Abstract

Cancers are highly heterogeneous and contain many passenger and driver mutations. To functionally identify tumor suppressor genes relevant to human cancer, we compiled pools of short harpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting the mouse orthologs of genes recurrently deleted in a series of human hepatocellular carcinomas, and tested their ability to promote tumorigenesis in a mosaic mouse model. In contrast to randomly selected shRNA pools, many deletion-specific pools accelerated hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Through further analysis, we identified and validated 13 tumor suppressor genes, 12 of which had not been linked to cancer before. One gene, XPO4, encodes a nuclear export protein whose substrate EIF5A2 is amplified in human tumors, is required for proliferation of XPO4-deficient tumor cells, and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Our results establish the feasibility of in vivo RNAi screens and illustrate how combining cancer genomics, RNA interference, and mosaic mouse models can facilitate the functional annotation of the cancer genome.

Introduction

Diversity and complexity are hallmarks of cancer genomes. Even tumors arising from the same cell type or tissue harbor a range of genetic lesions that facilitate their uncontrolled expansion and eventual metastasis. As a consequence, the behavior of individual tumors – how they progress and ultimately respond to therapy – is heterogeneous and unpredictable. To date, many cancer genes have been identified, and through characterizing their action new treatment strategies have been established. It follows that a further understanding of cancer genetics will improve cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy.

Recent technological advances have greatly increased the resolution and depth at which cancer cell genomes can be examined, making it possible to envision the cataloging of every gene whose mutation or alteration occurs in human tumors (Gomase et al., 2008). For example, regions of copy number alteration can be identified by high resolution array-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH); in many cases, regions of chromosomal amplification harbor oncogenes whereas deleted regions harbor tumor suppressor genes (Chin and Gray, 2008). In addition, somatic point mutations potentially selected for during tumor evolution can be identified by high throughput sequencing (Wood et al., 2007; Greenman et al., 2007). However, owing to the inherent genomic instability of cancer cells, gene linkage, and spontaneous mutagenesis, cancers also contain somatically acquired “passenger” mutations that may not confer a selective advantage to the developing tumor. Moreover, some genes are haploinsufficient tumor suppressors such that loss of even one allele can promote tumorigenesis – even without a corresponding mutation in the remaining wild-type allele – making it difficult to pinpoint relevant tumor suppressors in large deletions. Therefore, candidate genes identified through genomic approaches require functional validation before they are useful for clinical applications.

Functional characterization of cancer genes is often tedious, and it is not always obvious which assays will reveal the putative oncogenic activity of relatively uncharacterized genes. Moreover, although cell culture systems are tractable, in vitro models do not recapitulate all features of the tumor microenvironment and so do not survey all relevant gene activities. Currently, a “gold-standard” approach for studying candidate oncogenes and tumor suppressors involves the production of transgenic and knockout mice that contain germline alterations in the candidate oncogenic lesion (Van Dyke and Jacks, 2002). These strains have proven invaluable for validating cancer genes and create powerful models for subsequent studies. Nevertheless, their generation and analysis is time consuming and expensive.

To facilitate a more rapid and cost-effective analysis of cancer gene action in vivo, we developed a “mosaic” mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma (Zender et al., 2006), a common but understudied cancer for which there are few treatment options (Lee and Thorgeirsson, 2006; Teufel et al., 2007). In our mouse model, hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) with different oncogenic lesions can be rapidly produced by genetic manipulation of cultured embryonic liver progenitor cells (hepatoblasts) followed by their retransplantation into the livers of recipient mice (Zender et al., 2006; Zender et al., 2005). We have previously used this model to characterize the gene products contained in the 11q22 amplicon observed in human tumors, and showed that both YAP1 and cIAP1 cooperate to promote tumorigenesis in particular genetic contexts (Zender et al., 2006).

To further accelerate the study of cancer genes in vivo, our laboratory has adapted stable RNA interference technology to down-regulate tumor suppressor genes in mice (Hemann et al., 2003). We utilize microRNA-based short hairpin RNAs (shRNAmir, hereafter referred to as shRNAs) that are potent triggers of the RNAi machinery and can efficiently suppress gene expression when expressed from a single genomic copy (Dickins et al., 2005; Silva et al., 2005). We previously used this technology in our mosaic mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma to show that stable knockdown of the p53 tumor suppressor by RNAi can mimic p53 gene loss in vivo (Zender et al., 2005), and that regulated RNAi can reversibly modulate endogenous p53 expression to implicate the role of p53 loss in tumor maintenance (Xue et al., 2007). We also used similar approaches to rapidly validate Deleted in Liver Cancer 1 (DLC1) as a potent tumor suppressor gene (Xue et al., 2008).

The goal of this study was to integrate cancer genomics, RNAi technology, and mouse models to rapidly discover and validate cancer genes. Our approach was based on the premise that genomic deletions occurring in human tumors should be enriched for tumor suppressor genes. We therefore produced a focused shRNA library targeting the mouse orthologs of genes deleted in human hepatocelluar carcinoma, and screened this for shRNAs that would promote tumorigenesis in our mosaic model of HCC. Our approach proved to be highly effective, resulting in the functional validation of 13 tumor suppressor genes. In addition to identifying new genes and pathways relevant to liver cancer and other tumor types, our study provides one blueprint for functionally annotating the cancer genome.

Results

Oncogenomic studies of human hepatocellular carcinoma

Tumor suppressor gene inactivation is often due to homozygous or hemizygous chromosomal deletions. To identify genomic regions potentially containing tumor suppressor genes, we analyzed ~100 human hepatocellular carcinomas of different etiologies (Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C or ethyltoxic liver cirrhosis) for DNA copy number alterations using representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis (ROMA), a high-resolution array-based CGH platform (Lucito et al., 2003). Raw data was converted into segmented profiles (Hicks et al., 2006) and segments that showed significant decrease from the ground state were identified (Figure 1A). We then computationally estimated genetic events so that a homozygous deletion within a heterozygous deletion would be scored as two deletion events rather than one (Krasnitz et al., in preparation), and plotted the resulting deletion event frequency across the entire genome (Figure 1B). Among the many deletions detected, only a fraction were <5MB. We hypothesized that these focal deletions were most likely to be enriched for tumor suppressor genes.

Figure 1. ROMA deletion based RNA interference library.

(A) A representative whole genome ROMA array CGH plot of a human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Arrow denotes the focal deletion highlighted in (C).

(B) Deletion counts in ROMA profiles of 98 human HCC. The points in the vicinity of 58 focal deletions (containing 362 genes) are highlighted by red circles. Dashed lines denote chromosome boundaries.

(C) A representative 524Kb focal deletion on chromosome 12 contains 10 genes.

To develop an initial gene list for further studies, we identified all of the genes embedded in recurrent focal deletions or in unique focal deletions whose gene content was also contained in broader deletions that were recurrent. Based on these criteria, we identified 58 deletions ranging in size from 98kb to 2.6Mb, containing 1 to 46 genes, respectively (see, for example, Figure 1C). Of the 362 annotated genes identified in total (Table S1, see red circles in Figure 1B), we were able to bioinformatically identify 301 mouse orthologs. We next obtained all 631 of the mir30-based shRNAs from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory RNAi CODEX library. Thus, on average, each deleted gene was represented by ~2 murine shRNAs (see workflow in Figure S1A).

Constructing an in vivo RNAi screen

We recently developed a “mosaic” mouse model where liver carcinomas can be rapidly produced by genetic manipulation of liver progenitor cells followed by their retransplantation into recipient mice (Zender et al., 2006). Since systemic delivery of RNAi currently does not enable efficient and stable knockdown of genes in tissues, we decided to introduce pools of shRNAs into premalignant progenitor cells and select for those that promote tumor formation following transplantation. We previously generated immortalized lines of embryonic hepatocytes lacking p53 and overexpressing Myc that were not tumorigenic in vivo (Zender et al., 2005); since >40% of all human HCCs are overexpressing MYC and many harbor p53 mutations or deletions (Teufel et al., 2007), we reasoned that these cells would provide a “sensitized” background where a single additional lesion might trigger tumorigenesis (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Setup of in vivo RNA interference screening.

(A) Schematic representation of the approach. ED=18 p53−/− liver progenitor cells are immortalized by transduction with a Myc expressing retrovirus. Subsequently, the cells are infected with single shRNAs or shRNA library pools and injected into the liver or subcutaneously to allow tumor formation.

(B) Growth curve of tumors derived from p53−/−;Myc cells infected with a control shRNA or three Apc shRNAs. Values are average of 6 tumors. The inset shows knockdown of Apc protein assayed by western blot.

(C) Bioluminescence imaging of tumors derived from p53−/−;Myc cells infected with a control shRNA or Apc shRNA and transplanted into the livers of immunocompromised recipient mice (n=4). Animals were imaged 40 days post surgery.

(D) H&E and β-catenin staining of liver tumors in (C). Normal liver served as control.

(E) Tumor growth curve of p53−/−;Myc cells infected with control shRNA (control), Apc shRNA (shAPC), a 1:50 diluted Apc shRNA (shAPC 1:50), Axin shRNA and a shRNA library pool (pool A7EH, taken from the Cancer1000 library).

We hypothesized that shRNAs targeting negative regulators of WNT signaling would provide positive controls to model or “reconstruct” our screen, as this pathway deregulated in a significant percentage (30–40%) of human hepatocellular carcinomas due to activating mutations in β-catenin or inactivating mutations/promoter hypermethylation of the AXIN and APC tumor suppressors (Teufel et al., 2007). We therefore introduced mir30-design shRNAs targeting Axin or Apc into p53−/−;Myc hepatocytes, and transplanted the resulting cell populations subcutaneously into nude mice or into the liver by intrasplenic injection (Zender et al., 2006; Zender et al., 2005). Of note, all of the shRNAs used in this study were cloned into pLMS, a vector optimized for in vivo use, which co-expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Dickins et al., 2005). Furthermore, the Myc transgene co-expresses a luciferase reporter to facilitate monitoring tumors using bioluminescence.

While a negative control shRNA (targeting human RB1 but not mouse) did not trigger tumor growth, the positive control shRNAs targeting Axin or Apc gave rise to tumors within 1–2 months both subcutaneously and in situ (Figure 2A–D). The resulting tumors were classified as aggressive solid, sometimes pseudoglandular, hepatocellular carcinomas (Figure 2D, top panel). They also displayed high levels of nuclear β-catenin by immunohistochemistry, indicating that the shRNAs were deregulating the predicted biochemical pathway (Figure 2D, bottom panel).

In order to determine the complexity of shRNA pools that could be screened, we tested one Apc shRNA for its ability to accelerate tumorigenesis when diluted 1:10 to 1:100. In addition, we tested a pool of 48 shRNAs targeting various murine genes that also contained two distinct Apc shRNAs. In both situations, the diluted shRNAs produced tumors rapidly, albeit with a delay relative to the pure Apc shRNA (Figure 2E). Moreover, sequencing of PCR-amplified shRNAs obtained from tumors triggered by the shRNA pool indicated that the two Apc shRNAs were enriched during tumor expansion, comprising the majority of shRNAs present in the resulting tumors (data not shown). Thus, pools of 48 shRNAs can be readily screened to identify those with tumor promoting activities similar to an Apc shRNA. Although 1:100 dilutions still enhanced tumor growth (data not shown), we concluded that screening low complexity pools was feasible and would maximize our chances of identifying weaker shRNAs that might otherwise be outcompeted by stronger ones in more complex pools.

Many shRNA pools targeting genes deleted in liver cancer promote tumorigenesis in vivo

To screen our shRNA library targeting deletion-associated genes, we pooled individual shRNAs randomly into pools of 48 and transferred them in bulk into pLMS (see also Figure S1B). Selected shRNA library pools were subjected to DNA sequencing to confirm that clone representation was maintained (data not shown). As controls, we also produced 10 pools of randomly selected shRNAs from the mouse CODEX RNAi library (i.e. not based on genomic location). Each pool, in parallel with a negative shRNA control, was introduced into p53−/−;Myc hepatocytes at a low multiplicity of infection and the resulting cell populations were transplanted subcutaneously into both flanks of four immunocompromised mice. Animals were subsequently monitored for tumor development.

The results of these experiments were striking: While mice injected with cells transduced with randomly produced shRNA pools did not develop tumors over background (Figure 3A and Figure S2A), most mice transplanted with cells harboring the deletion-focused shRNA pools developed tumors, some within 3–4 weeks (Figure 3B and Figure S2B). Many tumors appeared multifocal and all were GFP positive, indicating that the tumor cells expressed at least one shRNA. These observations validate our enrichment strategy and suggest that deletion-focused shRNA libraries are enriched for tumor promoting shRNAs.

Figure 3. In vivo shRNA library screening identifies PTEN as a potent tumor suppressor in HCC.

(A) Average volume (n=8) of tumors derived from p53−/−;Myc cells infected with a control shRNA (control) and 10 random genome-wide shRNA pools (pool size n=48).

(B) Average volume (n=8) of tumors derived from p53−/−;Myc cells infected with a control shRNA (control) and 13 ROMA deletion shRNA pools (pool size n=48). Red asterisks indicate tumors/shRNA pools subjected to subcloning and sequencing as shown in (C).

(C) Representation of the strategy to recover shRNAs from tumor genomic DNA by PCR and subcloning of the PCR products into the vector used for hairpin validation.

(D) Enrichment of two Pten shRNAs in selected tumors (right) compared to their representation in pre-injection plasmid pools (left). Pie graphs show the representation of each Pten shRNA in the total shRNA population analyzed by high-throughput sequencing.

(E) ROMA arrayCGH plot showing a focal PTEN genomic deletion in a human HCC.

(F) Validation of the same Pten shRNAs using orthotopically transplanted P53−/−;Myc cells transduced with the Pten shRNAs. Representative imaging results from 3 mice in each group are shown.

(G) shRNA mediated knockdown of Pten increases phospho-Akt. Protein lysates from p53−/−;Myc liver cells infected with Pten shRNAs (Cell) or the derived tumors (Tumor) were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin served as a loading control.

Identification of candidate tumor-promoting shRNAs

To identify shRNAs present in tumors, we isolated genomic DNA from GFP-positive tumor nodules, PCR amplified the integrated shRNAs, and cloned them into a recipient vector that could also be used for subsequent validation (Figure 3C). As a cut off criteria for further studies, we chose to isolate shRNAs from tumors that were relatively large and derived from pools that efficiently accelerated tumorigenesis (average tumor volume ≥ 0.1cm3 and ≥50% take rate). None of the random shRNA pools fit these two criteria (Figure S2C, D). The resulting plasmid pools were then sequenced to determine the representation of particular shRNAs (96 sequence reads/tumor, >3 tumors/pool). In most cases more than one shRNA was identified from each tumor nodule, suggesting the tumors were multiclonal.

Interestingly, independent shRNAs targeting Pten were highly enriched in tumors produced from cells transduced with two different shRNA pools (Figure 3D). By comparing the relative representation of each Pten shRNA to that in the initial pool, we noted that Pten.932 (HP_524) was enriched from 3 to 41% during tumor expansion (Figure 3D upper panel), whereas Pten.5331 (HP_465354) went from 1% to 67% of the total sequence reads (Figure 3D, lower panel). Immunoblotting revealed that both shRNAs suppressed Pten and increased Akt phosphorylation (Figure 3G), indicating that they were biologically active. Interestingly, while shRNA Pten.932 was more potent than shRNA Pten.5331 in the preinjected cell population, the resulting tumors showed comparable levels of Pten knockdown and p-Akt (Figure 3G). Apparently, cells with optimal knockdown are selected from polyclonal populations during tumor expansion.

PTEN is a bona fide tumor suppressor gene that is mutated in many tumor types (Tokunaga et al., 2008) and whose deletion promotes hepatocarcinogenesis in mice (Horie et al., 2004). Accordingly, we identified several HCCs with either focal or broad chromosome 10 deletions encompassing PTEN (Figure 3E). To confirm that suppression of Pten is oncogenic in our model, we re-tested the recovered Pten shRNAs by introducing them into p53−/−;Myc hepatocytes and testing their ability to form tumors following subcutaneous or intrasplenic injection. In both contexts, Pten knockdown rapidly triggered tumor growth (Figure 3F and Figure S3), thus validating our screening strategy and providing a blueprint for testing shRNAs targeting less characterized genes.

Identification and validation of previously uncharacterized tumor suppressors

Next we systematically determined the representation of shRNAs contained within all 31 tumors (derived from 7 shRNA pools) that showed accelerated tumor growth (Figure 3B; Table S2). From a total of 2307 sequence reads, we identified 36 shRNAs that were enriched at least 2.5 fold over the predicted representation in the initial plasmid pool (~2% of total). For example, the two validated Pten shRNAs ranked the 5th and 16th respectively among the most enriched shRNAs (Table S3). Besides Pten we selected 16 shRNAs targeting 14 different genes for validation (Figure 4A–B, Table S3). These included all shRNAs that were the most abundant in at least two tumors (targeting Xpo4, Armcx2, Nrsn2, Zbbx), all shRNAs for which a second shRNA against the same gene was recovered (targeting Fgf6, Set, Fstl5) and a group of seven additional shRNAs that were also highly enriched (targeting Wdr49, Wdr37, Armcx1, Gjd4, Glo1, Ddx20, Btbd9). Interestingly, although one candidate target gene, SET (histone chaperone/protein phosphatase inhibitor), is associated with a rare translocation in acute myeloid leukemia (von Lindern et al., 1992), none of the other genes previously have been linked to cancer. Nevertheless, their deletion in a subset of human tumors suggests each could be a relevant tumor suppressor (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Novel tumor suppressor genes identified by in vivo RNAi screening.

(A) Representation of some scoring shRNAs in the tumors. The representation of each shRNA is ~2% in the pre-injection plasmid pools, as shown in Figure 3D.

(B) ROMA array CGH plots depicting focal genomic deletions of the genes in panel (A).

(C) Validation of the top scoring shRNAs in a subcutaneous tumor growth assay as described in Figure 3F (n=4). Red asterisks depict genes that were further analyzed in (D).

(D) In situ validation of at least three independent shRNAs targeting genes as depicted in panel (C). Black asterisks indicate CODEX shRNAs which were initially identified in the screen. Representative bioluminescence imaging results from 3 mice are shown.

All 16 shRNAs were individually retested using the same experimental setup employed in the initial screen. A validated Pten shRNA (Pten.5331) was used as a positive control. Many of the candidate shRNAs triggered tumor growth above background, with those targeting Xpo4 (nuclear export protein), Ddx20 (GEMIN3, RNA helicase), Gjd4 (CX40.1, putative gap junction protein), Fstl5 (Follistatin-like 5) and Nrsn2 (Neurensin 2) showing the most prominent acceleration of tumor growth (Figure 4C). Since our control shRNA never accelerated tumorigenesis, insertional mutagenesis was not solely responsible for the biological effects of our candidate shRNAs – presumably, suppression of the targeted gene was required.

To rule out the possibility that individual shRNAs might promote tumorigenesis through off target effects, we generated additional shRNAs against each candidate gene and tested them for their ability to promote hepatocarcinoma development in situ. p53−/−;Myc liver progenitor cells were transduced with each shRNA, and knockdown of the predicted target gene was confirmed by immunoblotting or quantitative RT-Q-PCR (Figure S4). The resulting cell populations were transplanted into the livers of mice by intrasplenic injection, and recipients were monitored for tumor formation using bioluminescence imaging. At least three independent shRNAs targeting each candidate accelerated tumorigenesis (Figure 4D, see also Figure S5–S6 for results from subcutaneous injections). Similar results were obtained using independent populations of p53−/−;Myc liver progenitor cells (Figure S7). Therefore, genes identified through our in vivo RNAi screen are bona fide tumor suppressors in mice.

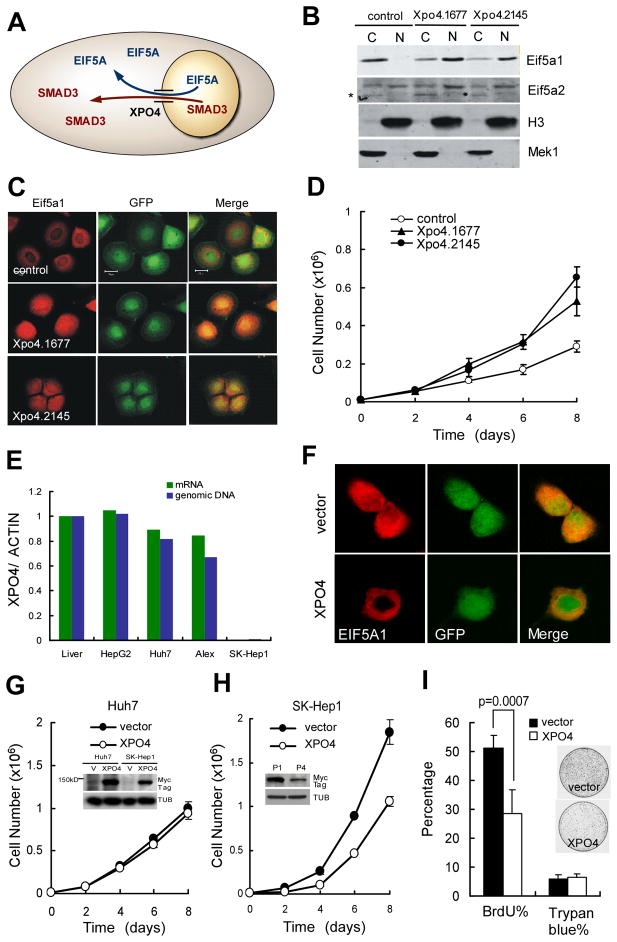

Inactivation of XPO4 deregulates SMAD3 and EIF5A signaling

The shRNA that was most enriched in our screen targets Xpo4 (Table S3). Exportin 4 belongs to the importin-β family of nuclear transporters and has two known substrates – SMAD3 and EIF5A (Figure 5A). SMAD3 is an effector of TGF-β signaling and can have pro-or anti-oncogenic effects depending on context, but whose activation is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression (Teufel et al., 2007). In response to TGF-β, SMAD3 becomes phosphorylated and shuttles to the nucleus, where it forms complexes with coactivators that transactivate TGF-β target genes (Massague, 2000). As predicted, murine hepatoma cells expressing Xpo4 shRNAs showed an increase in nuclear total and phospho-Smad3 (Figure S8A), which correlated with an increase in the levels of the TGF-β target genes Jun, Col7a1, Timp1 and p15 (Figure S8B).

Figure 5. Reintroduction of XPO4 selectively suppresses tumors with XPO4 deletion.

(A) Schematic representation of XPO4 mediated nuclear export of SMAD3 and EIF5A.

(B) Eif5a1 and Eif5a2 western blot of cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions of murine HCC cells infected with a control shRNA and two Xpo4 shRNAs. Histone 3 (H3) was used as loading control for the nuclear fraction and Mek1 for the cytoplasmic fraction. * denotes a non-specific band.

(C) Eif5a1 immunofluorescence in murine HCC cells infected with Xpo4 shRNAs.

(D) Xpo4 shRNAs promote cell proliferation in p53−/−;Myc liver cells. Error bars denote S.D. (n=2).

(E) Expression profile of XPO4 in human hepatoma cell lines. mRNA abundance and genomic DNA copy numbers of XPO4 were measured by RT-Q-PCR and genomic Q-PCR. Assays were normalized to actin and to the RNA and DNA from normal liver.

(F) Nuclear accumulation of EIF5A1 in XPO4 deficient cells is reverted by reintroduction of XPO4 cDNA. EIF5A1 immunofluorescence of human HCC cell line SK-Hep1 (XPO4 deleted) infected with control vector or XPO4 cDNA.

(G-H) Reintroduction of XPO4 cDNA into XPO4 deficient cells inhibits cell proliferation. Cell growth curves of XPO4 postive (Huh7, panel G) and XPO4 negative (SK-Hep1, panel H) human hepatoma cells infected with control vector or XPO4 cDNA. Error bars denote S.D. (n=2). Inlay in (G) indicate expression level of the 6xMyc tagged XPO4 cDNA at early passage in both cell lines. Inlay in (H) indicate XPO4 expression in passage 1 (P1) and passage 4 (P4) SK-Hep1 cells post retroviral infection and puromycin selection.

(I) Percentage of BrdU+ (proliferating) and Trypan blue+ (apoptotic) cells in SK-Hep1 cells infected with vector control or Xpo4 cDNA. Error bars denote S.D. (n=5). Inlay shows colony formation assay of SK-Hep1 cells infected with Xpo4 cDNA.

While it is straightforward to conceptualize how XPO4 might influence tumorigenesis by modulating SMAD3 function, its biological action on EIF5A is not clear. EIF5A was identified as a eukaryotic translation initiation factor and, in mammals, is encoded by two highly related genes (EIF5A1 and EIF5A2). Although in vitro studies suggest that EIF5A stimulates the formation of the first peptide bond during protein synthesis (Benne and Hershey, 1978), it may also influence nucleocytoplasmatic transport of mRNA and/or mRNA stability (Caraglia et al., 2001). As was observed for Smad3, knockdown of Xpo4 in murine hepatoma cells led to nuclear accumulation of Eif5a1 and Eif5a2 (Figure 5B–C), suggesting Xpo4 may also modulate Eif5a activity.

XPO4 selectively suppresses proliferation in human cells with an XPO4 deletion

Interestingly, Xpo4 shRNAs enhanced the proliferation of murine liver progenitor cells in vitro (Figure 5D). To extend these observations to a human system, we examined how enforced Xpo4 expression affected human HCC cell lines expressing and lacking XPO4 (see Figure 5E for a cell line, SK-Hep1, which does not express XPO4 due to a homozygous deletion). We transduced SK-Hep1 cells (XPO4 negative) and Huh7 cells (XPO4 positive) with a myc-tagged XPO4 cDNA and examined the resulting cell populations for XPO4 expression (Figure 5G inlay), EIF5A localization (Figure 5F), and proliferation (Figure 5G–I).

The exogenous XPO4 gene was expressed in both cell types, albeit at higher levels in Huh7 cells (inlays in Figure 5G). Nevertheless, while XPO4 had no impact on the in vitro proliferation of Huh7 cells (Figure 5G), it suppressed SK-Hep1 proliferation by delaying cell cycle progression (Figure 5H) without appreciably promoting apoptosis (Figure 5I). Furthermore, high XPO4 levels produced a selective disadvantage to SK-Hep1 cells, since only cells expressing low XPO4 levels could be serially passaged (Figure 5H inlay). These results extend our findings to a human system, suggest that XPO4 inactivation contributes to tumor maintenance and suggest that XPO4 can limit cell cycle progression.

XPO4 and EIF5A define a novel oncogenic signaling circuit

Although the mechanism whereby EIF5A contributes to carcinogenesis is not known, both EIF5A proteins are overexpressed in some human tumors (Clement et al., 2006), and the EIF5A2 gene is often co-amplified with PIK3CA (encoding a catalytic subunit of PI3 kinase) on chromosome 3q26 (Guan et al., 2001; Guan et al., 2004). In our dataset, we found 22 HCCs with chromosome 3 amplifications that encompass the EIF5A2 gene (Figure 6A), 3 of which exclude PIK3CA. To determine whether overexpression of EIF5A2, like XPO4 loss, is oncogenic, we retrovirally transduced an Eif5a2 cDNA into p53−/−;Myc hepatocytes and injected the cells subcutaneously into nude mice. Remarkably, Eif5a2, but not Eif5a1, efficiently triggered the growth of tumors (Figure 6B) that displayed histopathological features of hepatocellular carcinoma (data not shown).

Figure 6. EIF5A2 is a key downstream effector of XPO4 in tumor suppression.

(A) ROMA array CGH plot of a human HCC showing an EIF5A2 containing amplicon on chromosome 3.

(B) EIF5A2 expression promotes tumor formation in P53−/−;Myc liver progenitor cells. Subcutaneous tumor growth assays were performed as in Figure 2B. Error bars denote S.D. (n=4).

(C) Knockdown of EIF5A2 attenuates proliferation of human hepatoma cells harboring XPO4 deletion. Cell numbers were measured by MTT assay in human hepatoma cell lines Huh7 (wild type), Alex (EIF5A2 amplicon) and SK-Hep1 (XPO4 deletion) 48 hrs post siRNA transfection. Error bars denote S.D. (n=3).

(D) Colony formation assay of SK-Hep1 cells transfected with indicated single siRNA or combination.

To examine the requirement for XPO4 substrates in the proliferation of human tumor cells, we transfected siRNAs targeting EIF5A2 and SMAD3 into HCC cells harboring an XPO4 deletion (SK-Hep1), EIF5A2 amplification (Alex), or neither alteration (Huh7) and examined their impact on short term (MTT assay) and long term (colony formation) proliferation. Whereas each set of siRNAs efficiently suppressed their respective target (Figure S9), only siRNAs targeting EIF5A2 inhibited proliferation (Figure 6C and D), though these effects were limited to cells that amplified EIF5A2 or, more prominently, deleted XPO4 (Figure 6C). Thus, EIF5A2 is required for efficient proliferation in cells lacking XPO4 and may mediate, in part, the oncogenic effects associated with XPO4 loss. While SMAD3 may also play a role in vivo, these results establish XPO4-EIF5A2 as a regulatory circuit relevant to human cancer.

Genes identified from hepatocellular carcinoma screens may be relevant to other tumor types

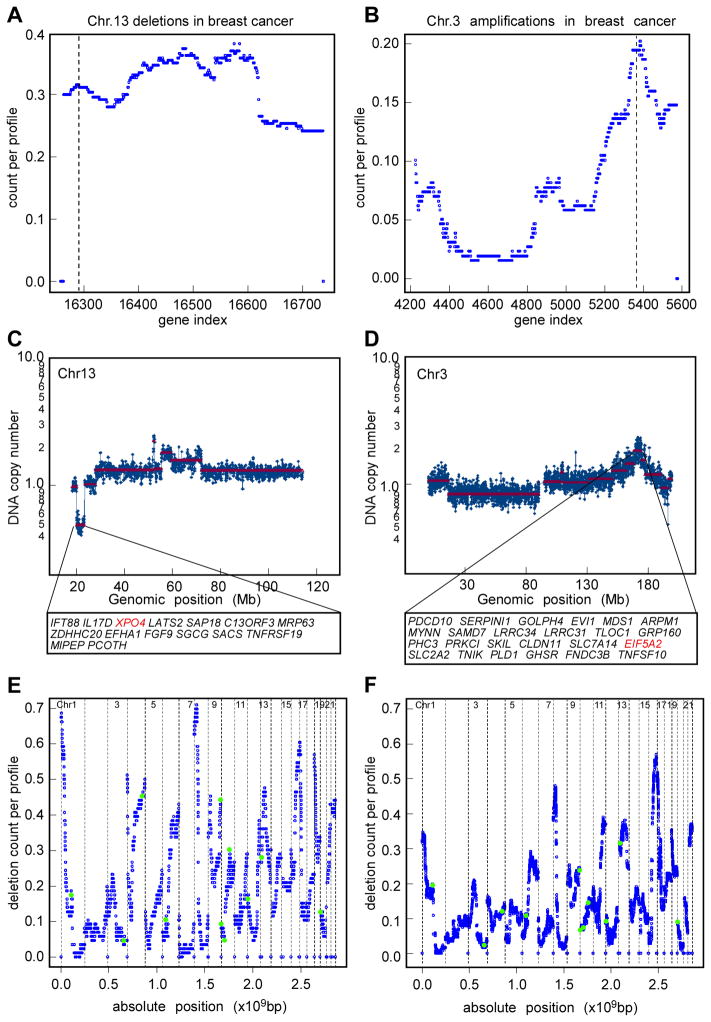

Hepatocelluar carcinoma shares common biologic and genetic features with other epithelial malignancies. Accordingly, mutations in APC and AXIN (here used as positive controls) are observed in colon carcinomas, medulloblastomas and other cancers (Segditsas and Tomlinson, 2006; Salahshor and Woodgett, 2005; Teufel et al., 2007), and PTEN (identified in our screen) loss occurs in brain, lung, colon, breast, pancreatic and prostate cancers (Chow and Baker, 2006). As a first step in expanding our analyses to other tumor types, we surveyed a database containing copy number analyses of over 257 breast cancers of various pathologies, tumor size, grade, node involvement, and hormone receptor status (Hicks et al., 2006). Gene deletion frequencies were produced from comparative genomic hybridization as described for HCC (Figure 7A); in addition, gene amplification profiles were produced in a parallel manner (Figure 7B). Remarkably, XPO4 was located at a local deletion epicenter on chromosome 13, which occurs in over 30% of tumors (Figure 7A, see example in Figure 7C) and is associated with poor survival in a large cohort of breast cancer patients (Table S5, p=0.038). Interestingly this region often also includes the Drosophila tumor suppressor LATS2 (Yabuta et al., 2000). Of note, shRNAs targeting LATS2 were not included in our screen as it was not contained in the focal deletions found in liver cancer.

Figure 7. Frequent copy number alterations of XPO4 and EIF5A2 in human breast cancer.

(A) XPO4 is frequently deleted in human breast cancer. Shown are the deletion counts in ROMA profiles of 257 human breast cancers with the genes sorted by their genomic transcription start position. Blue dots represent the deletion frequency counts for each gene on chromosome 13. The dashed line points to XPO4.

(B) EIF5A2 is frequently amplified in human breast cancer. Amplification counts (as described in A) of chromosome 3 in human breast cancer. The dashed line points to EIF5A2.

(C) ROMA plot of a 3.3Mb XPO4 deletion in a human breast cancer cell line.

(D) ROMA plot of a 5.8Mb spanning EIF5A2 amplicon in a human breast carcinoma.

(E) Genomic distribution of scoring genes from the in vivo RNAi screen. Blue dots denote the deletion frequency count (98 human HCC) for each gene in the genome. Green dots depict the 13 scoring genes (embedded in 11 focal deletions) from the HCC RNAi screen. Dashed lines represent chromosome boundaries. Note: ARMCX1/2 on the X chromosome, are not included.

(F) Tumor suppressor genes identified through the HCC in vivo RNAi screen are also frequently deleted in human breast cancer. Green circles depict the newly identified tumor suppressor genes in a deletion count frequency plot of 257 human breast cancers.

Similarly, the XPO4 substrate EIF5A2 was near the epicenter of amplifications located on human chromosome 3q26 (Figure 7B, see example in Figure 7D), which is frequently observed in breast cancer. These amplifications were often focal (see Figure 7D) but contained many additional genes. Although the PIK3CA gene is a candidate oncogene in this region, at least 3 breast cancers containing the 3q26 amplicon did not amplify PIK3CA. Together with our functional analysis, these observations suggest that EIF5A2 may be an important human oncogene [see also (Guan et al., 2004)]. Several other validated tumor suppressors identified in our HCC screen (Figure 7E) were also located in focal deletions in human breast cancer (Figure 7F), including PTEN, FGF6, NRSN2 and GLO1/BTBD9 (Table S4). Therefore, while our screen focused on hepatocellular carcinoma, the tumor suppressors we identified may be relevant to other tumor types.

Discussion

This study describes an RNAi screen for genes that affect a complex phenotype in mice (see also Bric et al., submitted). Specifically, to identify new tumor suppressor genes, we performed an oncogenomics-directed RNAi screen for shRNAs that promote tumorigenesis in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Our approach was based on the premise that chromosomal regions lost in human cancers are enriched for tumor suppressor genes and, indeed, we show that pools of shRNAs corresponding to genes deleted in human hepatocellular carcinoma frequently “score” in tumor promotion, whereas pools containing random shRNAs do not. By identifying and retesting those shRNAs that were enriched in the resulting tumors, we validated 13 genes whose suppression reproducibly promotes tumorigenesis in mice. Given that some tumor suppressors were likely missed owing to the absence of an effective shRNA in our library, this approach was remarkably efficient.

The fact that our deletion-specific RNAi pools were enriched for tumorigenic shRNAs implies that many of the genomic deletions observed in human tumors produce a selective advantage and are not “passenger” lesions coincidentally linked to oncogenesis. This notion also explains why some cancer-associated deletions occur repeatedly in different tumor types. Still, we imagine that some loci are particularly susceptible to deletion, for example, at fragile sites, and can be subject to recurrent deletions that do not confer any selective advantage (Durkin et al., 2008). Although such instability provides one explanation for why we did not identify a driving event for each deletion examined in our screen, our studies document the value of using genomic deletions as filters for identifying new tumor suppressor genes.

Surprisingly, three of the 10 focal deletions that scored in our system contain multiple genes whose knockdown accelerates tumorigenesis in mice. Moreover, XPO4 and EIF5A2 are adjacent to a strong candidate tumor suppressor (LATS2) and oncogene (PIK3CA), respectively. That some genomic regions can contain closely linked cancer genes is not unprecedented; for example, the 11q22 amplicon found in human liver cancer and other tumor types contains two genes – BIRC2 and YAP – whose overexpression can cooperate in tumorigenesis (Zender et al., 2006), the MYC amplicon on chromosome 8 often co-amplifies a non-coding RNA that contributes to cell survival (Guan et al., 2007), and the 14q13 amplicon in lung cancer contains multiple transcription factor oncogenes that cooperate in vitro (Kendall et al., 2007). Conversely, focal deletions on chromosomal region 9p21 often simultaneously co-delete the INK4a (CDKN2A, isoforms 1 & 3), INK4b (CDK2NB), and ARF (CDKN2A, isoform 4) tumor suppressor genes, which can act in combination to suppress tumorigenesis (Krimpenfort et al., 2007). The biological rationale for such genomic organization is not understood, but it is possible that these genes are co-regulated at the level of higher order chromatin organization for some purpose during normal cell proliferation or development. Interestingly, shRNAs targeting the linked tumor suppressors identified here were not as potent as others identified in the screen. Although this may be coincidental, future studies will evaluate the combined effects of suppressing these genes on tumorigenesis in mice.

The tumor suppressor genes characterized here target a remarkable array of biological activities. Genes such as AXIN (which targets the β-catenin pathway and served as a positive control) as well as PTEN (a PI3-kinase pathway regulator identified from the screen) have been implicated in liver cancer based on their somatic alteration in human tumors. Our study therefore solidifies the importance of these genes in liver cancer and develops tractable animal models that may be useful for future functional or preclinical studies. In addition, the SET gene, which encodes a histone chaperone and potential protein phosphatase inhibitor, was initially identified as part of a translocation in a human AML patient (von Lindern et al., 1992). Although SET clearly has oncogenic activity in the context of the fusion protein (von Lindern et al., 1992), our studies suggest that the native protein is a tumor suppressor.

By contrast, the vast majority of genes we identified had not previously been linked to cancer. For example, we identified an FGF (FGF6), an RNA helicase (DDX20/GEMIN3), a metabolic enzyme (GLO1), and GJD4 (CX40.1), a gap junction protein that apparently all act as tumor suppressors in vivo. Some of the genes, for example FSTL5, NRSN2 (C20ORF98), and ZBBX (FLJ23049), are as yet uncharacterized; however, we believe they are relevant to human cancer based on prior evidence for their somatic alteration in human tumors and their impact on tumorigenesis in mice. Clearly more work will be required to understand how each of these genes suppresses tumorigenesis and, given the unexpected nature of each gene, such studies may uncover new pathways or principles relevant to cancer.

Our studies utilized p53 loss and Myc as cooperating genetic lesions owing to their common occurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma, so it is likely that some of the tumor suppressors we identify are specific to this genetic configuration and that others would be identified screening in different genetic contexts. Indeed, some tumor-promoting shRNAs we identified enhance proliferation in the presence of oncogenic Ras whereas others do not (data not shown). In any case, these results greatly expand our understanding of the genetics of human hepatocelluar carcinoma and point to the potential of non-biased in vivo RNAi screens to identify potentially new and understudied areas of cancer biology.

Our top scoring candidate tumor suppressor, exportin 4, belongs to the importin-β superfamily of nuclear transporters and mediates the nuclear export of SMAD3, EIF5A1 and EIF5A2. It seems likely that XPO4 loss contributes to tumorigenesis by promoting the nuclear accumulation of key substrates. Such a possibility is not unprecedented, and indeed, deregulated signaling through the WNT and AKT pathways is thought to influence tumorigenesis by enhancing, or reducing, nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and FOXO, respectively. However, other than rare AML associated fusion proteins targeting the nuclear pore machinery (Kau et al., 2004), most previously identified mutations affect transport associated signaling pathways and not the nuclear transport machinery itself. That XPO4 deletions are relatively common suggest that this may be an important mechanism of oncogenesis.

The XPO4 substrates SMAD3 and EIF5A show activities or expression patterns consistent with a role in modulating tumorigenesis. For example, SMAD3 is a modulator of the TGF-β-pathway, which can be anti-oncogenic or pro-oncogenic depending on context. Although we did not directly examine the extent to which SMAD3 mislocalization contributes to the oncogenic effects of XPO4 loss, we observed that suppression of XPO4 stimulates TGF-β signaling, which can promote invasion and metastasis in late-stage liver cancer (Teufel et al., 2007). Similarly, EIF5A2 overexpression occurs in many tumor types (Clement et al., 2003; Clement et al., 2006). EIF5A was initially purified from rabbit reticulocytes as a translation initiation factor but may have other activities (Caraglia et al., 2001). We see that XPO4 loss enhances proliferation through EIF5A2, which is itself oncogenic in mice. Furthermore, XPO4 re-expression in XPO4-deficient tumor cells inhibits proliferation, suggesting these cells depend on XPO4 loss. Our results indicate that XPO4 is a negative regulator of EIF5A2 that acts, presumably in the nucleus, to inhibit cellular proliferation. Therefore, although a precise biochemical mechanism remains to be determined, the XPO4-EIF5A2 signaling circuit appears relevant in hepatocellular carcinoma and other tumor types.

Some of the genes we identify point towards new strategies for cancer therapy. For example, several new tumor suppressors (here, FGF6 and FSTL5) encode secreted proteins whose systemic administration might restore tumor suppressor function and serve as new biological anti-cancer therapies (see also Bric et al., submitted). Moreover, although it may not be possible to directly restore XPO4 function to tumors, its inactivation leads to hyperactivation of SMAD3/TGF-β signaling and in principle may sensitize cells to SMAD3 inhibitors, now in clinical trials (Lahn et al., 2005). Furthermore, our studies suggest that EIF5A2 inhibition should have anti-tumor effects in XPO-4 deficient tumors. Of note, EIF5A1 and EIF5A2 are the only eukaryotic proteins containing the polyamine derived amino acid hypusine [Nε-94-amino-2-hydroxybutyl)lysine], which is required for their activity (Park et al., 1994) and whose biogenesis can be inhibited by small molecule drugs that have anti-proliferative effects in vitro (Park et al., 1994). Since XPO4 loss is associated with poor survival in breast cancer patients (Table S5), agents that target this pathway may be clinically important.

The strategy outlined herein describes an approach to cancer gene discovery. Most current efforts to catalog cancer genes rely solely on genomic approaches. While powerful, genomic approaches can be expensive and yield candidates based on statistical criteria. Virtually all candidates must be functionally validated in various in vitro or in vivo models, which is slow and likewise expensive. By incorporating our screening approach, it is possible to rapidly filter genomic information for genes that impact cancer development in vivo, and thus focus follow up studies on those that might be most clinically useful. Although our study used a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma and focused only on focal deletions, this relatively high throughput approach could be expanded to other mouse models, or include shRNA pools targeting genes affected by larger deletions, promoter methylation, or point mutations. Moreover, by exploiting the emerging libraries of full length cDNAs it should be possible to perform parallel screens for oncogenes involved in genomic amplifications. We believe that such integrative approaches will provide a cost-effective strategy for functionally annotating the cancer genome.

Experimental procedures

Representational Oligonucleotide Microarray Analysis ”ROMA”

86 HCC tumors and 12 HCC cell lines from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN), Hannover Medical School and the University of Hong Kong have been analyzed by ROMA array-CGH method to generate genome-wide profiling of DNA copy number at high resolution (Lucito et al., 2003). Focal deletions are defined as segmented DNA copy number<=0.75 and size<=20 Mb. This analysis detected a total of 130 focally deleted loci, 44 of which were recurrent. The total number of genes within these loci was 3,503. In order to reduce the number of genes, we filtered the deletions by size (<=2.6 Mb) and derived a subset of 58 deleted loci containing 362 genes (Table S1). Methods for calculation of gene deletion frequencies are described in the supplemental information (see also Xue et al. 2008; Kraznitz et al. in preparation)

shRNA library cloning and vector construction

miR30 design shRNAs were subcloned from the pSM2 library vector into an MSCV-SV40-GFP recipient vector in pool sizes of 48. Maintenance of complexity of was verified by sequencing. The coding regions of human EIF5A1 and EIF5A2 were PCR cloned from pCMVsport6 (Open Biosystems) into MSCV-IRES-GFP with a 6xMyc-tag. Myc was expressed using MSCV-based retroviral vectors.

Generation of immortalized liver progenitor cell populations

Isolation, culture and retroviral infection of murine hepatoblasts were described recently (Zender et al., 2005; Zender et al., 2006). Liver progenitor cells from ED=18 p53−/− fetal livers were infected with MSCV based retroviruses expressing Myc–IRES-GFP or Myc-IRES-Luciferase and established cell populations were derived from two different preparations.

Generation of liver carcinomas

Early passage immortalized liver progenitor cells were transduced by retroviruses expressing single shRNAs or shRNA pools. 2×106 cells were transplanted into livers of female C57/B6 or NCR nu/nu mice (6–8 weeks of age) by intra-splenic injection or injected subcutaneously on NCR nu/nu mice. Tumor progression was monitored by abdominal palpation, whole body GFP imaging and bioluminescence imaging (IVIS system, Xenogen). Subcutaneous tumor volume was measured by caliper and calculated as 0.52 × length × width2. Bioluminescence imaging was as described (Xue et al., 2007).

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Histopathological evaluation of murine liver carcinomas was performed by an experienced pathologist (P.S.) using paraffin embedded liver tumor sections stained with Hematoxylin/Eosin (H&E). β-catenin antibody (BD biosciences, 1:100) staining was performed using standard protocols on paraffin embedded liver tumor sections.

Immunoblotting and nuclear fractionation

Fresh tumor tissue or cell pellets were lysed in Laemmli buffer using a tissue homogenizer. Equal amounts of protein (16ug) were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Nuclear fractionation was performed as described (Hosking et al., 2007). Antibodies are listed in the supplemental information.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes. Fixed cells were blocked with 5% goat serum and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 hour followed by goat-anti-mouse Alexa 568 or goat-anti-rabbit Alexa 488 secondary antibodies for 1 hour with washing in between. Microscopy was done using a confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Tissue culture, RNA analysis and retroviral gene transfer

Retroviral-mediated gene transfer was performed using Phoenix packaging cells (G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA) as described (Schmitt et al., 2002). Population doubling, BrdU staining, colony formation assays were as described. RNA expression analysis and PCR primers are described in the supplemental information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ken Nguyen, Stefanie Muller, Kristin Diggins-Lehet and Lisa Bianco and her team for excellent technical assistance, and Ravi Sachidanandam for assistance with computational analyses. We acknowledge members of the Lowe lab for constructive criticism and discussions throughout the course of this work. This work was supported by gifts from the Alan and Edith Seligson and the Don Monti Memorial Research Foundations, and grants from the German Research foundation (Emmy Noether Program), the Rebirth Excellence Cluster, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (C.P.S.) and grants CA13106, CA87497 and CA105388 from the National Institutes of Health. W.X. is in the MCB graduate program at Stony Brook University. G.J.H. and S.W.L. are Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigators.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Benne R, Hershey JW. The mechanism of action of protein synthesis initiation factors from rabbit reticulocytes. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3078–3087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraglia M, Marra M, Giuberti G, D'Alessandro AM, Budillon A, Del Prete S, Lentini A, Beninati S, Abbruzzese A. The role of eukaryotic initiation factor 5A in the control of cell proliferation and apoptosis. Amino Acids. 2001;20:91–104. doi: 10.1007/s007260170050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L, Gray JW. Translating insights from the cancer genome into clinical practice. Nature. 2008;452:553–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow LM, Baker SJ. PTEN function in normal and neoplastic growth. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement PM, Henderson CA, Jenkins ZA, Smit-McBride Z, Wolff EC, Hershey JW, Park MH, Johansson HE. Identification and characterization of eukaryotic initiation factor 5A-2. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:4254–4263. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement PM, Johansson HE, Wolff EC, Park MH. Differential expression of eIF5A-1 and eIF5A-2 in human cancer cells. FEBS J. 2006;273:1102–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickins RA, Hemann MT, Zilfou JT, Simpson DR, Ibarra I, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Probing tumor phenotypes using stable and regulated synthetic microRNA precursors. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1289–1295. doi: 10.1038/ng1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin SG, Ragland RL, Arlt MF, Mulle JG, Warren ST, Glover TW. Replication stress induces tumor-like microdeletions in FHIT/FRA3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:246–251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708097105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomase VS, Tagore S, Kale KV, Bhiwgade DA. Oncogenomics. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:199–206. doi: 10.2174/138920008783884713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan XY, Fung JM, Ma NF, Lau SH, Tai LS, Xie D, Zhang Y, Hu L, Wu QL, Fang Y, Sham JS. Oncogenic role of eIF-5A2 in the development of ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4197–4200. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan XY, Sham JS, Tang TC, Fang Y, Huo KK, Yang JM. Isolation of a novel candidate oncogene within a frequently amplified region at 3q26 in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3806–3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Takano H, Lapuk AV, Fridlyand J, Mao JH, Yu M, Miller MA, Santos JL, et al. Amplification of PVT1 contributes to the pathophysiology of ovarian and breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5745–5755. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann MT, Fridman JS, Zilfou JT, Hernando E, Paddison PJ, Cordon-Cardo C, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. An epi-allelic series of p53 hypomorphs created by stable RNAi produces distinct tumor phenotypes in vivo. Nat Genet. 2003;33:396–400. doi: 10.1038/ng1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks J, Krasnitz A, Lakshmi B, Navin NE, Riggs M, Leibu E, Esposito D, Alexander J, Troge J, Grubor V, et al. Novel patterns of genome rearrangement and their association with survival in breast cancer. Genome Res. 2006;16:1465–1479. doi: 10.1101/gr.5460106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie Y, Suzuki A, Kataoka E, Sasaki T, Hamada K, Sasaki J, Mizuno K, Hasegawa G, Kishimoto H, Iizuka M, Naito M, Enomoto K, Watanabe S, Mak TW, Nakano T. Hepatocyte-specific Pten deficiency results in steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1774–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking CR, Ulloa F, Hogan C, Ferber EC, Figueroa A, Gevaert K, Birchmeier W, Briscoe J, Fujita Y. The transcriptional repressor Glis2 is a novel binding partner for p120 catenin. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1918–1927. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau TR, Way JC, Silver PA. Nuclear transport and cancer: from mechanism to intervention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:106–117. doi: 10.1038/nrc1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall J, Liu Q, Bakleh A, Krasnitz A, Nguyen KC, Lakshmi B, Gerald WL, Powers S, Mu D. Oncogenic cooperation and coamplification of developmental transcription factor genes in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16663–16668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimpenfort P, Ijpenberg A, Song JY, van D, Nawijn V, Zevenhoven MJ, Berns A. p15Ink4b is a critical tumour suppressor in the absence of p16Ink4a. Nature. 2007;448:943–946. doi: 10.1038/nature06084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahn M, Kloeker S, Berry BS. TGF-beta inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:629–643. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS. Comparative and integrative functional genomics of HCC. Oncogene. 2006;25:3801–3809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucito R, Healy J, Alexander J, Reiner A, Esposito D, Chi M, Rodgers L, Brady A, Sebat J, Troge J, et al. Representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis: a high-resolution method to detect genome copy number variation. Genome Res. 2003;13:2291–2305. doi: 10.1101/gr.1349003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MH, Wolff EC, Lee YB, Folk JE. Antiproliferative effects of inhibitors of deoxyhypusine synthase. Inhibition of growth of Chinese hamster ovary cells by guanyl diamines. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27827–27832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahshor S, Woodgett JR. The links between axin and carcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:225–236. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.009506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Baranov E, Hoffman RM, Lowe SW. Dissecting p53 tumor suppressor functions in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segditsas S, Tomlinson I. Colorectal cancer and genetic alterations in the Wnt pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:7531–7537. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JM, Li MZ, Chang K, Ge W, Golding MC, Rickles RJ, Siolas D, Hu G, Paddison PJ, Schlabach MR, et al. Second-generation shRNA libraries covering the mouse and human genomes. Nat Genet. 2005 doi: 10.1038/ng1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel A, Staib F, Kanzler S, Weinmann A, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Galle PR. Genetics of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2271–2282. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga E, Oki E, Egashira A, Sadanaga N, Morita M, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y. Deregulation of the Akt pathway in human cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:27–36. doi: 10.2174/156800908783497140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke T, Jacks T. Cancer modeling in the modern era: progress and challenges. Cell. 2002;108:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lindern M, Fornerod M, Soekarman N, van Baal S, Jaegle M, Hagemeijer A, Bootsma D, Grosveld G. Translocation t(6;9) in acute non-lymphocytic leukaemia results in the formation of a DEK-CAN fusion gene. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1992;5:857–879. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(11)80049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Krasnitz A, Lucito R, Sordella R, Vanaelst L, Cordon-Cardo C, Singer S, Kuehnel F, Wigler M, Powers S, et al. DLC1 is a chromosome 8p tumor suppressor whose loss promotes hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1439–1444. doi: 10.1101/gad.1672608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta N, Fujii T, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Nishiguchi H, Endo Y, Toji S, Tanaka H, Nishimune Y, Nojima H. Structure, expression, and chromosome mapping of LATS2, a mammalian homologue of the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene lats/warts. Genomics. 2000;63:263–270. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, Silke J, Fan ST, Luk JM, Wigler M, Hannon GJ, et al. Identification and validation of oncogenes in liver cancer using an integrative oncogenomic approach. Cell. 2006;125:1253–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zender L, Xue W, Cordon-Cardo C, Hannon GJ, Lucito R, Powers S, Flemming P, Spector MS, Lowe SW. Generation and analysis of genetically defined liver carcinomas derived from bipotential liver progenitors. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:251–261. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.