Abstract

Theranostics, the fusion of therapy and diagnostics for optimizing efficacy and safety of therapeutic regimes, is a growing field that is paving the way towards the goal of personalized medicine for the benefit of patients. The use of light as a remote-activation mechanism for drug delivery has received increased attention due to its advantages in highly specific spatial and temporal control of compound release. Photo-triggered theranostic constructs could facilitate an entirely new category of clinical solutions which permit early recognition of the disease by enhancing contrast in various imaging modalities followed by the tailored guidance of therapy. Finally, such theranostic agents could aid imaging modalities in monitoring response to therapy. This article reviews recent developments in the use of light-triggered theranostic agents for simultaneous imaging and photoactivation of therapeutic agents. Specifically, we discuss recent developments in the use of theranostic agents for photodynamic-, photothermal- or photo-triggered chemo-therapy for several diseases.

Keywords: Photodynamic Therapy, Nanotechnology, Photothermal Therapy, Cancer, Infections, Imaging, Diagnostics, Targeting, Multifunctional, Drug Delivery

1. Introduction

Global healthcare costs have been rising steeply over the last decade [1]. However there hasn’t been a dramatic reduction in disease related deaths to warrant such a drastic rise in costs [2]. During this time there has been a paradigm shift in disease management and clinicians are gradually moving from the traditional “one drug fits all” approach towards the idea of personalized medicine – ‘the right drug for the right person administered at the right time’ [3–4]. Although significant awareness has been created about personalized medicine, its full potential has yet to be tapped [5–6]. The field of theranostics has sprung from the recognition that heterogeneous diseases require more personalized solutions [7]. Theranostics refers to the fusion of therapy and diagnostics, with the purpose of optimizing efficacy and safety, as well as streamlining the process of drug development and as a field is still in its infancy. The convergences of a number of scientific breakthroughs have made the development of theranostics possible [8]. In the field of biology, the human genome project and the development of biomarker initiatives, among others, have enhanced the understanding of disease progression. Technologies such as genotyping or gene expression profiling make it possible to transfer this newly acquired biological knowledge into the development of diagnostic tests [8]. Theranostics empower physicians with high-medical value testing for science-driven treatment decisions; improve patient outcomes and patient safety by identifying patients who won’t respond to a drug or who are likely to experience an adverse event; increase the efficiency of drug development, helping pharmaceutical companies by pinpointing those patients most likely to benefit from the new drug; and positively impact health economics, thus helping physicians select optimal and cost effective therapy. Although there is broad agreement that this nascent field has much potential in improving healthcare, there are a number of challenges that need to be overcome before it translates into routine use in the clinic [8]. Chief among these hurdles is the availability and use of a single platform for diagnosis and therapy.

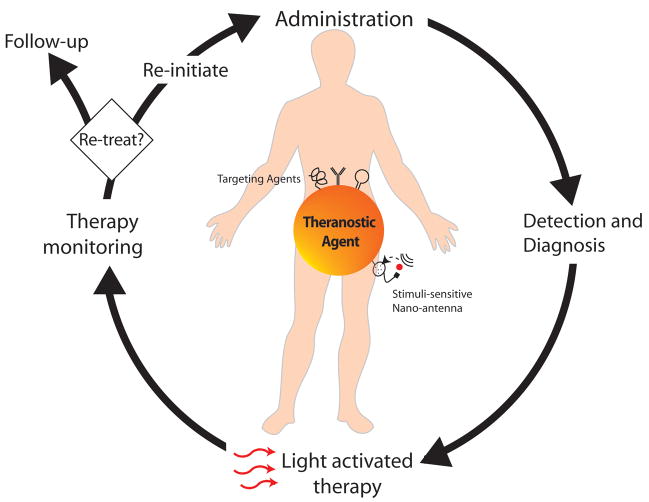

A tool that may help in overcoming this hurdle by successfully integrating therapeutic and diagnostic agents is nanotechnology [9–12]. Application of nanotechnology to medical science has been emerging as a new field of interdisciplinary research among medicine, biology, toxicology, pharmacology, chemistry, material science, engineering, and mathematics, and is expected to bring a major breakthrough to address several unsolved medical issues [9–12]. Nanomedicine – the use of nanotechnology for medicine is starting to make an impact in areas like disease imaging and diagnosis, drug delivery and as reporters of therapeutic efficacy and of disease pathogenesis [9–12]. Many multifunctional nanoparticle (NP) technologies, capable of performing one or more of the above duties, are now in various stages of preclinical and clinical development [9–12]. Theranostic nanomedicine refers to such an integrated nano-platform which can diagnose, deliver targeted therapy and monitor response to therapy. A scheme illustrating the potential role of theranostic agents at various stages of disease management is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Role of photo-triggered theranostic agents at various stages of disease management. Following administration of a single, integrated theranostic agent, a clinician can diagnose disease, detect location of disease, deliver light at the disease locations for activating targeted therapy and following treatment, monitor response to therapy. At this stage, by monitoring the patients response to the therapy, the clinician can decide to either re-initiate treatment or if sufficient regression or cure of disease is observed,call the patient for a follow up visit.

The selectivity and specificity for disease destruction can be enhanced by using externally activatable theranostic agents to produce localized cytotoxicity with little collateral damage. The ability to control drug dosing in terms of quantity, location, and time is a key goal for drug delivery science, as improved control maximizes therapeutic effect while minimizing side effects. Systems responsive to a stimulus such as temperature, pH, applied magnetic or electrical field, ultrasound, light, or enzymatic action have been proposed as triggered delivery systems [13]. Light-triggered theranostics are attracting increasing attention over the past few years due to its advantages in spatial and temporal control of compound release [14]. Recently, light has been used to release therapeutic agents from delivery systems or to activate agents that produce cytotoxic species. In fact, amongst the approved nano-constructs listed by the food and drug administration (FDA), is a light-activatable agent (Visudyne), widely used for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) which is the major cause of blindness amongst the elderly in the developed world. Technological advances in fiber optic fluorescence imaging, a modality which allows investigators to reach into body cavities via minimally invasive endoscopes, have considerably broadened the applications of in vivo optical imaging [15]. This article reviews recent developments in the use of light-triggered theranostic agents for simultaneous imaging and photoactivation of therapeutic agents. The use of lasers and minimally invasive fiber-optic tools, along with the development of new agents that respond to NIR wavelengths for better tissue penetration, make direct targeting of deep tissues possible and thus enabling treatment of several pathologies.

Cancer is one of the most pressing public health concerns of the 21st century. The statistics are daunting; it was projected that 550,000 people would die of cancer and that another 1.4 million would be diagnosed with the disease in 2009 in the United States alone [16]. Another major cause of death, especially in the developing world, are infectious diseases which are making a come-back owing to the problems of drug-resistance and lack of sensitive diagnostic tests [10]. Infectious diseases, caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and other parasites are major causes of death, disability, and social and economic disruption for millions of people. Over 9.5 million people die each year due to infectious diseases – nearly all live in developing countries [10]. Despite the existence of safe and effective interventions, many people lack access to needed preventive and treatment care [10]. Cardiovascular diseases (e.g. atherosclerosis) continue to be the biggest cause of death in the developed world [9]. Taken together, there is a vital un-met need for agents that can be used for simultaneous detection, diagnosis and remotely triggered therapy for selective destruction of diseases tissue.

Photo-triggered theranostic constructs could enable an entirely new category of clinical solutions, which permit early recognition of the disease through the use of contrast agents combined with existing imaging modalities (MRI, optical imaging, ultrasound) followed by the tailored release of the therapeutic agent. Here, we will discuss recent developments in the use of theranostic agents for photodynamic-, photothermal- or photo-triggered chemo-therapy for several diseases including cancer and infectious diseases. Sections 2–4 of this review are focused on the application of light-triggered theranostic agents for cancer while section 5 discusses their use for non-cancer pathologies. Generally, this kind of multifunctional agents will provide information on location of disease; targeted and on demand drug release that will lead to more effective therapies, eliminating the potential for both under and overdosing; the need for fewer administrations; optimal use of the drug in question; and increased patient compliance.

2. Photodynamic therapy and imaging for cancer

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging, externally activatable, treatment modality for various diseases [17]. PDT can be defined as the administration of a non-toxic drug or dye known as a photosensitizer (PS) either systemically, locally, or topically to a patient bearing a lesion, which is frequently, but not always cancer [17]. After a sufficient incubation period with the PS, this lesion is then selectively illuminated with light of appropriate wavelength, which, in the presence of oxygen, leads to the generation of cytotoxic species and consequently to cell death and tissue destruction. PDT is clinically approved for treatment of several diseases including cancer and offers several advantages over conventional chemotherapy by providing additional selectivity through the spatial confinement of light used for PS activation [17]. A wide range of PSs have been evaluated so far and only a few of them have successfully transitioned from bench to bedside applications [17]. PS molecules are inherently fluorescent and this can be used for imaging and locating disease, photodiagnosis, often referred to, somewhat incorrectly, as photodynamic diagnosis (PDD). This approach is becoming of increasing interest for oncological applications. It is based on a higher accumulation of PS in tumors compared to normal tissue and is now being routinely used for diagnosis in bladder cancer [17] and fluorescence-guided resection in surgical procedures [17]. The use of PDT as a cancer therapy is particularly attractive because of its fundamental specificity and selectivity [17]. This is due to the fact that the PS concentrates specifically within the malignant tissue so when the light is directly focused on the lesion, it causes PDT reactive oxygen species (ROS) to be generated resulting in cellular destruction at the region of interest. For this very reason, in recent years, PDT has become the subject of intense investigation as a possible treatment modality for various forms of cancer. Similar to chemotherapy, PDT still requires agents which exhibit selectivity for the target cells. Similar to radiotherapy, the mode of action with PDT involves the use of electromagnetic radiation in order to generate radical species in situ. However, PDT is a much milder approach for cancer treatment than either. The reason for this lies in the combination of the mode of action of the PSs employed and their activation in situ by relatively long wavelength, visible light. Ideal PSs are non-toxic in the absence of activating light. The targeting of the cancer in PDT has a dual nature: the selectivity of the photosensitizing drugs employed and the confinement of the activating light to the tumor site alone. Due to the dual selectivity in PDT the non-tumor tissue largely remains unaffected [17].

Despite the regulatory approvals and the clinical success of PDT in oncology, a limitation of all existing PSs is the lack of high selectivity for target tissue at complex anatomical sites. PSs fluoresce upon light activation, thus enabling online imaging of drug for both image-guided drug delivery and for image guided, active, light dosimetry. Simultaneously combining therapy with imaging would help guide treatments and thus enhance treatment response. PS conjugates and supramolecular delivery platforms can improve PDT selectivity by exploiting cellular and physiological markers of targeted tissue [17]. Overexpression of receptors in cancer and angiogenic endothelial cells allows their targeting by affinity-based moieties for the selective uptake of PS conjugates and encapsulating delivery carriers, while the abnormal tumor neovascularisation induces a specific accumulation of PS nanocarriers by the EPR effect [14]. In addition, polymeric prodrug delivery platforms triggered by the acidic nature of the tumor environment or the expression of proteases can be designed [14]. Promising results obtained with recent systemic theranostic carrier platforms are discussed in the next section. These agents will, in due course, be translated into the clinic for highly efficient and selective PDT protocols.

2.1 Photosensitizers for imaging and PDT

2.1.1 Optical imaging

Optical imaging is a non-ionizing, non-invasive technique whose contrast mechanism is based on the optical properties of the tissue constituents such as absorption, scattering and reflectance. Different microscopic to whole body optical imaging techniques based on absorption, scattering, fluorescence, transmission and reflection properties of tissue constituents are available for various biomedical applications. However the primary limitation of various optical imaging techniques is penetration depth due to strong optical scattering properties of tissue. The use of contrast agents in the optical transparent window of 600–900 nm has alleviated this limitation. A recent review on various biomedical optical imaging techniques illustrates the schematics and principles of the techniques [18].

A summary of the PSs currently being used for clinical or pre-clinical research is shown in Table 1. Most approved PSs are porphyrins, consisting of four pyrrole subunits linked together by four methine bridges. Most commonly used photosensitizing agents among them are a photosensitizer precursor ALA (5-aminolevulinic acid) and derivatives and the sensitizers Verteporfin (benzoporphyrin derivative) and Photofrin (hematoporphyrin derivatives), all of which are effective, FDA-approved PS and are often used in clinical applications for imaging and therapy [19]. ALA or its derivatives are administered either locally or systemically and endogenously converted to protoporphyrin IX, the actual PS. This conversion takes place as part of the mitochondrial heme biosynthetic pathway and in case of cancer cells, the higher activity of enzymes involved in this synthesis pathway may contribute to the observed tumor specificity with this PS [19]. ALA has been extensively explored for image guided PDT and 5-ALA hexylester (Hexvix®) is approved for the diagnosis of bladder cancer [20]. Bogaards et al. showed the use of ALA for image guided brain tumor resection with adjuvant PDT [21]. Another PS which is approved for a broad range of applications is Photofrin, which consists of a mixture of four hematoporphyrin derivatives. Photofrin is approved for the therapy of advanced and early lung cancer, superficial gastric cancer, esophageal adenocarcinoma, cervical cancer and dysplasia, superficial bladder cancer and Barrett’s esophagus [22]. Malignant and premalignant lesions in the lung have been detected using Photofrin fluorescence [23]. Kohno et al. also showed the use of hematoporphyrins for early cancer diagnosis in peripheral blood lymphocytes [24]. ALA and Photofrin, often referred to as first generation PSs, are not ideally suited for the imaging or treatment of deeper tissues because of their low absorption capability at longer wavelengths. For an effective PS it is crucial that the absorption peak matches the so called optical window of the tissue for deeper penetration of the light beam. This window describes a wavelength range from 600–900 nm where the light absorption and scattering of the tissue is lower than at other wavelengths. The absorption of hemoglobin and melanin restrict the lower end of this optical window for PDT. The upper end of the optical window is around 900 nm, due to the energy requirement of the light beam for singlet oxygen generation [19].

Table 1.

Current Approvals and Clinical Trials with a Selection of Photosensitizers. The data on clinical trials was obtained from www.clinicaltrials.gov. For clinical approvals see references [17] [22].

| Photosensitizer | Clinical trials | Approvals |

|---|---|---|

| Foscan, meta-tetra(hydroxyphenyl) chlorin) | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, bile duct carcinoma, head and neck cancer | Palliative head and neck cancer |

| Hexvix, 5-aminolevulinic acid hexyl ester (converted to protoporphyrin IX) | Colorectal cancer, bladder cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasma | Diagnosis of bladder cancer |

| Hypericin and Hypericin derivatives | Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, bladder cancer | |

| Levulan, 5-aminolevulinic acid (converted to protoporphyrin IX) | Bladder cancer, skin cancer, penile cancer, glioma | Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma. |

| Lu-Tex, lutetium texaphyrin | Prostate cancer, non-small cell lung cancer | |

| Metvix, 5-aminolevulinic acid methyl ester (converted to protoporphyrin IX) | Basal cell carcinoma, non-melanoma skin cancer | Actinic keratosis, basal-cell carcinoma. |

| NPe6, mono-L-aspartyl chlorine-e6 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer patients with recurrent liver metastases, glioma | Early lung cancer. |

| Pc4, silicon phthalocyanine | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, skin cancers, pancreatic cancer | |

| Photochlor, Hexyl ether pyropheophorbide-a derivative | Lung carcinoma, basal cell carcinomas, Barrett’s esophagus. | |

| Photofrin, hematoporphyrin derivatives | Intraperitoneal cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, refractory brain tumors, non-small cell lung cancer. | Advanced and early lung cancer, superficial gastric cancer, esophageal adenocarcinoma, cervical cancer and dysplasia, superficial bladder cancer, Barrett’s esophagus. |

| Photolon, chlorin-e6- polyvinylpyrrolidone | Malignant skin and mucosa tumors, myopic maculopathy | |

| Purlytin, tin ethyl etiopurpurin | Skin adenocarcinoma, prostate cancer, breast cancer | |

| Tookad, palladium- bacteriopheophorbide-a | Prostate cancer | |

| Visudyne, benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A | Pancreatic cancer, brain cancer, basal cell carcinoma, brain and central nervous system tumors, melanoma | Age-related macular degeneration |

New PSs have been designed that have higher absorption coefficients in the longer wavelength range. Some of these PS like Tookad®, the palladium complex of bacteriochlorophyll, have expanded the range of usable wavelength to over 800 nm and possess excellent tissue penetration [25]. Tookad has a very high singlet oxygen quantum yield of 0.99 but a very low fluorescence quantum yield, thus limiting the theranostic use of Tookad. An ideal theranostic PS is an agent that has high singlet oxygen quantum yield for therapy and also a reasonably high fluorescence quantum yield for fluorescence detection. These requirements are moderately fulfilled by two PSs Verteporfin (BPD; benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A) and Photochlor (HPPH; pyropheophorbide-alpha-hexyl-ether). With a singlet oxygen quantum yield of 0.76 and a fluorescent quantum yield of 0.05 for the monomer, BPD can be an effective theranostic agent. Another PS which has been receiving increasing attention in the last few years is Hypericin. It is one of the most potent naturally occurring PS and was originally extracted from Hypericum (Saint John’s wort). Various synthetic hypericin derivatives have been synthesized with improved physicochemical properties which can be used for imaging and PDT [26]. Clinical studies have demonstrated the potential of hypericin for diagnosis of bladder cancer [27] as well as oral cancers [28]. Hypericin was successfully tested in clinical trials for actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancer [29]. It has also been evaluated in combination therapy with bevacizumab in a mouse model for bladder cancer and the treatment response was imaged using confocal fluorescence endomicroscopy [30]. Recently, Trivedi et al. reported the preparation of chiral porphyrazine (pz), H2[pz(trans-A2B2)] (247), and its potential for imaging and therapy [31–32]. Pz-247 exhibits NIR-emission and shows preferential uptake into tumor cells. The authors demonstrated the association of Pz-247 with low density lipoproteins (LDL) and it’s receptor-mediated cellular uptake with localization in lysosomes. NIR optical imaging of mice with subcutaneous breast cancer tumors showed a strong contrast between tumor and surrounding normal tissue 48 hours after intravenous (i.v.) injection of Pz-247.

Most of the clinically used PSs show some inherent selectivity for the diseased tissue probably due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. While some additional selectivity of PDT for localized tumors can be achieved by site-specific administration of light using optical fibers, the non-specific uptake of PS by normal tissue is a major problem for PDT of highly disseminated tumors (e.g. ovarian cancers), as this can cause severe collateral damage. PS tumor selectivity can be improved by conjugation of PS with molecular moieties that are known to target cellular receptors, intracellular organelles, or vasculature of diseased tissue. Antibodies have been used as one of the earliest PDT targeting strategies by covalent conjugation of PS to form the photoimmunoconjugates (PIC). Recently, Savellano et al. conjugated BPD to PEGylated cetuximab, a clinically approved monoclonal antibody which binds to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), that is often over-expressed on the surface of epithelial cancers [33]. At an optimal labeling ratio (BPD:cetuximab = 7 or 10 :1), PIC was found to accumulate at significantly higher level on EGFR-overexpressing cancer cells (A431 and OVCAR-5) as compared to the low EGFR expressing fibroblast cells (NR6). Although the phototoxicity was less compared to BPD at the equivalent dose, the authors showed that they can still effectively destroy cancer cells by increasing the light dose.

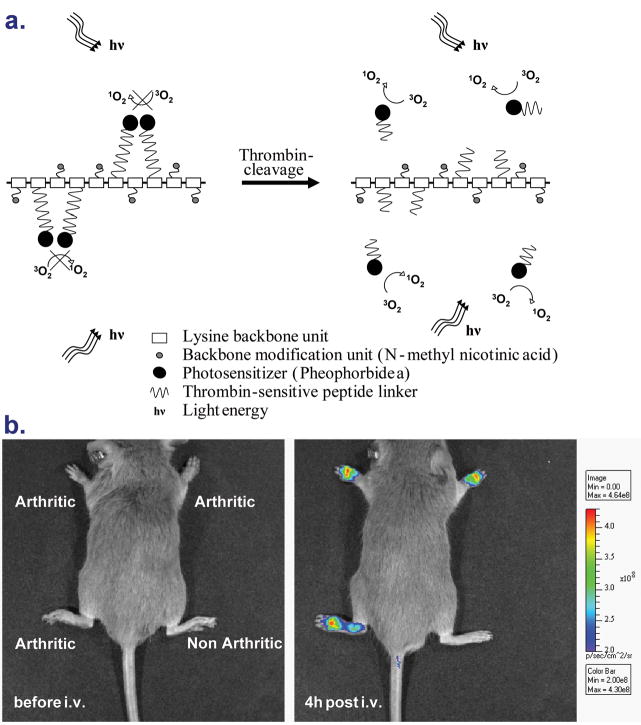

In addition to antibody-based PS conjugates, small molecules and synthetic biomolecules such as RNA-aptamers [34] and peptides have been developed to enhance the delivery to cancer cells. For example, conjugation of pyropheophobide to 2-deoxyglucose resulted in delivery and trapping of PS in cancer cells via the glucose transporter (GLUT)/hexokinase pathway, and therefore is useful both as a near-infrared fluorescence imaging probe and as a PDT agent for the destruction of cancers which has higher levels of GLUT and hexohinase activity than normal tissues [35]. Although, most of the biomolecules were chemically modified to overcome potential degradation by proteases and RNases in vivo, the protease susceptibility of peptides has been explored to design target activatable prodrugs. This approach was initially developed as an imaging technique to differentiate between target and background [36]. A typical construct or “molecular beacon” as it has been referred to, consists of a fluorophore attached to an appropriate fluorescence quencher by a short linker. Cleavage of this linker by some stimulus specific to the target can activate the fluorophore for imaging. This approach has been demonstrated to be well suited for monitoring the target activity [37]. In addition, it has the advantage that one target (e.g., an enzyme) can activate several individual beacon molecules leading to amplification of the fluorescence intensity. This strategy has been shown to elicit a 10 to 1,000 fold amplification of the fluorescence signal compared to simple tagging. This activatable imaging strategy was first introduced for PDT by Zheng et al. in 2004 by replacing the fluorophore with a PS and has been explored for its theranostic potential [38]. Since then, several groups have published promising results and the number of activatable PSs has increased dramatically [39–41]. An in depth review of these activatable PSs was recently published by Lovell et al. [22].

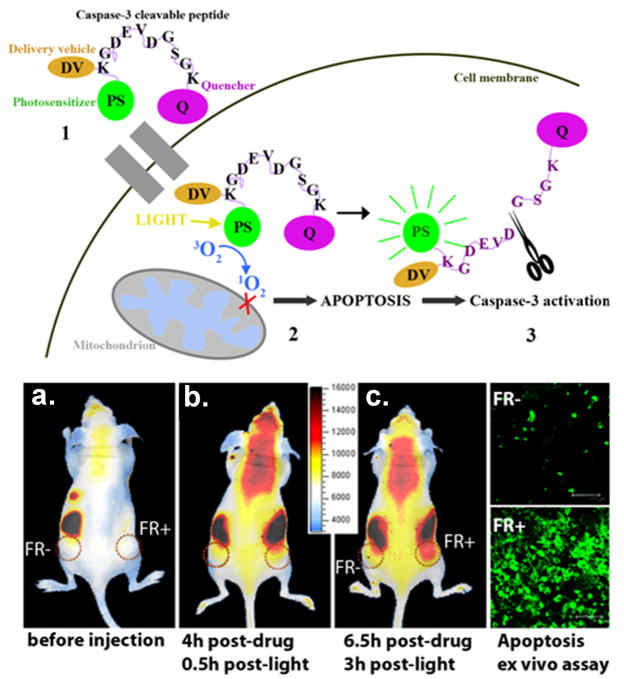

A further development in this field of activatable molecular beacons is the use of a targeting moiety. This targeted molecular beacon strategy was demonstrated by Stefflova et al. [42]. The authors designed a multifunctional, membrane-permeable, and cancer-specific construct that triggers and images apoptosis in cancer cells. This construct contains a fluorescent PS (pyropheophobide) and a cancer-associated folate receptor targeting molecule connected to a caspase-3 cleavable peptide linker that has a fluorescence quencher (BHQ-3) on the opposite side. The double-tumor mouse bearing a folate receptor negative tumor (derived from HT 1080 cells) on one side and a folate receptor positive tumor (derived from KB cells) on the contralateral side was injected intravenously with the construct, followed by PDT. A distinctly higher post-PDT increase in fluorescence was observed in the folate receptor positive tumor compared to the folate receptor negative tumor, confirming the targeting and apoptosis-reporting functions of the construct (Fig. 2). The use of a single molecular agent for targeted PDT and monitoring response to the treatment demonstrated the theranostic potential of such an approach.

Figure 2.

Theranostic molecular beacons for targeted PDT and monitoring treatment response. The top panel is the schematic diagram of structure and function of a targeted PDT agent with a built-in apoptosis sensor: (1) This construct consists of PS, caspase 3 cleavable sequence, fluorescence quencher, and delivery vehicle; (2) The construct accumulates preferentially in cells overexpressing folate receptor, and once activated by light, the PS produces singlet oxygen that destroys the mitochondrial membrane and triggers apoptosis; (3) This leads to activation of caspase 3, which cleaves the peptide linker between the PS and the quencher, thus restoring the PS’s fluorescence and identifying those cells dying by apoptosis by NIR fluorescence imaging. The bottom left panel demonstrated in vivo induction and detection of apoptosis in a mouse bearing folate receptor positive (FR+, KB) cells) and folate receptor negative (FR-, HT 1080 cells) tumors after light treatment (Photodynamic Therapy = PDT, 90 J/cm2) using intravenously administered photoactivatable drug Pyro-K(folate)GDEVDGSGK (BHQ-3) (PFPB, 25 nmol) cleavable by Caspase-3. (a–c): Xenogen images of a mouse bearing FR- (left) and FR+ (right) tumors: a. before i.v. injection of PFPB or PDT; b. 0.5 hour after PDT (4 hours after drug injection); c. 3 hours after PDT (6.5 hours after drug injection). These images are showing a gradual increase in fluorescence in the FR+ compared to FR- tumor. Bottom right: Confocal images of the histology tissue slides of the corresponding FR+ and FR- tumors stained with Apoptag confirmed increased light-induced apoptosis in the FR+ tumor. Adapted from Steffalova et al. [42].

2.1.2 Multimodal imaging (MRI and PET)

Optical fiber-based fluorescence imaging techniques combined with targeting agents have been extensively studied for diagnosis, PDT and treatment response monitoring [17]. However, poor light penetration limits the applicability of light-based imaging and therapies to superficial tumors with depths of 1–2 mm into the tissue. Thus, an emerging trend in the development of theranostic PDT agents is the coupling of optical imaging with other imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound.

PET imaging agents are most commonly labeled with radioisotopes such as 11C (t1/2=20.4 min) and 18F (t1/2=110 min). However, it is very challenging as synthesis, purification and analysis of these short-lived isotopes has to be done within the order of a few minutes. Large isotopes such as 86Y (t1/2=14.7 hours), 64Cu (t1/2=12.7 hours), and 124I (t1/2=4.2 days) are more suitable candidates. Radiolabeling with 124I for PET studies involving PDT is most appropriate because PS needs relatively long time to accumulate in tumors. A simple method to prepare the 124I-labeled PS is the direct electrophilic aromatic iodination of the trimethylstannyl substituted analogues with Na124I in the presence of commercial iodogen beads. Using this strategy, Pandey et al. prepared 124I-labeled pyropheophorbide and purpurinimide analogues with >95% radioactive specificity [43–44]. It was proposed that this radioactive construct could be used for PET and fluorescence imaging as well as PDT.

MRI is a widely used tool in pharmaceutical research due to its excellent soft-tissue contrast property that provides three-dimensional anatomic images with high spatial resolution. Unlike nuclear scanning, conventional radiography or computed tomography, MRI often relies on contrast enhancers to improve inherent contrast between normal and diseased tissue by altering longitudinal (1/T1) and transverse relaxation rates (1/T2) of tissue protons. Agents containing paramagnetic transition metal ions such as gadolinium (Gd+3) and manganese (Mn+2) have been shown to effectively alter 1/T1 and/or 1/T2. Gd+3 in particular, has seven unpaired electrons within the inner orbital shells and provides a high degree of paramagnetism which causes an increase in the T1 relaxation rates of nearby water molecules. Gd+3 is too large to be accommodated in the macrocyclic center of ordinary porphyrins. Incorporation of Gd+3 with a PS can be achieved by two methods: First method is to insert the ion into an expanded porphyrin which contains five (instead of four) nitrogen atoms in the ring, forms a central chelating cavity 20% larger than that of ordinary porphyrins to accommodate Gd+3 [45]. This metal complex, namely Motexafin gadolinium has been proposed for the treatment of brain cancer but was rejected by FDA in 2007. While the lutetium complex of Motexafin was undergoing clinical trials as a PS agent [46], interestingly, Gd+3 analog had only been investigated as a potential radiation sensitizer by causing redox stress to cancer cells. The second method of incorporating Gd+3 with a PS is to stabilize Gd+3 by attaching PS with a side-chain moiety such as diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA). This strategy is more favorable because it can be applied to virtually any PS. In an early study, two Gd-DTPA moieties were covalently linked to mesoporphyrin (Gadophrin-2) and later to the copper complex (Gadophrin-3) for improved stability and safety. Although such metalloporphyrins may be useful for tumor imaging, they were found to preferentially localize in the periphery of necrotic areas rather than the viable cancer tissue [47].

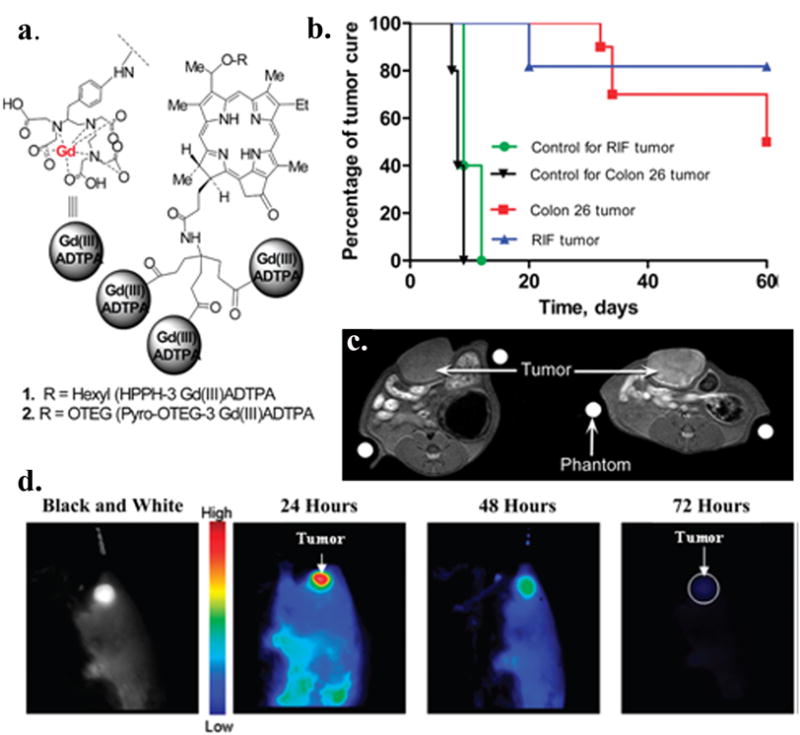

Pandey and co-workers [48–49] investigated the possibility of delivering the contrast agents to living tumor cells by conjugating gadolinium complexes to HPPH, a tumor-avid chlorophyll derivative at Phase II clinical trials. In this study, up to six Gd+3aminobenzyl DTPA complexes were coupled to HPPH. Most of them had enhanced tumor-imaging potential (T1/T2 relaxivity), which increased with larger number of Gd+3 units. To achieve a comparable signal intensity of the clinical MRI agent Gd-DTPA, only a 10 to 20-fold lower dose of the conjugate was required. The three Gd+3aminobenzyl DTPA conjugate, which showed the best PDT activity in vitro was evaluated in vivo. At 24 h post injection, the accumulation of the conjugate in the Ward tumor was higher than in blood, muscle and most organs. At imaging concentration, the required light dose for the conjugate was lower than the one required for HPPH alone, to achieve comparable tumor response in both radiation induced fibroblast (RIF) and Colon 26 tumor models.

Another promising theranostic system has been developed by Liu et al. to enhance the monitoring of PDT efficacy [50]. In this study, the author investigated a novel PS, prepared from fullerene (C60), which combines the property to produce singlet oxygen and can be conjugated to an MRI agent. Gd3+ was selected as the MRI contrast agent and introduced to the PEG terminal of C60-PEG through metal chelation. Following intravenous injection in the tumor-bearing mice, C60-PEG-Gd maintained an enhanced MRI signal at the tumor tissue for a longer time period in comparison with the commercial contrast agent (Magnevist®). The PEG-conjugated fullerene system showed significant tumor PDT effect although the effect depended on the timing of light irradiation.

To study contrast-enhanced MRI guided PDT with PEG bifunctional polymer conjugate containing an MRI contrast agent and a PS, Vaidya et al. have synthesized PEGylated poly-(L-glutamic acid) conjugates containing mesochlorin e6, a PS, and Gd(III)-DO3A [51–52]. MRI images showed that pegylated conjugate had longer blood circulation, lower liver uptake and higher tumor accumulation than the non-pegylated conjugate. Laser irradiation of tumors resulted in higher therapeutic efficacy for the pegylated conjugate. The PDT treated animals showed a reduced vascular permeability with dynamic contrast-enhanced-MRI and reduced microvessel density on histopathological analysis. They concluded that PEGylation of the bifunctional polymer conjugates reduced non-specific liver uptake and increased tumor uptake, resulting in significant tumor contrast enhancement and higher therapeutic efficacy [52].

Ultrasound as a label-free technique has been used in vascular and interventional imaging. Its therapeutic effects in treatment of solid tumors and its efficacy and safety were confirmed in clinical investigations [53]. There have been several reports on the ability of certain porphyrins (sonosensitizers) to enhance the low-intensity ultrasound-induced cytotoxicity, both in cell culture and in tumor model. This treatment modality is named Sonodynamic therapy (SDT). Although the mechanism of this enhancement effect has not yet established, the experimental evidence suggests that sonodynamic effect may due to the chemical activation of sonosensitizers inside or in the close vicinity of hot collapsing cavitation bubbles to form sensitizer-derived free radicals, and/or due to mechanical stress of physical disruption of cellular membrane by sensitizers [54]. It was also reported that the combination of SDT with PDT can induce tumor necrosis more extensively than in mice receiving only SDT or PDT [55].

The use of PSs as imaging agents for diagnosis or fluorescence guided tumor resection is emerging in the last years. PSs were combined with imaging techniques including fluorescence, MRI, PET, and ultrasound. Some of these approaches have already entered clinical trials or are approved like 5-ALA hexyl ester for the diagnosis of bladder cancer in Sweden. Hexvix was recently approved in the US for bladder cancer detection and fluorescence-guided resection. New technologies for molecular targeting will increase the tumor specificity thereby enabling sensitive and specific detection and site specific treatments.

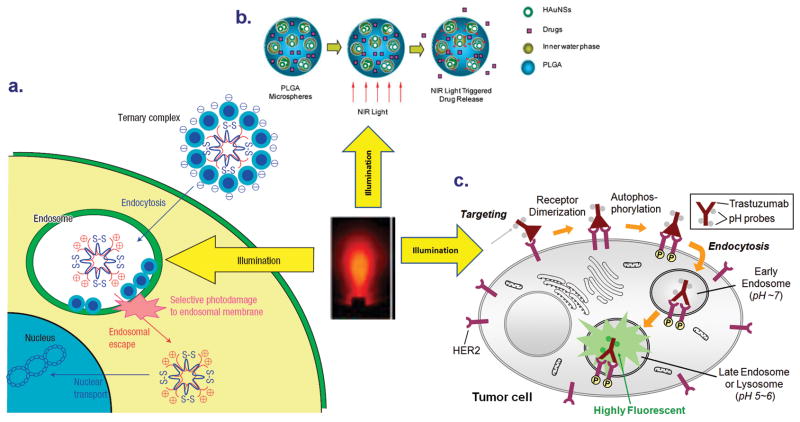

2.2 Nanoparticles for imaging and PDT

Over the last few years, nanoparticle (NP) based PDT has emerged as an alternative to conventional PDT to efficiently target cancer cells. The dual selectivity provided by the target localizing ability of NP and the spatial control of illumination could significantly reduce the systemic toxicity associated with classical PDT therapy. Besides the systemic toxicity, most PSs used in PDT, have other limitations. Mainly, they are hydrophobic or have a limited water solubility and therefore could aggregate in biological media which leads to the modification of their optical properties and the decrease of singlet oxygen production [56]. Although recently a lot of work has focused on developing several new strategies to improve the performance of PDT agents, including conjugation with oligonucleotides, monoclonal antibodies, carrier proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, or hydrophilic polymers for selective delivery of the agents into tumor tissues [57], the lack of specific targets and the dark cytotoxicity is still a principal challenge for PDT. Many efforts are ongoing to develop new conjugated PS with a covalently linked vector to target receptors over-expressed in cancer cells, however very few have been evaluated in clinic mainly because of their lower in vivo selectivity [58].

Nanotechnology provides a platform for integration of multiple functionalities in a single construct [59]. Here we provide an update of simultaneous tumor targeting and imaging with a number of different nanosystems that have the potential for theranostic PDT. Various nanoprobes have been developed for in vivo magnetic resonance and optical imaging, which include quantum dots, upconverting nanophosphors, gold and Silica NPs, PS containing nanoparticulate carriers such as liposomes, ceramic, polymeric. The in vitro and in vivo fate of these systems after administration is discussed. Although several challenges remain before this modality can be adopted in clinic, multifunctional NPs offer a good tool to treat deep tumors efficiently with PDT.

2.2.1 Optical imaging

Recent breakthroughs in the synthesis of mesoporous silica NP (MSNP) with high surface areas and tunable pore diameter (2–10 nm) have led to the design of new delivery systems, where different molecules, such as pharmaceutical drugs or fluorescent imaging agents, could be absorbed into the mesopores and released later into various solutions [60]. Furthermore, some reports on the design of PS based MSNP have been published, among them, Roy et al. have studied a ceramic system based NP with an average diameter of 30 nm. The particularity of this NP is their capacity to optically protect 2-devinyl-2-(1-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide (HPPH) PS resulting in a drug-doped, highly monodispersed, and stable NP in an aqueous system. In vitro imaging study of this system demonstrated active uptake of HPPH-doped NPs into the cytosol of tumor cells and efficient cytotoxicity upon irradiation [61].

To circumvent the problem of the mesoporosity of MSNP and the release of the PS during systemic circulation Prasad’s group has succeeded to covalently incorporate iodobenzylpyropheophorbide PS into a novel nano-formulation named Organicaly Modified Silica NPs (ORMOSIL) [62]. These NPs are were taken up by tumor cells in vitro and demonstrated phototoxic action. Kim et al. reported a promising modality using ORMOSIL system where the photosensitizing unit (energy acceptor) is indirectly excited through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) from the two-photon absorbing dye unit (energy donor [63]. In this study, the authors showed use of nanophotonic tools to produce singlet oxygen and to induce tumor cell death following two-photon PDT. They also demonstrated the potential for co-encapsulation of two drugs to provide contrast in fluorescence images of live tumor cells under two-photon excitation and under near infrared (NIR) light.

More recently Prasad et al. investigated the biological issue raised over the use and safety of ORMOSIL system for diagnosis and therapeutic purposes using different bioimaging modalities including PET, MRI and optical imaging [64]. A NIR PS DY776 was encapsulated in ORMOSIL NP, resulting in a ~20 nm diameter size NIR optical probe. Further the PET imaging probe iodine-124 was conjugated with the NPs, which allow imaging of deep tissue. To study the in vivo clearance of the NPs, animals injected with DY776 conjugated ORMOSIL were imaged daily over a period of 15 days. The results showed accumulation of NPs in liver and spleen over a period of 24 hours, whereas the skin showed a maximum concentration at 72 hours post injection of NPs. Furthermore the clearance studies confirmed that all of the injected ORMOSIL was excreted out of the animal via the hepatobiliary excretion without any sign of organ toxicity [64]. This in vivo bio-imaging, bio-distribution, clearance, and toxicity studies showed that combining this multimodal nano-formulation with PDT, make ORMOSIL NPs an exciting modality for treatment and monitoring.

In a recent report He et al. explored the use of methylene blue-encapsulated silica NPs (MB-PSiNPs) for simultaneous in vivo imaging and PDT [65]. MB-PSiNPs were synthesized with an average diameter of 105 nm. Using a chemical trap, the authors confirmed singlet oxygen production after irradiation. To investigate the biological environment effects on the encapsulated MB, the decreased absorption of leukomethylene blue (LMB) which is the reduced form of MB after contact with enzymes was probed at 660 nm. The results showed that encapsulated MB stayed intact in biological system and PSiNPs prevented the MB from being reduced by enzymes [65]. In vivo monitoring of PDT post irradiation was also performed on subcutaneous-Hela-tumor-xenografted mice. Twelve hours after the injection of MB-PSiNPs, the induced fluorescence was used to guide treatment with 635 nm laser light (500 mW/cm2, 5 min). Following treatment, in vivo imaging was performed using a hyperspectral imaging system to assess treatment response. The tumors treated, with NPs and light irradiation were found to shrink gradually while the control tumors did not show any significant effect [65].

MSNPs have also been designed by Zhang et al. [66]. This multifunctional core-shell NP contains a nonporous dye-doped silica core with an average diameter of ~ 37 nm and a ~ 57 nm of mesoporous silica shell containing PS molecules, hematoporphyrin (HP). These nanocomposites are stable and can be stored for over 1 month at room temperature. The elegance of the bi-functionality of this system is its capacity to act not only as a carrier for the photoactivable drug which is covalently linked to the mesoporous silica shell but also as a nanoreactor to facilitate the photo-oxidation reaction. The author demonstrated that doping of fluorescence dyes into the nonporous core allows for simultaneous PDT and fluorescence imaging in vitro.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) provides a highly polyvalent natural nanoplatform for delivery of various imaging and therapeutic agents to neoplastic cells that over express LDL receptors (LDLR) [67]. Covalent attachment of other ligands to the lysine side chain amino groups could be used to target other receptors [68]. The incorporation of NIR fluorescent probes into LDL showed promising results using optical imaging [69–70]. In addition, Gadolinium based agents could also be attached to LDL to improve tumors detection using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [71]. More recently Song et al. designed a novel naphthalocyanine (Nc)-based PS as a PDT agent to be delivered by a LDL NP [72]. This Nc-LDL NP was prepared by reconstituting the tetra-t-butyl silicon naphthalocyanine bisoleate (SiNcBOA) into LDL lipid core. In vitro results indicated that Nc-LDL NPs are internalized into Hep G2 cells specifically via the LDLR mediated pathway. This preferential uptake of Nc-LDL NPs by tumor tissue was confirmed in vivo by noninvasive optical imaging technique. Human serum albumin (HSA), the most abundant protein in human blood plasma has been used recently as a platform to deliver a photoactivable drug Pheophorbide (Pheo) into tumor for PDT [73]. In vitro studies on Jurkat cells using fluorescence lifetime imaging showed that Pheo-HSA NPs efficiently decomposed in the cellular lysosomes resulting in higher phototoxicity.

Solid lipid NPs (SLN) represent a novel carrier system that have various advantages compared to liposomes and polymeric NPs [74]. Stevens et al. have used this platform to synthesize a folate receptor (FR)-targeted SLN in which hematoporphyrin PS has been encapsulated to target FR-overexpressing tumor cells. In vitro cytotoxicity study of these NPs showed an IC50 of 1.57 μM in human oral epidermal carcinoma cells and non-targeted SLN gave an IC50 of 5.17 μM. The selectivity of FR-targeted NP was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy [75].

Up-converting Phosphor Technology, based on lanthanide-containing, submicrometer-sized, ceramic particles that can absorb infrared light and emit visible light, has been used by Chatterjee et al. to design NPs as transducers for PDT [76–77]. The up-converting NPs investigated in this study are composed of sodium yttrium fluoride (NaYF4) nanocrystals co-doped with the rare earth ions ytterbium (Yb3+) and erbium (Er3+) with a polymeric coat of poly(ethylene imine) (PEI). The PS zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPC) was superficially non-covalently adsorbed to the NPs. The researchers have succeeded in this study to image cellular uptake by fluorescence imaging microscopy of PEI/NaYF4:YB3+, Er3+ NPs, and they found significant cell death following irradiation with NIR laser light. A potential clinical use of these NPs is to image and photodynamically treat cancers situated in deep tissue.

Liposomes represent a valuable carrier and delivery system due to their high loading capacity and their flexibility to accommodate different PS with variable physicochemical properties [78]. The PDT agents could be targeted by modifying the design and the surface chemistry of liposomes. However conventional liposome could give promising results when administered topically. Bendsoe et al. have reported a clinical study using liposomal Meso-tetra(hydroxyphenyl)chlorin (mTHPC) gel formulation for topical application in connection with PDT of non-pigmented skin malignancies [79]. In this study the authors reported that the treated area did not show any swelling or reddening, as is often seen in PDT using topical ALA. Further, no pain during or after treatment were reported. One week after treatment, healing progress was observed in several patients and no complications were registered. Beside the clinical efficiency of this formulation, liposomal NPs could be used as probe to monitor the sensitizer distribution within tumor and surrounding normal skin using fluorescence imaging before, during, and after PDT.

In our group, Zhong et al. have used liposomally encapsulated benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (L-BPD) to image, treat and monitor PDT response in vivo in a mouse model of disseminated ovarian cancer [80]. L-BPD (Visudyne) was originally developed for its application in ophthalmology and is currently approved for the treatment of age related macular degeneration (AMD). Additional details about its use in AMD are discussed in section 5.2 of this review. Visudyne is also currently in clinical trials for treatment of ovarian [81–82] and pancreatic cancer [83]. In the study of Zhong and Celli et al. high-resolution fiber-optic fluorescence imaging was used for the detection of microscopic ovarian cancer and for monitoring PDT treatment response. After administration, L-BPD serves as both an imaging agent and a light-activated therapeutic agent. By comparison with histopathology based method, Zhong et al. showed a sensitivity of 86% for in vivo tumor detection using the microendoscope. The results showed that PDT treated mice exhibit an average decrease of 59% in tumor volumes. The author concluded the potential of the approach used to treat and monitor the treatment outcome [80]. Additional studies are necessary to compare feedback from imaging with long-term outcomes to evaluate the potential of this approach for early reporting following treatment and, by extension, as a tool to aid in rational treatment planning.

Using the same platform Derycke et al. have studied the tumor selective behavior of phthalocyanine tetrasulfonate (AlPcS4) when its applied intravesically in transferrin-conjugated liposomes (Tf-Lip–AlPcS4) [84]. The results reported show an efficacy of the PDT treatment using Tf-Lip-ALPCS4 on AY-27 rat bladder carcinoma cells. The authors concluded that transferrin-mediated liposomal targeting of ALPcS4 drugs is a promising tool for PDT of superficial bladder tumors. Thus the selective accumulation of Tf-Lip–AlPcS4 in bladder transitional-cell carcinoma cells would allow photodiagnosis and fluorescence-guided transurethral resection of lesions with a high sensitivity and specificity. Another liposome based formulation has been developed by Meerovich et al. using hydroxyaluminium tetra-3-phenylthiophthalocyanine (3-(PhS)4-PcAlOH) as a NIR PS. Experiments on mice with solid Ehrlich tumor and subcutaneously transplanted P-388 leukemia revealed high selectivity of accumulation of 3-(PhS)4-PcAlOH in tumors in comparison with normal tissues and high PDT activity. The authors concluded that the high selective accumulation of 3-(PhS)4-PcAlOH in tumor could be used for fluorescent diagnosis [85].

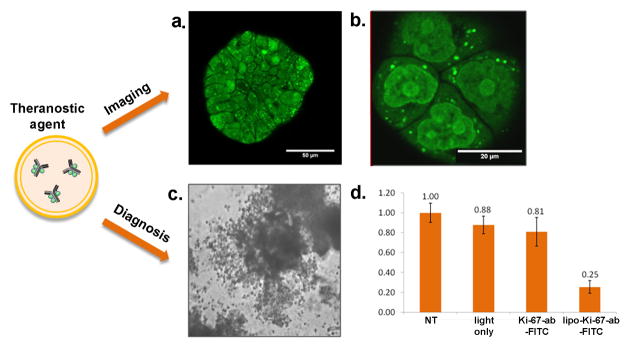

Recently, our group has demonstrated a new approach to target and photoinactivate the nuclear proliferation marker pKi-67 [86]. pKi-67 is a marker that is strongly expressed in all cells that have the ability to divide and proliferate [87]. In many cancers pKi-67 expression is correlated with poor prognosis for disease free progression and overall survival. Therefore, antibodies against pKi-67 are widely used in diagnostics to access the growth fraction of tumors from patient biopsies [88]. Despite the interest of using a diagnostic valuable marker as target for therapy, the inactivation of a nuclear protein has been challenging so far. To target the Ki-67 protein we used dye-labeled antibodies which are encapsulated into PEGylated liposomes (photoimmunoconjugate encapsulated liposomes, PICELS) [86]. The liposomes deliver the photoimmunoconjugate intracellularly where a fraction is released into the cytoplasm. From the cytoplasm the conjugates localize into the nucleus to the actual pKi-67 site. The efficacy of pKi-67 inactivation was demonstrated in a 3D in vitro model for ovarian cancer. In this model ovarian cancer cells form multicellular acini (Fig. 4a), which mimic the small tumor nodules that are found in vivo all over the peritoneal cavity [86]. Treatment of these cells with PICELS and subsequent light irradiation led to destruction of the acinar structure and to more than 70% dead cells 72 h following treatment (Fig. 4b). As a control, pKi-67 negative confluent lung fibroblasts showed no significant effect on cell viability after pKi-67 PDT [86]. In this approach the target protein is not only utilized for the selective delivery of the PS but the antibody itself is inhibiting the protein. Only after light irradiation and the generation of ROS, the photoimmunoconjugate becomes an inhibitor for the target protein. We refer to this as molecularly targeted PDT. The study demonstrated a potential role of pKi-67 as a molecular target for cancer therapy, besides its important role in diagnostics and demonstrated the nuclear delivery of an antibody with non-cationic liposomes [86]. The fact that pKi-67 is a well established marker in tumor diagnostics makes this approach not only valuable for eliminating aggressive cancer cells, it could in the future also be applied to access the growth fraction of the tumor in real time in vivo (Fig. 4a). One or two days after drug administration the fraction of pKi-67 positive cells could be imaged endoscopically in the patient. Different regions in the tissue could be accessed in short time after each other and the Ki-67 labeling index could be estimated based on image fluorescence data. In this first study anti-pKi-67 antibodies were conjugated to FITC (fluorescein 5(6)-isothiocyanate). FITC can easily be conjugated to antibodies and it has been widely used for specific protein inactivation in living cells [89]. FITC has an excitation maximum of 490 nm where light penetration into tissue is fairly limited. For in vivo application a PS with absorption maximum in the longer wavelength range and with higher singlet oxygen quantum yield seems to be more applicable.

Figure 4.

Photoimmunoconjugate encapsulating liposomes (PICELS) for targeting and inactivation of the nuclear proliferation marker pKi-67. a. PICELS deliver pKi-67-FITC antibodies intracellular and can be imaged with confocal microscopy in ovarian cancer 3D-culture ascini. b. Imaging of monolayer cultures shows the nucleolar localization on the PICELS. c.72 hours after laser irradiation with 5 J/cm2 at 488 nm the 3D-acini have lost their spherical morphology and d. Following treatment with PICELS and light irradiation the 3D-acini show a significant decrease in the number of viable cells as measured by a live-dead assay. Based on work by Rahmanzadeh et al. [86].

Numerous reviews have described and provided results on the use of gold NP (GNP) in many biomedical applications including imaging and therapy of cancer [90]. Beside the availability of rich chemistry regarding GNP, currently it is possible to modify the surface of this NP either covalently or noncovalently with PSs. Recently, Wieder et al. reported the development of a new delivery system based on GNPs, whereby the PS is attached to the surface of the NP [91]. Their results showed that GNP conjugates are an excellent carrier for the delivery of hydrophobic PS for high PDT efficacy toward tumor cells. The uptake of these NPs and their phototoxicity toward Hela cells was confirmed using confocal imaging microscope. Though the results are encouraging using these NPs, the PDT efficiency of this system remains to be evaluated in vivo.

Zaruba et al. recently studied the efficacy of PDT using GNP on which two porphyrin–brucine conjugates were immobilized [92]. The intracellular distribution and tumor cell uptake of these NPs were studied using fluorescence microscopy and the results showed that these NPs localize in lysosomes. The in vivo results showed that the brucine-porphyrin derivatives bound to modified GNPs mediate a complete regression of PE/CA-PJ34 carcinoma after PDT. More recently Russell and Jori groups have investigated the in vivo efficacy of Zn(II)-phthalocyanine disulphide (C11Pc) bound to GNPs for the PDT of amelanotic melanoma [93]. In this paper the authors showed an enhanced accumulation of this NP on subcutaneously implanted amelanotic melanoma. Further, electron microscopy observations of tumor specimens obtained at different times after PDT, showed an extensive damage of the blood capillaries and endothelial cells.

Among the various delivery system of GNP, Cheng et al. investigated the efficiency of PEGylated GNP attached to phthalocyanine 4 (Pc4) for in vivo PDT of cancer [94]. A 35% singlet oxygen quantum yield was obtained for Pc4 on PEGylated GNPs while free Pc4 had 50% singlet oxygen quantum yield. Fluorescence images of tumor-bearing mouse were also taken at 1, 30 and 120 min after i.v. injection of drug conjugated NPs. The results showed that the drugs accumulated at the tumor site through a passive targeting process. After illumination the effect of treatment appeared within one week without any noticeable toxicity or side effects to the animals [94].

2.2.2 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Considerable research efforts have been directed towards developing efficient chitosan-based NP drug delivery systems. In comparison to other biological polymers, positive charges target the chitosan carriers to the negatively charged cell membrane and have mucoadhesive properties to prolong the retention time of chitosan in the targeted locations [95]. Magnetic chitosan NPs can provide excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity and water solubility without compromising their magnetic targeting ability [96]. Based on these findings Sun et al. have studied a magnetic targeting chitosan NPs (MTCNPs) which have been prepared and tailored as MRI imaging agents and in which PS - 2,7,12,18-tetramethyl-3,8-di-(1-propoxyethyl)-13,17-bis-(3-hydroxypropyl) porphyrin (PHPP), was encapsulated as photo-activatable agent [97]. The results showed that PHPP-MTCNPs could be used in MRI monitored PDT. Non-toxicity and high PDT efficacy on SW480 carcinoma cells both in vitro and in vivo were achieved with this nano formulation. It is noteworthy that the localization of PHPP-MTCNPs in skin and hepatic tissue was significantly less than in tumor tissue; therefore PDT side-effects could be attenuated using this polymeric NP.

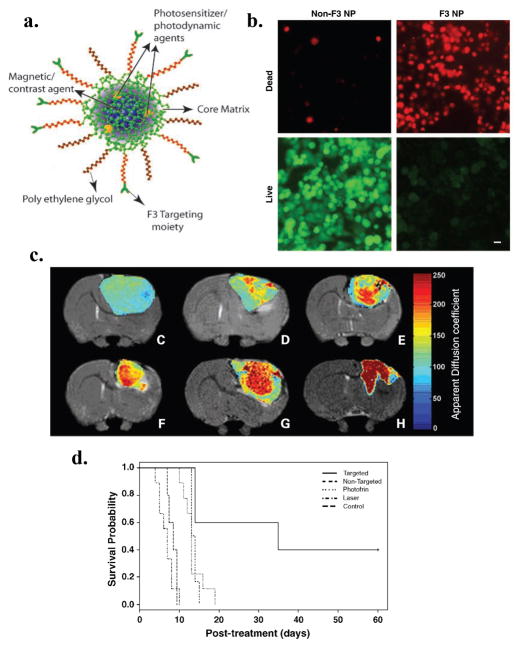

Multifunctional NP (MNP) platforms have been developed by Kopelman and co-workers for in vivo MRI enhancement and PDT of brain cancer [98–100]. The MNPs developed by this group are targeted or enhanced in vivo imaging, diagnostics and therapy. In a recent study by this group, the F3 peptide, which binds to nucleolin expressed on tumor endothelium and cancer cells, was utilized to deliver an imaging agent to brain tumors [100]. The photoactivable agent (Photofrin) and contrast agent (Iron oxide) were encapsulated into amine-functionalized NPs within the core of polyacrylamide matrix. PEG was attached to the surface of the NP along with the targeting peptide (Fig. 5a). After that F3 peptides were conjugated to NP and labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 for optical imaging purpose. To investigate in vitro efficiency of F3 targeted MNP, MDA-MB-435 human breast cancer cells were incubated 4 h with these NPs and irradiated with 630 nm laser light. The resulting combination of light and NPs embedded with Photofrin MNP induced 90% cytotoxicity. Additionally, this study revealed that F3-targeted NPs were bound to, internalized, transported, and concentrated within tumor cell nuclei (Fig. 5b). In vivo studies revealed that iron oxide/Photofrin-encapsulated F3-targeted NPs could be detected in intracranial (i.c.) 9L gliomas using MRI (Fig. 5c). In vivo efficiency of the PDT treatment was monitored after irradiation using T2-weighted and diffusion MRI to follow changes in tumor diffusion for up to 8 days. Based on the correlation of the magnitude of diffusion changes with animal survival [101], F3-targeted NPs were found to have the largest increase in diffusion values and were also found to have the longest survival time over the other treatment groups [100]. The percent of apparent diffusion coefficient showed that there was no statistical difference between the survival of animals treated with Photofrin and those treated with non-targeted Photofrin-encapsulated NP. The T2-weighted MRI image showed an increase of apparent diffusion coefficient 40 days after treatment with the F3-targeted NP, which implied tumor shrinkage. Kaplan-Meier survival plots for the i.c. 9L gliomas tumors showed that PDT based on F3-targeted Photofrin-containing NPs produced a significant improvement in treatment outcome (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5.

Vascular targeted PDT with theranostic agents improves brain cancer therapy as confirmed by MRI a. Schematic representation of the multifunctional nanoparticles. The core of the nanoparticle was synthesized from polyacrylamide, which was embedded with PDT dyes (Photofrin) and/or imaging agents (magnetite/fluorochrome). Polyethylene glycol linker and a molecular address tag (F3 peptide) were attached to target these nanoparticles to cancer cells. b. Cytotoxicity induced by F3-tagged Photofrin-embedded nanoparticles and laser irradiation. MDA-435 cells were incubated 4 hours with nanoparticles with or without F3 tag and irradiated with 1,500 mW of laser for 5 minutes. The Photofrin-mediated cytotoxicity was then monitored by labeling cells with calcein-AM (green, live cells) and propidium iodide (dead, red cells). Bar, 20 μm. c. T2-weighted magnetic resonance images at day 8 after treatment from (C) a representative control i.c. 9L tumor and tumors treated with (D) laser light only, (E) i.v. administration of Photofrin plus laser light, and (F) nontargeted nanoparticles containing Photofrin plus laser light and (G) targeted nanoparticles containing Photofrin plus laser light.The image shown in (H) is from the same tumor shown in (G), which was treated with the F3-targeted nanoparticle preparation but at day 40 after treatment.The color diffusion maps overlaid on top ofT2-weighted images represent the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) distribution in each tumor slice shown. d. Kaplan-Meier survival plot for the i.c. 9L tumor groups. Survival curves for brain tumor animals: untreated, laser only, i.v. Photofrin + laser treated, nontargeted nanoparticles containing Photofrin + laser, and F3-targeted Photofrin-containing nanoparticles + laser treated. Adapted from Reddy et al. [100].

In a recent study by our group, L-BPD was used as a PDT agent and Magnevist was used as a MRI agent to monitor tumor development and therapeutic response to PDT in pancreatic cancer xenograft models [102]. To determine pretreatment tumor volume and tumor vascular perfusion volume, MRI images were obtained at 24 to 48 hours pre-PDT and at 48 hours post-PDT. Two tumors cell lines (AsPC-1 and Panc-1) were investigated in this study because of their different levels of aggression. The in vivo and ex vivo data showed that the more aggressive AsPC-1 tumors showed a better response to PDT than the less aggressive Panc-1 tumor. Ex vivo fluorescence image and histological images (H&E stain) were used to assess collateral damage caused by PDT and the results correlate with the in vivo MRI images [102].

Recently Lai et al. have designed and synthesized a tri-functional NP using heavy-transition-metal complexes instead of organic sensitizer [103]. In this study the authors demonstrated that Fe3O4/SiO2 core/shell nanocomposites conjugated by a functionalized iridium complex allow in the same nano-construct the possibility of MRI, phosphorescent labeling and simultaneous singlet oxygen production. The resulting Fe3O4/SiO2(Ir) NP with 55 nm diameter size showed a 62% fluorescence and ~ 10 % phosphorescence quantum yield. In vitro cellular uptake of these nanocomposites were confirmed by MRI. A new class of MSNP was also fabricated by covalent attachment of a PS and by covering their external surface with mannose residues. It was demonstrated in this study that these MSNPs showed a greater in vitro PDT efficiency in MDA-MB-231 cancer cells [104]. The same group also successfully developed a new approach to synthesize multifunctional NPs by using covalent attachment of cyano-bridged coordination polymer Ni2+/[Fe(CN)6]3− to the surface of two-photon dye-doped MSNPs. These hybrid NPs combine effective two-photon excited fluorescence, porosity, high MRI efficiency and superparamagnetic properties [105].

Quantum dots (QD) have gained enormous attention for bio-sensing and bio-monitoring applications. The new generation of QDs have demonstrated promising potential in various applications such as the study of intracellular processes at the single-molecule level, high-resolution cellular imaging, long-term in vivo observation of cell trafficking, tumor targeting, and diagnostics [106]. Bakalova et al. highlighted the potential capacity of QD as candidates for application in PDT and the possibility to conjugate them with appropriate classic PS to increase photosensitizing efficiency [107]. Further, it was also reported that cadmium selenide (CdSe) QD can be used to sensitize a PDT agent via energy transfer mechanism [108]. Recently Bakalova et al. presented a study in which they describe a multimodal QD probe with combined fluorescent and paramagnetic properties, based on silica-shelled single QD micelles with incorporated paramagnetic substances [tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionate)/gadolinium] into the micelle and/or silica coat [109]. The results showed that the developed QD probe is appropriate for in vitro and in vivo tracking of cells and blood vessels via simultaneous use of fluorescent microscopy and MRI.

Tremendous progress of NP-based theranostic PDT has been made in the last few years. Although the majority of researchers are concentrating on developing new formulations and conjugated nano-platforms to enhance selectivity and efficacy, the treatment of deep-seated solid tumors is still a challenge that needs more attention. Recently Cheng et al. have designed a novel PDT agent in which the light is generated by X-ray scintillation of NPs attached with PS [110]. The hypothesis is that the photoactivable agent could be excited without the use of external light source. When the NP-PS conjugates are targeted to tumors and stimulated by X-rays y, the particles generate visible light that can activate the PS for PDT. In this self-lighting PDT regime tumor destruction can be more efficient due to simultaneous PDT and radiotherapy. More importantly, it can be used for deep tumor treatment as X-rays can penetrate deeper through tissue. Further, conjugating this NP with targeting agents could enhance PDT selectivity. Recently this group has reported the synthesis of LaF3:Tb3+–meso-tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphine (MTCP) NP targeted conjugates and investigated the energy transfer as well as singlet oxygen generation following X-ray irradiation [111]. The results showed that LaF3:Tb3+-MTCP NP conjugates are efficient photodynamic agents that can be initiated by X-rays at a reasonably low dose. The addition of folic acid to facilitate targeting to folate receptors on tumor cells has no effect on the quantum yield of singlet oxygen production in the NP-MTCP conjugates. The elegance of this novel modality is that it needs lower doses of radiation to produce singlet oxygen and could be used in medical imaging to diagnose diseases.

3. Photothermal therapy and imaging for cancer

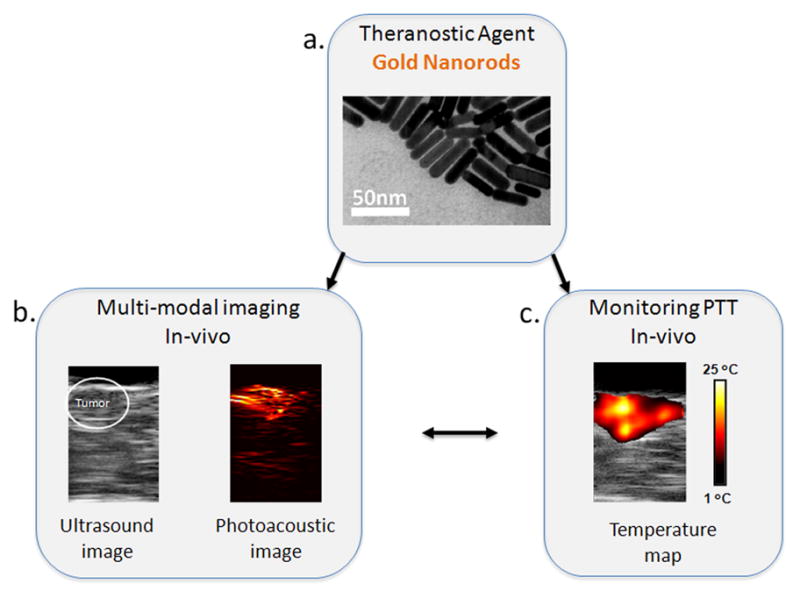

Photothermal therapy (PTT) is a treatment regime involving irradiation of diseased tissue with electromagnetic radiation (VIS-NIR light) to cause thermal damage. Unlike PDT where ROS are generated by excitation of a PS, in PTT the laser energy is absorbed by the photo-absorbers and is converted to heat. PTT can cause biological changes ranging from protein structural changes to carbonization of the tissue. During PTT the temperature rises to anywhere between 45 °C to 300 °C and the therapeutic effects can be obtained at sufficient depths using NIR radiation. PTT like PDT brings additional specificity to the therapeutic technique as only the diseased tissue is irradiated with light while the surrounding benign tissue is minimally damaged. This spatial specificity and the minimal-invasiveness make PTT an attractive therapeutic modality as compared to open surgery or other invasive therapeutic procedures. In PTT either continuous wave or pulsed lasers are used for tissue irradiation. In case of continuous wave lasers, sufficient laser energy needs to be deposited in the target area before heat loss occurs in the tissue due to blood perfusion. With pulsed lasers, intense heat is built up during PTT as the pulse width used is shorter than the thermal relaxation time of the tissue (thermal confinement condition) [112]. In either case, the laser parameters need to be chosen appropriately to obtain effective thermal therapeutic response. In addition, the laser illumination needs to be chosen at a wavelength where the diseased tissue has higher absorbance than the surrounding tissue i.e., presence of more endogenous chromophores such as hemoglobin and melanin or specific accumulation of photo-absorbers such as NIR dyes in the diseased tissue. Several non-photosensitizing dyes have been introduced to increase the spatial specificity of PTT [113]. Most of these dyes have absorption greater than 600 nm enabling the treatment of deeply situated pathologies. Moreover, as in the case of PDT, the dyes have higher optical absorbance in the “photothermal-therapeutic” window between 600–1000 nm, a range in which the absorption of endogenous chromophores is low. For example, indocyanine-green (ICG) based PTT was used to treat acne vulgaris and the treatment showed significant improvement in 80% of the patients [114]. Similar to PDT photosensitizers, photobleaching of dye molecules is a major limitation in PTT. The advent of non-photobleaching plasmonic metal NPs has enhanced the photodiagnostic and phototherapeutic strategies used for detection and treatment of tumors and infections due to their unique photophysical properties. Especially the development of gold nanoshells by Halas group has further enhanced the efficacy of PTT due to NIR absorption properties of nanoshells [115]. El-sayed et al. have shown the use of gold nanorods for effective treatment of cancer cells [116]. Plasmonic GNPs are excellent PTT agents as they have three to five orders of magnitude higher absorbance than endogenous chromophores and NIR dyes. Moreover, the optical properties of GNPs can be modified by varying their shape, size, coating etc. The rapid heating of non-photobleaching plasmonic NPs has also lead to reduction in treatment time of PTT.

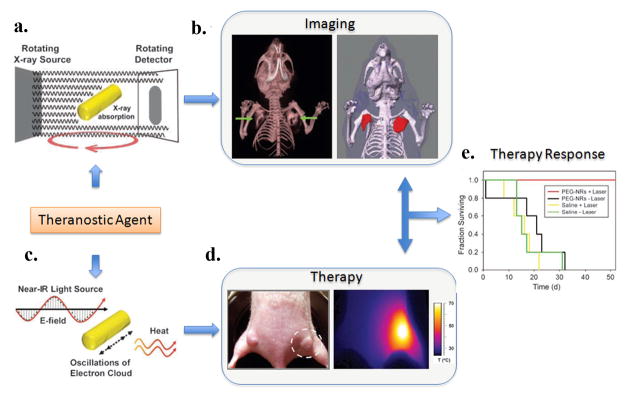

Image guided PTT procedure will enhance therapeutic outcome especially in cancer diagnosis and therapy because 1. Imaging will aid in identifying the precise location of the tumor, 2. Guide and monitor spatial and temporal changes in temperature and tissue morphology during therapeutic procedures and 3. Evaluate the response of the tumor to therapy immediately after therapy procedure and 4. Evaluate the patients for resurgence of the tumors after the therapeutic procedures. A theranostic agent has the potential to be used in one or more of the steps listed above in image guided PTT. Specifically in this section we will review PTT agents that enhance contrast in various imaging modalities such as optical, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and ionizing imaging modalities such as X-ray.

3.1 Optical imaging

PTT agents such as NPs and dyes exhibit intense and narrow optical extinction bands making them ideal contrast agents for optical imaging. Indeed the combination of PTT with various optical imaging modalities is seamless. For example ICG is used for fluorescence imaging as well as PTT. However ICG has short lifetime and is rapidly cleared from the body. To increase the uptake of ICG in tumor location Yu et al. encapsulated ICG in 120-nm polyallylamine capsules [117]. In vitro studies with confocal fluorescence imaging were performed to evaluate the phototherapeutic response of the ICG nanocapsules. A recent review by Jiang et al. featured various fluorescent NPs that were used simultaneously for optical imaging and cancer therapy [118].

In vitro demonstration of the PTT efficacy using various gold based theranostic agents such as nanospheres [119–121], nanoshells [122], nanorods [116], nanocages [123] and nanocubes [124] was performed using traditional optical microscopy techniques such as darkfield imaging, confocal fluorescence imaging etc. Hybrid nanosystems such as silver-gold dendrites [125] and supramolecularly assembled gold nanospheres [126] also show NIR theranostic properties. Novel imaging techniques such as two photon imaging [127] and photothermal imaging [119] have also been used to image cells in conjunction with PTT. One of the first successful in vivo demonstrations for combined optical imaging and PTT using plasmonic NPs was shown by Gobin et al. [128]. Specifically NIR absorbing gold nanoshells were used as dual function theranostic agent for both imaging and cancer therapy. Optical coherence tomorgraphy (OCT), a methodology based on optical backscattering of tissue constituents, was used to monitor uptake of nanoshells in the tumor. Gold nanoshells enhanced the scattering signal for OCT imaging while retaining their photothermal properties i.e., the GNPs can be molded to have high absorption and scattering properties. The results of their therapeutic study showed approximately 40% increase in survival rate in mice that underwent PTT therapy using gold nanoshells as compared to the control study groups. In another in vivo mouse study by Dickerson et al. showcased the potential curative and adjunctive applications of NIR plasmonic gold nanorods [129]. Subcutaneous squamous cell carcinoma xenografts were grown in nude (nu/nu) mice and particles were selectively delivered to tumors by both direct and intravenous injection. In vivo imaging of PEGylated gold nanorod accumulation was monitored by attenuation of NIR transmission at 808 nm using a custom-built CCD device array. PTT was performed with continuous wave laser (0.9–1.1 W/cm2, 6 mm dia., 10 min). The results of the study showed approximately 5 fold decrease in tumor volume as compared to control mice injected with saline solution.

In addition to plasmonic metal NPs and NIR dyes, nanosystems such as carbon nanotubes (CNT) have also been used as theranostic agents. Recently Zhou et al. reported an in vivo photothermal study using single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) tagged with fluorescently labeled folate antibody as theranostic agents [130]. SWNTs have a high optical absorbance in the NIR region (optical absorption peak at 980 nm) and the results of the study showed the potential of SWNTs combined with suitable tumor markers for selective photothermal cancer treatment. Torti et al. showed the feasibility of using multi-walled carbon nanotubes on cancer cells [131]. Overall, as existing optical probes and new optical in vivo imaging techniques make their way to the clinic in the next few years after through characterization, it will not be uncommon to see routine clinical procedures that incorporate such theranostic probes for cancer diagnosis and therapy.

3.2 Ultrasound-based imaging

Ultrasound imaging is an appealing modality for temperature monitoring during PTT as it is a relatively inexpensive, noninvasive and portable imaging technique. Ultrasound has also been used by Emelianov and coworkers to guide and monitor PTT with GNPs as it has the ability to track spatial and temporal changes in temperature increase throughout the region of interest [132]. During these processes, the elasticity of the tissue is also affected which can be evaluated with ultrasound based elasticity imaging [133]. Recently another study from the same group showed the progression of photothermal treatment by quantifying the mechanical properties of tissue using a novel ultrasound based technique namely magneto-motive ultrasound [134]. Therefore, a comprehensive guidance and assessment of the PTT may be feasible through various ultrasound based imaging techniques [135].

Photoacoustic imaging (optoacoustic or thermoacoustic imaging) is an ultrasound based imaging modality with inherent advantage of high contrast optical imaging techniques. More specifically, it provides information on the optical absorption properties of tissue at spatial resolution on par with ultrasound imaging [136–138]. Photoacoustic transients are generated when nanosecond duration laser pulses interact with the tissue causing thermoelastic expansion. The generated pressure wave is detected by an ultrasound transducer and is digitally processed to obtain a photoacoustic image. Thus, by analyzing photoacoustic images captured at multiple wavelengths, the distribution of optical absorption properties of the tissues can be visualized. Optical backscattering from the tissue limits the penetration depth in optical imaging techniques unlike photoacoustic imaging that is only limited by the penetration of light into tissue. Therefore, photoacoustic technique can image deeper since sound is detected instead of light. In addition, greater penetration depth in tissue can be achieved using NIR wavelengths because endogenous chromophores such as blood absorb less light in the NIR range. The availability of various NPs systems (carbon nanotubes, ICG pebbles, different shapes of gold or silver NPs) that have three to five orders of higher optical absorption has increased the potential of molecular photoacoustic imaging for cancer diagnostics. Many groups have published studies on NP enhanced molecular photoacoustic imaging, however only few of them reported the combination of photoacoustic imaging with PTT. The optical properties of photoacoustic contrast agents such as GNPs also entail them to be good therapeutic agents, given the photothermal stability of NPs. For example, Yun-sheng et al. have shown coating silica gold nanorods increased their thermal stability as compared to PEGylated or CTAB coated nanorods [139].

Combined ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging can be used to plan, guide and monitor the outcome of the PTT. In this approach, combined imaging is first used prior to surgery to identify size, location and functional activity (uptake of the optical contrast agent) of the tumor. Then the ultrasound images obtained during therapy are used to generate temperature maps of the tissue using speckle tracking algorithms. In addition to ultrasound measurements of the temperature, photoacoustic imaging can be used to monitor the temperature changes. The efficacy of using gold nanorods simultaneously as photoacoustic contrast agents and phototherapeutic agents is demonstrated by Shah et al. Gold nanorods (GNR) (Fig. 6a) were directly injected into the subcutaneous tumor in nude mice prior to performing PTT. In vivo ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging performed after the injection showed the presence of NPs in the tumor which was later confirmed by silver staining of tissue slices (Fig. 6b). Photoacoustic thermal imaging performed showed significant temperature elevations within the tumor in response to laser irradiation suggesting thermal damage (Fig. 6c). In addition, tumor necrosis was confirmed by histological assessment [135].

Figure 6.

Gold nanorods, a theranostic agent, used for combined ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy. a. the TEM images of gold nanorods. b. Ultrasound and photoacoustic images of mouse tumor injected with gold nanorods. The tumor region is shown in white inset in the ultrasound image. The photoacoustic image shows higher contrast in the tumor area due to accumulation of gold nanorods. c. Thermal image of a subcutaneous tumor in nude mouse. During the PTT procedure approximately 25°C temperature rise was observed in the tumor. Adapted from Mallidi et al. [135].