Abstract

We have shown that immunization with dendritic cells (DCs) pulsed with hepatitis B virus core antigen virus-like particles (HBc-VLP) packaging with cytosine–guanine dinucleotide (CpG) (HBc-VLP/CpG) alone were able to delay melanoma growth but not able to eradicate the established tumour in mice. We tested whether, by modulating the vaccination approaches and injection times, the anti-tumour activity could be enhanced. We used a B16-HBc melanoma murine model not only to compare the efficacy of DC vaccine immunized via footpads, intravenously or via intratumoral injections in treating melanoma and priming tumour-specific immune responses, but also to observe how DC vaccination could improve the efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells to induce an enhanced anti-tumour immune response. Our results indicate that, although all vaccination approaches were able to protect mice from developing melanoma, only three intratumoral injections of DCs could induce a significant anti-tumour response. Furthermore, the combination of intratumoral DC vaccination and adoptive T cell transfer led to a more robust anti-tumour response than the use of each treatment individually by increasing CD8+ T cells or the ratio of CD8+ T cell/regulatory T cells in the tumour site. Moreover, the combination vaccination induced tumour-specific immune responses that led to tumour regression and protected surviving mice from tumour rechallenge, which is attributed to an increase in CD127-expressing and interferon-γ-producing CD8+ T cells. Taken together, these results indicate that repeated intratumoral DC vaccination not only induces expansion of antigen-specific T cells against tumour-associated antigens in tumour sites, but also leads to elimination of pre-established tumours, supporting this combined approach as a potent strategy for DC-based cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: adoptive T cell transfer, DC vaccine, intratumoral injections, ratio of CD8+ T cell/regulatory T cells, tumour mice model

Introduction

Because of the immunosuppressive or immunotolerance microenvironment within a tumour, inducing therapeutically useful anti-tumour immunity requires the development of powerful vaccination protocols [1–3]. Owing to the tolerogenic nature of cancer, approaches that lead to durable maintenance of functional T cells in tumour-bearing hosts are needed to maximize tumour regression. Because of their central role in controlling cell-mediated immunity, dendritic cells (DCs) hold much promise as cellular adjuvants in therapeutic cancer vaccines. Recently, rapid and remarkable progress in developing DC-based vaccines have been made and they have been reported to induce strong anti-tumour immune responses in animal experiments and in selected clinical trials involving cancer patients [4–7]. The ideal DC vaccines should be expected to generate large numbers of high-avidity effector CD8+ T cells and to overcome regulatory T cells and the suppressive environment established by tumours. However, clinical benefit measured by the regression of established tumours in patients has been observed in only a fraction of patients. This highlights the need to continually enhance the immunogenicity or immune strategy of DCs in order to enhance the anti-tumour efficacy of DC transfer-based immunotherapy.

The vaccination routes of DC vaccine include intratumoral injection, injection via footpads or into tail vein, and all administrations can result in regression of the tumour in vivo[8–10] or can boost the activity of adoptively transferred T cells in vivo[11]. However, whether the different administration approaches of DC-based vaccines have the same efficacy of inducing immunological and clinical responses in melanoma has not been determined.

Adoptive CD8+ T cell transfer has been shown to reduce established tumours significantly in both experimental models and cancer patients [12,13], and the anti-tumour activity of the adoptively transferred T cells could be boosted by transferred DCs [11,14]. However, from the published data it is not entirely clear whether the routes and frequencies of DC injection influence their ability to activate T cells.

We have previously described a mouse tumour model in which a single immunization of DCs pulsed with hepatitis B virus core antigen virus-like particles (HBc-VLP) packaged with cytosine–guanine dinucleotide (CpG) resulted in more significant inhibition of tumour growth than after immunization with DCs pulsed with HBc-VLP. Nevertheless, all the tumour-bearing mice died within 4 weeks and the failure of long-lasting protection to tumour growth needs to be determined [15].

To this end, in this study we not only investigated strategies to augment CD8+ T cell-mediated adoptive immunotherapy of tumour-bearing mice by DCs boosting vaccination, but we also observed that the correct route of DC administration could maximize tumour regression. Our results indicate that combined intratumoral injection of modified DC vaccines and adoptively transferred T cells could bring DC vaccines into full play and cause tumour regression.

Materials and methods

Mice and tumour cell line

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the animal centre of Hebei Medical University. The mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the central animal facility of Hebei Medical University. The B16 melanoma cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained according to the supplier's recommendations. B16-HBc cells, which can stably express HBc, were used as self-antigen expressing tumour cell.

Peptides

H2-kb-restricted HBc peptides (HBcAg93–100 MGLKFRQL) used for this study were synthesized and purified by high-power liquid chromatography (HPLC) to greater than 95% purity by Shanghai Bootech BioScience and Technology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). The peptide was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) before final dilution in endotoxin-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

DC generation and loading with HBc-VLP packaging with CpGs

Procedures for generating HBc-VLP/CpG-stimulated DCs have been described previously, with little modification [15]. Briefly, purified bone marrow-derived monocytes (BMDCs) were washed and resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (107/ml), and 30 µg HBc-VLP/CpG was incubated for 6 h in 1 ml of DMEM followed by maturation stimuli that were used at concentrations of 100 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli 0127:B8; Sigma Aldrich, WGK Germany) plus 5 µg/ml anti-CD40 (NA/LE; BD Pharmingen, USA).

Flow cytometric analysis

Activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were labelled with anti-interferon (IFN)-γ–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (clone; Pharmingen), anti-CD8-phycoerythrin (PE) (Pharmingen) and anti-CD127-FITC (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). For regulatory T cell (Treg) detection, anti-CD4-FITC (Pharmingen), and anti-CD25-PE (Pharmingen) or anti-forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)–PE (Pharmingen) were used. Stained cells were analysed on a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur) (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) flow cytometer and CellQuest software.

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assays

CD8+ CTL responses were assessed with a standard colorimetric assay (CytoTox 96, Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay; Promega, WI, USA), which measures the ability of in vitro-restimulated splenocytes to lyse target cells. Splenocytes pooled from immunized mice were restimulated in vitro in RPMI-1640 containing H2-kb/HBc peptide for 5–7 days. HBc+ target B16-HBc cells, which express HBc, were used as target cells. Different numbers of effector cells were incubated with a constant number of target cells (5 × 105/well) in 96-well U-bottomed plates (100 µl/well) for 4 h at 37°C. The supernatants were collected from triplicate cultures. The lysis percentage was calculated as (experimental release–spontaneous release)/(maximum release – spontaneous release) × 100.

Tumour growth and vaccination

Mice were inoculated with 0·2 million B16-HBc or B16 cells in 50 µl of PBS subcutaneously. Three days later, HBc-VLP/CpG-pulsed DCs (1 × 106/50 µl/mouse) were injected into the footpads or tail vein, or mice received the DCs by intratumoral injection. LPS was injected intraperitoneally directly following vaccination. Tumour growth was monitored by measuring the perpendicular diameter of the tumour, and survival was recorded daily.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunoperoxidase staining of FoxP3+ or CD8+ T cells was performed routinely on 5-µm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-imbedded tumours. Slides were incubated with the primary antibody (anti-FoxP3 or anti-CD8; eBioscience) overnight at 4°C. Immunodetection was performed using a secondary biotinylated-polyclonal anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) followed by an avidin–biotin complex staining kit (Vector) and 3′-3′ diaminobenzidine (liquid; Biogenex, San Ramon, CA, USA) for colour development. Samples were analysed with a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a 40 × objective.

Adoptive transfer therapy

To obtain tumour antigen-reactive T cells, 8–10-week-old C57BL mice were immunized twice (at 2-week intervals) with HBc-VLP packaging with CpG (100 µg/mouse, subcutaneous injection) and challenged subsequently with 2 × 105 live B16-HBc tumour cells (subcutaneous injection). Survivors were used as donors for tumour antigen-reactive T cells. One week prior to adoptive therapy, the donors were rechallenged with live B16-HBc tumour cells as above. On the day that adoptive therapy was conducted, the donors were killed and T cells were obtained from the spleen. The T cells were then restimulated with HBc peptide at a concentration of 20 µg/107 for 7 days.

For adoptive therapy, tumours were established by injecting 5 × 105 B16-HBc tumour cells subcutaneously on the right flank of C57BL mice (day 0). Palpable tumours (>5 mm in diameter) usually formed at the injection site after 5–6 days. On days 5 and 6, mice were each injected intratumorally with 5 × 106 activated HBc-specific CTL (50 µl), followed immediately by intravenous, intratumoral or via foodpad vaccination with 1 × 106 DCs pulsed with VLP packaging with CpG. One day later, LPS (30 µg/mouse) was administered intraperitoneally; two additional DC vaccinations were given at 6-day intervals. LPS was injected intraperitoneally directly following each vaccination. B16-HBc tumour growth was monitored by measuring the perpendicular diameters of tumours. Mice were killed when tumours exceeded 20 mm in diameter. Cured mice were each rechallenged (subcutaneously) with 5 × 105 B16-HBc tumour cells at least 7 weeks after the initial tumour inoculation. All the experiments were carried out in a blinded, randomized fashion and performed at least twice with similar results.

Quantitation of tumour-infiltrating T cells

B16-HBc tumours were established by injecting 0·5 × 106 tumour cells intradermally into the flank of C57/6J mice (day 0). From day 4 onwards, DCs transfers were performed as indicated above. On day 14 of the final DC inoculation, tumours were each excised, cut into small pieces and digested for 50 min at 37°C with 200 µg/ml type IV collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) [in RPMI-1640/10% fetal calf serum (FCS) medium]. Tissues were disrupted mechanically, and erythrocytes were depleted. Treg cells were quantitated by immunostaining with anti-CD4-FITC and anti-CD25-PE or anti-FoxP3-PE; CD8+ T cells with anti-CD8-PE. Cells were then analysed by flow cytometry. For each tumour sample, the numbers of various immune cells in 1 × 106 total tumour cells were each determined.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis we used Student's t-test, and a 95% confidence limit was taken to be significant, defined as P < 0·05. Results are presented typically as means ± standard errors (s.e.). Unless noted, data are presented as the mean ± s.e. of data from four to five mice.

Results

Tumour growth was delayed significantly by intratumoral vaccination with HBc-VLP-pulsed DCs

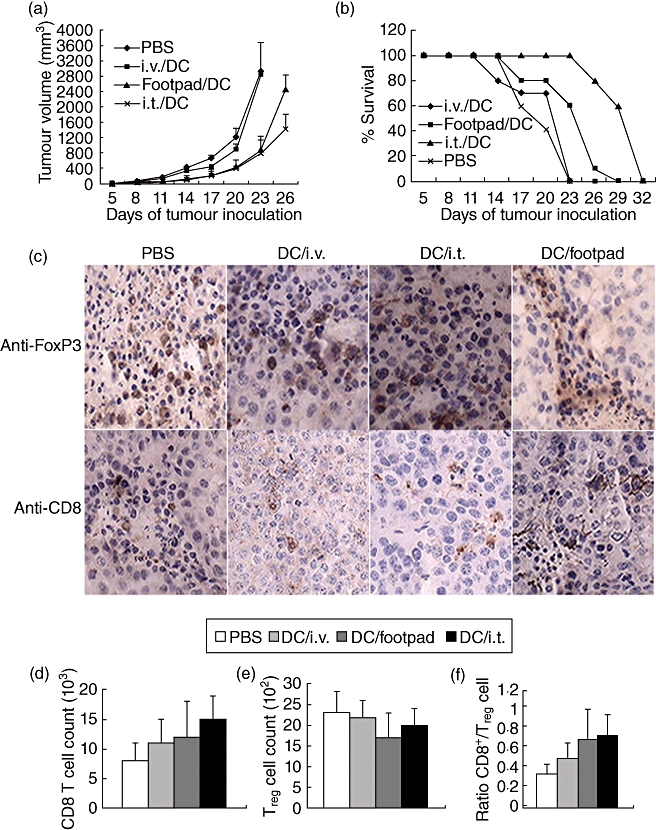

As a measure of the effectiveness of DC vaccine immunization alone, we evaluated the anti-tumour immunity generated after in vivo administration of DCs pulsed with HBc-VLP packaging with CpG. Five days after tumour inoculation, a single administration of DC vaccine via foodpad, intratumoral injection or into tail vein was conducted, respectively. The results have shown that, compared with untreated mice, DC vaccination in tail vein had no significant anti-tumour effect, whereas treatment with injection via foodpad or intratumoral injection resulted in a modest and temporary inhibition of tumour growth (Fig. 1a). The intratumoral vaccination regimen also resulted in prolongation of survival compared with the other treatment groups (Fig. 1b). However, all the mice eventually succumbed to the B16-HBc melanoma at the fourth week of tumour establishment.

Fig. 1.

Therapeutic dendritic cells (DCs) fail to reject the established tumours. (a) Tumour growth curve. Mice were inoculated with 0·2 million B16-HBc cells subcutaneously. Three days later, mice with tumours at least 3–4 mm in diameter were immunized (intratumorally, intravenously or via footpad) with 1·0 million hepatitis B virus core antigen virus-like particles (HBc-VLP) packaged with cytosine–guanine dinucleotide (CpG) (HBc-VLP/CpG) DCs. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was injected intraperitoneally directly following vaccination. Tumour growth and mouse survival were monitored. Tumour area was calculated by multiplying the width and length of the tumour. (b) Survival rate of mice were obtained by combining three independent experiments, each using 10 mice per group. Data are representative of three independent experiments (10 mice per group). (c) Tumours were harvested from mice in the different groups, and paraffin sections were stained with anti-forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) antibody in the top row. The bottom row shows tumour sections stained with anti-CD8. All images were acquired with a 40× objective. (d–f) In parallel experiments, tumours were harvested and analysed by flow cytometry for the expression of CD8, FoxP3 and the ratio of CD8+ T cells/regulatory T cells (Tregs). Tumours were pooled for each group, and data show the number of total FoxP3+ (d) or CD8+ cells (e) in the per 106 of cells, and the ratio of CD8+ cells to FoxP3+ cells infiltrating the tumours (f). (c–f) Data are representative of two independent experiments (three mice per group).

To observe lymphocyte infiltration and define clearly the lineage of infiltrated lymphocytes from the solid tumour of moribund mice, we assessed the CD8 and intracellular expression of FoxP3, the Treg lineage marker, on these cells by immunohistochemistry. Additionally, the numbers of CD8+ T cells or Treg cells were detected by flow cytometry. Figure 1c shows that some Treg cells were present within the tumours of mice receiving the DC vaccine, but no significant difference was observed from that of untreated mice. As expected, a single DC injection failed to induce CD8+ T cell accumulation and change the low ratio of CD8+ T cell/Treg cell (Fig. 1d–f).

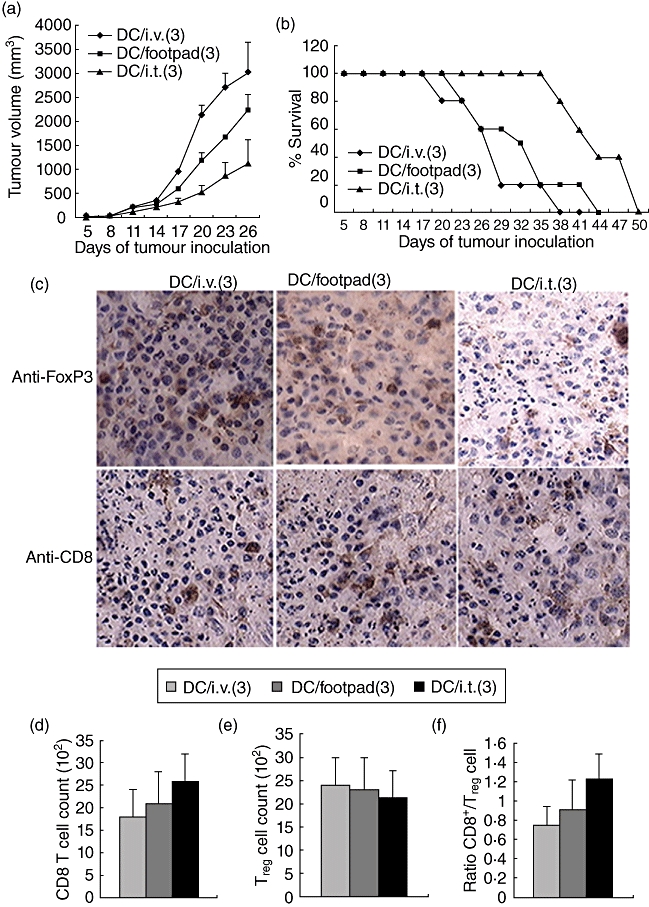

Multiple intratumoral vaccinations enhance the anti-tumour effect of DC vaccine

We next explored whether sequential DC vaccinations could enhance the anti-tumour effects. With an established tumour model, as depicted in Fig. 2a, three intratumoral vaccinations with DC pulsed with HBc-VLP/CpG resulted in a significant inhibition of tumour growth and prolonged mouse survival compared with foodpads or into tail vein. Importantly, only those mice receiving three intratumoral vaccinations survived for 5 weeks, but died by week 7 (Fig. 2b). These results suggest that although the multiple intratumoral DC vaccination regimen is more effective at inhibition of tumour growth than that of DC vaccinations via foodpad or tail vein, sequential DC vaccinations alone do not induce complete tumour regression.

Fig. 2.

Therapeutic dendritic cells (DCs) fail to reject the established tumours. (a) Tumour growth curve. Mice were inoculated with 0·2 million B16-hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBc) cells subcutaneously. Three days later, mice with tumours at least 3–4 mm in diameter were immunized (intratumorally, intravenously or via footpad) with 1·0 million hepatitis B virus core antigen virus-like particles (HBc-VLP) packaged with cytosine–guanine dinucleotide (CpG) (HBc-VLP/CpG) DCs, and two additional DC vaccinations were administered at 6-day intervals. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was injected intraperitoneally directly following each vaccination. DC/ intratumoral (3) means that DCs were injected intratumorally three sequential times. (b) Tumour growth and mouse survival were monitored. (a,b) Representative of three independent experiments (10 mice per group). (c) Tumours were harvested and analysed for the expression of anti-forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) and CD8 by immunohistochemistry. All images were acquired with a 40× objective; 14 days after tumour implantation, tumours were harvested and analysed for the expression of FoxP3 (d) and CD8 (e) by flow cytometry or CD8/FoxP3 (f). (c–f) Cumulative data from three different experiments (three mice per group).

To investigate further the impact of treatment on intratumoral immune responses, we quantified T cell infiltration and the ratio of effector T cell/Treg. Histological analysis of day 14 B16-HBc tumours from sequential DC-vaccinated mice revealed that, compared with a single DC vaccination, the numbers of FoxP3+ in all groups were not changed significantly, whereas the repeated antigen-specific DC vaccination resulted in a small increase of CD8+ T cell to infiltrate into tumours, especially in mice receiving intratumoral and footpad injections (Fig. 2c). Further quantity analysis showed that the numbers of CD8+ T cells and Tregs or their ratio had not changed significantly (Fig. 2d–f).

Enhanced anti-tumour activity was elicited by combination of DC vaccination and adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells

The results that multiple intratumoral vaccinations led to a significant delay in tumour growth and extension of mouse survival, but no cured mouse was observed, promoted us to explore a more effective regimen for DC-based tumour therapy.

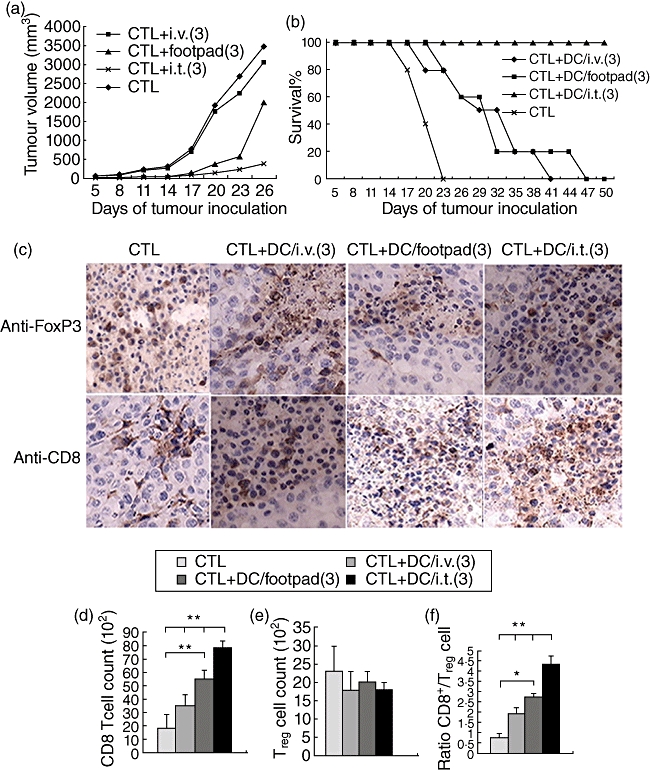

As expected, as negative controls, all untreated mice showed progressive tumour growth and died, whereas a proportion of mice treated with a combination of T cell transfer and either DC-vaccine injection intravenously or via footpad showed delayed tumour growth. On average, intravenous DC-vaccine treatment resulted in complete tumour regression in 15% of treated mice compared with 37% in DC-treatment via footpad (Table 1). In comparison, when mice were treated with adoptive T cell therapy and receiving three sequential intratumoral vaccinations, tumour growth was retarded significantly in a substantial portion of treated mice (Fig. 3a,b) and, on average, complete tumour regression was observed in 60% of treated mice (Table 1). In order to demonstrate the tumour antigen specificity of the therapy, we transferred DCs and T cells adoptively to the B16 tumour-bearing mice which did not express tumour antigen HBc. The results indicated that DCs failed to synergize with transferred T cells to inhibit tumour growth and all tumour-bearing mice died within 4 weeks (data not shown).

Table 1.

Different treatment of B16/hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBc) tumours.

| Fraction of mice cured per treatment groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiments | PBS | CD8 T | CD8 T + DCs/intravenous | CD8 T + DCs/footpad | CD8 T + DCs/intratumoral |

| 1 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 2/5 | 3/5 |

| 2 | 0/4 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 2/4 | 3/5 |

| 3 | 0/4 | 0/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 4/5 |

| 4 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 2/5 |

| Total | 0/18 | 0/20 | 3/20 | 7/19 | 12/20 |

| % | 0 | 0 | 15 | 37 | 60 |

Fig. 3.

Combined dendritic cell (DC) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) transfer therapy rejected the established tumours. (a) Tumour growth curve. Mice were inoculated with 0·2 million B16-hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBc) cells subcutaneously. Three days later, mice with tumours at least 3–4 mm in diameter were injected intratumorally with activated HBc-specific T cells, followed by intravenous, intratumoral or via foodpad vaccination with DCs pulsed with hepatitis B virus core antigen virus-like particles (HBc-VLP) packaged with cytosine–guanine dinucleotide (CpG) (HBc-VLP/CpG) three times at 6-day intervals. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was injected intraperitoneally directly following each vaccination. (b) Tumour growth and mouse survival were monitored. (a,b) Representative of three independent experiments (eight mice per group). (c–f) Recipient mice were killed 14 days after tumour challenge. Tumours were harvested and analysed for the expression anti-forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) and CD8 by immunohistochemistry (c); all images were acquired with a 40× objective. The data are presented as number of FoxP3+ cells (d), number of CD8+ T cells (e) and ratio of CD8+ T cells to FoxP3+ T cells (f). (c) Data are representative of two independent experiments (three mice per group); (e,f) representative of three independent experiments (four mice per group). Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation tumour samples from three independent experiments. The differences between different groups are statistically significant (**P < 0·01; *P < 0·05).

FoxP3-positive cells in tumour tissues did not show a decrease in the vaccinated groups, whereas an accumulation of CD8+ effector T cells was observed in mice vaccinated with DC, especially in the mice vaccinated intratumorally (Fig. 3c). DCs synergized with T cell transfer to further increase numbers of CD8+ T cells or the ratio of CD8+ T cell/Treg in tumour. These data reflect the impact upon the overall CD8+ T cell compartment, but do not address issues of specificity of the CD8+ T cells. To test these, we transferred DCs and T cells adoptively to the B16 tumour-bearing mice. Compared with the B16-HBc tumour-bearing mice, no CD8+ T cell accumulation was observed in tumour tissues (data not shown). Together, the results indicated that although the therapy did not result in elimination of Treg T cells, it promoted strong systemic T cell responses against B16-HBc melanoma, and small increases in CD8+ T cells in tumour tissue could contribute to tumour growth inhibition.

Combination of HBc/CpG-DC with adoptive antigen-specific T cell transfer induce long-lasting and systemic immunity in mice

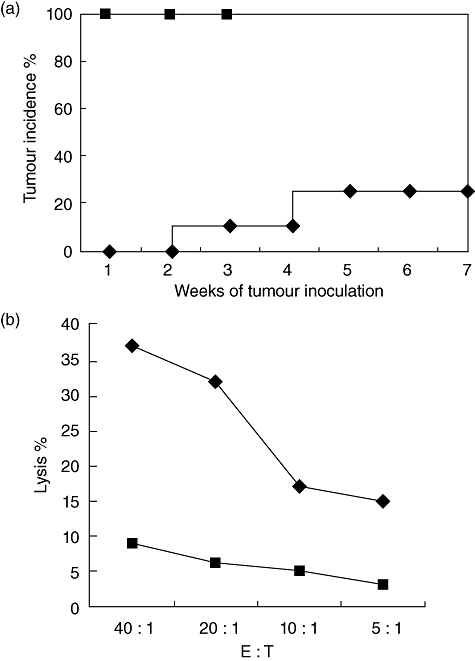

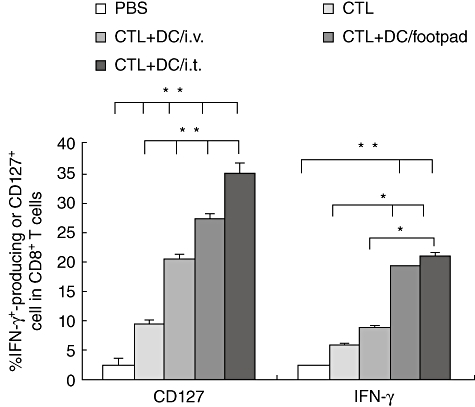

Our observation of local tumour regression, but not cure, in a substantial percentage of mice treated with both HBc/CpG-DC and adoptive T cell transfer prompted us to explore more long-term, systemic anti-tumour immunity in treated mice. To this end, cured mice in which the tumour volume was less than 300 mm3 and the survival period exceeded 7 weeks were rechallenged with B16-HBc tumour cells injected at sites posterior to the flank distant from the original tumour. Seventy-five per cent of these cured mice were resistant to rechallenge, whereas naive mice inoculated with the same tumour cells all died of tumours (Fig. 4a). Splenocytes from these cured mice, 3 weeks after tumour rechallenge, were observed to hold higher lysis activity to target tumour cells (Fig. 4b). In addition, the CD8+ T cells from rechallenged mice showed high levels of CD127 and IFN-γ expression, whereas the CD8+ T cells from naive mice expressed low levels of CD127 and IFN-γ (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Mice cured by combination of intratumoral injection of antigen-specific T cells and repeated intratumoral boost with dendritic cells (DCs). (a) A lethal dose 5 × 105 of the B16-hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBc) tumour cells was inoculated (subcutaneously) into naive mice ( ) or mice cured by combination of intratumoral transfer of T cells and DCs (♦) 8 weeks after initial tumour inoculation. Mice were monitored weekly for the appearance of tumours. All naive tumour-bearing mice died between weeks 3 and 4. (b) Bulk splenocytes were prepared 3 weeks after the rechallenge experiment described in (a) and restimulated in vitro with HBc peptide. Subsequently, splenocytes (effector) were incubated for 4 h with the B16-HBc tumour cells at indicated effector : target ratios, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity was determined by a standard colorimetric assay (♦). As negative control (

) or mice cured by combination of intratumoral transfer of T cells and DCs (♦) 8 weeks after initial tumour inoculation. Mice were monitored weekly for the appearance of tumours. All naive tumour-bearing mice died between weeks 3 and 4. (b) Bulk splenocytes were prepared 3 weeks after the rechallenge experiment described in (a) and restimulated in vitro with HBc peptide. Subsequently, splenocytes (effector) were incubated for 4 h with the B16-HBc tumour cells at indicated effector : target ratios, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity was determined by a standard colorimetric assay (♦). As negative control ( ), splenocytes from naive mice were assayed for CTL activity against the B16-HBc tumour cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments (three per group).

), splenocytes from naive mice were assayed for CTL activity against the B16-HBc tumour cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments (three per group).

Fig. 5.

Induction of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells response after vaccination with combination of intratumoral transfer of T cells and dendritic cells (DCs). Mice were vaccinated with intratumoral transfer of T cells or combination of T cells with DCs; phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated mice served as control. The splenic cells from immunized mice were stimulated with hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBc) peptide (HBcAg93–100 MGLKFRQL), then interferon (IFN)-γ-producing or CD127-expressing CD8+ T cells were detected. One representative experiment of three independent experiments is shown. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation of tumour samples from three independent experiments. The differences between different groups are statistically significant (**P < 0·01; *P < 0·05; three per group).

Together, these results showed a persistent, systemic anti-tumour immunity that was established in mice cured by therapy combining intratumoral DC vaccine transfer and adoptive T cell transfer.

Discussion

DC vaccines have been viewed as one of the most promising strategies for tumour vaccination [16–19]. In most cases, the administration approach of DC vaccines is subcutaneous injection (including injection into footpads) or intradermally, while DCs given intravenously result in responses in the spleen and are often ineffective for inhibiting tumour growth [20]. However, whether the route or timing of administration has a significant impact on CD8+ T cell/Treg infiltration and the resulting immune response had been unclear.

In this paper we first describe the effects of the DC injection route and timing on their ability to induce anti-tumour immune responses. We report that the single DC injection by intratumoral or via footpad was superior to the intravenous route: DC injected intratumorally or via footpad could induce better anti-tumour immune responses against the B16-HBc tumour compared to intravenously injected DC (Fig. 1a,b). Therefore, the injection route was important in determining the resulting anti-tumour response. However, none of the injection routes protected tumour-bearing mice (all tumour-bearing mice died within 4 weeks). The data indicate that the effective systemic anti-tumour immune responses was too strong to control the established tumour growth. This may be due to not more numbers of CD8+ T cells could accumulate to the tumour, or a lower ratio of CD8+ T/Treg (Fig. 1c). The immunosuppressive nature of cancer may also contribute to the depressed result. In our tumour model, nodules of 3–5 mm in size are already associated with a significant accumulation of Treg cells in the tumour infiltrate, which is indicative of an active tumour immune escape. Figure 1c shows that a single DC vaccine injection could not modulate the immunosuppressive state. Our previous experiments have also shown that, compared to PBS, intratumoral injection of CpG (10 µg/mouse) alone could induce an antigen-specific immune response in mice, as measured by both intracellular production of IFN-γ and in vivo killing assays by antigen-specific T cells. However, CpG injection could not elicit tumour growth inhibition [21].

In this study we have shown that repeated intratumoral DC injection led to delayed B16 tumour growth and prolonged mouse survival, but all tumour-bearing mice died within 7 weeks (Fig. 2a,b). The results may be due to the fact that repeated DC injection could not increase the homeostatic proliferation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and/or the ratio of CD8+ T cells with host-derived regulatory immune cells in tumours (Fig. 2c–e).

Although multiple intratumoral vaccinations with HBc/VLP-pulsed DCs have shown some promise in terms of inducing anti-tumour responses, immunization with DC vaccine alone rarely has the ability to lead to objective regression of large, established tumours. Some previous investigators have also found that adoptive transfer of high-avidity tumour-specific CTL populations failed to kill tumour cells due to the fact that CTL effector function is lost following tumour infiltration [22], while combined modified DCs and adoptively transferred T cells can induce an enhanced and considerably long anti-tumour response [11,13,14]. However, whether the injection method and frequency of DC vaccination could influence the anti-tumour activity of adoptively transferred T cells in vivo remains to be determined further.

In contrast to DC or CTL transfer therapy alone, the combination of antigen-pulsed DC vaccination and CTL therapy led to a more robust anti-tumour response, resulting in the substantial regression of large HBc-expressing B16 tumours and prolonged survival of tumour-bearing mice (Fig. 3a,b).

Tumour-infiltrating Treg cells play a major role in establishing and maintaining the state of immune suppression within the tumour microenvironment. Their inhibition could rescue the endogenous immune response from paralysis, thus leading to the rejection of tumours endowed with some immunogenicity [1]. However, CD25-directed Treg cell depletion, although efficiently preventing Treg cell accumulation, was insufficient to influence B16/BL6 tumour growth if administered in a ‘therapeutic’ setting. This failure appeared to correlate with a lack of trafficking of activated effector T cells into the tumour [23]. Efficient immunotherapy requires that cytotoxic T cells not only persist in vivo but also migrate to and function optimally at the tumour site. In this study, we have shown that large numbers of CD8+ T cells infiltrate B16-HBc tumours after antigen-specific T cell transfer following stimulation with antigen-pulsed DCs, suggesting that, compared with intravenous or footpad injection, repeated sequential intratumoral DC vaccinations can lead to improvement of the tumour immune microenvironment, and adoptively transferred T cells possess the capability of infiltrating tumours following antigen-specific stimulation in vivo (Fig. 3). Our results indicate that intratumoral vaccination with DCs have more potential than other vaccination approaches to improve the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment. Lou et al. has reported previously that administration of interleukin (IL)-2 intravenously with each DC vaccination led to synergistically augment the function of the adoptively transferred T cells and anti-tumour responses. Inclusion of vaccination without IL-2, however, failed to induce tumour regression [11]. Our results might be different, in that IL-2 could directly induce the adoptively transferred T cells to proliferate. In addition, perhaps all of great relevance to overcoming the dissociation of systemic and local responses, and up-regulation of IFN-γ, CD127 as well as CTL lysis activity rendered the tumour growth inhibition (Figs 4a,b and 5). Finally, it has been shown recently that T cell modulation combined with intratumoral CpG injection, which acts as a powerful stimulator of DCs, preferentially expands T-effector cells over Treg cells and cures large lymphoma tumours [24]. LPS injections boosted CTL responses significantly in mature DC mice, indicating the importance of not only the signalling of mature DCs for priming T cell responses [25], but also the long-term activity of DCs for a durable T cell response against tumours. Thus, our data suggest that all elements (antigen-specific T cell transfer, repeated booster vaccinations with DCs loaded with HBc-VLP packaging with CpGs and LPS injections following DC) are vital for efficacy in this preclinical model.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Key Program (no.06276102D-30, 08966104D) from Science and Technology Commission of Hebei province.

Disclosure

Nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Colombo MP, Piconese S. Regulatory-T-cell inhibition versus depletion: the right choice in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:880–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao YP, Schaue D, McBride WH. Modification of the tumor microenvironment to enhance immunity. Front Biosci. 2007;12:3576–600. doi: 10.2741/2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904–12. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang SH, Hong SY, Michele W, Qian JF, Yang J, Yi Q. Dendritic cell vaccine but not idiotype-KLH protein vaccine primes therapeutic tumor-specific immunity against multiple myeloma. Front Biosci. 2007;12:3566–75. doi: 10.2741/2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shigeo K, Sadamu H, Eiichi H, et al. In vitro generation of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells by fusions of human dendritic cells and hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Trans Med. 2008;6:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karimi K, Boudreau JE, Fraser K, et al. Enhanced antitumor immunity elicited by dendritic cell vaccines is a result of their ability to engage both CTL and IFN gamma-producing NK cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:411–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuler G, Schuler-Thurner B, Steinman RM. The use of dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:138–47. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu J, Yuan X, Belladonna ML, et al. Induction of potent antitumor immunity by intratumoral injection of interleukin 23-transduced dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8887–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersey P, Halliday GM, Farrelly ML, DeSilva C, Lett M, Menzies SW. Phase I/II study of treatment with matured dendritic cells with or without low dose IL-2 in patients with disseminated melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1039–51. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephanie PH, Shiau-Choot T, Kate AA, Yan J, Jacquie LH, Franca R. Activation and route of administration both determine the ability of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells to accumulate in secondary lymphoid organs and prime CD8+ T cells against tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0350-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lou Y, Wang G, Lizée G, et al. Dendritic cells strongly boost the antitumor activity of adoptively transferred T cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6783–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussman JJ, Shu S, Sondak VK, Chang AE. Activation of T lymphocytes for the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:296–06. doi: 10.1007/BF02303568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamai H, Watanabe S, Zheng R, et al. Effective treatment of spontaneous metastases derived from a poorly immunogenic murine mammary carcinoma by combined dendritic–tumor hybrid vaccination and adoptive transfer of sensitized T cells. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo H, Hazama S, Kawaoka T, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer using MUC1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and activated T lymphocytes. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:379–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song S, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Augmented induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell response and antitumor effect by DCs pulsed with virus-like particles loading with CpG. Cancer Lett. 2007;256:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharon C, Joseph H, Nurit H. Dendritic cell-based therapeutic vaccination against myeloma: vaccine formulation determines efficacy against light chain myeloma. J Immunol. 2009;182:1667–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilboa E. The promise of cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:401–11. doi: 10.1038/nrc1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilboa ED. C-based cancer vaccines. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1195–03. doi: 10.1172/JCI31205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralph MS. Dendritic cells in vivo: a key target for a new vaccine science. Immunity. 2008;29:319–24. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong L, Benike C, Wu L, Engleman EG. Dendritic cells injected via different routes induce immunity in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2001;166:4254–59. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Song S, Liu C, et al. Generation of chimeric HBc proteins with epitopes in E. coli: formation of virus-like particles and a potent inducer of antigen-specific cytotoxic immune response and anti-tumor effect in vivo. Cell Immunol. 2007;247:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janicki CN, Jenkinson SR, Williams NA, Morgan DJ. Loss of CTL functions among high-avidity tumor-specific CD8+ T cells following tumor infiltration. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2993–00. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi T, Hirota K, Nagahama K, et al. Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity. 2007;27:145–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brody JD, Goldstein MJ, Czerwinski DK, Levy R. Immunotransplantation preferentially expands T-effector cells over T-regulatory cells and cures large lymphoma tumors. Blood. 2009;113:85–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou B, Reizis B, DeFranco AL. Toll-like receptors activate innate and adaptive immunity by using dendritic cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic mechanisms. Immunity. 2008;29:272–82. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]