Abstract

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is a common medical condition in pregnancy with significant physical and psychological morbidity. Up to 90% of women will suffer from NVP symptoms in the first trimester of pregnancy with up to 2% developing hyperemesis gravidarum which is NVP at its worst, leading to hospitalization and even death in extreme cases. Optimal management of NVP begins with nonpharmacological approaches, use of ginger, acupressure, vitamin B6, and dietary adjustments. The positive impact of these noninvasive, inexpensive and safe methods has been demonstrated. Pharmacological treatments are available with varying effectiveness; however, the only drug marketed specifically for the treatment of NVP in pregnancy is Diclectin® (vitamin B6 and doxylamine). In addition, the Motherisk algorithm provides a guideline for use of safe and effective drugs for the treatment of NVP. Optimal medical management of symptoms will ensure the mental and physical wellbeing of expecting mothers and their developing babies during this often stressful and difficult time period. Dismissing NVP as an inconsequential part of pregnancy can have serious ramifications for both mother and baby.

Keywords: pharmacological/nonpharmacological treatments, NVP

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is a debilitating condition affecting many pregnant women. Up to 90% of pregnant women will experience NVP of varying severity, with symptoms generally starting around 4–9 weeks of gestation, peaking around the 7th to 12th week, and subsiding by the 16th week.1–3 NVP symptoms will appear prior to ten weeks of gestation;1 women who experience NVP symptoms for the first time after 10 weeks, may be experiencing nausea and vomiting due to other medical conditions.4 The diagnosis of NVP is clinical in nature, and although other causes of persistent nausea, retching and/or vomiting are rarely encountered, failure to distinguish them from NVP can result in serious complications.5 Table 1 summarizes the differential diagnosis of patients with suspected NVP.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of NVP

Gastrointestinal

|

Genitourinary tract

|

Metabolic

|

Neurologic disorders

|

Miscellaneous

|

Pregnancy-related condition

|

About 20%–30% of pregnant women will experience symptoms beyond 20 weeks, up to time of delivery.1,6,7 Less than 2% of women with NVP symptoms will develop hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), characterized by protracted vomiting leading to fluid and electrolyte imbalance, nutrition deficiency and a weight loss of more than 5% of the pre-pregnancy weight, often leading to hospitalization.8 Approximately 10% of HG patients will have persisting symptoms throughout pregnancy.1 To reduce symptoms and subsequent suffering, as soon as NVP commences, women and their health care providers should intervene with the appropriate treatment to prevent HG from occurring.9

Generally it has been observed that women who experience NVP have better pregnancy outcomes than those who don’t, and women who use antiemetics appear to have better pregnancy outcomes than women with NVP who don’t receive treatment.10 One explanation for this is that women who use antiemetics, tend to experience severe NVP which may be associated with a more robust placenta secreting high levels of hCG hormones; thus the better outcome for the antiemetic group of women could be attributed to the placenta itself and not so much the therapy.10

Despite many theories, the etiology of NVP remains unknown. Hormonal, immunological, anatomical and even psychological contributors to NVP and HG have been proposed, although inconsistently, in many studies. Results to date remain inconclusive,8,9 as the cause is most likely multifactorial. Certain risk factors for experiencing NVP that have been proposed include decreased maternal age, increased placental mass, genetic predisposition, previous history of HG, multipara, fetal gender, and helicobacter pylori infection.9,11,12 A recent study examined potential risk factors regarding timing of onset, severity, and duration of NVP symptoms in more than 2000 women. It was reported that the duration of NVP is reduced in older women as well as non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women, and is increased with higher gravidity; however, severity of NVP was not associated with any of the aforementioned risk factors.13

NVP, especially HG, can be quite traumatic, both physically and mentally.14–16 In the absence of vomiting and retching, nausea alone can still have a detrimental effect on women’s wellbeing.14,17 Negative maternal consequences have been reported even postpartum; these include longer recovery time from pregnancy and persistence of symptoms post delivery with greater intensity for women who had extreme weight loss.18 These symptoms include postpartum gallbladder dysfunction, food aversions, muscle pain, nausea, and symptoms characteristic of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18

In addition to maternal consequences, negative impact of NVP on the fetus, family relationships, and job performance has also been documented.12,19 The most common adverse fetal outcome with severe vomiting is low birth weight and preterm birth; the more severe the nausea and vomiting, the lower the birth weight.9,12 Women report that their impairment due to nausea and vomiting compromises their parenting ability, as well as job performance, and very often family relationships are strained as a result of this distress.14 Moreover, the significant psychosocial morbidity caused by severe symptoms has resulted in elective pregnancy terminations, because women feel they cannot continue a pregnancy under these circumstances.9,14,20

A number of nonpharmacological and pharmacotherapy approaches have been proposed, investigated and recommended for the treatment of NVP. We will address the safety and effectiveness of each treatment in this review.

Nonpharmacological approaches

Lifestyle

Many women experience a heightened sense of smell and metallic taste that appears to aggravate NVP symptoms resulting in aversions to different types of food that they otherwise regularly eat and enjoy. It has been hypothesized that this new aversion to certain types of foods, especially strong tasting vegetables and, in particular, meats and poultry, is a protective mechanism of NVP, by causing the mother to avoid potentially toxic or bacteria-containing foods.21

The Motherisk NVP line at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children has been counseling women on the management of NVP for more than 15 years. We have developed the following dietary guidelines, which have been followed by many clinicians.

Maintain adequate hydration and electrolyte levels; drinking at least 2 liters of water a day.2

Avoid an empty stomach at all times, with small frequent meals every 1–2 hours, consisting of bland foods throughout the day.2,9,19

Prevent a full stomach (ie, not mixing solids with liquid; avoiding large meals and very fatty food).2

Avoid strong tasting, odorous foods (ie, spicy, metallic tastes).2,9,19

Snack on nuts and high protein foods between meals.22

Discontinue iron-containing prenatal multivitamins in early pregnancy,2,9 and switch to children’s chewable tablets and folic acid instead. Resume iron-containing prenatal vitamins after 12 weeks when iron is most needed by mother and baby. Pregnant women with past or current anemia should not discontinue prenatal vitamins, but may take them in divided doses.

Consume ice chips, popsicles, and very cold beverages to help reduce metallic taste.

Eat simple dry carbohydrates (ie, crackers, biscuits, etc) prior to getting out of bed in the morning.

Implementing uniform dietary changes can be quite challenging; consequently randomized controlled trials to investigate the effectiveness of dietary changes are lacking. Surveys conducted with women with NVP, especially HG patients, do report moderate relief with these dietary changes.23–25 One recent study also reported that women who have higher protein portions in their diet experience less severe NVP.22,26

Other recommendations include shortening food preparation time, allowing food to digest before lying down, eating more of the foods that are appealing, eating in a place that is comfortable, avoiding warm odorous places, drinking half an hour before or after but not during meals, drinking a cup of herbal tea with honey (eg, peppermint or chamomile) and wearing comfortable clothes.27 It has also been shown that brushing teeth after a meal, drinking peppermint tea, or sucking on peppermint candy, can ameliorate postprandial nausea.27

In addition to a healthy non-NVP provoking diet, it is also important to receive adequate amounts of sleep, as fatigue can aggravate NVP symptoms.19 This includes 8 hours of sleep at night, and taking time off work to rest when experiencing NVP.

Acupressure

Acupressure is a complementary medicine technique closely related to acupuncture, consisting of certain pressure points in the body, where pressure is applied by finger, hand, elbow, or stimulated by electric devices. Pericardium 6 (P6) also known as point Neiguan, is an acupoint located about three fingers or 4.5 cm above the wrist on the inside of the forearm.28 According to Chinese medicine, P6 is considered the key point in relieving nausea and vomiting symptoms. Applying direct pressure or wearing wrist bands (ie, Sea Bands) may also alleviate symptoms. Several studies looking at the efficacy of wrist bands and electrical stimulation of P6 have documented conflicting results; although most do report some initial relief, up to 50%, when compared with control groups.9,19,28 Although relief of symptoms has been associated with a placebo effect, a recent study with placebo and control groups did find a greater degree of relief in the treatment group; although the difference was not significant.9,28 Despite weak evidence of efficacy, acupressure is a safe, inexpensive, and noninvasive way to help reduce symptoms of nausea for some women and can be considered as a first option when trying to manage NVP symptoms.

Ginger

Ginger (Zingiber officinale), primarily grown in Asia and tropical areas, belongs to the family of plants that include cardamom and turmeric.29 The rhizome, the edible part of the ginger (often incorrectly referred to as the ginger root), has been used since ancient times for the treatment of a variety of medical conditions. A number of recently conducted studies have focused on the antiemetic effect of ginger, including treatment of NVP.29 Four of six randomized controlled trial studies prior to 2005 demonstrated the effectiveness of ginger in treating pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting, with results that were superior to placebo. Two reported effectiveness comparable to vitamin B6, which has also proven to be effective in treating nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.29

There are multiple preparations of ginger; either in the form of spice in foods and drinks, or extracts in teas and capsules. 19 Randomized controlled trial studies have used different formulations of root powder, capsule, or extract in dosages of 250 mg up to 1000 mg/day (root powder equivalent); and it has been shown that there is a significant reduction in the number of episodes of vomiting as well as severity and duration of nausea in women on this regimen.9,29,30 One recent study reported that ginger is superior to vitamin B6 in decreasing the severity of nausea.31 In addition, a 1000 mg/day dosage was effective without any negative pregnancy outcomes, so dosages of 1000 mg or lower per day can be used without safety concerns. Adverse impacts may include mild gastrointestinal effects such as heartburn, diarrhea, and mouth irritation, but these are generally uncommon.29

In summary, it appears that ginger is a safe, effective, and inexpensive solution for treating NVP and should be considered as a first-line option for management of NVP symptoms, or as adjuvant with other forms of therapy.

Pharmacological approaches

Pyridoxine/vitamin B6

B6 is a water soluble vitamin that is an essential coenzyme for the metabolism of amino acids, lipids, and carbohydrates. Pyridoxine or vitamin B6 has been studied extensively for its antiemetic property. Two randomized controlled studies reported that vitamin B6 significantly reduced the severity of NVP symptoms in women with moderate or severe nausea and vomiting, when compared with placebo.32,33 Although no relationship has been found between B6 status and the incidence of morning sickness, using 10–40 mg/day appears to reduce the severity of NVP symptoms.32,33 Its effectiveness for reducing the severity of NVP has been used as a parameter in several studies to compare the effectiveness of ginger in reducing NVP symptoms with ginger appearing superior to B6.30,34,35 The B6 dose can be adjusted according to maternal weight and severity of NVP, and maternal doses of up to 500 mg/day can be used without increasing maternal adverse effect or jeopardizing fetal safety.35 However, a dose of up to 200 mg/day, as suggested in the 2007 Motherisk NVP algorithm, is the current recommended high dose. Concerns about maternal toxicity have been reported with dosages much higher than 500 mg/day, and in the 2000–6000 mg/day range.35

Doxylamine/pyridoxine combination

The delayed release formulation of doxylamine and pyridoxine combination, known as Bendectin® in the United States and Debendox® in the United Kingdom, was available and widely prescribed to pregnant women with NVP from 1958–1983.9,19,36 In 1983 the manufacturer voluntarily removed the drug from the market due to litigations and false allegations regarding teratogenic effects. Consequently, there was a 2–3-fold increase in the rate of hospitalization due to NVP.9,35,36 Many case control and cohort studies, with over 170,000 exposures have demonstrated the safety of the combination of doxylamine and pyridoxine, and although it is no longer commercially available in the United States, many compounding pharmacies will prepare the combination on request.7 Women will also take a combination of doxylamine succinate (ie, Unisom®) and a vitamin B6 tablet for the same effect. In Canada, the combination is marketed as Diclectin®, and is considered the first line drug therapy for the treatment of NVP.35,36

Diclectin® contains 10 mg doxylamine succinate and 10 mg pyridoxine HCL in a delayed-release formulation; doxylamine is an antihistamine that blocks H1 receptors, and the safety of H1 antagonist antihistamines have been demonstrated in over 200,000 first trimester exposures.35–37 The standard dose of Diclectin® is 4 tablets/day and is recommended to be taken as 2 tablets at bedtime, 1 in the morning and 1 in the afternoon. The delayed-release formulation ensures the availability of the drug in the morning when it’s taken at night, in the afternoon when taken in the morning, and in the evening when taken in the afternoon.36 It may take several days to experience the full effect of the medication, and women should not discontinue therapy or be discouraged if they don’t find immediate relief. The standard dosage can be adjusted based on severity of NVP and maternal weight. The safety of higher doses of up to 12 tablets per day has been demonstrated without increasing adverse effects, or fetal risk; side effects of tiredness, drowsiness and sleepiness, as well as birth defects and birth weight, were not increased with supra doses of Diclectin®.35,36

As the only drug approved for use in pregnancy, Diclectin® should be used as first-line therapy for the treatment of NVP symptoms in women, as studies have shown a 70% decrease in nausea and vomiting with its use.9

Antihistamines

Other H1-blocker antihistamines such as dimenhydrinate (Gravol®) and diphenhydramine (Benadryl®), have been used for NVP treatment without safety concerns. Exposure of more than 200,000 first trimester women from 24 different studies, failed to show any increase in the baseline risk of 1%–3% for birth defects; in fact it was found that these women had a slightly lower risk for malformations.38 Pooled data from several different studies have documented the effectiveness of a variety of H1 blocker antagonists in reducing nausea and vomiting symptoms.38 Other H1 blocker antihistamines that have been used in pregnancy include buclyzine, cyclizine, hydroxyzine, and meclizine. The availability of some of these antihistamines (ie, cyclizine) in suppository or parenteral formulation, makes them appropriate choices for the treatment of acute or breakthrough NVP.36

Dopamine antagonists

Phenothiazines

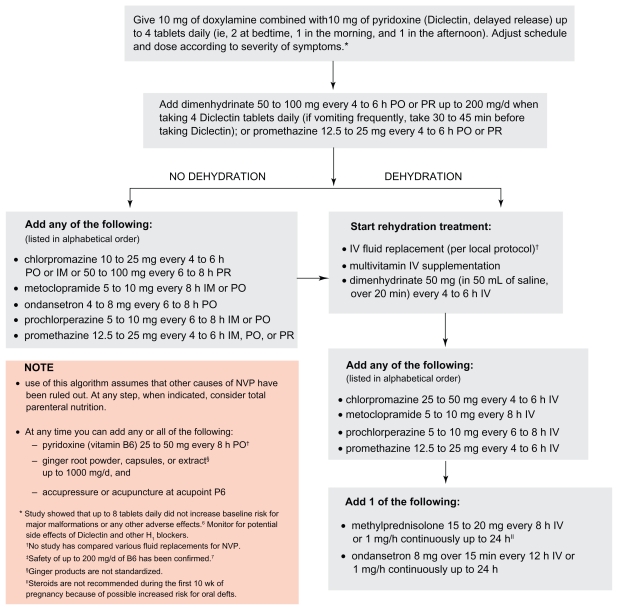

Phenothiazines such as chlorpromazine, perphenazine, prochlorperazine, promethazine, and trifluoperzaine, have shown to be superior to placebo in the treatment of severe NVP.36,38,39 The aggregate of data has failed to find an increase for adverse effects in babies whose mothers took phenothiazines during pregnancy.38 Thus, they may be implemented in the regimen for management of NVP when other antiemetics are unavailable or have not been effective (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pharmacological treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: if no improvement, proceed to next step.

Abbreviations: IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NVP, nausea and vomiting of pregnancy; PO, by mouth; PR, by rectum.

Metoclopramide

Metoclopramide is an upper gastrointestinal motility stimulant and has been used in clinical practice for the treatment of NVP.36 In Canada, with the availability of Diclectin®, metoclopramide use is reserved for more severe cases of NVP. However, in some European countries and Israel it has been the drug of choice for treatment of NVP for decades, despite the lack of evidence for safety in pregnancy.40 In recent years, a few small studies conferred safety;36 however, the largest study to date was published in 2009, with more than 3400 1st trimester exposures and there was no increased risk for major malformations.40 Subcutaneous metoclopramide is effective in many women with NVP and HG.41 These findings are reassuring, especially for women who experience excessive sleepiness from the doxylamine in Diclectin®, which can be quite disruptive for some.40,41 Side effects with metoclopramide therapy include akathesia and other extrapyramidal symptoms, which are generally quite minor, and dependent on dose and duration of treatment.38

5-HT3 antagonist

Ondansetron is effective in treating nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, which lead to its increased use in treating nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.9 It is the most commonly used 5-HT3 antagonist for the treatment of severe NVP, usually when other types of therapy prove ineffective. A limited number of case series and one study from Motherisk which included 176 women exposed to ondansetron in the 1st trimester, failed to find an association between exposure in first trimester and increased risk for major malformations.38,42,43 Although it may help with reducing symptoms, IV ondansetron was not found to be more effective than promethazine.36,38 Because of cost and paucity of data regarding use in pregnancy, this drug should be reserved for when other forms of therapy prove ineffective.

Others

Anticholinergics

Dicyclomine and scopolamine have been used in the nonpregnant population for the treatment of nausea and vomiting. Pregnancy exposures have not shown an increase in baseline risk for malformations with either drug.38 Effectiveness studies for scopolamine are lacking, and the existing evidence for dicylomine fail to show improvement in NVP symptoms.38 Using either drug for NVP is not recommended as a first choice; scopolamine, available as transdermal patches, is a good option if the patient has trouble swallowing tablets or dislikes using suppositories.

Corticosteroids (dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, etc)

Corticosteroids have successfully been used for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Their use in pregnancy, however, has been associated with a small but significant increase in the incidence of oral cleft in a study published by Motherisk.44 A number of reports have shown successful use for treatment of HG, although the pooled data failed to show superiority to placebo or promethazine in the treatment of NVP.38 Due to the small risk for oral cleft, the use of corticosteroids should be reserved for treatment when other drugs have been ineffective and only following 10 weeks gestation as per the Motherisk NVP algorithm (Figure 1).

Acid reflux/heartburn pharmacotherapy

Gastrointestinal reflux disorders are common medical conditions in pregnancy, with up to 85% of pregnant women experiencing some or all symptoms associated with dyspepsia, which include heartburn/acid reflux (HB/RF), regurgitation, belching, flatulence, stomach bloating, indigestion, and sensation of a lump in the back of the throat; over 50% have shown to experience HB/RF in first trimester.45 One recent prospective study demonstrated an increase in severity of NVP symptoms in the presence of HB and/or RF; it was also noted that women who experience both tend to classify their NVP as severe, compared with women who were experiencing just one or neither HB/RF.46 With exacerbation of NVP symptoms due to HB/RF, the use of acid-reducing agents will provide relief for many women. Acid-reducing pharmacotherapy includes the use of antacids, H2-histamine blockers, and proton pump inhibitors, all of which have been studied quite extensively in pregnancy, with proven safety.46–48 The effective treatment of HB/RF with these drugs has corresponded with a significant decrease in the severity of NVP symptoms experienced by women and a significant increase in wellbeing. 46 Thus the treatment of HB/RF symptoms with acid reducing agents, in conjunction with other antiemetics, should be encouraged as part of standard NVP management. Prior to treatment of HB/RF symptoms, patients with severe NVP should be tested for the presence of helicobacter pylori infection, which has been associated with hyperemesis gravidarum and increased severity of gastrointestinal conditions.11,48

Rehydration/enteral or parenteral nutrition

When persistent weight loss and/or dehydration is present despite antiemetic therapy, as usually observed with HG patients, serious complications may arise if the patient is not treated. Intravenous rehydration must be used for women who cannot tolerate liquids or show clinical signs of dehydration; vitamins and electrolytes should be replenished, and ketosis should be corrected in these patients.9,36 When vomiting is prolonged, dextrose, vitamins, especially thiamine, should be included in the therapy.9

Women who continue to lose weight and cannot tolerate food, should be considered for enteral tube feeding first, prior to considering parenteral feeding, as this condition has been associated with life-threatening complications.49 A recent study involving refractory hyperemesis in a small group of women reported a clear reduction in the extent of vomiting and a complete cessation, 2–5 days respectively, after tube insertion; weight gain was observed in some women who stayed on tube feeding for more than 4 days.50

Peripheral parenteral nutrition, using a central catheter inserted peripherally, containing high lipid formulation, is used in patients who do not require a high caloric intake and whose treatment length is short term.9,51 The use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) has been employed for women with life-threatening cases of HG with zero tolerance for any food intake, in order to provide adequate maternal nutrition and continued fetal growth. Due to the high risk associated with TPN – thrombosis, metabolic disturbances, and infectious complications – it should be used as a last resort, when all other modalities have failed.50 With carbohydrate rich TPN, thiamine supplementation as a prophylactic measure against Wernicke’s encephalopathy is extremely important.50

Conclusion

The physical and psychological morbidity associated with NVP is a major deterrent of wellbeing for many women, with marked negative impact on their pregnancy experience.52,53 Fortunately, evidence-based information in the literature does exist, making the management of NVP medically possible. Prior to starting pharmacological therapy, women should try the appropriate dietary changes and incorporate the use of ginger and vitamin B6, which may eliminate the need for further intervention. If these treatments are not effective, pharmacotherapy should be started as all the drugs used in the treatment for NVP appear to be safe for the fetus and have some degree of effectiveness.

Treatment with pharmacotherapy should follow the stepwise guide in Figure 1; the treatments outlined are listed in alphabetical order and it is the physician’s decision to decide which order is most appropriate according to their patient’s condition. The use of antiemetics should begin with Diclectin® or any doxylamine/pyridoxine combination, as the largest body of evidence exists for their efficacy and safety. Other antiemetics can be implemented according to the algorithm if symptoms don’t resolve. Concurrent treatment of HB and RF, using antacids, H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors, is also encouraged.45,46 These techniques should only be implemented when other causes of nausea and vomiting have been ruled out (Table 1). Treatment of these underlying conditions can bring relief to women and eliminate the need for any further treatment.

Health care providers should recognize NPV as a medical condition with significant potential to compromise women’s wellbeing, even when symptoms are moderate, and should not hesitate to treat aggressively. Dismissing NVP as an inconsequential part of pregnancy, and not providing adequate treatment, can seriously compromise the health of both mother and fetus. The attitude and practices of physicians and other health care providers is integral in the management of this debilitating condition.54

Acknowledgment

The Motherisk NVP Helpline is supported by Duchesnay, Laval, Quebec, Canada. Neda Ebrahimi has received Graduate Student Funding supported by Duchesney.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead AM, Jagger C. A prospective study of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43(371):245–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einarson A, Maltepe C, Boskovic R, Koren G. Treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: an updated algorithm. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(12):2109–2111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigel MM, Weigel RM. Nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. An epidemiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96(11):1304–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch KL, Frissora CL. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32(1):201–234. vi. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(02)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin TM. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;41(3):597–605. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199809000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linseth G, Vari P. Nausea and vomiting in late pregnancy. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(5):372–386. doi: 10.1080/07399330590933926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broussard CN, Richter JE. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27(1):123–151. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verberg MF, Gillott DJ, Al-Fardan N, Grudzinskas JG. Hyperemesis gravidarum, a literature review. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(5):527–539. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) Practice Bulletin: nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):803–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asker C, Norstedt Wikner B, Kallen B. Use of antiemetic drugs during pregnancy in Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(12):899–906. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandven I, Abdelnoor M, Nesheim BI, Melby KK. Helicobacter pylori infection and hyperemesis gravidarum: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(11):1190–1200. doi: 10.3109/00016340903284927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Q, O’Brien B, Relyea J. Severity of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: what does it predict? Birth. 1999;26(2):108–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan RL, Olshan AF, Savitz DA, et al. Maternal influences on nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2009 Dec 11; doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0548-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith C, Crowther C, Beilby J, Dandeaux J. The impact of nausea and vomitting on women: a burden of early pregnancy. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40(4):397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2000.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poursharif B, Korst LM, Fejzo MS, MacGibbon KW, Romero R, Goodwin TM. The psychosocial burden of hyperemesis gravidarum. J Perinatol. 2008;28(3):176–181. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munch S. Women’s experiences with a pregnancy complication: causal explanations of hyperemesis gravidarum. Soc Work Health Care. 2002;36(1):59–76. doi: 10.1300/J010v36n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locock L, Alexander J, Rozmovits L. Women’s responses to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Midwifery. 2008;24(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fejzo MS, Poursharif B, Korst LM, et al. Symptoms and pregnancy outcomes associated with extreme weight loss among women with hyperemesis gravidarum. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(12):1981–1987. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsenault MY, Lane CA, MacKinnon CJ, et al. The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24(10):817–831. quiz 832–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poursharif B, Korst LM, Macgibbon KW, Fejzo MS, Romero R, Goodwin TM. Elective pregnancy termination in a large cohort of women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Contraception. 2007;76(6):451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaxman SM, Sherman PW. Morning sickness: a mechanism for protecting mother and embryo. Q Rev Biol. 2000;75(2):113–148. doi: 10.1086/393377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jednak MA, Shadigian EM, Kim MS, et al. Protein meals reduce nausea and gastric slow wave dysrhythmic activity in first trimester pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(4 Pt 1):G855–G861. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.4.G855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodwin TM, Poursharif B, Korst LM, MacGibbon KW, Romero R, Fejzo MS. Secular trends in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(3):141–147. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King TL, Murphy PA. Evidence-based approaches to managing nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(6):430–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandra K, Magee L, Einarson A, Koren G. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: results of a survey that identified interventions used by women to alleviate their symptoms. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;24(2):71–75. doi: 10.3109/01674820309042804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latva-Pukkila U, Isolauri E, Laitinen K. Dietary and clinical impacts of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23(1):69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bischoff SC, Renzer C. Nausea and nutrition. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129(1–2):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Can Gurkan O, Arslan H. Effect of acupressure on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White B. Ginger: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(11):1689–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ensiyeh J, Sakineh MA. Comparing ginger and vitamin B6 for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Midwifery. 2009;25(6):649–653. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozgoli G, Goli M, Simbar M. Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(3):243–246. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahakian V, Rouse D, Sipes S, Rose N, Niebyl J. Vitamin B6 is effective therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(1):33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vutyavanich T, Wongtra-Ngan S, Ruangsri R. Pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(3 Pt 1):881–884. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sripramote M, Lekhyananda N. A randomized comparison of ginger and vitamin B6 in the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86(9):846–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shrim A, Boskovic R, Maltepe C, Navios Y, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome following use of large doses of vitamin B6 in the first trimester. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(8):749–751. doi: 10.1080/01443610600955826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atanackovic G, Navioz Y, Moretti ME, Koren G. The safety of higher than standard dose of doxylamine-pyridoxine (Diclectin) for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41(8):842–845. doi: 10.1177/00912700122010735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seto A, Einarson T, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome following first trimester exposure to antihistamines: meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14(3):119–124. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magee LA, Mazzotta P, Koren G. Evidence-based view of safety and effectiveness of pharmacologic therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl Understanding):S256–S261. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishai R, Mazzotta P, Atanackovic G, et al. Critical appraisal of drug therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: II. efficacy and safety of Diclectin (doxylamine-B6) Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;7(3):138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matok I, Gorodischer R, Koren G, Sheiner E, Wiznitzer A, Levy A. The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2528–2535. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lombardi DG, Istwan NB, Rhea DJ, O’Brien JM, Barton JR. Measuring outpatient outcomes of emesis and nausea management in pregnant women. Manag Care. 2004;13(11):48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazzotta P, Magee LA. A risk-benefit assessment of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Drugs. 2000;59(4):781–800. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Einarson A, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, Kennedy D, Tan MP, Koren G. The safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. BJOG. 2004;111(9):940–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park-Wyllie L, Mazzotta P, Pastuszak A, et al. Birth defects after maternal exposure to corticosteroids: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Teratology. 2000;62(6):385–392. doi: 10.1002/1096-9926(200012)62:6<385::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill SK, Maltepe C, Koren G. The effect of heartburn and acid reflux on the severity of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23(4):270–272. doi: 10.1155/2009/678514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gill SK, Maltepe C, Mastali K, Koren G. The effect of acid-reducing pharmacotherapy on the severity of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2009;2009:585269. doi: 10.1155/2009/585269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gill SK, O’Brien L, Koren G. The safety of histamine 2 (H2) blockers in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(9):1835–1838. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gill SK, O’Brien L, Einarson TR, Koren G. The safety of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1541–1545. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.122. quiz 1540–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russo-Stieglitz KE, Levine AB, Wagner BA, Armenti VT. Pregnancy outcome in patients requiring parenteral nutrition. J Matern Fetal Med. 1999;8(4):164–167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199907/08)8:4<164::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ismail SK, Kenny L. Review on hyperemesis gravidarum. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21(5):755–769. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogura JM, Francois KE, Perlow JH, Elliott JP. Complications associated with peripherally inserted central catheter use during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5):1223–1225. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chou FH, Chen CH, Kuo SH, Tzeng YL. Experience of Taiwanese women living with nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51(5):370–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swallow BL, Lindow SW, Masson EA, Hay DM. Psychological health in early pregnancy: relationship with nausea and vomiting. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24(1):28–32. doi: 10.1080/01443610310001620251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Munch S. A qualitative analysis of physician humanism: women’s experience with hyperemesis gravidarum. J Perinatol. 2000;20(8 Pt 1):540–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]