Abstract

Background

Methodological difficulties associated with QT measurements prompt search for new ECG markers of repolarization heterogeneity.

Objective

We hypothesized that beat-to-beat 3-dimensional vectorcardiogram variability predicts ventricular arrhythmia (VA) in patients with structural heart disease left ventricular systolic dysfunction and implanted ICD.

Methods

Baseline orthogonal ECGs were recorded in 414 patients with structural heart disease [mean age 59.4±12.0; 280 whites (68%) and 134 blacks (32%)] at rest before implantation of ICD for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. R and T peaks of 30 consecutive sinus beats were plotted in 3-D to form an R peaks cloud and a T peaks cloud. The volume of the peaks cloud was calculated as the volume within the convex hull. Patients were followed at least 6 months; sustained VA with appropriate ICD therapies served as an endpoint.

Results

During a mean follow-up time of 18.4±12.5 months, 61 of the 414 patients (14.73% or 9.6% per person-year of follow-up) experienced sustained VA with appropriate ICD therapies: 41 of them were whites and 20 were blacks. In the multivariate Cox model that included inducibility of VA and use of beta-blockers, the highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volume ratio significantly predicted VA (HR 1.68 95% CI 1.01–2.80;p=0.046) in all patients. T peaks cloud volume and T/R peaks cloud volume ratio were significantly smaller in blacks [0.09 (0.04–0.15) vs. 0.11 (0.06–0.22), p=0.002].

Conclusion

Relatively large T peaks cloud volume is associated with increased risk of VA in patients with structural heart disease and systolic dysfunction.

Keywords: Ventricular arrhythmia, risk stratification, vectorcardiogram, variability, repolarization

Introduction

In large randomized clinical trials, ICDs have been proved to provide survival benefit1–3 for HF patients with systolic dysfunction. White men compose the majority (70–85%) of study populations in clinical trials4, 5. Get with the Guidelines Program and Medicare & Medicaid data show that the ICD therapy is underutilized in blacks5. On the other hand, some studies have suggested that blacks might not benefit from ICD to the same extent as whites6, 7, but the data are inconclusive8. Race-specific guidelines for risk stratification of VA are needed; however, race-specific differences are not well described.

Increased temporal repolarization lability is recognized as a marker of susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia (VA). Different approaches to the assessment of temporal lability of repolarization have been proposed and used. Although metrics of spatial dispersion of repolarization vary in terms of the studied repolarization parameter [T-wave width 9, the total cosine R-to-T descriptor and total morphology dispersion10, T-wave shape indices11, T peak–T end interval12], methods of assessment of temporal heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization have been largely confined to the assessment of temporal QT variability, although methodological difficulties associated with QT measurements were previously shown.

Increased QT variability measured on surface ECG13, as well as increased intracardiac repolarization lability14, is associated with higher risk of sustained VA. Previously gender differences in repolarization lability were shown in the MADIT-II study population15, but racial differences were not explored. We hypothesized that measured in three dimensions beat-to-beat vectorcardiogram variability predicts VA in patients with structural heart disease, systolic dysfunction, and implanted ICD, and it may be helpful in studying racial differences.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University IRB, and all patients gave written informed consent before entering the study.

Study population

This report presents a data analysis of the first consecutive 414 participants in the PROSE-ICD study with at least 6 months of follow-up, recruited at the Johns Hopkins Hospital site. PROSE-ICD (NCT00733590) is an ongoing prospective observational multicenter cohort study of primary prevention ICD patients with structural heart disease. Patients with ischemic (myocardial infarction at least 4 weeks old) or nonischemic cardiomyopathy (at least 9 months), an ejection fraction less than or equal to 35% and stable NYHA class II-III heart failure symptoms on optimal heart failure medications were enrolled. NYHA Class I patients were included if they fulfilled MADIT II criteria: ischemic cardiomyopathy with LV EF less than or equal to 30%. Patients were excluded if the ICD was indicated for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), if they had a permanent pacemaker or a Class I indication for pacing, or if they were pregnant.

Surface ECG recording and analysis

Baseline modified Frank orthogonal XYZ leads ECG was recorded before ICD implantation during 5 minutes at rest by PC ECG machine (Norav Medical Ltd, Thornhill, ON, Canada) with a 1000 Hz sampling frequency.

ECG was considered eligible for repolarization lability analysis if it was recorded at sinus rhythm and number of excluded beats (premature ventricular or atrial complexes and noisy beats) did not exceed 15% of the epoch. Temporal beat-to-beat QT variability during sinus rhythm was measured automatically as previously described 16. The heart rate mean (HRm) and variance (HRv) and the QT interval mean (QTm) and variance (QTv) were computed from the respective time epochs (3–5 min). A normalized QT variability index (QTVI) was derived according to the equation: QTVI=log10[(QTv/QTm2)/(HRv/HRm2)]. All three orthogonal leads were analyzed separately, and then average QT variability values were calculated across XYZ leads. MTWA17, 18 was measured spectrally by custom-designed MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) software. MTWA test was considered positive if the absolute voltage of T wave alternation was more or equal 1.9 μV with MTWA exceeding noise at least 3 times (K score ≥3).

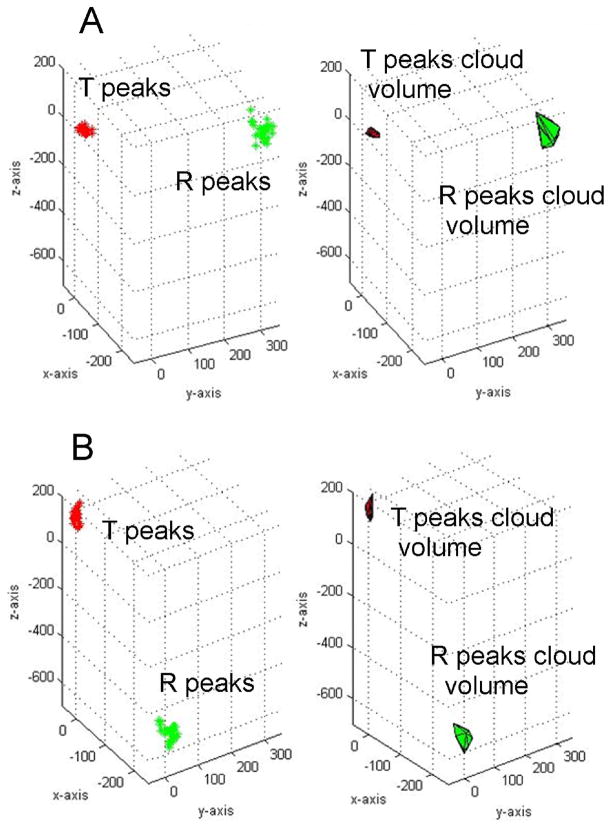

3D ECG variability analysis: the volume of R and T peaks cloud

Methodology of analysis was previously described19. Baseline wander was corrected with a zero- or first-order polynomial fit. In sinus rhythm ECG 30 consecutive sinus beats were selected, and premature ventricular complexes were manually excluded. The peaks of R-waves and T-waves were detected automatically in 3D ECG through use of custom-designed software written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). The peak of R-waves was found as the furthest point away from the origin of the three loops (Figure 1). The peak of T-waves was detected automatically as the furthest point away from the origin in a time frame following the detected R-wave peak. 3D ECG variability analysis was performed by an investigator blinded to the study outcomes (L.H.). Results were independently reviewed by two investigators (by L.H and L.G.T.) to ensure accuracy and quality of peaks detection. R and T peaks were plotted in 3D to form an R peaks cloud and a T peaks cloud. The peaks cloud points were used to form a convex hull, the convex shape with the smallest volume necessary to encompass all the wave peak points. The volume of the peaks cloud was calculated as the volume within the convex hull. The ratio of the T peaks cloud volume to the R peaks cloud volume was calculated. Cases of two distinct T peaks clouds were considered as positive 3D TWA (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Representative baseline T/R peaks cloud volumes in a patient without (A) and one with (B) subsequent sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia and appropriate ICD therapy at follow-up.

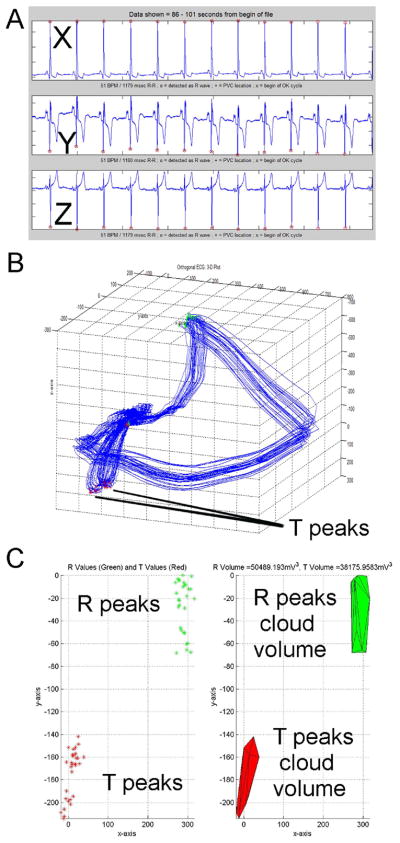

Figure 2.

Representative example of 3D ECG in patient with positive microvolt T wave alternans (Valt=33.4μV and K score = 12.0): (A) orthogonal XYZ ECG; (B) 3D ECG presented as QRS loop and visible 3D presentation of T wave alternans as “double T loop”; (C) “Double T peaks cloud” easily visible on 3D ECG.

Endpoints

Patients were followed prospectively with ICD device interrogation every 6 months. Appropriate ICD therapies [either shock or antitachycardia pacing] for VA served as the primary endpoint for analysis. ICD therapies were programmed at the discretion of the attending electrophysiologist. All stored ICD events data were reviewed by an independent endpoints adjudication committee, blinded to the results of the 3D ECG variability analysis. ICD therapies for monomorphic VT [defined as a tachycardia of ventricular origin with identical or nearly identical far field electrograms (EGM), associated with stable cycle length [CL] (beat-to-beat CL differences< 20 ms), polymorphic VT (tachycardia of ventricular origin with beat to beat variation in far-field EGM morphology, associated with unstable CL (beat-to-beat CL differences ≥ 20 ms) and average CL ≥200 ms], or ventricular fibrillation (sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia with unstable cycle length and EGM morphology and average CL <200 ms) were classified, as appropriate.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were computed using STATA 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables and as median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed variables. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was applied to skewed continuous variables—R peaks cloud volumes, T peaks cloud volumes, and T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio. Dichotomized variables were compared by Pearson’s chi-square test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient rs and interquartile regression coefficients were calculated to study relations between peaks cloud volumes metrics and routine orthogonal ECG repolarization lability parameters. We specified the high risk subgroups of patients by identifying separately those in the highest tertile of the T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio. Unadjusted and adjusted Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to compare the highest tertile of the T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio. The log-rank statistic was computed to test the equality of survival distributions. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed, and interaction with race was tested. Proportional hazards assumption was tested based on Schoenfield residuals for each Cox model.

Results

We analyzed data of 414 patients with baseline ECG eligible for repolarization lability assessment, among them there were 280 whites (68%) and 134 blacks (32%). Baseline patient clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Blacks were significantly younger than whites, had lower EF at baseline, and more often had non ischemic cardiomyopathy. However, there was no difference in the rate of revascularization procedures among ischemic cardiomyopathy patients. Similarly, there were nearly no differences in the use of medications, including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, and amiodarone. The one exception was beta-blockers, which were used by more blacks than whites. Nor were there racial differences in NYHA HF class and presence of BBB. VA was more frequently inducible by programmed stimulation during ICD implantation in whites.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Whites (n=280) | Blacks (n=134) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD, y | 61.1±11.3 | 55.8±12.7 | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic CM, n(%) | 179(63.9) | 48(35.8) | 0.0001 |

| Baseline LVEF ±SD, % | 22.7±8.8 | 20.5±8.0 | 0.012 |

| Complete BBB, n(%) | 21(7.5) | 6(4.5) | 0.244 |

| LVDD±SD, cm | 5.99±1.0 | 5.99±0.9 | 0.940 |

| Beta blockers, n(%) | 263(94) | 133(99) | 0.022 |

| PTCA and/or CABG history, n(%) | 126(76.4) | 34(75.6) | 0.910 |

| Amiodarone, n(%) | 78(28) | 28(21) | 0.390 |

| NYHA class III, n(%) | 138(49.5) | 69(51.5) | 0.541 |

| Inducible VT, n(%) | 88(39.1) | 18(19.2) | 0.001 |

During a mean follow-up time of 18.4±12.5 months, 61 of the 414 patients (14.73% or 9.6% per person-year of follow-up) experienced sustained VA with appropriate ICD therapies, among them 41 were white and 20 black. Polymorphic VT or ventricular fibrillation was diagnosed in 19 patients (4.6% or 3.1% per person-year of follow-up) and monomorphic VT in 42 patients (10.1 % or 6.7 % per person-year of follow-up). There were no significant differences in the rate of VA events in the gender, race, and type of cardiomyopathy subgroups.

Positive MTWA measured by spectral method at rest (HRm 72 ±14 bpm) were observed in 8 patients. Positive 3D TWA (Figure 2) was observed in 15 patients, including all 8 patients with positive MTWA. No one patient with positive MTWA or 3D TWA sustained VA during follow-up.

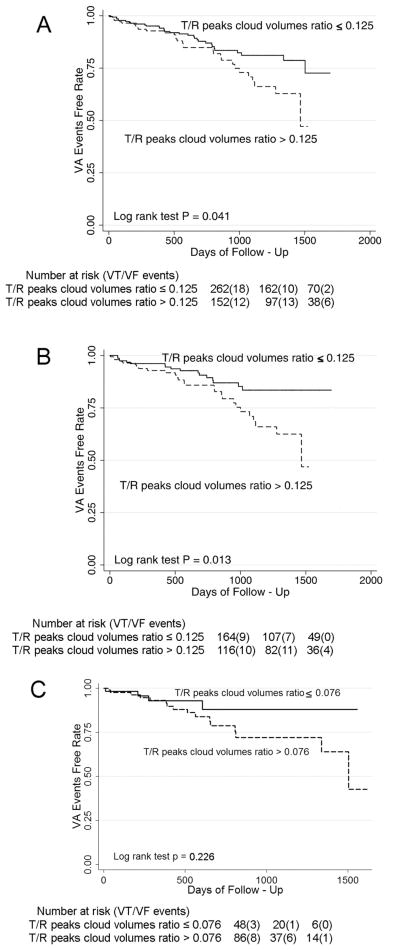

Predictive value of 3D repolarization lability measured as T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio

The highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio predicted VA during follow-up in all patients (Figure 3A). In whites the predictive value of the highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio was more prominent (Figure 3B), whereas it was not significant in blacks (Figure 3C). In a univariate Cox regression model, all patients with the highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio had a 1.5-times higher risk of VA during follow-up (HR 1.66 95% CI 1.02–2.72;p=0.043), whereas whites with the highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio had a 2-times higher risk of VA during follow-up (HR 2.12; 95% CI 1.15–3.89;p=0.015). As T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio was significantly lower in blacks than in whites, we selected different cutoff equal 0.076, separating the lowest and two higher tertiles of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio in blacks. However, T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio did not reach significance in prediction of VA events in blacks (HR 1.93, 95%CI 0.64–5.81, p=0.242).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for freedom from VA events in patients with the highest and two lower tertiles of the T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio: (A) all patients; (B) whites only; (C) blacks only with the lowest and two higher tertiles of the T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio.

In the multivariate Cox model that included inducibility of VA and use of beta-blockers, the highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio remained a significant predictor of VA (HR 1.68 95% CI 1.01–2.80;p=0.046) along with the use of beta-blockers (HR 0.43 95% CI 0.19–0.94;p=0.035) in all patients and in whites only (HR 2.16 95% CI 1.16–4.04;p=0.016). No significant interaction was found between race and T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio in the Cox regression model.

Combination of traditional QT variability with 3D ECG variability

Only 282 ECG recordings were eligible for beat-to-beat QT variability analysis after exclusion of ECGs with less than 85% analyzed beats during 3 min epoch. The highest quartile of QTVI (>−0.1) was determined as cut-off for Cox regression analysis. Combined repolarization lability index, defined as either QTVI>−0.1 or T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio >0.125 demonstrated improved predictive value (HR 2.63, 95% CI 1.37–5.02, p=0.003) for all patients, but was not significant for VA prediction in blacks only (HR 2.06, 95%CI 0.80–5.29, p=0.132).

Racial differences in 3D ECG variability parameters

R peaks cloud volume was not found to differ significantly between blacks and whites (Table 2). However, T peaks cloud volume and T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio were found to be significantly smaller in blacks. At the same time, the heart rate was slightly but significantly faster in blacks, with accordingly slightly, but significantly shorter QT interval. There were no differences in the HRv and QTv between racial groups. Type of cardiomyopathy was not a significant predictor of T peaks cloud volume in an interquartile regression.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline routine ECG and 3D ECG repolarization lability

| Characteristic | Whites (n=280) | Blacks (n=134) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| R peaks cloud volume of 30 beats median (interquartile range), 103*mV3 | 208(87–496) | 211(92–516) | 0.749 |

| T peaks cloud volume of 30 beats median (interquartile range), 103*mV3 | 21(9–51) | 16(6–35) | 0.038 |

| T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio median (interquartile range) | 0.11(0.06–0.22) | 0.09(0.04–0.15) | 0.002 |

| Heart rate±SD, bpm | 69.0±14.1 | 72.5±14.1 | 0.010 |

| HRv median (interquartile range), bpm2 | 7.4(2.5–20.0) | 8.8(3.3–25.8) | 0.057 |

| Mean QT±SD, msec | 483±63 | 466±65 | 0.030 |

| QTv median (interquartile range), msec2 | 99.0(29–238) | 85.3(21.7–316) | 0.566 |

| QTVI±SD | −0.64±0.55 | −0.68±0.54 | 0.555 |

In both races R peaks cloud volume strongly and significantly correlated with T peaks cloud volume (rs=0.689, p<0.0001). However, racial differences were observed in correlations between 3D and traditional ECG parameters. In whites, R peaks cloud volume significantly correlated with QRS width (rs=0.109, p=0.040) and QTVI (rs=0.169, p=0.031). By contrast, in blacks R peaks cloud volume significantly correlated only with HRv (rs=0.321, p=0.002).

T peaks cloud volume significantly correlated with QRS width (rs=0.206, p=0.0001), HRm (rs=0.175, p=0.0008), and QTv (rs=0.160, p=0.040) in whites, but not in blacks. In both races T peaks cloud volume significantly correlated with the HRv (rs=0.194, p=0.0019). In the multivariate interquartile regression model, which included QRS duration, HRm, HRv and QTVI, QRS duration remained the only significant predictor of R and T peaks cloud volume in whites (β=3546.2;95%CI 549.3–6547.0;p=0.021), as did HRv in blacks (β=858.0; 95%CI 52.4–1663.6;p=0.037).

T/R peaks cloud volume ratio was significantly lower in blacks than whites as determined by both the Student’s t-test (0.12±0.13 vs. 0.15±0.16, p=0.040) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Table 2). Patients with the highest tertile of the T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio were significantly more likely to be white and have inducible VA (Table 3). A trend toward more frequent use of amiodarone, higher QTVI and significantly lower HRv was found in patients with the highest tertile T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio. T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio significantly correlated with QTVI (rs=0.206, p=0.009) in whites. In blacks no correlations were found between T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio and standard ECG metrics.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical outcomes and selected baseline ECG characteristics of patients with the highest and two lower tertiles of the T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio.

| Characteristic | T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio ≤ 0.125 (n=262) | T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio > 0.125 (n=152) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD, y | 59.1±12.2 | 59.9±11.7 | 0.534 |

| Male sex, n(%) | 189(72.1) | 111(73.0) | 0.845 |

| Whites, n(%) | 164(62.6) | 116(76.3) | 0.004 |

| Ischemic CM, n(%) | 136(51.9) | 91(59.9) | 0.117 |

| Baseline LVEF±SD, % | 21.8±8.5 | 22.2±8.9 | 0.625 |

| Complete BBB, n(%) | 14(5.3) | 13(8.6) | 0.202 |

| LVDD±SD, cm | 5.93±0.95 | 6.07±0.97 | 0.333 |

| Beta blockers, n(%) | 252(96.1) | 146(96.1) | 0.450 |

| PTCA and/or CABG history, n(%) | 100(78.7) | 60(72.3) | 0.283 |

| Amiodarone, n(%) | 55(21.0) | 52(34.2) | 0.073 |

| NYHA class III, n(%) | 128(49.0) | 79(52.0) | 0.600 |

| Inducible VT, n(%) | 55(21.0) | 51(33.6) | 0.002 |

| Heart rate±SD, bpm | 68.5±12.1 | 68.3±13.1 | 0.890 |

| HRv median (interquartile range), bpm2 | 7.5(2.8–17.0) | 7.0(2.3–15.9) | 0.016 |

| Mean QT±SD, msec | 482±62 | 481±63 | 0.959 |

| QTv median (interquartile range), msec2 | 70.6(17.6–234.8) | 82.3(22.0–261.2) | 0.620 |

| QTVI±SD | −0.74±0.61 | −0.59±0.49 | 0.064 |

Discussion

In this study we explored a 3D approach in assessment of temporal variability of cardiac signal and showed that a relatively high T peaks cloud volume of 30 consecutive sinus beats, measured as the highest tertile of T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio, is associated with increased risk of VA in patients with structural heart disease and systolic dysfunction. We have found racial differences in 3D repolarization lability, characterized by larger T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio in whites than blacks and different determinants of peaks cloud volume.

Methods of assessment of temporal repolarization lability

QT interval measures the time needed for depolarization and repolarization of all the cells in the ventricular myocardium. Importantly, the end of the T wave in a surface ECG lead does not correspond to the end of ventricular repolarization; instead, it reflects the projection of the ventricular repolarization front onto the associated lead axis. Methodological difficulties, i.e., inaccuracies in the T end determination, the existence of U waves and biphasic T waves, could affect results of QT variability assessment on routine ECGs. VCG has well recognized advantages over routine surface ECG in description of repolarization20: VCG helped to recognize 12-leads QT dispersion as an attribute of T-loop morphology, rather than dispersion of repolarization. It was also demonstrated that the T axis is associated with QT duration20: the more perpendicular the T axis is to the lead axis, the shorter the QT duration is. Classical VCG method considers one averaged heart beat and therefore is not suggested for evaluation of rhythm disorders. In our study we merged VCG with assessment of temporal variability of loops and therefore use the term 3D ECG, but not VCG, to specify this approach. Our finding of relatively high T peaks cloud volume associated with VA agrees with previous works showing increased temporal lability of repolarization as a risk factor for VA.

The beat-to-beat QT variability method of Berger et al.16 showed predictive value in clinical studies13. Recently direct evidence of association between augmented sympathetic activity and the increased QTVI in the heart failure dog model was demonstrated21, suggesting that QTVI could be used as a marker of neurohumoral activation. Interestingly, we have found that combination of QT variability with 3D ECG variability further improves prediction of VA, implying possibility of different mechanisms of increased QT variability and enlarged relative T peaks cloud volume.

Investigators explored various mathematical approaches to characterize temporal QT variability, including QT dynamicity, QT/RR slope22, 23, adaptation dynamics of QT interval in response to HR changes24, independent QT variability25, repolarization scatter 26 that showed significant predictive value, similar to our results. T-loop morphology heterogeneity27 was recently proposed as another method for describing repolarization heterogeneity. Prolonged adaptation of QT interval to HR changes could reflect adverse ion changes (fast adaptation is driven by ICaL and IKs kinetics, whereas slow adaptation - by INaK) that may facilitate VA initiation28.

Our method utilizes a different 3D approach, and yet our results are consistent with previous studies showing association of VA with increased temporal repolarization lability. This consistency confirms the correctness of the concept of temporal lability of repolarization as an important arrhythmogenic factor. Moreover, we showed that some degree of temporal variability of depolarization is also present in patients with structural heart disease and systolic dysfunction. Peaks cloud volume metric accounts for the most extremely different beats in the studied time epoch and does not represent true beat-to-beat variability. Still, the method of volume calculations magnifies considerably extreme beat-to-beat differences that otherwise would be subtle. Rovetti et al.29 recently presented a unifying theory, linking “spark-induced sparks” of the intracellular calcium (Ca) to the whole-cell alternans. Randomness is an important characteristic of individual intracellular Ca sparks. As a result the spatial distribution of myoplasmic Ca changes from beat to beat. Heart failure increases the randomness of Ca release and therefore may increase variability of cardiac signal characteristics.

At the same time, other factors may contribute to the peaks cloud volume metric. Fraction of the 3D peaks variability might be a consequence of the presence of respiratory amplitude modulation. Use of amiodarone might be another factor influencing temporal lability of repolarization. In our study patients with enlarged T/R peaks cloud volume were more frequently on amiodarone. Previously we have shown increased intracardiac repolarization lability in patients on class III antiarrhythmics30, which, however, did not affect its predictive value in primary prevention patients. In our study both R and T peaks cloud volume correlate significantly with QRS width. According to our data, the round shape of the loop is represented by a large, sparse peaks cloud, whereas narrow oval shape of the loop is usually represented as a small, dense peaks cloud. HRv also showed significant correlation with both R and T peaks cloud volumes. In other words, peaks cloud represents a 3D view of both temporal and spatial variability of the heart beats. This idea is consistent with the previous observation of rate-dependency of the T-wave amplitude31. Interestingly, we showed 3D presentation of TWA. However, as we analyzed resting ECG with HRm about 70 bpm, predictive value of TWA was not assessed in our study.

Racial differences in 3D ECG variability

We found no differences in the rate of VA between races. However, we observed significant differences in 3D repolarization lability, which was more pronounced at baseline in whites than blacks. The predictive value of increased T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio was also more evident in whites. The observed higher rate of ischemic cardiomyopathy in whites is an obvious confounding factor in our study. However, type of cardiomyopathy was not a significant predictor of T peaks cloud volume or T/R peaks cloud volumes ratio in interquartile regression.

We have found different traditional ECG parameters associated with peaks cloud volume in blacks and whites. In whites T peaks cloud volume was correlated with QRS width, i.e., more likely wide round QRS and T loops shape, and with QTv. Both these factors are known markers of increased VA risk. However, in blacks T peaks cloud volume was correlated with the HRv only, which if increased is associated with a lower risk of VA. Thus, the 3D repolarization lability portrait overall had more favorable characteristics in blacks. Changes in the autonomic cardiac regulation, either reduced sympathetic or increased vagal tone, or suggested sodium channel polymorphism among blacks32 may provide some explanation for our findings. Even so, further studies are warranted to elucidate the mechanisms of the intriguing racial differences in 3D ECG temporal variability.

Limitations

Appropriate ICD therapy as a surrogate for sudden death may overestimate the frequency of SCA33. Still, recent studies showed that patients after appropriate ICD shocks had higher mortality34. Thus, appropriate ICD therapy may represent accurate estimation of SCA risk. Importantly, as the VA risk stratification guides the decision to implant an ICD, a risk marker that predicts the occurrence of successfully controllable by an ICD rhythm seems more appropriate than a marker that predicts events for which ICD placement would be of no benefit.

PROSE-ICD is an ongoing study and the analysis of racial differences in temporal 3D ECG variability presented here should be considered as preliminary and hypothesis-generating.

Conclusion

Relatively large T peaks cloud volume is associated with increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with structural heart disease and systolic dysfunction. T/R peaks cloud volume ratio is significantly larger in whites than blacks, and it correlates with wider QRS and increased QT variance. The method of 3D temporal lability assessment allows us to obtain new information that may not be available otherwise and warrants further study.

Abbreviations

- VA

ventricular arrhythmia

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- LV EF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- HF

heart failure

- HR

heart rate

- HRv

heart rate variance

- QTv

QT variance

- ICD

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- 3D

three-dimensional

- QTVI

QT Variability Index

- SD

standard deviation

- BBB

bundle branch block

- VCG

vectorcardiogram

- MTWA

microvolt T wave alternans

Footnotes

Registration identification number: NCT00733590

Financial support & Conflict of interest: NIH HL R01 091062 (Gordon Tomaselli), Donald W. Reynolds Foundation (Gordon Tomaselli). Other co-authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1576–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henyan NN, White CM, Gillespie EL, Smith K, Coleman CI, Kluger J. The impact of gender on survival amongst patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators for primary prevention against sudden cardiac death. J Intern Med. 2006;260:467–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Liang L, et al. Sex and racial differences in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators among patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;298:1525–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo AM, Hafley GE, Lee KL, et al. Racial differences in outcome in the Multicenter UnSustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT): a comparison of whites versus blacks. Circulation. 2003;108:67–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078640.59296.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorobiof G, Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W, McNitt S. Effectiveness of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator in blacks versus whites (from MADIT-II) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1383–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell JE, Hellkamp AS, Mark DB, et al. Outcome in African Americans and other minorities in the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Am Heart J. 2008;155:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller MS, Sandor G, Punske B, et al. Estimates of repolarization dispersion from electrocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 2000;102:685–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acar B, Yi G, Hnatkova K, Malik M. Spatial, temporal and wavefront direction characteristics of 12-lead T-wave morphology. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1999;37:574–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02513351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langley P, Di BD, Murray A. Quantification of T wave shape changes following exercise. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1230–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antzelevitch C. T peak-T end interval as an index of transmural dispersion of repolarization. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:555–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haigney MC, Zareba W, Gentlesk PJ, et al. QT interval variability and spontaneous ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tereshchenko LG, Fetics BJ, Domitrovich PP, Lindsay BD, Berger RD. Prediction of Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias by Intracardiac Repolarization Variability Analysis. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2009;2:276–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.829440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haigney MC, Zareba W, Nasir JM, et al. Gender differences and risk of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger RD, Kasper EK, Baughman KL, Marban E, Calkins H, Tomaselli GF. Beat-to-beat QT interval variability: novel evidence for repolarization lability in ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;96:1557–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JM, Blue B, Clancy E, Valeri CR, Cohen RJ. Subtle alternating electrocardiographic morphology as an indicator of decreased cardiac electrical stability. Comput Cardiol. 1985;12:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JM, Clancy EA, Valeri CR, Ruskin JN, Cohen RJ. Electrical alternans and cardiac electrical instability. Circulation. 1988;77:110–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han L, Tereshchenko LG. Lability of R- and T-wave peaks in three-dimensional electrocardiograms in implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmia during follow-up. J Electrocardiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kors JA, van HG, van Bemmel JH. QT dispersion as an attribute of T-loop morphology. Circulation. 1999;99:1458–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccirillo G, Magri D, Ogawa M, et al. Autonomic Nervous System Activity Measured Directly and QT Interval Variability in Normal and Pacing-Induced Tachycardia Heart Failure Dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:840–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couderc JP, Xiaojuan X, Zareba W, Moss AJ. Assessment of the stability of the individual-based correction of QT interval for heart rate. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2005;10:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.00593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cygankiewicz I, Zareba W, Vazquez R, et al. Prognostic value of QT/RR slope in predicting mortality in patients with congestive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1066–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pueyo E, Smetana P, Caminal P, de Luna AB, Malik M, Laguna P. Characterization of QT interval adaptation to RR interval changes and its use as a risk-stratifier of arrhythmic mortality in amiodarone-treated survivors of acute myocardial infarction. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51:1511–20. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.828050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porta A, Tobaldini E, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Montano N. RT variability unrelated to heart period and respiration progressively increases during graded head-up tilt. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1406–H1414. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01206.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segerson NM, Litwin SE, Daccarett M, Wall TS, Hamdan MH, Lux RL. Scatter in repolarization timing predicts clinical events in post-myocardial infarction patients. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couderc JP. Measurement and regulation of cardiac ventricular repolarization: from the QT interval to repolarization morphology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2009;367:1283–99. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pueyo E, Husti Z, Hornyik T, et al. Mechanisms of ventricular rate adaptation as a predictor of arrhythmic risk. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1577–H1587. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00936.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rovetti R, Cui X, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Spark-induced sparks as a mechanism of intracellular calcium alternans in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2010;106:1582–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tereshchenko LG, Fetics BJ, Berger RD. Intracardiac QT variability in patients with structural heart disease on class III antiarrhythmic drugs. J Electrocardiol. 2009;42:505–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Couderc JP, Vaglio M, Xia X, et al. Impaired T-amplitude adaptation to heart rate characterizes I(Kr) inhibition in the congenital and acquired forms of the long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke A, Creighton W, Mont E, et al. Role of SCN5A Y1102 polymorphism in sudden cardiac death in blacks. Circulation. 2005;112:798–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.482760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhar R, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Estes NA, III, et al. Association of prolonged QRS duration with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II) Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:807–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]