Abstract

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory disease process resulting from the interaction of a bacterial attack and host inflammatory response. Arrays of molecules are considered to mediate the inflammatory response at one time or another, among these are free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Periodontal pathogens can induce ROS overproduction and thus may cause collagen and periodontal cell breakdown. When ROS are scavenged by antioxidants, there can be a reduction of collagen degradation. Ubiquinol (reduced form coenzyme Q10) serves as an endogenous antioxidant which increases the concentration of CoQ10 in the diseased gingiva and effectively suppresses advanced periodontal inflammation.

Keywords: Antioxidant, bioenergizer, coenzyme Q10, periodontal disease

Coenzyme Q10 (also known as ubiquinone) was discovered by Crane and his colleagues in 1957 in beef heart mitochondria.[1] It was first isolated from the mitochondria of bovine hearts in 1957 at the University of Wisconsin. Identification of the chemical structure and synthesis was completed by 1958. Because of its ubiquitous presence in nature and its quinone structure (similar to that of vitamin K), coenzyme Q10 is also known as ubiquinone.[2]

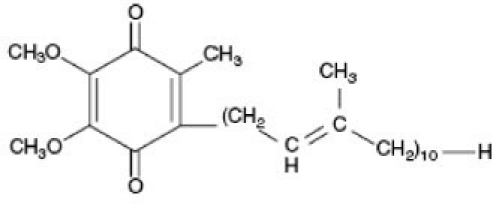

Coenzyme Q10 is a naturally occurring coenzyme formed from the conjugation of a benzoquinone ring with a hydrophobic isoprenoid chain of varying chain length, depending on the species.[3] The chemical nomenclature of CoQ10 is 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-decaprenyl-1,4-benzoquinone that is in the trans configuration (natural).[4]

Structure of coenzyme Q10.

It is found in every plant and animal cell, and is located in the inner membrane system of the mitochondria, other membranes, and in plasma lipoproteins. The well-recognized function of coenzyme Q10 is mitochondrial energy coupling. It is an essential part of the cellular machinery used to produce ATP which provides the energy for muscle contraction and other vital cellular functions. The major part of ATP production occurs in the inner membrane of mitochondria, where coenzyme Q is found. The other important function is that it acts as a primary scavenger of free radicals (FRs) as it is well located in the membranes in close proximity to the unsaturated lipid chains. Less well-established functions include oxidation/reduction control of signal origin and transmission in cells which induce genre expression, control of membrane channels, structure, and lipid solubility.[5]

Bacteria possess several structurally different quinones, among which ubiquinone (UQ), menaquinone (MK) and demethylmenaquinone (DMK) are the most common. These quinones are found in the cytoplasmic membrane, where they participate as electron carriers in respiration and in the disulfide-bond formation. UQ participates in aerobic respiration, whereas MK and DMK have roles in anaerobic respiration. UQ molecules are classified based on the length (n) of their isoprenoid side chain (UQ-n). For example, the main UQ species in humans is UQ-10, in rodents it is UQ-9, in Escherichia coli it is UQ-8 and, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it is UQ-6 in varying amounts.[3] Coenzyme Q9 is the predominant form in relatively short-lived species such as rats and mice whereas in humans and other long-lived mammals the major homolog is coenzyme Q10. Among blood cells, lymphocytes and platelets contain significant amounts of CoQ10 whereas red blood cells which lack mitochondria contain only a tiny amount that is likely to be associated with membranes. Lymphocyte CoQ10 content can be increased by CoQ10 supplementation with concomitant functional improvement as evidenced by enhanced reversal of oxidative DNA damage.[6] The total body pool of CoQ10 is estimated to be approximately 0.5–1.5 g in a normal adult.[4] Human cells synthesize CoQ10 from the amino acid tyrosine, in an eight-step aromatic pathway, requiring adequate levels of vitamins such as folic acid, niacin, riboflavin, and pyridoxine.[7]

The functions, indications and contraindications of coenzyme Q10 are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of currently recognized functions, indications and contraindications of coenzyme Q10

| Functions[1] | Indications[2] | Contraindications[4] |

|---|---|---|

|

Immune function Periodontal disease | No data have evaluated the safety or toxicity of CoQ10 during pregnancy, lactation or childhood. Therefore, its use is not recommended in these patient populations. |

| Gastric ulcers | ||

| Obesity | ||

|

Physical performance | |

| Muscular dystrophy | All natural products carry the potential for allergic reactions, however, to date, none have been reported with the use of CoQ10.[4] | |

|

Allergy | |

| Cardiovascular disease: Specific cardiac problems which may benefit include: Cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, angina, arrhythmias, prevention of adriamycin toxicity, protection during cardiac surgery, mitral valve prolapse, hypertension, male infertility, diabetes mellitus. | ||

|

||

|

Coenzyme Q10 Deficiency

Since CoQ10 is synthesized de novo in all tissues, it is presumed that under normal circumstances they are not dependent on an exogenous supply of CoQ10. Although CoQ10 can be synthesized “in vivo,” situations may arise in which the body’s synthetic capacity is insufficient to meet CoQ10 requirements. Susceptibility to CoQ10 deficiency appears to be greatest in cells that are metabolically active (such as those in the heart, immune system, gingiva, and gastric mucosa), since these cells presumably have the highest requirements for CoQ10.[2]

A deficiency may result from:[2]

Impaired synthesis due to nutritional deficiencies

Genetic or acquired defect in synthesis or utilization

Increased tissue needs resulting from illness

CoQ10 levels decline with advancing age

Assessment of CoQ10 status

Plasma or serum CoQ10 concentrations are usually employed for the assessment of CoQ10 status in humans primarily because of the ease of sample collection. There are several excellent methods based on high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) for the analysis of CoQ10 in plasma or serum and fasting samples are preferred. Plasma CoQ10 concentrations may not necessarily reflect tissue status; it still serves as a useful measure of overall CoQ10 status and also as a guide to CoQ10 dosing. This is particularly true of degenerative neurologic and muscular diseases where clinical monitoring of plasma CoQ10 concentration and also its redox status are highly desirable that could provide valuable information as to the course of treatment. Lymphocyte and platelet CoQ10 concentrations could also be considered as potential surrogates for tissue CoQ10 status.[6]

Pharmacokinetics

CoQ10 is now recommended as a supplement to traditional therapy for cardiovascular diseases.[8] Though CoQ10 is a lipophilic compound, its solubility is extremely limited and the preparations are often characterized by low bioavailability.[9] Absorption of the substance largely depends on its physiochemical characters in the preparation and hence coenzyme Q10 in powder, suspension, oil solution, or solubilized form exhibits different bioavailability. Study has shown that solubilized coenzyme Q10 is obviously preferred due to its better absorption, higher plasma concentration, and consequently better bioavailability[10] indicating that plasma concentrations of coenzyme Q10 are 2–2.5 times higher during long-term oral therapy with solubilized forms[11] and the bioavailability is 3–6 times higher in comparison with powder.[12,13] The pharmacokinetic advantages of solubilized form are responsible for its high efficiency as a cardioprotector: chronic oral treatment led to an increase of not only plasma levels of coenzyme Q10 (2.5 times), but of also its concentration in rat myocardium, which improved survival of cardiomyocytes under conditions of ischemia and eventually limited the size of the postinfarction necrotic zone.[10]

Dosage

The optimal dose of coenzyme Q10 is not known, but it may vary with the severity of the condition being treated.[2] Coenzyme Q10 is available as a dietary supplement in strengths generally ranging from 15 to 100 mg. In cardiovascular disease patients, CoQ10 dosages generally range from 100 to 200 mg per day. Dosages of up to 15 mg/kg/day are being employed in the case of mitochondrial cytopathy patients. A dosage of 600 mg per day was used in the Huntington’s disease trial whereas a dosage of up to 1200 mg per day was employed in the Parkinson’s disease trial.[4]

Safety of CoQ10

CoQ10 has an excellent safety record. The safety of high doses of orally ingested CoQ10 over long periods is well documented in human subjects and also by chronic toxicity studies in animals. The side effects reported in human studies are generally limited to mild gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and stomach upset seen in a small number of subjects. No adverse effects were observed with daily doses ranging from 600 to 1200 mg in two trials on Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases. More recent data document the safety and tolerability of CoQ10 at doses as high as 3000 mg per day in patients with Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[4]

CoQ10 and periodontitis

Chronic periodontitis is the direct result of accumulation of subgingival plaque. The microflora of this plaque is extremely complex causing problems in establishing which organisms are responsible for tissue destruction associated with the disease. Despite these problems, there is one point on which investigators agree, the subgingival flora of healthy gingival crevice is sparse and consists largely of aerobic and facultative bacteria, while in diseased state there is an increase in the proportion of anaerobic bacteria. These bacteria cause the observed tissue destruction directly by toxic products and indirectly by activating host defense systems, i.e. inflammation.[14] Inflammation represents the response of the organism to a noxious stimulus, whether mechanical, chemical, or infectious. It is a localized protective response elicited by injury or destruction of tissues, which serves to destroy, dilute, or wall off both the injurious agent and the injured tissue. Whether acute or chronic, inflammation is dependent upon regulated humoral and cellular responses, and the molecules considered to mediate inflammation at one time or another are legion.[1] However, an event characteristic of mammalian inflammation, tissue infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes and subsequent phagocytosis features non-mitochondrial O2 consumption, which may be 10 or 20 times that of resting consumption ultimately ends in generating free radicals (FRs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anion radicals, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, and hypochlorous acid, all capable of damaging either cell membranes or associated biomolecules.[14] Because of their high reactivity, several FRs and ROS can rapidly modify either small, free biomolecules (i.e., vitamins, amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids) or macromolecules (i.e., proteins, nucleic acids) or even supramolecular structure (i.e., cell membranes, circulating lipoproteins). The type and the extent of damage depend upon the site of generation. Usually, the oxidative damage is perfectly controlled by the anti-oxidant defense mechanisms of the surrounding tissues but plaque microorganisms promoting periodontitis can unbalance this equilibrium. A massive neutrophil migration to the gingiva and gingival fluid leads to abnormal spreading of FR/ROS produced. Consequently, this led to a search for appropriate “antioxidant therapy” in inflammatory periodontal disease.[14]

A deficiency of coenzyme Q10 at its enzyme sites in gingival tissue may exist independently of and/or because of periodontal disease. If a deficiency of coenzyme Q10 existed in gingival tissue for nutritional causes and independently of periodontal disease, then the advent of periodontal disease could enhance the gingival deficiency of coenzyme Q10.[15] In such patients, oral dental treatment and oral hygiene could correct the plaque and calculus, but not that part of the deficiency of CoQ10 due to systemic cause; therapy with CoQ10 can be included with the oral hygiene for an improved treatment of this type of periodontal disease.[15]

The specific activity of succinic dehydrogenase–coenzyme Q10 reductase in gingival tissues from patients with periodontal disease against normal periodontal tissues has been evaluated using biopsies, which showed a deficiency of CoQ10 in patients with periodontal disease. On exogenous CoQ10 administration, an increase in the specific activity of this mitochondrial enzyme was found in deficient patients.[15–18] The periodontal score was also decreased concluding that CoQ10 should be considered as an adjunct for the treatment of periodontitis in current dental practice.[19]

Not only succinate dehydrogenase CoQ10 reductase, but also succinate cytochrome c reductase and NADH cytochrome c reductase showed decreased specific activity in periodontitis patients.[20] On exogenous administration of CoQ10 showed improved specific activity of these enzymes with significant reduction of motile rods and spirochetes.[21] The preliminary data indicated that CoQ10 may reduce gingival inflammation without affecting GCF total antioxidant levels,[22] whereas one more study showed significant reduction in TBRAS in GCF in patients treated with scaling and root planning with CoQ10.[23]

Topical application of CoQ10 to the periodontal pocket was evaluated with and without subgingival mechanical debridement. In the first three-week period, significant reduction in gingival crevicular fluid flow, probing depth and attachment loss were found and significant improvements in modified gingival index, bleeding on probing and peptidase activity derived from periodontopathic bacteria were observed only at experimental sites (CoQ10 with subgingival mechanical debridement).[24] It suggested that the research literature on coenzyme Q10 ’s periodontal effect does not extend to International English language dental literature. The review of available literature does not give any ground for the claims regarding benefit of coenzyme Q10 and has no place in periodontal treatment.[25]

A study evaluated the periodontium condition after oral applications of coenzyme Q10 with vitamin E. The total antioxidant status (TAS) in the mixed saliva by the colorimetric method was determined twice. The average value of plaque index decreased from 1.0 to 0.36, average value of interdental hygiene index was reduced from 39.51–6.97%, gingival index values decreased from 0.68 to 0.18, and the values of sulcus bleeding index decreased from 7.26 to 0.87. Periodontal pockets also shallowed by 30%. The laboratory examination result improved by 20%. It concluded that coenzyme Q10 with vitamin E had a beneficial effect on the periodontal tissue.[26]

Because it is an antioxidant, coenzyme Q10 has received much research attention in the medical literature in the last several years. Although coenzyme Q10 may have been viewed as an alternative medication, it is used routinely, both topically and systemically, by many believing dentists and periodontists. However, there is a dearth of new information for coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of periodontal conditions. A deficiency of CoQ10 has been found in the gingiva of patients with periodontal disease.[15,16] Gingival biopsies from patients with inflamed periodontal tissues showed a deficiency of CoQ10, in contrast to patients with normal periodontal tissues. Many clinical trials with oral administration of CoQ10 to patients with periodontal disease have been conducted. The results have shown that oral administration of CoQ10 increases the concentration of CoQ10 in the diseased gingiva and effectively suppresses advanced periodontal inflammation[17,27,28] and periodontal microorganisms. Clinical study with interpocket application has shown CoQ10 is an effective adjunctive in the treatment of chronic periodontitis and also found to enhance the resistance of the periodontal tissues to periodontopathic bacteria (unpublished data).

Conclusion

The concept of ROS-induced destruction has led to search for an appropriate complimentary antioxidant therapy in the treatment of numerous diseases including inflammatory periodontal diseases. Because it is an antioxidant, there is a dearth of new information for coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of periodontal conditions. The pharmacology of coenzyme Q10 indicates that it may be an agent for treatment of periodontitis. On the basis of on new concepts of synergism with nutritional supplements and host response, coenzyme Q10 may possibly be effective as a topical and/or systemic role or adjunctive treatment for periodontitis either as a stand-alone biological or in combination with other synergistic antioxidants (i.e., vitamins C and E).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bliznakov EG, Chopra RK, Bhagavan HN. Coenzyme Q10 and neoplasia: Overview of experimental and clinical evidence. In: Bagchi D, Preuss HG, editors. Phytopharmaceuticals in Cancer Chemoprevention. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2004. pp. 599–622. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaby AR. The role of Coenzyme Q10 in clinical medicine: Part I. Alt Med Rev. 1996;1:11–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cluis CP, Burja AM, Martin VJ. Current prospects for the production of coenzyme Q10 in microbes. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhagavan HN, Chopra RK. Coenzyme Q10: Absorption, tissue uptake, metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:445–53. doi: 10.1080/10715760600617843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crane FL. Biochemical functions of Coenzyme Q10. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:591–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomasetti M, Alleva R, Borghi B, Collins AR. Collins In vivo supplementation with coenzyme Q10 enhances the recovery of human lymphocytes from oxidative DNA damage. FASEB J. 2001;15:1425–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0694fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dallner G, Brismar K, Chojnacki T, Swiezewska E. Regulation of coenzyme Q biosynthesis and breakdown. Biofactors. 2003;18:11–22. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weant KA, Smith KM. The role of coenzyme Q10 in heart failure. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1522–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ullmann U, Metzner J, Schulz C, Perkins J, Leuenberger B. A new Coenzyme Q10 tablet-grade formulation (all-Q) is bioequivalent to Q-Gel and both have better bioavailability properties than Q- -SorB. J Med Food. 2005;8:397–9. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalenikova EI, Gorodetskaya EA, Kolokolchikova EG, Shashurin DA, Medvedev OS. Chronic administration of coenzyme Q10 limits postinfarct myocardial remodeling in rats. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2007;72:407–15. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907030121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra RK, Goldman R, Sinatra ST, Bhagavan HN. Relative bioavailability of coenzyme Q10 formulations in human subjects. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1998;68:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miles M, Horn P, Miles L, Tang P, Steele P, DeGraw T. Bioequivalence of coenzyme Q10 from over-the-counter supplements. Nutr Res. 2002;22:919–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaghloul AA, Gurley B, Khan M, Bhagavan H, Chopra R, Reddy I. Bioavailability assessment of oral coenzyme Q10 formulations in dogs. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2002;28:1195–200. doi: 10.1081/ddc-120015352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battino M, Bullon P, Wilson M, Newman H. Newman Oxidative injury and inflammatory periodontal diseases: The challenge of anti-oxidants to free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:458–76. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura R, Littarru GP, Folkers K, Wilkinson EG. Deficiency of coenzyme Q in gingival tissue from patients with periodontal disease. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1973;43:84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littarru GP, Nakamura R, Ho L, Folkers K, Kuzell WC. Deficiency of coenzyme Q10 in gingival tissue from patients with periodontal disease. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2332–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.10.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson EG. Bioenergetics in clinical medicine. II. Adjunctive treatment with coenzyme Q in periodontal treatment. Res Commun Chemic Path Pharm. 1975;12:111–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura R, Littarru GP, Folkers K, Wilkinson EG. Study of CoQ10-enzymes in gingiva from patients with periodontal disease and evidence for a deficiency of coenzyme Q10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:1456–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkinson EG, Arnold RM, Folkers K. Bioenergetics in clinical medicine. VI. Adjunctive treatment of periodontal disease with CoQ10. Res Commun Chem Path Pharmac. 1976;14:715–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shizukuishi S, Inoshita E, Tsunemitsu A, Takahashi K, Kishi T, Folkers K. Therapy by Coenzyme Q10 of experimental periodontitis in a dog-model supports results of human periodontitis therapy. In: Folkers K, Yamamura Y, editors. Biomedical and clinical aspects of Coenzyme Q. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1984. pp. 153–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McRee JT, Hanioka T, Shizukuishi S, Folkers K. Therapy with Coenzyme Q10 for patients with periodontal disease. 1. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 on subgingival micro-organisms. J Dent Health. 1993;43:659–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denny N, Chapple IL, Matthews JB. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of coenzyme Q10: A preliminary study. J Dent Res. 1999;78:543. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuru B, Yildiz D, Kayalı R, Akçay T. Gingival lipid peroxidation and glutathione redox cycle before and after periodontal treatment with and without adjunctive Coenzyme Q10. Turkiye Klinikleri J Dental Sci. 2006;12:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanioka T, Tanaka M, Ojima M, Shizukuishi S, Folkers K. Effect of topical application of coenzyme Q10 on adult periodontitis. Mole Aspects Med. 1994;15:s241–8. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watts TL. Coenzyme Q10 and periodontal treatment: Is there any beneficial effect? Br Dent J. 1995;178:209–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brzozowska TM, Flisykowska AK, OEwitkowska MW, Stopa J. Healing of periodontal tissue assisted by Coenzyme Q10 with Vitamin E: Clinical and laboratory evaluation. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:257–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shizukuishi S, Hanioka T, Tsunemitsu A, Fukunaga Y, Kishi T, Sato N. Clinical effect of Coenzyme 10 on periodontal disease; evaluation of oxygen utilisation in gingiva by tissue reflectance spectrophotometry. In: Shizukuishi S, Hanioka T, Tsunemitsu A, editors. Biomedical and clinical aspects of Coenzyme Q. Vol. 5. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1986. pp. 359–68. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McRee JT, Hanioka T, Shizukuishi S, Folkers K. Therapy with Coenzyme Q10 for patients with periodontal disease. 1. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 on subgingival micro-organisms. J Dent Health. 1993;43:659–66. [Google Scholar]