Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas in variable organs. Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9 is important in the innate immune response against both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Propionibacterium acnes, candidate causative agents in sarcoidosis. The aim of our study was to investigate possible genetic and functional differences in TLR-9 between patients and controls. TLR-9 single nucleotide polymorphisms were genotyped in 533 patients and divided into a study cohort and validation cohort and 185 healthy controls. Furthermore, part of the promotor as well as the entire coding region of the TLR-9 gene were sequenced in 20 patients in order to detect new mutations. No genetic differences were found between patients and controls. In order to test TLR-9 function, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 12 healthy controls and 12 sarcoidosis patients were stimulated with a TLR-9 agonist and the induction of interleukin (IL)-6, interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-23 was measured. Sarcoidosis patients produce significantly less IFN-γ upon stimulation with different stimuli. Regarding IL-23 production, a significant difference between patients and controls was found only after stimulation with the TLR-9 agonist. In conclusion, we did not find genetic differences in the TLR-9 gene between sarcoidosis patients and controls. Sarcoidosis patients produce less IFN-γ regardless of the stimulating agent, probably reflecting the anergic state often seen in their peripheral blood T lymphocytes. The differences in TLR-9-induced IL-23 production could indicate that functional defects in the TLR-9 pathway of sarcoidosis patients play a role in disease susceptibility or evolution.

Keywords: cytokine production, polymorphisms, sarcoidosis, Toll-like receptor-9

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder of unknown aetiology leading to the formation of non-caseating granulomas in variable organs such as lungs, lymph nodes and skin. The disease is characterized by a strong cell-mediated immune reaction, making microbial pathogens such as viruses or intracellular bacteria leading candidates as causative agents. In particular, the intracellular bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Propionibacterium acnes have been studied extensively and may well play a role in disease pathogenesis [1–5].

In recent years, many genetic association studies have been performed with an emphasis on innate immunity [6–12]. An important category of innate immunity receptors are the Toll-like receptors (TLR), a family of related transmembrane or endosomal molecules each recognizing a distinct, but limited, repertoire of microbial encoded molecules. Two of the TLR genes, TLR-4 and TLR-9, are located in the close vicinity of chromosomal positions that have shown linkage in a previous study on predisposing gene loci in sarcoidosis [13]. TLR-4 is an essential receptor for the recognition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), unique to the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. Further studies on a genetic role of TLR-4 in sarcoidosis provide conflicting results. In a recent study, all 10 known TLR genes on seven different chromosomal loci were tested for linkage with sarcoidosis [8]. Once again, a significant linkage between a locus on chromosome 9 (near TLR-4) and sarcoidosis was found. These results could partly explain the association found by Pabst and colleagues between a functional TLR-4 polymorphism and a chronic course of sarcoidosis [7]. However, in subsequent case–control analysis, no association was found with this functional TLR-4 polymorphism Asp299Gly and sarcoidosis, a result in concordance with other studies showing no genetic association [6,10].

The endosomal localized receptor TLR-9, capable of recognizing unmethylated nucleic acid motifs, is one of the most important receptors in the initiation of protective immunity against intracellular pathogens and necessary for an adequate immune response against both M. tuberculosis and P. acnes[14,15]. TLR-9 is expressed primarily in B cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and monocytes/macrophages [16]. Regarding the genetic role of TLR-9 in sarcoidosis, both linkage studies also reach conflicting results. In the most recent study by Schurmann and colleagues [8], a subanalysis regarding sib-pair families (families with two or more siblings with sarcoidosis) showed significant transmission distortion for a marker located near the TLR-9 gene on chromosome 3p. A significant linkage of a TLR-9 locus with sarcoidosis, however, was not found. In our opinion, the above results do not rule out a genetic role for TLR-9 in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis and warrants further study.

Taken together, when considering a causative role for intracellular pathogens in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis, the innate immunity receptor TLR-9, based on its involvement in the immune response against intracellular pathogens and its genomic location, seems an attractive candidate for genetic and functional analysis in sarcoidosis research. We hypothesize that alterations in TLR-9 function are involved in the aberrant immune response characterizing sarcoidosis and therefore are more prevalent in sarcoidosis patients. To address this hypothesis, we performed both a genetic and functional analysis of TLR-9 in sarcoidosis patients and healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Study subjects for genetic analysis

A total of 150 unrelated and randomly selected Dutch Caucasian patients presenting with sarcoidosis at the St Antonius Hospital (84 men and 66 women) were included in the study cohort. In 102 patients, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established when clinical findings were supported by histological evidence, and after the exclusion of other known causes of granulomatosis. Forty-eight patients presented with the classical Löfgren's syndrome of fever, erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and joint symptoms. Verbal and written consent was obtained from all subjects, and authorization was given by the Ethics Committee of the St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein. The control subjects comprised 185 healthy Dutch Caucasian employees of the St Antonius Hospital in the Netherlands. By completing a questionnaire, relevant background information was provided by these volunteers and included medication, ethnicity and hereditary diseases. As a validation cohort, 383 unrelated and randomly selected Caucasian patients with sarcoidosis (190 men and 193 women, 323 patients with non-Löfgren sarcoidosis and 60 patients with Löfgren's syndrome). All patients were diagnosed as described above and written consent was obtained from these subjects as well as approval by the Ethics Committee of the St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein.

Evaluation of pulmonary disease severity

Pulmonary disease severity of sarcoidosis patients at presentation was evaluated by chest radiography and pulmonary function testing. Longitudinal chest radiographs for each patient were examined and compared to determine disease outcome. Chest radiographs at presentation, 2 years and 4 years were collected for each patient and assessed blind by a pulmonary physician for disease severity using standard radiographic staging for sarcoidosis. In brief, this comprises five stages: stage 0: normal; stage I: bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL); stage II: BHL and parenchymal infiltration; stage III: parenchymal infiltration without BHL; and stage IV: irreversible fibrosis with loss of lung volume. Radiographic evolution over a minimum 4-year period was available for 313 patients and was categorized as follows: A (normalization of improvement towards stage I), B (persistent stages II/III or progression in that direction and C (stable stage IV or progression towards this stage) [17]. Patients who have been diagnosed with Löfgren's syndrome at presentation were considered as a distinct group, with radiographic evolution not exceeding stage I.

Analysis of genetic polymorphisms in the TLR-9 gene

Genomic DNA extracted from all subjects in the study cohort and controls was genotyped for four different TLR-9 single nucleotide polymorphisms using sequence-specific primers (SSPs) and polymerase chain reaction or Taqman genotyping assay when appropriate (−1486). Selection of the polymorphisms was based on a minor allele frequency of more than 10% [18] and functionality [19]. The polymorphisms were located at the following nucleotide positions: −1486 (rs187084, promotor region), −1237 (rs5743839, promotor region), +1173 (rs352139, intron1/exon2) and +2848 (rs352140, exon2). Identification of the polymorphism at location –1486 was performed using the dual-labelled allele-specific oligonucleotides 5′-[FAM]-AATGACACGGACCCGT-[NFQ] and 5′-[VIC™]-TCAGCTTCTTAAGGGCA-[NFQ], together with forward primer 5′-CGTCTTATTCCCCTGCTGGAA and reverse primer 5′-TGGGCACTGTACTGGATCCT, following the manufacturer's instructions (Custom TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assay; Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For identification of the polymorphism at position −1237 the sequence-specific forward primers 5′-CATATGAGACTTGGGGGAGTTTT and 5′-ATATGAGACTTGGGGGAGTTTC were combined with the reverse primer 5′-ACTAGGTCCCTCCTCTGCT, leading to an expected polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product size of 231 base pairs (bp). For identification of the polymorphism at position +1173 the sequence-specific forward primers 5′-AAGTGGAGTGGGTGGAGGTA and 5′-AAGTGGAGTGGGTGGAGGTG were combined with the reverse primer 5′- ATGCGGTTGGAGGACAAGGA, leading to an expected PCR product size of 284 bp. For identification of the polymorphism at position +2848 the sequence-specific forward primers 5′-ACTCATTCACGGAGCTACCG and 5′-CACTCATTCACGGAGCTACCA were combined with the reverse primer 5′-TGGAAGAAGTGCAGATAGAGGT, leading to an expected PCR product size of 259 bp. In all primer mixes we included control primers 5′-ATGATGTTGACCTTTCCAGGG and 5′-GCAACTGATGAAAAGTTACAGAA, leading to an expected PCR product size of 720 bp. All PCR reactions were run under identical conditions, as described previously [20]. In the validation cohort, one of the two promotor polymorphisms was studied (−1486, rs187084), as well as the exon 2 polymorphism (+2848, rs352140). Analysis was performed using a custom Illumina goldengate bead single nucleotide polymorphism assay following the manufacturer's recommendations (San Diego, CA, USA).

Sequencing of the promoter and exons of TLR-9

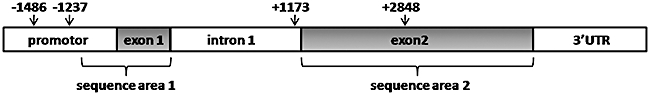

In 20 patients (including seven patients with Löfgren's syndrome) the last 300 bp of the promotor in combination with the entire coding region (2 exons) of TLR-9 was sequenced (Fig. 1). The following primers were used; 5′-TCTAGGGGCTGAATGTGACC with 5′-ACAACCCGTCACTGTTGCTT (promotor/exon 1), 5′-GGAGAGAGGGGTTGGAAGAT with 5′-GCATTCAGCCAGGAGAGAGA (exon 2), 5′-CTGCGTGTGCTCGATGTG with 5′-AGCCACGAAGCTGAAGTTGT (exon 2), 5′-GGTGCTAGACCTGTCCCACA with 5′-CACAGGTGGAAGCAGTACCA (exon 2) and 5′-TCAGCATCTTTGCACAGGAC with 5′-CCTCTGTCCCGTCTTTATGG (exon 2). The PCR mix consisted of 2·5 µl PCR buffer, 1·5 µl MgCl2 (25 mM), 0·5 µl of each 2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphate (dNTP) (1·25 mM), 0·25 µl HotStarTaq (all Applied Biosystems) and 16·25 µl demineralized water. Furthermore, 120 ng of DNA together with 5 pmol of each primer was added in order to obtain a reaction volume of 25 µl. Cycling parameters were 10 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 40 s at 94°C, 1 min at 59°C and 90 s at 72°C and finally 3 min at 72°C followed by 4 min at 4°C. The PCR products were purified using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands) following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, sequencing was performed using the BigDye® Terminator version 3·1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems), following the manufacturer's instructions on a ABI PRISM® 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The results were analysed with ABI PRISM® Seqscape® software version 2·0 (Applied Biosystems).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9 gene. The last 300 base pairs of the promoter together with exon 1 (sequence area 1) and exon 2 (sequence area 2) were sequenced. The relative positions of the four single nucleotide polymorphisms studied are marked by an arrow.

Analysis of TLR-9 function

Blood samples were collected from 12 randomly selected Dutch sarcoidosis patients visiting our out-patient clinic and 12 healthy Dutch employees from our hospital (all included in the cohort, see Study subjects for genetic analysis). Six patients used immunosuppressive therapy such as prednisolone or methotrexate. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from venous blood using Ficoll-Paque centrifugation and seeded on 24-well plates at a density of 400 000 cells per well. PBMCs were stimulated with the TLR-9 agonist ODN2216 (InvivoGen, Orlando, FL, USA) in combination with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, 42 µg; Murex, Dartford, UK). PHA alone (42 µg) and the control oligonucleotide for the TLR-9 ligand (ODN2216 control; InvivoGen) in combination with PHA (42 µg) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. PHA was used in addition to the TLR-9 agonist and TLR-9 control oligonucleotide due to the fact that stimulation with oligonucleotides only did not induce measurable amounts of cytokines. All stimulations were performed in a final volume of 1200 µl RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Breda, the Netherlands) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco) and 1% clindamycin/streptomycin. After a 24-h incubation period at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2, supernatant was collected. Interleukin (IL)-6 was chosen as a proinflammatory cytokine in order to rule out the possibility that sarcoidosis patients have a general unresponsiveness for stimuli. Measurement of interferon (IFN)-γ was chosen as a prototype T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine, IL-23 as a Th17 cytokine. IL-6, IFN-γ and IL-23 were determined by multiplex immunoassay as described previously [21,22]. To that end, Luminex beads were coated with appropriate catching antibodies (IL-6: clone MQ2-13A5, IL-23: clone eBio473P1, IFN-γ: clone NIB42 [Ready-Set-Go human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA] and matching biotin-conjugated antibodies were used for detection of bound cytokines (IL-6: clone MQ2-39C3, IL-23; clone C8·6, IFN-γ: clone 4S.B3 (Ready-Set-Go human ELISA kit; eBioscience).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Group comparisons of unpaired quantitative data were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. A P-value of < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Allelic distribution of TLR-9 polymorphisms

The genotype distribution of the investigated TLR-9 polymorphisms in Dutch sarcoidosis patients and controls are presented in Table 1. Genotype data from all populations conformed to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. No differences were found between patients and controls regarding the allelic distribution of any of the four polymorphisms. The two polymorphisms tested in a validation cohort, one promotor polymorphism and an exon 2 polymorphism, confirmed these data. Also, when comparing different clinical entities within the group of patients, no differences were found.

Table 1.

Genotype distribution of the Toll-like receptor polymorphisms in patients and controls.

| Study cohort |

Validation cohort |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Control n = 185 (%) | All patients n = 150 (%) | LOF n = 48 (%) | A n = 46 (%) | B n = 36 (%) | C n = 20 (%) | All patients n = 383 (%) | LOF n = 60 (%) | |

| −1486 | TT | 54(29·2) | 50(33·3) | 16(33·3) | 16(34·8) | 10(27·8) | 8(40·0) | 135(35·2) | 18(30·0) |

| TC | 100(54·1) | 72(48·0) | 25(52·1) | 21(45·7) | 20(55·6) | 6(30·0) | 186(48·6) | 35(58·3) | |

| CC | 31(16·8) | 28(18·7) | 7(14·6) | 9(19·6) | 6(16·7) | 6(30·0) | 62(16·2) | 7(11·7) | |

| −1237 | TT | 126(68·1) | 106(70·7) | 33(68·8) | 33(71·7) | 28(77·8) | 12(60·0) | ||

| TC | 55(29·7) | 42(28·0) | 15(31·3) | 12(26·1) | 8(22·2) | 7(35·0) | |||

| CC | 4(2·2) | 2(1·3) | – | 1(2·2) | – | 1(5·0) | |||

| +1173 | GG | 58(31·4) | 53(35·3) | 16(33·3) | 17(37·0) | 10(27·8) | 10(50·0) | ||

| GA | 97(52·4) | 69(46·0) | 22(45·8) | 20(43·5) | 20(55·6) | 7(35·0) | |||

| AA | 30(16·2) | 28(18·7) | 10(20·8) | 9(19·6) | 6(16·7) | 3(15·0) | |||

| +2848 | AA | 57(30·8) | 55(36·7) | 16(33·3) | 19(41·3) | 10(27·8) | 10(50·0) | 102(26·6) | 13(21·7) |

| AG | 97(52·4) | 69(46·0) | 23(47·9) | 19(41·3) | 20(55·6) | 7(35·0) | 190(49·6) | 36(60·0) | |

| GG | 31(16·8) | 26(17·3) | 9(18·8) | 8(17·4) | 6(16·7) | 3(15·0) | 91(23·8) | 11(18·3) | |

Radiographic evolution (over 4 years) category: LOF: Löfgren's syndrome; A: normalization or improvement towards stages 0/I; B: persistent stages II/III or progression towards stages II/III; C: stage IV at presentation or progression towards stage IV. Genotype frequencies are given in parentheses.

Sequence analysis of TLR-9

The sequence of the last 300 bp of the promotor region, together with the sequence of both exons 1 and 2 was determined in 20 patients in order to rule out the presence of new mutations in the gene encoding for TLR-9 (Fig. 1). In both patients with Löfgren's syndrome (n = 7) and patients with non-Löfgren sarcoidosis (n = 13), no mutations were found other than the known single nucleotide polymorphisms in the TLR-9 gene in this area.

Cellular stimulation of the TLR-9 pathway

In our genetic analysis we did not find differences between sarcoidosis patients and healthy controls. However, differences in transcription, translation or expression could still lead to functional differences. Therefore, in order to exclude the possibility of functional defects in the TLR-9 activation pathway in sarcoidosis patients, we tested the cytokine production upon stimulation with a TLR-9 agonist.

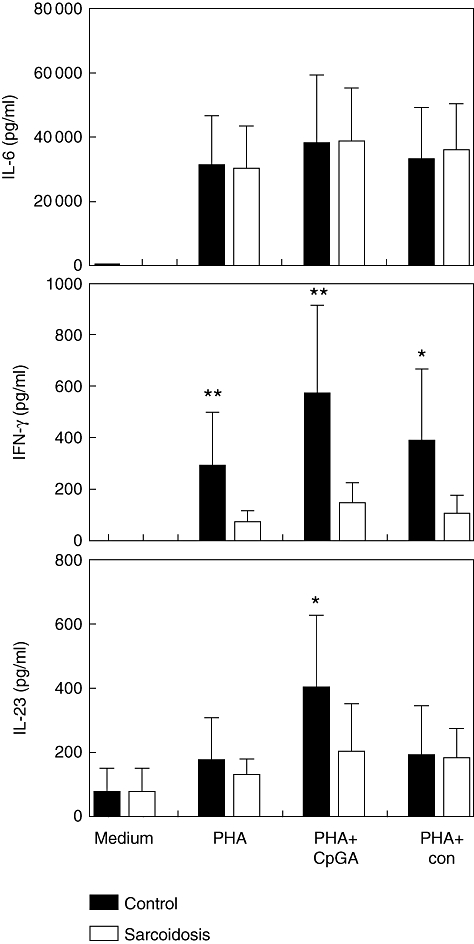

We found that sarcoidosis patients produce less IFN-γ upon stimulation with PHA, cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG)-A DNA and CpG-A control oligonucleotide (Fig. 2). As expected, IFN-γ production was slightly lower in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy in comparison with patients without these drugs (Fig. 3). When we measured TLR-9 induced IL-23 production a significant difference between patients and controls also was found (Fig. 2). In contrast to the IFN-γ data, there was no difference between patients and controls when stimulated with the CpG-A control nucleotide and only a small difference when stimulated with PHA. We did not find differences in IL-6 production upon stimulation between patients and controls indicative of a general ability in sarcoidosis patients to respond to stimuli.

Fig. 2.

Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9-induced interleukin (IL)-6, interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-23 production. Mean values are shown ± standard deviation. PHA, phytohaemagglutinin; CpG-A, cytosine-guanine dinucleotide, TLR-9 agonist; con, control nucleotide for CpG-A. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

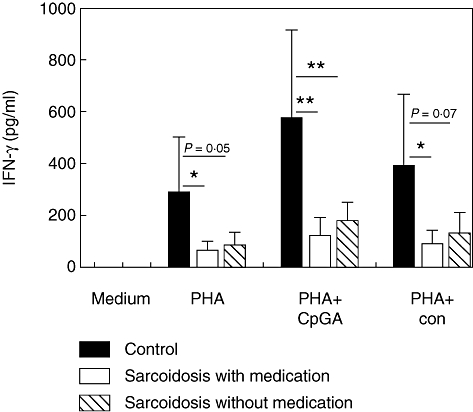

Fig. 3.

Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9-induced interferon (IFN)-γ production in healthy controls and sarcoidosis patients with or without immunosuppressive therapy. Mean values are shown ± standard deviation. PHA, phytohaemagglutinin; CpG-A, cytosine-guanine dinucleotide, TLR-9 agonist; con, control nucleotide for CpG-A. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

Discussion

In the present study we investigated the genetic and functional characteristics of the innate immunity receptor TLR-9 in Dutch sarcoidosis patients. Four well-known genetic polymorphisms in the TLR-9 gene were studied. We did not find an association between these polymorphisms and disease susceptibility or influence on disease course in Dutch sarcoidosis patients. The two polymorphisms tested in a validation cohort confirmed these data. Furthermore, to rule out genetic defects other than the known polymorphisms, the promotor region as well as exons 1 and 2 were sequenced in 20 patients. In patients with Löfgren's syndrome as well as patients with non-Löfgren sarcoidosis, no new mutations were found. Taken together, these results indicate that there is no difference in TLR-9 genetics between Dutch sarcoidosis patients and healthy controls, which is in line with the recent results of Schurmann et al. [8]. Conversely, however, it is more plausible that TLR-9 agonists such as M. tuberculosis and P. acnes are triggering agents in not all, but only a fraction of sarcoidosis patients. In this subgroup of patients a genetic role for TLR-9 could still exist. An elegant method to overcome this problem could be to subdivide patients by causative agents. In a recent study, it was estimated that 50% (n = 150) of sarcoidosis patients have T cell memory for antigens of M. tuberculosis[23]. In another study it was found that 35% (n = 50) of patients with sarcoidosis had an in-vitro response to a specific antigen of P. acnes, while none of the healthy controls responded [24]. In light of antigen recognition of M. tuberculosis and P. acnes in sarcoidosis patients using these T cell-based in-vitro assays, future studies in these potential subgroups of patients could reveal more insight into the role of TLR-9 polymorphisms in sarcoidosis.

In a situation where there is no genetic abnormality, functional abnormalities still could result from differences in transcription, translation or receptor expression. In order to explore fully the role of TLR-9 in sarcoidosis, it is therefore crucial to also obtain information about the function of this receptor in both patients and controls. We tested the cytokine production capacity upon stimulation with a TLR-9 agonist.

We found a decrease in IFN-γ production in sarcoidosis patients upon stimulation with a specific TLR-9 agonist. However, after stimulation with PHA, very often used as a positive control in in-vitro experiments, and the TLR-9 control nucleotide we also found a decrease in IFN-γ production. This could indicate several things. First of all, these data could reflect the anergic state of peripheral T cells often seen sarcoidosis patients [25–28]. This anergic state could be part of the immunological paradox stating that sarcoidosis is characterized by an excessive Th1 response, mainly at the pulmonary site, whereas circulating T cells respond poorly to antigen challenge. Secondly, decreased IFN-γ production could also be due to a numeral disequilibrium of specific T lymphocyte subsets. In previous experiments we have demonstrated a slightly lower amount of CD4+ T cells in sarcoidosis patients, indicating that this may be a contributing factor [29]. Thirdly, the genetic role of IFN-γ polymorphisms could also be of importance. We determined the allelic distribution of three different polymorphisms (Rs2069727, Rs2069718 and Rs1861493) in the IFN-γ gene in the 12 patients and 12 controls used for the in vitro experiments and found no differences (data not shown). The first two single nucleotide polymorphisms are the most important due to their linkage disequilibrium with the functional +874 A/T polymorphism [30,31], which influences the production capacity of IFN-γ by peripheral blood mononuclear cells and is associated with sarcoidosis [32,33]. Therefore, based on our results, genetic differences in the IFN-γ gene between patients and controls are not likely to explain the observed differences.

It is important to note that TLR-9 agonist-induced IFN-γ production was impaired in patients both with and without immunosuppressive therapy (Fig. 3). This suggests that possible abnormalities in the TLR-9 signalling pathway are an intrinsic characteristic of sarcoidosis and not the consequence of immunosuppression.

When we measured TLR-9-induced IL-23 production we also found a significant difference between patients and controls. However, in contrast to the IFN-γ data, there was no difference between patients and controls when stimulated with the TLR-9 control nucleotide. The differences between patients and controls after stimulation with PHA were modest, and not in the order of magnitude seen with IFN-γ. This could suggest that stimulation of TLR-9 is a potent inducer of IL-23, and it is even more interesting that this is somehow reduced in sarcoidosis patients, not based merely on T cell anergy. Further investigation of the role of IL-23 in sarcoidosis is of interest due to its important role in the Th17 pathway. It is known that P. acnes and M. tuberculosis induce both Th1 responses as well as Th17 responses [34,35]. It is therefore tempting to speculate that a dysregulated Th17 response due to insufficient IL-23 production upon stimulation with either P. acnes or M. tuberculosis plays a role in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis.

Regarding our IFN-γ and IL-23 data, it is important to state that the in-vitro experiments were performed using peripheral blood monocytes and lymphocytes, and not bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells. It is known that the TLR expression profile in human alveolar macrophages and monocytes is not identical [36]. As mentioned earlier, sarcoidosis is characterized by an immunological paradox. Therefore, it remains to be demonstrated if the differences we found between patients and controls will also be present in the pulmonary compartment. A next step in addressing the role of TLR-9 in sarcoidosis will be to repeat our experiments using BAL monocytes and lymphocytes and include a broader range of cytokines and chemokines.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that there are no genetic differences in the gene encoding for TLR-9 between Dutch patients and healthy controls. The results from our in vitro work demonstrate a decreased IFN-γ-producing capacity in sarcoidosis patients based probably on the anergic state of peripheral T cells. Importantly, we also found a TLR-9-specific decreased IL-23-producing capacity in sarcoidosis patients. Therefore, functional defects in the TLR-9 pathway of sarcoidosis patients could be of importance in disease susceptibility or evolution.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs H. Alpar-Kili, Mr J. Broess (Department of Clinical Chemistry, St Antonius Hospital) and Mrs D. Daniels-Hijdra (Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, St Antonius Hospital) for expert technical assistance. Drs H. van Velzen-Blad and A.M.E. Claessen are acknowledged for valuable advice during the design of this study.

Disclosure

All authors declare no conflict of interest. This study was supported by an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca®.

References

- 1.Dubaniewicz A, Kampfer S, Singh M. Serum anti-mycobacterial heat shock proteins antibodies in sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2006;86:60–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eishi Y, Suga M, Ishige I, et al. Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:198–204. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.198-204.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fite E, Fernandez-Figueras MT, Prats R, Vaquero M, Morera J. High prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in biopsies from sarcoidosis patients from Catalonia, Spain. Respiration. 2006;73:20–6. doi: 10.1159/000087688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazouli M, Ikonomopoulos J, Trigidou R, Foteinou M, Kittas C, Gorgoulis V. Assessment of mycobacterial, propionibacterial, and human herpesvirus 8 DNA in tissues of Greek patients with sarcoidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3060–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3060-3063.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Z, Marzilli L, Greenlee BM, et al. Mycobacterial catalase–peroxidase is a tissue antigen and target of the adaptive immune response in systemic sarcoidosis. J Exp Med. 2005;201:755–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazouli M, Koundourakis A, Ikonomopoulos J, et al. CARD15/NOD2, CD14, and toll-like receptor 4 gene polymorphisms in Greek patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pabst S, Baumgarten G, Stremmel A, et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 polymorphisms are associated with a chronic course of sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;143:420–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schurmann M, Kwiatkowski R, Albrecht M, et al. Study of Toll-like receptor gene loci in sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152:423–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanabe T, Ishige I, Suzuki Y, et al. Sarcoidosis and NOD1 variation with impaired recognition of intracellular Propionibacterium acnes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veltkamp M, Grutters JC, van Moorsel CH, Ruven HJ, van den Bosch JM. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 polymorphism Asp299Gly is not associated with disease course in Dutch sarcoidosis patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;145:215–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veltkamp M, Grutters JC, van Moorsel CH, et al. CD14 genetics in sarcoidosis patients; who's in control? Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2007;24:154–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veltkamp M, Wijnen PA, van Moorsel CH, et al. Linkage between Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 promotor and intron polymorphisms: functional effects and relevance to sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:453–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schurmann M, Reichel P, Muller-Myhsok B, Schlaak M, Muller-Quernheim J, Schwinger E. Results from a genome-wide search for predisposing genes in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:840–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2007056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalis C, Gumenscheimer M, Freudenberg N, et al. Requirement for TLR9 in the immunomodulatory activity of Propionibacterium acnes. J Immunol. 2005;174:4295–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bafica A, Scanga CA, Feng CG, Leifer C, Cheever A, Sher A. TLR9 regulates Th1 responses and cooperates with TLR2 in mediating optimal resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1715–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, et al. Quantitative expression of Toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grutters JC, Sato H, Pantelidis P, et al. Analysis of IL6 and IL1A gene polymorphisms in UK and Dutch patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20:20–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazarus R, Klimecki WT, Raby BA, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the Toll-like receptor 9 gene (TLR9): frequencies, pairwise linkage disequilibrium, and haplotypes in three U.S. ethnic groups and exploratory case–control disease association studies. Genomics. 2003;81:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novak N, Yu CF, Bussmann C, et al. Putative association of a TLR9 promoter polymorphism with atopic eczema. Allergy. 2007;62:766–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunce M, O'Neill CM, Barnardo MC, et al. Phototyping: comprehensive DNA typing for HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, DRB3, DRB4, DRB5 & DQB1 by PCR with 144 primer mixes utilizing sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) Tissue Antigens. 1995;46:355–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1995.tb03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de JW, Rijkers GT. Solid-phase and bead-based cytokine immunoassay: a comparison. Methods. 2006;38:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jager W, Prakken B, Rijkers GT. Cytokine multiplex immunoassay: methodology and (clinical) applications. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;514:119–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-527-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen ES, Wahlstrom J, Song Z, et al. T cell responses to mycobacterial catalase–peroxidase profile a pathogenic antigen in systemic sarcoidosis. J Immunol. 2008;181:8784–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebe Y, Ikushima S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Proliferative response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and levels of antibody to recombinant protein from Propionibacterium acnes DNA expression library in Japanese patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:256–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertran G, Arzt E, Resnik E, Mosca C, Nahmod V. Inhibition of interferon gamma production by peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes of patients with sarcoidosis. Pathogenic implications. Chest. 1992;101:996–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniele RP, Dauber JH, Rossman MD. Immunologic abnormalities in sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:406–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-3-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin JS, DeHoratius R, Israel H, Peake GT, Messner RP. Suppressor cell function in sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:169–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-2-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rottoli P, Muscettola M, Grasso G, Perari MG, Vagliasindi M. Impaired interferon-gamma production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells and effects of calcitriol in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1993;10:108–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heron M, Claessen AM, Grutters JC, van den Bosch JM. T cell activation profiles in different granulomatous interstitial lung diseases – a role for CD8(+)CD28(null) cells? Clin Exp Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04076.x. 17 December [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kantarci OH, Hebrink DD, Schaefer-Klein J, et al. Interferon gamma allelic variants: sex-biased multiple sclerosis susceptibility and gene expression. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:349–57. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim K, Cho SK, Sestak A, Namjou B, Kang C, Bae SC. Interferon-gamma gene polymorphisms associated with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1247–50. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.117572. Epub 16 November 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pravica V, Perrey C, Stevens A, Lee JH, Hutchinson IV. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the first intron of the human IFN-gamma gene: absolute correlation with a polymorphic CA microsatellite marker of high IFN-gamma production. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:863–6. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wysoczanska B, Bogunia-Kubik K, Suchnicki K, Mlynarczewska A, Lange A. Combined association between IFN-gamma 3,3 homozygosity and DRB1*03 in Lofgren's syndrome patients. Immunol Lett. 2004;91:127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miossec P, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:888–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zenaro E, Donini M, Dusi S. Induction of Th1/Th17 immune response by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of dectin-1, mannose receptor, and DC-SIGN. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1393–401. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0409242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juarez E, Nunez C, Sada E, Ellner JJ, Schwander SK, Torres M. Differential expression of Toll-like receptors on human alveolar macrophages and autologous peripheral monocytes. Respir Res. 2010;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]