Abstract

Background

Primary pneumonic plague is rare among humans but treatment efficacy may be tested in appropriate animal models under the FDA ‘Animal Rule’.

Methods

Ten African Green monkeys (AGM) inhaled 44 to 255 LD50 doses of aerosolized Y. pestis strain CO92. Continuous telemetry, arterial blood gases, chest radiography, blood culture, and clinical pathology monitored disease progression.

Results

Onset of fever, >39°C detected by continuous telemetry, 52 to 80 h post-exposure Was the first sign of systemic disease and provides a distinct signal for treatment initiation. Secondary endpoints of disease severity include tachypnea, measured by telemetry, bacteremia, extent of pneumonia imaged by chest x-ray, and serum lactate dehydrogenase enzyme levels.

Conclusions

Inhaled Y. pestis in the AGM results in a rapidly progressive and uniformly fatal disease with fever and multifocal pneumonia, serving as a rigorous test model for antibiotic efficacy studies.

Keywords: plague, pneumonia, African Green monkey, telemetry

Introduction

Plague, a systemic infection caused by Yersinia pestis, presents as two forms, the more common bubonic plague transmitted from infected mammals through the bite of an infected flea, and the rare highly lethal pneumonic plague, acquired through the inhalation of the pathogen. Bubonic plague has been well-characterized in humans [27], its epidemiology understood in many endemic regions of the world, and the rat model has been described [33].

In contrast, primary pneumonic plague or inhalational plague, is rarely acquired under natural conditions [5, 8, 12, 27, 29, 38] and in most cases occur in outbreaks in the developing world. Little data exists on the progression of disease in humans, and animal models are under development. Recently the murine model of pneumonic plague has been described in detail as a two-phase disease with an anti-inflammatory phase followed abruptly by a pro-inflammatory phase [4, 23]. A number of seminal studies of pneumonic plague in non-human primates were performed more than several decades ago [14, 26, 35, 39]. The advent of radiotelemetry now provides a non-invasive technology to continuously monitor vital signs and identify milestones of disease progression.

The purpose of characterizing non-human primate models of inhalational plague is primarily for pre-clinical evaluation of candidate vaccines and treatments [21]. This is particularly critical since the high virulence and ease of aerosolization make Yersinia pestis a potential aerosolized bioweapon [27]. The FDA ‘Animal Rule’ allows the use of animal models to substitute for human testing if the model mimics human disease and is well characterized. Adequate characterization should include cause of death, phases of disease progression, and definition of secondary endpoints of disease severity in addition to the primary endpoint of reduction in mortality [2, 16, 30]. Secondary endpoints of pneumonic plague may include the duration of the incubation period, rapidity of progression to severe illness, frequency of fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, and bacteremia, shock, thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, and extent of multilobar pneumonia with hypoxemia.

Since treatments for pneumonic or bubonic plague have never been evaluated by randomized trials in humans, antibiotics deemed efficacious have been identified by clinical experience [3, 21]. An aminoglycoside (primarily gentamicin since streptomycin is no longer available) alone or in combination with tetracyclines is the current standard of treatment. Fluoroquinolones possess potent in vitro activity but clinical experience has been too limited to establish clinical efficacy. Therefore, efficacy of fluorquinolones in an appropriate animal model of pneumonic plague was needed.

Selection of an appropriate non-human primate species is an important first step. The inhalation LD50 of Y. pestis strain CO92 has been documented in the highly susceptible cynomolgus macaque [36], but macaques occasionally survive even highly lethal doses [9]. The African Green monkey (AGM) is not an endangered species, is free of herpes virus B, STLV, malaria and other pathogens, and is evolutionarily closer to humans than Asian macaques [13]. AGM are known to be highly susceptible to infection by the aerosol route with Y. pestis [1, 10]and the LD50 has been previously established as 350 colony forming units (CFU) [28].

The present study characterized the progression of disease in ten telemetered AGM exposed to high doses of aerosolized Y. pestis strain CO92. The goals included confirming a dose assuring uniform lethality, identifying a sign of established disease to initiate post-exposure treatment trials and finally characterizing secondary endpoints in the evaluation of treatments.

Methods

Non-human primates

Ten African Green monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops) were wild-caught on St. Kitts island and obtained from the National Institutes of Health and Alpha-Genesis, Inc. Five females and five males weighed 3–6 kg and their ages were unknown. AGM were individually housed in autoclavable 4.3 ft2 stainless steel squeeze cages with wire mesh bottoms. Caging provided water ad libitum and fresh feed was provided twice daily. Animal enrichment was provided based on animal needs and veterinarian recommendation. Animals were screened for and seronegative for Herpes B-virus, Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), Simian Retro Virus (SRV), and Simian T-cell Leukemia virus (STLV). Only monkeys of acceptable health, including negative tuberculosis tests, were used on the study. Animals were conditioned to a restraint collar, poles, restraint chairs, and arm and leg restraints. This conditioning may have been performed once or twice daily, and continued until the monkeys were comfortable and cooperative throughout a given conditioning period. Jackets (Lomir Biomedical, Inc., Malone, NY) were placed on the animals up to 3 days prior to surgical implantation of the Broviac catheter. General procedures for animal care and housing met current AAALAC standards, current standard stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996), and the US Department of Agriculture through the Animal Welfare Act (Public Law 99-198).

Implanted devices

Animals were surgically manipulated to install telemetry monitoring devices, then intravenous Broviac catheters (Bard Access Systems, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT), and after seven days recovery, moved into the ABSL-3 at least 1 week before challenge for acclimation. All animals had T30F telemeters (Integrated Telemetry Systems, Dexter, MI) inserted with training by RMISS, Inc (Wilmington, DE). The telemeter battery pack with integrated temperature sensor was placed in an intramuscular pocket on the left abdominal wall, followed by 2 weeks' observation to permit the wound healing and natural fibrotic reactions to fix the telemeter sensors in place. T30F telemeters provided continuous monitoring of body temperature, intrathoracic pressure, respiratory rate, heart rate, and electrocardiogram. All animals had venous access catheters inserted in the right femoral vein. The catheter was tunneled through the right flank and back, emerging through the skin of the upper mid-back. The exit site and catheter was protected by a jacket as previously described [24]. The catheter was initially maintained with a heparinized (500 U/mL) 5% dextrose in water solution and later switched to lower concentrations of heparin (50 U/mL).

Challenge organism

Yersinia pestis strain CO92 was originally isolated in 1992 from a person with a fatal case of pneumonic plague and was supplied by R. Lyons at the University of New Mexico. All work done was performed under BSL3 conditions. For each cohort exposure, one Working Stock cryovial was removed from frozen storage, thawed, and used to inoculate five Tryptose Blood Agar Base (TBAB) + yeast extract slants. The inoculated slants were incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 72 ± 8 hours. After incubation the slants were washed with 1% peptone, combined and centrifuged at 4100 rpm at 5 ± 3°C for 25 ± 5 minutes. The cell pellet was suspended in 1% peptone and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was determined. The bioaerosol sprays were prepared in Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHIB) from the suspended centrifuged culture based on the OD600 and a previously prepared concentration/OD curve. The suspended culture was adjusted as required to achieve the target aerosol exposure level.

Aerosol exposure

Monkeys were exposed to Y. pestis strain CO92 via head-only inhalation with a target dose of 100 ± 50 ED50 of Y. pestis. One aerosol LD50 in the AGM has been calculated to be 350 CFU [15]. Fasted animals were anesthetized with 4 mg/kg tiletamine-zolazepam (Telazol, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) approximately 15 minutes prior to aerosol exposure. The animal was placed in dorsal recumbency in the plethysmography box, inserting its head through the dental dam head port into the head-only exposure apparatus contained in a Class 3 biosafety cabinet as previously described [5, 9, 17]. The bacteria were nebulized using a Collison nebulizer (MRE-3 jet, BGI, Inc., Waltham, MA) and delivered to the anesthetized monkey which was allowed to breathe freely. Real-time plethysmography (Buxco Electronics, Inc., Sharon, CT) was used to measure tidal, minute and accumulated inhaled volumes during exposure. These data were used to target a total inhaled volume of 5 L for each animal and resulted in exposure times ranging from 10 to 15 minutes. Aerosolized bacteria were sampled from the head exposure box into an all glass impinger (AGI-4; Ace Glass, Inc., Vineland, NJ) and concentrations were confirmed by quantitative bacterial culture. Purity of the aerosolized sample was assessed by colony morphology and growth on Congo Red-containing media. The target particle size, mean mass aerosol diameter (MMAD), of between 1 and 3 μm was determined using a TSI Aerosol Particle Sizer (Model 3321; TSI, Inc, Shoreview, MN). Pathogen dose was calculated using the formula Dose = (C × V), where C was the concentration of viable pathogen in the exposure atmosphere, and V was the total volume inhaled based on Buxco plethysmography and exposure times.

Intravenous infusions

To supplement oral intake and to provide training for a future intravenous antibiotic study, the animals were infused through the Broviac catheter with sterile normal saline at the rate of 0.8–1.2 mL/minute using a calibrated infusion pump (Medex Medfusion 2010, Smiths Medical North America, Dublin, OH) for 20 ± 05 minutes every 11–13 hours, beginning 1 day after aerosol challenge and continuing until euthanasia.

Observations and measurements

Beginning with exposure day twice daily cage-side observations included activity, posture, nasal discharge, sneezing, coughing, respiratory characteristics, ocular discharge, inappetence/anorexia, stool characteristics, seizures, neurologic signs or other abnormalities.

Quantitative bacteriology

Venous blood was drawn from the femoral vein, transferred to a tube containing EDTA, and aliquoted for dilution and plating for quantitative bacteriology. Bacterial load was calculated by plating three dilutions of whole blood or homogenized tissue onto tryptic soy agar (TSA). Following 72 hours of incubation at 28°C, purity was verified on Congo red agar and Y. pestis colonies were enumerated.

Pathology

Whole blood was collected into an EDTA tube and analyzed for blood cell count on an Advia 120 (Bayer Corp., Tarrytown, NY) and into sodium citrate anticoagulant and analyzed on an AMAX Destiny Plus Coagulation Analyzer (Trinity Biotech, Jamestown, NY). Arterial blood was drawn from the tail artery or the femoral artery from unanesthetized restrained animals and immediately analyzed for arterial blood gases (pO2, pCO2 and O2 saturation, and blood lactate and bicarbonate levels) with an iSTAT Analyzer (i-STAT Corporation, Windsor, NJ). When moribund the animal was euthanized with 10 mg ketamine/kg of body weight intramuscularly and 2% isoflurane by mask followed by intravenous euthasol (pentobarbital sodium [86.7 mg/kg] plus phentoin [11.1 mg/kg]). Necropsy was immediately performed upon euthanasia, and tissues were promptly collected and weighed for bacteriologic assays. Lung lobes were gently inflated with neutral buffered formalin to approximate normal volume prior to immersion fixation. Lung was designated as “lung-lesion” sample when collected from a firm discolored region suggesting consolidation. Lung was designated as “lung-nonlesion” sample when collected from an area that appeared normal without discoloration or firmness. Samples of lung for histopathology were taken immediately adjacent to areas sampled for bacteriology to permit parallel analyses. Tissue sections of lung, liver, spleen, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes were paraffin embedded, sectioned at 4–6 μm thick, mounted on standard glass slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopic examination.

Results

Calculated inhaled Y. pestis exposures for each animal resulted in a range of exposures between 44 and 255, with a geometric mean of 118, LD50-equivalent doses; particle sizes averaged 1.38 μm MMAD (mean of each exposure's MMAD) which ranged from 1.16 – 1.72 μm MMAD and had a range of geometric standard deviations from 1.31 μm MMAD to 1.80 μm MMAD. Exposures were performed on two different days with a mean (± standard deviation) of 190 (± 41) LD50-equivalents in the first cohort and 79 (± 33) in the second cohort. However, over the range of doses inhaled there was no correlation between inhaled dose and time to fever or time to moribund euthanasia (Spearman correlation p > 0.01).

Variation in onset of abnormal behaviors was observed; all animals experienced inappetence, postural changes, liquid feces, and decreased activity. Two AGM did not exhibit respiratory distress. Weakness and inability/unwillingness to use the perch was a consistent sign of moribund condition when combined with real-time telemetry observations.

Telemetry monitoring of body temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, and electrocardiogram

Temperature was recorded every minute and averaged for hourly temperatures (examples in Figure 1). Diurnal variation in baseline for each vital sign was obtained for each animal during a four day observation period immediately prior to aerosol exposure. Average pre-exposure temperature minimum at 0200–0400 was 36.5 with a range from 35.1 to 37.3°C. Average pre-exposure temperature maximum between 1400–1800 was 37.5 with ranges from 36.9 to 38.3°C. All animals had a post-exposure temperature maximum of 39°C but this temperature elevation was not sustained in all animals. The average time to first temperature elevation over 39°C (fever definition) was 67 hours (± 11 hours) (Table 1). The interval between onset of fever and time of death or euthanasia (Table 1) ranges from 15 hours to 41 hours, averaging 26 hours.

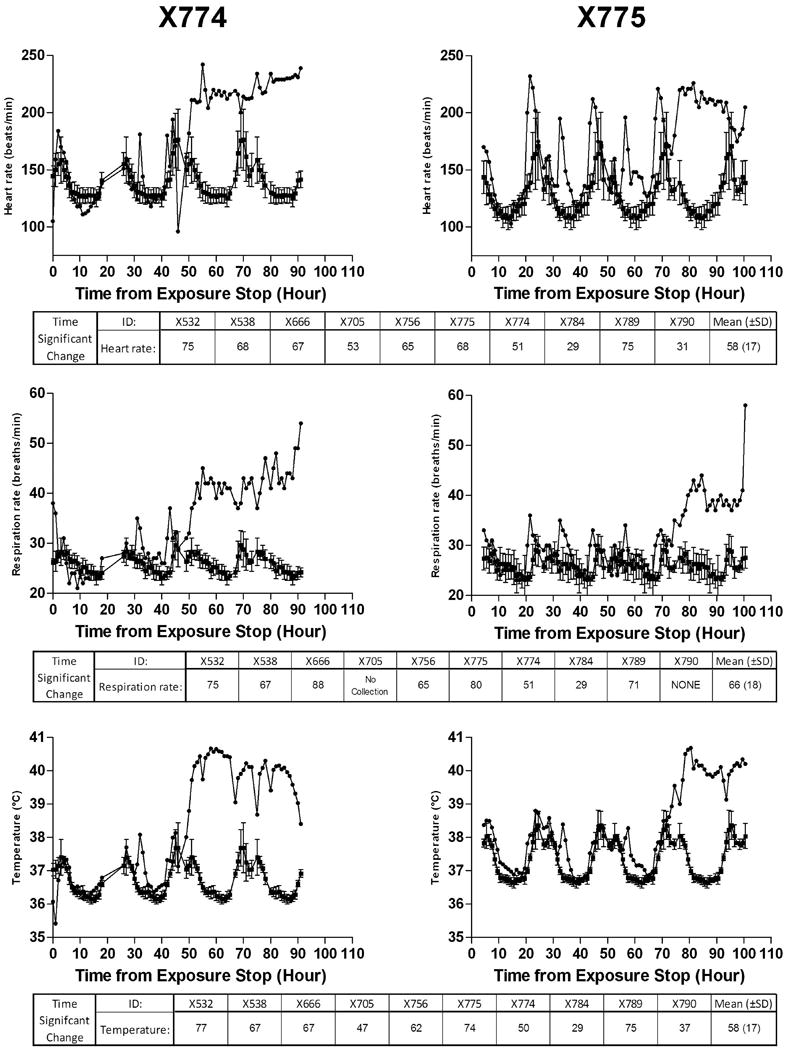

Figure 1.

One-hour averages of heart rate, respiratory rate and body temperature obtained by continuous telemetry in two representative AGMs X774 and X775 infected at time ‘0’. Tables below the illustration for each vital sign describe for all 10 AGM when the measure became significantly different (repeated measures ANOVA) from each animal's baseline. Baseline data with standard deviation are displayed as 24 h repeats on the figure in order to demonstrate how each animal would look at this time PE if not challenged with Y. pestis.

Table 1.

Summary of intervals between aerosol exposure and onset of fever defined by temperature > 39°C and hour of death

| Animal No. | Hours Between Exposure and Temperature >39°C | Hours Between Exposure and Death | Hours Between Fever Onset and Death |

|---|---|---|---|

| X532 | 80 | 95 | 15 |

| X538 | 74 | 93 | 19 |

| X666 | 76 | 96 | 20 |

| X705 | 56 | 86 | 30 |

| X756 | 70 | 95 | 25 |

| X774 | 51 | 72 | 21 |

| X775 | 51 | 92 | 41 |

| X784 | 62 | 100 | 38 |

| X789 | 71 | 99 | 28 |

| X790 | 76 | 102 | 26 |

| Mean (± SD) | 67 (11) | 93 (9) | 26 (8) |

Respiratory rate (RR) was recorded by intrapleural pressure changes and analyzed as inspirations/expirations per minute (middle frames, Figure 1). Elevations in RR above baseline were seen when the animal was chaired for infusions, but the sustained elevations of RR did not occur until the onset of fever (for example, 55 hours post exposure [PE] and 75 hours PE, Figure 1). Some animals displayed marked further increases in tachypnea when moribund (Figure 1), while others slowed their RR, displaying deep respirations with increased intrapleural pressure changes between inspiration and expiration.

Heart rate (HR) was recorded by the analysis software counting R waves per minute. Increased HR was seen with chairing the animal for intravenous infusions every 12 hours, and the magnitude of sustained increased HR at the onset of fever did not exceed that seen during chairing (Figure 1). Moreover, the duration of tachycardia during fever varied among animals and often did not match changes in respiratory rate. Electrocardiogram (ECG) wave forms were recorded as raw data for subsequent review for tachy- or brady-arrhythmias but none were observed in any animal. ECG abnormalities consistently preceded moribund status by approximately 6–12 hours in all animals. The T wave became flattened then inverted, first intermittently then persistently until euthanasia. The ST segment became depressed usually following T wave inversion. These nonspecific signs of myocardial dysfunction often coincided with the appearance of extremely hunched posture, increased negative (inspiratory) and positive (expiratory) intrapleural pressures, and inability to remain perched or inability to climb onto the perch. All of these signs were used to indicate moribund status and need for euthanasia.

Bacteremia post-exposure

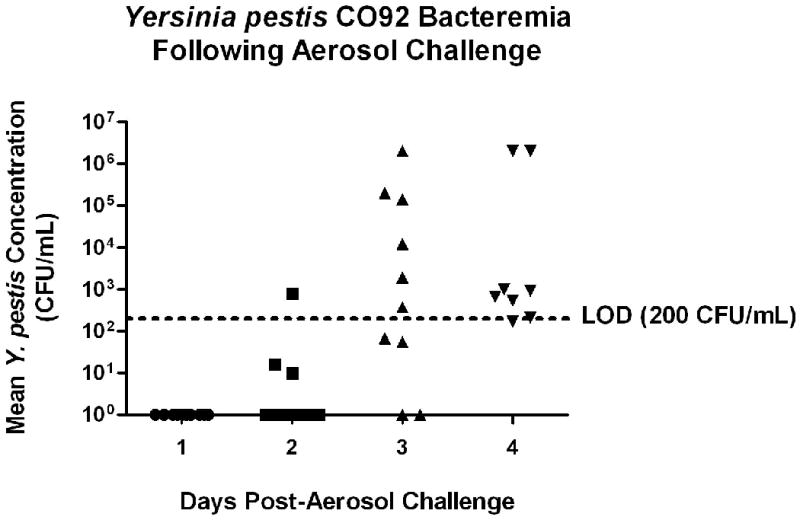

Early (Day 2 PE) positive blood cultures contained low numbers of Y. pestis but subsequent cultures were positive ranging from 200 CFU to >200,000 CFU (Figure 2). There was no relationship between inhaled dose and subsequent onset of or intensity of bacteremia. Detectable bacteremia preceded the onset of fever in seven animals. Since bacteremia was sought only once daily, while body temperature was continuously recorded, bacteremia may have preceded fever in all cases. All tissues sampled demonstrated high pathogen loads (Figure 3), greater than 106 CFU/g tissue in all samples, except liver and spleen in one animal, and non-lesion lung in another animal.

Figure 2.

Y. pestis bacteremia following aerosol challenge in AGM. Collected blood was serially diluted and cultured daily each morning onto TSA for upwards of 4 days post-challenge. Data represent the geometric mean CFU/mL of blood based on the dilution factor and colony counts. The limit of detection (LOD) for this assay was defined as 200 CFU/mL of blood (20 CFU per 100 μL plate inoculum). As shown, certain data points fell below this limit, but were still reported due to the presence of countable Y. pestis colonies.

Figure 3.

Y. pestis tissue burden in moribund AGM following aerosol challenge. Select tissue samples were collected at necropsy, homogenized, serially diluted, and cultured onto TSA. Data represent the geometric mean CFU/g of tissue for all study animals on the dilution factor, colony counts and sample weights. TBLN, tracheobronchial lymph node; NL, non-lesioned sample; L, lesioned sample.

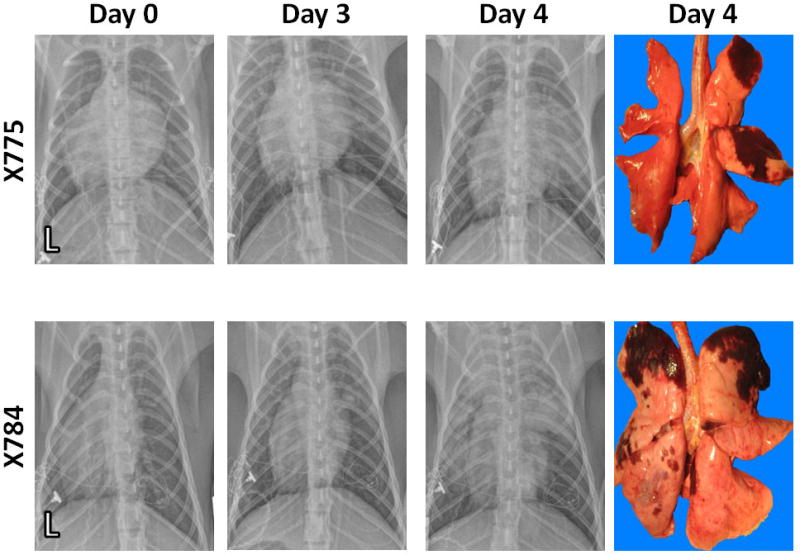

Radiological imaging

All pre-exposure images in these wild-caught AGM showed clear lung fields with one exception (Table 2). On Study Day 3 approximately 72 hours PE single small opacities were visualized in six of nine animals (Figure 4). On the 4th day PE all infiltrates were larger, and multiple new opacities were seen in all but two animals. One animal never developed radiologically detectable infiltrates. Three animals found dead in the cage on the 4th study day had diffuse opacities in all lung fields, probably representing post-mortem capillary leakage. No chest x-ray demonstrated pleural effusion, and no large effusions were found at necropsy. Although imaging was performed only once daily, x-ray abnormalities were detected only after other physiological markers of illness such as fever and increased respiratory rate were established. Examples of the spatial correlation of chest infiltrates and appearance of the lung at moribund necropsy is shown in Figure 4 for two AGM. Most large infiltrates visualized radiologically were seen as corresponding dark hemorrhagic, palpably firm lobes at necropsy (Figure 4, right-hand photographs). However, one large hemorrhagic indurated right cranial lobe (X775), and numerous small foci of hemorrhage, were not visualized by chest x-ray.

Table 2.

Summary of radiological findings

| Animal No. | Study Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 4 | |

| X532 | Clear | Clear | Small left caudal infiltrate |

| X538 | Clear | Small infiltrate right proximal and caudal | Large right caudal and left cranial infiltrate |

| X666 | Small right caudal shadow | Small right caudal shadow | Small right caudal shadow - no infiltrate |

| X705 | Clear | Infiltrate left middle | Found dead - whiteout |

| X756 | Clear | Small left cranial | Large left cranial and middle |

| X774 | Clear | Clear | Diffuse infiltrate every lobe |

| X775 | Clear | Small infiltrate right middle | Large right middle and caudal |

| X784 | Clear | Small right middle | Infiltrates in every lobe except right caudal |

| X789 | Clear | Clear | Whiteout (30 minutes post death) |

| X790 | Clear | Found dead - whiteout | ND |

Figure 4.

Radiological Images of the Chest. Serial chest radiographs from two AGMs obtained prior to exposure (day 0), day 3 PE (approximately 72 h PE), and at the time of moribund necropsy approximately 96 h PE are shown. ‘L’ designates left chest with pleural pressure transducer visible on the left side. AGM X775 displays a clear pulmonary parenchyma on day 0, small periohilar infiltrates in the right middle and right caudal lobes on day 3 PE, and large right middle lobe infiltrate and small right caudal infiltrate at moribund necropsy. AGM X784 displays clear pulmonary parenchyma on day 0, small right cranial and left cranial infiltrates on day 3 PE, and large left cranial, right cranial, left middle, right middle, and right caudal lobe infiltrates at moribund necropsy.

Clinical pathology

The pre-exposure hematological cell counts for total white cells, neutrophils, hemoglobin, hematocrit and red cell indices were within reported normal limits for AGM, but platelet counts for our AGM (Table 3) were approximately half of reported normal limits [18, 32]. The mean peripheral blood white cell count increased to greater than 25,000 cells/mm3, primarily in the neutrophil fraction, ranging on day 4 PE from 66,420 to 2,870 cells/mm3 (Table 3). There was a non-significant (P > 0.05, ANOVA for repeated measures) trend for decreasing hemoglobin, hematocrit and the platelet count over the course of infection (Table 3). Abnormalities in serum chemistry were restricted to serum enzymes. Levels of lactate dehydrogenase were markedly elevated in nine of ten animals (Table 3). Levels of AST but not ALT were modestly elevated without statistical significance. Serum BUN and creatinine levels were not elevated. A trend to prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and elevated fibrinogen (Table 3) are consistent with generalized activation of inflammation. Markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation (elevated D-dimer, prolonged prothrombin time and decreased fibrinogen concentration) were not found. Arterial oxygen saturation and partial pressure was maintained at normal levels until hours prior to moribund euthanasia when mild respiratory alkalosis in two AGM and significant hypoxemia in four AGM was detected (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of clinical pathology for 10 AGM before and after inhalation exposure

| Cell Element | Day -7 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 10.68 (4.34)1 | 9.60 (3.65) | 10.56 (3.39) | 17.50 (10.45) | 23.65 (21.07) |

| Hemoglobin | 14.80 (1.81) | 15.04 (1.38) | 14.55 (1.23) | 14.16 (1.61) | 13.44 (1.86) |

| Hematocrit | 45.95 (4.66) | 45.85 (3.37) | 43.80 (2.97) | 42.37 (4.80) | 40.56 (5.28) |

| Abs. neutrophil count | 4.12 (3.77) | 2.84 (2.08) | 2.39 (1.05) | 10.62 (7.50) | 15.71 (13.37) |

| Platelets | 457 (115) | 473 (107) | 447 (107) | 390 (143) | 369 (183) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 16.9 (4.6) | 22.1 (6.8) | 14.4 (3.7) | 16.4 (10.9) | 18.4 (13.8) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.4) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 89.9 (45.9) | 83.7 (53.6) | 101.0 (44.0) | 104.2 (38.1) | 111.4 (50.4) |

| AST (IU/L) | 41.5 (10.8) | 53.0 (16.2) | 104.9 (49.7) | 166.2 (154.6) | 139.8 (124.0) |

| LDH (IU/L) | 263.4 (60.8) | 354.0 (45.4) | 732.4 (329.2) | 1206.1 (967.6) | 2076.0(2515.5) |

| Prothromb time (sec) | 17.2 (3.8) | 15.7 (0.8) | 16.6 (0.9) | 18.7 (3.9) | 17.0 (1.6) |

| aPTT (sec) | 35.8 (6.9) | 35.2 (10.4) | 43.3 (16.9) | 44.4 (11.4) | 46.8 (6.1)2 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 289 (48) | 278 (46) | 322 (83) | 293 (84) | 526 (157)3 |

| D-Dimer (ng/mL) | 26.0 (11.1) | 19.2 (5.6) | 23.6 (3.2) | 19.9 (5.5) | 26.7 (14.8) |

| Arterial pH | 7.41 (0.06) | 7.38 (0.07) | 7.47 (0.04) | 7.48 (0.06) | 7.46 (0.12) |

| Arterial pO2 (mmHg) | 61.0 (4.2) | 64.2 (8.0) | 63.6 (8.4) | 61.6 (12.4) | 47.8 (11.8)4 |

| Arterial O2 sat (%) | 91.5 (1.7) | 91.5 (3.5) | 92.6 (3.8) | 91.0 (9.1) | 81.7 (15.8) |

Mean (± SD).

Trend to significance from baseline by ANOVA of multiple measures, P = 0.057.

Significant by one-way ANOVA at P < 0.001.

Day 4 significantly different from Day 1 by one-way ANOVA at P = 0.035.

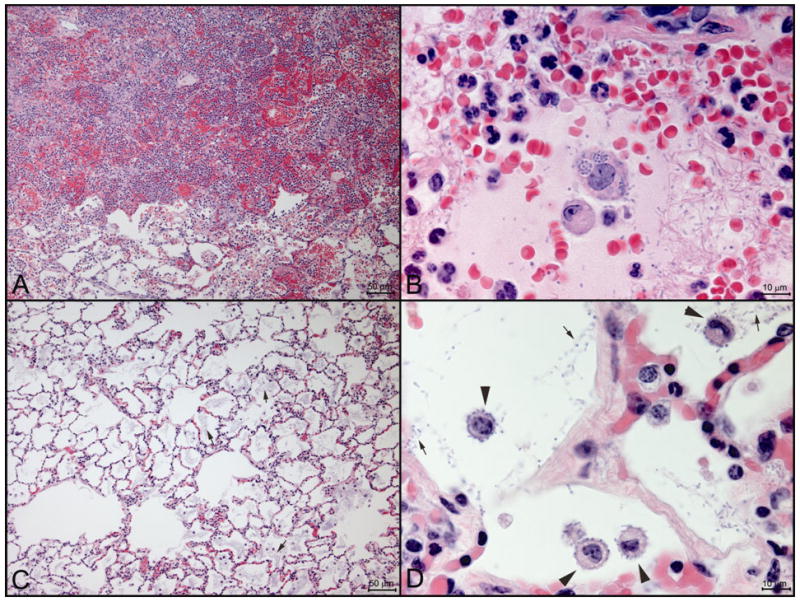

Gross observation revealed the lung tissue to be involved with consolidation, hemorrhage or both ranging from 20% to 60% of the total lung tissue. Lung tissue pieces were selected at necropsy to represent an area of ‘lesion’ or consolidation (firmness and discoloration), and an area of ‘non-lesion’ which appeared grossly normal. Microscopically, lesion lung demonstrated fibrinosuppurative pneumonia and alveolar edema, often with numerous bacteria (Figure 5). Infiltrates in areas of alveolar inflammation/pneumonia were composed primarily of septal and alveolar neutrophils and macrophages, often within a background of eosinophilic, granular protein demonstrative of pulmonary edema. Areas of necrosis were present within severe foci of pneumonia, and extension to surrounding compartments (airways, vasculature) were present.

Figure 5.

Representative pulmonary histopathology of primary pneumonic Y. pestis infection. A) Low power view of fulminant fibrinosuppurative and hemorrhagic pneumonia in a nodular lesion in an AGM (X784) moribund 4 days post-exposure [bar = 100 μm]. B) High power view from same area as A. Abundant extracellular basophilic small rod-like bacteria are present (small arrows). Macrophages within an edema protein-filled alveolus contain numerous intracellular bacteria (arrowhead) [bar = 10 μm]. C) Low power view from a region of the lung without gross lesions from an AGM (X774) moribund 4 days post-exposure. There is prominent hypercellularity of alveolar septae but no substantive exudates. Bluish, granular material within alveoli is composed of abundant extracellular bacteria [bar = 100 μm]. D) High power view from same region as panel C. Bacteria associated with cell surface of alveolar macrophages (arrowheads) as well as extracellular bacteria (small arrows) [bar = 10 μm].

In contrast, the lung-nonlesion areas often displayed septal infiltration with neutrophils and mononuclear cells. In many areas, abundant bacteria were present free within airspaces. At the time of euthanasia with advanced fatal infection, even some areas of grossly normal-appearing lung tissue contained concentrations of Y. pestis approaching that of the consolidated pneumonic areas (Figure 3).

Liver was microscopically relatively unremarkable, with mild to moderate sinusoidal leukocytosis (presence of an increased number of white blood cells within the hepatic sinusoids). In most cases the leukocytes were primarily neutrophils, with lesser numbers of monocytes and lymphocytes. Spleen demonstrated a similar sinusoidal leukocytosis as the principal change; frank splenitis was not a finding in this study. Scattered to moderate numbers of bacteria were occasionally evident within monocytes/macrophages in the spleen. The leukocytosis in the liver and spleen reflects to some extent the systemic increase in circulating white blood cells in response to disease. The tracheobronchial lymph nodes (adjacent to the tracheal bifurcation/carina) displayed a sinusoidal leukocytosis characterized principally by macrophages. Bacteria were often relatively frequent within the cytoplasm of monocytes/macrophages in this draining lymph node and in some cases regions of lymphoid tissue were effaced by bacteria. These tissues did not typically have focal inflammatory nodules or necrosis grossly or within areas examined histologically.

Discussion

We confirmed the 100% lethality of the approximately 100 LD50 dose of aerosolized Y. pestis strain CO92 in African Green monkeys. The challenge dose of 100 LD50 is commonly used in antibiotic and vaccine studies [1, 6, 25, 28]. The number of bacilli inhaled into the lung to establish pulmonary disease is not known in this study. Particle size was important to determine relative distribution into the lung [11, 31]. The targeted MMAD of 1 to 3 μm was achieved, and based on our previous study [7], approximately 10% of the bacteria were deposited in the lung compared with 40% in the nasal-pharyngeal-laryngeal region.

This aerosol dose range of Y. pestis CO92, varying from 44 LD50 to 255 LD50 doses resulted in euthanasia for moribund condition 71 to 102 hours after exposure. Within the limits of interpretation from small numbers, there was no apparent differences in disease and no correlation between exposure dose and length of time to fever, bacteremia, and to euthanasia. Therefore, the challenge levels produced a model of uniform lethal primary pneumonic plague. Cynomolgus macaques infected by the aerosol route in the same dose range of strain CO92 occasionally survive supralethal doses for unknown reasons [9]. Uniform mortality after exposure to 100 LD50 aerosol doses among AGMs may therefore allow smaller group sizes in therapy efficacy studies.

Continuous telemetry of body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate avoids the biases of anesthesia and restraint, and demonstrated the coincident onset of fever and elevated respiratory rate in all AGMs by 72 hours after aerosol exposure. Counting respiratory rate by observation is difficult and often not accurate in non-human primates [36]. Telemeters with an intrapleural pressure transducer allowed accurate respiratory rates and permitted the correlation of the onset of tachypnea with the onset of fever. Heart rate was too sensitive to human activity in the room to serve as a reliable indicator of abnormal physiological stress. Real-time monitoring of telemetered data permitted appropriate timing for euthanasia in order to lessen suffering of the animals, as indicated by falling body temperature less than 34°C, appearance of repolarization abnormalities on the electrocardiogram, and respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths per minute.

The onset of fever defined by temperature greater than 39°C was identified real-time by the continuous telemetry, ranging from 52 hours to 80 hours after aerosol exposure, and occurring 17 to 40 hours prior to death (Table 1). The onset of temperature elevation as departure from baseline was also clearly seen when continuous temperature recordings were compared to daily diurnal variation of that animal (Figure 1). This approach found temperature elevations earlier than the 39°C threshold, as early as 29 h PE (bottom, Figure 1), but this analysis can only be done retrospectively. Thus the threshold fever of 39°C was distinct in every animal, is readily determined realtime, and can serve as the primary signal to initiate post-exposure therapy.

Bacteremia with Y. pestis was sought once daily and first detected 2 to 4 days after aerosol exposure in seven of ten animals and frequently preceded the onset of fever. Detection of bacteremia was limited by the small amount of blood collected and can be improved by Y. pestis rRNA-specific RT-PCR [22]. In CM infected by the same aerosol doses, the onset of bacteremia was detected by culture or RT-PCR only after the onset of fever, and the quantitative bacteremia did not exceed several hundred CFU/mL. Thus the higher levels of bacteremia in AGM (Figure 2) and delayed onset on fever relative to bacteremia may indicate differences in innate defenses between AGM and CM and may contribute to the differences in vaccination success between these two species [34].

The cause of death certainly included severe respiratory failure, but the contribution of sepsis and myocardial failure remain unclear. The appearance of radiographic lung infiltrates on Day 3 indicates well-established pneumonia. However, there was no associated hypoxemia. The patchy nature of pulmonary consolidation appeared to allow compensation by tachypnea for focal arterio-venous shunting until less than 24 hours before death. Myocardial dysfunction was detected by transthoracic echocardiography in some animals by Day 3 and may have contributed to death (Layton and Koster, unpublished data). Blood volume was not directly assessed, although normal serum electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and lack of hemoconcentration was consistent with a minimal loss of circulating blood volume.

The advantages of indwelling catheters, line patency maintained by heparin locks, and restraint using jackets have been previously demonstrated [15, 24]. Phlebotomy under anesthesia as well as stressful restraint may alter hematologic and serum biochemical values [19, 37] but our aseline values matched those previously reported [18, 32]. The one exception was the pre-exposure baseline platelet counts which were approximately half the levels reported previously [18], although the reported levels were obtained during ketamine anesthesia.

We found no abnormalities in four coagulation assays or in the platelet count (Table 3), indicating that disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) did not develop. Coagulopathy and DIC are commonly seen in human septicemic plague [27]. Neither cough nor hemoptysis, a common and helpful diagnostic sign in human pneumonic plague [21, 38], were observed in our AGM. Thus the absence of coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia in AGM may have contributed to the absence of hemoptysis.

The tissue burden of Y. pestis at necropsy was high, particularly in the lung, but also in the tracheobronchial lymph nodes, liver, and spleen [10, 17]. Severe inflammatory alveolitis with fibrinous exudate and hemorrhage in consolidated lesions likely represented the initial foci due to inhalation and the milder alveolitis and edema in ‘non-lesion’ lung tissue was secondary to the bacteremia (Figs. 5). The histopathology at necropsy and the observed course of disease in AGM are consistent with the two phase evolution of primary pneumonic plague in the mouse model [4, 23]. The initial anti-inflammatory phase is characterized by the absence of fever and systemic signs of illness and is mediated by immunosuppressive properties of the Yop proteins [20, 23]. The proinflammatory phase onset is abrupt with fever and respiratory distress representing the progression of focal pneumonia to diffuse alveolitis resulting from the bacteremia [23].

In conclusion, the African green monkey is a suitable model for the evaluation of therapeutic interventions for primary pneumonic plague because there are reasonably consistent intervals between signs of disease and death. The best sign to initiate treatment is body temperature greater than 39° C identified by continuous telemetry. Reliable secondary endpoints of the severity of progressive disease include tachypnea detected by continuous telemetry, bacteremia, serum lactate dehydrogenase enzyme levels, and pulmonary infiltrates by chest x-ray.

Acknowledgments

The project was funded by NIAID contract N01-AI-400095I. We appreciate the round-the-clock assistance of the ABSL3 veterinary technician pool and animal care team; veterinarian surgeons Jose Bayardo, Denise O'Donnell, and Warren Wilson of LRRI, and Steve Pettinger (RMISS, Inc.) for telemeter insertions; Eric Speegle for telemetry software management; Celia Burnett for clinical pathology; and Penny Armijo for necropsy. We thank Kristin DeBord (NIAID) for close collaboration in protocol development. No conflicts of interest exist for any authors.

References

- 1.Andrews GP, Heath DG, Anderson GW, Jr, Welkos SL, Friedlander AM. Fraction 1 Capsular Antigen (F1) Purification from Yersinia Pestis Co92 and from an Escherichia Coli Recombinant Strain and Efficacy against Lethal Plague Challenge. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2180–2187. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2180-2187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boles JW, Pitt ML, LeClaire RD, Gibbs PH, Ulrich RG, Bavari S. Correlation of Body Temperature with Protection against Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B Exposure and Use in Determining Vaccine Dose-Schedule. Vaccine. 2003;21:2791–2796. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulanger LL, Ettestad P, Fogarty JD, Dennis DT, Romig D, Mertz G. Gentamicin and Tetracyclines for the Treatment of Human Plague: Review of 75 Cases in New Mexico, 1985-1999. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:663–669. doi: 10.1086/381545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bubeck SS, Cantwell AM, Dube PH. Delayed Inflammatory Response to Primary Pneumonic Plague Occurs in Both Outbred and Inbred Mice. Infect Immun. 2007;75:697–705. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00403-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burmeister RW, Tigertt WD, Overholt EL. Laboratory-Acquired Pneumonic Plague. Report of a Case and Review of Previous Cases. Ann Intern Med. 1962;56:789–800. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-56-5-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne WR, Welkos SL, Pitt ML, Davis KJ, Brueckner RP, Ezzell JW, Nelson GO, Vaccaro JR, Battersby LC, Friedlander AM. Antibiotic Treatment of Experimental Pneumonic Plague in Mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:675–681. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng YS, Irshad H, Kuehl P, Holmes TD, Sherwood R, Hobbs CH. Lung Deposition of Droplet Aerosols in Monkeys. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:1029–1036. doi: 10.1080/08958370802105413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen RJ, Stockard JL. Pneumonic Plague in an Untreated Plague-Vaccinated Individual. JAMA. 1967;202:365–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelius CA, Quenee LE, Overheim KA, Koster F, Brasel TL, Elli D, Ciletti NA, Schneewind O. Immunization with Recombinant V10 Protects Cynomolgus Macaques from Lethal Pneumonic Plague. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5588–5597. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00699-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis KJ, Fritz DL, Pitt ML, Welkos SL, Worsham PL, Friedlander AM. Pathology of Experimental Pneumonic Plague Produced by Fraction 1-Positive and Fraction 1-Negative Yersinia Pestis in African Green Monkeys (Cercopithecus Aethiops) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day WC, Berendt RF. Experimental Tularemia in Macaca Mulatta: Relationship of Aerosol Particle Size to the Infectivity of Airborne Pasteurella Tularensis. Infect Immun. 1972;5:77–82. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.1.77-82.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doll JM, Zeitz PS, Ettestad P, Bucholtz AL, Davis T, Gage K. Cat-Transmitted Fatal Pneumonic Plague in a Person Who Traveled from Colorado to Arizona. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:109–114. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ervin F, Palmour R. International Perspectives: The Future of Nonhuman Primate Resouces. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. Primates for 21st Century Biomedicine: The St Kitts Vervet (Chlorocebus Aethiops, Sk) pp. 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finegold MJ, Petery JJ, Berendt RF, Adams HR. Studies on the Pathogenesis of Plague. Blood Coagulation and Tissue Responses of Macaca Mulatta Following Exposure to Aerosols of Pasteurella Pestis. Am J Pathol. 1968;53:99–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamble C, Jacobsen K, Leffel E, Pitt M. Use of a Low-Concentration Heparin Solution to Extend the Life of Central Venous Catheters in African Green Monkeys (Chlorocebus Aethiops) JAALAS. 2007;46:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn A, Roy CJ, Powell BS, Adamovicz JJ, Freytag LC, Clements JD. Protection against Aerosolized Yersinia Pestis Challenge Following Homologous and Heterologous Prime-Boost with Recombinant Plague Antigens. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5256–5261. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.5256-5261.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Greer PW, Gabastou JM, Chu M, Hayes E, Nolte KB, Zaki SR. Immunohistochemical Detection of Yersinia Pestis in Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:205–209. doi: 10.1309/HXMF-LDJB-HX1N-H60T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hambleton P, Harris-Smith PW, Baskerville A, Bailey NE, Pavey KJ. Normal Values for Some Whole Blood and Serum Components of Grivet Monkeys (Cercopithecus Aethiops) Lab Anim. 1979;13:87–91. doi: 10.1258/002367779780943585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassimoto M, Harada T, Harada T. Changes in Hematology, Biochemical Values, and Restraint Ecg of Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca Mulatta) Following 6-Month Laboratory Acclimation. J Med Primatol. 2004;33:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang XZ, Nikolich MP, Lindler LE. Current Trends in Plague Research: From Genomics to Virulence. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:189–199. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inglesby TV, Dennis DT, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Friedlander AM, Hauer J, Koerner JF, Layton M, McDade J, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Schoch-Spana M, Tonat K. Plague as a Biological Weapon: Medical and Public Health Management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. Jama. 2000;283:2281–2290. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koster F, Perlin DS, Park S, Brasel T, Gigliotti A, Barr E, Myers L, Layton RC, Sherwood R, Lyons CR. Milestones in Progression of Primary Pneumonic Plague in Cynomolgus Macaques. IAI.01296-01209. 2010 doi: 10.1128/IAI.01296-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lathem WW, Crosby SD, Miller VL, Goldman WE. Progression of Primary Pneumonic Plague: A Mouse Model of Infection, Pathology, and Bacterial Transcriptional Activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17786–17791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506840102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNamee GA, Jr, Wannemacher RW, Jr, Dinterman RE, Rozmiarek H, Montrey RD. A Surgical Procedure and Tethering System for Chronic Blood Sampling, Infusion, and Temperature Monitoring in Caged Nonhuman Primates. Lab Anim Sci. 1984;34:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mett V, Lyons J, Musiychuk K, Chichester JA, Brasil T, Couch R, Sherwood R, Palmer GA, Streatfield SJ, Yusibov V. A Plant-Produced Plague Vaccine Candidate Confers Protection to Monkeys. Vaccine. 2007;25:3014–3017. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer KF, Smith G, Foster L, Brookman M, Sung M. Live, Attenuated Yersinia Pestis Vaccine: Virulent in Nonhuman Primates, Harmless to Guinea Pigs. J Infect Dis. 1974;129 Suppl:S85–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.supplement_1.s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia Pestis--Etiologic Agent of Plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:35–66. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitt M, Dyer D, Leffel E. 46th ICAAC. ASM; 2006. Abstract B-576, Ciprofloxacin Treatment for Established Pneumonic Plaue in the African Green Monkey. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratsitorahina M, Chanteau S, Rahalison L, Ratsifasoamanana L, Boisier P. Epidemiological and Diagnostic Aspects of the Outbreak of Pneumonic Plague in Madagascar. Lancet. 2000;355:111–113. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi CA, Ulrich M, Norris S, Reed DS, Pitt LM, Leffel EK. Identification of a Surrogate Marker for Infection in the African Green Monkey Model of Inhalation Anthrax. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5790–5801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00520-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy CJ, Hale M, Hartings JM, Pitt L, Duniho S. Impact of Inhalation Exposure Modality and Particle Size on the Respiratory Deposition of Ricin in Balb/C Mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2003;15:619–638. doi: 10.1080/08958370390205092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato A, Fairbanks LA, Lawson T, Lawson GW. Effects of Age and Sex on Hematologic and Serum Biochemical Values of Vervet Monkeys (Chlorocebus Aethiops Sabaeus) Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2005;44:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebbane F, Gardner D, Long D, Gowen BB, Hinnebusch BJ. Kinetics of Disease Progression and Host Response in a Rat Model of Bubonic Plague. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1427–1439. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smiley ST. Current Challenges in the Development of Vaccines for Pneumonic Plague. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:209–221. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Speck RS, Wolochow H. Studies on the Experimental Epidemiology of Respiratory Infections. Viii. Experimental Pneumonic Plague in Macacus Rhesus. J Infect Dis. 1957;100:58–69. doi: 10.1093/infdis/100.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Andel R, Sherwood R, Gennings C, Lyons CR, Hutt J, Gigliotti A, Barr E. Clinical and Pathologic Features of Cynomolgus Macaques (Macaca Fascicularis) Infected with Aerosolized Yersinia Pestis. Comp Med. 2008;58:68–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall HS, Worthman C, Else JG. Effects of Ketamine Anaesthesia, Stress and Repeated Bleeding on the Haematology of Vervet Monkeys. Lab Anim. 1985;19:138–144. doi: 10.1258/002367785780942633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Werner SB, Weidmer CE, Nelson BC, Nygaard GS, Goethals RM, Poland JD. Primary Plague Pneumonia Contracted from a Domestic Cat at South Lake Tahoe, Calif. Jama. 1984;251:929–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolochow H, Chatigny M, Speck RS. Studies on the Experimental Epidemiology of Respiratory Infections. Vii. Apparatus for the Exposure of Monkeys to Infectious Aerosols. J Infect Dis. 1957;100:48–57. doi: 10.1093/infdis/100.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]