Abstract

This research examined how Chinese children make moral judgments about lie telling and truth telling when facing a “white lie” or “politeness” dilemma, in which telling a blunt truth is likely to hurt the feelings of another. We examined the possibility that the judgments of participants (age 7 to 11years; total N = 240) would differ as a function of the social context in which communication takes place. The expected social consequences were manipulated systematically in two studies. In Study 1, participants rated truth telling more negatively and lie telling more positively in a public situation, in which a blunt truth is especially likely to have negative social consequences. In Study 2, participants rated truth telling more positively and lie telling more negatively in a situation in which accurate information is likely to be helpful for the recipient to achieve future success. Both studies showed that with increased age children's evaluations became significantly influenced by the social context, with the strongest effects seen among the 11-year-olds. These results suggest that Chinese children learn to take anticipated social consequences into account when making moral judgments about the appropriateness of telling a blunt truth versus lying to protect the feelings of others.

Philosophical debates about whether lying is ever morally acceptable have a long history (see Bok, 1978). Some philosophers have argued for a deontological position in which lying is always unacceptable (e.g., Kant, 1797/1949), while others have taken a more utilitarian perspective, in which the moral implications of lying are highly context dependent (e.g., Mill, 1869). The present study focuses on the ways in which children's developing beliefs conform to or diverge from these two philosophical positions. We examine this issue within the context of what are often called “white lie” or “politeness” situations, in which telling a lie is likely to result in more positive social consequences for the recipient than is telling a blunt truth.

Although many parents explicitly teach their children that lying is wrong in all cases (Heyman, Luu, & Lee, 2009), there is evidence that children tend to reject it. Perkins and Turiel (2007) found that adolescents judged lying to be wrong when it was done to cover up misdeeds, but they considered it acceptable under a number of other circumstances, such as in response to parental directives that were seen as violating moral precepts (e.g., a parent telling a child not to interact with a friend of another race). Other research suggests that younger children make distinctions among different types of lies, and do not consider all lies to be morally objectionable. For example, children as young as 4 years old believe that white lies are sometimes appropriate and can help to protect the feelings of others (Broomfield, Robinson, & Robinson, 2002). By this age, children also judge white lies less negatively than antisocial lies (Bussey, 1999). With increased age, children will not only increasingly value white lies for politeness purposes (Xu, Luo, Fu, & Lee, 2009; Xu, Bao, Fu, Talwar, & Lee, 2010) but also use such valuation to guide their actual actions in politeness situation (Xu et al., 2010).

Of interest in the present research is the possibility that children might make distinctions among different kinds of white lies. We sought to examine whether children's judgments of white lies would vary as a function of the consequences that are expected. If so, it would suggest that children's reasoning about communicative acts is not merely determined by their concerns for honesty but also affected by the social contexts in which communication takes place.

We selected China as a starting point for addressing children's context sensitivity in reasoning about white lies because of the emphasis on social context in East Asian cultures. There is evidence that people in East Asian cultures tend to place a high value on adjusting one's behavior to the role requirements of a range of social situations (Gao, 1998; Heine, 2001; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). A number of situational influences on behavior and self-perceptions have been seen in East Asian cultures that are not seen in North American cultures (Choi & Nisbett, 1998; Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001). For example, Kanagawa et al. (2001) found that Japanese adults wrote more modest self-descriptions in public than in private, but that American adults showed no such difference across the two contexts.

There is evidence that children who grow up in East Asian societies are also sensitive to whether communication takes place in a relatively private versus a public setting, at least in context where issues of modesty are involved. Yoshida, Kojo, and Kaku (1982) presented Japanese children ages 7 to 11 with a set of self-enhancement statements such as “I am good at drawing pictures,” and also a set of self-critical statements such as “I am not good at running.” When children were asked to select the statements that best described themselves, they chose more self-enhancing statements when their responses were made privately on a questionnaire as compared to verbally in the presence of ten classmates. These effects also extend to the evaluation of other people's behavior. Heyman, Itakura, and Lee (in press) found that Japanese children ages 7 to 11 judged the truthful acknowledgment of one's own good deed more negatively when it was made in front of an audience of classmates rather than in private due to their concerns for public display of immodesty. In contrast, there were no such effects of setting within a control group of children from the U.S. Other research suggests that Chinese children, like Japanese children, view immodest behavior as less acceptable in public than in private (Fu et al., 2010).

The present research examines whether Chinese children might show a similar kind of context sensitivity in politeness situations, by examining their evaluation of prosocial lies and blunt truths. In Study 1 we began by asking whether these statements are evaluated differently as a function of whether communication takes place in a relatively private one-on-one setting versus a more public setting. We predicted that children would evaluate white lies told in a public setting more favorably. This prediction is based on evidence that by age 5, children already have some understanding of “face” and its implications for self-presentation (Eskritt & Lee, 2009; Fu & Lee, 2007). For example, Fu and Lee (2007) found that 5 and 6 year old Chinese children give higher ratings to drawings when the adult illustrator of the drawing was present rather than absent. Because blunt truths told in public have higher risk to cause the recipient to lose “face” (Bond, 1986) than blunt truths told in private, the former may be viewed more negatively than the latter. By the same token, prosocial lies told in public are likely to have a greater potential to be face-saving for the recipient than are prosocial lies told in private, those told in public may be viewed more favorably.

In Study 2 we examined children's evaluation of prosocial lies and blunt truths with reference to two situations. In one situation, white lies actually have a high risk of causing the recipient to lose face in the long run. In contrast, in the other situation, no such positive consequences could reasonably be expected and thus white lies are less likely to cause the recipient to lose face in the future. With these two situations, we examined whether participants would consider telling a blunt truth to be more acceptable if it helped the recipient to identify weaknesses that if corrected could improve future performance and produce a favorable reception from future audiences. We predicted this pattern of response in light of evidence that Chinese children place a high value on helping others to improve their performance (Heyman, Fu, & Lee, 2008; Heyman, Fu, Sweet, & Lee, 2009).

We examined these issues with children ranging in age from 7 to 11 years of age. This age range was selected because by age 7 children think about white lies primarily in terms of how they might impact others (Broomfield et al., 2002; Heyman, Sweet, & Lee, 2009). Additionally, it is clear that children in this age range have the basic capacity to take the social context of communication into account when making judgments about the types of communication that are appropriate, and that this capacity undergoes substantial development across this time period (Aloise-Young, 1993; Banerjee, 2002; Banerjee & Yuill, 1999; Gee & Heyman, 2007; Watling & Banerjee, 2007). Finally, the types of measures included in the present study have been validated for children of this age (Lee, Cameron, Xu, Fu, & Board, 1997; Lee, Xu, Fu, Cameron, & Chen, 2001; Xu et al., 2010). Given evidence that children younger than 7 show some sensitivity to context when reasoning about communication that has evaluative implications (Banerjee, 2002; Gee & Heyman, 2007; Fu and Lee, 2007), one might expect to see an effect of context even in the youngest age groups. However, it would also be reasonable to predict that no such effects would emerge until around age 11, when children develop nuanced views of the role of interpersonal process goals in communication (Bennett & Yeeles, 1990). There is also evidence suggesting that in East Asia children develop increased sensitivity to the public/private distinction at about early adolescence (Heyman, Itakura, & Lee, in press; Fu et al., 2010).

Study 1

The objective of Study 1 was to examine the way 7-, 9-, and 11-year-olds make moral evaluations of children's truth telling and lie telling in a politeness context. Of interest was whether children make distinctions between statements made in public versus a private one-on-one context.

Method

Participants

Participants were 144 children from Beijing, China in the Haidian District. There were equal numbers of boys and girls from each of three age groups; forty-eight children were 7 years old (M = 6.86 years, SD = 0.52), forty-eight children were 9 years old (M = 8.81 years, SD = 0.51), and forty-eight children were 11 years old (M = 10.87 years, SD = 0.51).

Students attended public schools and were from primarily working-class and middle-class families. Approximately 60% of participants had at least one parent with some form of vocational or university education. Almost all children were of the Han nationality, which is the predominant ethnic group (over 90% of the population) in China.

Procedure

Participants were tested by a trained experimenter in individual sessions at their schools. All stimuli were developed in Mandarin by native Mandarin speakers, and children were also tested in this language. For each participant, the experimenter read eight stories that were presented in one of four different randomized orders. The overall study design was 3 (Age Group: 7, 9, or 11) by 2 (Story Type: experimental, control) by 2 (Setting: public, private) by 2 (Truth Value: truth, lie), with Age as a between-subjects factor and the others as within-subjects factors. The dependent variable was children's evaluative judgments of story characters' truthful or untruthful statements.

An example of each story type is presented in the Appendix. Four of these stories were experimental stories, which described a protagonist who faces a politeness situation with a peer. Specifically, in each of these stories a peer directs the protagonist's attention to a particular item, such as a new schoolbag, and asks the protagonist whether he or she likes it. In each case the protagonist does not like the item, and either truthfully acknowledges this negative impression, or falsely states that he or she has a positive impression of the item. These statements are made either in a public setting (in front of the class) or in a private setting (in the presence of the peer only). The public and private versions of each story were always read consecutively, with the order of the versions counterbalanced between participants. The specific story content was counterbalanced between participants to prevent specific story content from having undue influences on children's evaluations. The following is a translation of two of the experimental stories (for other stories, see the Appendix).

White lie in a public setting

“Pengpeng and Xiaohua were in the same class. Both of them, along with their classmates, were playing outside during recess. Xiaohua asked Pengpeng, ‘How do you like my new shoes?’ Pengpeng thought her shoes were very ugly and she didn't like them. But Pengpeng said in front of the class, ‘They are very beautiful.’”

White lie in a private setting

“Xiaoming and Ningning were in the same class. They went home together after school. Ningning asked Xiaoming, ‘How do you like my new schoolbag?’ Xiaoming thought her bag was very ugly and she didn't like it. But Xiaoming said when nobody else was around, ‘It's very beautiful.’”

Participants were presented with an additional set of four control stories (see the Appendix). These stories followed the form of the experimental stories and used the same rating scale, but did not involve issues of politeness. The control stories were included in an effort to insure that any effects that might be seen would not be explainable in terms of global beliefs about lying and truth-telling, or general tendencies in children's use of the scale. In this way, any pattern of results seen with the experimental stories but not the control stories could be interpreted as being specific to the politeness context.

In the control stories, as in the experimental stories, the protagonist's response to a particular item is described. However, the protagonist is described as liking the item (e.g., a school bag), rather than disliking it. In the control stories, like the experimental stories, the protagonist either tells the truth or a lie to the other story character and these truthful or untruthful statements are made either in a public setting (in front of the class) or in a private setting (in the presence of the peer only). As in the experimental stories, there were public and private versions of each story, which were always read consecutively. The specific story content was also counter-balanced between subjects.

Following each story, participants were asked to make an evaluative judgment by indicating whether the protagonist's statement was good or bad. Participants indicated their responses on a seven-point Likert-type scale that has been successfully used in prior research with children this age range (e.g., Lee et al., 1997, 2001). The scale consists of the response options very, very good (represented by three red stars, scored as 3), very good (represented by two red stars, scored as 2), good (represented by one red star, scored as 1), neither good nor bad (represented by a blank circle, scored as 0), bad (represented by one black X, scored as -1), very bad (represented by two black Xs, scored as -2), and very, very bad (represented by three black Xs, scored as -3). Participants were trained to use the scale during an initial session in which they were asked to verify what each point on the scale referred to.

Results

Preliminary results revealed no significant effects of participants' gender, and consequently this variable was dropped from the analyses. Because the main hypotheses focused specifically on how children responded to the stories in the politeness situations, separate ANOVAs were performed on the results from the experimental and control conditions.

(1) Politeness Stories

Politeness stories: combined

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (truth value: truth, lie) by 2 (setting: public, private) repeated measures ANOVA with the last two factors as repeated measures was performed on children's evaluative judgments of the protagonist's statements. There was a significant main effect of age (F [2, 141] = 7.95, p = .001, partial η2 = 0.10), and a significant two-way interaction between truth value and setting (F [1, 141] = 26.09, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.16; for details of these effects, see Table 1). These effects were further qualified by a significant three-way interaction between truth value, setting, and age (F [2, 141] = 6.03, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.08).

Table1.

Means and standard deviations of significant effects in Study 1.

| Politeness stories: combined | ||

| Age main effect | ||

| Politeness stories | ||

| 7 years (n=48) | - 0.80 (2.20) | |

| 9 years (n=48) | - 0.32 (2.09) | |

| 11 years (n=48) | 0.07 (2.02) | |

| Truth value and setting interaction | ||

| Public Setting | Private Setting | |

| Truth telling | - 0.60 (2.21) | - 0.12 (2.08) |

| Lie telling | - 0.11 (2.20) | - 0.56 (1.99) |

| Control stories: combined | ||

| Truth value main effect | ||

| Truth telling | 2.66 (0.61) | |

| Lie telling | - 2.15 (0.82) | |

| Setting main effect | ||

| Public setting | 0.19 (2.55) | |

| Private setting | 0.32 (2.48) | |

| Age main effect | ||

| 7 years | 0.31 (2.60) | |

| 9 years | 0.33 (2.44) | |

| 11 years | 0.12 (2.50) | |

To examine the setting- and age-related differences on children's ratings of blunt truth-telling and white lie-telling stories, we further conducted two separate post hoc ANOVAs with alpha set at .05 (LSD).

Politeness stories: truth telling

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (setting: public, private) ANOVA was conducted on children's ratings of the blunt truth-telling stories. There was a significant main effect of setting (F [1, 141] = 15.69, p < .001, partial η 2 = 0.10) and a significant main effect of age (F [2, 141] = 5.57, p < .01, partial η 2 = 0.07; for details of these effects, see Table 1).

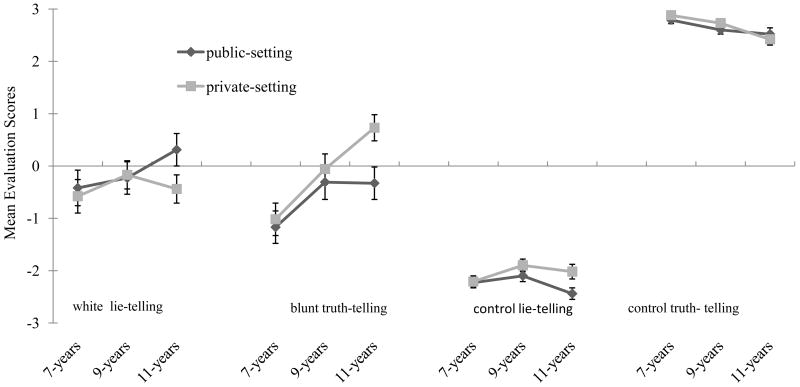

These effects were further qualified by a significant two-way interaction between setting and age (F [2, 141] = 5.58, p < .01, partial η 2 = 0.07). As shown in Figure 1, simple effect analyses of the setting by age interaction revealed that the setting-related differences were significant only for the 11-year-olds (F [1, 141] = 24.99, p < .001, partial η 2 = 0.15). Eleven-year-olds rated the blunt truth-telling story more negatively in the public setting (M = -0.33, SD = 2.14) than in the private setting (M = 0.73, SD = 1.72), and no setting-related differences were found for 7-year-olds and the 9-year-olds.

Figure 1.

Mean scores (standard errors) of children's evaluation in the public and private settings in Study 1.

Politeness stories: lie telling

A 3 (age: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (setting: public, private) ANOVA was conducted on children's ratings of the white lie stories. There was a main effect of setting (F [1, 141] = 18.51, p < .001, partial η 2 = 0.12, see Table 1), which was qualified by a marginally significant two-way interaction between setting and age (F [2, 141] = 2.58, p = .079, partial η 2 = 0.04. As shown in Figure 1, simple effect analysis revealed that the setting differences were significant for 9- and 11-year-olds but not 7-year-olds. Nine-year-olds rated the lie-telling stories less negatively in the public setting (M = -0.23, SD = 2.13) than in the private setting (M = -0.67, SD = 1.88). Eleven-year-olds differentiated even more strongly between the settings, rating white lie-telling positively when done in public (11-years: M = 0.31, SD = 2.14) and negatively when done in private (11-years: M = -0.44, SD = 1.87).

(2) Control Stories

Control condition: combined

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (truth value: truth, lie) by 2 (setting: public, private) repeated measures ANOVA with the last two factors as repeated measures was performed on children's evaluative judgments of the protagonist's statements. There were significant main effects of truth value (F [1, 141] = 3456.44, p < .001, partial η 2 = 0.96), setting (F [1, 141] = 8.61, p < .01, partial η 2 = 0.06), and age (F [2, 141] = 5.23, p < .01, partial η 2 = 0.07; for details of these effects, see Table 1). These main effects were qualified by a three-way interaction among truth value, setting, and age (F [2, 141] = 3.62, p < .05, partial η2 = 0.05).

To examine the setting- and age-related differences on children's ratings of the control truth telling and lie telling stories, we further conducted two separate post hoc ANOVAs with alpha set at .05 (LSD).

Control condition: truth telling

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (setting: public, private) ANOVA was conducted on children's ratings of the control truth-telling stories. There was a significant main effect of age (F [2, 141] = 6.93, p = .001, partial η 2 = 0.09). Seven-year-olds (M = 2.83, SD = 0.43) rated the control truth-telling stories more positively than did the 11-year-olds (M = 2.67, SD = 0.54) and the 9-year-olds (M = 2.47, SD = 0.77), with the latter two groups showing no differences from each other.

Control condition: lie telling

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (setting: public, private) ANOVA was conducted on children's ratings of the control lie-telling stories. There was a main effect of setting (F [1, 141] = 10.39, p < .01, partial η 2 = 0.07), which is qualified by a marginally significant age by setting interaction (F [2, 141] = 2.93, p = .057, partial η 2 = 0.04). Simple effect analysis revealed that the setting differences were significant for 9- and 11-year-olds, who rated the lie-telling stories more negatively in the public setting (9-years: M = -2.10, SD = 0.78; 11-years: M = -2.44, SD = 0.74) than in the private setting (9-years: M = -1.90, SD = 0.83; 11-years: M = -2.02, SD = 1.00).

Discussion

For the politeness stories, older children, particularly 11-year-olds, took into consideration of the setting factor when making evaluations. They viewed telling white lies less negatively in public than in private and blunt truth-telling less positively in public than in private. A likely explanation for these differences is that the recipients of the information are at greater risk of losing face in a public rather than a private setting (Bond, 1986): blunt truths are thus seen particularly inappropriate in public, whereas white lies in this situation are seen as a way to avoid these negative consequences. The age differences likely reflect the gradual socialization of such ideas in Chinese children in the elementary school years.

The results from the control stories, which did not involve a conflict between telling the truth and protecting the feelings of the recipient, rule out the alternative interpretation that the setting differences simply reflect a general tendency to believe that the truth is better told in private and that lies are better told in public. Specifically, there was no effect of setting on truth telling in these stories, and the lie telling effects were opposite to what was seen in the politeness stories, with older children rating lie telling more negatively in the public than in private.

Further, it is worth noting that regardless of settings children at all age groups rated white lies less negatively than harmful lies and blunt truths less positively than helpful truths. This finding suggests that even 7-year-olds are aware that the moral value of a verbal statement depends not only on its truthfulness, but also on whether it serves to help or harm its recipient.

Study 2

Study 1 was designed to examine the way 7-, 9-, and 11-year-olds make moral evaluations of truth telling and lie telling in public politeness contexts, where the blunt truth is likely to have higher negative consequences for recipients than it has in private. The objective of Study 2 was to examine whether moral judgments are influenced by the potential of the blunt truth to have positive consequences, and that of a white lie to have a negative consequence, for the recipient in a long run. We compared children's reasoning about a situation in which accurate feedback could be expected to make a positive contribution to the future performance of the recipient and in which white lies may have a high risk for the recipient to lose face in the future (a high recipient consequence situation) to a situation in which there would be no such expectations (a low recipient consequence situation).

Method

Participants

Participants were 96 children from Beijing, China. None had participated in Study 1, but all were from the same population as those in Study 1. Thirty-two children were 7 years old (16 boys; M = 7.30 years, SD = 0.42), thirty-two children were 9 years old (16 boys; M = 9.06 years, SD = 0.36), and thirty-two children were 11 years old (17 boys; M = 11.22 years, SD = 0.31).

Procedure

The procedure was the same as in Study 1, except that the manipulation involved the likely future consequences of the protagonist's statement rather than whether the interaction took place in a public or private setting. The counterbalancing and randomization were done the same way as in Study 1. The overall study design was 3 (Age Group: 7, 9, or 11) by 2 (Story Type: experimental, control) by 2 (Recipient consequence: high, low) by 2 (Truth Value: truth, lie), with the last three serving as within-subjects factors. The dependent variable was children's evaluative judgments of story characters' truthful and untruthful statements.

An example of each story type is presented in the Appendix. The following is a translation of two of the experimental stories (see the Appendix for all stories).

White lie high recipient consequence story

“Xiaojing and Wenwen were in the same class. Wenwen told Xiaojing, ‘I made a model of an airplane that I will submit in a competition’, and showed her the airplane. Wenwen asked, ‘What do you think of my airplane model?’ Xiaojing didn't think it was very good, but she said, ‘Your model is very good.’”

White lie low recipient consequence story

“Xiaoan and Lili were in the same class. Lili told Xiaoan, ‘I made a model of an airplane that I want to give you as a gift’, and showed her the airplane. Lili asked, ‘What do you think of my airplane model?’ Xiaoan didn't think it was very good, but she said, ‘Your model is very good.’”

Results

(1) Politeness Stories

Politeness stories: combined

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (gender) by 2 (truth value: truth, lie) by 2 (recipient consequence: high, low) repeated measures ANOVA with the last two factors as within-subjects factors was performed on children's evaluative judgments of the protagonist's statements. There were significant two-way interactions between truth value and recipient consequence (F [1, 90] = 28.69, p < .001, partial η 2 = 0.24), between truth value and gender (F [1, 90] = 23.76, p < .001, partial η 2 = 0.21), and between gender and age (F [2, 90] = 3.68, p < .05, partial η2 = 0.08). Table 2 shows the relevant means and standard deviations that illustrate the significant effects.

Table2.

Means and standard deviations of significant effects in Study 2.

| Politeness stories: combined | ||

| Truth value and Recipient consequence interaction | ||

| High recipient consequence | Low recipient consequence | |

| Truth telling | 0.11 (2.16) | - 0.39 (2.08) |

| Lie telling | - 0.70 (2.00) | 0.17 (2.09) |

| Truth value and Gender interaction | ||

| Boy | Girl | |

| Truth telling | - 0.55 (2.08) | 0.81 (2.03) |

| Lie telling | - 0.88 (2.22) | - 1.34 (1.51) |

| Gender and Age interaction | ||

| Boy | Girl | |

| 7 years (n=32) | 0.33 (2.27) | - 0.47 (2.16) |

| 9 years (n=32) | - 0.72 (2.04) | - 0.03 (2.03) |

| 11 years (n=32) | - 0.24 (2.05) | - 0.07 (1.97) |

| Control stories: combined | ||

| Truth value main effect | ||

| Truth telling | 2.58 (0.73) | |

| Lie telling | - 1.83 (1.32) | |

| Recipient consequence main effect | ||

| High recipient consequence | 0.43 (2.41) | |

| Low recipient consequence | 0.31 (2.50) | |

| Truth value and Age interaction | ||

| Truth telling | Lie telling | |

| 7-years | 2.88 (0.33) | - 2.02 (1.08) |

| 9-years | 2.75 (0.50) | - 1.89 (1.20) |

| 11-years | 2.11 (0.96) | - 1.59 (1.62) |

| Recipient consequence and Age interaction | ||

| High recipient consequence | Low recipient consequence | |

| 7-years | 0.44 (2.55) | 0.42 (2.63) |

| 9-years | 0.41 (2.54) | 0.45 (2.49) |

| 11-years | 0.45 (2.17) | 0.06 (2.40) |

However, the above significant two-way interactions were further qualified by a significant three-way interaction among truth value, recipient consequence, and age (F [2, 90] = 8.01, p = .001, partial η 2 = 0.15). To examine this interaction further, we conducted two separate post hoc ANOVAs with alpha set at .05 (LSD).

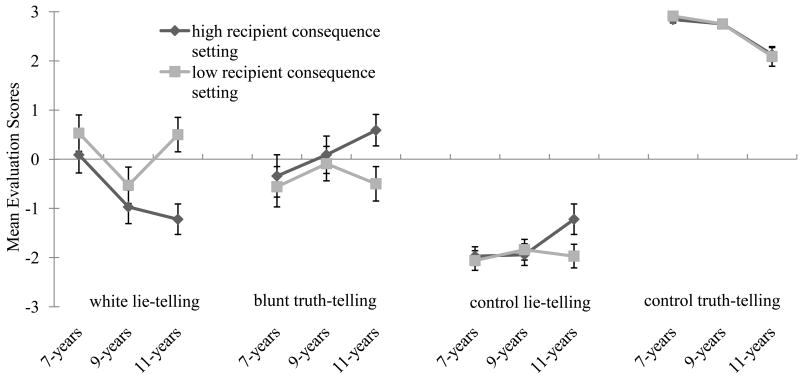

Politeness stores: truth telling

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (recipient consequence: high, low) ANOVA was conducted on children's ratings of the truth telling stories. There was a main effect of recipient consequence (F [1, 93] = 10.99, p = .001, partial η2 = 0.11). There was also a significant two-way interaction between recipient consequence and age (F [2, 93] = 3.88, p < .05, partial η2 = 0.08). As shown in Figure 2, simple effect analysis revealed that the recipient consequence differences were significant only for 11-year-olds, who rated to the truth-telling stories more positively in the high recipient consequence condition (M = 0.59, SD = 1.83) than in the low recipient consequence condition (M = -0.50, SD = 2.16).

Figure 2.

Mean scores (standard errors) of children's evaluation in the high and low recipient consequence conditions in Study 2.

Politeness stores: lie telling

A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (recipient consequence: high, low) ANOVA was conducted on children's ratings of the white lie stories. There was a significant main effect of recipient consequence (F [1, 93] = 24.52, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.21), which was modified by a two-way interaction between condition and age (F [2, 93] = 5.98, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.11). As shown in Figure 2, simple effect analysis revealed that the recipient consequence differences were significant only for the 11-year-olds, who rated the lie-telling stories more negatively in the high recipient consequence condition (M = -1.22, SD = 1.76) than in the low recipient consequence condition (M = 0.50, SD = 1.97).

(2) Control Stories

Because preliminary analysis revealed no significant effects of gender, it was not included in the analyses of the control stories. A 3 (age group: 7, 9, 11) by 2 (truth value: truth, lie) by 2 (recipient consequence: high, low) repeated measures ANOVA with the last two factors as within-subjects factors was performed on children's evaluative judgments of the protagonist's statements. There was a significant main effect of truth value (F [1, 93] = 1259.82, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.93), and a marginally significant main effect of recipient consequence (F [1, 93] = 3.44, p = .067, partial η2 = 0.04). These effects were modified by two significant two-way interactions. One was between truth value and age (F [2, 93] = 8.46, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.15). As shown in Figure 2, simple effect analyses of truth value by age interaction revealed that age-related differences were significant only in the control truth-telling stories: the 11-year-olds (M = 2.11, SD = 0.96) rated the control truth-telling stories less positively than did the 7-year-olds (M = 2.88, SD = 0.33) and the 9-year-olds (M = 2.75, SD = 0.50), whereas the two younger age groups did not differ from each other in their ratings. For the control lie-telling story, the age differences were not significant. The other two-way interaction was between recipient consequence and age (F [2, 93] = 4.47, p < .05, partial η2 = 0.09). As shown in Table 2, simple effect analyses revealed that recipient consequence difference was significant only for 11-year-olds, who rated the control stories less negatively in the high recipient consequence condition (M = -1.22, SD = 1.77) than in the low recipient consequence condition (M = -1.97, SD = 1.38).

Discussion

In response to the scenarios in which telling the truth was consistent with helping to prevent the recipient to lose face in a long run, 11-year-olds but not younger ones viewed telling the blunt truth more favorably and telling white lies less favorably. These findings suggest the older children's consideration of the long term social consequences of telling the truth versus telling a white lie in the politeness contexts extends beyond an awareness of the public/private distinction, and that when older Chinese children make moral evaluations of blunt truth and white lie telling they take into account the future expected benefits and risks for recipients.

As in Study 1, the results of the control stories, in which there is no conflict between telling the truth and protecting the feelings of the recipient, rule out the possibility that the results can be explained in terms of general patterns of reasoning being applied to the different situations. More tellingly, as shown in Figure 2, the age patterns for both lie-telling and truth-telling in the control conditions were markedly different from those in the experimental conditions.

There were significant interactions involving gender that were not predicted, including the finding that boys viewed telling a white lie more positively, and telling a blunt truth more negatively, than did girls. Further research will be needed to determine whether this gender difference is replicable, and if so, how it can be explained.

General Discussion

This research examined children's moral evaluations of lying and truth telling in situations in which telling the truth or a lie is likely to have short- or long-term consequence for the recipient. Of interest was whether children's judgments would be consistent with a utilitarian philosophical perspective, in which the moral implications of lying are highly context dependent (e.g., Mill, 1869). Chinese children were asked to make moral judgments about lying and truth telling in situations that varied in the expected social consequences for recipients. We examined this issue in China because there is a strong emphasis on the social context in which communication takes place (Gao, 1998; Bond, 1986). In Study 1 we examined whether children's moral evaluations of truth telling and lie telling would vary based on whether telling the truth could be expected to cause recipients to lose face. In Study 2 we examined whether children's evaluations would vary based on whether telling a blunt truth could be expected to help the recipient to succeed in the future.

The older children in each study showed the predicted sensitivity to social context. In Study 1, older children, particularly 11-year-olds, considered telling the blunt truth to be more acceptable in private than in public, and telling a white lie telling as more acceptable in public than in private. These findings suggest that in making their judgments, older children took into account the potential for recipients to lose face. In Study 2, 11-year-olds viewed telling a blunt truth more favorably and telling a white lie less favorably if offering accurate feedback could help the recipient to achieve future success and avoid losing face in the long run, which suggests their reasoning extends beyond the immediate situation. The expected consequences included helping the recipient to save face in front of future audiences, or helping the recipient to make better decisions about trying harder and adopting new strategies.

It should be noted that although the younger children's evaluation did not vary depending on the contexts in which the truth or a lie was uttered, they clearly differentiated lies and truths in politeness situations and those in which lies were told to conceal a transgression and truths were told to confess about it. This is evidenced by the fact that they rated lies in the experimental stories less negatively than the control harmful lies and truths in the experimental stories less positively than helpful truths. This is consistent with the existing findings about children's moral evaluations of blunt truths and white lies (Broomfield et al., 2002; Bussey, 1999; Xu et al., 2009; Xu et al, 2010).

The present results, taken together with the existing findings, suggest that children may begin to show differentiation in their moral evaluations regarding large situational differences such as politeness and non-politeness related lie- and truth-telling at preschool ages (e.g., Bussey, 1999). With increased age, they become increasing sensitive to more nuanced differences regarding the settings of lie- and truth-telling within the politeness situation. Our results show that by 11 years of age, children clearly show the understanding that telling white lies or the blunt truth may have differential consequences on the recipient and thus entail differential moral values. One possible explanation for the age difference is that the older Chinese children have had more experience being socialized to attend to contextual factors relating to how communication affects recipients. Alternatively, older children may be better able to notice or attend to contextual factors due to their relatively greater cognitive sophistication. Yet another possibility is that children of different ages may interpret the same contextual factors differently. For example, older children might consider the consequences of failing in a competition to be more severe than do younger children.

There may also be individual differences in how children of the same age interpreted the consequences of specific situations. For example, some participants may have expected recipients to respond to the blunt truth in the high consequence experimental situation of Study 2 by taking further action to insure success. In contrast, others may have expected recipients to respond to the blunt truth in such situations by deciding not to enter the competition because there was no meaningful chance to win. In future research, it will be important to assess these kinds of perceived consequences, and any association they may have with children' evaluative judgments (see Heyman, Fu, Sweet, & Lee, 2009).

Because the present study only included Chinese children, further research will be needed to determine how the results will extend to other populations, including Western children. Previous research suggests that when evaluating truth telling and lie telling, Western children may be less sensitive to certain aspects of the social context than are children in East Asia (Wang, 2006). For example, Western children do not always make public/private distinctions in contexts in which East Asian children do (Heyman et al., in press). However, it is also the case that Western children sometimes show sensitivity to this distinction when the public and private distinctions are made highly salient (Eskritt & Lee, 2009) and there are cases in which Western adults communicate differently in public versus private settings (e.g., Baumeister & Ilko, 1995; DePaulo & Bell, 1996).

Previous research suggests that the same evaluative feedback can have different implications within different cultures (Heyman et al., 2008). Consequently, it is not clear whether what we defined as a high recipient consequence story in Study 2 would be viewed by children in the West as has having similar consequences for recipients. It is possible that the benefits of telling the blunt truth in high consequence situations rests on a cultural belief that negative value-laden feedback often serves to motivate recipients to undertake new strategies or increased effort. The evidence to date suggests that this cultural belief is substantially stronger in China than in the U.S. (Heyman et al., 2008; Heyman, Fu et al., 2009).

It is possible that people in the West are also highly sensitive to social context, but in different ways. For example, one important distinction concerning lying and truth telling in the West involves the closeness of the relationship between communication partners (DePaulo & Kashy, 1998). It may also be that people in the West have a greater tendency to focus on individual personality. For example, the blunt truth may be seen as less acceptable when the recipient is thought to be highly sensitive.

The present paper focuses on how children's moral evaluations are influenced by the consequences for recipients. However, it is important to note that truth telling and lie telling also carry potential consequences for other individuals, including the speaker. Consequently, it will be important to examine how children learn to assess and weigh the consequences for different individuals in such situations. Additionally, although prior research suggests that reasoning in lying and truth telling situations is predictive of children's real world behavior (Xu et al., 2010), the extent to which this is true in politeness situations in particular will be an important topic for future research.

Conclusion

The present research provides evidence that Chinese children learn to take the expected consequences for recipients into account when they evaluate truth telling and lie telling in politeness situations. These findings suggest that Chinese children engage in a cost-benefit analysis when deciding what to say in situations in which telling a blunt truth is likely to hurt the feelings of others, confirming the notion that children are holding a utilitarian perspective about the moral values of lying and truth-telling at least in the politeness situations.

Appendix

Study 1 Example Stories

Politeness Stories

1. Public Setting

Story 1.1

Wanghao and Xiaoyu were in the same class. On an autumn outing, Wanghao gave one of his apples to Xiaoyu, and Xiaoyu began to eat it. Xiaoyu thought it was very sour and he didn't like it. Wanghao asked Xiaoyu, “How do you like this apple?” Xiaoyu said in front of the class, “It is not good.” [“It is very good.”]

Story 1.2

Pengpeng and Xiaohu were in the same class. Both of them along, with their classmates, were playing outside during recess. Xiaohua asked Pengpeng, “How do you like my new coat?” Pengpeng thought her coat was not very lovely and she didn't like it. Pengpeng said in front of the class, “It is ugly.” [“It is very beautiful.”]

2. Private Setting

Story 2.1

Xiaowei and Zhangning were in the same class. Xiaowei was eating a piece of cake during recess when her classmate Zhangning came over to see her. Xiaowei gave Zhangning a piece of the cake and Zhangning started to eat it. Zhangning thought the cake was very hard and she didn't like it. Xiaowei asked Zhangning, “How do you like the cake?” Zhangning said, when nobody was around, “It is not good.” [“It is very good.”]

Story 2.2

Xiaoming and Ningning were in the same class. They went home together after school. Ningning asked Xiaoming, “How do you like my new schoolbag?” Xiaoming thought her bag was very ugly and she didn't like it. But Xiaoming said, when nobody was around, “It is ugly.” [“It's very beautiful.”]

Control Stories

3. Public Setting

Story 3.1

Wanghao and Xiaoyu were in the same class. Wanghao gave candy to his classmates, and Xiaoyu started to eat it. Xiaoyu thought it was very sweet and he liked it. Wanghao asked Xiaoyu, “How do you like this candy?” Xiaoyu said in front of the class, “It is very good.” [“It is not good.”]

Story 3.2

Pengpeng and Xiaohua were in the same class. Both of them, along with their classmates, were going to school. Xiaohua asked Pengpeng, “How do you like my new schoolbag?” Pengpeng thought her bag was very lovely and she liked it. Pengpeng said in front of the class, “It is very beautiful.” [“It is ugly.”]

4. Private Setting

Story 4.1

Dingding and Xiaoli were in the same class. Xiaoli was playing at Dingding's house. Dingding gave him an orange, and Xiaoli began to eat it. Xiaoli thought it was very sweet and he liked it. Dingding asked Xiaoli, “How do you like the orange?” Xiaoli said, when nobody was around, “It is very good.” [“It is not good.”]

Story 4.2

Tiantian and Xiaoqi were in the same class. During recess they were jumping rope on the playground. Tiantian asked Xiaoqi, “How do you like my new shoes?” Xiaoqi thought her new shoes were very lovely and she liked them. Xiaoqi said, when nobody was around, “They are very beautiful.” [“They are not beautiful.”]

Study 2 Example Stories

Politeness Stories

1.1. High Recipient Consequence Condition

Ke and Ming were in the same class. Ke told Ming, “I made a painting that I would like to send to a competition,” and showed Ming the painting. Ke asked, “What do you think of my painting?” Ming didn't think it was good, and he said, “Your painting is not good.” [“Your painting is very good.”]

1.2. Low Recipient Consequence Condition

Li and Mei were in the same class. Li told Mei, “I made a painting that I want to give you as a gift,” and handed her a painting. Li asked, “What do you think of my painting?” Mei didn't think it was good, and she said, “Your painting is not good.” [“Your painting is very good.”]

Control Stories

2.1. High Recipient Consequence Condition

Li and Yang were in the same class. Li told Yang, “I made a model of an airplane that I would like to send to a competition,” and showed it to him. Li asked, “What do you think of my model airplane?” Yang thought it was very good, and he said, “Your model is very good.” [“Your model is not good.”]

2.2. Low Recipient Consequence Condition

Ning and Shan were in the same class. Ning told Shan, “I made a model of an airplane that I want to give you as a gift,” and showed it to her. Ning asked, “What do you think of my model airplane?” Shan thought it was good, and she said, “Your model is very good.” [“Your model is not good.”]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Fengling Ma, State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Beijing Normal University.

Fen Xu, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University.

Gail D. Heyman, University of California, San Diego

Kang Lee, University of Toronto.

References

- Aloise-Young PA. The development of self-presentation: Self-promotion in 6- to 10-year-old children. Social Cognition. 1993;11:201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R. Audience effects on self-presentation in childhood. Social Development. 2002;11:487–507. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Yuill N. Children's explanations for self-presentational behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;29:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Ilko SA. Shallow gratitude: Public and private acknowledgement of external help in accounts of success. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1995;16:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M, Yeeles C. Children's understanding of showing off. Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;130:591–596. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1990.9922930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok S. Lying: Moral choice in public and private life. New York: Pantheon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bond MH. Lifting one of the last bamboo curtains: Review of the psychology of the Chinese people. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield KA, Robinson EJ, Robinson WP. Children's understanding about white lies. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K. Children's categorization and evaluation of different types of lies and truths. Child Development. 1999;70:1338–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Choi I, Nisbett RE. Situational salience and cultural differences in the correspondence bias and actor-observer bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:949–960. [Google Scholar]

- DePaulo BM, Bell KL. Truth and investment: Lies are told to those who care. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:703–716. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaulo BM, Kashy DA. Everyday lies in close and casual relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:63–79. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskritt M, Lee K. Children's informational reliance during inconsistent communication: The public–private distinction. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2009;104:214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G, Brunet MK, Lv Y, Ding X, Heyman GD, Cameron CA, Lee K. Chinese Children's moral evaluation of lies and truths: Roles of context and parental individualism-collectivism tendencies. Infant and Child Development. 2010 doi: 10.1002/icd.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G, Lee K. Social grooming in the kindergarten: The emergence of flattery behavior. Developmental Science. 2007;10:255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. “Don't take my word for it.”--understanding Chinese speaking practices. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1998;22:163–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gee CL, Heyman GD. Children's evaluation of other people's self-descriptions. Social Development. 2007;16:800–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ. Self as cultural product: An examination of East Asian and North American selves. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:881–905. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Fu G, Lee K. Reasoning about the disclosure of success and failure to friends among children in the United States and China. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:908–918. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Fu G, Sweet MA, Lee K. Children's reasoning about evaluative feedback. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27:875–890. doi: 10.1348/026151008x390870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Itakura S, Lee K. Japanese and American children's reasoning about accepting credit for prosocial behavior. Social Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00578.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Luu DH, Lee K. Parenting by lying. Journal of Moral Development. 2009;38:353–369. doi: 10.1080/03057240903101630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Sweet MA, Lee K. Children's reasoning about lie-telling and truth-telling in politeness contexts. Social Development. 2009;18:728–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagawa C, Cross SE, Markus HR. “Who am I?”: The cultural psychology of the conceptual self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kant I. On a supposed right to lie from altruistic motives. In: Beck LW, editor. Critique of practical reason and other writings. Chicago: IL: University of Chicago Press; 1797/1949. pp. 346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Cameron CA, Xu F, Fu G, Board J. Chinese and Canadian children's evaluations of lying and truth-telling. Child Development. 1997;64:924–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Xu F, Fu G, Cameron CA, Chen S. Taiwan and mainland Chinese and Canadian children's categorization and evaluation of lie- and truth-telling: A modesty effect. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2001;19:525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mill JS. On liberty. London: Longman, Roberts & Green; 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins SA, Turiel E. To lie or not to lie: To whom and under what circumstances. Child Development. 2007;78:609–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Culture and the development of self-knowledge. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Watling D, Banerjee R. Children's understanding of modesty in front of peer and adult audiences. Infant and Child Development. 2007;16:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Luo YC, Fu G, Lee K. Children's and adults' conceptualization and evaluation of lying and truth-telling. Infant and Child Development. 2009;18:307–322. doi: 10.1002/icd.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Bao X, Fu G, Talwar V, Lee K. Lying and truth-telling in children: From concept to action. Child Development. 2010;81:581–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Kojo K, Kaku H. A study on the development of self-presentation in children. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology. 1982;30:120–127. [Google Scholar]