Abstract

Background

Psoriasis exerts significant, negative, impact on patients' quality of life (QOL). Recently, the relationship between QOL and skin lesion improvement has been emphasized in the treatment of psoriasis patients.

Objective

The purpose of study was to compare the QOL in psoriasis and other skin diseases, and to evaluate the generic QOL, skin specific QOL, stress, depression and anxiety before and after treatment in patients.

Methods

A total of 138 patients with psoriasis were recruited in this study and 83 patients complete the questionnaire at week 16. Questionnaires were comprised of generic WHO QOL scale, dermatology specific questionnaires (Skindex-29), psoriasis life stress inventory (PLSI), Beck depression inventory (BDI), and Beck anxiety inventory (BAI). Clinical response was assessed by the PASI.

Results

After treatment, health-related QOL was improved and PASI improvement showed smaller correlation with Skindex-29, compared with the correlations between self-reported severity score (SRSS) improvement and Skindex-29. Regression analysis revealed that duration, SRSS, stress, and depression were factors affecting baseline HRQOL in patients, and age, duration, and SRSS were predictors associated with HTQOL score changes.

Conclusion

Treatment improved HRQOL, BAI, BDI, and PLSI scores. Psoriasis may become more burdensome in groups of patients who suffer long disease duration, high SRSS, depression, and stressful environments.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Ever since the English economist Arthur Cecil Pigou introduced quality of life (QOL) in economics, the expression "QOL" has been defined in many ways and has been used differently by various investigators owing to its elusive nature1. QOL is multi-dimensional and determined by health and multiple non-medical aspects, such as socioeconomic status, marital status, personality, happiness, ambition, and religious experience2. Health-related QOL (HRQOL) has been defined as peoples' subjective evaluation of the influences of their current health status on their ability to achieve and maintain a level of overall functioning that allow them to pursue valued life goals and that are reflected in their general well being3. According to the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, attention is increasingly directed to the patient's QOL and, in the last several decades, various functional indexes were developed and QOL was frequently measured in the medical literature. It has been studied in many chronic diseases such as diabetes4, hypertension5, atrial fibrillation6, gastric cancer7, and congestive heart failure8. In chronic non-life-threatening diseases, such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo, HRQOL has become increasingly important in the evaluation of disease severity, interventions, and allocation of resources2.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory, immune-mediated genetic disease with typical thickened, red, scaly plaques. The disease course is chronic, and treatment of psoriasis is aimed at inducing and maintaining remission. The comparison of psoriasis with other chronic, debilitating medical and psychiatric conditions suggests that, although not threatening to life itself, psoriasis can reduce physical and mental functioning comparable to that seen in cancer, arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and depression and can severely threaten QOL9. Another study also found that psoriasis was more detrimental to QOL than angina and hypertension10.

There has been much cross-sectional research on HRQOL impairment owing to psoriasis, but there has been little research concerning the impact of psoriasis comparing pre- and post-intervention QOL. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate QOL in psoriasis patients before and after treatment. Our second aim was to investigate the relationship between psoriasis area and severity inventory (PASI) improvement and QOL, depression, anxiety, and stress. We also elected to study the role of demographic factors, such as age, sex, marital status and educational level as possible mediator of impact on QOL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study patients

A total of 138 patients (80 male, 58%; 58 female, 42%) with psoriasis who visited the Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital between October 2007 and December 2009 were enrolled. The diagnoses were based on skin biopsies and clinical manifestations. Each patient completed the generic QOL instrument (WHOQOL-BREF), psoriasis specific QOL measure (Skindex-29), Beck anxiety inventory (BAI), Beck depression inventory (BDI), and psoriasis life stress inventory (PLSI) at the beginning of the study, and 83 patients completed the questionnaires at the end of the study. Uncooperative patients who did not participate in the study in its entirety were excluded. The comparator group consisted of 48 patients suffering from dermatological disease other than psoriasis, such as acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, fungal infection, and verruca vulgaris. And the control group was consisted of 30 healthy individuals. The groups were matched in terms of age, sex, and education levels.

Questionnaires

All subjects received a questionnaire package that included the followings:

1) The WHOQOL-BREF

To assess generic QOL, we used a generic instrument, the WHOQOL-BREF, to enable a brief but accurate assessment of the QOL11. This instrument was developed simultaneously by 15 academic centers worldwide under the auspices of the WHO. It consists of 24 items divided into four broad areas: physical health domain, psychological health domain, social relations domain, and environmental domain. In our study, the Korean version of the WHOQOL-BREF confirmed validity and reliability in the assessment of QOL12. The questionnaire uses 5-point scales for all questions with greater scores indicating better physical function and well-being.

2) Skindex-29

Skindex-29 was designed to measure dermatology-specific HRQOL in different population and to detect changes in time13. This instrument consists of 29 items, loading on emotional, functioning, and symptom domains. The questions refer to the previous 4-week period, and scores are given on a 5-point scale, from "never" to "all the time." Greater scores indicate poorer QOL. The scale scores were transformed into a linear scale, varying from 0 to 100. In the Korean version of Skindex-29, validity and reliability was demonstrated14.

3) The psoriasis life stress inventory

The PLSI measures the degree of subjective stress related to psoriasis experienced by the respondent within the last month15. The PLSI consists of a 15-item questionnaire that provides a measure of the daily psychosocial stress associated with having to cope with the daily events of psoriasis. The PLSI-B score reflects the degree of stress experienced on a 4-point scale, with scores from 0 to 3 corresponding to the following: 0=not at all, 1=mild degree, 2=moderate degree, and 3=a great deal. A total score of 10 and higher indicates more significant stress and more cosmetically disfiguring psoriasis.

4) Beck anxiety inventory

The BAI, a 21-item self-reported questionnaire, was used to evaluate the severity of anxiety. Individuals are asked to rate themselves on a spectrum of 0 to 3, corresponding to 0=least and 3=most. The total sum of scores shows the level and the severity of depression. In the Korean version of BAI, validity and reliability was demonstrated and a total score of more than 22 means patients have a significant anxiety disorder16.

5) Beck depression inventory

The BDI is a self-rating scale that evaluates 21 items of depression. Each question has four items rated from 0 to 3 points. The total sum shows the level and the severity of depression. Although 17 points and higher shows depression in general17, 13 points and higher shows depression in the Korean version of BDI18.

6) Psoriasis severity

The subjects were asked to rate their subjective experience on their psoriasis' severity on 11-point scales, with end-points representing 0=not at all and 10=to a very high degree. Severity of psoriasis was assessed by PASI. The subjects were assessed by a dermatologist using the PASI scoring system, and the area involved and the severity of erythema, infiltration, and desquamation were graded, resulting in ranges of total scores from 0 to 72. Four main areas were assessed to calculate the PASI scores: the head, trunk, upper extremities, and lower extremities, corresponding to 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% of the total body area, respectively. PASI is the most widely used measure of severity in research and in the clinical setting. This makes it an important tool in gauging the impact of the disease on QOL, although other instruments to measure QOL are also encouraged19. In the present study, PASI was assessed at baseline and at week 16.

Statistical analysis

We tested for the differences between psoriasis patients and other patients with other skin diseases, and those with no disease using analysis of variance (ANOVA), the Kruskall-Wallis test, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The proportions and ordinal data were analyzed with κ2 tests and other non-parametric tests. We used logistic regression to examine the association of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics with HRQOL score at baseline and change after treatment. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with the SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), version 17 for Windows.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

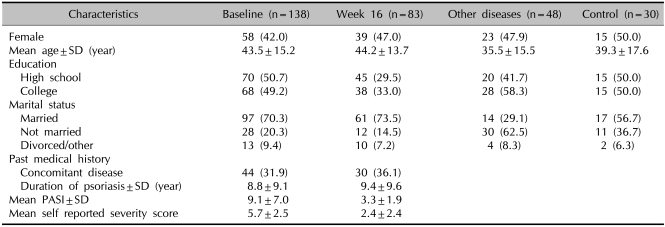

Differences in demographics and clinical disease characteristics between psoriasis patients and other control groups are presented in Table 1. The age of the psoriasis patients ranged between 19 and 85; the mean age was 43.5±15.2. Of the psoriasis cohort, 70.3% were married or living with a partner. Of the remaining subjects, 4.3% were divorced and 3.6% were widowed. There was no significant difference between patient groups. The mean duration of psoriasis among the participants was 8.8 years (±9.1 SD), with almost one third (31.9%) of participants having one or more other diseases. The mean PASI score at baseline was 9.1 (±7.0 SD), and 53.0% of participants had achieved a PASI of 75 or greater after treatment. The mean self-reported severity score (SRSS) was 5.7 (±2.5 SD).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants who had psoriasis, other skin disease, and healthy control group

SD: standard deviation, PASI: psoriasis area and severity index.

Impact of psoriasis on HRQOL

1) Comparison between the psoriasis group and other skin disease group

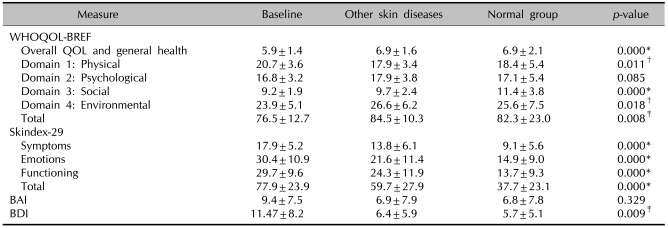

To compare psoriasis with other skin diseases in terms of impact on HRQOL, the mean scores of psoriasis patients were compared with that of healthy adults, and with individuals suffering other skin conditions such as acne vulgaris (62.5%), atopic dermatitis (14.6%), fungal infection (8.3%), and verruca vulgaris (6.3%). Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for these comparisons. The means for patients with psoriasis for general health, environmental domain, and total score were among the lowest among the cohorts. The means for patients with psoriasis for all domains of Skindex-29 and BDI were the lowest. Comparison with these other chronic conditions demonstrates that psoriasis imparts a more negative influence on HRQOL than other skin diseases.

Table 2.

Comparison between patients with psoriasis, patients with other skin diseases, and healthy adults

WHOQOL-BREF: WHO quality of life scale, QOL: quality of life, BAI: Beck anxiety inventory, BDI: Beck depression inventory. The Kruskal-Wallis test (WHOQOL-BREF score, Skindex-29 score, BAI score, BDI sore) compares subjects who had psoriasis with patients of other skin diseases, and a healthy control group. *p<0.001, †p<0.05, ‡p<0.01.

2) Mean changes from baseline to week 16 in PASI reduction and SRSS

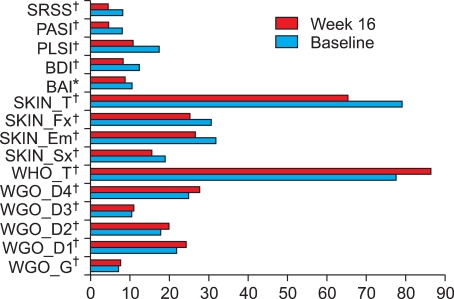

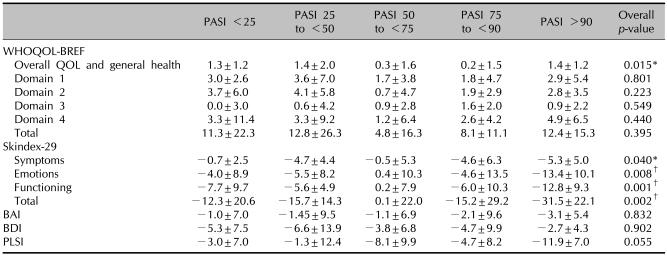

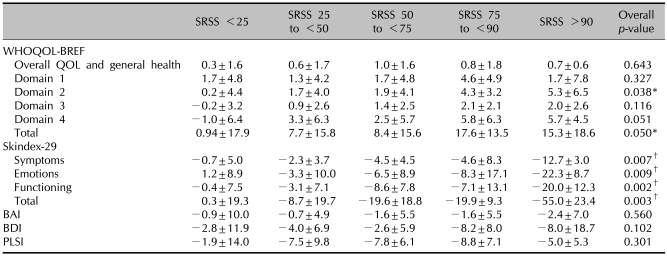

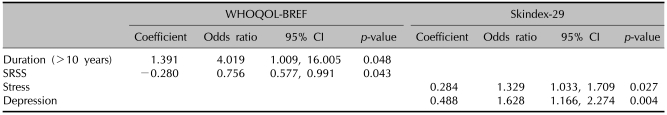

After treatment, mean PASI and SRSS scores were improved and the mean scores in HRQOL, BDI, and BAI were also improved. The mean changes from baseline to 16 weeks in WHOQOL total scores, Skindex-29 total scores, PLSI, BAI, and BDI were 8.7, -13.7, -6.6, -1.9, and -4.3, respectively (Fig. 1). All domains showed significant improvement statistically. The mean changes in WHOQOL-BREF, Skindex-29, BAI, BDI, and PLSI by PASI response are presented in Table 3. Statistically significant differences were observed in the general health domain of WHOQOL-BREF and Skindex-29. Patients achieving a PASI 75 or greater demonstrated greater improvement than the other PASI responder groups for all Skindex-29 domain scores. Mean changes in psychological domain and total score of WHOQOL-BREF, and all domains of Skindex-29 by SRSS improvement were statistically significantly different (Table 4). The difference in the mean change in BAI, BDI, and PLSI by PASI response and SRSS improvement were not statistically significantly different (p>0.05). In patients achieving a PASI 75 or greater, WHOQOL-BREF scores improved by 8.1 and 11.4 points, respectively, and Skindex-29 scores improved by -15.2 and -31.5, respectively. In patients who achieved a SRSS 75 or greater, WHOQOL-BREF scores improved by 17.6 and 15.3 points, respectively, and the Skindex-29 scores improved by -19.9 and -55.0, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Mean change for the WHOQOL-BREF, Skindex-29, BAI, BDI, PLSI, PASI, and SRSS between baseline and week 16 (*p<0.01, †p<0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test). WHOQOL-BREF: WHO quality of life scale, BAI: Beck anxiety inventory, BDI: Beck depression inventory, PLSI: psoriasis life stress inventory, PASI: psoriasis area and severity index; SRSS: self-reported severity score.

Table 3.

Mean change±SD from baseline to week 16 in WHOQOL-BREF, Skindex-29, BAI, BDI, PLSI by PASI responses

SD: standard deviation, WHOQOL-BREF: WHO quality of life scale, BAI: Beck anxiety inventory, BDI: Beck depression inventory, PLSI: psoriasis life stress inventory, PASI: psoriasis area and severity index. The Kruskal-Wallis test (WHOQOL-BREF score, Skindex-29 score, BAI score, BDI sore) compares subjects who have psoriasis with patients with other skin diseases and a normal control group. *p<0.05, †p<0.01.

Table 4.

Mean change±SD from baseline to week 16 in WHOQOL-BREF, Skindex-29, BAI, BDI, PLSI by SRSS improvement

SD: standard deviation, WHOQOL-BREF: WHO quality of life scale, BAI: Beck anxiety inventory, BDI: Beck depression inventory, PLSI: psoriasis life stress inventory, SRSS: self-reported severity score. The Kruskal-Wallis test (WHOQOL-BREF score, Skindex-29 score, BAI score, BDI sore) compares subjects who have psoriasis with patients with other skin diseases and a normal control group. *p<0.05, †p<0.01.

Predictors of HRQOL scores

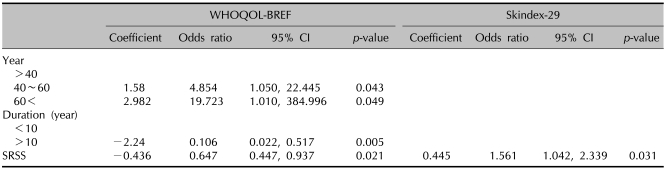

At baseline, the duration of psoriasis and SRSS was a significant factor associated with the total score of WHOQOL-BREF. Patients who suffered from psoriasis for more than 10 years made less impact on the baseline WHOQOL-BREF scores. Increased SRSS indicated greater impact of psoriasis on generic QOL. In Skindex-29, stress and depression were significant factors (Table 5). Logistic regression analysis associated HRQOL score change showed that age, duration of psoriasis, and SRSS were significant predictors. In the WHOQOL score, older patient were associated with greater improvement. Duration of more than 10 years and high SRSS scores affected generic QOL impairment. Only baseline SRSS was a significant predictor of change in Skindex-29 scores (Table 6). Interactions of sex, educational level, marital status, and co-morbidities were not significantly associated with any baseline HRQOL and change in HRQOL (data not shown).

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis of factors associated with baseline HRQOL score

HRQOL: health-related quality of life, WHOQOL-BREF: WHO quality of life scale, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval, SRSS: self-reported severity score.

Table 6.

Linear regression analysis of predictor associated HRQOL score change

HRQOL: health-related quality of life, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval, SRSS: self-reported severity score.

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis has a significant negative impact on patient's HRQOL. Psoriasis patients often experience difficulties, such as maladaptive coping responses, body image problems, shame and embarrassment regarding their appearance, and feelings of stigma20. Psoriasis patients had contemplated suicide21. Furthermore, the physical and emotional effects of psoriasis were found to have a significantly negative impact on patients' workplaces22. To our knowledge, although the effect of psoriasis on patients' lives has been studied extensively, few studies have assessed change in the impact of psoriasis. This study extended previous research on the impact of psoriasis on HRQOL, and compared HRQOL in patients with other skin diseases and focused on factors implicated in HRQOL changes.

In the current study, psoriasis have been shown to make significantly more impact on HRQOL, anxiety, depression and stress than in patients with other skin diseases, such as acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, fungal infection, and verruca vulgaris. Similarly, other studies showed that psoriasis patients were more likely to experience psychological distress, more so than in patients with other skin diseases such as urticaria, acne, alopecia, and eczema23,24. After treatment, the results of the current study demonstrate that improved psoriasis led to improved HRQOL, BAI, BDI, and PLSI. These finding imply that clinical improvement of psoriasis associates with anxiety, depression and stress, and physical improvement, and brought about change in psychological distress. Although another prospective study showed that clearance of psoriasis dose not impact upon psychological distress, patients were treated with photochemotherapy only25. In the present study, patients were treated with cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, ustekinumab, narrow-band ultraviolet B, and topical steroids.

As expected, Skinedx-29 scores and dermatology specific QOL correlated with PASI response and SRSS improvement. Skindex-29 scores correlated with SRSS improvement, with correlations raging from -0.268 to -0.320 (p<0.01, data not shown). PASI improvement showed smaller correlation with Skindex-29 (ranging from -0.162 to -0.226, p<0.05, data not shown), compared to that between SRSS improvement and Skindex-29. This finding revealed that the patients' own ratings of severity and symptoms were the best predictors of disease-related QOL. Although PASI scores used in clinical trials reflected psoriasis severity, it has been suggested that SRSS is also an important psoriasis severity assessment tool. These results suggest that physicians planning treatment for patients with psoriasis should consider the severity of skin lesions, and the psychological and social aspects of the disease. Potential targets include the management of anxiety, depression, and stress and enhancement of patients' sense of control over the disease and its consequences.

The results of the current study demonstrated that the most important demographic factor related to baseline QOL was psoriasis duration, SRSS, stress, and depression. Duration of more than 10 years and SRSS were also significantly associated with baseline WHOQOL-BREF scores. Patients who had longer disease duration reported less impairment of HRQOL at baseline. On the contrary, disease duration of more than 10 years showed negative impact on HRQOL score changes. A likely explanation is that individuals who suffered the disease for more than 10 years may be less emotionally affected by interpersonal difficulties; they may also have learned to cope better with certain aspects of living with psoriasis, and may have experienced less change than subjects who had the disease for less than 10 years. But a longer history of psoriasis demonstrated significantly less change in HRQOL. This is explained by patients who have suffered psoriasis for longer durations, who have realized the chronic prognosis of psoriasis and worried that the condition will recur. SRSS was a significant predictor of baseline HRQOL, as measured by WHOQOL-BREF, and change in the overall impact of psoriasis on HRQOL as measured by WHOQOL-BREF and Skindex-29. This finding was consistent with other studies that suggested self-reported general health was a significant and independent risk factor in the assessment of HRQOL26. Previous studies have shown that approximately half of the subjects were found to be depressed and anxious with the diagnosis of psoriasis27, and that psoriasis patients suffered higher rates of depression and body cathexis problem28. In the current study, depression and stress had an impact on psoriasis at baseline. Depression and stress may be a direct burden of psoriasis. The chronic stress associate with having to cope with psoriasis contributes to reduced HRQOL. Higher rates of depression also showed negative impact on HRQOL.

Sex, educational level, comorbidities, and marital status were not significantly associated with any change in HRQOL in our study. In contrast, a previous study has shown women to be more likely than men to report impairment of QOL29. Women experience greater interference with their lives with stress and worry. When patients need to expose their bodies around swimming pool or public showers, or live under conditions that do not provide appropriate privacy, women may feel ashamed and embarrassed more than men. In another study, patients with psoriasis who reported more severe symptoms were less likely to be married30. It is possible that the emotional support associated with having a partner is responsible for the reduced impairment of psoriasis-related QOL. It is, however, still unclear of their effect and further studies are needed.

Clinical trials most often used Dermatology Life Quality Index or Psoriasis Disability Index to measure QOL19. Although very few trials used a single QOL instrument, others used multiple instruments for QOL measurement. Although the exact reason for using more than one instruments for QOL was not mentioned in these studies, it may have been done to either compare measures, or because no single measure was considered to be superior over the other, with each offering a different aspect to QOL measurement. We used one general health status instrument and one dermatology-specific instrument. Based on this study, Skindex-29 is a responsive measure of psoriasis-specific outcomes that captures more comprehensively the impact of clinical symptoms on patient well-being. Although additional methodological studies are needed to compare and improve our understanding of the instruments, Both et al.2 recommended the Skindex-29 as the instruments of choice for dermatology.

There are several limitations to the present analysis. The first relates to the sample size and patient selection. Because the sample is a convenience sample of patients treated at a single site, it may not fully represent the population with psoriasis. In addition, not every patient had a complete baseline and follow-up HRQOL assessment. These missing cases may have affected the outcomes. Second, the severity of psoriatic lesions in study participants was mild nature. In our study, at baseline, the mean PASI scores were 9.1±7.0, yet the scale range was from 0 to 72 and, generally, patients were classified as having mild/moderate (PASI≤10) or severe (PASI>10) psoriasis31. The results, therefore, may have reflected a floor effect because of the mild/moderate nature of the psoriasis. Future study, which recruits patients with more severe disease at baseline, may be needed to examine the impact of QOL in psoriasis more thoroughly. Third, behavior such as alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and use of tranquilizers, sleeping pills, and antidepressants could have affected HRQOL, and these behaviors could be risk factors for psoriasis. Therefore, the extent to which these factors were reflected in QOL impairment and disease severity remains unelucidated. Fourth, assessment of other diseases in the comparison group could not be made with a standard tool, such as PASI, because it was consisted of a heterogenous mix of skin diseases. This is an inevitable bias of this study. Fifth, 16 weeks is a relatively short period from the prognosis of psoriasis and there was no consideration for seasonal control group in psoriasis. Finally, this study compared the psoriasis QOL and other skin diseases due to small number of participated patients suffering from dermatological disease other than psoriasis. Because the patients with psoriasis show more negative QOL than those with verruca or fungal infection, it could have an impact on the results.

Despite these caveats, our results confirm that psoriasis impacts HRQOL more negatively than the impact of other skin disease, and treatment are effective in improving generic HRQOL, dermatology-specific HRQOL, anxiety, depression, and stress levels. Psoriasis may become more burdensome in certain groups of patients who have long disease duration, higher SRSS, stress, and depression. The negative impact is on the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of QOL and can be greater than that created by other skin diseases. Therefore, effective treatment of psoriasis must focus on the multiple facets of this illness, including debilitating psychological, social, and environmental aspects.

References

- 1.Naldi L. Health-related quality of life: from health economics to bedside? Dermatology. 2007;215:273–276. doi: 10.1159/000107619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Both H, Essink-Bot ML, Busschbach J, Nijsten T. Critical review of generic and dermatology-specific health-related quality of life instruments. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2726–2739. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shumaker SA, Naughton MJ. The international assessment of health-related quality of life. In: Shumaker SA, Berzon RA, editors. The international assessment of health-related quality of life: theory, translation, measurement, and analysis. New York: Rapid Communications; 1995. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahl J, Hämäläinen H, Sintonen H, Simell T, Arinen S, Simell O. Health-related quality of life in type 1 diabetes without or with symptoms of long-term complications. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:427–436. doi: 10.1023/a:1015684100227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang R, Zhao Y, He X, Ma X, Yan X, Sun Y, et al. Impact of hypertension on health-related quality of life in a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Public Health. 2009;123:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleischmann KE, Orav EJ, Lamas GA, Mangione CM, Schron EB, Lee KL, et al. Atrial fibrillation and quality of life after pacemaker implantation for sick sinus syndrome: data from the Mode Selection Trial (MOST) Am Heart J. 2009;158:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Djärv T, Blazeby JM, Lagergren P. Predictors of postoperative quality of life after esophagectomy for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1963–1968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moser DK, Yamokoski L, Sun JL, Conway GA, Hartman KA, Graziano JA, et al. Improvement in health-related quality of life after hospitalization predicts event-free survival in patients with advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15:763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlay AY, Coles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:236–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min SK, Kim KI, Lee CI, Jung YC, Suh SY, Kim DK. Development of the Korean versions of WHO quality of life scale and WHOQOL-BREF. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:593–600. doi: 10.1023/a:1016351406336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen T, Bertenthal D, Sahay A, Sen S, Chren MM. Predictors of skin-related quality of life after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1386–1392. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.11.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn BK, Lee SJ, Namkoong K, Chung YL, Lee SH. The Korean version of Skindex-29. Korean J Dermatol. 2004;42:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. The Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory: a preliminary index of psoriasis-related stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:240–243. doi: 10.2340/0001555575240243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yook SP, Kim ZS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck anxiety inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997;16:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn HM, Yum TH, Shin YW, Kim KH, Yoon DJ, Chung KJ. A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory in Korea. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1986;25:487–500. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhosle MJ, Kulkarni A, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Griffiths CE. Psychologic factors in psoriasis: consequences, mechanisms, and interventions. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:681–694. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearce DJ, Singh S, Balkrishnan R, Kulkarni A, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. The negative impact of psoriasis on the workplace. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:24–28. doi: 10.1080/09546630500482886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fava GA, Perini GI, Santonastaso P, Fornasa CV. Life events and psychological distress in dermatologic disorders: psoriasis, chronic urticaria and fungal infections. Br J Med Psychol. 1980;53:277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1980.tb02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al'Abadie MS, Kent GG, Gawkrodger DJ. The relationship between stress and the onset and exacerbation of psoriasis and other skin conditions. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:199–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, McElhone K, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. Successful treatment of psoriasis improves psoriasis-specific but not more general aspects of patients' well-being. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1219–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unaeze J, Nijsten T, Murphy A, Ravichandran C, Stern RS. Impact of psoriasis on health-related quality of life decreases over time: an 11-year prospective study. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1480–1489. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fried RG, Friedman S, Paradis C, Hatch M, Lynfield Y, Duncanson C, et al. Trivial or terrible? The psychosocial impact of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb03588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devrimci-Ozguven H, Kundakci TN, Kumbasar H, Boyvat A. The depression, anxiety, life satisfaction and affective expression levels in psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:267–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zachariae R, Zachariae C, Ibsen H, Mortensen JT, Wulf HC. Dermatology life quality index: data from Danish inpatients and outpatients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:272–276. doi: 10.1080/000155500750012153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koo J. Population-based epidemiologic study of psoriasis with emphasis on quality of life assessment. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:485–496. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. Patients' strategies for coping with psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:177–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]