Abstract

The histological differential diagnosis between melanotic schwannoma, primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions and cellular blue nevus can be challenging. Correct diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma is important to select patients who need clinical evaluation for possible association with Carney complex. Recently, we described the presence of activating codon 209 mutations in the GNAQ gene in primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions. Identical codon 209 mutations have been described in blue nevi. The aims of the present study were to (1) perform a histological review of a series of lesions (initially) diagnosed as melanotic schwannoma and analyze them for GNAQ mutations, and (2) test the diagnostic value of GNAQ mutational analysis in the differential diagnosis with leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions. We retrieved 25 cases that were initially diagnosed as melanotic schwannoma. All cases were reviewed using established criteria and analyzed for GNAQ codon 209 mutations. After review, nine cases were classified as melanotic schwannoma. GNAQ mutations were absent in these nine cases. The remaining cases were reclassified as conventional schwannoma (n = 9), melanocytoma (n = 4), blue nevus (n = 1) and lesions that could not be classified with certainty as melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma (n = 2). GNAQ codon 209 mutations were present in 3/4 melanocytomas and the blue nevus. Including results from our previous study in leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions, GNAQ mutations were highly specific (100%) for leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions compared to melanotic schwannoma (sensitivity 43%). We conclude that a detailed analysis of morphology combined with GNAQ mutational analysis can aid in the differential diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma with leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions.

Keywords: Melanotic schwannoma, Peripheral nerve sheath tumor, GNAQ, Carney complex, Melanocytoma, Blue nevus

Introduction

Melanotic schwannoma is a rare variant of schwannoma composed of cells having the ultrastructure and immunophenotype of Schwann cells but containing melanosomes in varying stages of maturation [24, 25]. They show a peak incidence in the fourth decade, and affect males and females equally. About half of these tumors arise in close proximity to the neural axis. These neoplasms are often associated with spinal nerve roots, cranial nerves or arising from the paraspinal sympathetic chain [5, 15]. The other half arises in a wide variety of sites including the gastrointestinal tract, soft tissues, skin, heart and liver [3, 8, 10, 13, 25]. The biological behavior of melanotic schwannomas can be unpredictable with metastasis reported in up to 10% of cases, sometimes even in the absence of histological features suggestive of aggressive behavior [5, 27]. A specific subgroup of melanotic schwannomas contains psammoma calcifications. About half of these so-called psammomatous melanotic schwannomas occur in the setting of the autosomal dominant Carney complex, a multiple neoplasia syndrome characterized by a markedly increased risk to develop myxomas, mucocutaneous lentigines and blue nevi, endocrine hyperactivity and/or psammomatous melanotic schwannomas [5]. Isolated cases of non-psammomatous melanotic schwannomas have been associated with Carney complex as well [6]. Nearly two-thirds of patients with Carney complex have mutations spread over the PRKAR1A gene, which encodes the R1α regulatory subunit of cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase A [14, 29].

The differential diagnosis between melanotic schwannomas and pigmented melanocytic lesions can be difficult, especially in small biopsy specimens. It includes primary or metastatic melanoma, a diagnosis with obvious prognostic and therapeutic relevance. In addition, melanotic schwannomas may histologically closely resemble leptomeningeal melanocytomas and cellular blue nevi [20]. Immunohistochemical stains are not always useful in sorting out this differential diagnosis. All these lesions generally express S-100 (which can be explained by their common neural crest origin) and one or more melanocytic markers. Although stains for components of the basement membrane can be useful in discriminating tumors with schwannian differentiation from tumors with melanocytic differentiation, overlap in staining patterns has been noted and can impair interpretation, especially in small biopsy specimens [4, 12, 21, 26].

Recently, we reported the presence of activating mutations in the GNAQ gene at codon 209 in primary leptomeningeal melanocytomas (50%) and melanomas (25%) [16]. The GNAQ gene maps on chromosome 9q21, and encodes the α-subunit of a heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein that couples G-protein-coupled receptor signaling to the MAP kinase pathway [22]. GNAQ codon 209 mutations form an alternative route to MAP kinase activation [28]. Identical oncogenic mutations in the GNAQ gene have been reported in blue nevi (83%) and uveal melanoma (46%) [17, 28].

The aims of the present study were (1) to perform a thorough histological review of a series of lesions that were (initially) diagnosed as melanotic schwannoma and to analyze these cases for mutations in the GNAQ gene, and (2) to assess the diagnostic value of GNAQ mutational analysis in the differential diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma with primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions by including data from our previous study on GNAQ mutations in leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions [16].

Materials and methods

Patients and histopathology

For this retrospective study, formalin fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissues of melanotic schwannomas were retrieved from archives of various Departments of Pathology in The Netherlands. The cases were obtained through the Dutch nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive (PALGA) [7]. All cases (n = 25) were initially diagnosed as melanotic schwannomas.

Formalin fixed and paraffin embedded tissues were sectioned at 4 μm, deparaffinized, and subjected to antigen retrieval by limited protein digestion or citrate (CC1) and microwave treatment. Slides were then incubated at room temperature with antibodies to S-100 protein (polyclonal, 1:800, Dako Co., Lot 00060051), Melan-A (Mart-1, 1:800, Neomarkers, Lot 799P807C), HMB-45 (1:50, Neomarkers, Lot 23068), MIB-1 (Ki-67, 1:200, Dako Co., Lot 00045312), EMA (E-29, 1:50, Dako Co., Lot 00051982), Collagen type IV (monoclonal, 1:1,250, Sigma, Lot 062K4819) and Laminin (polyclonal, 1:100, Thermo, Lot 82H907B). Amino-ethylcarbazole served as chromogen. Reticulin stains (Laguesse) were performed on each case. Schmorl and Perl’s (iron) stains were performed to confirm melanin pigmentation.

Histology was revised independently by two pathologists (HK, BK) without knowledge of molecular results. Revision of the slides included scoring of histological criteria and immunohistochemical stains.

The deposition of basement membrane material in the reticulin, Collagen type IV and Laminin stains was categorized into three staining patterns. The pericellular pattern was represented by an extensive network of basement membrane material around individual tumor cells, consistent with schwannian differentiation [12, 24]. The nested/perilobular pattern consisted of deposition of basement membrane material around nests of tumor cells (rather than around individual tumor cells), and is typically seen in melanocytic lesions [26]. The biphasic staining pattern was characterized by areas with nested staining as well as areas with pericellular staining, and has been described in melanotic schwannomas [12, 24].

After revision, the cases were reclassified as (1) melanotic schwannoma, with or without psammoma bodies and/or fat, (2) conventional schwannoma, (3) melanocytoma, (4) lesion not further classified with certainty as melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma, or (5) blue nevus. Criteria used for classification are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Morphological, esp. histopathological criteria used for classification

| Conventional schwannomaa | Melanotic schwannomaa,b | Leptomeningeal melanocytoma (MC)c | Cellular blue nevusb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localization | Majority outside central nervous system, most often skin and subcutaneous tissue | Near the neural axis (esp. spinal nerve roots, cranial nerves) or peripherally located in a wide variety of sites (soft tissue, skin, etc.) | Mostly at the cervical and thoracic spinal level, sometimes posterior fossa and supratentorial compartment | Skin (mainly dermis); frequently buttocks or sacrococcygeal region |

| Origin | Nerve sheath (schwann cell) | Nerve sheath (schwann cell) | Leptomeningeal melanocyte | Dermal melanocyte |

| Growth pattern, margin | Circumscribed, encapsulated | Circumscribed, often encapsulated | Circumscribed, non-encapsulated; MC with invasion of CNS is classified as intermediate-grade MC | Non-encapsulated; both infiltrative and pushing border |

| Melanin pigmentation | Absent | Variably, often heavily pigmented | Variably, often heavily pigmented; can rarely be absent | Variably; can rarely be absent |

| Psammoma bodies and/or fat | Absent | Present in the psammomatous form | Absent | Absent |

| Schwannian featuresd | Present | Often less pronounced than in conventional schwannoma | Absent | Degenerative changes reminiscent of ancient schwannoma can be present |

| Cell phenotype | Spindle | Spindle, epithelioid | Spindle, epithelioid | Spindle, ovoid, dendritic (biphasic architecture) |

| Nuclear atypia | Generally absent; ancient changes (‘degenerative atypia’) can be present | Usually mild; prominent nuclear atypia with increased mitotic activity and necrosis is indicative of aggressive behavior | Generally absent; MC with increased mitotic activity (2–5 per 10 HPF) is classified as intermediate-grade MC | Variable; absence of necrosis, mitotic activity < 2 per 2 mm2 |

| S-100 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| HMB-45 and/or Melan-A | Negative | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Basement membrane staining | Pericellular pattern | Pericellular or biphasic (pericellular and nested) pattern | Nested pattern | Predominantly nested pattern |

The diagnosis of ‘melanotic schwannoma’ and ‘conventional schwannoma’ was based on WHO criteria [24]. Additional detailed histological criteria of melanotic schwannoma were retrieved from Mooi [20], and included circumscribed, often encapsulated tumors consisting of spindle to epithelioid cells, with or without psammoma bodies and/or fat, variable melanin pigmentation, S-100 positivity and expression of Melan-A and/or HMB-45. Schwannomas lacking positivity for both HMB-45 and Melan-A were classified as conventional schwannomas. A pericellular staining pattern in the basement membrane stains served as an additional criterion for conventional schwannoma, while in melanotic schwannomas also a biphasic staining pattern can be present [12, 24].

The diagnosis of ‘melanocytoma’ was based on histological criteria as described by Brat et al. [1, 2]. This included circumscribed, non-encapsulated lesions consisting of nests or fascicles of spindle and/or epithelioid cells with little nuclear atypia and variable melanin pigmentation. Immunohistochemical criteria included S-100 positivity, expression of Melan-A and/or HMB-45, and a nested staining pattern in the basement membrane stains. Lesions with increased mitotic activity or invasion of neuroglial tissue were classified as ‘intermediate-grade’ melanocytomas.

The diagnosis of ‘cellular blue nevus’ was based on histological criteria described by Mooi [19]. This included a primary location of the lesion within the dermis with a biphasic architecture, especially at the base of the lesion, consisting of nodules and sheets of pale, oval melanocytes intermingled with pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely arranged in sclerotic stroma. For statistical evaluation, 19 leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions from our previous study were included [16].

DNA extraction

About five manually dissected sections of 10 μm FFPE tissue with an estimated tumor cell percentage of at least 60% were used for DNA extraction. After heating in ATL buffer, the tissue sections were incubated in proteinase K for 1 hour, followed by subsequent purification of the DNA according to the manufacturer (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, QIAGEN GmbH, Germany). DNA sample concentration was assessed spectrophotometrically (Varian Cary 50 spectrophotometer, Agilent Technologies).

Mutational analysis

Direct sequence analysis of GNAQ exon 5 was performed on DNA specimens from 25 pigmented lesions of schwannian or melanocytic origin. PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 25 μl, containing 50 ng DNA, PCR-buffer IV (Integro), 37 mM MgCl2, 250 μM of dNTPs, 37.5 μg bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 10 pmol of forward primer (p740, sequence: 5′ TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTTCCCTAAGTTTGTAAGTAGTGC 3′) and reverse primer (p705, sequence: 5′ CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCCTTACCTCATTGTCTGAC 3′, or p695, sequence: 5′ TCCATTTTCTTCTCTCTGACC 3′) and 0.05 units of thermostable DNA polymerase (Sigma). Primers p740 and p705 contained a M13 forward and a M13 reverse consensus sequence, respectively, enabling standardized sequencing of different exons.

DNA amplification was performed in duplicate in a PTC 200 Thermal Cycler (MJ Research). The PCR was started with 5 min at 92°C and followed with 35 cycles of denaturation 45 s at 94°C, annealing at 62°C for 45 s and extension at 72°C for 45 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 20 min and cooling down for 5 min at 20°C. PCR products were purified with MinElute plates (Qiagen). After analyzing the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%; Invitrogen), 1–4 μl of the PCR products was sent in for sequence analysis using an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Because the DNA quality of some specimens was suboptimal, different primer combinations were used in the PCR. The DNA samples of cases 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 13, 14, 22 and 23 were of sufficient quality and the primer combination p740 and p705, yielding a PCR product of 224 base pairs (bp), was used for DNA amplification. Sequence analysis was performed using the M13 forward primer and reverse primer on duplicate DNA amplifications of the same specimen. For the DNA samples that were strongly degraded (cases 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25), the primer combination p740 and p695, yielding a PCR product of 134 bp, was used. Sequence analysis (in duplicate) of these samples was performed using the forward primer only, since the reverse primer p695 is closely flanking the mutation hotspot. By sequence analysis of the entire PCR products, it was shown that the primers used specifically amplified the GNAQ gene (accession nr: NM_002072.2) and not its pseudogene (GNAQP1; accession nr: NG_000862.4v). The amplified gene sequence was specific for the GNAQ gene, and nucleotides that are present in the pseudogene were not detected [9].

Statistical analysis

The diagnostic value of GNAQ mutational analysis in the differential diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma with primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions was tested using additional data from our previous study on GNAQ mutations in primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions [16]. Sensitivity and specificity of GNAQ mutational analysis were calculated. To assess whether the difference in GNAQ mutational status between melanotic schwannoma and leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions was statistically significant, we performed Fisher’s exact test (SPSS 16.0 for Windows).

Results

Patient and histopathological characteristics

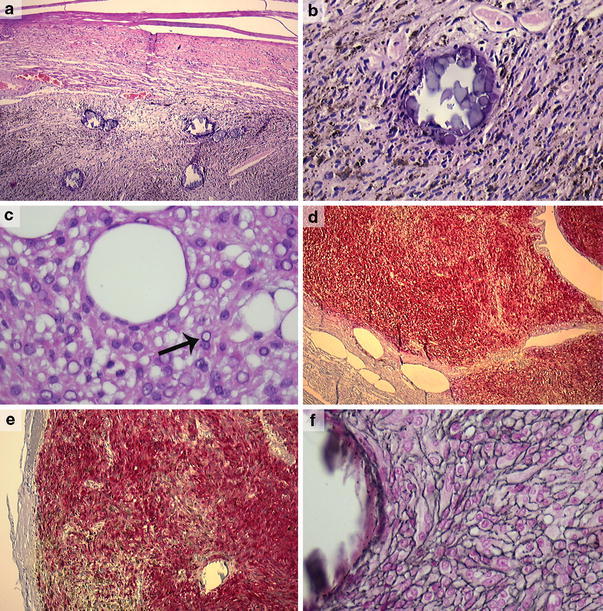

We retrieved 25 lesions initially diagnosed as melanotic schwannomas from the archives of various Departments of Pathology in The Netherlands. After revision, the lesions were reclassified using the above-mentioned criteria into nine melanotic schwannomas, nine conventional schwannomas, four melanocytomas, one blue nevus and finally two lesions that could not be further classified with certainty as melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma. Patient and histopathological characteristics are summarized in Table 2. As far as data were available, the melanotic schwannomas had an equal sex distribution and the mean age was 37.2 years. Most melanotic schwannomas were located around the spinal cord (7/9), while two lesions were located in the extremities (lower arm and lower leg). As far as could be evaluated on the slides, melanotic schwannomas were circumscribed, encapsulated tumors (6/9) (Fig. 1a) with variably but mostly intense melanin pigmentation (6/9) (Fig. 1b). Eight of nine melanotic schwannomas contained psammoma bodies (Fig. 1a, b) and, in addition, one melanotic schwannoma contained large, empty vacuoles resembling fat (Fig. 1c). Tumor cells were arranged in sheets and fascicles and varied from spindle to epithelioid, often with nuclear pseudoinclusions (Fig. 1c) and conspicuous nucleoli. In some cases, there was nuclear palisading and one case showed Antoni A and B areas together with Verocay bodies (case 4). Marked nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis, and invasion in surrounding structures were absent. These tumors were all negative in the EMA stains (excluding meningioma). MIB-1 staining was less than 1%. S-100 stains showed a diffuse and strong expression in all melanotic schwannomas (Fig. 1d). In addition, all lesions showed positivity for Melan-A and HMB-45 (Fig. 1e). Reticulin, Collagen type IV and Laminin stains showed in four of nine cases an extensive network of basement membrane material around individual tumor cells (pericellular pattern), consistent with schwannian differentiation (Fig. 1f). In five melanotic schwannomas, a biphasic staining pattern was present consisting of areas with pericellular deposition of basement membrane material next to areas with deposition around nests of tumor cells (nested/perilobular pattern). One lesion initially diagnosed elsewhere as a ‘peripherally located melanotic schwannoma’ was reclassified as a cellular blue nevus (case 19) [19].

Table 2.

Patient and histopathological characteristics and results of mutational analysis

| Patient | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Localization | Origin from nerve/ganglion | Circumscribed, capsule | Pigmentation | Psammoma bodies | Cell type | Schwannian features | Nuclear pleomorphism | S-100 | HMB-45 | Melan-A | Basement membrane staining | GNAQ exon 5 mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 75 | MS | L1–L2 | na | + | 1+ | + | S | Pa | mi | 2+ | 1+ | 1+ | B | – |

| 2 | F | 35 | MS | L1–5 | + | + | 3+ | + | E, S | Pa | mi | 2+ | 1+ | 2+ | B | – |

| 3 | M | 42 | MS | L2 | na | + | 3+ | − | S | – | mi | 2+ | 2+ | 1+ | B | – |

| 4 | na | na | MS | C2 | + | + | 3+ | + | E, S | A, V | mi | 2+ | 2+ | 1+ | P | – |

| 5 | na | na | MS | C1 | na | na | 3+ | + | S | – | mi | 2+ | 1+ | 2+ | P | – |

| 6 | na | na | MS | C4 | na | na | 3+ | + | E, S | – | mi | 2+ | 2+ | 2+ | B | – |

| 7 | M | 35 | MS | Lumbal | + | na | 3+ | + | S | Pa | mi | 2+ | 1+ | 2+ | B | – |

| 8 | F | 23 | MS | Lower arm | na | + | Focal 1+ | +, fat | E | – | mi | 2+ | 1+ | 1+ | P | – |

| 9 | M | 13 | MS | Lower leg | + | + | Focal 1+ | + | E, S | – | mi | 2+ | 1+ | 1+ | P | – |

| 10 | M | 72 | Sw | Vestibular nerve | na | na | 2+ | − | S | Pa | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 11 | F | 60 | Sw | Th11 | na | na | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa, V | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 12 | F | 32 | Sw | Retroperitoneum | na | + | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa, A | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 13 | M | 42 | Sw | sacrum | na | + | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 14 | na | na | Sw | Intercostal nerve | na | + | 1+ | − | S | Pa, A | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 15 | M | 49 | Sw | S1 | na | na | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa, A | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 16 | F | 74 | Sw | S2 | + | na | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 17 | F | 74 | Sw | Groin | na | na | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa, A | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 18 | M | 44 | Sw | Sacral | na | + | Focal 1+ | − | S | Pa, A | mi | 2+ | neg | neg | P | – |

| 19 | na | na | Blue nevus | Foot | na | + | 2+ | − | S, O | – | mi | Focal 1+ | 2+ | Focal 1+ | N | c626A>T, pGln209Leu |

| 20 | na | na | IMC | Cauda | na | No, invasion of CNS | 1+ | − | S | – | mi | Focal 1+ | 2+ | 2+ | N | c626A>T, pGln209Leu |

| 21 | na | na | IMC | IM | na | No, invasion of CNS | 3+ | − | E, S | – | mi | Focal 1+ | 2+ | 1+ | N | – |

| 22 | na | na | IMC | IM | na | No, invasion of CNS | 1+ | − | E | – | mi | Focal 1+ | 2+ | 1+ | N | c626A>T, pGln209Leu |

| 23 | na | na | MC | EM | na | na | 3+ | − | E | – | mi | Focal 1+ | 2+ | 1+ | N | c626A>T, pGln209Leu |

| 24 | F | 41 | NOS | L5 | + | na | 3+ | − | E, S | – |

mo sev |

1+ | 1+ | 2+ | B | − |

| 25 | na | na | NOS | CPA | na | na | 3+ | − | S | – | mi | Focal 1+ | 2+ | 1+ | N | c626A>T, pGln209Leu |

na data not available, MS melanotic schwannoma, Sw conventional schwannoma with limited pigment (neuromelanin, lipofuscin), IMC intermediate-grade melanocytoma, MC melanocytoma, NOS lesion not further classified with certainty as melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma, IM intramedullary, EM extramedullary, CPA cerebellopontine angle, S spindle cell phenotype, E epithelioid cell phenotype, O ovoid, Pa palisading of nuclei, V Verocay bodies, A Antoni A and B pattern, mi mild, mo moderate, sev severe, B biphasic, P pericellular, N nested

Fig. 1.

Melanotic schwannoma (case 4) showing a circumscribed tumor, covered by a fibrous capsule and containing several psammoma bodies (a) (×50). Detail of the same lesion showing spindle cell morphology, an ample amount of melanin pigment and a psammoma body (case 4) (b) (×200). Melanotic schwannoma (case 8) with more epithelioid cell morphology, nuclear pseudoinclusions (arrow) and large vacuoles resembling fat (c) (×400). Strong and diffuse positivity for, respectively, S-100 and HMB-45 in a melanotic schwannoma (case 4) (d, e) (×25, ×100). Same lesion with pericellular deposition of basement membrane material (case 4) (f) (Laguesse stain, ×400)

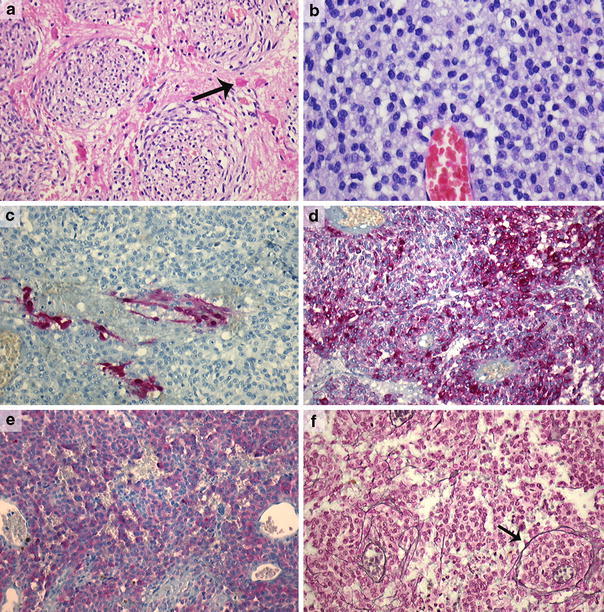

Nine lesions initially diagnosed elsewhere as melanotic schwannoma were reclassified as conventional schwannomas. These lesions showed the typical histological features of schwannomas with frequent Antoni A and B areas, nuclear palisading, blood vessel hyalinization and wavy nuclei. We did not classify them as melanotic schwannoma, because positivity for both Melan-A and HMB-45 was lacking. They all contained focally some fine intracytoplasmic grayish pigment in tumor cells (Schmorl positive). Furthermore, extensive areas with deposition of basement membrane material around individual tumor cells in the basement membrane stains were present. Based on the criteria described by Brat et al. [1, 2], four lesions located around the spinal cord were reclassified as melanocytomas. Three of them showed an infiltrative growth pattern in the neuroglial tissues and were classified as intermediate-grade melanocytomas (Fig. 2a). All lesions consisted of fascicles and nests of spindle and/or epithelioid cells with variable melanin pigment. Nuclei were round to oval and uniform in size, with mostly small nucleoli (Fig. 2b). Prominent nuclear atypia was absent. In contrast to the melanotic and conventional schwannomas, S-100 was only focally positive (Fig. 2c), while Melan-A and HMB-45 were more diffusely positive (Fig. 2d, e). MIB-1 staining was less than 1% in all cases. Reticulin, Collagen type IV and Laminin stains showed deposition of basement membrane material around vascular structures and nests of tumor cells (nested/perilobular), but not around individual tumor cells (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2.

Intermediate-grade melanocytoma (case 20) with invasion of neuroglial tissue; note the Rosenthal fibers (arrow) in the surrounding neuropil (a) (×200). Epithelioid cell morphology with bland nuclei and small nucleoli in a melanocytoma (case 22) (b) (×400). Focal positivity for S-100 in the same lesion (case 22) (c) (×200). Diffuse positivity for HMB-45 and Melan-A, respectively, in the same lesion (d, e) and a nested staining pattern in the reticulin stain (f) (case 22) (Laguesse stain, ×200)

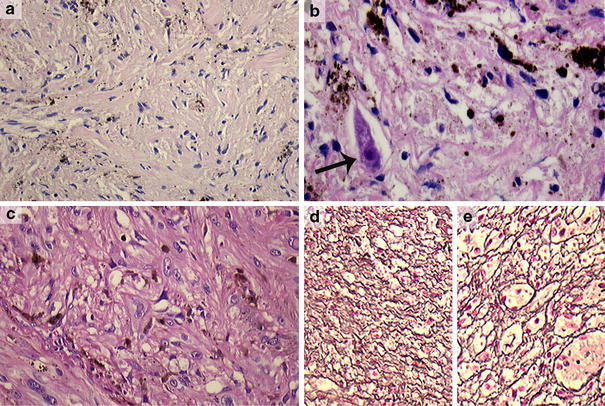

Finally, two lesions could not be classified with certainty into melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma (cases 24 and 25). Case 24 was a variably, partly heavily pigmented lesion consisting of spindle to pleiomorphic cells (Fig. 3a, c). The lesion showed infiltrative growth in or from a ganglion at the lumbar spinal region (Fig. 3b). The nuclei showed moderate to strong atypia with conspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 3c). MIB-1 staining was less than 10%. Psammoma bodies were absent. S-100, Melan-A and HMB-45 stains were diffusely positive. The reticulin, Collagen type IV and Laminin stains showed a biphasic pattern (Fig. 3d, e). Based on these histological features, we favored the diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma with atypical features suggestive of aggressive behavior. For case 25, only limited biopsy material was available which impaired unequivocal histological assessment. It concerned a heavily pigmented lesion located at the cerebellopontine angle consisting of spindle cells with mild cytonuclear atypia and small nucleoli. S-100 was focally positive, while the Melan-A and HMB-45 stains were diffusely positive. A nested/perilobulated staining pattern was present in the reticulin, Collagen type IV and Laminin stains. In this case, we favored the diagnosis of melanocytoma.

Fig. 3.

Case 24 was a variably, partly heavily pigmented lesion consisting of spindle to pleomorphic cells (a, c) (×200), showing infiltrative growth in a ganglion at the lumbar spinal region with dispersed incorporated ganglion cells (arrow) (b) (×400). The nuclei showed marked atypia with conspicuous nucleoli (c) (×200). In the reticulin stain, both a pericellular (d) and nested staining pattern were seen (e) (Laguesse, ×100). We, therefore, favored the diagnosis of a melanotic schwannoma with atypical features suggestive of aggressive behavior. Molecular analysis of this case did not reveal mutations in the GNAQ gene

Results of GNAQ mutational analysis

All lesions were tested for mutations in exon 5 of the GNAQ gene. The results are presented in Table 2. We detected mutations in exon 5 of GNAQ in three of four melanocytomas and the blue nevus (c626A>T, pGln209Leu). No mutations were detected in melanotic or conventional schwannomas. In the two lesions which we could not classify with certainty as melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma (cases 24 and 25), only case 25 (the probable melanocytoma case) had a mutation in codon 209 of exon 5 (c626A>T, pGln209Leu).

Diagnostic value of GNAQ mutational analysis

In our previous study on GNAQ mutations in primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions [16], codon 209 mutations of GNAQ were present in 7 of 19 lesions. Taking these previous results into account, a total GNAQ mutation frequency of 43% (10/23) in primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions was detected. No GNAQ mutations were detected in the melanotic schwannomas. The mutational status between melanotic schwannoma and leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions was significantly different (P = 0.030). GNAQ mutations were highly specific for leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions compared to melanotic schwannoma (100%); however, sensitivity for leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions was low (43%).

Discussion

Especially on biopsy material, the differential diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma with primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions and, in case of peripherally located lesions, cellular blue nevi can pose a problem to pathologists, since these lesions have overlapping histological features and immunohistochemical stains are not always useful. All these lesions are variably pigmented, spindle and/or epithelioid cell tumors, expressing S-100 (owing to their common neural crest origin) and one or more melanocytic markers. However, some histological features favor the diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma, such as circumscribed, often encapsulated growth, and/or the presence of psammoma bodies. Psammoma bodies are generally absent in melanocytic tumors, although one case of a psammomatous melanoma arising in an intradermal nevus has been described [18]. Stains for components of the basement membrane can be useful in discriminating tumors with schwannian differentiation from tumors with melanocytic differentiation [12]. Deposition of basement membrane material around individual tumor cells (‘pericellular’ pattern) is a feature of tumors with schwannian differentiation, and is generally not pronounced in melanocytic tumors [23, 26]. However, stains for basement membrane in melanin producing tumors should be interpreted with caution. First, in melanotic schwannomas, a biphasic staining pattern has been described with deposition of basement membrane material around both individual tumor cells as well as around nests of tumor cells [12], as was the case in five of nine melanotic schwannomas in our study. On biopsy material, with only limited tissue to evaluate, this might result in misinterpreting the lesion as a melanocytic tumor. Secondly, most melanomas show the absence of basement membrane material around individual tumor cells [26], except for spindle cell melanomas and desmoplastic neurotropic melanomas in which also a biphasic staining pattern has been described [4, 21, 26].

Recently, we reported the presence of activating mutations in codon 209 of the GNAQ gene in primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions [16]. This gene encodes the α-subunit of q class heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins which couple G-protein-coupled receptors to the MAP kinase pathway. Identical codon 209 mutations have been reported in uveal melanoma (46%) and blue nevi (83%) [28]. These codon 209 mutations occur in the ras-like domain turning GNAQ into a dominant acting oncogene [28]. The aim of the present study was to perform a thorough histological review of a series of lesions that were initially diagnosed as melanotic schwannoma and analyze these cases for mutations in the GNAQ gene. In addition, we evaluated the diagnostic value of GNAQ mutational analysis in the sometimes difficult differential diagnosis with primary leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions. Twenty-five cases initially diagnosed as melanotic schwannoma were reviewed and reclassified using established criteria into nine melanotic schwannomas, nine conventional schwannomas, four melanocytomas, one blue nevus and two lesions that could not be further classified with certainty as melanotic schwannoma or melanocytoma. The fact that in only 9 of 25 cases the initial diagnosis melanotic schwannoma remained unchanged after review illustrates the difficult differential diagnosis with esp. conventional schwannoma and leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions. Including results from our previous study [16], a total GNAQ mutation frequency of 43% was present in leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions (10/23). No GNAQ mutations were detected in the melanotic schwannomas (0/9). These results show that GNAQ mutations are highly specific for leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions compared to melanotic schwannoma (100%). Thus, GNAQ mutational analysis can have diagnostic value: in case a GNAQ mutation is present, this supports the diagnosis of a melanocytic lesion. Here, it is important to note that lack of a GNAQ mutation does not rule out the diagnosis of a melanocytic lesion. Correct diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma has clinical relevance as melanotic schwannoma can occur in the setting of the autosomal dominant Carney complex and may require additional clinical investigations. GNAQ codon 209 mutations in blue nevi have been reported in up to 83% [28]. This high mutation frequency suggests that GNAQ mutational analysis can also be useful in the differential diagnosis of peripherally located melanotic schwannoma with blue nevus. Noteworthy, we reclassified a substantial number of lesions initially diagnosed as melanotic schwannoma into conventional schwannoma (n = 9), based on the absence of staining for Melan-A and HMB-45. These lesions all contained some areas with fine intracytoplasmic grayish Schmorl positive pigment in tumor cells. However, the absence of staining for Melan-A and HMB-45 contradicts the presence of true melanosomes in these cells and suggests that the pigment is rather autophagosome-related (e.g. neuromelanin, lipofuscin) [11]. Care should thus be taken not to over-diagnose melanotic schwannoma in order to prevent unnecessary clinical work-up for Carney complex. At the moment, it is unclear why mutations in the GNAQ gene are especially found in a subgroup of melanocytic lesions, including leptomeningeal melanocytic lesions, uveal melanomas and blue nevi but not in cutaneous melanoma [16, 17, 28]. The fact that these GNAQ-mutated melanocytic lesions seem to be derived from non-epithelium related melanocytes may indicate that GNAQ mutations preferentially occur in melanocytes present in extra-epithelial structures such as leptomeninges, dermis and uvea. However, whether the site-specific occurrence of GNAQ mutations is a consequence of the mutations themselves or represents different target cell populations needs to be further determined. GNAQ codon 209 mutations seem to be an early event in the pathogenesis since they occur in benign as well as malignant melanocytic lesions. These activating codon 209 mutations form an alternative route for MAP kinase activation and probably represent an initial stimulus for melanocytes to proliferate. Inhibition of GNAQ-dependent MAP kinase signaling may form a novel option for targeted therapy of these tumors. In conclusion, this study illustrates the difficult differential diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma with leptomeningeal melanocytoma, and shows that a detailed analysis of morphology combined with molecular analysis of the GNAQ hotspot mutation can aid herein. Correct diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma is important to select those patients who need further clinical evaluation for possible association with Carney complex.

Acknowledgments

We thank the PALGA foundation, the national histopathology and cytopathology database in The Netherlands, for providing us with anonymized patient information. We are grateful to Clemens Prinsen, Mandy Wouters and Inge Arbeider for performing the DNA isolations, and Susan Van de Meer, Susan Noorlander, Renske Zenhorst, Coos Diepenbroeck and Monique Link for supervising and/or performing the histochemical and immunohistochemical stains. We thank Paul Rombout for his technical assistance with the molecular analyses and Peter de Wilde for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

H. V. N. Küsters-Vandevelde and I. A. C. H. van Engen-van Grunsven contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Brat DJ, Perry A. Melanocytic lesions. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2007. pp. 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brat DJ, Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Burger PC. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous systems. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:745–754. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns DK, Silva FG, Forde KA, Mount PM, Clark HB. Primary melanocytic schwannoma of the stomach. Evidence of dual melanocytic and schwannian differentiation in an extra-axial site in a patient without neurofibromatosis. Cancer. 1983;52:1432–1441. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831015)52:8<1432::AID-CNCR2820520816>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson JA, Dickersin GR, Sober AJ, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:478–494. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950115)75:2<478::AID-CNCR2820750211>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney JA. Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. A distinctive, heritable tumor with special associations, including cardiac myxoma and the Cushing syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:206–222. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrasco CA, Rojas-Salazar D, Chiorino R, Venega JC, Wohllk N. Melanotic nonpsammomatous trigeminal schwannoma as the first manifestation of Carney complex: case report. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:E1334–E1335. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000245608.07570.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casparie M, Tiebosch AT, Burger G, et al. Pathology databanking and biobanking in The Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol. 2007;29:19–24. doi: 10.1155/2007/971816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Bella C, Declich P, Assi A, et al. Melanotic schwannoma of the sympathetic ganglia: a histologic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Neurooncol. 1997;35:149–152. doi: 10.1023/A:1005883313651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong Q, Shenker A, Way J, et al. Molecular cloning of human G alpha q cDNA and chromosomal localization of the G alpha q gene (GNAQ) and a processed pseudogene. Genomics. 1995;30:470–475. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Font RL, Truong LD. Melanotic schwannoma of soft tissues. Electron-microscopic observations and review of literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:129–138. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda T, Igarashi T, Hiraki H, Yamaki T, Baba K, Suzuki T. Abnormal pigmentation of schwannoma attributed to excess production of neuromelanin-like pigment. Pathol Int. 2000;50:230–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang HY, Park N, Erlandson RA, Antonescu CR. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural comparative study of external lamina structure in 31 cases of cellular, classical, and melanotic schwannomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2004;12:50–58. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaehler KC, Russo PA, Katenkamp D, et al. Melanocytic schwannoma of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues: three cases and a review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:438–442. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32831270d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirschner LS, Sandrini F, Monbo J, Lin JP, Carney JA, Stratakis CA. Genetic heterogeneity and spectrum of mutations of the PRKAR1A gene in patients with the carney complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:3037–3046. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krausz T, Azzopardi JG, Pearse E. Malignant melanoma of the sympathetic chain: with a consideration of pigmented nerve sheath tumours. Histopathology. 1984;8:881–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1984.tb02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusters-Vandevelde HV, Klaasen A, Kusters B, et al. Activating mutations of the GNAQ gene: a frequent event in primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;119:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamba S, Felicioni L, Buttitta F, et al. Mutational profile of GNAQQ209 in human tumors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteagudo C, Ferrandez A, Gonzalez-Devesa M, Llombart-Bosch A. Psammomatous malignant melanoma arising in an intradermal naevus. Histopathology. 2001;39:493–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mooi WJ, Krausz T. Blue nevus and related lesions. In: Mooi WJ, Krausz T, editors. Pathology of melanocytic disorders. 2. London: Hodder Arnold; 2007. pp. 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mooi WJ, Krausz T. Other extracutaneous melanotic tumors. In: Mooi WJ, Krausz T, editors. Pathology of melanocytic disorders. 2. London: Hodder Arnold; 2007. pp. 451–454. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prieto VG, Woodruff JM. Expression of basement membrane antigens in spindle cell melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:297–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1998.tb01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross EM, Wilkie TM. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:795–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaumburg-Lever G, Lever I, Fehrenbacher B et al (2000) Melanocytes in nevi and melanomas synthesize basement membrane and basement membrane-like material. An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study including immunoelectron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol 27:67–75 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Scheithauer BW, Louis DN, Hunter S, Woodruff JM, Antonescu CR. Schwannoma. In: Louis DN, Oghaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2007. pp. 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheithauer BW, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA. Tumors of the peripheral nervous system. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmoeckel C, Stolz W, Sakai LY, Burgeson RE, Timpl R, Krieg T. Structure of basement membranes in malignant melanoma and nevocytic nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92:663–668. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12696845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Wassef M, Lot G, et al. Spinal melanotic schwannoma: a tumour with poor prognosis. Histopathology. 1999;35:558–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009;457:599–602. doi: 10.1038/nature07586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veugelers M, Wilkes D, Burton K, et al. Comparative PRKAR1A genotype-phenotype analyses in humans with Carney complex and prkar1a haploinsufficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14222–14227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405535101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]