Abstract

Pulmonary arteries (PA) constrict in response to alveolar hypoxia, whereas systemic arteries (SA) undergo dilation. These physiological responses reflect the need to improve gas exchange in the lung, and to enhance the delivery of blood to hypoxic systemic tissues. An important unresolved question relates to the underlying mechanism by which the vascular cells detect a decrease in oxygen tension and translate that into a signal that triggers the functional response. A growing body of work implicates the mitochondria, which appear to function as O2 sensors by initiating a redox-signaling pathway that leads to the activation of downstream effectors that regulate vascular tone. However, the direction of this redox signal has been the subject of controversy. Part of the problem has been the lack of appropriate tools to assess redox signaling in live cells. Recent advancements in the development of redox sensors have led to studies that help to clarify the nature of the hypoxia-induced redox signaling by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Moreover, these studies provide valuable insight regarding the basis for discrepancies in earlier studies of the hypoxia-induced mechanism of redox signaling. Based on recent work, it appears that the O2 sensing mechanism in both the PA and SA are identical, that mitochondria function as the site of O2 sensing, and that increased ROS release from these organelles leads to the activation of cell-specific, downstream vascular responses.

1. Introduction

Pulmonary arteries (PA) constrict in response to alveolar hypoxia, as part of a response termed hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV). The HPV response was first described in 1946 by von Euler and Liljestrand, who found that PA pressure increased in feline lungs ventilated with low O2 mixtures, and decreased when ventilated with pure O2 (von Euler and Liljestrand, 1946). Recognizing that these responses reflected changes in pulmonary vascular resistance, they speculated that a vasoconstrictor response to hypoxia could help to improve gas exchange efficiency by diverting blood flow away from poorly ventilated lung regions and towards areas with better oxygenation. While this response may improve gas exchange when the hypoxia is limited to small regions, widespread hypoxia throughout the lung elicits pulmonary arterial hypertension. This response is beneficial in the fetus, where the diversion of blood away from the lung prevents oxygen loss from pulmonary capillary blood to hypoxic alveolar amniotic fluid. However, in adult lungs the development of global alveolar hypoxia, which can occur at high altitude or in hypoxic lung diseases, leads to chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension that can trigger pulmonary vascular remodeling as well as right ventricular hypertrophy. Unlike pulmonary arteries, systemic arteries relax in response to tissue hypoxia. This response facilitates local arterial vasodilation, thereby enhancing blood flow and oxygen supply in hypoxic tissues (Detar, 1980; Gupte and Wolin, 2008; Guyton et al., 1964; Michelakis et al., 2002; Weir et al., 1997).

A large number of studies have examined the responses to hypoxia in the pulmonary and systemic circulations. In the lung, the HPV response is retained in excised lungs, in lung slices, and in PA rings studied in an organ bath (Archer et al., 1993; Desireddi et al., 2010; Grimminger et al., 1995; Leach et al., 2001; Marshall et al., 1996; McMurtry, 1984; Robertson et al., 2001; Rounds and McMurtry, 1981; Weissmann et al., 1998; Weissmann et al., 1995; Zhao et al., 1996). Isolated PA smooth muscle cells (PASMC) also contract under hypoxia, indicating that these cells are O2 – sensitive (Lu et al., 2009; Shimoda et al., 2007; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2010; Waypa et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 1997). Likewise, the systemic vascular responses to hypoxia are evident in isolated systemic arterial smooth muscle cells (SASMC) (Coburn, 1977; Franco-Obregon et al., 1995; Mehta et al., 2008; Michelakis et al., 2002; Smani et al., 2002; Waypa et al., 2010), indicating that these, too, possess an O2 sensor. Despite the wealth of information characterizing these responses, the identity of the O2 sensor(s) is not established. Several previous reviews have dealt with this question, and the reader is directed to them for a broader perspective of this field (Evans, 2010; Evans and Ward, 2009; Gupte and Wolin, 2008; Sommer et al., 2008; Ward and McMurtry, 2009; Waypa and Schumacker, 2008; Weir et al., 2008; Wolin, 2009).

The goal of the present review is to provide an analysis of data examining the acute response to hypoxia in the pulmonary and systemic vasculature. With respect to the HPV response, a growing body of work implicates the mitochondria as the site of O2 sensing, although the general idea that mitochondria could play such a role is not new. From a parsimonious standpoint it is appealing to predict that a similar mechanism of oxygen sensing could function in both the pulmonary and systemic vascular beds, as the biophysical process of oxygen sensing signal transduction is necessarily complex and the range of possible molecular mechanisms seems limited. However, in view of the heterogeneity of cells in the vascular wall, the diversity of functional responses to hypoxia that have been described in vascular cell types, and the broad range of responses to acute versus chronic hypoxia, it seems unlikely that a single oxygen sensing system is involved. Nevertheless, the definitive identification of even one oxygen sensing mechanism and the mechanisms coupling that sensor to a single functional response would represent an important scientific achievement.

2. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction

2.1 The HPV response

The HPV response in pulmonary arteries is biphasic (Dipp et al., 2001; Leach et al., 2001). An initial transient constriction (acute phase) is followed by a slow sustained constriction (chronic phase). This response is associated with a biphasic rise in [Ca2+]i in PASMC (Robertson et al., 1995). The acute phase, which occurs within seconds of a hypoxic challenge, does not require an intact endothelium (Zhang et al., 1997) and likely involves the release of calcium from intracellular stores, closure of voltage-dependent potassium channels (KV), and opening of both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent calcium channels [also known as non-selective cation channels (NSCC)] (Archer et al., 1998; Lu et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2008; Morio and McMurtry, 2002; Robertson et al., 2000b). The hypoxia-induced increase in cytosolic calcium activates myosin light chain kinase, causing actin-myosin interaction and PASMC contraction. The chronic phase occurs within minutes after hypoxic challenge and can persist for hours to days, if hypoxia is maintained. This response requires the endothelium, indicating that an endothelial-derived promoting factor may be involved (Aaronson et al., 2002; Dipp et al., 2001; Lazor et al., 1996; Leach et al., 2001; Leach et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2001; Ward and Robertson, 1995). Endothelial denudation does not alter the calcium response to chronic hypoxia; rather, it affects the myofilament sensitivity to [Ca2+]i in PASMC (Robertson et al., 1995). Calcium sensitivity in PASMC is regulated in part by myosin phosphatase, which is regulated by Rho kinase activity. Thus, inhibition of Rho kinase with Y-27632 attenuates the chronic phase of HPV in isolated PA and in perfused lungs (Robertson et al., 2000a). Rho kinase activity increases in isolated PASMC challenged with hypoxia (Chi et al., 2010), but the effect is amplified in the presence of endothelium (Wang et al., 2001), presumably due to the release of an endothelial-derived factor. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) may contribute to that effect (Liu et al., 2001), as the release of ET-1 is augmented during hypoxia (Bodi et al., 1995; Hu et al., 1998; Yamashita et al., 2001), and the ET-1 receptor subtype A antagonist, BQ-123, attenuates the chronic phase of HPV in intact PA vessels (Liu et al., 2001; Sato et al., 2000). Finally, ET-1 increases Rho kinase activity in PASMC (Barman, 2007; Homma et al., 2007; Weigand et al., 2006). As yet unidentified endothelial-derived factors may act in concert with ET-1 during the chronic phase (Aaronson et al., 2002; Robertson et al., 2003; Robertson et al., 2001). However, this review focuses on the acute phase of HPV, and the O2 sensor regulating the immediate response to hypoxia.

2.2 Mitochondria as the HPV oxygen sensor

The idea that mitochondria could act as oxygen sensors arose from the expectation that hypoxia should inhibit the mitochondrial electron chain (ETC) at Complex IV. Oxygen limitation of Complex IV could affect the redox state of the upstream electron carriers, which then might signal through an increase in the reduction of mitochondrial electron carriers such as β-NADH, a decrease in [ATP] and energy charge, or changes in cytosolic [NADH]:[NAD+] redox. If true, then mitochondrial inhibition should mimic hypoxia and trigger HPV. Indeed, Rounds and McMurtry found that certain inhibitors of the ETC and oxidative phosphorylation mimicked the hypoxia response in isolated, blood-perfused lungs, possibly by depleting [ATP] (Rounds and McMurtry, 1981). However, studies in isolated lungs by Buescher et al. and in isolated PA by Leach et al. demonstrated that the energy state does not decline during hypoxia in either of these systems (Buescher et al., 1991; Leach et al., 2000). Those findings suggest that decreases in [ATP] are not required for triggering HPV. Moreover, mitochondrial respiration remains constant until the extracellular PO2 falls below a critical threshold of 5–7 torr in diverse cell types (Jones and Kennedy, 1982, 1986). It therefore it seems unlikely that energy supply in PASMC would become O2-limited at oxygen tensions in the range of 10–40 torr where HPV is activated.

2.3 Does hypoxia decrease mitochondrial ROS signaling?

In 1986, Archer and Weir proposed that redox regulates membrane K+ channels and that a decrease in ROS would induce membrane depolarization by causing closure of those channels (Archer et al., 1986). They later suggested that mitochondria could act as O2 sensors by slowing their rate of ROS production during hypoxia, and increasing the rate during normoxia. This concept was supported by studies where they measured reciprocal changes in PA pressure and ROS levels during hypoxia or normoxia in perfused lungs, using lucigenin or luminol chemiluminescence to detect ROS generation (Archer et al., 1993). They also found that antimycin A and rotenone, agents that inhibit the ETC, caused chemiluminescence to decrease and PA pressure to increase acutely (Archer et al., 1993). Those findings led them to postulate that the mitochondrial ETC generates constitutive ROS during normoxia, and that the decrease in production during hypoxia leads to a reductive shift that causes vasoconstriction through the closure of KV+ channels (Archer and Michelakis, 2002; Archer et al., 1993). Also, Reeve et al. reported that the Complex I inhibitor rotenone decreased chemiluminescence and increased vascular tone in isolated perfused lungs (Reeve et al., 2001).

They explained the response to antimycin A and rotenone by proposing that these inhibitors decrease mitochondrial ROS generation (Archer and Michelakis, 2002; Archer et al., 1993). In endothelium-denuded rings of distal PA they also observed hypoxia-induced decreases in ROS as assessed by chemiluminescence, Amplex Red (an H2O2-sensitive reagent), and dichlorofluorecein (DCF, a non-specific oxidant-sensitive probe) (Michelakis et al., 2002). They also postulated that ROS could originate from NAD(P)H oxidase, which would presumably decrease its production of superoxide during hypoxia due to a fall in the availability of O2 (Archer and Michelakis, 2002). However, mice with targeted deletion of the gp91phox subunit (NOX2) of NADPH oxidase still exhibited HPV (Archer et al., 1999), indicating that NOX2 was not required for the hypoxic response.

Archer and Weir then proposed that hypoxia could slow mitochondrial electron transport, possibly decreasing ROS production by Complex I and/or Complex III while increasing cytosolic [NAD(P)H]/[NAD+] (Archer et al., 1993; Michelakis et al., 2002). This would shift the cytosolic [NADH]:[NAD+] redox balance to a more reduced state, which they theorized would somehow also shift the glutathione redox pool ([GSH]/[GSSG]) toward a reduced state (Weir and Archer, 1995), although those systems are not directly coupled. According to that model, mitochondrial inhibitors would be expected to mimic hypoxia by augmenting NAD(P)H levels and decreasing ROS during hypoxia. A perplexing aspect of that idea is that increases in NAD(P)H might be expected to augment ROS production by enhancing the activity of NAD(P)H-dependent systems other than NOX2. In either case, they claim that a reductive shift in redox during hypoxia results in the inhibition of K+ current through redox-sensitive 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)-sensitive KV channels (Reeve et al., 1995). Indeed, Rettig et al. had identified a cysteine residue in the β-subunit of the KV1-type channel expressed in rat brain that was oxidized by H2O2 (~40 mM) and reduced by glutathione (5 mM) (Rettig et al., 1994). When the cysteine residue is reduced, the NH2-terminal inactivating domain of the β-subunit binds to the inner mouth of the channel pore formed by the α-subunits of the KV channel causing the inactivation of the channel. Extrapolating those findings to pulmonary vascular smooth muscle, severe oxidant stress during normoxia might keep the KV channel in an activated state, whereas a reductive stress during hypoxia might cause channel closure, leading to membrane depolarization, the opening of L-type, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and subsequent myocyte contraction. In support of that hypothesis, they found that the powerful oxidants diamide (1 µM) or dithionitrobenzoic acid (1 mM) caused vasodilation in isolated perfused lungs and PA rings (Olschewski et al., 2004; Reeve et al., 1995; Weir et al., 1985), while the equally powerful reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT; 3 mM) and the antioxidants co-enzyme Q10 (700 µM) and duroquinone (700 µM) attenuated K+ currents in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells resulting in their contraction (Olschewski et al., 2004; Reeve et al., 1995). Finally, hypoxia was reported to cause inhibition of steady-state whole-cell K+ currents and membrane depolarization in rat PA smooth muscle cells (Olschewski et al., 2002a; Olschewski et al., 2002b; Olschewski et al., 2004). However, the molecular identities of the KV channel(s) that participate in those responses have not been fully identified.

That redox theory was based on the expectation that a decrease in oxygen would result in a decrease in ROS signaling. However, a more critical evaluation of that model raises important questions. First, mounting evidence reveals that the cell normally maintains a highly reduced thiol redox state in the cytosol (Gilbert, 1990), making signaling via further reductive stress unlikely. Moreover, signaling events triggered by angiotensin II, growth factors, and mechanical strain in vascular cells require increases ROS generation (Ali et al., 2004; Cowan et al., 2003; Lassegue et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2003; Marshall et al., 1996; Paddenberg et al., 2003; Waypa et al., 2001). Second, chemical inhibitors of KV channels as well as specific KV knockout mouse strains have failed to inhibit HPV, suggesting that (a) multiple KV channel types are involved, and/or (b) that closure of KV channels represents a downstream amplification step, rather than an initiating step, in HPV (Archer et al., 2001; Hasunuma et al., 1991; Sham et al., 2000). Third, modeling studies suggest that hypoxic inhibition of K+ currents (IKV and IKCa) is insufficient to induce PAMSC contraction unless it occurs in combination with NSCC activation (Cha et al., 2008). In addition, other investigators report that rotenone decreases ROS production while antimycin A augments oxidant generation (Chandel et al., 2000b; Chen et al., 2003; Cowan et al., 2003; Garcia-Ruiz et al., 1997; Mohazzab and Wolin, 1994; Turrens et al., 1985). Therefore, according to the model of Archer et al. (Archer et al., 1993; Michelakis et al., 2002), the former compound should have activated HPV while the latter should have blocked it. Finally, if decreases in intracellular ROS production trigger HPV, then antioxidants that scavenge ROS should trigger HPV during normoxia by lowering the levels of oxidant signaling. Instead, antioxidants block the response to hypoxia in intact lungs, isolated PA vessels and isolated PA smooth muscle cells, without causing a sustained increase in pulmonary vascular tone (Liu et al., 2003; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2002). Collectively, these observations question the idea that hypoxia-induced decreases in ROS trigger HPV.

2.4 Does hypoxia increase ROS signaling?

In 1996, Marshall et al. argued that hypoxia accelerates ROS generation by NADPH oxidase, based on their observation that diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) inhibited the oxidant signal in PASMC and the contractile response to hypoxia (Marshall et al., 1996). This finding was confirmed by other investigators in cultured PASMC and isolated lungs (Grimminger et al., 1995; Thompson et al., 1998; Waypa et al., 2001). However, DPI inhibits all flavoproteins including NADPH oxidase, mitochondrial Complex I, glutathione reductase, nitric oxide synthase, and prostaglandin synthetase (Holland et al., 1973; Majander et al., 1994). Therefore, the site of inhibition responsible for the attenuation of HPV is not known. To clarify the involvement of an NAD(P)H oxidase in HPV, two groups used apocynin, an inhibitor of the neutrophil form of this enzyme (Grimminger et al., 1995; Waypa et al., 2001). As with mice lacking the gp91phox subunit of the NADPH oxidase, apocynin failed to block the HPV response. However, these results do not rule out that possibility that other NAD(P)H oxidase-like systems could still be involved in HPV. In accordance with this reasoning, Weissmann et al. demonstrated a decrease in HPV by the NOX inhibitor [4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride], while Jones et al. inhibited HPV in isolated rat PA using cadmium sulfate to inhibit the proton translocation channel of the NOX-2 (NADPH oxidase) complex (Jones et al., 2000; Weissmann et al., 2000). More recently, Weissmann et al. studied the effects of hypoxia on lungs from mice deficient in the NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox, which is suggested to be a key subunit for the function of most NADPH oxidase isoforms (Weissmann et al., 2006b). They observed an attenuation of the acute phase of HPV in perfused lungs isolated from NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox deficient mice compared to wild type and NADPH oxidase subunit gp91phox mice (Weissmann et al., 2006b). This supports the concept that a non-phagocytic NADPH oxidase-derived increase in ROS is involved in triggering the acute phase of HPV.

After the report from Marshall et al., other studies also suggested that acute hypoxia triggers an increase in ROS signaling in PASMC, as measured by the intracellular probe 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin-diacetate (DCFH), lucigenin-derived chemiluminescence and by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectrometry, although the latter results did not achieve statistical significance (Killilea et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007; Waypa et al., 2001). Moreover, antioxidants such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase attenuated the HPV response while others, like superoxide dismutase (SOD), had either no effect or augmented the response (Wang et al., 2007; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2010; Waypa et al., 2002). Weissmann et al. observed that SOD or 4,5- dihydroxy-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid (to accelerate H2O2 generation from superoxide) did not affect HPV, suggesting that H2O2, rather than superoxide, is involved (Weissmann et al., 1998). Also, nitrobluetetrazolium, a putative trap for superoxide, prevented H2O2 formation and attenuated HPV (Weissmann et al., 1998). The involvement of increased ROS is further indicated by the observation that exogenous H2O2 mimics HPV in cultured PASMC and in isolated lungs (Pourmahram et al., 2008; Sheehan et al., 1993; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2002; Waypa et al., 2000), although it should be noted that H2O2 can also release Ca2+ from mitochondria (Richter et al., 1995) and may also trigger nonspecific effects (Jin et al., 1991; Rhoades et al., 1990). Nevertheless, these findings support the idea that an increase in a ROS signaling occurs during HPV.

The idea that HPV requires electron transport in the proximal but not the distal region of the mitochondrial ETC comes from the observation that upstream inhibitors such as rotenone or myxothiazol abrogate HPV (Wang et al., 2007; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002; Weissmann et al., 2003), whereas inhibitors acting at more distal sites, such as cyanide or antimycin A, fail to inhibit the response. Leach et al. extended this observation by showing that rotenone blocked hypoxic contraction of PA vessels, and that HPV could subsequently be restored by using succinate to shuttle electrons into Complex III via Complex II, bypassing the site of inhibition (Leach et al., 2001). That inhibitors of the distal ETC do not abolish HPV suggests that a fully functional ETC is not required for the hypoxic response (Leach et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002). These site-specific effects can be explained by the inability of some compounds to prevent hypoxia-induced increases in ROS production from the proximal region of the ETC, notably Complex III (Chandel et al., 1998; Waypa et al., 2006). For example, antimycin A, which blocks the downstream Qi site in Complex III and thereby augments ROS production from that Complex, triggers vasoconstriction in normoxic lungs (Rounds and McMurtry, 1981). Cyanide, which inhibits cytochrome oxidase and thereby causes reduction of the entire ETC, enhances ROS production throughout the ETC and causes constriction during normoxia (Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002). It also triggers [Ca2+]i increases in PASMC (Wang et al., 2003; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002). Interestingly, Archer et al. found that cyanide induced vasoconstriction during normoxia and augmented HPV without affecting the response to angiotensin II or KCl (Archer et al., 1993). This response can be blocked by myxothiazol, which prevents electron flow into Complex III, and by over-expression of catalase (Waypa et al., 2002), which augments the scavenging of H2O2.

While these findings are consistent with a role for increased ROS production in HPV, many of these studies rely on pharmacological inhibitors whose effects can vary depending on concentration. Indeed, some laboratories have reported that mitochondrial inhibitors mimic HPV (Archer and Michelakis, 2002; Archer et al., 1993), while others show that they attenuate the HPV response (Leach et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2001). To address this, ρ0-PASMC, which lack a functional ETC and are incapable of generating ROS during hypoxia, have been studied. These cells lose their hypoxic response, yet retain the ability to respond to U46619, a thromboxane A2 analogue (Waypa et al., 2001). Increasingly, genetic deletion of genes involved in redox regulation provides more definitive evidence that the ETC plays a physiologically conserved role in hypoxia-induced ROS signaling and hypoxic responses such as the stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) (Guzy et al., 2005; Mansfield et al., 2005).

2.5 Critical assessment of ROS signaling during HPV

The finding that hypoxia increases ROS generation is not limited to PASMC, as it has been observed in a wide variety of cell types (Chandel et al., 1998; Chandel et al., 2000a; Duranteau et al., 1998; Killilea et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2001). Technical limitations of the tools used to assess oxidant stress have fueled the disagreements regarding ROS signaling during hypoxia. Fluorescent probes such as DCF and dihydroethidium lack specificity (Thannickal and Fanburg, 2000) and can accumulate within organelles, while autoxidation and limited intracellular access can interfere with the ability of lucigenin or luminol to detect intracellular oxidants (Spasojevic et al., 2000). Importantly, none of these probes exhibits ratiometric fluorescence properties, so changes in intracellular dye concentration or fluorescence path length caused by a change in cell volume can affect fluorescence intensity independently from changes in ROS. Investigators are increasingly employing a new generation of ratiometric, redox-sensitive probes to assess ROS signaling during hypoxia. One such probe uses Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and consists of enhanced cyan and yellow fluorescent protein motifs (CFP, YFP) linked by the redox-dependent regulatory domain from the bacterial heat shock protein HSP-33 (Janda et al., 2004). The HSP-33 domain contains four highly conserved cysteine residues coordinating a zinc-binding domain. Oxidation of the thiols leads to release of zinc and the formation of two disulfides (Barbirz et al., 2000). Using the redox-dependent regulatory domain from HSP-33, a ratiometric redox reporter was generated (HSP-FRET), in which oxidation causes a change in the optical coupling of CFP and YFP (Guzy et al., 2005). When expressed in cells, HSP-FRET provides a sensitive, real-time assessment of changes in redox in the cytosol in response to hypoxia (Waypa et al., 2006). In cultured PASMC expressing HSP-FRET, superfusion with hypoxic media caused an increase in ROS signaling in the cytosol (Waypa et al., 2006). This response was attenuated by myxothiazol, catalase or glutathione, yet neither cyanide nor SOD altered hypoxia-induced increase in ROS signaling (Waypa et al., 2006). Interestingly, changes in hypoxia-induced ROS signaling were mirrored by changes in [Ca2+]i, and attenuation of the ROS signal abrogated the calcium response (Waypa et al., 2006). However, a characteristic of HSP-FRET protein is that it refolds slowly after being oxidized, hindering the ability to calibrate its redox state. Furthermore, attempts to target its expression to the mitochondria were unsuccessful, impeding its usefulness for assessing sub-cellular redox signaling.

Another redox sensor, roGFP, provides an alternative measure of protein thiol redox status (Cannon and Remington, 2009; Dooley et al., 2004; Hanson et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2006; Lohman and Remington, 2008). Oxidation resulting in dithiol formation causes reciprocal changes in its emission intensity when excited at two different wavelengths. By exposing cells to strong reducing and oxidizing agents at the conclusion of an experiment, roGFP oxidation state can be calibrated on a cell-by-cell basis.

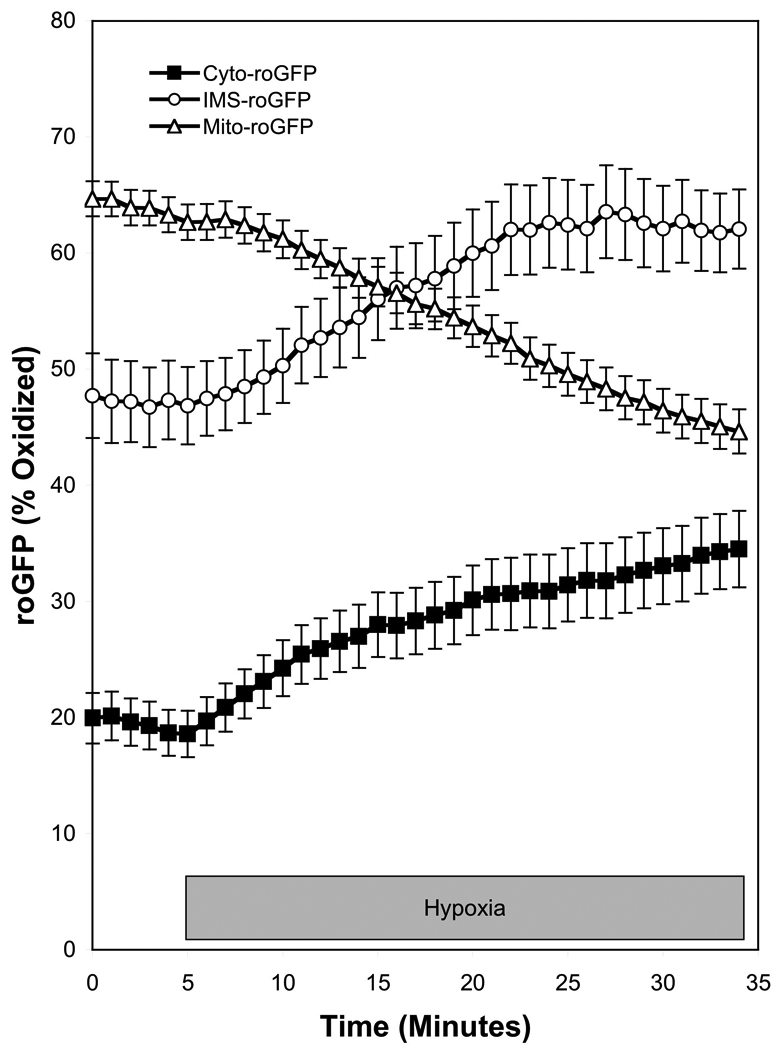

We generated constructs to target roGFP to the mitochondrial matrix, the inter-membrane space (IMS), and the cytosol (Waypa et al., 2010). Under normoxic conditions the cytosol was highly reduced and the matrix was the most oxidized, while the IMS demonstrated an intermediate level of protein thiol oxidation (Figure 1) (Waypa et al., 2010). During hypoxia, roGFP oxidation in the cytosol and the IMS demonstrated an oxidative shift (Figure 1). However, the oxidant signal was subtle and it produced a relatively small change in protein thiol oxidation state. By contrast, roGFP oxidation in the matrix decreased. The increase in ROS signaling in the IMS and cytosol despite the decrease in O2 suggests that this is a regulated event, whereas the general O2-dependent decrease in oxidation in the matrix suggests that ROS production in that compartment is a non-specific unregulated process. The hypoxia-induced increase in cytosolic ROS signaling was associated with a rise in [Ca2+]i, which was attenuated by over-expression of cytosolic catalase, implicating H2O2 involvement. Similar responses to acute hypoxia were measured when roGFP was expressed in the PASMC of mouse lung slices (Desireddi et al., 2010). Furthermore, it was observed that the hypoxia-induced oxidation of roGFP is maintained when PASMC are incubated under prolonged (24 hrs) hypoxic conditions (Chi et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Hypoxia increases regulated ROS signaling in the cytosol and IMS of PASMC while decreasing non-specific ROS signaling in the mitochondrial matrix. The redox sensor roGFP was targeted to the cytosol (Cyto-roGFP), the intermembrane space of mitochondria (IMS-roGFP), and the mitochondrial matrix (Mito-roGFP) of PASMC, which were then superfused under controlled O2 conditions. Hypoxia (1.5% O2) caused an increase in the oxidation of roGFP in the cytosol and IMS, while it decreased oxidation in the mitochondria matrix. (Data replotted from a previously published report (Waypa et al., 2010)).

The compartment-specific redox responses do provide insight into the basis for disagreements among investigators regarding ROS generation in hypoxia. Probes such as lucigenin may not enter the cells, or could accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix. By contrast, probes such as DCF may remain in the extracellular space or can be taken up into the cytosol, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, or other compartments. Once oxidized, many fluorescent probes can migrate between compartments. Thus, depending on where it accumulates, the overall cellular fluorescence/luminescence behavior of a chemical probe could provide a distorted picture of what is occurring in a given region. More importantly, the combined signal would be dominated by large compartments where large shifts occur, and may not detect smaller changes in ROS in specific compartments where they act in a signaling function. To the extent that redox responses differ among subcellular compartments, the unknown and varying distribution of chemical probes among compartments could easily explain why different experiments have yielded inconsistent responses among laboratories. Protein sensors, by contrast, are only expressed in the cells. Immunogold electron microscopy studies confirm the expected targeted expression patterns, and the distribution within the cell does not change over time (Waypa et al., 2010). Importantly, the ability to calibrate the roGFP sensor permits comparisons between cells, and among intracellular compartments. Clearly, more experiments using imprecise tools that provide ambivalent answers are not likely to advance this field.

2.6 Hypoxia-induced ROS signaling triggers the calcium response

While hypoxia-induced increases in [Ca2+]i could arise from the entry of extracellular Ca2+ through voltage-dependent and/or voltage-independent Ca2+ channels (Archer et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2002, 2003; Post et al., 1995; Robertson et al., 2000b; Wang et al., 2004), recent studies suggest that an initial intracellular release of Ca2+ may then trigger extracellular entry (Dipp and Evans, 2001; Dipp et al., 2001; Morio and McMurtry, 2002; Salvaterra and Goldman, 1993; Weigand et al., 2005). Possible sources of intracellular release include the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and/or mitochondria. Hypoxia-induced release of Ca2+ from SR could be mediated by ryanodine receptors (RyR) and/or inositol 1,4,5- trisphosphate (IP3) receptors. Li et al. demonstrated that the increase in [Ca2+]i during hypoxia was attenuated in RyR−/− and RyR+/− mice (Li et al., 2009). RyR contain redox-sensitive cysteine thiols (Eu et al., 1999), so ROS released from mitochondria could trigger Ca2+ release by activating these channels. In support of this idea, low concentrations of peroxide have been shown to elevate [Ca2+]i via release from RyR-sensitive stores (Lin et al., 2007; Pourmahram et al., 2008; Rathore et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2007). Alternatively, early calcium increases may reflect SR Ca2+ release through stimulation of RyR by cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) (Dipp and Evans, 2001; Evans and Dipp, 2002). In that model, hypoxia-induced inhibition of ATP production would increase the AMP/ATP ratio, thereby activating AMPK and increasing production of cADPR (Evans and Ward, 2009). However, ROS and AMPK may also be linked in a system whereby ROS triggers AMPK activation (Quintero et al., 2006). Hence, cADPR-dependent Ca2+ release from the SR could occur as a downstream consequence hypoxia-induced increases in ROS. Alternatively, activation of IP3 receptors could trigger Ca2+ release from the SR, based on the ability of ROS to activate phospholipase C (PLC) (Gonzalez-Pacheco et al., 2002). PLC generates diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) from phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2).

Hypoxia-induced calcium release from the SR may then trigger voltage-dependent and/or voltage-independent calcium entry, thereby amplifying the acute constriction response (Post et al., 1995; Robertson et al., 2000b; Snetkov et al., 2003; Sweeney and Yuan, 2000; Wang et al., 2004). Voltage-independent calcium entry is one potentially important mechanism contributing to the increase [Ca2+]i during hypoxia (Robertson et al., 2000b; Snetkov et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004). Store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCC) are activated by depletion of SR Ca2+ stores, which are then replenished by the resulting increase in capacitive calcium entry (CCE) (McDaniel et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004). SOCC involved in CCE are comprised of mammalian homologs of transient receptor potential (TRP) and transient receptor potential-like (TRPL) proteins, which form light-activated cation channels in photoreceptor cells of Drosophila menlanogaster (Wang et al., 2004). Wang et al. demonstrated that transient receptor potential channels (TRPC) are expressed in distal intrapulmonary arteries, a major site of vasomotor responses in the pulmonary circulation (Wang et al., 2004). Distal intrapulmonary arteries express mRNA and protein for TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6 (Wang et al., 2004) supporting the possible involvement of CCE in HPV. The endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ sensor, stromal-interacting molecule (STIM1), may interact with most of the TRPC proteins to regulate their function as a SOCC (Yuan et al., 2007). For example, STIM1 directly regulates TRPC1 and TRPC4 as SOCC through this interaction. By contrast, STIM1 does not directly interact with TRPC6, although STIM1 indirectly regulates agonist-induced TRPC6 activation through its interaction with STIM1-regulated TRPC4. In support of a role for TRPC in the acute phase of HPV, hypoxia-induced DAG was shown to activate membrane-bound TRPC6 channels resulting in Na+ influx, membrane depolarization, and activation of L-type, voltage-gated calcium channels (Weissmann et al., 2006a). Also, the Ca2+ release-activated channel (CRAC), formed from the interaction of STIM1 and Orai channel proteins, is highly selective for Ca2+ and also represents a likely candidate for HPV responses (Hewavitharana et al., 2007). Finally, a role for voltage-dependent calcium entry was suggested by Post et al. who reported that the release of Ca2+ from internal stores caused inhibition of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)-sensitive KV channels (Post et al., 1995). The resulting decrease in K+ current caused membrane depolarization and the opening of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels leading to increased [Ca2+]i. However, when voltage-dependent calcium entry was blocked by the L-type inhibitor nifedipine, the acute phase of the HPV response was only partially attenuated (Robertson et al., 2000b). This suggests that voltage-dependent and voltage-independent calcium entry most likely have a synergistic relationship in the acute phase of HPV.

3. Hypoxia-induced systemic vasodilation

While it is well documented that systemic arteries dilate in response to hypoxia, little work has focused on identifying the O2 sensor responsible for this response. Guyton et al. originally demonstrated that changes in PO2 could elicit changes in vascular resistance in canine hind limb (Guyton et al., 1964). Decreases in oxygen tension in systemic tissues have been shown to decrease [ATP], increase adenosine release, and increase release of lactic acid and potassium, each of which can affect vascular resistance (Furchgott, 1966; Taggart and Wray, 1998). However, studies suggest that hypoxia-induced SASMC relaxation is independent of energy stores and mitochondrial activity (Coburn et al., 1979). Furthermore, hypoxia-induced SA dilation occurs in a PO2 range of 20–100 torr, which should be sufficient to maintain mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (Detar, 1980).

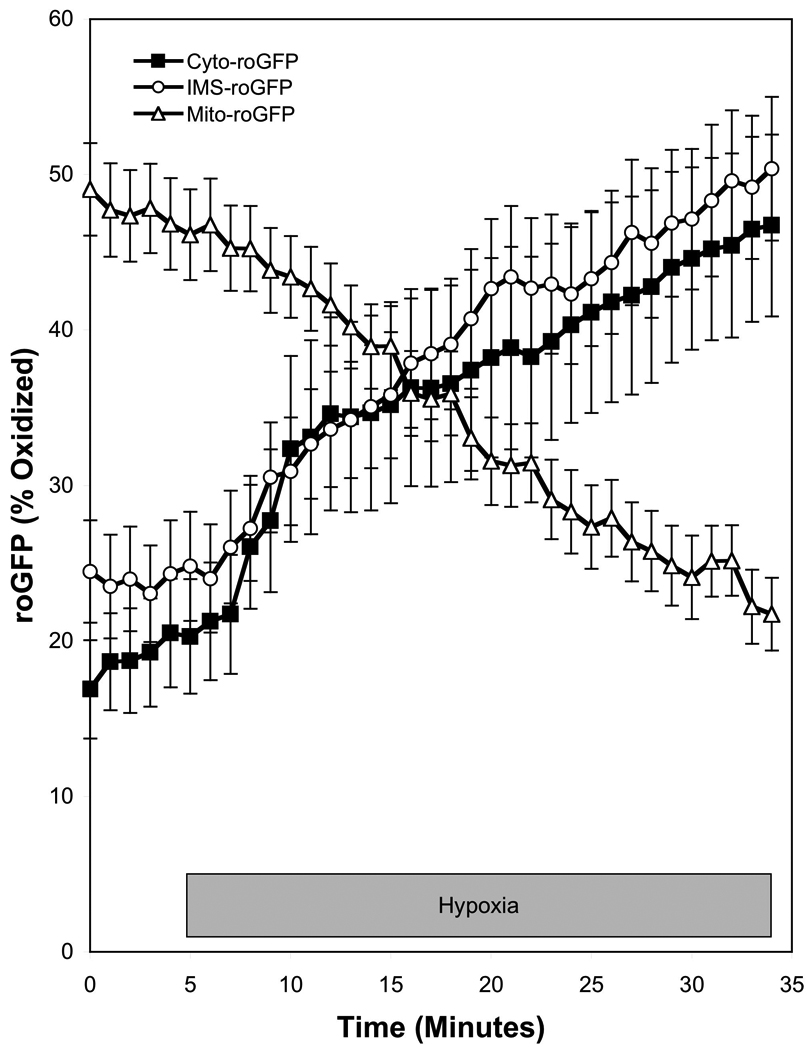

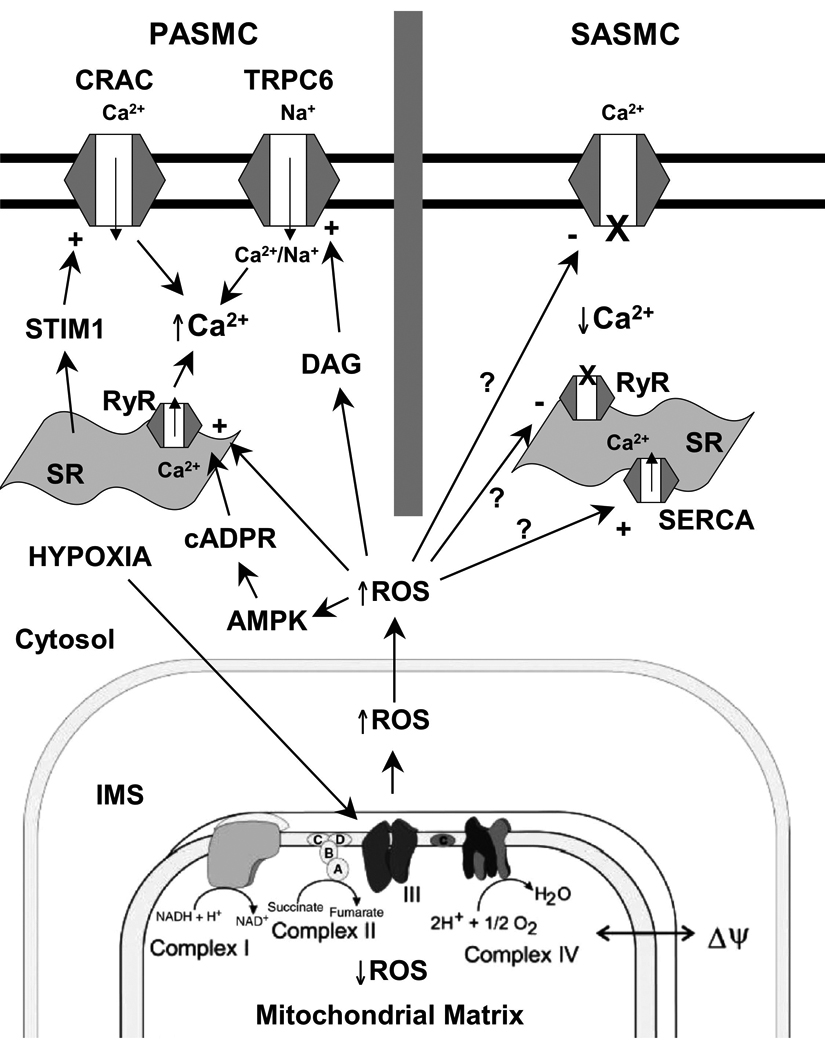

Hypoxia apparently does not inhibit K+ currents in SASMC (Post et al., 1992; Yuan et al., 1993). However, decreases in oxygen tension rapidly inhibit calcium currents through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in SASMC, resulting in a decrease in [Ca2+]i and relaxation (Franco-Obregon et al., 1995; Lopez-Barneo et al., 1999; Saitoh et al., 2006; Smani et al., 2002). Michelakis et al. reported that ROS generation increases during hypoxia in renal PA, as assessed by lucigenin, Amplex Red, and DCF (Michelakis et al., 2002). A similar hypoxia-induced shift in the redox status of SASMC to a more oxidized state was observed by Gupte et al, who measured hypoxia-induced decreases in the [NADPH]/[NADP+] and [GSH]/[GSSG] ratios of bovine coronary arteries (Gupte and Wolin, 2006). It was also reported that hypoxia-induced vasodilation was attenuated by the thiol-reducing agent DTT (3 mM) (Gupte and Wolin, 2006). These disparate redox responses of the PASMC and SASMC to hypoxia lead Michelakis et al. to conclude that tissue-specific differences in mitochondrial function explain the tissue-specific responses to hypoxia (Michelakis et al., 2002). However, Mehta et al. detected decreases in ROS generation in both PASMC and coronary artery smooth muscle cells using DCF, dihydroethidium, and Amplex Red (Mehta et al., 2008). We employed the roGFP sensor to examine ROS signaling in SASMC. When targeted to the IMS or the cytosol, roGFP detected increases in hypoxia-induced ROS signaling in SASMC that were similar to those measured in PASMC (Figure 2) (Waypa et al., 2010). Likewise, hypoxia elicited decreases in matrix oxidation during hypoxia. However, hypoxia triggered increases in [Ca2+]i in PASMC, whereas it elicited decreases in SASMC (Waypa et al., 2010). These findings suggest that PASMC and SASMC share a similar O2 sensor and signaling mechanism, while differences in the downstream signaling pathways lead to opposite functional responses to hypoxia (Figure 3). Possible mechanisms of hypoxia-induced relaxation in SASMC include the inhibition of calcium entry, inhibition of intracellular release, and accelerated uptake by the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump (Gupte and Wolin, 2006).

Figure 2.

Hypoxia increases regulated ROS signaling in the cytosol and IMS of SASMC while decreasing ROS signaling in the mitochondrial matrix. The redox sensor roGFP was targeted to the cytosol (Cyto-roGFP), the IMS (IMS-roGFP), and the mitochondrial matrix (Mito-roGFP) of SASMC, which were then superfused under controlled O2 conditions. Hypoxia (1.5% O2) increased oxidation of roGFP in the cytosol and IMS, and decreased oxidation in the mitochondria matrix. (Data replotted from a previously published report (Waypa et al., 2010)).

Figure 3.

Oxygen sensing model underlying hypoxia-induced responses in pulmonary and systemic vascular cells. PASMC, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell; SASMC, systemic arterial smooth muscle cell; CRAC, Ca2+ release activated channel; TRPC6, transient receptor potential channel-6; STIM1, stromal-interacting molecule-1; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; DAG, diacylglycerol; RyR, ryanodine receptors; cADPR, cyclic ADP ribose; AMPK, AMP kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SERCA, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump; IMS, intermembrane space.

4. Mitochondria and extramitochondrial O2 sensors

A growing body of work indicates that ROS signaling increases during hypoxia in a wide range of cell types, and that this redox response is required for the functional response to hypoxia (Chandel et al., 1998; Duranteau et al., 1998; Gusarova et al., 2009; Guzy et al., 2008; Lavani et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2003; Mansfield et al., 2005; Pastukh et al., 2007; Vanden Hoek et al., 1998; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002). Several pieces of evidence implicate the mitochondria as the site of O2 sensing. Based on measurements in subcellular compartments, it appears that generation of ROS near the outer surface of the inner membrane is responsible for the cytosolic oxidant shift, rather than from the leakage of ROS from the matrix to the cytosol. Genetic knockdown studies indicate that Complex III function is required for the ROS signaling and for the downstream responses (Guzy et al., 2005), however the molecular details of this process are not yet clear. Recently, a naturally occurring small molecule was found to interact with the cellular oxygen sensor in a highly specific manner. The molecule was identified in a large-scale screen of crude extracts collected from a library of microbial species. Initially, a crude extract that strongly inhibited the functional response to hypoxia in human endothelial cells (HUVEC) in vitro was identified from the fungal strain, Embellisia chlamydospora (Jung et al., 2010). Fractionation studies identified the active molecule as a bicyclo sesterterpene, terpestacin. Administration of the purified compound to cultured HUVECs recapitulated the effects of the crude extract on the hypoxic response, and administration to mice attenuated tumor growth and tumor angiogenesis in murine xenograft studies. Using a phage-display analysis, the protein target of the compound was identified as UQCRB, a 13.4 kDa subunit component of Complex III. Consistent with that interaction, studies with the fluorescently labeled compound indicated that terpestacin accumulation in the cell colocalized with mitochondria. Subsequent studies revealed that terpestacin inhibits the hypoxia-induced increase in ROS generation from mitochondria, and that it inhibits the hypoxia-induced stabilization of HIF-1α without abolishing the response to hypoxia mimetic drugs such as deferoximine. Thus, it appears that terpestacin blocks the hypoxic response of cells by binding to Complex III, inhibiting the generation of an ROS signal in hypoxia, and thereby blinding the cell to the presence of hypoxia. This appears to blunt tumor growth by interfering with the hypoxia-induced expression of vascular mitogens through an attenuation of HIF-1 activation. To be sure, the mitochondrial inhibitors stigmatellin and myxothiazol also block the hypoxic ROS signal and HIF-1α stabilization, but they do so by preventing electron entry into Complex III. A consequence of that effect is the inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation by the mitochondria, which produces a bioenergetic crisis in many cells. By contrast, terpestacin appears to inhibit the ability of Complex III to function as an O2 sensor without interfering with the overall electron transport process required for ATP generation below the toxic threshold. In that regard, terpestacin interferes with only one of two biological functions of Complex III. Is UQCRB an oxygen sensor by itself? This possibility seems unlikely, as there is no evidence that this small subunit can interact with molecular O2 in the absence of the remainder of the Complex. More likely, the binding of terpestacin to UQCRB may alter the function of the intact Complex in a manner that interferes with the ability to increase ROS generation from the Qo site near the outer surface of the IMS, thereby abrogating the generation of a signal that activates the cellular response to hypoxia. However, further work is needed to fully understand the relationship between UQCRB and the oxygen sensing function of Complex III. In any case, the discovery of a naturally occurring molecule that specifically targets the oxygen sensing function of Complex III, identified through an unbiased screen of a microbial library, provides strong independent confirmation that Complex III is a critical component of a mitochondrial oxygen sensing system.

ROS production in the mitochondrial matrix can also occur at Complex II, which consists of four polypeptide subunits A-D. Paddenberg et al. suggested the involvement of this Complex in HPV through the reversal of Complex II activity from succinate dehydrogenase to fumarate reductase, thus increasing ROS production during hypoxia (Paddenberg et al., 2003). Finally, ROS do not appear to be generated by Complex IV (Fabian and Palmer, 1998), due to the high-affinity trapping of O2 at the binuclear center (Verkhovsky et al., 1996). Cyanide, which blocks Complex IV, appears to induce smooth muscle contraction during normoxia by causing electrons to backup in Complexes I, II and III, causing those sites to become fully reduced and increasing the generation of superoxide from reduced flavin groups (Archer et al., 1993; Leach et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002).

There is some evidence that hypoxia-induced ROS generation may also originate from non-mitochondrial sources. In that regard it is possible that a NOX system contributes to or amplifies the hypoxia-induced ROS generation, thereby affecting redox conditions in the cytosol and IMS (Weissmann et al., 2006b). While previous research suggests that the mitochondria are the principal source of the hypoxia-induced ROS signal (Chandel et al., 1998; Guzy et al., 2005; Guzy et al., 2007; Leach et al., 2001; Rathore et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2007; Waypa et al., 2001; Waypa et al., 2006; Waypa et al., 2002; Weissmann et al., 2003), Rathore et al. suggested that hypoxia-induced mitochondrial ROS signaling triggers NAD(P)H oxidase activation through PKCε activation (Rathore et al., 2008). This would provide a mechanism by which both mitochondria and cytosolic oxidant systems might contribute to the overall increase in ROS signaling during hypoxia.

5. Concluding remarks

Recent advancements in redox sensors have increased our understanding of how mitochondria, functioning as O2 sensors, can detect a decrease in oxygen tension and translate that into a signal that triggers adaptive responses (Figure 3). The fact that both PASMC and SASMC demonstrate similar changes in hypoxia-induced ROS signaling in various sub-cellular compartments while triggering different downstream responses suggests that the mitochondria may coordinate diverse responses to hypoxia in wide range of cell types. The identification of new small molecules that target the mitochondria and that modify the ROS signaling during hypoxia provides further evidence for the role of Complex III in the oxygen-sensing pathway. Additional progress is needed in the development of genetic tools to moderate and measure ROS signaling, while other studies are needed to identify the downstream targets of ROS signals that mediate their functional responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by HL35440, HL079650 and RR025355 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaronson PI, Robertson TP, Ward JP. Endothelium-derived mediators and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Respir Physiolo Neurobiol. 2002;132:107–120. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MH, Pearlstein DP, Mathieu CE, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial Requirement for Endothelial Responses to Cyclic Strain: Implications for Mechanotransduction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00389.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer S, Michelakis E. The Mechanism(s) of Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction: Potassium Channels, Redox O(2) Sensors, and Controversies. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:131–137. doi: 10.1152/nips.01388.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Huang J, Henry T, Peterson D, Weir EK. A redox-based O2 sensor in rat pulmonary vasculature. Circ Res. 1993;73:1100–1112. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, London B, Hampl V, Wu X, Nsair A, Puttagunta L, Hashimoto K, Waite RE, Michelakis ED. Impairment of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in mice lacking the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.5. Faseb J. 2001;15:1801–1803. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0649fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Reeve HL, Michelakis E, Puttagunta L, Waite R, Nelson DP, Dinauer MC, Weir EK. O2 sensing is preserved in mice lacking the gp91 phox subunit of NADPH oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7944–7949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Souil E, Dinh-Xuan AT, Schremmer B, Mercier JC, El Yaagoubi A, Nguyen-Huu L, Reeve HL, Hampl V. Molecular identification of the role of voltage-gated K+ channels, Kv1.5 and Kv2.1, in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and control of resting membrane potential in rat pulmonary artery myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2319–2330. doi: 10.1172/JCI333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Weir EK, Reeve HL, Michelakis E. Molecular identification of O2 sensors and O2-sensitive potassium channels in the pulmonary circulation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;475:219–240. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46825-5_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Will JA, Weir EK. Redox status in the control of pulmonary vascular tone. Herz. 1986;11:127–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbirz S, Jakob U, Glocker MO. Mass spectrometry unravels disulfide bond formation as the mechanism that activates a molecular chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18759–18766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman SA. Vasoconstrictor effect of endothelin-1 on hypertensive pulmonary arterial smooth muscle involves Rho-kinase and protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L472–L479. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00101.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi I, Bishopric NH, Discher DJ, Wu X, Webster KA. Cell-specificity and signaling pathway of endothelin-1 gene regulation by hypoxia. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;30:975–984. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(95)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher PC, Pearse DB, Pillai RP, Litt MC, Mitchell MC, Sylvester JT. Energy state and vasomotor tone in hypoxic pig lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:1874–1881. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MB, Remington JS. Redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein: probes for dynamic intracellular redox responses. A review. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;476:50–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-129-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha CY, Earm KH, Youm JB, Baek EB, Kim SJ, Earm YE. Electrophysiological modelling of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in the rabbits--special consideration to the generation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11715–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, Schumacker PT. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem. 2000a;275:25130–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Trzyna WC, McClintock DS, Schumacker PT. Role of oxidants in NF-kappa B activation and TNF-alpha gene transcription induced by hypoxia and endotoxin. J Immunol. 2000b;165:1013–1021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi AY, Waypa GB, Mungai PT, Schumacker PT. Prolonged hypoxia increases ROS signaling and RhoA activation in pulmonary artery smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:603–610. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn RF. Oxygen tension sensors in vascular smooth muscle. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1977;78:101–115. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9035-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn RF, Grubb B, Aronson RD. Effect of cyanide on oxygen tension-dependent mechanical tension in rabbit aorta. Circ Res. 1979;44:368–378. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan DB, Jones M, Garcia LM, Noria S, del Nido PJ, McGowan FX., Jr Hypoxia and stretch regulate intercellular communication in vascular smooth muscle cells through reactive oxygen species formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1754–1760. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000093546.10162.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desireddi JR, Farrow KN, Marks JD, Waypa GB, Schumacker PT. Hypoxia increases ROS signaling and cytosolic Ca(2+) in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells of mouse lungs slices. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:595–602. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detar R. Mechanism of physiological hypoxia-induced depression of vascular smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:H761–H769. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.6.H761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipp M, Evans AM. Cyclic ADP-ribose is the primary trigger for hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in the rat lung in situ. Circ Res. 2001;89:77–83. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipp M, Nye PC, Evans AM. Hypoxic release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of pulmonary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L318–L325. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley CT, Dore TM, Hanson GT, Jackson WC, Remington SJ, Tsien RY. Imaging dynamic redox changes in mammalian cells with green fluorescent protein indicators. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22284–22293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranteau J, Chandel NS, Kulisz A, Shao Z, Schumacker PT. Intracellular signaling by reactive oxygen species during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11619–11624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eu JP, Xu L, Stamler JS, Meissner G. Regulation of ryanodine receptors by reactive nitrogen species. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM. The role of intracellular ion channels in regulating cytoplasmic calciumin pulmonary arterial mmooth muscle: which store and where? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:57–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM, Dipp M. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: cyclic adenosine diphosphate-ribose, smooth muscle Ca(2+) stores and the endothelium. Respir Physiolo Neurobiol. 2002;132:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM, Ward JP. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction - invited article. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;648:351–360. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2259-2_40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian M, Palmer G. Hydrogen peroxide is not released following reaction of cyanide with several catalytically important derivatives of cytochrome c oxidase. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01561-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Obregon A, Urena J, Lopez-Barneo J. Oxygen-sensitive calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle and their possible role in hypoxic arterial relaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4715–4719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF. Metabolic factors that influence contractility of vascular smooth muscle. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1966;42:996–1006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ruiz C, Colell A, Mari M, Morales A, Fernandez-Checa JC. Direct effect of ceramide on the mitochondrial electron transport chain leads to generation of reactive oxygen species. Role of mitochondrial glutathione. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11369–11377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert HF. Molecular and cellular aspects of thiol-disulfide exchange. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1990;63:69–172. doi: 10.1002/9780470123096.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Pacheco FR, Caramelo C, Castilla MA, Deudero JJ, Arias J, Yague S, Jimenez S, Bragado R, Alvarez-Arroyo MV. Mechanism of vascular smooth muscle cells activation by hydrogen peroxide: role of phospholipase C gamma. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:392–398. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimminger F, Weissmann N, Spriestersbach R, Becker E, Rosseau S, Seeger W. Effects of NADPH oxidase inhibitors on hypoxic vasoconstriction in buffer-perfused rabbit lungs. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L747–L752. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.5.L747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte SA, Wolin MS. Hypoxia promotes relaxation of bovine coronary arteries through lowering cytosolic NADPH. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2228–H2238. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00615.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte SA, Wolin MS. Oxidant and redox signaling in vascular oxygen sensing: implications for systemic and pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1137–1152. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusarova GA, Dada LA, Kelly AM, Brodie C, Witters LA, Chandel NS, Sznajder JI. Alpha1-AMP-activated protein kinase regulates hypoxia-induced Na,K-ATPase endocytosis via direct phosphorylation of protein kinase C zeta. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3455–3464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00054-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton AC, Carrier O, Jr, Walker JR. Evidence for Tissue Oxygen Demand as the Major Factor Causing Autoregulation. Circ Res. 1964;15 SUPPL:60–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, Simon MC, Hammerling U, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Mack MM, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and gene transcription in yeast. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1317–1328. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Sharma B, Bell E, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT. Loss of the SdhB, but Not the SdhA, subunit of complex II triggers reactive oxygen species-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor activation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:718–731. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GT, Aggeler R, Oglesbee D, Cannon M, Capaldi RA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Investigating mitochondrial redox potential with redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13044–13053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasunuma K, Rodman DM, McMurtry IF. Effects of K+ channel blockers on vascular tone in the perfused rat lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:884–887. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewavitharana T, Deng X, Soboloff J, Gill DL. Role of STIM and Orai proteins in the store-operated calcium signaling pathway. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC, Clark MG, Bloxham DP, Lardy HA. Mechanism of action of the hypoglycemic agent diphenyleneiodonium. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:6050–6056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma N, Nagaoka T, Morio Y, Ota H, Gebb SA, Karoor V, McMurtry IF, Oka M. Endothelin-1 and serotonin are involved in activation of RhoA/Rho kinase signaling in the chronically hypoxic hypertensive rat pulmonary circulation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:697–702. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181593774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Discher DJ, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Hypoxia regulates expression of the endothelin-1 gene through a proximal hypoxia-inducible factor-1 binding site on the antisense strand. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:894–899. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda I, Devedjiev Y, Derewenda U, Dauter Z, Bielnicki J, Cooper DR, Graf PC, Joachimiak A, Jakob U, Derewenda ZS. The crystal structure of the reduced, Zn2+-bound form of the B. subtilis Hsp33 chaperone and its implications for the activation mechanism. Structure (Camb) 2004;12:1901–1907. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K, Schwarzer C, Lally E, Zhang S, Ruzin S, Machen T, Remington SJ, Feldman L. Expression and characterization of a redox-sensing green fluorescent protein (reduction-oxidation-sensitive green fluorescent protein) in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:397–403. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin N, Packer CS, Rhoades RA. Reactive oxygen-mediated contraction in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle: cellular mechanisms. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:383–388. doi: 10.1139/y91-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP, Kennedy FG. Intracellular oxygen supply during hypoxia. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:C247–C253. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.243.5.C247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP, Kennedy FG. Analysis of intracellular oxygenation of isolated adult cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:C384–C390. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.3.C384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RD, Thompson JS, Morice AH. The NADPH oxidase inhibitors iodonium diphenyl and cadmium sulphate inhibit hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in isolated rat pulmonary arteries. Physiol Res. 2000;49:587–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HJ, Shim JS, Lee J, Song YM, Park KC, Choi SH, Kim ND, Yoon JH, Mungai PT, Schumacker PT, Kwon HJ. Terpestacin inhibits tumor angiogenesis by targeting UQCRB of mitochondrial complex III and suppressing hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species production and cellular oxygen sensing. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11584–11595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TM, Park MK, Uhm DY. Characterization of hypoxia-induced [Ca2+]i rise in rabbit pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Life Sci. 2002;70:2321–2333. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01497-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TM, Park MK, Uhm DY. Effects of hypoxia and mitochondrial inhibition on the capacitative calcium entry in rabbit pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Life Sci. 2003;72:1467–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killilea DW, Hester R, Balczon R, Babal P, Gillespie MN. Free radical production in hypoxic pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L408–L412. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.2.L408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Szocs K, Yin Q, Akers M, Zhang Y, Grant SL, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Novel gp91(phox) homologues in vascular smooth muscle cells : nox1 mediates angiotensin II-induced superoxide formation and redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Circ Res. 2001;88:888–894. doi: 10.1161/hh0901.090299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavani R, Chang WT, Anderson T, Shao ZH, Wojcik KR, Li CQ, Pietrowski R, Beiser DG, Idris AH, Hamann KJ, Becker LB, Vanden Hoek TL. Altering CO2 during reperfusion of ischemic cardiomyocytes modifies mitochondrial oxidant injury. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1709–1716. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269209.53450.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazor R, Feihl F, Waeber B, Kucera P, Perret C. Endothelin-1 does not mediate the endothelium-dependent hypoxic contractions of small pulmonary arteries in rats. Chest. 1996;110:189–197. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach RM, Hill HM, Snetkov VA, Robertson TP, Ward JP. Divergent roles of glycolysis and the mitochondrial electron transport chain in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of the rat: identity of the hypoxic sensor. J Physiol London. 2001;536:211–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach RM, Robertson TP, Twort CH, Ward JP. Hypoxic vasoconstriction in rat pulmonary and mesenteric arteries. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L223–L231. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.3.L223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach RM, Sheehan DW, Chacko VP, Sylvester JT. Energy state, pH, and vasomotor tone during hypoxia in precontracted pulmonary and femoral arteries. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L294–L304. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.2.L294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XQ, Zheng YM, Rathore R, Ma J, Takeshima H, Wang YX. Genetic evidence for functional role of ryanodine receptor 1 in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:771–783. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0556-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MJ, Yang XR, Cao YN, Sham JS. Hydrogen peroxide-induced Ca2+ mobilization in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1598–L1608. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00323.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JQ, Sham JS, Shimoda LA, Kuppusamy P, Sylvester JT. Hypoxic constriction and reactive oxygen species in porcine distal pulmonary arteries. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L322–L333. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00337.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Sham JS, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Hypoxic constriction of porcine distal pulmonary arteries: endothelium and endothelin dependence. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L856–L865. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman JR, Remington SJ. Development of a family of redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators for use in relatively oxidizing subcellular environments. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8678–8688. doi: 10.1021/bi800498g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Barneo J, Pardal R, Montoro RJ, Smani T, Garcia-Hirschfeld J, Urena J. K+ and Ca2+ channel activity and cytosolic [Ca2+] in oxygen-sensing tissues. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wang J, Peng G, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Knockdown of Stromal Interaction Molecule 1 Attenuates Store-operated Ca2+ Entry and Ca2+ Responses to Acute Hypoxia in Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00063.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Differences in STIM1 and TRPC expression in proximal and distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle are associated with differences in Ca2+ responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L104–L113. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00058.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majander A, Finel M, Wikstrom M. Diphenyleneiodonium inhibits reduction of iron-sulfur clusters in the mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21037–21042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield KD, Guzy RD, Pan Y, Young RM, Cash TP, Schumacker PT, Simon MC. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-alpha activation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C, Mamary AJ, Verhoeven AJ, Marshall BE. Pulmonary artery NADPH-oxidase is activated in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:633–644. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.5.8918370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SS, Platoshyn O, Wang J, Yu Y, Sweeney M, Krick S, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Capacitative Ca(2+) entry in agonist-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L870–L880. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry IF. Angiotensin is not required for hypoxic constriction in salt solution-perfused rat lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:375–380. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta JP, Campian JL, Guardiola J, Cabrera JA, Weir EK, Eaton JW. Generation of oxidants by hypoxic human pulmonary and coronary smooth-muscle cells. Chest. 2008;133:1410–1414. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelakis ED, Hampl V, Nsair A, Wu X, Harry G, Haromy A, Gurtu R, Archer SL. Diversity in mitochondrial function explains differences in vascular oxygen sensing. Circ Res. 2002;90:1307–1315. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024689.07590.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohazzab KM, Wolin MS. Sites of superoxide anion production detected by lucigenin in calf pulmonary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:L815–L822. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.6.L815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morio Y, McMurtry IF. Ca(2+) release from ryanodine-sensitive store contributes to mechanism of hypoxic vasoconstriction in rat lungs. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:527–534. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2002.92.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olschewski A, Hong Z, Linden BC, Porter VA, Weir EK, Cornfield DN. Contribution of the K(Ca) channel to membrane potential and O2 sensitivity is decreased in an ovine PPHN model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002a;283:L1103–L1109. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00100.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olschewski A, Hong Z, Nelson DP, Weir EK. Graded response of K(+) current, membrane potential, and [Ca(2+)](i) to hypoxia in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002b;283:L1143–L1150. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00104.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olschewski A, Hong Z, Peterson DA, Nelson DP, Porter VA, Weir EK. Opposite effects of redox status on membrane potential, cytosolic calcium, and tone in pulmonary arteries and ductus arteriosus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L15–L22. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00372.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddenberg R, Ishaq B, Goldenberg A, Faulhammer P, Rose F, Weissmann N, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Kummer W. Essential role of complex II of the respiratory chain in hypoxia-induced ROS generation in the pulmonary vasculature. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L710–L719. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00149.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastukh V, Ruchko M, Gorodnya O, Wilson GL, Gillespie MN. Sequence-specific oxidative base modifications in hypoxia-inducible genes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1616–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post JM, Gelband CH, Hume JR. [Ca2+]i inhibition of K+ channels in canine pulmonary artery. Novel mechanism for hypoxia-induced membrane depolarization. Circ Res. 1995;77:131–139. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post JM, Hume JR, Archer SL, Weir EK. Direct role for potassium channel inhibition in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C882–C890. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmahram GE, Snetkov VA, Shaifta Y, Drndarski S, Knock GA, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Constriction of pulmonary artery by peroxide: role of Ca2+ release and PKC. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero M, Colombo SL, Godfrey A, Moncada S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles in the vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5379–5384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601026103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore R, Zheng YM, Niu CF, Liu QH, Korde A, Ho YS, Wang YX. Hypoxia activates NADPH oxidase to increase [ROS]i and [Ca2+]i through the mitochondrial ROS-PKCepsilon signaling axis in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve HL, Michelakis E, Nelson DP, Weir EK, Archer SL. Alterations in a redox oxygen sensing mechanism in chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2249–2256. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve HL, Weir EK, Nelson DP, Peterson DA, Archer SL. Opposing effects of oxidants and antioxidants on K+ channel activity and tone in rat vascular tissue. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:825–834. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig J, Heinemann SH, Wunder F, Lorra C, Parcej DN, Dolly JO, Pongs O. Inactivation properties of voltage-gated K+ channels altered by presence of beta-subunit. Nature. 1994;369:289–294. doi: 10.1038/369289a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades RA, Packer CS, Roepke DA, Jin N, Meiss RA. Reactive oxygen species alter contractile properties of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1990;68:1581–1589. doi: 10.1139/y90-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Gogvadze V, Laffranchi R, Schlapbach R, Schweizer M, Suter M, Walter P, Yaffee M. Oxidants in mitochondria: from physiology to diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1271:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00012-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TP, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Hypoxic vasoconstriction and intracellular Ca2+ in pulmonary arteries: evidence for PKC-independent Ca2+ sensitization. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H301–H307. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TP, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Ca2+-sensitization during sustained hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction is endothelium-dependent. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00422.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TP, Dipp M, Ward JP, Aaronson PI, Evans AM. Inhibition of sustained hypoxic vasoconstriction by Y-27632 in isolated intrapulmonary arteries and perfused lung of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2000a;131:5–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TP, Hague D, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Voltage-independent calcium entry in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of intrapulmonary arteries of the rat. J Physiol London. 2000b;525(Pt 3):669–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TP, Ward JP, Aaronson PI. Hypoxia induces the release of a pulmonary-selective, Ca(2+)-sensitising, vasoconstrictor from the perfused rat lung. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:145–150. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounds S, McMurtry IF. Inhibitors of oxidative ATP production cause transient vasoconstriction and block subsequent pressor responses in rat lungs. Circ Res. 1981;48:393–400. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S, Zhang C, Tune JD, Potter B, Kiyooka T, Rogers PA, Knudson JD, Dick GM, Swafford A, Chilian WM. Hydrogen peroxide: a feed-forward dilator that couples myocardial metabolism to coronary blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2614–2621. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000249408.55796.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvaterra CG, Goldman WF. Acute hypoxia increases cytosolic calcium in cultured pulmonary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L323–L328. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.3.L323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Morio Y, Morris KG, Rodman DM, McMurtry IF. Mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction involves ET(A) receptor-mediated inhibition of K(ATP) channel. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L434–L442. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.3.L434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham JS, Crenshaw BR, Jr, Deng LH, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Effects of hypoxia in porcine pulmonary arterial myocytes: roles of K(V) channel and endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L262–L272. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.2.L262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DW, Giese EC, Gugino SF, Russell JA. Characterization and mechanisms of H2O2-induced contractions of pulmonary arteries. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H1542–H1547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.5.H1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda LA, Luke T, Sylvester JT, Shih HW, Jain A, Swenson ER. Inhibition of hypoxia-induced calcium responses in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle by acetazolamide is independent of carbonic anhydrase inhibition. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1002–L1012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00161.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smani T, Hernandez A, Urena J, Castellano AG, Franco-Obregon A, Ordonez A, Lopez-Barneo J. Reduction of Ca(2+) channel activity by hypoxia in human and porcine coronary myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snetkov VA, Aaronson PI, Ward JP, Knock GA, Robertson TP. Capacitative calcium entry as a pulmonary specific vasoconstrictor mechanism in small muscular arteries of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:97–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer N, Dietrich A, Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Gudermann T, Schulz R, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Weissmann N. Regulation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: basic mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1639–1651. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00013908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic I, Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Lucigenin: redox potential in aqueous media and redox cycling with O-(2) production. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373:447–450. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney M, Yuan JX. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of voltage-gated potassium channels. Respir Res. 2000;1:40–48. doi: 10.1186/rr11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]