Abstract

CD8 T-cell responses constitute a key host defense mechanism against tumor cells and a variety of viral infections, including retroviral infections that lead to acquired immunodeficiency. However, both for tumor cells and for many viral infections, there can be a relative paucity of immunodominant protective CD8 T-cell responses. For retroviruses, their rapid and error-prone replication, coupled with initial CD8 T-cell immunoselection of epitope-variant, retroviral quasi-species, are major impediments to sustaining a protective CD8 T-cell response. To approach this limitation of functional CD8 T-cell epitopes, here we further characterize an underappreciated source of additional T-cell epitopes: cryptic determinants, in particular those encoded in unconventional, alternative reading frames (ARFs). By use of the CD8 T-cell epitope, SYNTGRFPPL, which we have defined as encoded by the +1NT ARF of the gag gene of the LP-BM5 retrovirus that causes murine AIDS, we further characterize the regulation of ARF-epitope expression. Specifically, we examine the translation initiation requirements for production of sufficient epitope for effector CD8 T-cell recognition. Such translation must arise from rare frame-shifting events, making it crucial to understand any other constraints on epitope production, and therefore on the ability of the anti-Kd/SYNTGRFPPL CD8 T cells to protect from LP-BM5 pathogenesis and retroviral load, as we have previously shown. The data herein demonstrate that ARF epitope production depends entirely on conventional AUG-initiated translation, and that the more proximal in-frame ARF AUG is most important. However, maximal epitope production for protective CD8 T-cell lytic function also requires synergy of this initiation codon with a counterpart conventional AUG codon upstream in the same ARF (ORF 2), and with the classic ORF 1 AUG that initiates conventional gag polyprotein translation. These results have implications for the design of ARF-epitope-based vaccines, both to counter retroviral pathogenesis, as well as potentially more broadly, including in tumor systems.

Introduction

Classic CD8 T-cell epitopes are peptide fragments 8–11 amino acids in length, presented in a complex with MHC class I molecules (MHC-I) on the surface of an antigen-presenting, or target, cell. Conventionally produced CD8 cytolytic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes include viral peptide fragments and tumor-associated antigens (32) arising from within the infected/transformed cell. Broadening the spectrum of epitopes available for CTL surveillance is an effective means of maximizing the potential of the CTL response. To this end of increasing the functional T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, “cryptic” epitopes (i.e., epitopes derived from non-traditional sources) have recently been demonstrated to provide an effective antigenic stimulus for the induction of CD8 T-cell responses (2,3,7,9,10,20,22,23,28,29), and in at least one system, the basis for functional protection in vivo by CD8 cytolytic mechanisms (e.g., 13,14,27). Such cryptic epitopes can arise from several non-classical sources, including defective ribosomal products (DRiPs) arising from conventional transcripts (14,34) from unique transcripts generated by either conversion (via mutation) of a normally non-coding intronic sequence, or via exon extension (31), to an immunologically informative translational sequence encoding a peptide (11), or at the post-transcriptional level via incompletely spliced messages (26).

Of greater relevance to this study are cryptic epitopes drawn from non-conventional, atypical translation (5,6,14,21). Most commonly, these unconventional epitopes are thought to be produced by translation commencing from an atypical initiating nucleotide location via initiation codon scanthrough (5,6), doublet decoding (4), initiation from non-AUG codons (19,30), or, most pertinent to this study, those alternative translational products that initiate either from ribosomal frameshifting (6,33) or from an internal ribosome entry site (18,24). In this study, we investigate a cryptic epitope translated from a +1 nucleotide (NT) translational reading frameshift.

Infection with the LP-BM5 retroviral isolate in genetically susceptible C57BL/6 (B6) mice leads to a disease complex termed murine AIDS (MAIDS), which shares many disease attributes with AIDS, including splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, hypergammaglobulinemia, and immunodeficiency leading to subsequent opportunistic infections and eventual generation of terminal neoplasms, particularly B-cell lymphomas (reviewed in 17,25). The LP-BM5 retroviral isolate consists of two types of murine retroviruses: first, replication-competent retroviruses, principally of ecotropic (mouse) host range such as BM5eco, which function as helper viruses; and second, replication-defective genomes (i.e., the BM5def retrovirus), which is the proximal etiological agent causing MAIDS disease. The truncated BM5def genome has full-length encoding capacity for only the gag polyprotein (1,8). Homology between this “pathogenic” BM5def gag and its “non-pathogenic” BM5eco gag counterpart is very high. However, two distinct regions within those sequences, each coding for approximately 25 amino-acid stretches of the gag core proteins p15 and/or p12, show significant deviation and contain most of the variation between BM5eco and BM5def.

Our lab has previously shown that a region of viral gag in the +1 NT alternative reading frame (ARF) of both BM5def (at NT position 652–684) and BM5eco (at a very similar location) codes for a peptide (SYNTGRFPPL), which in disease-resistant H-2d mouse strains constitutes an immunodominant epitope. Thus an ARF-encoded MHC-I (Kd)-presented epitope is expressed during LP-BM5 infection, and is the basis for the protection provided by CD8 CTL in BALB/c mice (13,22,23,29). Indeed, Kd/SYNTGRFPPL-tetramer-specific CD8 T cells, capable both of vigorous cytolysis of BM5def and BM5eco gag-expressing target cells, and of producing IFN-γ in response to peptide exposure, when adoptively transferred post-infection into disease-susceptible BALB/c CD8 knock-out mice, provided essentially full protection from LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis (13). Such protection has recently been shown to predominantly be due to cytolysis by the anti-Kd/SYNTGRFPPL effector CD8 T cells (27).

Our lab has previously published results that suggest that the SYNTGRFPPL epitope might theoretically be generated from either of two potential alternative (but conventional) AUG initiation codons in the +1 NT open reading frame (ORF 2). These ORF 2 AUG sequences are each downstream (at NT positions 158–160 and 647–649, respectively) from the start site for the classic ORF 1 (NT 1–3) that encodes the structural gag polyprotein. Termed initiation codons ORF 2A and ORF 2B, these start sites have been shown to be translationally active and able to encode translational products of 193 AA and 30 AA, respectively, in length (12). In this latter study, our lab prepared BM5 def gag constructs in which the gene for eGFP was inserted downstream of the SYNTGRFPPL-encoding sequences (12). Within this context, site-directed mutagenesis of the start codon(s) in the alternative reading frame, but with no disruption of the coding potential for the primary open reading frame (ORF 1), showed that both ORF 2A and ORF 2B are functional and lead to expressed translational products. Mutation of either the ORF 2A or ORF 2B start codons in the BM5 def virus blocked induction of MAIDS in disease-susceptible B6 mice: both the activational and immunosuppressive parameters of disease were abrogated. Thus the ORF 2A and ORF 2B translational products are necessary for viral pathogenesis.

The ORF 2B AUG was originally defined as immunologically functional in the various BM5def mini-gene constructs assembled for the purpose of fine mapping the epitope (23). Thus, the ORF 2B AUG was found to be both necessary and sufficient, as compared to an engineered ORF 1 AUG, in mini-gene constructs, to drive the expression of SYNTGRFPPL for CD8 effector CTL recognition (23). Based on these functional results, and if eGFP expression and viral pathogenesis data correlate with production of the cryptic epitope in this +1 NT reading frame, then, by extrapolation, we predict that the SYNTGRFPPL epitope may be produced from the ARF translational products that correspond to the ORF 2A and/or ORF 2B initiation codons in full-length BM5def gag polyprotein.

In the present study, we further characterize the role of the start codons embedded in the +1 ARF of the BM5def virus. In particular, we address the relative importance of each start codon of this ORF2 for the production of sufficient Kd-presented SYNTGRFPPL for efficient CD8 CTL recognition. Further, we question whether there is an interplay between the start codon in the “primary” reading frame and one or both of the ORF2A/ORF2B initiation codons. To address these and related questions, our overall approach was to employ a series of full-length BM5def gag constructs in a common vaccinia virus vector. The constructs contained varying mutations in the start codons within the primary reading frame (ORF 1), and/or the alternative reading frame(s) (ORF 2A/ORF 2B). These mutated constructs were utilized to infect target cells to assess their recognition by Kd/SYNTGRFPPL-specific BALB/c CD8 CTL, using lysis assays since we have recently shown that the in vivo protective CTL effector mechanism is due to the cytolytic activity of the CTL (27).

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male BALB/c mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (Frederick, MD), maintained at the Dartmouth Medical School Animal Resource Center (Lebanon, NH), and employed at 6–10 wk of age.

Cell lines

P815B cells, a generous gift from Dr. Jack Bennink (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID]/National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD), were maintained by passage in vitro in RPMI 1640 containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (30 μg/mL), streptomycin (20 mg/mL), L-glutamine (2 mM), gentamicin (33 μg/mL), and β-mercaptoethanol (50 μM).

Recombinant viruses

Recombinant viruses were constructed as previously described (22). Briefly, pSC65 shuttle vector and the Western Reserve isolate of vaccinia virus (designated as wild-type [WT] vaccinia) were generously provided by Dr. Bernard Moss (NIAID/NIH). A molecular clone for WT BM5def, p127/A1, generously provided by Dr. Sisir Chattaopadhyay (NCI/NIH), was used to generate the BM5defORF 2AAUGmut or BM5defORF 2BAUGmut mutant viruses. To create these and other mutant constructs, QuickChange® kits from Stratagene (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) were used for site-directed mutagenesis. The strategies used to generate these mutations were described in detail previously (12). Briefly, the primers used to generate the BM5defORF 2AAUGmut (ΔORF 2A) were 5′-CCACTAGACGGTACTTTTAATTTAGAC and 3′-AATGTCTAAATTAAAAGTACCGTCTAG. To generate the BM5def ORF 2BAUGmut mutant (ΔORF 2B), the primers used were 5′-GTATTGTAACTGACCGTTACCCCCCAAACG and 3′-CGTTTGGGGGGTAACGGTCAGTTACAATAC. As a control, mutation of the BM5def ORF 1 AUG (ΔORF 1) was accomplished via similar site-direct mutagenesis (12).

Generation of cytolytic T effector cells

Six- to 10-wk-old BALB/c mice were immunized IP with 3 × 107 pfu of BM5def gag-expressing vaccinia virus (dG-Vac) and housed in isolation for a period of 3 wk. The mice were then euthanized and the spleens removed. The spleens were processed to a single-cell suspension, and red blood cells were lysed. The cells were resuspended in 10 mL sensitization media and transferred to 25-cm2 flasks. To generate effector T cells (CTL) 1 μg SYNTGRFPPL synthetic peptide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the medium. Alternatively, as controls, parallel cultures did not contain peptide, or were re-stimulated with medium containing (2 × 107 pfu) the empty vaccinia vector (65-Vac) to generate Vac-specific CTL effectors. These Vac-specific CTL were routinely employed as positive controls to ensure that the target cells were equivalently infected by the various recombinant Vac vectors. Since this was the case, these data are not included as presented data. The cultures were fed on day 3 with 5 mL sensitization media; on day 6, 5 mL of sensitization media was replaced with 5 mL sensitization media containing IL-2 (final concentration 15 U/mL). Bulk cytolytic effectors were harvested and utilized in 51Cr-release assays on day 6 or 9. The D7 line of Kd/SYNTGRFPPL specificity was derived from polyclonal BALB/c effector CTL, was maintained by culture in IL-2-containing medium with periodic antigen stimulation, as has been previously described (23).

Infection of target cells

P815B target cells (1–2 × 106) were incubated with shaking for 1 h at 37°C in a volume of 500 μL of a balanced salt solution (BSS) containing 0.1% BSA, the appropriate vaccinia virus construct at an MOI of 20:1, 200 ng/mL SYNTGRFPPL peptide, or BSS/BSA alone. The cells were then suspended in 10 mL of sensitization media (RPMI containing 30 μg/mL penicillin, 20 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 33 μg/mL gentamicin, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, and 10% FCS), and incubated in a Petri dish for an additional 3 h prior to 51Cr labeling.

Chromium release assay

P815B target cells (1–2 × 106) were resuspended in 75 μL FCS and 100 μL [51Cr] sodium chromate (Perkin-Elmer, Shelton, CT), and were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were then washed 2 × in assay medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% calf serum, 30 μg/mL penicillin, and 20 mg/mL streptomycin), counted, and plated (at 5 × 104 to 1 × 105 cells/mL) in 96-well V-bottom plates, together with serially diluted effector cells to achieve a final volume of 200 μL. The plates were incubated for 4–6 h at 37°C, and then centrifuged. Then 100 μL of cell-free supernatant was harvested and read on a gamma counter (1470 Wizard; Perkin-Elmer) for 51Cr activity. Percent specific lysis was determined using the formula ((a – b)/c) × 100, where a is the experimental counts per minute (cpm) released by target cells incubated with effector cells, b is the cpm released by target cells incubated alone (spontaneous release), and c is the total cpm incorporated into target cells. The level of spontaneous release was consistently <15%. Delta lysis values, shown in Figs. 1B, 2, and 3 obtained by normalizing for background CTL activity (i.e., SYNTGRFPPL peptide delta values were obtained by a – b, where a is the lysis of CTL versus SYNTGRFPPL-pulsed P815B targets, and b is the lysis of CTL versus mock-pulsed P815B targets; and recombinant-vaccinia delta values, where a is the lysis of CTL versus the relevant recombinant vaccinia-infected P815B target, and b is the lysis of CTL versus 65-Vac [empty vaccinia] vector-infected P815B target cells).

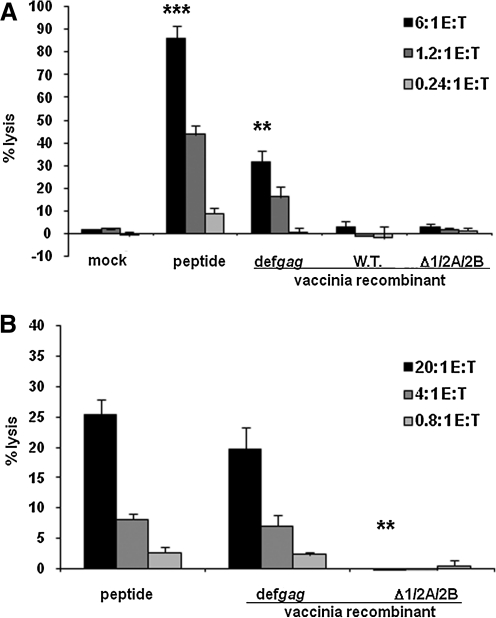

FIG. 1.

The dependence of functional ORF 2 epitope expression on conventional AUG-initiating codons. Cytolytic activity was assessed by standard 51Cr-release assays with effectors: (panel A) a D7 CD8+ cloned line, or (panel B) polyclonal CTL, each with anti-Kd/SYNTGRFPPL specificity. P815B target cells were preincubated with either medium, SYNTGRFPPL peptide, wild-type (WT) vaccinia virus, or vaccinia virus vectors encoding def gag constructs that were either intact or triply mutated at AUG sites ORF 1, ORF 2A, and ORF 2B. The data depicted are representative of four independent experiments with similar patterns of results. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. Comparisons of the levels of percent target cell lysis by the Student's t-test included the following experimental groups: A, mock versus peptide (***p = 0.001); def gag (**p = 0.013); B, peptide versus 1/2A/2B (**p = 0.013).

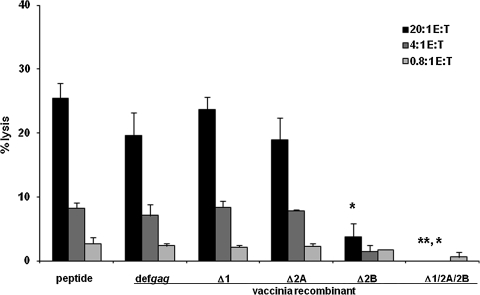

FIG. 2.

ORF 2 epitope production sufficient for CTL recognition and lysis is mainly dependent on an intact epitope-proximal ORF 2B AUG-initiating codon. Cytolytic activity was assessed by standard 51Cr-release assays with polyclonal effector CTL with anti-Kd/SYNTGRFPPL specificity. P815B target cells were preincubated with either SYNTGRFPPL peptide, or recombinant vaccinia vectors encoding def gag constructs that were either intact or mutated at either a single or triple locations so as to be functionally deleted for translation initiation at AUG sites for ORF 1, ORF 2A, and ORF 2B. The data depicted are representative of the pattern of similar results obtained from a total of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. Comparisons of the levels of percent target cell lysis by the Student's t test include the following experimental groups: peptide versus Δ2B (*p = 0.035); peptide versus Δ1/2A/2B (**p = 0.0130); and Δ2B versus Δ1/2A/2B (*p = 0.021).

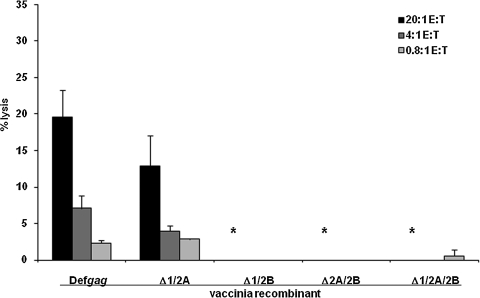

FIG. 3.

CD8 CTL recognition and target cell lysis, as assessed by doubly- and triply-mutant AUG constructs, depends on the ORF 2B AUG, but the ORF 1 and/or ORF 2A AUG start codons cooperate with the ORF 2B AUG for maximal functional epitope expression. Cytolytic activity was assessed by standard 51Cr-release assays using polyclonal effector CTL with anti-Kd/SYNTGRFPPL specificity. P815B target cells were preincubated with recombinant vaccinia vectors encoding def gag constructs that were either intact, or with a series of the various double or triple mutations at AUG sites for ORF 1, ORF 2A, and ORF 2B. The data depicted are representative of the pattern of similar results obtained from a total of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. Comparisons of the levels of percent target cell lysis by the Student's t-test include the following experimental groups: def gag versus Δ1/2B (*p = 0.025); Δ2A/2B (*p = 0.029); Δ1/2A/2B (*p = 0.023).

Results and Discussion

To validate the overall approach of site-directed mutagenesis of AUG initiation codons in the retroviral gag gene as a means to investigate the requirements for effector CTL recognition, a monospecific cloned CD8 CTL line, D7, was first employed (Fig. 1A). As expected, D7 showed robust and highly statistically significant (p = 0.001) lysis of synthetic SYNTGRFPPL-pulsed histocompatible target cells, including at low E:T ratios, which were selected so as to also provide significant (p = 0.013) lysis of target cells infected with a Vac construct encoding the intact BM5def gag gene in the “linear” range (≤30% specific lysis) of the cytolysis curve. As a specificity control target cells pre-infected with WT vaccinia virus were essentially not lysed by these CTL. When the target cells were pre-infected with a construct encoding a BM5def gag in which all three AUG initiation codons were mutated so as to be non-functional for both ORF 1 and ORF 2 translational frames (Δ1/2A/2B), essentially no lysis was also observed (i.e., there was no statistically significant difference from the target cells infected with a Vac construct not encoding SYNTGRFPPL [“mock infected”]). Thus, the system was justified as being appropriate for further investigation, and epitope production at levels sufficient for effector CTL recognition was fully dependent on the known AUG start codons in gag.

Polyclonal CTL sources of anti-Kd/SYNTGRFPPL specificity were next employed as a more physiological source of CTL to be assessed in the rest of the study. Again, the anti-retroviral CTL readily lysed target cells either presenting synthetic SYNTGRFPPL peptide, or pre-infected with the construct encoding intact BM5def gag. But there was little or no lysis (p = 0.013) of target cells infected with the construct encoding the triply-AUG-mutated gag gene (Fig. 1B), again indicating conventional usage of AUG initiation codons for expression of the precursors containing the epitope.

We next assessed the relative roles the ORF 1, ORF 2A, and ORF 2B AUG codons played in initiating the translation of gag products as a source of SYNTGRFPPL for expression at levels sufficient for recognition and lysis by polyclonal anti-retroviral CTL (Fig. 2). Compared to the essential ablation of CTL recognition when all three AUGs were mutated (p = 0.013), mutation of the ORF 1 AUG by itself had little effect; in this particular experiment, if anything, lysis levels were only slightly, and not statistically significantly, higher (and this slight trend was not a consistent finding in repeat experiments). A single mutation of only the ORF 2A AUG also led to either little or no effect (Fig. 2), or only a slight decrease (in each of two repeat experiments), in lysis levels. The small differences in the lysis of the positive control, peptide pulsed or def-gag-infected, targets versus the Δ1 or Δ2A AUG constructs were not statistically significant (Fig 2). In contrast, a single mutation of the ORF 2B AUG, which is most proximal to the beginning of the NT sequences encoding SYNTGRFPPL (i.e., with only one AA intervening), dramatically inhibited lysis (p = 0.035). This result indicated that initiation at the ORF 2B AUG was the single most important necessary element of the translational mechanism for epitope production. However, consistently, mutation of the ORF 2B AUG did not completely abrogate SYNTGRFPPL production as measured by specific CTL recognition, both in the experiment shown in Fig. 2 and in all three repeat experiments. These modest, but significant (p = 0.021), levels of lysis of target cells expressing a BM5def gag with only the ORF 1 and ORF 2A AUG initiation codons intact suggested that these translation sites might also have some importance, alone or in combination, in the production of recognizable levels of SYNTGRFPPL by epitope-specific CD8 CTL.

To further investigate the possible involvement of the ORF 1 and/or ORF 2A AUGs in the absence of the ORF 2B AUG, and the converse questions of whether the ORF 2B AUG on its own is sufficient for SYNTGRFPPL expression as measured by CTL recognition, we constructed a series of all double-mutant permutations (Fig. 3). Both double mutations of gag involving mutation of ORF 2B (i.e., ΔORF 1/ORF 2B and ΔORF 2A/ORF 2B), when delivered into target cells, led to little or no lysis (p = 0.025 and p = 0.029, respectively) in repeat experiments, similarly to the results obtained with the triply-mutant gag. In contrast, the gag construct with only an intact ORF 2B AUG initiation codon (ΔORF 1/2A) lead to CTL recognition and lysis at a level somewhat lower (about 30%) than that of targets expressing intact BM5def gag (Fig. 3). Although this was not a statistically significant difference in Fig. 3, this trend toward a decrease was observed in repeat experiments. This trend of partially decreased lysis of Δ1/2A-expressing targets appeared to be greater than the modest amount of ORF 2B AUG-independent lysis observed with the Δ2B construct observed in Fig. 2, which would have been due there to translation of ORF 2 in an ORF 1- and/or ORF 2A-dependent manner. These results of Figs. 2 and 3 taken together suggest that while the ORF 2B AUG is sufficient to initiate most of the functional epitope production necessary for CTL recognition, initiation at the ORF 2B AUG requires the co-presence of either the ORF 1 or the ORF 2A AUG for full epitope production resulting in maximal levels of CTL lysis. While other more complicated interpretations may be possible, it seems clear that the ORF 2A AUG codon is unable individually to initiate detectable functional SYNTGRFPPL expression, and together with the ORF 1 AUG may mediate only minor expression, despite their abilities to function cooperatively with the ORF 2B AUG to achieve sufficient epitope expression for maximal CTL recognition and lysis.

These results are of interest in attaining a better understanding of the regulation of expression of ARF epitopes for robust CTL responses, and thus an expansion of the CD8 T-cell functional repertoire. The dominance of the ORF 2B-initiating AUG over its ORF 2A counterpart was somewhat surprising, as both of these AUGs exists in the context of a Kozak consensus sequence that can be rated as at least “strong” for translation (21,23). As a likely explanation, the proximity of the ORF 2B AUG to the SYNTGRFPPL-encoding sequence, at only 1 codon away, may be most important. However, we have not discerned any compelling sequence evidence for an internal ribosome entry site upstream of the ORF 2B AUG (23, and unpublished observations), such that the basis for this differential ability of the ORF 2B-initiating AUG most likely still depends on a frameshift event. Perhaps the increased distance of the ORF 2B AUG from the ORF 1 AUG, relative to the distance between the ORF 1 and ORF 2A AUGs, simply allows more opportunities for rare and random net frameshift(s) from ORF 1 to ORF 2. In contrast, a shift from ORF 1 to ORF 2 that could be captured by the ORF 2A AUG would have to be maintained in the ORF 2 frame over the long distance between the ORF 2A AUG site to the actual ORF 2 SYNTGRFPPL-encoding site for functional epitope expression.

These inferences may have broader implications for the manipulation of sources of CD8 T-cell epitopes to promote better responses to pathogens. By definition, ARF epitopes arise only from rare translational events, and hence may be present in relatively limiting amounts, compared to standard (ORF 1) pathogen-reading frames that encode substantial levels of pathogen structural proteins. Despite this inherent limitation, a number of anti-ARF epitope responses have now been defined. In the present MAIDS system we have shown that the ORF2/SYNTGRFPPL-specific CD8 T-cell response is the basis for protection in H-2d mice resistant to LP-BM5 retroviral pathogenesis (13,22,23,29), via CD8 T-cell cytolytic mechanisms (27). Thus, the SYNTTGRFPPL epitope readily serves not only as a target epitope for an effector CTL response, but also as an immunogenic epitope to induce a protective response, even after normal retroviral infection (22,23). Perhaps this is a relatively unique ability that depends on the epitope-proximal position of the dominant ORF 2B AUG-initiation codon. It may be that generally in other systems ARF epitope production is sufficiently limited, due to suboptimal epitope location relative to ARF translation initiation, that this limitation cannot be overcome by the inherent sensitivity of the TCR, particularly at the more stringent level of CTL induction. In these cases the engineering of an initiating ARF AUG closely upstream to the natural epitope sequence, taking care not to alter the coding information of the primary ORF, may allow for increased levels of expression of the ARF epitope to expand the functional CD8 T-cell repertoire.

In addition, to the extent that the NT sequence for the ARF epitope is located in an overlapping reading frame relative to the primary ORF that encodes an essential pathogen protein domain, there may be strong selective pressures to maintain the coding sequence of both the primary reading frame, and unwittingly, the ARF epitope, in particular due to the offset of the two reading frames inherent in their frame-shifted relationship. Thus, it may be relatively difficult for pathogen epitope mutations to be compatible with maintenance of pathogen viability. Indeed, in the present system the ORF 2 SYNTGRFPPL epitope resides in an area where both the ORF 1 (15,16) and the ORF 2 (12) reading frames are critical for viral pathogenesis by the LP-BM5 BM5def component virus. In particular, we have shown that both intact ORF 2A and ORF 2B AUG codons of the BM5def gag gene are necessary for LP-BM5 retroviral pathogenesis, although viral load is essentially unaffected. These considerations have obvious ramifications for the choices of specific ARF epitopes and the adjacent positioning of ARF-initiating AUG start sites with favorable Kozak consensus sequences to engineer these sequences optimally as a general approach to creating better vaccines. These concepts may apply to both prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines, the latter when there is a particular need due to pathogen evasion of conventional epitope responses, such as is commonly seen in HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Melanie Rutkowski, Meghan Brennan, Darshan Sappal, Amy Campopiano, and Shannon Baker for all of their helpful discussions and technical assistance.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant CA50157. The Dartmouth Medical School irradiation facilities were the generous gift of the Fannie Rippel Foundation and are partially supported by NIH core grant CA23108 for the Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Aziz DC. Hanna Z. Jolicoeur P. Severe immunodeficiency disease induced by a defective murine leukemia virus. Nature. 1989;338:505–508. doi: 10.1038/338505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain C. Parroche P. Lavergne JP, et al. Memory T-cell-mediated immune responses specific to an alternative core protein in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:10460–10469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10460-10469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu A. Steele R. Ray R. Ray RB. Functional properties of a 16 kDa protein translated from an alternative open reading frame of the core-encoding genomic region of hepatitis C virus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2299–2306. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce AG. Atkins JF. Gesteland RF. TRNA anticodon replacement experiments show that ribosomal frameshifting can be caused by doublet decoding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5062–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullock TN. Eisenlohr LC. Ribosomal scanning past the primary initiation codon as a mechanism for expression of CTL epitopes encoded in alternative reading frames. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1319–1329. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullock TN. Patterson AE. Franlin LL. Notidis E. Eisenlohr LC. Initiation codon scanthrough versus termination codon readthrough demonstrates strong potential for major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted cryptic epitope expression. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1051–1058. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caardinaud S. Moris A. Fevrier M, et al. Identification of cryptic MHC I-restricted epitopes encoded by HIV-1 alternative reading frames. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1053–1063. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chattopadhyay SK. Morse HC., III Makino M. Ruscetti SK. Hartley JW. Characteristics and contributions of defective, ecotropic and mink cell focus-inducing viruses involved in a retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome of mice. J Virol. 1991;65:4232–4241. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4232-4241.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W. Calvo PA. Malide D, et al. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nature Med. 2001;7:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W. Bennink JR. Yewdell JW. Systematic search fails to detect immunogenic MHC class I-restricted determinants encoded by influenza A virus non-coding sequences. Virology. 2003;305:50–54. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulie PG. Lehmann F. Lethe B. Herman J. Lurquin C. Andrawiss M. Boon TA. Mutated intron sequence codes for an antigenic peptide recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7976–7980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaur A. Green WR. Role of a cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte epitope-defined, alternative gag open reading frame in the pathogenesis of a murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome. J Virol. 2005;79:4308–4315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4308-4315.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho O. Green WR. Cytolytic CD8+ T cells directed against a cryptic epitope derived from a retroviral alternative reading frame confer disease protection. J Immunol. 2006;176:2470–2475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho O. Green WR. Alternative translational products and cryptic T cell epitopes: expecting the unexpected. J Immunol. 2006;177:8283–8289. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang M. Hanna Z. Jolicoeur P. Mutational analysis of the murine AIDS-defective viral genome reveals a high reversion rate in vivo and a requirement for an intact PR60gag protein for efficient induction of disease. J Virol. 1995;69:60–68. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.60-68.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang M. Jolicoeur P. Myristylation of Pr60gag of the murine AIDS-defective virus is required to induce disease and notably for the expansion of its target cells. J Virol. 1994;68:5648–5655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5648-5655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jolicoeur P. Murine acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (MAIDS): an animal model to study the AIDS pathogenesis. FASEB J. 1991;5:2398–2405. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.10.2065888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majacek DG. Sarnow P. Internal initiation of translation mediated by the 5’ leader of a cellular mRNA. Nature. 1991;353:90–94. doi: 10.1038/353090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malarkannan S. Horng T. Shih PP. Schwab S. Shastri N. Presentation of out-of-frame peptide/MHC class I complexes by a novel translation initiation mechanism. Immunity. 1999;10:681–690. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maness NJ. Valentine LE. May GE, et al. AIDS virus specific CD8+ T lymphocytes against an immunodominant cryptic epitope select for viral escape. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2505–2512. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayrand SM. Green WR. Non-traditionally derived CTL epitopes: exceptions that prove the rules? Immunology Today. 1998;19:551–556. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayrand SM. Healy PS. Torbett BE. Green WR. Anti-gag cytolytic T lymphocytes specific for an alternative translational reading frame-derived epitope and resistance versus susceptibility to retrovirus-induced murine AIDS in F1 mice. Virology. 2000;272:438–439. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayrand SM. Schwarz DA. Green WR. An alternative translational reading frame encodes an immunodominant retroviral CTL determinant expressed by an immunodeficiency causing retrovirus. J Immunol. 1998;160:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBratney S. Chen CY. Sarnow P. Internal initiation of translation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:961–965. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morse HC., 3rd Chattopadhyay SK. Makino M. Fredrickson TN. Hugin AW. Hartley JW. Retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency in the mouse: MAIDS as a model for AIDS. AIDS. 1992;6:607–621. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins PF. El-Gamil M. Li YF. Fitzgerald EB. Kawakami Y. Rosenberg SA. The intronic region of an incompletely spliced gp100 gene transcript encodes an epitope recognized by melanoma-reactive tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutkowski MR. Ho O. Green WR. Defining the mechanism(s) of protection by cytolytic CD8 T cells against a cryptic epitope derived from a retroviral alternative reading frame. Virology. 2009;390:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwab SR. Li KC. Chulho K. Shastri N. Constitutive display of cryptic translation products by MHC class I molecules. Science. 2003;301:1367–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.1085650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarz DA. Green WR. CTL responses to the gag polyprotein encoded by the murine AIDS defective retrovirus are strain dependent. J Immunol. 1994;153:436–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shastri N. Nguyen V. Gonzales F. Major histocompatibility class I molecules can present cryptic translation products to T cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1088–1091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uenaka A. Hirano Y. Hata H, et al. Cryptic CTL epitope on a murine sarcoma Meth A generated by exon extension as a novel mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170:4862–4868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Pel A. Van der Bruggen P. Coulie PG, et al. Genes coding for tumor antigens recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 1995;145:229–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss RB. Dunn DM. Atkins JF. Gesteland RF. Slippery runs, shifty stops, backward steps, and forward hops: −2, −2, +1, +2, +5, and +6 ribosomal frameshifting. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:687–693. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yewdell JW. Anton LC. Bennink JR. Commentary: defective ribosomal products (DRiPs): a major source of antigenic peptides for MHC class I molecules. J Immunol. 1996;157:1823–1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]