Abstract

Background and Aims

Roots typically respond to localized nitrate by enhancing lateral-root growth. Polar auxin transport has important roles in lateral-root formation and growth; however, it is a matter of debate whether or how auxin plays a role in the localized response of lateral roots to nitrate.

Methods

Treating maize (Zea mays) in a split-root system, auxin levels were quantified directly and polar transport was assayed by the movement of [3H]IAA. The effects of exogenous auxin and polar auxin transport inhibitors were also examined.

Key Results

Auxin levels in roots decreased more in the nitrate-fed compartment than in the nitrate-free compartment and nitrate treatment appeared to inhibit shoot-to-root auxin transport. However, exogenous application of IAA only partially reduced the stimulatory effect of localized nitrate, and auxin level in the roots was similarly reduced by local applications of ammonium that did not stimulate lateral-root growth.

Conclusions

It is concluded that local applications of nitrate reduced shoot-to-root auxin transport and decreased auxin concentration in roots to a level more suitable for lateral-root growth. However, alteration of root auxin level alone is not sufficient to stimulate lateral-root growth.

Keywords: Nitrate, auxin transport, lateral roots, maize, Zea mays

INTRODUCTION

Nutrients are unevenly distributed within the soil horizon under both natural and field conditions (Jackson and Caldwell, 1993; Robinson et al., 1994; Sattelmacher and Thomas, 1995). Plant roots have developed morphological and physiological plasticity in response to nutrient enrichment. In many plant species nutrient-rich soil strata or patches stimulate local lateral-root proliferation (Farley and Fitter, 1999).

In well-aerated agricultural soils, nitrate (NO3−) is the main form of available inorganic nitrogen utilized by higher plants. Lark et al. (2004) reported that variation in soil nitrate concentration can be as large as 100-fold within a distance of 4 m. It has been demonstrated that a localized supply of nitrate can stimulate the initiation and/or elongation of lateral roots (Brouwer, 1962; Hackett, 1972; Drew, 1975; Drew and Saker, 1975; Granato and Raper, 1989; Zhang and Forde, 1998).

The stimulation of lateral-root growth appears to be attributable to a signalling effect from the nitrate ion itself rather than to a downstream metabolite (Zhang and Forde, 1998; Zhang et al., 1999). One component of the nitrate signalling pathway, identified in Arabidopsis thaliana is a member of the MADS box family of transcription factors, called ANR1 (Zhang and Forde, 1998; Walch-Liu et al., 2006). Recently it was found that ANR1 acts downstream of the nitrate transporter AtNRT1·1, in mediating the stimulatory effect of a localized nitrate supply on lateral-root proliferation (Remans et al., 2006).

Polar auxin transport and the auxin signalling pathways have essential roles in lateral-root formation, particularly during lateral-root initiation and primordium development (Casimiro et al., 2001; Benková et al., 2003; Casimiro et al., 2003; De Smet et al., 2007). In roots, IAA transported away from the root tip towards the shoot (i.e. basipetally) is required for the initiation of lateral-root primordia, while acropetally transported IAA from the shoot is required for their subsequent growth (Bhalerao et al., 2002). Polar auxin transport is mediated by auxin influx (AUX1/LAX) and efflux carriers (PINs and MDR/PGPs) (Friml, 2003; Geisler et al., 2005, 2006). AUX1 regulates lateral-root initiation and emergence by facilitating the export of IAA from newly developing leaf primordia, unloading IAA in the primary root apex, and import of IAA into developing lateral root primordia (Marchant et al., 2002). Roots of the aux1-7 mutant which do not express AUX1 exhibit a 50 % reduction in the number of lateral root primordia (Hobbie and Estelle, 1995; Marchant et al., 2002). Lateral-root formation in A. thaliana involves dynamic gradients of auxin with maximal concentrations of auxin being present at the primordia tips (Benková et al., 2003). These gradients are mediated by cellular efflux requiring asymmetrically localized PIN proteins.

Polar auxin transport also depends on a group of ABC transporters belonging to the multidrug resistance (MDR)-like family, also known as the P-glycoproteins (PGPs) (ABCBx) (Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2001; Martinoia et al., 2002). Recently, it was found that auxin transport mediated by MDR1 had a role in controlling lateral-root elongation. Impaired acropetal auxin transport due to mutation of the MDR1 gene caused 21 % of nascent lateral roots to arrest their growth and the remainder to elongate 50 % more slowly than the wild type. Furthermore, the slow elongation of mdr1 lateral roots was rescued by auxin (Wu et al., 2007).

Few studies have evaluated the role of auxin in local nitrate-induced lateral-root growth. In maize, Sattelmarcher and Thoms (1995) observed a transient increase of IAA in nitrate-rich root segments after treatment for 3 d. They hypothesized that localized nitrate stimulates lateral-root growth by increasing auxin unloading and accumulation in the nitrate-fed root segments. In A. thaliana, Zhang et al. (1999) compared lateral-root growth rate in response to local nitrate supply for three auxin mutants, aux1, axr2 and axr4, and found that axr4 was insensitive to the nitrate, suggesting there is an overlap between the signal transduction pathways for auxin and nitrate in determining lateral-root growth. However, in contrast, Linkohr et al. (2002) found a wild-type pattern of lateral root response to localized nitrate for axr4 and concluded that auxin is not required for this response. Most recently Krouk et al. (2010) proposed that the nitrate transporter, NRT1·1, could also transport auxin, once again linking nitrate and auxin signalling pathways.

Maize is a grass and thus has a distinctly different root architecture from that of A. thaliana (Hochholdinger et al., 2004) and little work has been undertaken to understand the mechanism of the lateral-root growth response localized to nitrate and to what extent that response is linked to auxin. That the responses are linked has been suggested by Guo et al. (2005) on the basis of experiments with an auxin transport inhibitor; however, those authors did not document auxin transport and it remains unclear to what extent, if any, auxin transport in roots is regulated by localized nitrate in maize.

To elucidate further the relationship between auxin and localized nitrate in maize, [3H]IAA was used to quantify auxin transport. The effects of exogenous auxin and polar auxin transport inhibitors were also examined. The results suggest that local applications of nitrate reduced shoot-to-root auxin transport and decreased auxin concentration in roots to a level more suitable for lateral-root growth. Nevertheless, alteration of root auxin level alone is not sufficient to stimulate lateral-root growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant culture

Maize (Zea mays L. ‘Y478’) seeds were sterilized with 10 % (v/v) H2O2 for 30 min, washed with distilled water, soaked in saturated CaSO4 for 6 h and then put to germinate on moist filter paper for 2 d in the dark at room temperature. Germinated seeds were transferred to silica sand to continue growing. Uniform seedlings with two visible leaves were selected and, after the endosperms had been removed, were placed in porcelain pots containing 1 L nutrient solution. Each pot contained three plants. These plants were then put in a growth chamber controlled at 28/22 °C during a 14/10 h light/dark cycle. A photosynthetic photon flux density of 250–300 µmol m−2 s−1 (at canopy height) was provided during the 14-h light period. The nutrient composition in the solution was: (in mm) 0·75 K2SO4, 0·1 KCl, 0·25 KH2PO4, 0·65 MgSO4, and 0·1 EDTA-Fe, and (in μM) 1·0 MnSO4, 1·0 ZnSO4, 0·1 CuSO4 and 0·005 (NH4)6Mo7O24. Nitrogen in the form of Ca(NO3)2 was added according to experimental requirements. Solution pH was adjusted to 6·0. The nutrient solution was aerated continuously using an electric pump and was renewed every 2 d.

Plants were pre-cultured in the above solution containing 0·5 mm nitrate for about 6 d. Plants had developed four crown roots at this stage. The primary root and all the seminal roots were removed and only the four crown roots remained (Stamp et al., 1997). After 1 d of recovery in the same solution as above, plants were grown in the nutrient solution without nitrate for 2 d before being transferred to a split-root system where half of the roots were supplied with 0·5 mm Ca(NO3)2 (+N) and the other half supplied with 0·5 mm CaCl2 (–N). The volume of each compartment of the split-root system was 1 L. Three plants were cultured in each split-root system and were pooled as one sample for root measurement at the time indicated.

Measurement of lateral-root length and density

The root system was spread out, roots were scanned and images were analysed for lateral-root length using WinRhizo Pro system (Canada). Lateral roots were counted and lateral-root density was calculated from the image. In previous studies (Guo et al., 2005; Han et al., 2009), the density of first-order lateral roots was seldom affected by nitrate, even though in the root segment where lateral-root primodia have not initiated when localized nitrate treatment is applied. In this study, therefore, lateral-root length and density were determined within a 5-cm root segment where lateral root primordia had emerged at the time of split-root treatment.

[3H]IAA transport assay

The [3H]IAA transport assay was conducted at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, St Louis, MO, USA. To assay the effects of nitrate supply on auxin transport, plants were pre-cultured as described as above. Auxin transport was assayed 1 d after localized or uniform nitrate treatment by means of [3H]IAA as described below.

Shoot-to-root auxin transport in intact plants was assayed according to Murphy et al. (2000) and Geisler et al. (2005). In brief, maize shoots were removed at 2 cm above the root–shoot joint and 20 µL of [3H]IAA solution was applied to the cut surface. Plants were kept in darkness for 18 h (overnight). Four root segments were then sampled: (1) the root tip (0·5 cm); (2) the segment in which lateral-root initiation and emergence occurred (no lateral roots were visible in this segment at the start of the treatment); (3) the lateral-root elongation segment where lateral roots were visible but their length was not as long as that of mature lateral roots; and (4) the mature lateral-root segment. Ten replicate roots were sampled. Each of the above four segments was dissected and paired root samples were analysed. Samples were weighed before being incubated in scintillation solution (5 mL) for >18 h. Radioactivity from 3H was then detected using a Beckman Coulter LS6500 multipurpose scintillation counter.

Measurement of auxin transport in excised root segments was conducted according to Okada et al. (1991). Transport toward the root tip (i.e. acropetal) was assayed in root segments 3–6 cm from the root tip and transport away (i.e. basipetal) was assayed in root segments 0–3 cm from the root tip. Root segments were placed horizontally on a plastic film and 3 µL [3H]IAA was applied to one end of the root segments. For acropetal transport, [3H]IAA was applied to the morphologically upper end. For basipetal transport, [3H]IAA was applied to the root tip. Root segments were kept in a humid and dark environment for 18 h (overnight). The root segments were then divided into two parts: (1) 1 cm of the distal end and (2) the remaining 2 cm. Radioactivity was detected as described above.

The [3H]IAA solution used contained 0·5 µm [3H]IAA (20 Ci mmol−1) in 2 % DMSO, 25 mm MES (pH 5·2) and 0·25 % agar.

IAA extraction and determination

IAA extraction and measurement was conducted at the Analytical Center, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, according to the method of Edlund et al. (1995). In brief, 200- to 300-mg root samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen in an Eppendorf tube and transferred to a 10-mL test tube by using 5 mL 80 % MeOH containing 0·02 % (w/v) sodium diethyldithiocarbamate as an antioxidant. Two microlitres of [13C6]IAA (10 ng μL−1) were added as an internal standard, and the sample was extracted under continuous shaking for 1 h at 4 °C in the dark. After extraction, the pH of the supernatant was adjusted to approx. 2·5–3·0 with 2 n HC1 and was extracted three times using ethyl acetate. The combined organic fractions were reduced to dryness in a speed-vac concentrator. The sample was dissolved in 0·1 m acetic acid and purified using C18 cartridges. The purified sample was dried and transferred for further purification of the IAA–sugar conjugate, and was then assayed using GC-MS (GC: Trace 2000, ThermoQuest CE Instruments; MS: Voyager, ThermoQuest Finningan)

Exogenous auxin and polar auxin transport inhibitors

α-Naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) and IAA (Sigma) were dissolved in 1 m NaOH. N-1-Naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) (ChemService, USA) were dissolved in DMSO.

RESULTS

Stimulation of lateral-root growth by localized nitrate

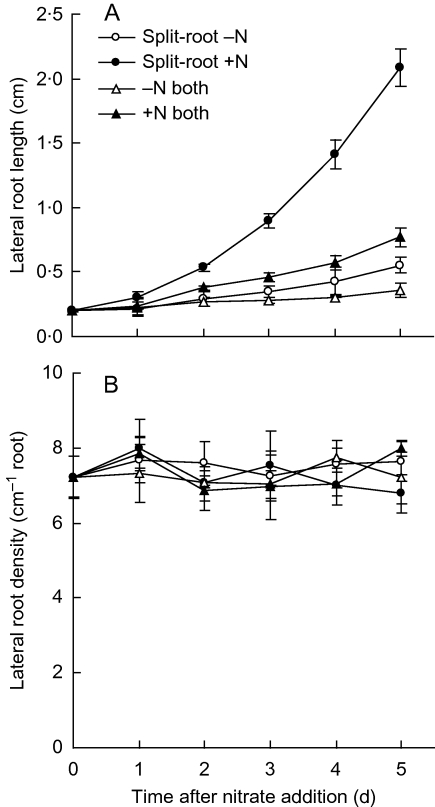

To examine the effects of localized nitrate treatment, a split-root system was used in which 7-d-old seedlings were starved of nitrogen for 2 d and then transferred for treatment to a split-root system, with two roots in each compartment. At 5 d of treatment, lateral-root length in the compartment containing nitrate was almost 5·8 times greater than that of uniformly nitrate-starved roots, whereas lateral-root length in the nitrate-free compartment was slightly but not significantly greater than uniformly starved roots (Fig. 1A). This establishes a system where a localized response to nitrate occurs. However, lateral-root length in the plus-nitrate compartment was also far greater than for root systems treated uniformly with nitrate (compare circles with triangles in Fig. 1A), which demonstrates that the nitrate-starved side of the root system plays a role in the localized response, presumably by generating a signal.

Fig. 1.

Maize lateral root growth in response to localized nitrate supply: (A) length of lateral roots; (B) lateral-root density. Plants with four nodal roots were starved of nitrogen for 2 d and then transferred into a two-compartment split-root system where half of the roots were supplied with 0·5 mm Ca(NO3)2 (+N) and the other half supplied with 0·5 mm CaCl2 (–N). Data represent the mean ± standard error of four replicates.

Localized nitrate had little if any effect on the density of first-order lateral roots (Fig. 1B) showing that the measured length responses shown were due to exclusively to growth. However, with treatment longer than for 5 d, when first-order lateral roots had become longer, second-order lateral roots were numerous for nitrate-fed roots but rare for nitrate-starved roots. These second-order lateral roots apparently formed during the first 5 d of treatment, as determined by examination through the microscope (data not shown), but were too short to measure.

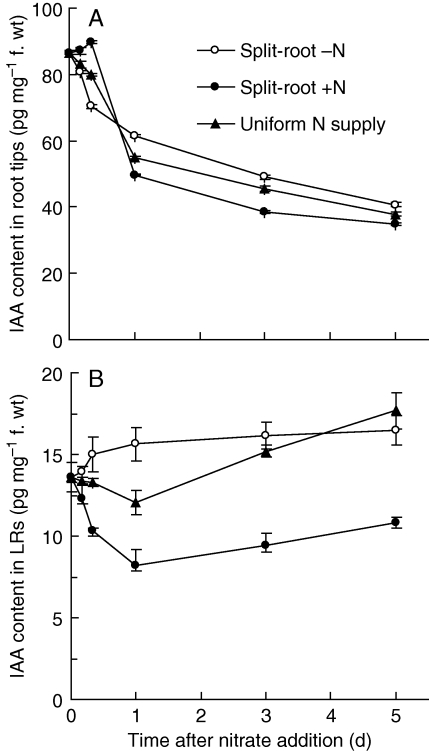

Auxin levels in roots

Auxin levels in root tips and lateral root-growing regions were determined. Under uniform nitrate supply, auxin concentration in the root tip decreased continuously after the addition of nitrate (Fig. 2A). A slight reduction in auxin concentration was observed in lateral roots 1 d after nitrate treatment, but auxin concentration increased thereafter until the end of the experiment (Fig. 2B). For the split-root system, the kinetics was more complex. During the first 8 h of treatment, the minus-nitrate root tips appeared to undergo an accelerated decrease in auxin level whereas the plus-nitrate tips increased in auxin level. For the next 16 h, auxin levels in the plus-nitrate root tips decreased sharply so that they became significantly less than those in the minus-nitrate tips (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the lateral root-growing region maintained a roughly constant level of auxin for the 5-d period (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless, the behaviour of the two sides of the split-root system differed notably, with the auxin levels increasing in the minus nitrate side and decreasing substantially in the plus-nitrate side. Insofar as auxin is an inhibitor of root growth, the generally lower levels in plus-nitrate roots are consistent with their greater growth.

Fig. 2.

Effect of nitrate treatments on the concentration of IAA in root tips (A) and lateral roots (B). Plants were treated as for Fig. 1. The IAA concentration in root tips and lateral roots was determined at 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, 1 d, 3 d and 5 d after nitrogen treatments. Data represent the mean ± s.e. of four replicates.

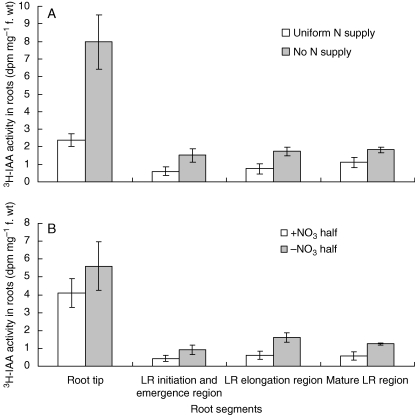

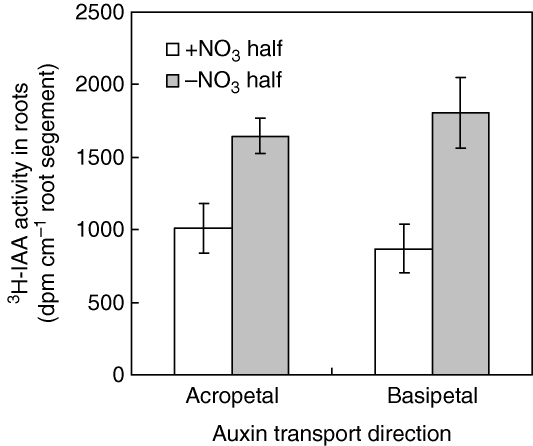

[3H]IAA transport

To account for the different auxin levels, auxin transport we measured using radiolabelled IAA. Plants handled as above in the split-root system were assayed after 1 d of treatment. First, IAA transport from shoot to root (acropetal) was determined in response to uniform nitrate supply. The uniform nitrate treatment substantially reduced the amount of [3H]IAA reaching the roots, especially the root tip (Fig. 3A), suggesting that acropetal IAA transport was inhibited by elevated nitrogen nutrition. Then IAA transport in the two halves of the split-root system was compared. Again, nitrate inhibited auxin transport but the difference was smaller than for the uniform treatment although still significant (P < 0·05 between the auxin levels between the nitrate-fed and nitrate-free roots), especially in the elongating and mature lateral-root regions (Fig. 3B). Finally, basipetal (away from the root tip) transport, which was substantially reduced in the plus-nitrate roots, was assayed (Fig. 4). In this experiment, it was possible to make an independent measurement of acropetal transport because the roots were excised for the assay, and this confirmed the lower acropetal IAA transport in plus-nitrate roots shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

[3H]IAA transport: (A) uniform nitrate supply; (B) localized nitrate supply. Plants were pre-cultured in the same experimental system as in Fig. 1. Radiolabelled IAA was given after 1 d of treatment, as described in Materials and Methods. Plants were kept in the dark for 18 h before being assayed for radioactivity in the indicated regions; LR, lateral root. Data represent the mean ± s.e. of four replicates.

Fig. 4.

Acropetal and basipetal [3H[IAA transport in response to localized nitrate supply. Plants were pre-cultured in the same split-root system as in Fig. 1. One day after the addition of nitrate, a 3-cm apical segment was used for assay. [3H[IAA was applied either at the root tip (for basipetal IAA transport) or to the cut surface (for acropetal IAA transport) and the root segments were kept in darkness for 18 h. The distal 1-cm region was counted. Data represent the mean ± s.e. of four replicates.

Effect of exogenous auxin and polar auxin transport inhibitors

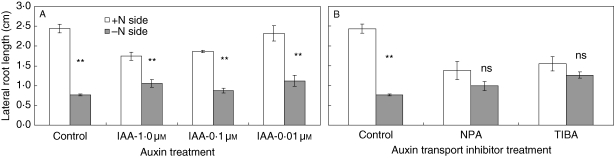

Do decreased auxin levels contribute to the stimulatory effect of localized nitrate on lateral-root growth? To answer this question, exogenous IAA was applied to the plus-nitrate roots compartment in the split-root system (Fig. 5A). With the presence of 0·01–1 µm IAA, the effect of localized nitrate on lateral-root length was greatly inhibited (by 32–39 %), but not completely abolished, i.e. localized nitrate still increased lateral-root length by about 2-fold. A synthetic auxin NAA had a similar effect (data not shown). Therefore, only about one-third of the promotion of lateral-root length brought about by nitrate might be attributable to a reduction in endogenous auxin. Interestingly, IAA given to the plus-nitrate compartment stimulated slightly the length of lateral roots in the nitrate-free compartment. Although the mechanism was not investigated here, it has often been observed that when lateral-root growth of one side of the split-root system was inhibited, that of the other side was somewhat enhanced. The same situation was also found in the following auxin treatments (Figs 5B and 6).

Fig. 5.

Effect of auxin status on lateral-root length in roots supplied with localized nitrate: (A) IAA treatment; (B) treatment with the polar auxin transport inhibitors, NPA or TIBA. Compounds were added to the nitrate-fed compartment of the split-root system. Data represent the mean ± s.e. of four replicates. **, Significant difference between the lateral-root length in the two root halves at P < 0·01.

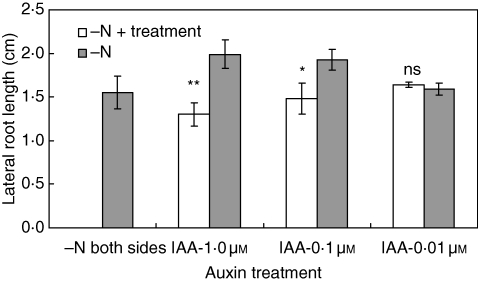

Fig. 6.

Effect of localized supply of auxin on lateral-root length in nitrate-starved plants. Plants were nitrogen-starved for 2 d before transfer to a split-root system. IAA was added to one compartment. Data represent the mean ± s.e. of four replicates. The difference between the lateral-root lengths in the two halves was significant at P < 0·01 (**) and P < 0·05 (*) or non-significant (ns).

When polar auxin transport inhibitors, NPA or TIBA, were applied to the plus-nitrate compartment, the ability of nitrate to promote lateral roots was essentially lost (Fig. 5B). This suggests that a polar auxin transport system is necessary for lateral roots to grow at all.

To investigate the impact of auxin level in nitrate-starved roots, IAA was supplied to one compartment of uniformly nitrate-free roots. A localized supply of IAA at 0·01 µm did not affect lateral-root length (Fig. 6). When 0·1 or 1·0 µm IAA was added, the length of lateral roots in the treated compartment was reduced significantly compared with the untreated half. These results are consistent with the idea that the IAA level in minus-nitrate roots is super-optimal for lateral-root growth.

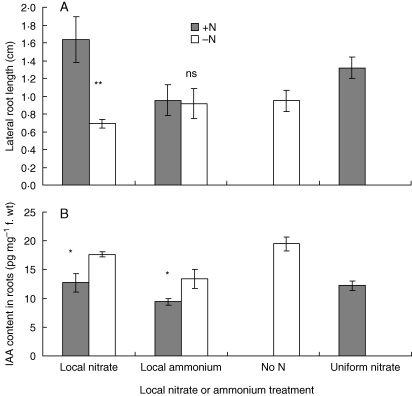

Effect of local application of ammonium on lateral-root growth and auxin concentration in roots

The above data suggest that the alternation of IAA concentration in the root, while beneficial, might not be necessary for stimulating lateral-root growth. To clarify this, whether or not the reduction of auxin in nitrate-fed roots was specific to nitrate was checked. A localized supply of ammonium treatment did not increase lateral-root growth (Fig. 7A), but it did reduce auxin concentration in the ammonium-fed roots by about as much as the localized nitrate treatment did (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the reduction of auxin in nitrate-fed roots might be a response to increased nitrogen nutrition rather than a step in the pathway that induces the growth of lateral roots in response to nitrate.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of the effect of localized supply of nitrate or ammonium: (A) lateral-root growth; (B) IAA concentration. Plants were treated as for Fig. 1. For the ammonium treatment, one half received 0·5 mm 0·5 mmol L−1 (NH4)2SO4, while the other half received CaCl2. IAA and lateral-root length were measured 3 d and 4 d later, respectively. Data represent the mean ± s.e. of four replicates. The difference between the length (A) and IAA concentration (B) of lateral roots in the two halves was significant at P < 0·01 (**) and P < 0·05 (*) or non-significant (ns).

DISCUSSION

With uniform nitrate treatment, auxin levels in roots are reduced with increasing nitrate supply; this has been observed in soybean (Caba et al., 2000), A. thaliana (Walch-Liu et al., 2006; Bao et al, 2007) and maize (Tian et al, 2008). Under a localized nitrate supply, Sattelmacher and Thomas (1995) found a transient increase in IAA in nitrate-fed root segments 2 d after treatment. Here, a transient (within 8 h) increase of IAA was observed in the root tip of nitrate-fed roots. In root segments with growing lateral roots, however, IAA levels in the plus-nitrate compartment decreased continuously and were always lower that those in the minus-nitrate compartment (Fig. 2). Radiotracer experiments suggested that a uniform nitrate supply reduced shoot-to-root IAA transport (Fig. 3). These data indicate that auxin transport to the lateral root-growing region of nitrate-fed roots was reduced by a localized nitrate supply. Therefore, the present results are not in full agreement with those of Sattelmacher and Thomas (1995).

Although both uniform and localized nitrate supply reduced auxin levels in root tips in comparison with nitrate starvation, localized nitrate treatment was more effective than uniform treatment (Fig. 2A). In lateral root-growing regions, the auxin level was only slightly reduced 1 d after the roots were moved from nitrate-free to uniform nitrate treatment. However, when only half of the roots were given nitrate (localized nitrate treatment), the auxin level in a lateral root-growing segment decreased sharply and concomitantly, in the nitrate-minus roots, auxin levels increased. Although the movement of [3H]IAA suggested that less IAA reached the root tips in nitrate-fed roots, the effect was much stronger with uniform nitrate treatment, suggesting that the acropetal auxin transport system plays only a small part in the changes in auxin level seen in the split-root system with localized nitrate supply.

Previously, it had been found that the expression of auxin influx transporter AUX1 was high in low-nitrate-treated A. thaliana roots (Bao et al., 2007). Therefore, it might be hypothesized that localized nitrate supply caused uneven distribution of auxin between nitrate-fed and nitrate-free roots by regulating the auxin transport system. Here with split roots, the effect of localized nitrate on stimulating lateral-root growth as well as on reducing auxin levels was enhanced compared with a uniform nitrate treatment. Therefore, there must be communication between the root systems or between them and the shoot. Such a signal might be a shoot-derived systemic signal conveying information about the overall nitrogen status (Zhang et al., 1999). When part of the root system is nitrate-starved while another part experiences plentiful nitrate, the response to the nitrate will occur in a background where half of the root system presumably continues to emit a nitrate-starvation signal. It might be the continued presence of this signal that strengthens the response to localized nitrate. By contrast, when the entire root system is supplied with nitrate, the internal nitrogen-starvation signal is weakened and, as a result, the response to nitrate is weaker.

It is known that auxin is actively transported basipetally in the shoot and inhibits bud outgrowth (Ongaro and Leyser, 2008). While auxin is essential for lateral-root initiation, it is not clear how auxin regulates lateral-root growth in roots. Auxin concentration in roots is widely regarded as being super-optimal for elongation, although there are a few reports where small stimulations are seen following treatment with extremely low levels (e.g. Tian et al., 2008). It was found that a localized supply of a high dose of IAA arrested lateral-root elongation in Pontaderia cordata (Charlton, 1996). Since nitrate treatment often leads to reduced auxin levels in roots (Fig. 2; Caba et al., 2000; Bao et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2008), we hypothesized that these reduced auxin levels are permissive for lateral-root growth. If this hypothesis is true, increasing IAA levels in the roots by supplying exogenous IAA should abolish or at least reduce the stimulatory effect of the localized nitrate supply. Indeed, exogenous IAA did reduce the stimulatory effect of localized nitrate on lateral-root growth by about one-third (Fig. 5) and exogenous IAA inhibited lateral-root growth, even at the lowest concentrations tested (Fig. 6).

Although IAA levels in the roots of nitrate-starved plants might be too high for optimal lateral-root growth, a reduction in root IAA level alone was insufficient to enhance lateral-root growth. Localized nitrate treatment reduces auxin levels in both nitrate-fed and nitrate-free roots but lateral-root growth was stimulated only in the nitrate-fed side (Fig. 2). In addition, localized treatment with ammonium also reduced IAA levels, to about the same extent as in the localized nitrate treatment, but did not stimulate lateral-root growth (Fig. 7). Similarly IAA concentration in wheat roots uniformly fed with ammonium was lower as compared with nitrate treatment (Kudoyarova et al., 1997). Previously it has been shown that localized ammonium increased lateral-root number (Drew, 1975), but inhibited lateral-root length (Drew, 1975; Schortemeyer et al., 1993). This suggests that the reduction in auxin concentration in roots as a whole was not a specific response to a localized nitrate supply. Rather, it might reflect improved nitrogen status in the plants (Walch-Liu et al., 2006; Bao et al, 2007; Tian et al, 2008).

In contrast to the results here, Guo et al. (2005) reported that 0·1 µm NAA did not affect the localized nitrate-induced lateral root. The reason for the difference is not clear. Although those authors used the same maize genotype as in the present study, they used a different treatment method, in which nitrate and NAA were supplied locally in the middle strip of a three-layer agar system. In the present split-root solution culture system, exogenous IAA was supplied to the whole root system in a nitrate-fed compartment and therefore represents a more systemic auxin treatment. Nevertheless, the fact that Guo et al. (2005) found that the lateral-root growth response to localized nitrate was unaltered by concomitant auxin treatment strengthens our suggestion that the decreased auxin levels, although permissive, are not required for the stimulation of lateral-root growth by nitrate.

In conclusion, the results suggest that local applications of nitrate reduced shoot-to-root auxin transport and reduced auxin concentration in roots to a level more suitable for lateral-root growth. Nevertheless, alteration of root auxin level alone is not sufficient to ensure stimulation of lateral-root growth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2009CB11860) and the innovative group grant of NSFC (No. 30821003, 30771289). We thank D. Schachtman, Danforth Plant Science Center, USA, for assistance with the [3H]IAA assay.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bao J, Chen F, Gu R, Wang G, Zhang F, Mi G. Lateral root development of two Arabidopsis auxin transport mutants, aux1-7 and eir1-1, in response to nitrate supplies. Plant Science. 2007;173:417–425. [Google Scholar]

- Benková E, Michniewicz M, Sauer M, et al. Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell. 2003;115:591–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalerao RP, Eklöf J, Ljung K, Marchant A, Bennett M, Sandberg G. Shoot-derived auxin is essential for early lateral root emergence in Arabidopsis seedlings. The Plant Journal. 2002;29:325–332. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer R. Nutritive influences on the distribution of dry matter in the plant. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science. 1962;10:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- Caba JM, Centeno ML, Fernández B, Gresshoff PM, Ligero F. Inoculation and nitrate alter phytohormone levels in soybean roots: differences between a supernodulation mutant and the wild type. Planta. 2000;211:98–104. doi: 10.1007/s004250000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro I, Marchant A, Bhalerao RP, et al. Auxin transport promotes Arabidopsis lateral root initiation. The Plant Cell. 2001;13:843–852. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro I, Beeckman TN, Graham R, et al. Dissecting Arabidopsis lateral root development. Trends in Plant Science. 2003;8:165–171. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton WA. Lateral root initiation. In: Waisel Y, Eshel A, Kafkafi U, editors. Plant roots: the hidden half. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1996. pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- De Smet I, Tetsumura T, De Rybel B, et al. Auxin-dependent regulation of lateral root positioning in the basal meristem of Arabidopsis. Development. 2007;134:681–690. doi: 10.1242/dev.02753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC. Comparison of the effects of a localized supply of phosphate, nitrate, ammonium and potassium on the growth of the seminal root system and the shoot in barley. New Phytologist. 1975;75:479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC, Saker LR. Nutrient supply and the growth of the seminal root system of barley. II. Localized, compensatory increases in lateral root growth and rates of nitrate uptake when nitrate supply is restricted to only part of the root system. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1975;26:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund A, Eklof S, Sundberg B, Moritz T, Sandberg G. A microscale technique for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry measurements of picogram amounts of indole-3-acetic acid in plant tissues. Plant Physiology. 1995;108:1043–1047. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley RA, Fitter AH. Temporal and spatial variation in soil resources in a deciduous woodland. Journal of Ecology. 1999;87:688–696. [Google Scholar]

- Friml J. Auxin transport – shaping the plant. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2003;6:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s1369526602000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M, Murphy AS. The ABC of auxin transport: the role of p-glycoproteins in plant development. FEBS Letters. 2006;580:1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M, Blakeslee JJ, Bouchard R, et al. Cellular efflux of auxin catalyzed by the Arabidopsis MDR/PGP transporter AtPGP1. The Plant Journal. 2005;44:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato TC, Raper CD. Proliferation of maize (Zea mays L.) roots in response to localized supply of nitrate. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1989;40:263–275. doi: 10.1093/jxb/40.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Chen F, Zhang F, Mi G. Auxin transport from shoot to root is involved in the response of lateral root growth to localized supply of nitrate in maize. Plant Science. 2005;169:894–900. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett C. A method of applying nutrients locally to roots under controlled conditions and some morphological effects of locally applied nitrate on the branching of wheat roots. Australian Journal of Biological Science. 1972;25:1169–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Cheng F, Wu D, Zhang F, Mi G. Effects of localized supplement of nitration and ammonium on lateral root growth of maize under different pH conditions. Journal of Maize Science. 2009;17:99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie L, Estelle M. The axr4 auxin-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana define a gene important for root gravitropism and lateral root initiation. The Plant Journal. 1995;7:211–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.7020211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholdinger F, Park WJ, Sauer M, Woll K. From weeds to crops: genetic analysis of root development in cereals. Trends in Plant Science. 2004;9:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RB, Caldwell MM. The scale of nutrient heterogeneity around individual plants and its quantification with geostatistics. Ecology. 1993;74:612–614. [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G, Lacombe B, Bielach B, et al. Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1·1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Developmental Cell. 2010;18:927–937. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoyarova GR, Farkhutdinov RG, Veselov SY. Comparison of the effects of nitrate and ammonium forms of nitrogen on auxin content in roots and the growth of plants under different temperature conditions. Plant Growth of Regulation. 1997;23:207–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lark RM, Milne AE, Addiscott TM, Goulding KWT, Webster CP, O'Flaherty S. Scale- and location-dependent correlation of nitrous oxide emissions with soil properties: an analysis using wavelets. European Journal of Soil Science. 2004;55:611–627. [Google Scholar]

- Linkohr BI, Williamson LC, Fitter AH, Leyser HMC. Nitrate and phosphate availability and distribution have different effects on root system of architecture of Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2002;29:751–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant A, Bhalerao R, Casimiro I, et al. AUX1 promotes lateral formation by facilitating indole-3-acetic acid distribution between sink and source tissues in the Arabidopsis seedling. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:589–597. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinoia E, Klein M, Geisler M, et al. Multifunctionality of plant ABC transporters: more than just detoxifiers. Planta. 2002;214:345–355. doi: 10.1007/s004250100661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Peer WA, Taiz L. Regulation of auxin transport by aminopeptidases and endogenous flavonoids. Planta. 2000;211:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s004250000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Ueda J, Komaki MK, Bell CJ, Shimura Y. Requirement of the auxin polar transport system in early stages of Arabidopsis floral bud formation. The Plant Cell. 1991;3:677–684. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.7.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongaro V, Leyser O. Hormonal control of shoot branching. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;57:67–74. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remans T, Nacry P, Pervent M, et al. The Arabidopsis NRT1·1 transporter participates in the signaling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate-rich patches. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:19206–19211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605275103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Linehan DJ, Gordon DC. Capture of nitrate from soil by wheat in relation to root length, nitrogen inflow and availability. New Phytologist. 1994;128:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Fernández R, Davies TGE, Coleman JOD, Rea PA. The Arabidopsis thaliana ABC protein superfamily, a complete inventory. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:30231–30244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattelmacher B, Thoms K. Morphology and physiology of the seminal root system of young maize (Zea mays L.) plants as influenced by a locally restricted nitrate supply. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenernährung und Bodenkunde. 1995;158:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Schortemeyer M, Feil B, Stamp P. Root morphology and nitrate uptake of maize simultaneously supplied with ammonium and nitrate in a split-root system. Annals of Botany. 1993;72:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Stamp P, Feil B, Schortemeyer M, Richner W. Responses of roots to low temperatures and nitrogen forms. In: Anderson HM, et al., editors. Plant roots: from cells to systems. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher; 1997. pp. 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q, Chen F, Liu J, Zhang F, Mi G. Inhibition of maize root growth by high nitrate supply is correlated to reduced IAA levels in roots. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2008;165:942–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walch-Liu P, Ivanov II, Filleur S, Gan Y, Remans T, Forde B. Nitrogen regulation of root branching. Annals of Botany. 2006;97:875–881. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcj601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Lewis DR, Spalding EP. Mutations in Arabidopsis multidrug resistance-like ABC transporters separate the roles of acropetal and basipetal auxin transport in lateral root development. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:1826–1837. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HM, Forde BG. An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science. 1998;279:407–409. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HM, Jennings A, Barlow PW, Forde BG. Dual pathways for regulation of root branching by nitrate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1999;96:6529–6534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]