaging results. (a) Inflated representation of the left hemisphere showing areas that demonstrated a positive main effect of task (T-values indicated by the color bar), thresholded by a false discovery rate < 0.05. The locations of regions of interest (ROIs) determined independently from a previous dataset (Badre & D’Esposito, 2007) are overlaid (from posterior to anterior, 1 = dorsal premotor cortex (PMd), 2 = pre-premotor cortex (prePMd), 3 = mid dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (mid-DLPFC), and 4 = rostro-polar cortex (RPC)). (b) For prePMd but not for PMd, total activity as measured by the integrated percent signal changes (iPSC) for correct trials only differed across learning for the Hierarchical and Flat sets (*: p < 0.05). (c) Dividing the learning curve into three temporal epochs of 120 trials each (Begin, Middle, and End) reveals that these differences in PMd emerged after the initial phase of learning for the Hierarchical set (*: p < 0.05; ~: p < 0.10). (d) Dividing the learning curve by estimated performance (see text) confirms the temporal differences seen in prePMd. (See also supplementary figure 2).

Beyond frontal cortex, task-related activation was evident in bilateral superior (−27 −52 57; 24 −56 55) and inferior parietal lobules (IPL; −46 −40 56; 46 −36 50). Subcortically, task-related activation was observed in bilateral striatum, including the body of the caudate (−18 −6 21; 19 −6 22) and anterior putamen (−25 2 −4; 22 12 2).

To test our predictions regarding learning at different levels of abstraction and their relationship to the rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex, we defined regions of interest (ROI) in PMd (−30 −10 68), prePMd (−38 10 34), mid-DLPFC (−50 26 24), and FPC (−36 50 6) using coordinates that were previously identified in associated with parametric increases in 1st through 4th order control, respectively (Badre and D’Esposito, 2007). Analysis of the effects of learning manipulations focused initially on these ROIs.

Hierarchical versus Flat rule sets in frontal cortex

We assessed differences in frontal cortex due to the rule set, restricting this and all subsequent analyses to stimulus-related activity (i.e. prior to feedback) for correct trials only. Both the Flat and Hierarchical rule sets involve the learning and execution of simple stimulus-response mappings (1st-order policy). However, only the Hierarchical rule set includes rules at a 2nd order of policy abstraction. In prior work (Badre and D'Esposito, 2007), we demonstrated that tasks requiring only 1st-order policy activated PMd, whereas 2nd-order policy additionally engaged the more rostral prePMd. Consistent with this previous study, differences between Flat and Hierarchical rule sets were evident in prePMd (F(1,19)=5.0, p < .05), but not in the more caudal PMd region (F = .4; Figure 3B). Even more rostral mid-DLPFC and FPC, at the highest levels of abstraction, did not show a reliable difference between the Hierarchical and Flat sets (Fs < .9). Hence, despite the fact that subjects engaged in a task in which no explicit instructions were provided about a 2nd-order rule, prePMd was the only region to reliably distinguish between Hierarchical and Flat rule sets.

Time-dependent analysis of learning in frontal cortex

The overall difference in prePMd activation between Hierarchical versus Flat conditions is consistent with previous work demonstrating a hierarchical organization along the rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex (Koechlen et al., 2003; Badre and D’Esposito, 2007), though here the higher order rules were acquired through reinforcement rather than explicit instruction. However, because the present study is primarily concerned with understanding the mechanisms of abstract rule learning, determining at what point in time and in what way this difference in prePMd emerges during learning is of central importance. In particular, if the discovery and execution of 2nd-order rules only occurs after 1st-order rules are successfully learned, one might predict that activation in prePMd would remain at baseline until late in learning, and increase only in the Hierarchical condition after sufficient numbers of 1st-order rules have been acquired. Alternatively, if the search for higher order rules occurs in parallel with the search for 1st order rules, one would anticipate that activation in prePMd would be above baseline for both the Hierarchical and Flat sets from the outset of learning, remaining at that level throughout the block in the Hierarchical condition but declining to baseline by the end of learning in the Flat condition.

In order to test these predictions, learning sets were divided into three phases: Beginning, Middle, and End. The crossing of learning set (Hierachical/Flat) with learning phase (Beginning/Middle/End) was assessed in the PMd and prePMd. During the Beginning phase of learning, both regions were reliably active relative to baseline (t(19)>3.9, ps < .001), and no difference was evident between the learning sets in either region (Fs < 1.9; Figure 3C). However, by the Middle phase of learning, a reliable difference emerged between the Flat and Hierarchical sets in prePMd (F(1,19)=4.2, p < .05) but not in PMd (F = .5). The End phase again showed a reliable difference between Flat and Hierarchical in prePMd (F(1,19)=6.4, p < .05). This difference between Flat and Hierarchical in prePMd was due to a reliable decline in activation for the Flat (F(1,19) = 4.3, p < .05) rule set at the Middle and End phases of learning, whereas no such decline was evident for the Hierarchical learning set (F = .05). During the End phase, PMd also revealed a trend difference between Hierarchical and Flat rule sets (F(1,18)=3.8, p = .06). However, this difference was due to a reliable increase in activation for the Hierarchical (F(1,18)=4.9, p < .05), but not Flat (F = .8) learning set. To summarize: (1) At the beginning of learning, prePMd and PMd were active above baseline for both the Hierarchical and Flat sets. (2) By the Middle phase of learning, activation had declined reliably for the Flat but not the Hierarchical set in prePMd. (3) At the end of learning, there was a reliable increase in activity for the Hierarchical but not Flat set in PMd.

These results are initially consistent with the hypothesis that the search for rules occurs at multiple levels of abstraction from the outset of learning. However, though the region by phase interaction was reliable (F(2,36)=3.4, p < .05), individual differences in the learning curves (see Supplementary Figure 1a) could introduce variability and so reduce our sensitivity to regional differences. Additionally, due to superior accuracy in the Hierarchical set, processes related to improved performance, but unrelated to policy abstraction, could diminish the interpretability of our effects. To address these issues, learning analysis was performed on performance-aligned curves.

Performance-equated changes in learning in frontal cortex

To evaluate differences in performance between subjects, we divided the learning curves into performance epochs based on accuracy, rather than temporal epochs, using three anchor points: (1) the division between the lowest level of accuracy (PE-1) and the next highest (PE-2) was defined by the median across-subject accuracy (0.42) at the learning trial; (2) the division between the highest level of accuracy (PE-4) and the next lowest (PE-3) was defined by the median terminal accuracy (0.70); and (3) the division between performance levels two and three (PE-2 and PE-3) was defined as one-third of the difference in accuracy between the two extreme anchor points (0.51). Using this approach, accuracies were equated for the first three bins (ts < 1.2, ps >0.12). Because many fewer subjects reached the highest level of accuracy in the Flat (5) as compared to the Hierarchical (15) condition, accuracies were necessarily different for PE-4 (Supplementary Figure 1b). Consequently, PE-4 was not included in the statistical analyses.

Consistent with the results of the time-based analysis, activity in prefrontal cortex strongly differentiated the Hierarchical and Flat conditions (Figure 3D). A repeated-measures ANOVA inclusive of PMd and prePMd demonstrated both ROI × learning set (F(1,19) = 12.4, p = 0.002) and ROI × performance epoch (F(2,38) = 12.6, p = 0.0001) interactions. These differences were confirmed by direct post-hoc comparison of Hierarchical and Flat activity in prePMd, which was significant for PE-2 and PE-3 (ts > 1.8, ps < 0.05) but not for PE-1 (t(32) = −0.5, p = 0.33). By contrast, activation in the more caudal PMd did not reliably differ between learning sets for any performance epoch (ts < 1.5). Thus, results from the performance based analysis corroborated those from the time-based analysis: Hierarchical versus Flat differences in prePMd emerged late in learning due to a decline in activation for the Flat relative to the Hierarchical rule set.

Correlation of activation in prePMd and behavior during hierarchical learning

Does the activation early in learning for both Flat and Hierarchical sets relate to successful higher order rule learning? The previous two hypotheses make opposite predictions concerning the locus of such a relationship. If 1st-order rules must first be learned in order for 2nd-order rules to be acquired, early activity in areas supporting 1st-order rule acquisition (PMd) should be predictive of subsequent 2nd-order rule learning. Conversely, if 1st-order and 2nd-order rules are explored in parallel, early activity in areas supporting 2nd-order rule learning (prePMd), but not 1st-order rule learning (PMd), should be predictive of successful 2nd-order rule acquisition. In order to address this question, we conducted between-subjects correlations of the mean activation at the Beginning phase of learning, across Hierarchical and Flat sets, with the behavioral differences between Hierarchical and Flat learning sets (i.e., learning trial, terminal accuracy, max 1st, and max 2nd derivatives) that mark the successful acquisition of the higher order rules. As depicted in Figure 4, Beginning phase activation in prePMd correlated reliably with the difference in learning trial (R = .51; t(16)=2.3, p < .05), terminal accuracy (R = .56; t(19)=2.9, p < .05), and max 1st derivative (R = .51; t(19)=2.5, p < .05). A positive trend was also evident for the fourth marker, the max 2nd derivative (R=.39; t(19)=1.8, p = .09). However, no such correlations were significant for PMd (Rs < .3, ps >.21). Thus, these data provide evidence that early activation in prePMd and not PMd reflects search for higher order rules.

Figure 4.

Scatter plots demonstrating brain-behavior correlations. The x-axis of each plot shows the integrated percent signal change (iPSC) for correct trials only versus baseline for the beginning phase of learning collapsed across rule set (Hierarchical/Flat) and accuracy (correct/error) for PMd (left plots) and prePMd (right plots). This early learning activation across rule sets is plotted against the difference in learning trial (row 1), terminal accuracy (row 2), max 1st derivative (3rd row), and max 2nd derivative (row 4) between Hierarchical and Flat rule sets.

Time- and performance-dependent analysis of learning in striatum

Consistent with past work on reinforcement learning (Cohen and Frank, 2009; Cools et al., 2002; Dayan and Balleine, 2002; Frank and Claus, 2006; Hadj-Bouziane et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2000; Packard and Knowlton, 2002; Schonberg et al., 2007; Seger, 2008; Sutton and Barto, 1998; Toni et al., 1998; Tremblay et al., 1998), the whole-brain analysis reliably identified regions in the striatum – both caudate and anterior putamen – that were active during learning relative to baseline (Figure 5). Unlike PMd and prePMd, stimulus-related activity (prior to feedback) in striatum increased with learning of the Hierarchical but not Flat set, (F(1,19) = 6.9, p < 0.05) without significant interactions between conditions (Fs < 1.5, ps >0.2). Post-hoc comparison revealed a difference between rule sets by the end of learning in the left putamen (t(19) = 2.2, p < 0.05) and right caudate (t(19) = 2.4, p < 0.05), and a trend difference in the left caudate (t(19) = 1.9, p = 0.07; Figure 5A). Performance-based analysis was consistent with these effects (see Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 5.

Striatum/GC analyses. (a) Areas within the striatum demonstrating a positive main effect of task were identified in both caudate and putamen. Across time, the integrated percent signal change (iPSC) in both areas for correct trials only tended to be greater in the Hierarchical than the Flat case (*: p < 0.05; ~: p < 0.10). (b) Despite parallel striatal univariate changes, Granger causality analysis demonstrated that BOLD signal in putamen (Pt) was reliably Granger causal (*: p < 0.05; **; p < 0.0005) for activity within PMd and prePMd, which was in turn reliably Granger causal for activity in the caudate (Cd). (To PMd and prePMd from left putamen: GC = 0.016 and GC = 0.003, respectively; from right putamen: GC = 0.026 and GC = 0.007, respectively. From PMd and prePMd to left caudate: GC = 0.012 and GC = 0.013, respectively; to right caudate: GC = 0.022 and GC = 0.013, respectively). Slices show the main effect of task (T-values indicated by the color bar), with Pt and Cd regions of interest designated by the small circles at the origins/terminations of the GC arrows. See also supplementary figures 3 and 4, and supplementary table 1, for further details.

Effective connectivity analysis of the fronto-striatal network

Learning of 1st-order stimulus-response associations has been consistently shown to depend on dynamic interactions between striatum and cortex (Hadj-Bouziane et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2000; Packard and Knowlton, 2002; Seger, 2008; Toni et al., 1998; Tremblay et al., 1998). Thus, we evaluated effective connectivity between them using Granger causality (GC), a method for determining whether the BOLD time series in one region helps to predict the time series in another (Goebel et al., 2003; Kayser et al., 2009; Roebroeck et al., 2005) (see Supplement for additional analysis). PMd and prePMd were Granger causal for the bilateral caudate (ps < .0005; Figure 5B). Conversely, activity in bilateral putamen was Granger causal for both PMd and prePMd (ps < 0.05). Importantly, none of the above effects differed significantly between rule sets (ps > 0.18).

Discussion

In the present study, we contrasted learning of two rule sets in which only the Hierarchical set afforded the opportunity to learn an abstract, 2nd-order rule. Broadly, results from this experiment provide fundamental insights into the way that humans approach novel learning problems. To summarize the results: (1) Participants were capable of rapidly acquiring abstract rules when they were available. (2) Activation was evident in both PMd and prePMd early in learning but declined in the more rostral prePMd by the end of learning of the Flat set, which contained no 2nd-order rules. (3) Activation early in learning in prePMd across Hierarchical and Flat sets, but not in PMd, was correlated with behavioral differences between the Hierarchical and Flat learning curves. (4) Striatum showed greater activation by the end of learning for the Hierarchical relative to the Flat set, but the dynamics of fronto-striatal interactions did not differ between sets – i.e. for both, the putamen influenced, while caudate was influenced by, activation in PMd and prePMd. These results suggest that from the outset of learning the search for relationships between context and action may occur at multiple levels of abstraction simultaneously, and that this process differentially relies on systematically more rostral portions of frontal cortex for the discovery of more abstract relationships. However, dynamic interactions between striatum and frontal cortex that support reinforcement learning appear common across levels of abstraction.

Growing evidence suggests that the frontal cortex may possess a rostro-caudal organization whereby more rostral regions support cognitive control involving progressively more abstract representations (Badre, 2008; Badre and D'Esposito, 2007; Badre et al., 2009; Botvinick, 2007, 2008; Buckner, 2003; Bunge and Zelazo, 2006; Christoff and Keramatian, 2007; Koechlin and Jubault, 2006; Koechlin et al., 2003; Koechlin and Summerfield, 2007; Petrides, 2006; Race et al., 2008). An important question left open by these previous experiments is the extent to which this rostro-caudal organization can be leveraged to facilitate learning of abstract rules. Consistent with past work, our results demonstrate that a differentiation does indeed emerge rostrally, in prePMd, when a 2nd-order rule must be learned through reinforcement rather than explicit instruction. However, critical to understanding the mechanisms of abstract rule learning is understanding how this difference arises. In particular, there are at least two qualitatively distinct ways to account for the emergence late in learning of a difference in activation between the Hierarchical and Flat rule sets in prePMd. (1) PrePMd might be recruited to search for and execute a 2nd-order rule only after 1st-order rules have been learned. (2) PrePMd might be directly involved in the search for, as well as the execution of, 2nd-order policy from the outset of learning and decrease its involvement to the extent that such rules are not rewarded. Our data are consistent with the second of these proposals, and inconsistent with the first. Specifically, activation is evident early in prePMd, before all 1st or 2nd-order rules are known, and in the case of the Flat set even when no 2nd order rules can be known. Moreover, this early activation in prePMd, across learning conditions (i.e., Flat or Hierarchical), correlates with discovery of 2nd-order rules when they are available, indicating that this activation reflects neural processes related to the early search for abstract rules. Thus, the decline in activation in prePMd during the Flat set, when 2nd-order rules are not available, may reflect the attenuation of higher-level search when higher order rules are not rewarded.

Following from this account, this result provides potential insight into another fundamental question concerning a putative rostro-caudal hierarchical organization of the frontal cortex; namely, to the extent that the brain does possess such an architecture, what advantages might it convey over other schemes? In particular, it has been demonstrated that though complex action may be represented hierarchically (i.e., in terms of goals, subgoals, etc.), the existence of hierarchical representations does not require that the action system itself segregate these representations among spatially separate pools of neurons (Botvinick and Plaut, 2004; Botvinick, 2007). One possible advantage of having such an organization, then, is that structural hierarchies can facilitate learning of tasks that require acquisition of abstract policy relationships (Paine and Tani, 2005). One reason for such efficiency could be the capability of hierarchical structures to search independently for rules at multiple levels of abstraction (i.e. in parallel). The present results are consistent with this perspective in that frontal cortex appears to leverage its hierarchical organization in order to engage in search at multiple levels of abstraction from the outset of learning.

Interestingly, these results also provide a potential account of the classical learning/execution dissociation between PFC and PMd during rule learning. In particular, it has been widely noted that with substantial training, activity in PFC declines and activity in PMd is sustained (Brasted and Wise, 2004; di Pellegrino and Wise, 1993; Hadj-Bouziane et al., 2003; Hoshi and Tanji, 2006, 2007; Lucchetti and Bon, 2001; Mitz et al., 1991; Passingham, 1988, 1989; Petrides, 1985a, b, 1987; Boettiger and D'Esposito, 2005). And, indeed, lesioning PFC after learning does not impair subsequent execution of the rules (Bussey et al., 2001; Petrides, 1985b). In the present study, learning the Flat rule set is analogous to these past studies of rule learning, as it involves learning of arbitrary 1st-order rules. Indeed, perhaps consistent with these past experiments, activation declines over the course of learning in prePMd but not in PMd. However, during learning of the Hierarchical set, activation does not decline but is sustained in prePMd throughout learning. Thus, past distinctions between learning and execution of rules in frontal cortex may also reflect the fact that most rules in these studies are1st-order policy, by our definition, and so may not have been abstract enough to require sustained involvement of the PFC.

Finally, these results have implications for the study of changes in frontal cortex and striatum during reinforcement learning (Brasted and Wise, 2004; Fujii and Graybiel, 2005; Loh et al., 2008; Pasupathy and Miller, 2005). At least two alternative models have been proposed with respect to frontostriatal dynamics during learning. In the first, frontal cortex serves to uncover patterns in the environment that are subsequently consolidated in the basal ganglia (Graybiel, 1998). This hypothesis predicts that cortical activity should precede that of the striatum. Alternatively, the striatum may uncover stimulus-reward contingencies that merit more dedicated cortical processing (Houk and Wise, 1995). This alternative hypothesis appears to predict the reverse, namely that basal ganglia activity should precede that of the frontal cortex. These timing differences have been suggested not only to occur across the course of learning, with either cortex or basal ganglia instructing the other across this longer time scale, but also to potentially reflect (and possibly to result from) moment-by-moment precedence of activity (Houk and Wise, 1995).

Previous results in the non-human primate have supported both sides of this controversy. Pasupathy and Miller (2005) found that recordings from both area 9/46 of the prefrontal cortex and the head and body of the caudate, were consistent with the latter hypothesis in macaques performing a well-learned serial reversal task. In their study, caudate activity reliably preceded that of the PFC throughout learning, but moved relatively earlier in time as learning proceeded. However, Fujii and Graybiel (2005) found that local field potentials in prefrontal cortex peaked earlier than LFPs in striatum on single trials as macaques performed a well-learned serial saccade task (also see Brasted and Wise, 2004). Our effective connectivity results point to a potentially more complex system in which the frontal cortex both influences and is influenced by the striatum during rule learning. Moreover, we demonstrate that this temporal relationship between BOLD signal in the putamen, cortex, and caudate is consistent across the duration of learning. Such a dynamical system is broadly consistent with a range of proposals in the reinforcement learning literature that assume functional divisions both within the striatum and within cortex itself, and that acknowledge dynamic interactions between them such that the striatum can influence cortical representations – e.g. through updating/gating – and can likewise be influenced by what the cortex represents – e.g. for the purposes of learning and action selection (Alexander et al., 1986; Daw et al., 2005; Frank et al., 2004; Grahn et al., 2008, 2009; Hazy et al., 2007; Houk and Wise, 1995; O'Reilly and Frank, 2006; O'Reilly et al., 2007; Seger and Cincotta, 2005, 2006).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the rostro-caudal architecture of frontal cortex may support rapid learning of action rules at multiple levels of abstraction. When encountering a novel behavioral context, we may search for relationships between context and action at multiple levels of abstraction simultaneously, a capability that underlies our remarkable behavioral adaptability and our capacity to generalize our past learning to new problems. Hence, how we address novel problems in reasoning, decision-making, and selecting actions under uncertainty may very well reflect both the adaptability and the constraints conferred by the basic functional organization of frontal cortex.

Experimental Procedures

Participants

Twenty right-handed, native English speakers (8 female; ages 18–31 yrs) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision were enrolled in the study. Data from an additional six participants was collected but excluded due to excessive head motion (> 3mm: 4 subjects) or an inability to learn above chance in either condition (2 subjects). All participants underwent prescreening for neurological or psychological disorders, use of medications with potential vascular or CNS effects, and any contraindications for MRI. Normal color vision was verified for all subjects as assessed by the Ishihara test for color deficiency. Participants received a base payment of approximately $56, and an average bonus of $20.57 for correct responses during the task (see Behavioral Procedures). Informed consent was obtained from subjects in accordance with procedures approved by the Committees for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Berkeley and University of California, San Francisco.

Logic and Design

In order to investigate the discovery of abstract rules, a reinforcement learning task was designed that required the learning of two rule sets, one of which contained a higher order rule structure (Hierarchical rule set) and one that could only be learned as one-to-one mappings between stimuli and responses (Flat rule set). Participants were not given an indication through an instruction or any other cue that a higher order structure existed in one of the rule sets. Moreover, trials for both rule sets were identical in terms of all stimulus presentation parameters, instructions, and response-reward contingencies.

Each rule set was learned over the course of 360 individual learning trials divided equally into six fMRI scan runs. Each trial commenced with the presentation of a stimulus display consisting of a nonsense object (i.e., without a real-world counterpart) appearing in one of three orientations (up [0°], left [−90°], or oblique [23°]) and bordered by a colored square. The stimulus display subtended approximately 10 degrees of visual angle. Two colors, three object shapes, and three orientations were used for each rule set, the conjunction of which resulted in 18 unique stimulus displays (i.e., 3 shapes × 3 orientations × 2 colors). Each of the 18 unique displays occurred 20 times across the six fMRI runs for a given rule set. The specific colors and shapes differed across the two rule sets within subject and were counterbalanced for rule set across subjects.

The object and square appeared together for 1 s and were then replaced by a green fixation cross that appeared for up to an additional 2 s. While the stimulus display or green fixation cross was present the participant could respond with one of three buttons using the index, middle, or ring fingers of his right hand. Once a response was made or 3 sec had passed without a response, the fixation cross became red and no further responding was allowed. If a participant had not responded by the 3 s deadline, that trial was scored as incorrect. The red fixation cross following a response or upon reaching the response deadline was presented for either 0, 1, or 2 seconds, after which feedback was provided in the form of an auditory tone. The variable interval permitted estimation of the BOLD response to feedback independent from that to the stimulus display.

A pure high tone (750 Hz) indicated a correct response, and a buzzing tone (combination of 300 and 400 Hz pure tones) indicated an incorrect response. Participants were given a $0.05 bonus reward for each correct response. A running total bonus was provided at the end of each run. Following feedback the red fixation cross remained on the screen for a variable null inter-trial interval (mean 1.5 s). The order of trials and duration of inter-trial intervals within a block was determined by optimizing the efficiency of the design matrix so as to permit estimation of the event-related response (Dale, 1999). Efficiency was equated across rule sets, and the order of rule set learning (i.e., whether Hierarchical or Flat was learned first) was counterbalanced across participants.

For both rule sets, participants were given the same instruction. No indication was given that a higher order relationship existed or that they should search for an abstract rule. Participants did not practice the task but they were allowed to fully familiarize themselves with all 18 stimuli they would encounter for a given rule set prior to conducting the learning trials for that rule set. Hence, there were no differences in any stimulus presentation parameters or instructions between the rule sets. Where the two rule sets differed was simply in the arrangement of mappings between stimulus displays and responses (Figure 1). For the Hierarchical set, the mappings between the 18 stimulus displays and 3 responses were ordered such that in the context of one colored box, shape fully determined the response. In other words, each of the three shapes corresponded to one of the three buttons regardless of the orientation of the object. Conversely, in the context of the other color, orientation fully determined the response. Thus, a 2nd-order rule, linking color and dimension, determined the relevant set of 1st-order rules that linked shape and response or orientation and response. For the Flat set, the arrangement of responses was such that no such higher order relationship existed. Thus, each of the 18 1st-order rules linking a unique stimulus display with one of the three responses had to be learned individually. Critical to the logic of the experiment, the Hierarchical set could be learned as 18 1st-order rules, if participants could not discover the higher order relationship. By contrast, the Flat structure did not afford the opportunity to acquire 2nd-order rules, and so had to be learned as a set of one-to-one mappings between stimulus and response.

In counterbalancing the specific mappings between stimulus displays and responses across subjects, two additional constraints were applied beyond those listed above. First, all responses were represented equally across the entire set. Second, as three of the specific object-orientation combinations in the Hierarchical learning set had the same response regardless of colored box (i.e., those cases in which the orientation and shape cued congruent responses), we ensured that three object-orientation combinations also shared a response across colored boxes in the Flat set, equating this feature of the rule sets.

Behavioral Analysis

Learning curves were calculated using a state-space modeling procedure (Smith et al., 2004) that estimates the probability of a correct response on each trial as a function of a latent Gaussian state process (i.e., the state of knowledge the subject) and an observable Bernoulli response process (i.e., the responses of the subject). In other words, the model uses the learner’s trial-by-trial responses (either correct or incorrect) to estimate his knowledge about the task over time. In contrast with “sliding average” or other methods of computing learning curves, this approach allows one to define a confidence interval associated with the estimate of learning on each trial. Thus, this method produces a “learning trial”, or the trial at which the confidence interval no longer encompasses chance performance. We note that because this method estimates a single value for the variance of the Gaussian state process across learning, it does not incorporate details of the task or make assumptions about hierarchical learning. Learning curves using this procedure were calculated both for the entire rule set and also for each of the 18 rules individually based on the 20 encounters with a particular stimulus display. In addition to the behavioral analyses described below, these curves were used for the fMRI analysis (see below).

Based on learning estimates calculated using this approach, we focused our behavioral analysis on four components of the curve: (1) the learning trial, as described in the preceding paragraph; (2) the terminal accuracy (i.e. the probability of a correct response on the final trial), which is related to the degree of learning at the conclusion of the session; (3) the maximal first derivative of the learning curve, which serves as an index of the maximal speed of learning over the session; and (4) the maximal second derivative of the curve, which defines the maximal rate of change in the learning rate over the session.

We further conducted a model-based analysis in order to explicitly assess the shape of the learning curves for the Hierarchical and Flat learning sets. In particular, we fit a sigmoid function defined as follows

| (Eq. 1) |

both to the learning curves, and directly to the subject’s binary responses based on Bernoulli assumptions. In this function, 〈 reflects the slope of the sigmoid and ® defines the temporal offset relative to the start of the learning session. A step-wise function will have a steep slope (large 〈), and faster learning will have a shorter offset (smaller ®). Parameters (〈 and ®) were estimated using a nonlinear least-squares data fit (the Matlab function “nlinfit”; http://www.mathworks.com). Goodness of fit was assessed using a |2 criterion:

| (Eq. 2) |

where yi represents the probability of a correct response at time i, as determined by the learning curve, and ŷi represents the sigmoid-derived estimate of this value. We did not include an additional parameter to allow for variation in asymptotic performance.

Because the rules are deterministic and occupy a finite space, there is not an a priori reason to believe that learning in the Flat case should asymptote below perfect performance, rather than simply taking longer due to the larger number of individual stimulus-response relationships that must be learned.

MRI Procedures

Whole-brain imaging was performed on a Siemens 3T TIM Trio MRI system using a standard 12-channel head coil. Functional data were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar pulse sequence (TR = 2 sec, TE = 28 ms, flip angle = 90°; 29 axial slices, matrix = 128 × 128, FOV = 230 × 230 mm, slice thickness = 3 mm, 203 volume acquisitions per run). High-resolution T1-weighted (MP-RAGE) anatomical images were collected for anatomical visualization. Head motion was restricted using firm padding that surrounded the head. Visual stimuli projected onto the screen were viewed through a mirror attached to the head coil. Auditory feedback was presented through Siemens headphones provided as a stock component with the Trio scanner. All experimental scripts were programmed and run on a Macintosh computer using the Psychophysics Toolbox in MATLAB (http://psychtoolbox.org/).

fMRI Analysis

Functional imaging data were processed using SPM2 (Wellcome Dept. of Cognitive Neurology, London). Following quality assurance procedures to assess outliers or artifacts in volume and slice-to-slice variance in the global signal, functional images were corrected for differences in slice acquisition timing by resampling all slices in time to match the first slice, followed by motion correction using sinc interpolation across all runs. The mean functional image was then coregistered with the high-resolution MP-RAGE anatomical image. After normalizing the MP-RAGE to MNI stereotaxic space, we applied the same normalization parameters (determined by a 12-parameter affine transformation along with a nonlinear transformation using cosine basis functions) to each of the realigned functional images. Images were resampled into 2 × 2 × 2 mm voxels and then spatially smoothed with an 8-mm FWHM isotropic Gaussian kernel.

Statistical models were constructed under the assumptions of the general linear model. For time-based analyses, we evaluated each of the twelve approximately 6-minute runs that comprised the experiment with a separate set of four regressors. (Out of the 20 subjects * 12 runs/subject = 240 total runs, 7 individual runs were excluded due to movement artifact.) These four regressors consisted of the onset times for correct and incorrect responses, divided by whether they represented the appearance of the stimulus or the succeeding feedback tone. Subsequent contrasts treated the first, middle, and final two runs for the Hierarchical and Flat conditions as “begin”, “middle”, and “end”, respectively. These contrasts, and all subsequent analyses, were limited to correct trials only. For performance-based analyses, each of the 12 runs could be defined by up to 8 regressors, once again representing the onset times for correct and incorrect responses but divided by whether performance was in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th performance level. As described in Results, the first performance level ranged from an accuracy of 0.0 to the median probability across subjects of a correct response at the learning trial (0.42). The fourth performance level ranged from the median terminal accuracy (0.70) to perfect accuracy. The difference between the median probability of a correct response at the learning trial, and that at the terminal accuracy, was divided again such that performance level two ranged from the medial learning trial accuracy to one-third of this difference (0.51), and performance level three covered the range occupied by the other two-thirds of this difference. As noted in Results, because many fewer subjects reached the highest level of accuracy in the Flat (5) as compared to the Hierarchical (15) condition, accuracies could not be well-matched for PE-4 (Supplementary Figure 1b), and our analyses instead focused on the other performance epochs.

Statistical effects were estimated using a subject-specific fixed-effects model, with session-specific effects and low-frequency signal components (< .01 Hz) treated as confounds. Linear contrasts were used to obtain subject-specific estimates for each effect. These estimates were entered into a second-level analysis treating subjects as a random effect, using a one-sample t-test against a contrast value of zero at each voxel. Voxel-based group effects were considered reliable to the extent that they consisted of voxels that exceeded an FDR-corrected threshold of p < .05. We note that the use of FDR here makes an assumption of independence among voxels which is likely violated (Chumbley and Friston, 2009), and consequently, though controlling the false discovery rate for voxels, this correction may not do so for regions. For the purpose of additional anatomical precision, group contrasts were also rendered on an MNI canonical brain that underwent cortical “inflation” using FreeSurfer (CorTechs Labs, Inc.) (Dale et al., 1999; Fischl et al., 1999).

Whole brain voxel-wise event-related analysis was supplemented by region-of-interest (ROI) analysis that estimated the shape of the change in BOLD response from the onset of each trial event. ROIs were defined in two ways that were independent and unbiased with respect to the tests of interest: (1) the ROIs for PMd, prePMd, IFS, and FPC were taken from Badre and D’Esposito (Badre and D'Esposito, 2007) based on their association with 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th order rule execution, respectively; (2) all other ROIs were defined as all significant voxels within 8 mm of a maximum chosen from the contrast of all conditions versus fixation baseline in the current experiment. Selective averaging with respect to peristimulus time was conducted using the Marsbars toolbox (Brett et al., 2002), permitting assessment of the signal change associated with each condition. Integrated percent signal change was computed based on the integral of the peak time point – defined neutrally at 4 seconds based on the average across conditions for time points up to 14 seconds after trial onset – plus and minus two time points, relative to an implicit baseline of zero. All ROI data were subjected to repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA). Paired t-tests were applied for all time-based post hoc analyses. For performance-based analyses, we employed a more conservative post hoc measure (a weighted, unpaired T-test) to account directly for variability in the number of trials within each performance level for each subject (Supplementary Figure 1).

In order to evaluate the influence of each of these ROIs on the others, we used bivariate Granger causality. This technique determines whether the time series in one voxel or region helps to predict upcoming time points in a second time series; if so, that voxel or region is said to be Granger causal (GC) for the second. The complexity of the underlying model that permits these computations can vary. In this case, as in our previous work, we restricted our analysis to linear models (see (Kayser et al., 2009) for full details).

To generate the relevant time series, we used each subject’s normalization parameters to project all of our ROIs into the native space. We then applied these ROIs to the relevant subject’s realigned functional images in order to define the time course for each significant voxel, within each ROI, for each of that subject’s runs. After computing the run-by-run GC values for each subject, we computed the median of each subject’s ROI-by-ROI GC value across each condition (Hierarchical versus Flat), as there were no significant differences between GC values for the first two, last two, and all six runs (data not shown). We performed Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests for each ROI-ROI pair to determine significance across subjects (see Supplement for a further description of GC analyses).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (MH63901, NS40813, and NS065046). We thank K. Sakanaka and D. Erickson for assistance with data collection. We also thank M. Brett and M. J. Frank for helpful discussions during preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaad WF, Rainer G, Miller EK. Neural activity in the primate prefrontal cortex during associative learning. Neuron. 1998;21:1399–1407. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badre D. Cognitive control, hierarchy, and the rostro-caudal organization of the frontal lobes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badre D, D'Esposito M. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for a hierarchical organization of the prefrontal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:2082–2099. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.12.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badre D, Hoffman J, Cooney JW, D'Esposito M. Hierarchical cognitive control deficits following damage to the human frontal lobe. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:515–522. doi: 10.1038/nn.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badre D, Wagner AD. Selection, integration, and conflict monitoring; assessing the nature and generality of prefrontal cognitive control mechanisms. Neuron. 2004;41:473–487. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00851-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badre D, Wagner AD. Computational and neurobiological mechanisms underlying cognitive flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7186–7191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509550103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger CA, D'Esposito M. Frontal networks for learning and executing arbitrary stimulus-response associations. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2723–2732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3697-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Plaut DC. Doing without schema hierarchies: a recurrent connectionist approach to normal and impaired routine sequential action. Psychol Rev. 2004;111:395–429. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM. Multilevel structure in behaviour and in the brain: a model of Fuster's hierarchy. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM. Hierarchical models of behavior and prefrontal function. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, Carter CS. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasted PJ, Wise SP. Comparison of learning-related neuronal activity in the dorsal premotor cortex and striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:721–740. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Reynolds JR, Donaldson DI. Neural mechanisms of transient and sustained cognitive control during task switching. Neuron. 2003;39:713–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M, Anton J-L, Valabregue R, Poline J-B. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. In 8th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain; Sendai, Japan. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic correlates of control processes in memory. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3999–4004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-03999.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA. How we use rules to select actions: a review of evidence from cognitive neuroscience. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4:564–579. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA, Zelazo PD. A brain-based account of the development of rule use in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Wise SP, Murray EA. The role of ventral and orbital prefrontal cortex in conditional visuomotor learning and strategy use in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:971–982. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase WG, Simon HA. The mind's eye in chess. In: Chase WG, editor. In Visual Information Processing. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 215–281. [Google Scholar]

- Christoff K, Keramatian K. Abstraction of mental representations: Theoretical considerations and neuroscientific evidence. In: Bunge SA, Wallis JD, editors. In Perspectives on Rule-Guided Behavior. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chumbley JR, Friston KJ. False discovery rate revisited: FDR and topological inference using Gaussian random fields. Neuroimage. 2009;44:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JD, Dunbar K, McClelland JL. On the control of automatic processes: A parallel distributed processing account of the Stroop effect. Psychological Review. 1990;97:332–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MX, Frank MJ. Neurocomputational models of basal ganglia function in learning, memory and choice. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:141–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Clark L, Owen AM, Robbins TW. Defining the neural mechanisms of probabilistic reversal learning using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4563–4567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04563.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Esposito M, Detre JA, Alsop DC, Shin RK, Atlas S, Grossman M. The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. Nature. 1995;378:279–281. doi: 10.1038/378279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Optimal experimental design for event-related fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:109–114. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:2/3<109::AID-HBM7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw ND, Niv Y, Dayan P. Uncertainty-based competition between prefrontal and dorsolateral striatal systems for behavioral control. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1704–1711. doi: 10.1038/nn1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Balleine BW. Reward, motivation, and reinforcement learning. Neuron. 2002;36:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Pellegrino G, Wise SP. Visuospatial versus visuomotor activity in the premotor and prefrontal cortex of a primate. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1227–1243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01227.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J. An adaptive coding model of neural function in prefrontal cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:820–829. doi: 10.1038/35097575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes WK. An associative basis for coding and organization in memory. In: Melton AW, Martin E, editors. Coding Processes in Human Memory. Washington, D.C: V. H. Winston & Sons; 1972. pp. 161–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9:195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Claus ED. Anatomy of a decision: striato-orbitofrontal interactions in reinforcement learning, decision making, and reversal. Psychol Rev. 2006;113:300–326. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O'Reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science. 2004;306:1940–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.1102941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Graybiel AM. Time-varying covariance of neural activities recorded in striatum and frontal cortex as monkeys perform sequential-saccade tasks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9032–9037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503541102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gick ML, Holyoak KJ. Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cognitive Psychology. 1983;15:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel R, Roebroeck A, Kim DS, Formisano E. Investigating directed cortical interactions in time-resolved fMRI data using vector autoregressive modeling and Granger causality mapping. Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;21:1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn JA, Parkinson JA, Owen AM. The cognitive functions of the caudate nucleus. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn JA, Parkinson JA, Owen AM. The role of the basal ganglia in learning and memory: neuropsychological studies. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. The basal ganglia and chunking of action repertoires. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1998;70:119–136. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeno JG, Simon HA. Processes for sequence production. Psychological Review. 1974;81:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Hadj-Bouziane F, Meunier M, Boussaoud D. Conditional visuo-motor learning in primates: a key role for the basal ganglia. J Physiol Paris. 2003;97:567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazy TE, Frank MJ, O'Reilly RC. Towards an executive without a homunculus: Computational models of the prefrontal cortex/basal ganglia system. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2055. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E, Tanji J. Differential involvement of neurons in the dorsal and ventral premotor cortex during processing of visual signals for action planning. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3596–3616. doi: 10.1152/jn.01126.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E, Tanji J. Distinctions between dorsal and ventral premotor areas: anatomical connectivity and functional properties. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houk JC, Wise SP. Distributed modular architectures linking basal ganglia, cerebellum, and cerebral cortex: their role in planning and controlling action. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:95–110. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser AS, Sun FT, D'Esposito M. A comparison of Granger causality and coherency in fMRI-based analysis of the motor system. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Jubault T. Broca's area and the hierarchical organization of human behavior. Neuron. 2006;50:963–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Ody C, Kouneiher F. The architecture of cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Science. 2003;302:1181–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1088545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Summerfield C. An information theoretical approach to prefrontal executive function. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley KS. The problem of serial order in behavior. In: Jeffress LA, editor. In Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior. New York: Wiley; 1951. pp. 112–136. [Google Scholar]

- Loh M, Pasupathy A, Miller EK, Deco G. Neurodynamics of the prefrontal cortex during conditional visuomotor associations. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:421–431. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti C, Bon L. Time-modulated neuronal activity in the premotor cortex of macaque monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 2001;141:254–260. doi: 10.1007/s002210100818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Galanter E, Pribram KH. Plans and the Structure of Behavior. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Mitz AR, Godschalk M, Wise SP. Learning-dependent neuronal activity in the premotor cortex: activity during the acquisition of conditional motor associations. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1855–1872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01855.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Bussey TJ, Wise SP. Role of prefrontal cortex in a network for arbitrary visuomotor mapping. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:114–129. doi: 10.1007/s002210000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell A. Unified Theories of Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly RC, Frank MJ. Making working memory work: a computational model of learning in the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Neural Comput. 2006;18:283–328. doi: 10.1162/089976606775093909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly RC, Frank MJ, Hazy TE, Watz B. PVLV: the primary value and learned value Pavlovian learning algorithm. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:31–49. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Knowlton BJ. Learning and memory functions of the Basal Ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:563–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine RW, Tani J. How hierarchical control self-organizes in artificial adaptive systems. Adaptive Behavior. 2005;13:211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Passingham RE. Premotor cortex and preparation for movement. Exp Brain Res. 1988;70:590–596. doi: 10.1007/BF00247607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passingham RE. Premotor cortex and the retrieval of movement. Brain Behav Evol. 1989;33:189–192. doi: 10.1159/000115927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passingham RE. The Frontal Lobes and Voluntary Action. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathy A, Miller EK. Different time courses of learning-related activity in the prefrontal cortex and striatum. Nature. 2005;433:873–876. doi: 10.1038/nature03287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. Deficits in non-spatial conditional associative learning after periarcuate lesions in the monkey. Behav Brain Res. 1985a;16:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(85)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. Deficits on conditional associative-learning tasks after frontal-and temporal-lobe lesions in man. Neuropsychologia. 1985b;23:601–614. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(85)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. Conditional learning and the primate frontal cortex. In: Perecman E, editor. In The frontal lobes revisited. New York: IRBN Press; 1987. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:781–795. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M. The rostro-caudal axis of cognitive control processing within lateral frontal cortex. In: Dehaene S, Duhamel J-R, Hauser MD, Rizzolatti G, editors. From Monkey Brain to Human Brain: A Fyssen Foundation Symposium. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2006. pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Race EA, Shanker S, Wagner AD. Neural Priming in Human Frontal Cortex: Multiple Forms of Learning Reduce Demands on the Prefrontal Executive System. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebroeck A, Formisano E, Goebel R. Mapping directed influence over the brain using Granger causality and fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;25:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg T, Daw ND, Joel D, O'Doherty JP. Reinforcement learning signals in the human striatum distinguish learners from nonlearners during reward-based decision making. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12860–12867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2496-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger CA. How do the basal ganglia contribute to categorization? Their roles in generalization, response selection, and learning via feedback. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger CA, Cincotta CM. The roles of the caudate nucleus in human classification learning. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2941–2951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3401-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger CA, Cincotta CM. Dynamics of frontal, striatal, and hippocampal systems during rule learning. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1546–1555. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Frank LM, Wirth S, Yanike M, Hu D, Kubota Y, Graybiel AM, Suzuki WA, Brown EN. Dynamic analysis of learning in behavioral experiments. J Neurosci. 2004;24:447–461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2908-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DT, Benson DF. The frontal lobes and control of cognition and memory. In: Perecman E, editor. The Frontal Lobes Revisited. New York: The IRBN Press; 1987. pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RS, Barto AG. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Toni I, Krams M, Turner R, Passingham RE. The time course of changes during motor sequence learning: a whole-brain fMRI study. Neuroimage. 1998;8:50–61. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay L, Hollerman JR, Schultz W. Modifications of reward expectation-related neuronal activity during learning in primate striatum. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:964–977. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JD, Anderson KC, Miller EK. Single neurons in prefrontal cortex encode abstract rules. Nature. 2001;411:953–956. doi: 10.1038/35082081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IM, Wise SP. Rule-dependent neuronal activity in the prefrontal cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1999;126:315–335. doi: 10.1007/s002210050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.