Abstract

The genus Schizosaccharomyces is presently comprised of three species, namely S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. japonicus. Here we describe a hitherto unknown species, Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus, named for its preference for growth at lower temperatures than the other fission yeast species. Although morphologically similar to S. octosporus, analysis of several rapidly evolving sequences, including the D1/D2 divergent domain of the large subunit (LSU) rRNA gene, the RNA subunit of Ribonuclease P (RNase P) and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) elements, revealed significant divergence from any previously characterized Schizosaccharomyces strain. Based on phylogenetic analysis of the D1/D2 domain of the LSU rRNA gene S. octosporus is the closest known relative of S. cryophilus with the sequences of the two species differing by 25 nucleotide substitutions (> 4%). Sequencing of the S. cryophilus genome and phylogenetic analysis of all 1:1 protein orthologs confirmed this observation, and together with morphological and physiological characterization supports the assignment of S. cryophilus as a new species within the genus Schizosaccharomyces. The type strain of the new species is NRRL Y-48691T (=NBRC 106824T = CBS 11777T).

Keywords: Keywords fission yeast, D1/D2, RNase P, ITS, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, 454 genome sequence

Introduction

Fission yeasts are unicellular eukaryotes, allocated to the genus Schizosaccharomyces in the phylum Ascomycota. The main unifying feature of this group of yeasts is division by medial fission (mechanism reviewed in Chang & Nurse, 1996). This genus is currently comprised of three species, S. pombe (Linder, 1893), containing the varieties S. pombe var. pombe and S. pombe var. malidevorans (Sipiczki, et al., 1982); S. octosporus (Beijerinck, 1894) and S. japonicus (Yukawa & Maki, 1931), comprised of the variants S. japonicus var. japonicus and S. japonicus var. versatilis (Wickerham & Duprat, 1945). See (Vaughan-Martini & Martini, 1998) for a review of the genus. Several lines of evidence suggest that the evolutionary distance between S. pombe and S. octosporus is shorter than the distance between either of them and S. japonicus. Firstly, the U6 snRNA intron sequence is most divergent in S. japonicus (Frendewey, et al., 1990, Reich & Wise, 1990), as are the sequences of 18S and 26S rRNA (Yamada, et al., 1973). Secondly, while it is possible to create somatic hybrids between S. pombe and S. octosporus (Sipiczki, 1979), no prototrophs were detected when either of these strains was crossed with S. japonicus (Sipiczki, et al., 1982). Furthermore, while both S. pombe and S. octosporus contain cytochrome oxidase (a + a3) and cytochrome c, levels of these two proteins are undetectable in S. japonicus (Sipiczki, et al., 1982). Such evidence refuted the idea that S. octosporus and S. japonicus be grouped together in a separate genus, Octosporomyces, as proposed earlier (Kudriawzew, 1960).

Based upon the physiological differences between S. japonicus and the two other Schizosaccharomyces species Yamada and Banno (1987) proposed that S. japonicus be assigned to a new genus, Hasegawaea. Subsequent genetic examination of rRNA gene sequences (Naehring, et al., 1995, Kurtzman & Robnett, 1998) rejected this notion and S. japonicus has remained in the Schizosaccharomyces genus.

Fission yeasts normally propagate mitotically as haploids, but under conditions of nitrogen starvation sexual union between two haploid cells of opposite mating-types occurs. The first physical step of mating involves cell elongation with the formation of conjugation tubes as a result of extrinsic growth towards pheromones secreted by cells of opposite mating-types (Leupold, 1987). Conjugation between two cells of opposite mating-type is followed by karyogamy to produce a diploid zygote which undergoes meiosis forming four haploid nuclei which are then encapsulated by spore walls. In species that produce eight ascospores (S. japonicus and S. octosporus), meiosis II is followed by a mitotic division resulting in the generation of eight spores (Tanaka & Hirata, 1982).

Since the initial discovery of S. pombe (Linder, 1893), several other species have been described in this genus including S. liquefaciens (Osterwalder, 1924)and S. slooffiae (Kumbhojkar, 1972), but closer examination of nuclearDNA/nuclearDNA reassociation kinetics (Martini, 1991) revealed them to be conspecific with one of the three aforementioned species. Here we describe a new species of fission yeast on the basis of phenotypic differences, genome sequencing and phylogenetic analyses. Based on its preference for growth at lower temperatures than other fission yeasts, we named the new species Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus.

Materials and Methods

Strains and culture media

Strains used in this study were obtained from Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands or the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains utilized in this study.

| Strain name |

|---|

| S. pombe var. pombe CBS 356T |

| S. pombe var. pombe 972 h- ATCC 38366 |

| S. octosporus var. octosporus CBS 371T |

| S. octosporus var. octosporus (formerly S. slooffiae)CBS 6207T |

| S. octosporus var. octosporus CBS 6206 |

| S. japonicus var. japonicus CBS 354T |

| S. japonicus var. versatilis CBS 103T |

| S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T, NBRC 106824T, CBS 11777T |

Sources: CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. S. cryophilus has been deposited at NRRL, Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, Illinois, U.S.A; CBS and NBRC, NITE Biological Resource Center, National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, Chiba, Japan

Strains were propagated on YES (0.5% yeast extract, 3% glucose, 0.01% leucine, 0.01% uracil, 0.01% histidine-HCl, 0.01% adenine, 2% agar) or YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, 2% agar) plates. For sporulation, strains were plated on G25YA (29% glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 1.5 % agar), ME (3% malt extract, 2% agar), ME + 0.4% glucose, PMG (0.3% potassium hydrogen phthalate, 0.415% Na2HPO4.7H2O, 2% dextrose, 1 X salt stock, 1 X vitamin stock, 1 X mineral stock, 2% agar) or SPA (1% potassium diphosphate, 1 X vitamin stock, 3% agar) media. See (Alfa, et al., 1993) for composition of stock solutions.

Microscopy

Liquid cultures were passed through an 18 gauge needle to break up large cell clumps. Samples were imaged using a Zeiss AxioVert microscope with a 63 x 1.4 NA Plan-APOCHROMAT DIC objective. Cell dimensions were measured using AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH).

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was performed as previously described (Baumann & Cech, 2000), except that the final concentration of Zymolyase (US Biological) was increased to 0.6 mg/ml.

PCR amplification of genomic fragments

Genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (Bunch, et al., 2005). The D1/D2 domain of the LSU rRNA gene and the ITS elements were amplified and sequenced using primers in flanking conserved regions. RNase P was amplified using primers complementary to conserved regions of flanking open reading frames based on alignment of the S. pombe, S. japonicus and S. octosporus sequences. The ITS elements were amplified from all species examined using the oligonucleotides BLoli1467 (5’-TCCTAGTAAGCGCAAGTCATCAGC -3’) and BLoli1468 (5’-AATTTGAGCTTTTCCCGCTTCACTCG-3’). The D1/D2 domain of the LSU rRNA gene was amplified according to (Kurtzman & Robnett, 1998). RNase P was amplified using primers BLoli1474 (5’-ACCCAAGTCATYTCAATTTCATGC-3’) and BLoli1475 (5’-GYGCTGGAAAGGGYACACAATGC-3’) for S. japonicus and BLoli1477 (5’-ACCGTTGTAWCCCCAATAAACACC-3’) and BLoli1478 (5’-GTGCTGGWAAGGGTACMCAATGC-3’) for S. cryophilus. PCR reactions (50 μl) contained 1X Pfu reaction buffer (Stratagene), 200 μM dNTPs, 0.5 μM of each primer, 2.5 U PfuTurbo DNA polymerase and 15 ng genomic DNA. In most reactions denaturation at 94°C for 2 min was followed by 30–35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 45 s and 72°C for 3 min. To amplify RNase P from S. japonicus, an annealing temperature of 50°C and an extension time of 5 min were used. Reactions were completed by a final extension at 72°C for 7-10 min. DNA products were subjected to electrophoresis on agarose gels, recovered using the Qiaquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen) and sequenced using the primers listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sequencing primers

| Gene | Species | Oligo sequence (5’–3’) |

|---|---|---|

| D1/D2 | All examined | GCATATCAATAAGCGCAGGAAAAG |

| GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG | ||

| ITS | All examined | TCCTAGTAAGCGCAAGTCATCAGC |

| AATTTGAGCTTTTCCCGCTTCACTCG | ||

| TGAACGCACATTGCGCCTTTGGG | ||

| RNase P | All examined | TCCCAAATCGTAWCCTGTRCCRA |

| GCCGCACATTGCACTAAAAGA | ||

| TAGTGCAATGTGCGGCACCTG | ||

| CAGGCSGAATACGCGTAYAA | ||

| S. japonicus | ACCCAAGTCATYTCAATTTCATGC | |

| GYGCTGGAAAGGGYACACAATGC | ||

| S. octosporus | ACGAGCATATGCTTCAGCCTCTTG | |

| GTGCTGGWAAGGGTACMCAATGC | ||

| S. cryophilus | ACCGTTGTAWCCCCAATAAACACC | |

| GTGCTGGWAAGGGTACMCAATGC |

Sequence retrieval and analysis

RNase P sequences from S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. cerevisiae were obtained from the RNase P database: http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/RnaseP/home.html (Brown, 1999). Flanking open reading frame sequences were obtained from the Broad Institute. RNase P from S. japonicus and S. cryophilus was cloned based on homology in flanking open reading frames. The D1/D2 LSU rRNA gene sequences for S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. japonicus and the ITS sequences for S. pombe and S. japonicus were retrieved from GenBank. The ITS sequences for S. octosporus and S. cryophilus and the D1/D2 region for S. cryophilus were cloned based upon homology to the corresponding S. pombe sequence.

Sequence alignments were performed using Jalview (Waterhouse, et al., 2009) and phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA4 (Tamura, et al., 2007). Saccharomyces cerevisiae was included as outgroup representative. Nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited into GenBank with the following accession numbers: S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T D1/D2: GU470882; S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T RNase P: GU470883; S. japonicus CBS 354T RNase P: GU470884; S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T ITS regions: GU470885; S. octosporus CBS 371T ITS regions: GU470886.

Genome sequencing

Genomic DNA from S. cryophilus was submitted to 454 Life Sciences for whole genome sequencing. A titanium fragment library was made from 5 μg genomic DNA and sequenced on a single 454 run using titanium chemistry. A 3K Long-Tag Paired-End (LTPE) library was made in parallel from the same amount of genomic DNA and sequenced on half of an FLX run. Approximately 1.3 million high quality reads of 400 bp were generated from the titanium run and 700,000 reads were generated from the LTPE FLX run. Quality filtered sequences from the whole genome shotgun fragment library and LTPE library were assembled using the 454 Newbler assembler.

Phenotypic characterization

To determine the relative growth phenotypes for fission yeast strains at different temperatures, liquid cultures (YES and YPD) were diluted to 2 x106 cells. Serial dilutions (1:5) were prepared and 10 μl aliquots were spotted onto YES and YPD agar media. Plates were photographed following incubation at 18, 25, 28, 32 and 36°C for 3 days. Fermentation of carbohydrates was assessed according to standard methods (Yarrow, 1998). Carbon assimilation tests were examined using the ID 32 C test strip (bioMerieux) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Urea hydrolysis was tested on solid medium using BBL Urea Agar prepared slants (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results and Discussion

As part of the characterization of the telomerase RNA subunit (TER1) from fission yeast (Leonardi, et al., 2008, Webb & Zakian, 2008), we amplified and sequenced the TER1 encoding region from genomic DNA samples of over 100 isolates of fission yeast. During this analysis, which will be published elsewhere, we noted a sequence that differed substantially from all others. Closer examination of the original culture (S. octosporus, CBS 7191) revealed the presence of heterogeneous colony morphology on the agarose plate, suggesting that the previously characterized S. octosporus isolate was mixed with another organism. To further investigate the origin of the distinct TER1 sequence we isolated single colonies and prepared genomic DNA for further sequence analysis.

Sequence analysis

To examine sequence differences at specific loci, we sequenced the D1/D2 divergent domain of the LSU rRNA gene, the RNA subunit of Ribonuclease P (RNase P) and the ITS elements, three rapidly-evolving sequences commonly used in phylogenetic analyses (reviewed in Cho, et al., 1998, Haas & Brown, 1998, Kurtzman & Robnett, 1998, Iwen, et al., 2002, Nilsson, et al., 2008). The phylogenetic tree constructed from the D1/D2 nucleotide sequence data using S. cerevisiae as outgroup representative, shows that S. cryophilus clusters with S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. japonicus supporting that it is a member of the Schizosaccharomyces genus (Fig. 1a). It is most closely related to S. octosporus although the two species differ by 25 nucleotide substitutions (>4%) and 3 indels. Given that a nucleotide substitution rate > 1% is indicative of distinct species (Kurtzman & Robnett, 1998), we propose that S. cryophilus represents a previously uncharacterized species. The sequences of all S. octosporus strains examined were identical and there were only one and five differences between the two S. pombe strains and the two S. japonicus strains, respectively, thereby confirming these as conspecific strains. Conspecific strains were omitted from further analyses.

Figure 1.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on sequences of (a) the D1/D2 divergent domains of the LSU rRNA gene and (b) the RNA subunit of RNase P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae was included as outgroup representative. GenBank accession numbers are indicated. Numbers represent the bootstrap values from 1000 replicates (values less than 50% are not shown). Scale bar represents the number of substitutions per nucleotide position.

Phylogenetic analysis of the RNA subunit of RNase P yielded a similar phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1b). Again, S. cryophilus was most closely related to S. octosporus with the sequences of these two species differing by 15 nucleotide substitutions (>5%) and 3 indels.

There was a significant degree of disparity in ITS length between the species examined (Table 3), with the sequence of ITS1 in S. japonicus (183 bp) being over 200 bp shorter than the equivalent region in S. pombe (417 bp). ITS2 length was more uniform with a maximum difference of only 46 bp. Comparison of the S. cryophilus and S. octosporus ITS1 and ITS2 sequences revealed 95 nucleotide substitutions / 66 indels and 84 nucleotide substitutions / 51 indels respectively, further confirming S. cryophilus as a distinct species.

Table 3.

ITS length (bp) in fission yeast species

As an additional step to examine sequence differences between S. cryophilus and other fission yeast species, intact chromosomal DNA was subjected to NotI digestion and subsequent pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. The observed banding pattern in S. cryophilus differed notably from the pattern observed in samples from S. pombe and S. octosporus (Fig. 2), indicative of significant sequence divergence across the genome. It is noteworthy that the digestion patterns of all three S. octosporus strains examined were very similar to each other but distinct from S. cryophilus. S. japonicus was omitted from this analysis as the aforementioned sequence analysis had shown it to be a more distant relative than S. octosporus and S. pombe.

Figure 2.

NotI-digested genomic DNA was subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized on a Typhoon PhosphorImager using a 532 nm laser and 610 BP 30 filter.

Having established profound sequence divergence between S. cryophilus and all previously described species of fission yeast, we surmised that a S. cryophilus genome sequence would constitute a useful resource for the fission yeast community as well as for evolutionary and computational biologists interested in this genus. Genomic DNA was sequenced using 454 Life Sciences’ technology for whole-genome sequencing and the Broad Institute generously agreed to host and annotate a draft sequence on their Schizosaccharomyces group website (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/schizosaccharomyces_group/GenomesIndex.html). Genome annotation and subsequent phylogenetic analysis of 1:1 protein orthologs confirmed that S. cryophilus is most closely related to S. octosporus, with the two species sharing 85% amino acid identity. Amino acid identity between 1:1 orthologs is limited to 66% with S. pombe and 55% with S. japonicus (Brian Haas, Broad Institute, personal communication).

Latin diagnosis of Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus Helston, Box, Tang & Baumann sp. nov

In media liquido YPD in 25°C cellulae sunt spheroidae aut ovoidae (5.25 +/− 0.20 μm x 4.85 +/− 0.10 μm). In agaro YPD post dies quinque at 25°C cultura butyrosa et cremea. Margine undulatis. Multiplicatio non-sexualis fissione. Species homothallica. In agaro malti aut PMG asci cum 1–8 sporis formatur.

Glucosum, maltosum et sucrosum (exigue) fermentantur at non galactosum. Glucosum, maltosum et methyl α-D-glucopyranosidum assimilantur at non galactosum, sucrosum, trehalosum, raffinosum, lactosum, D-xylosum, L-sorbosum, glucosaminum, D-ribosum, L-arabinosum, L-rhamnosum, D-cellobiosum, D-melibiosum, D-melezitosum, glycerolum, erythritolum, D-mannitolum, inositolum, 2-keto- D-gluconicum, acidum D-gluconicum, acidum D-glucuronicum, acidum lacticum, D-sorbitolum, palatinosum, acidum levulinicum nec N-acetylglucosaminum. Non crescit in 0.01% cycloheximido. Urea finditur.

Typus stirps NRRL Y-48691T (= NBRC 106824T = CBS 11777T).

Description of Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus Helston, Box, Tang & Baumann sp. nov

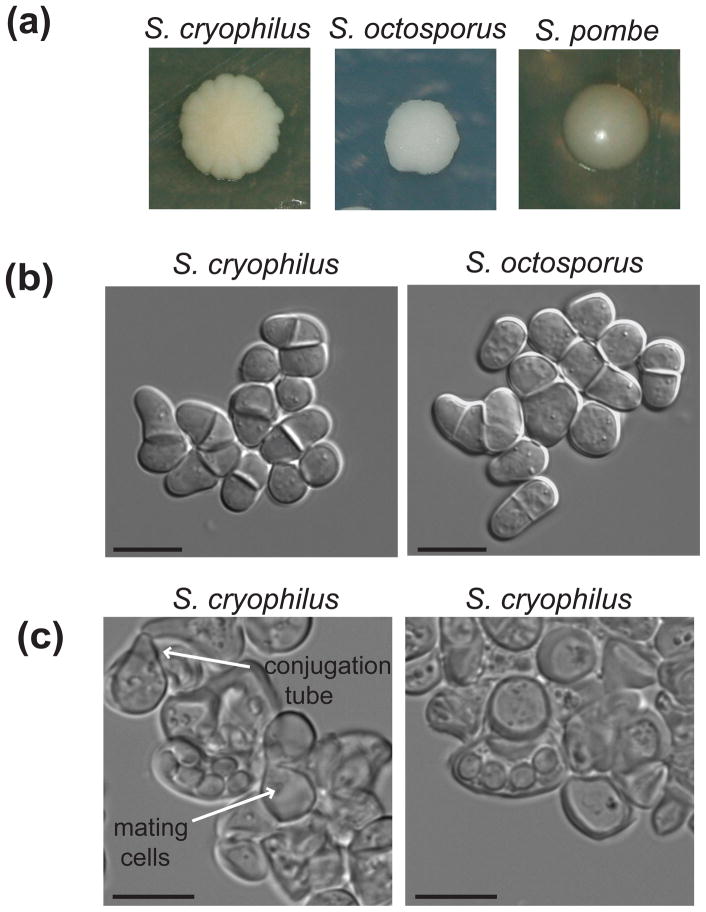

On YPD agar, after growth for 5 days at 25°C, colonies are cream-colored and butyrous with undulate margins (Fig. 3a), in contrast with the smooth rounded appearance of S. pombe colonies and the foam-like appearance of S. octosporus colonies. When propagated in liquid YPD medium at 25°C, cells are rounded and have a high tendency to flocculate (Fig. 3b). The overall morphology is most similar to S. octosporus, but S. cryophilus cells are smaller in both length (5.25 +/− 0.20 μm versus 7.00 +/− 0.34 μm) and width (4.85 +/− 0.10 μm versus 5.68 +/− 0.09 μm). Cells elongate slightly during division which occurs by fission. When plated on PMG or ME media, after 3 days fresh cultures produced 1–8 spores, with tetrads and hexads being most common (Fig. 3c). The ability to sporulate was rapidly lost upon subculturing, as is common in a number of other yeasts (Yarrow, 1998). The observation of conjugation tubes (indicated with arrows in Fig. 3c) suggests that the isolate of S. cryophilus is a homothallic strain.

Figure 3. Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus morphology.

(a) Fission yeast cultures were grown on YES agar plates at 32°C (S. octosporus CBS 371T and S. pombe CBS 356T) or 25°C (S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T) for 3-5 days. (b) S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T and S. octosporus CBS 371T cultures were grown to mid-log phase in YPD and YES media, respectively. Scale bars represent 10 μm. (c) S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T was streaked on PMG or ME agar plates and imaged after 3 days. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

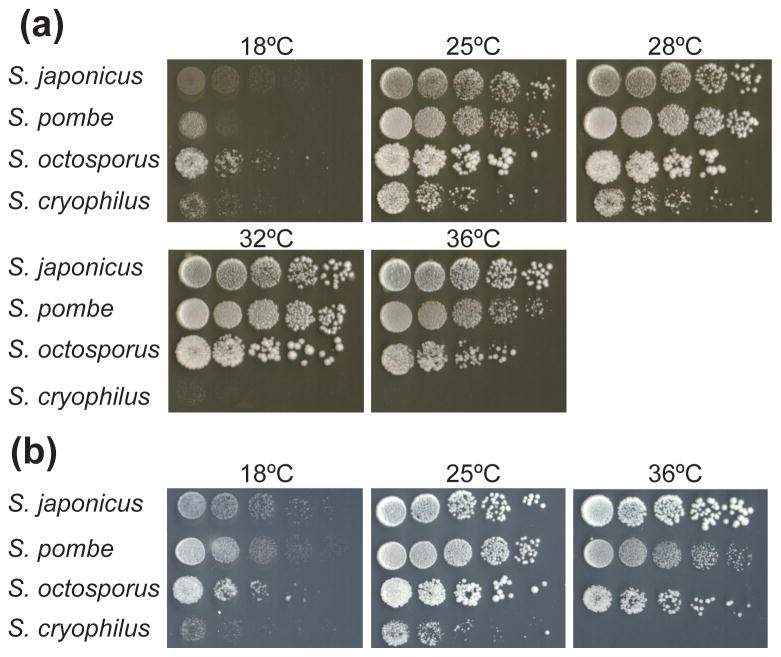

To determine the optimal growth temperature for S. cryophilus, serial dilutions of cells were spotted onto both YES and YPD plates and incubated at various temperatures. While optimal growth of S. japonicus, S. pombe and S. octosporus occurred at 32°C, these three species were capable of growth across the temperature range from 18°C to 36°C. In contrast, growth of S. cryophilus was optimal at 25°C, with little or no growth at higher temperatures (Fig. 4a). Growth of S. cryophilus was slightly better on YPD media (Fig. 4a) than on YES media (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Spotting growth assay of fission yeast strains. Comparison of growth of fission yeast strains S. japonicus CBS 354T, S. pombe CBS 356T, S. octosporus CBS 371T and S. cryophilus NRRL Y-48691T. Cultures of each strain were serially diluted, spotted onto (a) YPD or (b) YES media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days.

Physiological characteristics of S. cryophilus and the three other fission yeast species are presented in Table 4. As observed for S. pombe, S. cryophilus is able to ferment D-glucose, maltose and also sucrose (albeit weakly) but not D-galactose. Use of the ID 32 C test strip revealed that this species is able to assimilate D-glucose, D-maltose and methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (albeit delayed). Most ascomycetous yeasts are unable to hydrolyze urea, Schizosaccharomyces species being an exception. Inoculation of urea agar slants revealed that S. cryophilus is also able to hydrolyze urea, although at a much slower rate than S. pombe. Growth is negative in the presence of 0.01% cycloheximide.

Table 4.

Physiological properties of fission yeast

| Property | S. cryophilus | S. pombe | S. octosporus | S. japonicus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRRL Y- 48691T | CBS 356T | CBS 371T | CBS 354T | |

| Fermentation of carbon compounds | ||||

| D-Glucose | + | + | n/d | +* |

| D-Galactose | - | - | n/d | −* |

| Maltose | + | + | n/d | +* |

| Sucrose | w | + | n/d | +* |

| Assimilation of carbon compounds | ||||

| D-Glucose | + | + | + | + |

| D-Galactose | - | − | − | − |

| L-Sorbose | − | − | − | − |

| Glucosamine | − | − | − | − |

| D-Ribose | − | − | − | − |

| D-Xylose | − | − | − | − |

| L-Arabinose | − | − | − | − |

| L-Rhamnose | − | − | − | − |

| Sucrose | − | + | d | + |

| D-Maltose | + | + | + | − |

| D-Trehalose | − | − | d | − |

| Methyl-α-D - glucopyranoside | d | + | d | − |

| D-Cellobiose | − | − | − | − |

| D-Melibiose | − | − | − | − |

| D-Lactose | − | − | − | − |

| D-Raffinose | − | + | − | + |

| D-Melezitose | − | − | − | − |

| Glycerol | − | − | − | − |

| Erythritol | − | − | − | − |

| D-Mannitol | − | − | − | − |

| Inositol | − | − | − | − |

| 2-Keto-D-Gluconate | − | − | − | − |

| D-Gluconate | − | − | d | − |

| D-Glucuronate | − | − | − | − |

| Lactic acid | − | − | − | − |

| D-Sorbitol | − | − | − | − |

| Palatinose | − | + | d | − |

| Levulinic acid | − | − | − | − |

| N-Acetyl- Glucosamine | − | − | − | − |

| Other tests | ||||

| Cycloheximide | − | − | − | − |

| Urea | d | + | + | + |

data from CBS

d-delayed, w-weak. n/d–not determined

Origin and species designation

S. cryophilus was isolated in our laboratory as a contaminant of the S. octosporus strain CBS 7191 which had been isolated in Taastrup Denmark from the feed of Osmia rufa and deposited by J.P. Skou at the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. While it is unclear whether S. cryophilus cells were present in the original isolate of S. octosporus, we consider this a reasonable possibility for the following reasons: First, to our knowledge no other isolate of S. cryophilus has been described making it unlikely that the S. octosporus culture was contaminated with another strain in our laboratory or elsewhere. Second, the tendency of S. octosporus and S. cryophilus cells to clump together and form mixed colonies favors the possibility that S. cryophilus could have been carried along in the S. octosporus culture until we coincidentally isolated it.

The description of S. cryophilus is based on a single isolate of uncertain origin. While this is unsatisfying from a taxonomic viewpoint, we believe that description of this isolate as a species is justified in light of the substantial sequence divergence from all other known species. Most importantly, description of S. cryophilus makes the organism and the associated sequencing data available to the scientific community for further analysis. It is hoped that identification of additional isolates by others will soon shed more light on the biology of this organism.

The type strain has been deposited at NRRL, Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, IL, U.S.A. as Y-48691T, the Centraal Bureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, Netherlands as CBS 11777T, and at NBRC, NITE Biological Resource Center, National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, Japan as NBRC 106824T.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Stowers Institute Microscopy Center for training and the Molecular Biology Facility for sequencing services. We thank Chad Nusbaum and Brian Haas at the Broad Institute for hosting the S. cryophilus sequence on their web server and for sharing information prior to publication. We also thank Matthias Sipiczki and Nick Rhind for comments on the manuscript and the members of the Baumann lab for helpful discussions. This study was funded by the Stowers Institute. PB is an HHMI Early Career Scientist.

Works Cited

- 1.Alfa C, Fantes P, Hyams J, McLeod M, Warbrick E. Experiments with Fission Yeast. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann P, Cech TR. Protection of telomeres by the Ku protein in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3265–3275. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beijerinck MW. Schizosaccharomyces octosporus, eine achtsporige Alkoholhefe. Zentralblatt Bakteriologie Parasitenkunde. 1894;16:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JW. The Ribonuclease P Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:314. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunch JT, Bae NS, Leonardi J, Baumann P. Distinct requirements for Pot1 in limiting telomere length and maintaining chromosome stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5567–5578. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5567-5578.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang F, Nurse P. How fission yeast fission in the middle. Cell. 1996;84:191–194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho M, Yoon JH, Kim SB, Park YH. Application of the ribonuclease P (RNase P) RNA gene sequence for phylogenetic analysis of the genus Saccharomonospora. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48(Pt 4):1223–1230. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frendewey D, Barta I, Gillespie M, Potashkin J. Schizosaccharomyces U6 genes have a sequence within their introns that matches the B box consensus of tRNA internal promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2025–2032. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas ES, Brown JW. Evolutionary variation in bacterial RNase P RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4093–4099. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwen PC, Hinrichs SH, Rupp ME. Utilization of the internal transcribed spacer regions as molecular targets to detect and identify human fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2002;40:87–109. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.1.87.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudriawzew WI. Die Systematik der Hefen. Akademie-Verlag; Berlin: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumbhojkar MS. Schizosaccharomyces slooffiae Kumbhojkar, a new species of osmophilic yeasts from India. Current Science. 1972;41:151–152. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtzman CP, Robnett CJ. Identification and phylogeny of ascomycetous yeasts from analysis of nuclear large subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA partial sequences. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology. 1998;73:331–371. doi: 10.1023/a:1001761008817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonardi J, Box JA, Bunch JT, Baumann P. TER1, the RNA subunit of fission yeast telomerase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:26–33. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leupold U. Sex appeal in fission yeast. Current Genetics. 1987;12:543–545. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linder P. Schizosaccharomyces pombe n.sp., ein neuer Gährungserreger. Wochenschrift für Brauerei. 1893;10:1298–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martini AV. Evaluation of phylogenetic relationships among fission yeast by nDNA/nDNA reassociation and conventional taxonomic criteria. Yeast. 1991;7:73–78. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naehring J, Kiefer S, Wolf K. Nucleotide sequence of the Schizosaccharomyces japonicus var. versatilis ribosomal RNA gene cluster and its phylogenetic implications. Curr Genet. 1995;28:353–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00326433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson RH, Kristiansson E, Ryberg M, Hallenberg N, Larsson KH. Intraspecific ITS variability in the Kingdom Fungi as expressed in the international sequence databases and its implications for molecular species identification. Evolutionary Bioinformatics. 2008;2008:193–201. doi: 10.4137/ebo.s653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterwalder A. Schizosaccharomyces liquefaciens n. sp., eine gegen freie schweflige Säure widerstandsfähige Gärhefe. Mitt Gebiete Lebensmittelunters Hyg. 1924;15 :5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reich C, Wise JA. Evolutionary origin of the U6 small nuclear RNA intron. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1990;10:5548–5552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sipiczki M. Interspecific protoplast fusion in fission yeasts. Current Microbiology. 1979;3:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sipiczki M, Kucsera J, Ulaszewski S, Zsolt J. Hybridization studies by crossing and protoplast fusion within the genus Schizosaccharomyces Lindner. Journal of General Microbiology. 1982;128:1989–2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka K, Hirata A. Ascospore development in the fission yeasts Schizosaccharomyces pombe and S. japonicus. J Cell Sci. 1982;56:263–279. doi: 10.1242/jcs.56.1.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaughan-Martini A, Martini A. Schizosaccharomyces Lindner. In: Kurtzman CP, Fell J, editors. The yeasts, a taxonomic study. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1998. pp. 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2-A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webb CJ, Zakian VA. Identification and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe TER1 telomerase RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wickerham LJ, Duprat E. A remarkable fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces versatilis nov. sp. Journal of Bacteriology. 1945;50:597–607. doi: 10.1128/JB.50.5.597-607.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada Y, Banno I. Hasegawaea gen. nov., an ascosporogenous yeast genus for the organisms whose asexual reproduction is by fission and whose ascospores have smooth surfaces without papillae and which are characterized by the absence of coenzyme Q and by the presence of linoleic acid in cellular fatty acid composition. Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 1987;33:295–298. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada Y, Arimoto M, Kondo K. Conenzyme Q system in the classification of the ascosporogenous yeast genus Schizosaccharomyces and yeast-like genus Endomyces. Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 1973;19:353–358. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yarrow D. Methods for the isolation, maintenance and identification of yeasts. In: Kurtzman CP, Fell J, editors. The yeasts, a taxonomic study. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1998. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yukawa M, Maki T. Schizosaccharomyces japonicus nov. spec. La Bul Sci Falkultato Terkultura. 1931;4:218–226. [Google Scholar]