Abstract

The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene product is mutated in the vast majority of human colorectal cancer. APC negatively regulates the WNT pathway by aiding in the degradation of β-Catenin, the transcription factor activated downstream of WNT signaling. APC mutations result in β-Catenin stabilization and constitutive WNT pathway activation leading to aberrant cellular proliferation. APC mutations associated with colorectal cancer commonly fall in a region of the gene termed the mutation cluster region and result in expression of an N-terminal fragment of the APC protein. Biochemical and molecular studies have revealed localization of APC/Apc to different sub-cellular compartments and various proteins outside of the WNT pathway that associate with truncated APC/Apc. These observations and genotypephenotype correlations have led to the suggestion that truncated APC bears neomorphic and/or dominant-negative function that support tumor development. To investigate this possibility, we have generated a novel allele of Apc in the mouse that yields complete loss of Apc protein. Our studies reveal that whole-gene deletion of Apc results in more rapid tumor development than the ApcMin truncation. Furthermore, we found that adenomas bearing truncated Apc had increased β-catenin activity compared to tumors lacking Apc protein, which could lead to context-dependent inhibition of tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Apc truncation, Apc null, colon cancer, mouse model

Colorectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death in the Western world. Upwards of 80% of colorectal cancers have mutations in the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) gene, which is known to occur early in tumor development. Most of these APC gene alterations, found both in the germline in individuals with hereditary Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and in sporadic colon cancers, fall in a region of APC termed the mutation cluster region (MCR) and result in retained expression of an N-terminal fragment of the APC protein (Kinzler & Vogelstein, 1996). Genotype-phenotype correlations involving germline APC mutations suggest that different lengths and levels of APC expression can influence the number of polyps in the gut, the distribution of polyps, and extra-colonic manifestations of the disease (Nieuwenhuis & Vasen, 2007; Soravia et al., 1998). Specifically, patients that present clinically with attenuated FAP (AFAP) have reduced polyp counts and a later age of colon cancer development. Interestingly, germline APC mutations associated with AFAP fall 5′ and 3′ of the MCR, presumably resulting in APC truncations bearing different protein domains than in classical FAP and/or hypomorphic APC expression. These observations suggest a gain-of-function or dominant-negative role for APC truncated at the MCR. Paradoxically, patients with whole-gene APC deletions, albeit rare, have been found to present with classical FAP (Herrera et al., 1986; Sieber et al., 2002). More thorough analysis of the phenotypic consequences of different heritable APC alleles is hampered by the low frequency of FAP and AFAP as well as the existence of numerous genetic and environmental modifiers of the disease (de la Chapelle, 2004). Thus, we and others have turned to mouse models that faithfully recapitulate human disease as a tool to examine the consequences of various Apc mutations.

ApcMin was the first heritable mutant allele of Apc developed in the mouse (Su et al., 1992). ApcMin mice develop multiple intestinal neoplasias (Min) resembling human FAP. The ApcMin allele, which was discovered in an ethylnitrosourea mutagenesis screen, comprises a nonsense mutation in codon 850 of Apc and gives rise to a stable, truncated Apc protein similar to those found in human colon cancers. Since the characterization of the ApcMin mouse, additional alleles of Apc have been generated, involving truncations both 5' and 3' to the Min mutation (Colnot et al., 2004; Gaspar et al., 2009; Oshima et al., 1995; Pollard et al., 2009; Smits et al., 1999). As observed in human patients bearing mutations in APC, these alleles have yielded different phenotypic consequences relating to intestinal tumorigenesis (Fodde & Smits, 2001). The basis for these genotype-phenotype correlations remains largely unknown.

The APC/Apc gene product is a critical negative regulator of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Apc forms a complex with Axin and Gsk-3β that phosphorylates β-catenin on N-terminal residues, allowing for subsequent ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. When the ability of Apc to interact with this destruction complex is compromised, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and translocates into the nucleus where it binds to Tcf/Lef transcription factors to regulate target genes, such as c-myc and Axin2 (Clevers, 2006). Moreover, mutations in β-catenin that lead to protein stabilization are observed in human colon cancer and comparable mutations can initiate intestinal tumorigenesis in mice (Harada et al., 1999; Morin et al., 1997).

Beyond β-catenin deregulation, mutant APC has been suggested to contribute to colon tumorigenesis through other mechanisms. First, the vast majority of sporadic colon cancers in humans have mutations in APC, whereas other cancers with deregulated WNT signaling have an equal or greater proportion of mutations in β-Catenin or other WNT pathway components (Giles, 2003). This observation points to a special role for APC mutation specifically in colon cancer. Second, Apc is a relatively large protein of approximately 312 kDa and has a number of protein binding motifs. In fact, Apc has been shown to interact with a variety of proteins outside of the Wnt pathway and has been found in various sub-cellular locations (Aoki & Taketo, 2007; Fodde et al., 2001; Mccartney & Nathke, 2008). Furthermore, the majority of APC mutations result in a stable, truncated polypeptide, lacking most β-catenin and Axin binding domains, which lie in the middle portion of the protein. In these mutant proteins, the microtubule-binding domain and EB1-binding site at the C-terminus of APC are also lost, but the N-terminal armadillo repeats and oligomerization domains are retained (Nathke, 2004).

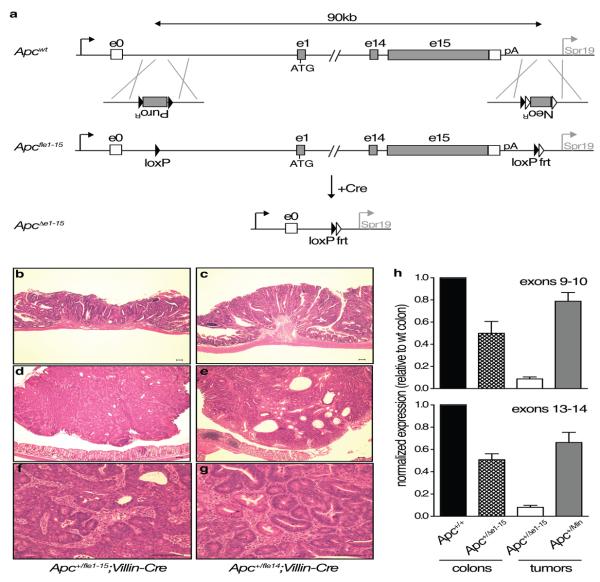

We took a genetic approach to dissect the role of truncated Apc in intestinal tumorigenesis by constructing novel, conditional and constitutive null alleles of Apc in mice. We performed sequential gene targetings in C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells, inserting LoxP sites 90 kb apart in the Apc locus flanking all 15 protein-coding exons of Apc in order to generate a Creregulatable null allele, Apcfle1−15 (Figure 1a). We then tested our allele by crossing Apcfle1−15 mice to Villin-Cre transgenic mice, which express Cre in a mosaic fashion throughout the intestinal epithelium (el Marjou et al., 2004). Apc+/fle1−15; Villin-Cre mice developed several lesions in their small intestines and colons by 4-5 months of age, whereas Apc+/fle1−15 mice without Cre never did, even when aged for greater than a year (Figure 1b,d,f; data not shown). An existing conditional Apc allele developed by Colnot et al., Apcfle14, encodes a truncated Apc protein after deletion of exon 14 by exposure to Cre recombinase activity (Colnot et al., 2004). By histological examination of tumor morphology, grade, and stromal recruitment, we found that adenomas from Apc+/fle1−15;Villin-Cre mice closely resembled those found in Apc+/fle14;Villin-Cre littermates (Figure 1b-g). These data demonstrate that conditional deletion of Apc grossly phenocopies conditional truncation of Apc.

Figure 1. Generation of Apcfle1−15 and ApcΔe1−15 alleles.

a. Schematic of the wild-type Apc genomic locus showing non-coding exon 0 and coding exons 1, 14, and 15. A floxed Puromycin resistance (PuroR) gene was targeted to intron 1 of Apc in C57BL/6 embryonic stem (ES) cells. ES cells were selected on Puromycin and screened by Southern blot for homologous recombination. Targeted clones were then transfected with a Cre expression plasmid to excise the PuroR cassette leaving behind a single loxP site. After confirming successful removal of PuroR, the intergenic region 3′ to Apc was targeted with a construct containing a Neomycin resistance gene flanked proximally by frt sites on both sides and a distal loxP site on one side (loxP-frt-NeoR-frt cassette). ES cells were selected on Neomycin and again screened by Southern blot for homologous recombination. Correctly targeted ES cells were injected into FVB blastocystes to generate chimeric mice. Chimeras were mated to wild-type C57BL/6 mice and pups were screened by coat color and PCR for germline transmission of the targeted allele. The NeoR cassette was removed in vivo by germline FlpE expression leaving a loxP and a frt site 3′ to Apc. This strategy yielded the conditional null allele Apcfle1−15. Germline expression of Cre by C57BL/6 Meox-Cre mice resulted in excision of the genomic region flanked by targeted loxP sites yielding a constitutive null allele ApcΔe1−15. ApcMin mice, to which ApcΔe1−15 mice were compared, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Both alleles were subsequently maintained by breeding to C57BL/6 mice originally from Jackson Laboratories. b-g. H&E-stained sections of small intestinal (b,c) and colonic (d-g) adenomas from Apc+/fle1−15;Villin-Cre (b,d,f) and Apc+/fle14;Villin-Cre (c,e,g) mice. Villin-Cre transgenic mice were a gift from Dr. S. Robine. Scale bar, 100μm. h. Quantitative Real-time PCR of cDNA from whole colons of 1-month-old wild-type (black bar) and Apc+/Δe1−15 (hatched bar) and colon tumors from aged Apc+/Δe1−15 (open bar) and Apc+/Min (gray bar) mice. Taqman probes (ABI) spanning exons 9 and 10 (top) and exons 14 and 15 (bottom) of Apc were used. Expression was normalized to GAPDH for each sample. Bars, mean + s.e.m. Animal studies were approved by MIT's Committee for Animal Care and conducted in compliance with Animal Welfare Act Regulations and other federal statutes relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adheres to the principles set forth in the 1996 National Research Council Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (institutional animal welfare assurance number, A-3125-01).

Next, we crossed Apc+/fle1−15 mice to Meox-Cre transgenic animals, which express Cre in the embryo, to generate a heritable null allele of Apc, ApcΔe1−15 (Tallquist & Soriano, 2000) (Figure 1a). To confirm the loss of Apc expression upon genomic deletion of the locus, we performed quantitative PCR to detect Apc message with Taqman probes spanning exons 9-10 and 13-14. Analysis of cDNA generated from whole colons of 1-month-old animals revealed the expected 50% reduction of Apc mRNA in Apc+/Δe1−15 mice compared to a wild-type littermate (Figure 1h). Apc+/Δe1−15 mice were aged to allow for spontaneous tumor formation. Histological comparison revealed no significant phenotypic difference between tumors derived from Apc+/Δe1−15 and Apc+/Min mice on a C57BL/6 background (data not shown). Individual colonic tumors isolated from aged Apc+/Δe1−15 mice showed nearly complete loss of Apc expression (Figure 1h). This expression pattern could reflect Apc promoter hypermethylation or loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) yielding tumors with ApcΔe1−15/Δe1−15 genotype, as has been described for Apc+/Min mice on C57BL/6 background (Haigis et al., 2004). Because the residual Apc expression detected is likely derived from stromal cells within the lesions, our expression analyses supports the successful generation of a null allele in mice. These data indicate that truncated Apc is not required for intestinal tumor formation and that the presence of truncated Apc does not significantly affect the tumor phenotype in the gut.

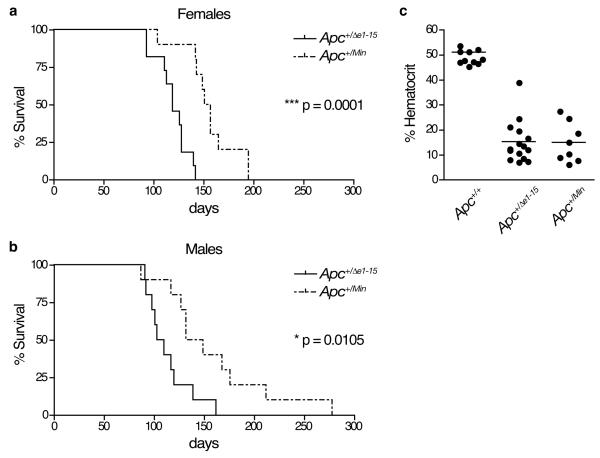

As Apc+/Δe1−15 and Apc+/Min mice were isogenic on a C57BL/6 background, we sought to compare their phenotypes more closely to determine the influence of truncated Apc on tumor development. We first examined the survival of Apc mutant cohorts by aging animals until they became moribund. Strikingly, Apc+/Min mice had a 30% increase in median survival compared to Apc+/Δe1−15 mice within both female and male subgroups (Figure 2a,b). Morbidity of aged animals was supported by reduced hematocrits, which is indicative of anemia that occurs commonly in mice with extensive intestinal tumor burdens (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Apc+/Δe1−15 mice have reduced survival compared to Apc+/Min mice.

Cohorts of mice on C57BL/6 background were progeny of Apc mutant fathers and wild-type Apc mothers. Females in survival study were kept virgin as they aged and animals were checked for moribundity on a daily basis. To reduce the influence of environmental modifiers and spontaneous mutation in our colony, cohorts were progeny of multiple parent pairs and data collection for disparate groups was performed concurrently. a. Survival curves for Apc+/Δe1−15 (solid line) and Apc+/Min (dashed line) female mice. Median survival values were 119 (n=11) and 154 (n=10) days, respectively. b. Survival curves for male mice of the same genotypes in a. Median survival values were 106.5 (n=10) and 140.5 (n=10) days, respectively. P values by chi-square statistic are indicated for each comparison. c. Percent hematocrits for wild-type and Apc mutants when moribund. Bars, mean.

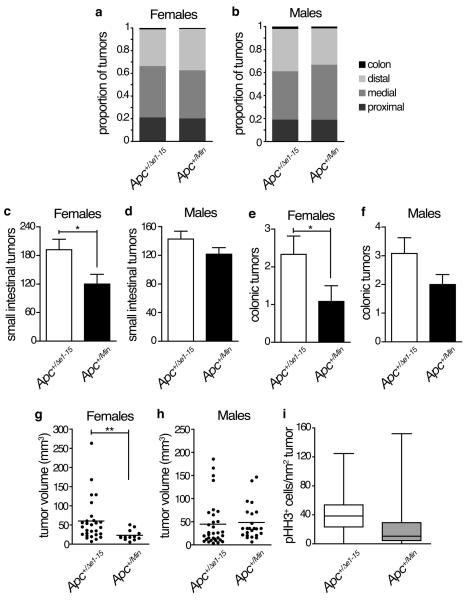

We went on to investigate the cause of reduced survival in Apc+/Δe1−15 mice. Aside from a single mouse that developed a mammary tumor, no additional extra-intestinal lesions was apparent (data not shown). Thus, the simplest explanation to account for altered survival between mutant Apc genotypes would be a difference in tumor development. We sacrificed additional cohorts of animals at 3 months of age to examine tumor distribution, multiplicity and size. The distribution of lesions through the intestinal tract did not differ between Apc+/Δe1−15 and Apc+/Min animals (Figure 3a,b). However, Apc+/Δe1−15 mice had on average more tumors compared to Apc+/Min mice (Figure 3c-f). This result was more pronounced in females where the small intestinal tumor count was increased by >60% and the colonic tumor count by >115%. In males, although the trend was apparent, the differences were not statistically significant due to variability in tumor number.

Figure 3. Apc+/Δe1−15 mice display faster tumor development compared to Apc+/Min mice.

C57BL/6 Apc mutant females (a,c,e,g) and males (b,d,f,h) were sacrificed at 3 months of age for analysis. To reduce the influence of environmental modifiers and spontaneous mutation in our colony, cohorts were progeny of multiple parent pairs and data collection for disparate groups was performed concurrently. Intestines were flushed with PBS, cut open longitudinally, and fixed flat on bibulous paper in 4 segments. Fixed intestine were stained with 1:10 dilution in water of 1% methylene blue in 95% ethanol and destained in 70% ethanol before counting tumors by dissection microscope. a,b. Distribution of tumors along intestinal tracts of Apc+/Δe1−15 (n=12 for each gender) and Apc+/Min (n=12 for each gender) mice. c-f. Total tumor counts in small intestines (c,d) and colons (e,f) of Apc mutant mice in a,b. Bars, mean + s.e.m., *p <0.05 by rank sum test. g,h. Volumes of colonic tumors from Apc+/Δe1−15 (n=28 for females and n=32 for males) and Apc+/Min (n=13 for females and n=24 for males) mice in a,b. Colonic tumor volumes were determined by plucking lesions from surface of intestine and measuring tumor masses by calipers. Volumes were calculated based on an ellipsoid shape: volume = (4/3)*pi*x*y*z, with x, y, and z being the widths of each perpendicular axis. Bars, mean, **p <0.005 by rank sum test. i. Box and whisker plots of phospho-histone H3+ cells quantified per nm2 small intestine tumor area from Apc+/Δe1−15 (open bar, n=27) and Apc+/Min (filled bar, n=13) female mice. α–β-catenin (cat#9582), α-cleaved caspase-3 (cat#9661), and α-phospho-histone H3 (cat#9701) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections as previously described (Haigis et al., 2008).

Colonic tumors were dissected from these mice and measured with calipers to determine tumor volumes. In female Apc+/Δe1−15 mice, tumors were more than twice the volume of those in Apc+/Min females (Figure 3g). There was no distinction, however, among colonic tumor volumes in males (Figure 3h). We reasoned that the difference in tumor size could be due to either increased cell death or reduced proliferation in the presence of truncated Apc. Measurement of apoptosis by cleaved-caspase 3 immunohistochemistry of adenomas revealed no apparent difference between mutant Apc genotypes (data not shown). On the other hand, upon staining for phospho-histone H3, a marker of mitotic cells, we detected consistently more positive cells in small intestinal adenomas of Apc+/Δe1−15 mice compared to those in Apc+/Min mice (Figure 3i). Thus, our data suggests that decreased survival of Apc+/Δe1−15 mice compared to Apc+/Min mice can be attributed to more rapid tumor development in the absence of truncated Apc.

Our data indicate that truncated Apc may be less efficient at promoting the early stages of intestinal tumor development than the complete loss of Apc protein. This conclusion falls at odds with the commonly-held view that truncated APC favors tumor development, which is suggested by the high prevalence of APC truncations in human colorectal cancer and by studies investigating truncated APC/Apc in model systems. However, the fact that APC truncation is frequently observed may simply be due to a higher likelihood of point/frameshift mutations occurring in APC compared to focal deletions of the locus, particularly as an early event in tumorigenesis. As mentioned above, whole-gene deletions have recently been detected in patients displaying classical FAP, indicating that truncated APC is not required for human disease (Sieber et al., 2002). This inference concurs with our findings as Apc+/Δe1−15 mice had accelerated disease, rather than an attenuated phenotype, compared to Apc+/Min mice. Furthermore, in vivo model systems used to study Apc have involved non-mammalian organisms and have focused primarily on the role of truncated Apc in organismal development. On the other hand, studies directed at addressing the role of truncated APC/Apc in tumorigenesis have mainly utilized immortalized cell lines, which undoubtedly possess secondary changes. In advanced lesions, with additional genetic/epigenetic alterations, the tumorigenic effects of truncated Apc could be different.

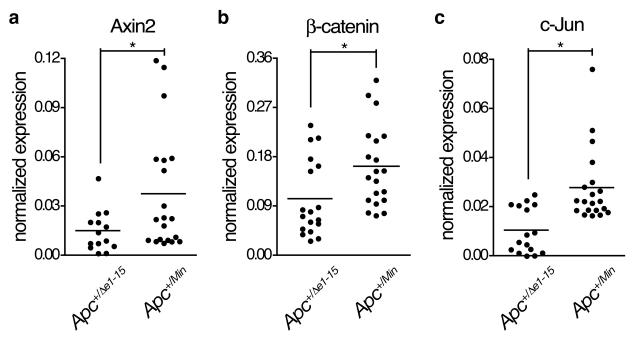

Recently, truncated APC/Apc was shown to positively regulate WNT/Wnt signaling by enhancing β-catenin stability (Takacs et al., 2008). We performed Western blot and immunohistochemistry on colon tumors from Apc+/Min and Apc+/Δe1−15 mice, but failed to observe a consistent difference in β-catenin protein levels (Supplementary Figure 1). However, increased β-catenin could be obscured by the abundance of the protein in epithelia and by already high levels of β-catenin as a consequence of Wnt pathway deregulation. Therefore, we used quantitative PCR to determine if there was evidence for increased Wnt signaling in the presence of truncated Apc. Through analysis of cDNA from Apc mutant colon tumors, we discovered that tumors from Apc+/Min mice had more than twice the expression of Axin2 than tumors from Apc+/Δe1−15 mice (Figure 4a). Although many β-catenin target genes have been difficult to verify because multiple upstream pathways converge on them, Axin2 has been deemed an accurate reporter of β-catenin transcriptional activity (Jho et al., 2002). In addition, we found increased β-catenin message, which is consistent with a report that β-catenin mRNA is stabilized in a feed-forward manner in cells with active Wnt signaling (Gherzi et al., 2007) (Figure 4b). Moreover, c-Jun, a proto-oncogene transcriptionally induced by β-catenin, increases nearly 3-fold in expression in tumors from Apc+/Min mice compared to those in Apc+/Δe1−15 mice (Figure 4c). Other reported β-catenin target genes, such as c-Myc and Cyclin D1, were not changed between tumors of the different genotypes (Supplementary Figure 2). These data indicate increased β-catenin activity in colon adenomas expressing truncated ApcMin.

Figure 4. Colon tumors from Apc+/Min mice appear to have higher levels of Wnt pathway activation compared to Apc+/Δe1−15 mice.

Quantitative Real-time PCR for a. Axin2, b. β-catenin, and c. c-Jun in colon tumors from aged Apc+/Δe1−15 and Apc+/Min mice. Bars, mean,*p <0.05 by Student's t test. Samples were prepared by flushing fresh colons with cold PBS and plucking colonic tumors from intestinal surface. Tissues were then minced with a razor blade before Trizol extraction for RNA. RNA was quantified by spectrophotometer, and RNA quality was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualization of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA bands. Non-degraded samples were subjected to cDNA synthesis using random primers and Superscript III reverse transcriptase. Samples were treated with RNase H to degrade template RNA after cDNA synthesis was complete. Taqman probes and reagents were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Relative expression of transcripts was determined by normalization to GAPDH.

The association between reduced β-catenin activity and more severe intestinal polyposis that we have identified here has precedent in both human and mouse studies. Through analyses of APC mutations in familial and sporadic colon cancer in humans, researchers have found a divergence from Knudson's “two-hit” hypothesis regarding inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. Specifically, the nature of “second-hit” mutations appeared to be dependent on the location of the “first-hit” in APC, indicating an active mechanism beyond simple loss of function (Alburquerque et al., 2002; Lamlum et al., 1999). The result of these APC mutations was hypothesized to yield APC gene products with some ability to downregulate β-catenin activity. While supported by in vitro studies, this idea was only recently substantiated with the development of an Apc1322T allele in mice (Pollard et al., 2009). Similar to our findings, C57BL/6 Apc+/1322T mice developed more severe polyposis and their tumors exhibited diminished nuclear β-catenin expression when compared to Apc+/Min mice. To our knowledge, our report is the first to connect the lack of Apc protein expression to submaximal β-catenin activity in the context of cancer development within a whole organism.

One way to reconcile the observed reduction in tumor phenotype despite apparently enhanced β-catenin activity in Apc+/Min mice is to postulate that excess β-catenin activity might engage oncogene-induced tumor suppressive pathways (Courtois-Cox et al., 2008). Oncogenic β-catenin ectopically expressed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts has been shown to induce expression of p19Arf to cause p53 upregulation and cell cycle arrest (Damalas et al., 2001). As tumors from Apc+/Min mice display greater β-catenin activity compared to those in Apc+/Δe1−15 mice, the reduced tumor development in Apc+/Min mice could be explained by increased activation of tumor suppressors due to enhanced oncogenic activity. Western blot analyses of colon tumors from Apc+/Min and Apc+/Min mice, however, yielded no appreciable differences in the induction of p19Arf, p53, or p21 (data not shown). Nonetheless, this notion of tumor suppressor activation in the context of high β-catenin activity requires further examination, as the lesions we interrogated were large adenomas.

Our studies demonstrate that whole-gene deletion of Apc yields more rapid tumor development than Apc truncation in mice, a result that calls into question the pro-tumorigenic effects of truncated Apc. Mice with haploinsufficiency for Apc exhibit decreased survival, more severe intestinal polyposis, and increased colonic tumor progression compared to mice bearing the ApcMin truncation. These observations support a gain-of-function role for truncated Apc, although not one that is required for tumorigenesis or advantageous for tumor development. Further genetic and molecular studies will be required to elucidate the mechanism of action. Moreover, as our studies have focused on the role of truncated Apc in adenomas and, thus, comparisons of Apc+/Min and Apc+/Δe1−15 animals in the context of additional genetic alterations, such as oncogenic K-ras and/or p53 deficiency may be further revealing. Our novel conditional and constitutive null alleles of Apc will be invaluable in these future studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Jacks labs, Keara Lane in particular, for experimental advice and assistance. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and partially by Cancer Center Support (core) grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute. T.J. is a Howard Hughes Investigator and a Daniel K. Ludwig Scholar.

REFERENCES

- Albuquerque C, Breukel C, van der Luijt R, Fidalgo P, Lage P, Slors FJM, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1549–60. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K, Taketo M. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:3327–3335. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colnot S, Niwa-Kawakita M, Hamard G, Godard C, Le Plenier S, Houbron C, et al. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois-Cox S, Jones SL, Cichowski K. Oncogene. 2008;27:2801–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damalas A, Kahan S, Shtutman M, Ben-Ze'ev A, Oren M. EMBO J. 2001;20:4912–22. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Chapelle A. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:769–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Marjou F, Janssen KP, Chang BH, Li M, Hindie V, Chan L, Louvard D, et al. Genesis. 2004;39:186–93. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R, Smits R. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2001;7:369–73. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar C, Franken P, Molenaar L, Breukel C, Van Der Valk M, Smits R, et al. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherzi R, Trabucchi M, Ponassi M, Ruggiero T, Corte G, Moroni C, et al. Plos Biol. 2007;5:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Giles R. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 2003:24. [Google Scholar]

- Haigis K, Hoff PD, White A, Shoemaker AR, Halberg RB, Dove W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9769–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403338101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis K, Kendall K, Wang Y, Cheung A, Haigis M, Glickman J, et al. Nat Genet. 2008;40:600–608. doi: 10.1038/ngXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Tamai Y, Ishikawa T, Sauer B, Takaku K, Oshima M, et al. Embo J. 1999;18:5931–42. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera L, Kakati S, Gibas L, Pietrzak E, Sandberg AA. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:473–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho EH, Zhang T, Domon C, Joo CK, Freund JN, Costantini F. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1172–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172-1183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Cell. 1996;87:159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamlum H, Ilyas M, Rowan A, Clark S, Johnson V, Bell J, et al. Nat Med. 1999;5:1071–5. doi: 10.1038/12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccartney B, Nathke I. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2008;20:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, et al. Science. 1997;275:1787–90. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathke I. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:4873–4875. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis MH, Vasen HF. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;61:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima M, Oshima H, Kitagawa K, Kobayashi M, Itakura C, Taketo M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4482–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard P, Deheragoda M, Segditsas S, Lewis A, Rowan A, Howarth K, et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2204–2213. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.058. e1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber OM, Lamlum H, Crabtree MD, Rowan AJ, Barclay E, Lipton L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2954–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042699199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits R, Kielman MF, Breukel C, Zurcher C, Neufeld K, Jagmohan-Changur S, et al. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1309–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soravia C, Berk T, Madlensky L, Mitri A, Cheng H, Gallinger S, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1290–301. doi: 10.1086/301883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, et al. Science. 1992;256:668–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs C, Baird J, Hughes E, Kent S, Benchabane H, Paik R, et al. Science. 2008;319:333–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1151232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Genesis. 2000;26:113–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<113::aid-gene3>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.