Abstract

Introduction

Non-unions of the forearm often cause severe dysfunction of the forearm as they affect the interosseus membrane, elbow and wrist. Treatment of these non-unions can be challenging due to poor bone stock, broken hardware, scarring and stiffness due to long-term immobilisation.

Method

We retrospectively reviewed a large cohort of forearm non-unions treated by using a uniform surgical approach during a period of 33 years (1975–2008) in a single trauma centre. All non-unions were managed following the AO-principles of compression plate fixation and autologous bone grafting if needed.

Patients

The study cohort consisted of 47 patients with 51 non-unions of the radius and/or ulna. The initial injury was a fracture of the diaphyseal radius and ulna in 22 patients, an isolated fracture of the diaphyseal ulna in 13, an isolated fracture of the diaphyseal radius in 5, a Monteggia fracture in 5, and a Galeazzi fracture-dislocation of the forearm in 2 patients. Index surgery for non-union consisted of open reduction and plate fixation in combination with a graft in 30 cases (59%), open reduction and plate fixation alone in 14 cases (27%), and only a graft in 7 cases (14%). The functional result was assessed in accordance to the system used by Anderson and colleagues.

Results

Average follow-up time was 75 months (range 12–315 months). All non-unions healed within a median of 7 months. According to the system of Anderson and colleagues, 29 patients (62%) had an excellent result, 8 (17%) had a satisfactory result, and 10 (21%) had an unsatisfactory result. Complications were seen in six patients (13%).

Conclusion

Our results show that treatment of diaphyseal forearm non-unions using classic techniques of compression plating osteosynthesis and autologous bone grafting if needed will lead to a high union rate (100% in our series). Despite clinical and radiographic bone healing, however, a substantial subset of patients will have a less than optimal functional outcome.

Keywords: Non-union, Radius, Ulna, Internal fixation, Forearm

Introduction

Compression plate-and-screw fixation of diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna in adults has been common practice since the late 1950s. Large series have shown this technique to be straightforward with a low complication rate [1–6]. Controversies focused on bone grafting for acute fractures [7–10], the type and length of the plate [5, 11, 12], and the risk of refracture after plate removal [13–16]. Benefits of plate-and-screw fixation are the ability for anatomic and secure reconstruction allowing early motion. Complications of open reduction and internal fixation of forearm function are infection, malunion, non-union, nerve injury, compartment syndrome, bleeding, formation of a synostosis, and limited function [6].

Typical rates reported for forearm non-unions in large cohort studies range between 2 and 10% [1, 5, 7, 8, 17–20]. A diaphyseal forearm non-union is disabling as it effects not only the forearm but also the elbow and wrist. Failure to reconstitute the exact relation between radius and ulna will affect the proximal and distal joints, limiting the ability to place the hand in space [21]. Most often the non-union has a multifactorial cause combining fracture characteristics (e.g. low vs. high energy impact, comminution, location, soft tissue damage, open vs. closed), patient characteristics (age, co-morbidities) as well as surgeon-dependent causes (surgical technique and strategy).

We retrospectively reviewed a large cohort of forearm non-unions in adults treated during a period of 33 years (1975–2008) in a single trauma centre. We present their uniform surgical approach, their functional results and rates of union as well as additional surgery and complications.

Patients and methods

All patients treated in our centre for diaphyseal forearm non-unions during the 24-year period between 1975 and 1999 formed the initial cohort. They were extracted from an AO-database into which all patients for fracture care at our hospital were entered during that time. On average, 21 patients per year were treated for diaphyseal fractures of the forearm. The number of patients that was treated yearly for a non-union of the forearm declined during that period for two reasons. Firstly, our department was, and still is, a tertiary referral centre for failed fixation and/or non-unions starting in the 1970s and 1980s. Secondly, the technique of fixation became better known and union rates after primary surgery for forearm fractures improved. Additional cases between 2002 and 2008 were entered into the study cohort at admission for treatment by the senior author (P.K.). A non-union was defined as absence of healing after 4 months, or evident failure of treatment prior to that [22]. All patients with skeletal immaturity, congenital forms of non-union, or a follow-up of <12 months were excluded. As a result, 47 patients were included in the study cohort, which consisted of 35 men and 12 women with an average age of 37 years (range 16–76 years). The indications for treatment of the non-union were pain, limited function, forearm deformity and/or hardware failure.

Twenty-one fractures involved the left arm, 25 fractures involved the right arm and 1 patient fractured both arms. The mechanism of injury was a motorised vehicle accident in 26 patients, a fall in 12, and a crush injury in 9. The pattern of injury was a fracture of the diaphyseal radius and ulna in 18 patients, an isolated fracture of the diaphyseal ulna in 15, an isolated fracture of the diaphyseal radius in 7, a Monteggia fracture in 5, and a Galeazzi fracture-dislocation of the forearm in 2 patients. According to the AO classification of ulnar and radial shaft fractures [23], there were 6 type-A1, 1 type-A2, 7 type-A3, 13 type-B1, 4 type-B2, 11 type-B3, 3 type-C1, and 2 type-C2 fractures. Eighteen fractures (38%) were open; according to the system of Gustilo and Anderson [24, 25], there were six type-1, four type-2, and seven type-3A fractures. For one open fracture the Gustilo and Anderson type could not be determined. Eleven patients were polytraumatic with at least one more fracture in other areas. Ten patients had an associated nerve injury, two ulnar nerve lesions, five radial nerve lesions, a median nerve lesion, a combined radial and median nerve lesion and a brachial plexus lesion. One patient had a radial artery lesion, which was acutely repaired. The percentage of smokers was 58%. Prior treatment consisted of cast immobilisation in eight cases. Thirty-three patients received 1 previous operative treatment, which consisted of plate fixation in 22 (1 with primary grafting), external fixation in 3, and K-wires/Rush pins in 3. Five patients were converted early from a cast to plate fixation after an average of 9 days (range 4–20 days). In one patient external fixation was early switched to plate fixation and in one patient plate fixation was early switched to external fixation. Two patients underwent plate fixation twice, and one patient received an intramedullary nail twice after undergoing plate fixation twice. In one patient previous treatment was unknown. There were 51 non-unions in 47 patients, including a non-union of the radius in 16 patients, the ulna in 27 patients and of both ulna and radius in 4 patients. Four of the 18 patients that had initially broken both forearm bones produced non-unions of both radius and ulna, seven produced a non-union of the radius, and seven produced a non-union of the ulna. Four of the non-unions were classified as atrophic (8%), 13 as hypertrophic (25%) and 34 as oligotrophic (67%) [26].

The time between the injury and the index surgery that resulted in healing averaged 16 months (range 2–312 months). Sixteen surgeons were involved. Principles of surgery were consistently a thorough debridement of avital tissues, removal of failed hardware, restoration of alignment, length, rotation, stable fixation using compression if possible (tensioner device and/or lag screws), optimisation of a bone forming environment (including bone grafting if needed) allowing for early motion. Index surgery for non-union consisted of open reduction and plate fixation in combination with a graft in 30 cases (59%), open reduction and plate fixation alone in 14 cases (27%), and only a graft in 7 cases (14%). Grafting was performed in 32 cases with autogenous cancellous graft. Donor sites were the iliac crest in 24, olecranon in 7 and distal radius in 1. In four cases a tricortical iliac crest block was used and in one case a vascularised fibula graft was used. No use has been made of bone graft substitutes.

Follow-up data were obtained by retrospective review of medical records and selective invitations for a free clinical and radiographic examination when insufficient data were available. The retrospective character of the study withheld us from recording functional scores such as the DASH. The final functional result was therefore assessed in accordance to the system used by Anderson and colleagues [1] at the most recent visit at the orthopaedic outpatient service at our institution. This scoring system, which was recently used by Ring et al. [22] in a comparable study, rates an united fracture with <10° loss of elbow or wrist motion and <25% loss of forearm rotation as excellent, a healed fracture with <20° loss of elbow or wrist motion and <50% loss of forearm rotation as satisfactory, a healed fracture with more than 30° loss of elbow or wrist motion and more than 50% loss of forearm rotation as unsatisfactory, and a malunion, non-union, or unresolved chronic osteomyelitis as failure.

Results

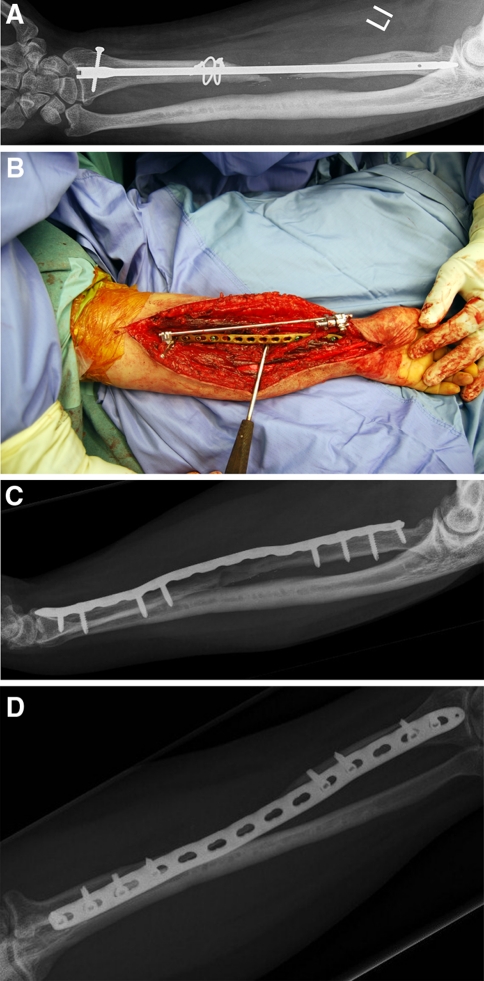

The average follow-up time was 75 months (range 12–315 months). All non-unions healed within 18 months after the index procedure (Figs. 1, 2) with a median time to union of 7 months (range 10–84 weeks). Range of motion at the most recent follow-up averaged 64° (range 10°–90°) for wrist flexion, 68° (range 15°–90°) for wrist extension, 64° (range 0°–80°) for pronation, 60° (range 0°–80°) for supination, 139° (range 120°–140°) for elbow flexion, and 2° (range 0°–50°) for elbow flexion contracture. Details on fracture type, treatment and function are summarised in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

a Anterior–posterior radiograph of an atrophic radius non-union in a 38-year-old female. She had undergone multiple previous attempts to obtain union at an outside hospital. Notice the protruding pin proximally. b Wide intra-operative exposure (Henry approach), with a 3.5-mm LCP plate on the radius. Intra-operative distraction maintaining radial length was obtained with a temporary external fixator. c, d Treatment consisted of autologous corticocancellous bone grafting and 3.5-mm LCP plate fixation. Radiographs at 15 months follow-up show a healed radius

Fig. 2.

Lateral radiograph showing a successfully treated hypertrophic ulnar non-union in a 38-year-old male. Fixation was obtained by means of a long compression plate-and-(lag)screw. Although this radiograph clearly shows an ulna minus that might have been exacerbated by using compression (shortening the ulna even more), the patient’s wrist and forearm function is normal and he is pain-free at 22 months follow-up

Table 1.

Demographics, treatment and outcome of the patient population

| Age/sex | Fracture type (AO) | Open (G&A) | Non-union location | Non-union type | Time from injury to index surgery (months) | Graft | F.U. (months) | Elbow flex/ext | Forearm pro/sup | Wrist flex/ext | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36M | A1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 5 | 31 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 45M | A1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 10 | 15 | 140/0 | 40/40 | 70/80 | Satisfactory | ||

| 16F | A1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 312 | Olecranon | 146 | 120/−15 | 30/80 | 70/80 | Satisfactory | |

| 66F | A1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 9 | 13 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 28M | A1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 3 | 12 | 130/0 | 40/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 38M | A1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 6 | 94 | 130/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 35M | A2 | Radius | Hypertrophic | 5 | 72 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 28M | A3 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 16 | 22 | 140/0 | 40/60 | 40/65 | Unsatisfactory | ||

| 50M | A3 | Grade 1 | Radius1 | Oligotrophic | 2 | 13 | 140/0 | 70/70 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 28M | A3 | Grade 1 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 6 | ICBG | 248 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent |

| 38F | A3 | Radius | Atrophic | 26 | ICBG | 15 | 140/0 | 40/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 45M | A3 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 34 | ICBG | 55 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 34F | A3 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 45 | ICBG | 84 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 20M | A3 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 20 | ICBG | 34 | 140/−10 | 70/60 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 50M | A3 | Grade 1 | Ulna1 | Oligotrophic | 2 | 13 | 140/0 | 70/70 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 70M | B1 (Galeazzi) | Radius | Oligotrophic | 12 | ICBG | 12 | 140/0 | 80/80 | Near full | Excellent | |

| 50M | B1 (Monteggia) | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 7 | ICBG | 70 | 140/0 | 60/60 | 60/50 | Unsatisfactory | |

| 41F | B1 | Ulna | Hypertrophic | 4 | 13 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 61M | B1 (Monteggia) | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 13 | ICBG | 32 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 42M | B1 (Monteggia) | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 5 | Olecranon | 12 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 39F | B1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 3 | 91 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 33F | B1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 30 | ICBG block | 21 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 18M | B1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 6 | ICBG | 295 | 140/0 | 70/30 | N/A | Satisfactory | |

| 36M | B1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 2 | 55 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | ||

| 40M | B1 (Monteggia) | Grade 1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 5 | ICBG | 156 | 140/0 | 80/50 | 70/80 | Excellent |

| 35M | B1 | Grade 1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 7 | 13 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 19M | B1 (Monteggia) | Grade 3A | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 12 | ICBG | 63 | Limited | Limited | Limited | Unsatisfactory |

| 28M | B1 | Open, grade N/A | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 5 | ICBG | 177 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent |

| 63M | B2 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 3 | ICBG block | 52 | 140/0 | 45/0 | 45/15 | Unsatisfactory | |

| 46M | B2 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 7 | ICBG block | 315 | 140/0 | 80/30 | 70/80 | Satisfactory | |

| 24M | B2 (Galeazzi) | Grade 2 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 4 | ICBG block | 25 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent |

| 28M | B2 | Grade 3A | Radius | Oligotrophic | 5 | ICBG | 40 | N/A | 45/0 | Poor | Unsatisfactory |

| 21F | B3 | Radius | Hypertrophic | 7 | Olecranon | 93 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 16M | B3 | Grade 3A | Radius2 | Hypertrophic | 5 | ICBG | 108 | 140/−5 | 45/0 | 15/10 | Unsatisfactory |

| 20F | B3 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 68 | ICBG | 174 | 140/0 | 80/50 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 37M | B3 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 6 | ICBG | 310 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 76F | B3 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 3 | Radius | 26 | 140/0 | 40/70 | 40/40 | Unsatisfactory | |

| 23M | B3 | Grade 3A | Radius3 | Oligotrophic | 3 | ICBG | 84 | 140/0 | 65/70 | 75/50 | Satisfactory |

| 38M | B3 | Grade 2 | Radius4 | Atrophic | 5 | ICBG | 113 | 130/0 | 20/45 | N/A | Unsatisfactory |

| 16M | B3 | Grade 3A | Ulna2 | Hypertrophic | 5 | ICBG | 108 | 140/−5 | 45/0 | 15/10 | Unsatisfactory |

| 30M | B3 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 14 | Olecranon | 24 | 140/0 | 50/60 | N/A | Excellent | |

| 49F | B3 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 4 | Olecranon | 20 | 140/0 | 80/40 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 22M | B3 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 10 | Olecranon | 98 | 140/0 | 80/80 | 70/80 | Excellent | |

| 50M | B3 | Grade 2 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 12 | ICBG | 13 | 140/0 | 40/40 | 70/80 | Satisfactory |

| 23M | B3 | Grade 3A | Ulna3 | Oligotrophic | 3 | ICBG | 84 | 140/0 | 65/70 | 75/50 | Satisfactory |

| 38M | B3 | Grade 2 | Ulna4 | Atrophic | 5 | ICBG | 25 | 130/0 | 45/0 | 15/30 | Unsatisfactory |

| 53M | C1 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 3 | ICBG | 24 | 140/0 | 70/45 | 90/75 | Satisfactory | |

| 21M | C1 | Ulna | Oligotrophic | 6 | Vascularized fibula | 114 | 140/0 | 0/80 | 70/90 | Satisfactory | |

| 47M | C1 | Ulna | Atrophic | 27 | ICBG | 30 | 120/−50 | 25/25 | 70/80 | Unsatisfactory | |

| 65F | C2 | Grade 1 | Radius | Oligotrophic | 7 | Olecranon | 30 | 140/0 | 80/60 | 70/80 | Excellent |

| 31M | C2 | Grade 3A | Radius | Oligotrophic | 6 | 32 | 140/0 | 45/40 | 80/15 | Unsatisfactory |

AO Müller AO classification of fractures, G&A Gustillo and Anderson classification of open wound fractures, F.U. follow-up time, 1234 both bone non-union, ICBG iliac crest bone graft

According to the system of Anderson and colleagues 29 patients (62%) had an excellent result, 8 (17%) a satisfactory result, and 10 (21%) had an unsatisfactory result. No treatments resulted in failure. The reasons for the unsatisfactory results were limited range of motion of the wrist in eight patients, elbow stiffness in one and a median nerve lesion in one. Concerning the 18 patients that had an open fracture at the time of injury, 8 patients had an excellent result (44%), 3 patients had a satisfactory result (17%), and 7 patients had an unsatisfactory result (39%).

Complications and additional surgery

Twenty-seven patients had hardware removal after consolidation. This used to be fairly standard at our institution but it is not any more. One patient refractured his radius after hardware removal and underwent renewed plate fixation. One patient underwent manipulation under anaesthesia for wrist stiffness and one had a forearm tenolysis. Two patients had a postoperative nerve injury, of which one developed enduring meralgia paraesthetica after iliac crest bone harvesting, and one had a radial nerve palsy, which ultimately recovered over time. In two cases an infection developed at the graft donor site, one at the iliac crest site and the other at the fibula. In both cases the infections were successfully eradicated with debridement and antibiotics.

Discussion

The standard technique of compression plate-and-screw fixation in acute diaphyseal forearm fractures is well established [27]. Their union rate has been consistently high (above 95% healing) with good functional outcomes in up to 85% [1, 2, 4, 5, 9]. Risk factors for development of a non-union are comminution, high energy fractures, open fractures and suboptimal surgical technique. Adherence to a “biologic surgical technique” with preservation of soft tissue attachments is important. There is no role for minimally invasive techniques as limited exposure will likely compromise the ability to obtain anatomic alignment. Stability of fixation is important in achieving early consolidation [5].

Reporting a union rate of 100%, our series shows that treatment of diaphyseal forearm non-unions is straightforward with a high success rate if “classic” principles of non-union surgery are followed. These principles are a thorough debridement of avital tissues, removal of failed hardware, restoration of alignment, length, rotation, stable fixation using compression if possible (tensioner device and/or lag screws), optimisation of a bone forming environment (including bone grafting if needed) allowing for early motion. However, despite clinical and radiological consolidation, a significant number of patients (21% in our series) might have an unsatisfactory long-term functional outcome due to limited range of motion. When limited to open fractures 39% had an unsatisfactory result.

Our results show that oligotrophic non-unions are more common than atrophic- or hypertrophic non-unions. In contrast to another report, we did not find a higher risk for the ulna than for the radius to produce a non-union in both bone fractures [28].

To the best of our knowledge, our cohort presents the largest series of forearm non-unions with a minimum of 12 months follow-up and both functional and radiological outcome in the English literature.

The involvement of 16 surgeons might suggest a wide variety of surgical detail. However, we argue that the high success rate shown in this report suggests that our described technique of treating forearm non-unions is one that is reproducible and can be circulated among surgeons.

As many patients in our patient group were referred to us from outside hospitals, data from the original injury (e.g. soft tissue condition) and surgery were often incomplete. This precluded us to define the exact cause of failure, although we can infer this is likely to be a combination of factors including biology, biomechanics, surgical technique and co-morbidities. It is suggested in the literature that intramedullary wires, K-wires, simple lag screws or one-third tubular plates carry a high risk of providing inadequate fixation [9].

Current fixation of choice is a relatively long 3.5-mm compression plate. Most authors advise six cortices on each side of the fracture; more recently use of only four cortices on each side was suggested [12]. The choice of bone graft has historically been a topic of debate. Nicoll [29] was one of the first to report on the use of (cortico)-cancellous autograft in forearm non-unions. Numerous authors have reported on its (modified) use, as was noted in a review by Faldini and colleagues [19]. Ring and colleagues indeed showed that for atrophic non-unions with segmental defects up to 6 cm non-vascularised autogenous corticocancellous grafts leads to bony union [22]. Recently, Baldy Dos Reis and colleagues [30] showed that treatment with corticocancellous bone grafts and plate fixation for both atrophic and hypertrophic non-unions led to excellent radiological and functional outcome in their cohort of 31 patients. Petalling of both sides (1.5–2 cm) of the non-union, with opening of the medullar canal to remove the sclerotic cap using a drill is a very important aspect of the procedure. We generally take the graft from the iliac crest, if done appropriately, deformity at the donor site is negligible with a low morbidity [31]. Given a compliant well-vascularised soft tissue envelope, vascularisation of corticocancellous graft often is rapid, with incorporation of the graft within a few weeks [22].

The use of non-vascularised bone blocks has been proposed by various authors [19, 26, 29, 32–34]. Of note is that in these studies patients were often protected postoperatively in a cast for a long period.

In review of the literature, it seems that non-unions of the ulnar and radial diaphyseal defects up to 6 cm can be treated with autologous cancellous bone grafts [22]. For defects between 6 and 10.5 cm there are some conflicting reports [32, 34]. Davey et al. [34] warned against the use of a non-vascular bone graft for defects larger than 6 cm. In case of a substantial bone defect in combination with a poor soft tissue environment, the use of an osteocutaneous free flap is a viable option [35–37]. The use of 3.5-mm (DC, LC-DCP, LCP) plates is preferred over 4.5-mm plates as these are too bulky for the forearm. There have been reports on the use of intramedullary nailing of non-unions of the forearm. We chose not to use this technique and would caution lack of compression and rotational control [38–40]. The most recent of these reports concluded that interlocking intramedullary nailing of non-unions of the diaphysis of ulna or radius should not be considered an alternative to plate fixation [38]. Their functional outcome indicated inferior results to plate-and-screw techniques.

In summary, classic AO technique with adequate debridement, eradication of infection and stable fixation using compression (using lag screws, eccentric drilling and/or AO tensioner device) will lead to successful healing of the vast majority of forearm non-unions. Longer plates (3.5 mm) with a high plate-span/screw ratio are preferred. In case of osseous defects up to 6 cm, autogenous corticocancellous bone grafts are recommended [22]. For larger defects free tissue transfer should be considered. Despite a very high chance of obtaining clinical and radiological healing of the non-union, patients should be informed that long-term functional outcome might be disappointing as was shown in this cohort in 21%.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Anderson LD, Sisk D, Tooms RE, Park WI., 3rd Compression-plate fixation in acute diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;3:7–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman MW, Gordon JE, Zissimos AG. Compression-plate fixation of acute fractures of the diaphyses of the radius and ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;2:159–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Droll KP, Perna P, Potter J, Harniman E, Schemitsch EH, McKee MD. Outcomes following plate fixation of fractures of both bones of the forearm in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;12:2619–2624. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hertel R, Pisan M, Lambert S, Ballmer FT. Plate osteosynthesis of diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna. Injury. 1996;8:545–548. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(96)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross ER, Gourevitch D, Hastings GW, Wynn-Jones CE, Ali S. Retrospective analysis of plate fixation of diaphyseal fractures of the forearm bones. Injury. 1989;4:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(89)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern PJ, Drury WJ. Complications of plate fixation of forearm fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;175:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei SY, Born CT, Abene A, Ong A, Hayda R, DeLong WG., Jr Diaphyseal forearm fractures treated with and without bone graft. J Trauma. 1999;6:1045–1048. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199906000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright RR, Schmeling GJ, Schwab JP. The necessity of acute bone grafting in diaphyseal forearm fractures: a retrospective review. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;4:288–294. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikek M, Vidmar G, Tonin M, Pavlovcic V. Fracture-related and implant-specific factors influencing treatment results of comminuted diaphyseal forearm fractures without bone grafting. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;6:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0668-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ring D, Rhim R, Carpenter C, Jupiter JB. Comminuted diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna: does bone grafting affect nonunion rate? J Trauma. 2005;2:438–441. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174839.23348.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung F, Chow SP. A prospective, randomized trial comparing the limited contact dynamic compression plate with the point contact fixator for forearm fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;12:2343–2348. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders R, Haidukewych GJ, Milne T, Dennis J, Latta LL. Minimal versus maximal plate fixation techniques of the ulna: the biomechanical effect of number of screws and plate length. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;3:166–171. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deluca PA, Lindsey RW, Ruwe PA. Refracture of bones of the forearm after the removal of compression plates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;9:1372–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidaka S, Gustilo RB. Refracture of bones of the forearm after plate removal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;8:1241–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labosky DA, Cermak MB, Waggy CA. Forearm fracture plates: to remove or not to remove. J Hand Surg (Am) 1990;2:294–301. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(90)90112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosson JW, Shearer JR. Refracture after the removal of plates from the forearm. An avoidable complication. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;3:415–417. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodge HS, Cady GW. Treatment of fractures of the radius and ulna with compression plates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;6:1167–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langkamer VG, Ackroyd CE. Internal fixation of forearm fractures in the 1980s: lessons to be learnt. Injury. 1991;2:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(91)90063-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faldini C, Pagkrati S, Nanni M, Menachem S, Giannini S. Aseptic forearm nonunions treated by plate and opposite fibular autograft strut. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(8):2125–2134. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0827-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadden WA, Reschauer R, Seggl W. Results of AO plate fixation of forearm shaft fractures in adults. Injury. 1983;1:44–52. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(83)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard MJ, Ruch DS, Aldridge JM., 3rd Malunions and nonunions of the forearm. Hand Clin. 2007;2:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ring D, Allende C, Jafarnia K, Allende BT, Jupiter JB. Ununited diaphyseal forearm fractures with segmental defects: plate fixation and autogenous cancellous bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;11:2440–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller M, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schatzker J. The comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones. Berlin: Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;4:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma. 1984;8:742–746. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber BG, Čech O. Pseudarthrosis: pathophysiology, biomechanics, therapy, results. Philadelphia: Grune & Stratton; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller ME, Allgower M, Schneider R, Willeneger H. Manual of internal fixation. Techniques recommended by the AO-ASIF Group. Berlin: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai RB. Analysis of 81 cases of nonunion of forearm fracture. Chin Med J (Engl) 1983;1:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicoll EA. The treatment of gaps in long bones by cancellous insert grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1956;1:70–82. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.38B1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldy Dos Reis F, Faloppa F, Alvachian Fernandes HJ, Manna Albertoni W, Stahel PF. Outcome of diaphyseal forearm fracture-nonunions treated by autologous bone grafting and compression plating. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2009;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Younger EM, Chapman MW. Morbidity at bone graft donor sites. J Orthop Trauma. 1989;3:192–195. doi: 10.1097/00005131-198909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moroni A, Rollo G, Guzzardella M, Zinghi G. Surgical treatment of isolated forearm non-union with segmental bone loss. Injury. 1997;8:497–504. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(97)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbieri CH, Mazzer N, Aranda CA, Pinto MM. Use of a bone block graft from the iliac crest with rigid fixation to correct diaphyseal defects of the radius and ulna. J Hand Surg (Br) 1997;3:395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(97)80411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davey PA, Simonis RB. Modification of the Nicoll bone-grafting technique for nonunion of the radius and/or ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;1:30–33. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B1.11799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dell PC, Sheppard JE. Vascularized bone grafts in the treatment of infected forearm nonunions. J Hand Surg (Am) 1984;5:653–658. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safoury Y. Free vascularized fibula for the treatment of traumatic bone defects and nonunion of the forearm bones. J Hand Surg (Br) 2005;1:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jupiter JB, Gerhard HJ, Guerrero J, Nunley JA, Levin LS. Treatment of segmental defects of the radius with use of the vascularized osteoseptocutaneous fibular autogenous graft. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;4:542–550. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong G, Cong-Feng L, Hui-Peng S, Cun-Yi F, Bing-Fang Z. Treatment of diaphyseal forearm nonunions with interlocking intramedullary nails. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450:186–192. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000214444.87645.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen NO. Kuntscher intramedullary reaming and nail fixation for nonunion of the forearm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;116:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann A, Hessmann MH, Rudig L, Kuchle R, Rommens PM. Intramedullary osteosynthesis of the ulna in revision surgery. Unfallchirurg. 2004;7:583–592. doi: 10.1007/s00113-004-0790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]