Sirs,

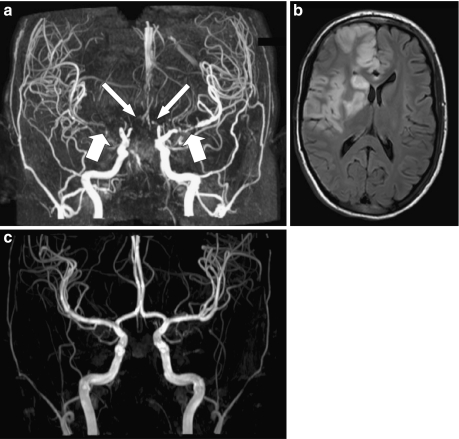

The oldest of three sisters, two of whom are monozygous twins, presenting all with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) associated with a CFH mutation, was referred at the age of 3 years to the Emma Children’s Hospital/Academic Medical Centre of Amsterdam (Fig. 1) [1, 2]. She never recovered renal function and commenced peritoneal dialysis. Bilateral nephrectomy was performed 1 year later because of hypertension. She lost two transplants by recurrence, one immediately posttransplantation and the other one 2 months posttransplant despite preventive plasma exchanges (PEs) contemporary to frequency reduction of PE. From the age of 15 years, she began to experience transient sensory and motor symptoms on both sides of her body associated with low blood pressure (BP) during hemodialysis. Magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) showed severe stenoses of both middle and both anterior cerebral arteries (Fig. 2a) (partial report in [3]). She did not present any additional risk factors for developing arteriosclerosis (such as long-duration hypertension, diabetes, uncontrolled hyperparathyroidism). No arterial calcification and no left ventricular hypertrophy were shown.

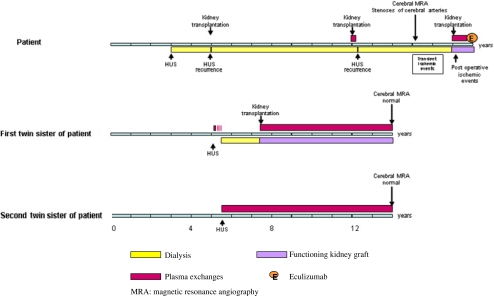

Fig. 1.

Clinical course in patient and her twin sisters

Fig. 2.

Three-Tesla magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of patient 2 (a, b) and her sister (c). Coronal 3D time-of flight (TOF) MRA maximum intensity projection (MIP) (a) image of patient at the age of 15 years demonstrates (near) occlusion of the M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery (thick arrow) and the A1 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery (long arrow), and severe stenosis of the M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (thick arrow) and the A1 segment of the left anterior cerebral artery (long arrow). Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI (b) of the patient at the age of 17 years shows infarct in right middle and anterior cerebral arteries. Coronal 3D TOF MRA MIP image (c) of the sister of patient 2 at the age of 14 years shows normal appearance of intracranial arteries. Basilar artery and side branches were manually removed from the 3D data sets in a and c to better demonstrate the anterior cerebral arteries

At the age of 17 years, the patient was transplanted for the third time under pre- and postoperative prophylactic PEs [1, 2]. Postoperatively, she developed infarcts in the right frontal and frontoparietal regions (Fig. 2b). She recovered almost completely. Ten months after transplantation, the child developed bronchospasm and hypotension during PE. For this reason, she was switched to eculizumab [2]. Under this treatment, she presented no HUS recurrence, and renal function remained stable (plasma creatinine 120 μmol/L) 16 months after PE discontinuation. The first of her twin sisters (twin 1) developed aHUS at the age of 5.3 years. She required chronic dialysis despite initial daily PE for 10 days and three intermittent courses of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) infusions. Two years later, she received a cadaver renal transplant under PE prophylaxis. At 7.5 years follow-up, the graft function is satisfactory (serum creatinine 137 μmol). The second twin (twin 2) presented aHUS at the age of 5.8 years (Fig. 1) [1]. She was treated immediately with daily PE and, following remission, with one PE every 2 weeks to this time. At 9.5 years after HUS onset, native renal function (serum creatinine 49 μmol/L) was normal. MRA showed normal cerebral vasculature in both twins at age 14 years (Fig. 2c). Contrary to their older sister with cerebral artery stenoses who was treated by prophylactic PE for 2 months only, the twin sisters received prophylactic PE without interruption for, respectively, 7.5 (twin 1) and 9 (twin 2) years.

Although brain ischemia sometimes resulting in cerebral infarct is observed in aHUS, stenosis of large vessels has been reported in aHUS only once—in a child presenting with a Lys350Asp gain of function CFB mutation [4]. Of note, this patient, as ours, was dialyzed for long periods from the age of 4 months. At the age of 10 years, she started having episodes of bilateral hemiparesis during hemodialysis in relation with multiple stenoses of cerebral arteries. Stenoses of large arteries have never been reported as a complication of renal replacement therapy (RRT) in children [5]. Chronic continuous complement dysregulation might contribute to vascular lesions. Indeed complement activation occurs both in human and experimental atherosclerosis, and the deposition of C5b-9 correlates with disease state [6].

Our patient and the patient reported recently by Loirat et al. [4] suggest that aHUS with complement dysregulation, a disease of microvascularization, may also involve large arteries, especially when patients have to face long periods of dialysis when plasma therapy is not used. The latter reports also raise the question of preventing vascular lesions by avoiding complement system disorders. This emphasizes the importance of including patients at an early stage in specific programs of kidney transplantation using preventive plasma therapy or combined liver transplantation. Inhibition of the complement system by anti-C5 antibody that is actually under investigation might be valuable for this purpose in the future [2].

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Davin JC, Strain L, Goodship TH. Plasma therapy in atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome: lessons from a family with a factor H mutation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1517–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0833-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davin JC, Gracchi V, Bouts A, Groothoff JW, Strain L, Goodship T. Maintenance of kidney function following treatment with eculizumab and discontinuation of plasma exchange after a third kidney transplant for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with a CFH mutation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;55:708–711. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vergouwen MD, Adriani KS, Roos YB, Groothoff JW, Majoie CB. Proximal cerebral artery stenosis in a patient with haemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:e34. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loirat C, Macher MA, Elmaleh-Berges M, Kwon T, Deschênes G, Goodship TH, Majoie C, Davin JC, Blanc R, Savatovsky J, Moret J, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. Non-atheromatous arterial stenoses in atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome associated with complement dysregulation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson AC, Mitsnefes MM. Cardiovascular disease in CKD in children: update on risk factors, risk assessment, and management. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:345–360. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haskard DO, Boyle JJ, Mason JC. The role of complement in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:478–482. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32830f4a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]