Abstract

Computer models of microtubule dynamics have provided the basis for many of the theories on the cellular mechanics of the microtubules, their polymerization kinetics, and the diffusion of tubulin and tau. In the three dimensional model presented here, we include the effects of tau concentration and the hydrolysis of GTP-tubulin to GDP-tubulin and observe the emergence of microtubule dynamic instability. This integrated approach simulates the essential physics of microtubule dynamics in a cellular environment. The model captures the structure of the microtubules as they undergo steady state dynamic instabilities in this simplified geometry, and also yields the average number, length, and cap size of the microtubules. The model achieves realistic geometries and simulates cellular structures found in degenerating neurons in disease states such as Alzheimer disease. Further, this model can be used to simulate microtubule changes following the addition of antimitotic drugs which have recently attracted attention as chemotherapeutic agents.

Keywords: cytoskeleton, kinetics, microtubule, model, tau phosphorylation

Introduction

Microtubules exhibit fascinating dynamic behavior and cycle through stages of gradual polymerization and rapid depolymerization (Kristofferson et al., 1986; Mitchison and Kirschner, 1984). This dynamic instability is vital to cellular function as it enables microtubules to occupy, or visit, a greater volume of the cell interior (Holy and Leibler, 1994). Microtubule dynamics are critical to intracellular transport and cell motility, and their dysfunction can play a significant role in cellular degeneration and, ultimately, necrotic cell death. Microtubules are formed and stabilized by the polymerization of tubulin and the binding of a variety of microtubule associated proteins, including tau. In addition, posttranslational modification of tubulin, including acetylation, glutamylation, glycation, phosphorylation and tyrosination, could also affect microtubule function (Perez et al., 2009; Smith et al., 1997; Smith et al., 1994). In Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neurons, the hyperphosphorylation of tau results in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles thus depleting stores of available tau, the major microtubule stabilizing protein for neurons (Buee et al., 2000; Gallo, 2007; Li et al., 2007; Marx, 2007). Microtubules are significantly reduced in number and length in AD neurons, but not in other cell types in the brain (Cash et al., 2003). As a result, microtubule dynamics are thought to be severely compromised, resulting in the demise of neurons following severe loss of function However, antimitotic drugs, which cap microtubules and block microtubule polymerization, have proven to be effective in the fight against cancer (Jordan and Wilson, 2004) and have been suggested as therapeutics for AD (Trojanowski et al., 2005).

Computer simulations have proven to be an invaluable resource in elucidating the physics of microtubules. For example, Holy and Leibler used computer simulations to demonstrate the importance of dynamic instability for spatially sampling the cell interior (Holy and Leibler, 1994). More recently, Daymier et al. used computer simulations to show that tubulin diffusion can have a profound effect on microtubule morphology, which is difficult to investigate experimentally, where the effects of diffusion cannot simply be ‘turned off’ (Deymier et al., 2005). However, the inherent complexities of cellular systems require models of increasing sophistication to encompass the wealth of phenomena observed experimentally.

Mathematical models, which can describe microtubules using a mean-field approximation without describing individual chains, have successfully expanded our knowledge of the basic science of microtubule dynamic instability (Chen and Hill, 1987; Flyvbjerg et al., 1994; Hill, 1984; Rezania and Tuszynski, 2008; Sept et al., 1999). Furthermore, such models are conceptually simple and can be intuitively important when describing microtubules with a minimum number of parameters. A mathematical model has been used to describe the effects of an antimitotic drug on microtubule dynamics (Mishra et al., 2005).

Structural models which simulate the interactions between protofilaments within the microtubule lattice are important for understanding the structure and biochemistry of individual microtubules (VanBuren et al., 2005). While these models are computationally limited in simulating the large length and time scales relevant to cellular activity, they play an important role in our basic understanding of microtubules. Furthermore, models of microtubule structure will likely serve as the starting point for more coarse-grained models in future multi-scale approaches.

Monte Carlo event-based approaches have emerged as a popular method for simulating a wide range of stochastic processes, including microtubule dynamics. For example, Vorobjev and Maly simulated microtubule dynamics using a two-dimensional model, which successfully predicted experimental data (Vorobjev and Maly, 2008). Shpil’man and Nadezhdina used a stochastic approach to imitate the microtubule dynamics observed in a cell (Shpil’man and Nadezhdina, 2006). As mentioned earlier, Deymier et al. simulated individual microtubules interacting with a diffusing tubulin concentration (Deymier et al., 2005). Individual microtubules can be simulated within a cell and these models can correctly mimic the interactions between microtubules and their environment. Such approaches, which model the microtubules discretely, are more suited to simulating highly heterogeneous and complex systems that are representative of the cellular environment.

Taking into consideration such stochastic methods, we developed a discrete model which describes the mechanics and kinetics of individual microtubules, while at the same time modeling the diffusion of tubulin and tau concentrations. While the presented model represents simple geometry, a spherical cell containing an impenetrable nucleus, it is worth noting that this approach can easily be extended to more heterogeneous systems. However, even in the simple geometries considered here, our model captures the physics of microtubule dynamics and yields interesting insights into dynamic instabilities.

The model is presented in three parts: i) the mechanical aspects, ii) the polymerization kinetics, and iii) the diffusion of tubulin and tau, investigating the effects of varying tubulin and tau concentrations.

Experimental Procedure/Model

Novel computer simulations were developed to probe the dynamics of microtubules in a simplified environment. Specifically, the ‘cell’ is considered as a spherical domain (radius of 25 μm) and the nucleus, which occupies 10% of the cell volume, is situated in the center of the cell. Microtubule organizing centers are located near the nucleus and the cells are modeled having either a single center or two centers situated on opposite sides of the nucleus. Microtubules are stochastically nucleated at these sites at an experimentally determined rate that varies with cell cycle progression. Furthermore, the microtubules exhibit dynamic instability as a consequence of stochastic polymerization kinetics and the internal hydrolysis of the GTP contained in the tubulin to GDP. The microtubules are also allowed to move dynamically within the cell environment and, for example, as a growing microtubule interacts with the cellular membrane the microtubule may become elastically deformed. Another important physical process, which is relevant to microtubule dynamics, is the diffusion of tubulin and tau. These regional concentrations play an important role in the local polymerization kinetics. Therefore, in order to capture the physics of microtubule dynamics in a cell it is necessary to combine models of microtubule mechanics, polymerization kinetics, and the diffusion of tubulin and tau. See online supplemental material for animated depiction of the model.

Mechanics

The mechanics of microtubules can be described using linear elasticity theory (Cosentino Lagomarsino et al., 2007). In particular, the elastic free energy of a microtubule is of the form (Landau and Lifschitz, 1986)

where E is the Young’s modulus, u is the displacement along the backbone of the microtubule, and the integration extends over this backbone. R is the radius of curvature, is the moment of inertia and is the cross-sectional area of the microtubule.

The microtubule is discretized into a series of points along the microtubule backbone and the elasticity is captured through the interactions between these points. In particular, the stretching force (in the x-direction) on the ith node due to the (i ± 1)th sequential node is given by

where Δx is the spatial discretization, ri is the position (and ri,x is the position in the x-direction) of the ith node and the superscript o indicates the undeformed positions.

The radius of curvature at ri depends on the positions of the neighboring nodes and can be written as the inverse of the second derivative of displacements orthogonal to the microtubule backbone (Landau and Lifschitz, 1986). The energy associated with the radius of curvature at the ith node contributes the following forces (in the x-direction) to the microtubule

where t indicates the relative position along a line from ri-1 to ri+1 which is closest to ri. Forces in the y- and z-directions are of equivalent form. In this manner the elastic forces acting on the microtubule can be obtained from the discretized positions.

The cell membrane is included as a soft repulsive interaction of the form

where Ro dictates the strength of the repulsion, rcell = 25 μm is the radius of the cell and α = 1 μm controls the lengthscale (or softness) of the repulsion.

The relaxation dynamics of the microtubule are described by the following evolution equation

where ξ is the friction coefficient, F is the local force acting upon a microtubule node, and R is a Gaussian noise satisfying 〈R(t)R(0) 〉 = 2ξkTδ (t) (Coffey et al., 1996). The friction coefficient is given by the Lamb equation, where γ is the Euler constant and Re the Reynolds number (taken to be ≪ 1) (Lamb, 1993).

Polymerization kinetics

To capture the physics of microtubule dynamics, we have to describe the various dynamic events in the system. In particular, microtubules are nucleated by non-tubulin structures (cytoplasmic microtubule organizing centers), they can polymerize (local concentration of tubulin permitting) and also depolymerize (sometimes catastrophically) through the hydrolysis of GTP-tubulin in the microtubules to GDP-tubulin that drastically affects the polymerization kinetics. Microtubules are nucleated at a given nucleation site with a rate of knew = 0.16 s−1 (Piehl et al., 2004). The GTP-tubulin is converted in the wall of microtubules into GDP-tubulin with a rate of khydro = 0.04 s−1. The polymerization kinetics of a microtubule depends on the local tubulin and tau concentrations and, if the end of the microtubule consists of a GTP-tubulin cap, is taken to be of the form

where kpoly0 = 0.004 s−1 μM−1 and kpoly,τ = 0.01 s−1 μM−2 (Drechsel et al., 1992). However, if the GTP-tubulin at the end of the microtubule hydrolyzes to GDP-tubulin, then the rate of polymerization is taken to be zero. Similarly, we assume the depolymerization rate, kdepoly, is 0.7 s−1, if the end of the microtubule consists of GDP-tubulin, but is zero if it is a cap of GTP-tubulin (Erickson and O’Brien, 1992).

Once we have the rates associated with all of the possible events within the system we define an average time over which at least one of these events is likely to occur. In particular, the time step is taken to be the inverse of the sum over all rates (Buxton and Balazs, 2004).

This time step can then be used in the evolutionary equations and dictates the timescale of the simulation. Assuming that during this time an event occurs somewhere in the system, the probability of a particular event occurring is the rate associated with this event relative to the total rate (associated with all events)

where, again, the summation is over all events (Buxton and Balazs, 2004). An event is chosen to occur from the cumulative distribution function associated with these probabilities and, therefore, the selection of an event takes into consideration the correct probability weightings. The cumulative distribution function is defined as

In order to select an event which will occur during this time step, a random number between 0 and 1 is chosen (RND[0,1]) and the ith event is found for which Ci < RND[0,1] < Ci+1. In this manner, the polymerization kinetics of the microtubule dynamics occur stochastically but with the correct probability weightings. Furthermore, a timescale is then associated with these events which can be used to update the microtubule mechanics or the diffusion equation (described in the following section).

Upon polymerization a new region of GTP-tubulin (node) is added to the microtubule backbone with a position

where rn+1 is the position of the new node, r0 = 0.5 μm is the spatial discretization of the filament and δ is a spherically symmetric random vector whose magnitude is chosen to coincide with the persistence length of microtubules where diffusion is likely important. In particular, the orientational correlation function, , where k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and Δ is the energy required to polymerize the microtubule (Rezania and Tuszynski, 2008).

However, not only do the polymerization rates depend on the local concentrations, but the local concentrations are locally increased or decreased in response to the depolymerization or polymerization of a microtubule. In particular, the concentration of tubulin associated with 0.5 μm of a microtubule is 11.6 μM and the amount of tau is taken to be 0.5 μM (Makrides et al., 2003). Therefore, the average concentration of tubulin and tau in the cell varies depending on the number and average length of the microtubules. The local concentrations could also play a role in microtubule dynamics and, for example, a depolymerizing microtubule could leave behind a trail of higher tubulin and tau concentrations, only being counteracted by diffusion, which might encourage polymerization along this trail.

Diffusion

Upon polymerization, local tubulin concentrations are reduced by 11.6 μM (assuming 1750 dimers per micrometer). If enough tau is present the tau concentration is also reduced by 0.5 μM and this value is stored so that the same amount can be added to the local concentration upon depolymerization. The local concentrations of tubulin and tau are allowed to diffuse, given the time obtained from our model of microtubule dynamics, and the spatial resolution of the underlying grid. In other words, we solve the diffusion equations

where Dtub = 0.5 μm2 s−1 is the diffusion coefficient of tubulin (Vorobjev et al., 1999) and Dtau = 3 μm2 s−1 is the diffusion coefficient of tau (Konzack et al., 2007). We assign no-flux boundary conditions at the boundary of our spherical domain, and at the internal boundary of the nucleus.

Our model, therefore, captures all of the essential physics of microtubule dynamics including mechanics, polymerization kinetics, and the diffusion of tubulin and tau concentrations. We will now present some results from our model applied to a simplified geometry.

Results

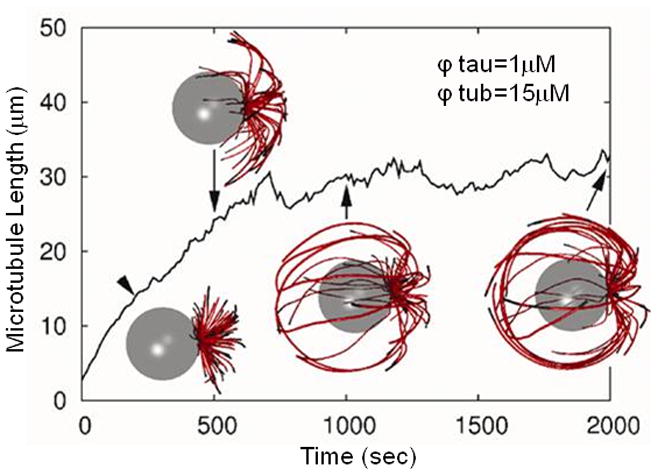

The evolution of a system with ϕtau = 1 μM and ϕtub = 15 μM is shown in Figure 1. The average length of microtubules in the system is shown as a function of time. The average length is initially set to a small number but increases with time until a steady state dynamic instability is reached. To emphasize the evolution of this system, snapshots at various times during these early stages of the simulation are shown. The density of microtubules increases as a function of time. In particular, the microtubules are initiated at a single microtubule organizing center and increasingly extend to the cell membrane which defines the boundary of the cell.

Figure 1.

The average microtubule length in a system with ϕtau = 1 μM and ϕtub = 15 μM, as a function of time. Snapshots showing microtubule morphology are depicted at various times. The nucleus is represented by a transparent sphere and the microtubules are represented by red (GDP) and black (GTP) cylinders.

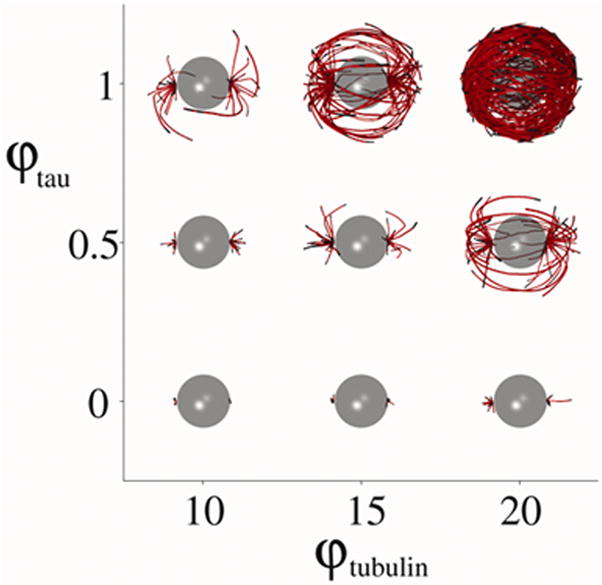

Figure 2 shows snapshots of systems with varying tubulin and tau concentrations which have evolved to steady state. Tubulin concentrations ranging from ϕtub = 10 μM to 20 μM and the tau concentration ranging from ϕtau = 0 μM to 1 μM were used in the model. As either of the concentrations increase the effects on the microtubule morphology is significant. Increasing the concentrations increases the rate of polymerization and results in much longer microtubules. In particular, for the parameters considered here, the system with ϕtub = 20 μM and ϕtau = 1 μM results in a dense network of microtubules around the interior of the cell. In patients with AD, tau fibrils in neurons, which are characteristic of disease (Castellani et al., 2006; Castellani et al., 2008), display a remarkably similar progression as predicted by our model (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

A) A series of snapshots of cells with a single microtubule organizing center, at steady state microtubule dynamics. The effects of varying tubulin and tau concentrations on the microtubule morphology are depicted. B) In AD, tau polymers form and accumulate progressively (A–D) within neuronal cell bodies similarly to the presented model. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Increasing the number of microtubule organizing centers from one to two results in qualitatively similar results to the model with one microtubule organizing center (Figure 3). In particular, the dramatic increase in microtubules as the concentrations of tubulin and tau are increased.

Figure 3.

A series of snapshots of cells with two microtubule organizing centers, at steady state microtubule dynamics. The effects of varying tubulin and tau concentrations on the microtubule morphology are depicted.

To quantify these effects, in Figure 4a, we plot the average number of microtubules per organizing center, and their average length, as a function of the rate of polymerization (with initial concentrations). Systems with either one or two microtubule organizing centers are shown. The data represents the average of the last 1000 of 5000 simulations. As can be seen, the number of chains increases with the increase in polymerization rate. Interestingly, the increase in average microtubule length shows a similar trend. Note that the nucleation rate of microtubules is unaffected by the concentrations (although this could easily be included in the model) and the increase in the number of chains is entirely a consequence of the increased rate of polymerization. In other words, longer and faster growing chains might be expected to have larger GTP-tubulin caps and, therefore, a reduced probability of undergoing catastrophic failure. The percentage of microtubules which contain GDP-tubulin, and the average cap size of the microtubules, are shown as a function of the rate of polymerization in Figure 4b. As the concentrations are increased, and the rate of polymerization increases, the amount of GDP-tubulin, relative to the total amount of tubulin in the microtubules increases. For systems with increased concentrations the microtubules are longer and the tubulin bound within the microtubules has a longer time to hydrolyze from GTP-tubulin to GDP-tubulin. Therefore, the fraction of GDP-tubulin is larger in systems with greater tubulin and tau concentrations. Conversely, systems with smaller concentrations of tubulin and tau undergo a relatively faster turn-around of the tubulin bound within the microtubules (as they have a greater chance of depolymerizing), and this results in less time for the tubulin to hydrolyze from GTP-tubulin to GDP-tubulin. Systems with a faster rate of polymerization are found to possess larger cap sizes. The polymerization of the microtubule GTP-tubulin cap, and the hydrolysis of this GTP-tubulin to GDP-tubulin, are both simulated in our model as stochastic events. Therefore, if (by chance) the GTP-tubulin hydrolyzes to GDP-tubulin, prior to the further polymerization of the microtubule, then the end of the microtubule will consist of GDP-tubulin, at which point the depolymerization of the chain becomes much more likely.

Figure 4.

a) The average number of microtubule per organizing center (○) and the average length of microtubules (Δ) as a function of polymerization rate. b) The average cap size (○) and the percentage of microtubule chains which are GDP (Δ) as a function of polymerization rate. The tubulin concentrations are varied from 10 μM to 20 μM and the tau concentration from 0 μM to 1 μM, and consider both systems with one and two microtubule organizing centers.

The cap sizes found here are small, but such differences in cap size would appear to be significant enough to alter the probability of depolymerization. This ultimately results in an increase in the average number and length of the microtubules, and the dramatic differences in microtubule morphology.

Conclusions

To summarize, we present a new computer model of microtubule dynamics which integrates the linear elasticity of microtubule mechanics, a stochastic model of microtubule polymerization kinetics and the diffusion of both tubulin and tau. This three-dimensional model is applied to a simplified geometry and microtubule dynamic instability observed, where the dynamics and morphology of the microtubules are significantly affected by the tubulin and tau concentrations. Tau, when bound to microtubules, can prevent the hydrolysis of GTP-tubulin to GDP-tubulin, affecting polymerization and depolymerization. Ultimately, the stochastic nature of hydrolysis results in heterogeneous microtubules which, in general, consist of GDP-tubulin and a small cap of GTP-tubulin, but there are often patches of GTP-tubulin further down the microtubule away from the cap. The catastrophic depolymerization of microtubules whose ends contain GDP-tubulin can be terminated if the end of the microtubule consisting of GDP-tubulin depolymerizes to reveal a section of the microtubule which contains GTP-tubulin. At this point, the catastrophic depolymerization of the microtubule is arrested. However, if this section of GTP-tubulin hydrolyzes to GDP-tubulin, before the microtubule can polymerize, then catastrophic depolymerization will continue. If, on the other hand, polymerization occurs first then the microtubule will be rescued through the establishment a new polymerizing cap containing GTP-tubulin. Future work will investigate these catastrophe and rescue events with respect to the current polymerization and hydrolysis rates (Brun et al., 2009; Hinow et al., 2009).

As a model for translational research, bridging basic science to bedside understanding and treatment for disease, future work will apply this model to specific disease systems with more complicated environments, for instance incorporating the various tau phosphorylation states, mutant tau forms and subsequent insolubility issues which are features of many neurodegenerative diseases (Panda et al., 2003). Even synuclein, the major protein implicated in Parkinson’s disease, can promote microtubule assembly, an activity that is lost with synuclein mutations (Yoshii and Ueda, 2004). Modeling new classes of microtubule-targeting agents for the treatment of cancers will also benefit from accurate computer simulations (Risinger et al., 2009). Of specific interest is taxol, a compound that stabilizes microtubules. Although its exact mechanism of action is unclear, the result is inhibition of microtubule dynamics, impaired cell function, and eventual cell death. Research suggests that taxol crystals resemble microtubules, which act to bind tubulin, affecting the microtubule dynamics and add a new dimension to potential action of this anti-tumor strategy (Foss et al., 2008). The utility of this model to dissect AD- and cancer-related abnormalities may open new options for therapeutic intervention. It is expected that through our computer simulations we can enhance our understanding of microtubule dynamics and, furthermore, by applying computer models to systems of microtubule dysfunction we can understand one of the most fundamental cellular structures altered in disease.

Research Highlights.

The presented three-dimensional mathematical model simulates microtubule dynamics within cells.

This model incorporates polymerization kinetics and hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, and allows the microtubules to move dynamically within a “cell” defined by a cellular membrane.

The regional concentrations of tubulin and tau are also included parameters that affect microtubule polymerization and depolymerization.

This model can be modified to mimic microtubule dynamics in sporadic disease systems as well as predict the effect of various treatment options that directly affect microtubules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG028679) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

Abbreviation List

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brun L, Rupp B, Ward JJ, Nedelec F. A theory of microtubule catastrophes and their regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21173–21178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910774106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton GA, Balazs AC. Modeling the dynamic fracture of polymer blends processed under shear. Phys Rev B. 2004;69:054101. [Google Scholar]

- Cash AD, Aliev G, Siedlak SL, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Zhu X, Raina AK, Vinters HV, Tabaton M, Johnson AB, Paula-Barbosa M, Avila J, Jones PK, Castellani RJ, Smith MA, Perry G. Microtubule reduction in Alzheimer’s disease and aging is independent of tau filament formation. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1623–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64296-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Lee HG, Zhu X, Nunomura A, Perry G, Smith MA. Neuropathology of Alzheimer disease: pathognomonic but not pathogenic. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2006;111:503–509. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Lee HG, Zhu X, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer disease pathology as a host response. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:523–531. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318177eaf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YD, Hill TL. Theoretical studies on oscillations in microtubule polymerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:8419–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey WT, Kalmykov YP, Waldron JT. The Langevin equation: with applications in physics, chemistry, and electrical engineering. World Scientific Publishing Company; Singapore: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino Lagomarsino M, Tanase C, Vos JW, Emons AM, Mulder BM, Dogterom M. Microtubule organization in three-dimensional confined geometries: evaluating the role of elasticity through a combined in vitro and modeling approach. Biophys J. 2007;92:1046–1057. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deymier PA, Yang Y, Hoying J. Effect of tubulin diffusion on polymerization of microtubules. Physical review. 2005;72:021906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.021906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, Kirschner MW. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1141–1154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson HP, O’Brien ET. Microtubule dynamic instability and GTP hydrolysis. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg H, Holy TE, Leibler S. Stochastic dynamics of microtubules: A model for caps and catastrophes. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;73:2372–2375. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss M, Wilcox BW, Alsop GB, Zhang D. Taxol crystals can masquerade as stabilized microtubules. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. Tau is actin up in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature cell biology. 2007;9:133–134. doi: 10.1038/ncb0207-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TL. Introductory analysis of the GTP-cap phase-change kinetics at the end of a microtubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:6728–6732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.21.6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinow P, Rezania V, Tuszynski JA. Continuous model for microtubule dynamics with catastrophe, rescue, and nucleation processes. Physical review. 2009;80:031904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.031904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holy TE, Leibler S. Dynamic instability of microtubules as an efficient way to search in space. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5682–5685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nature reviews. 2004;4:253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konzack S, Thies E, Marx A, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Swimming against the tide: mobility of the microtubule-associated protein tau in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9916–9927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0927-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristofferson D, Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Direct observation of steady-state microtubule dynamics. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1007–1019. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.3.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb B. Hydrodynamics. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Landau LD, Lifschitz EM. Theory of Elasticity. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Chohan MO, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Disruption of microtubule network by Alzheimer abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:501–511. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0207-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrides V, Shen TE, Bhatia R, Smith BL, Thimm J, Lal R, Feinstein SC. Microtubule-dependent oligomerization of tau. Implications for physiological tau function and tauopathies. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33298–33304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx J. Alzheimer’s disease. A new take on tau Science. 2007;316:1416–1417. doi: 10.1126/science.316.5830.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra PK, Kunwar A, Mukherji S, Chowdhury D. Dynamic instability of microtubules: effect of catastrophe-suppressing drugs. Physical review. 2005;72:051914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.051914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature. 1984;312:237–242. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda D, Samuel JC, Massie M, Feinstein SC, Wilson L. Differential regulation of microtubule dynamics by three- and four-repeat tau: implications for the onset of neurodegenerative disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9548–9553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633508100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez M, Santa-Maria I, Gomez de Barreda E, Zhu X, Cuadros R, Cabrero JR, Sanchez-Madrid F, Dawson HN, Vitek MP, Perry G, Smith MA, Avila J. Tau--an inhibitor of deacetylase HDAC6 function. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1756–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehl M, Tulu US, Wadsworth P, Cassimeris L. Centrosome maturation: measurement of microtubule nucleation throughout the cell cycle by using GFP-tagged EB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1584–1588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308205100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania V, Tuszynski J. A first principle (3+1) dimensional model for microtubule polymerization. Phys Lett A. 2008;372:7051–7056. [Google Scholar]

- Risinger AL, Giles FJ, Mooberry SL. Microtubule dynamics as a target in oncology. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sept D, Limbach HJ, Bolterauer H, Tuszynski JA. A chemical kinetics model for microtubule oscillations. J Theor Biol. 1999;197:77–88. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpil’man AA, Nadezhdina ES. Stochastic computer model of cellular microtubule dynamics. Biofizika. 2006;51:880–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Richey Harris PL, Sayre LM, Beckman JS, Perry G. Widespread peroxynitrite-mediated damage in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2653–2657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Richey PL, Taneda S, Kutty RK, Sayre LM, Monnier VM, Perry G. Advanced Maillard reaction end products, free radicals, and protein oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;738:447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski JQ, Smith AB, Huryn D, Lee VM. Microtubule-stabilising drugs for therapy of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders with axonal transport impairments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:683–686. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBuren V, Cassimeris L, Odde DJ. Mechanochemical model of microtubule structure and self-assembly kinetics. Biophys J. 2005;89:2911–2926. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorobjev IA, Maly IV. Microtubule length and dynamics: Boundary effect and properties of extended radial array. Cell and Tissue Biol. 2008;2:272–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorobjev IA, Rodionov VI, Maly IV, Borisy GG. Contribution of plus and minus end pathways to microtubule turnover. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 ( Pt 14):2277–2289. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.14.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii M, Ueda K. Microtubule dynamics can be central in Parkinson’s disease as well as in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2004;4:17–19. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.