Abstract

Purpose

We examined the impact of radiation tumor bed boost parameters in early stage breast cancer on local control and cosmetic outcomes.

Materials and Methods

3,186 women underwent postlumpectomy whole-breast radiation with a tumor bed boost for Tis – T2 breast cancer from 1970 to 2008. Boost parameters analyzed included size, energy, dose, and technique. Endpoints were local control, cosmesis, and fibrosis. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate actuarial incidence, and a Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine independent predictors of outcomes on multivariate analysis (MVA). The median follow-up was 78 months (range 1–305).

Results

The crude cosmetic results were excellent in 54%, good in 41%, and fair/poor in 5% of patients. The 10-year estimate of an excellent cosmesis was 66%. On MVA, independent predictors for excellent cosmesis were use of electron boost, lower electron energy, adjuvant systemic therapy, and whole breast IMRT. Fibrosis was reported in 8.4% of patients. The actuarial incidence of fibrosis was 11% at 5 years and 17% at 10 years. On MVA, independent predictors of fibrosis were larger cup size and higher boost energy. The 10-year actuarial local failure was 6.3%. There was no significant difference in local control by boost method, cut-out size, dose or energy.

Conclusion

Likelihood of excellent cosmesis or fibrosis are associated with boost technique, electron energy, and cup size. However, because of high local control and rare incidence of fair/poor cosmesis with a boost, anatomy of the patient and tumor cavity should ultimately determine the necessary boost parameters.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Radiation Therapy, Radiation Boost

INTRODUCTION

Prospective randomized studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of a tumor bed boost in reducing the risk of local recurrence in conjunction with whole breast radiation for early stage invasive breast cancer (1, 2). A boost has also been shown to be associated with a decreased risk of local recurrence for patients with DCIS compared to whole breast radiation alone or no radiation (3). An international survey of Radiation Oncologists in 2001–2002 showed that 85% of American and 75% of European respondents would deliver a boost even with negative margins after whole breast irradiation (4). Current guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) suggest that a boost may not be required in all patients (5). This reflects the understanding that the magnitude of the benefit of the boost may be smaller in some subgroups of patients. The consensus guidelines for 2009 indicate that a boost is recommended for patients aged < 50 years, positive axillary nodes, positive lymphovascular space invasion, and/or close/positive resection margins – a boost in other low risk groups is considered optional but often given in clinical practice.

The risk to benefit ratio for the boost needs to be considered for each patient. The risks of a tumor bed boost include the potential for increased acute or long-term toxicity, cost, and additional treatment time. In both prospective randomized studies in invasive breast cancer testing the use of a sequential boost after whole breast radiation, the addition of the boost increased the incidence of late effects such as telangiectasias and fibrosis (1, 2).

There is little information on how the parameters of a radiation boost may impact upon the local control or risk of complications from the boost itself. The radiation boost may be given with photon beam or electron teletherapy techniques. Selection of treatment technique, energy, field size, and dose are variables that are dependent upon the individual patient and anatomic factors identified during simulation. Our purpose was to examine outcomes of local control, cosmesis, and fibrosis after whole breast radiation with a radiation boost with specific attention to the technical parameters used for the boost.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The study population consisted of 3,186 consecutive women with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy from 1970 – 2008. Inclusion criteria included: American Joint Committee on Cancer stages 0, I, or II breast cancer (6); radiation therapy at the Fox Chase Cancer Center; completed radiation therapy; lumpectomy; tumor stages Tis-T2; whole breast irradiation; receiving an additional tumor bed boost. Exclusion criteria included: male breast cancer; T3-T4 disease; stage IV disease; mastectomy; partial breast irradiation. Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and treatment-related information were entered prospectively into a database that was maintained and updated by a single data manager. The collection, storage, and retrieval of data were all done in compliance with the hospital’s Institutional Review Board and the Health Insurance Privacy and Portability Act.

All patients were treated with whole-breast radiation (46–50 Gy), with or without regional nodal radiation. Whole-breast radiation therapy consisted of conventional photon tangents earlier in the study period, while the majority of patients in later years received photon IMRT. In general, conventional radiation consisted of medial and lateral tangential fields covering the clinically palpable breast tissue with margin (7). Patients were placed in an alpha-cradle cast on a 10–20% wedged breast board for set-up reproducibility. Standard field borders are midline, 2 cm inferior and lateral to the breast tissue, and the clavicle or more superior to encompass the breast tissue. A 6 MV linear accelerator was used in most patients, 10 MV or 18 MV modified by a beam spoiler were used in some cases of large patient separation to improve dose homogeneity. The isodose distributions were optimized in the central axis by means of physical or virtual wedges. The IMRT technique consisted of a combination of open and segmented tangential fields using volume-based inverse dose planning and step-and-shoot beam delivery (8). Patients underwent simulation with a dedicated CT scanner to define the clinical target volume (CTV) including the palpable breast tissue and normal structures. Patients were placed in an alpha-cradle cast on a 10–20% wedged breast board for set-up reproducibility. The physician defined the CTV as the palpable breast tissue anterior to the chest wall to within 5 mm of the skin, and with a margin of 2 cm in the superior, inferior, and lateral directions. To facilitate the transition to IMRT and to make as valid a comparison as possible, the definition of the CTV by the physician, patient positioning, tangential beam orientation, and field sizes were kept the same as possible as those used for the previous conventional tangential photon technique used at our institution. Inverse dose planning was used to create an optimized dose distribution throughout the planning target volume (PTV) with dose constraints placed on normal lung and heart (for left –sided patients only) volume.

All patients received a supplemental boost to the tumor bed of 10–18 Gy. The boost dose was generally determined by the dose given to the whole breast, extent and number of surgical resections, and the final margin status. In general, the total dose to the tumor bed was a median of 60 Gy for a negative margin, 64 Gy for a close margin, and 66 Gy for a positive final margin. Technical information about the boost recorded in the database included dose, field size, beam energy, and technique (photon or electron). The selection of field sizes for the boost and energy chosen for depth of coverage were determined by the technology available during the study period. In early years of the study, boost size and depth was determined by placement of surgical clips and fluoroscopic simulation techniques (9–11). In later years, the dimensions of the boost and depth of coverage were determined by surgical clips as well as CT scan based simulation techniques (7, 12). In order to minimize missing data on the radiation boost, a separate retrospective review of charts and portal films was conducted in order to capture this information for all patients in early years of the study period when not entered into the database prospectively. Boost size of the electron cut-outs used to modify the square output field of the electrons was recorded in most patients. For patients with photon boosts, where information on field size and custom blocking was not available, boost size was considered unknown.

The primary endpoints of this study were local control, breast cosmesis, and fibrosis. Local control was defined as recurrence in the ipsilateral breast with or without regional nodal recurrence. Cosmetic result after radiation was scored by the commonly used four-point scale (excellent, good, fair, poor) (13). Cosmesis was coded from the patient’s perspective when available from the treatment record or intake questionnaires at each follow-up visit. The physician’s cosmetic score was used when a patient rating was not available. The database does not include a distinction between these two, so that retrospective analysis of physician versus patient cosmetic scoring was not possible. Fibrosis was diagnosed clinically by physician breast exams during routine follow-up visits and not confirmed by biopsy unless there was a suspicion for recurrence. The department policy of patient follow-up after treatment is generally every 6 months for 5 years after radiation and then annually. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to estimate the 5 and 10-year actuarial incidence of excellent cosmesis and fibrosis. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to look for independent predictors of each endpoint.

RESULTS

Patient demographics of 3,186 patients are shown in Table 1. The median follow-up time is 78 months (mean 90.3 months, range 1–305 months). The median and mean age is 58 years old (range 20–91 years old). The median tumor size was 1.4 cm (range 0.1 – 5.0 cm).

Table 1.

Patient demographics of 3,186 patients treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation.

| Characteristic | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3186 | 100 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 35 | 108 | 3 |

| 36–40 | 144 | 5 |

| 41–50 | 762 | 24 |

| 51–60 | 805 | 25 |

| > 60 | 1367 | 43 |

| Menopausal Status | ||

| Premenopausal | 846 | 27 |

| Perimenopausal | 158 | 5 |

| Postmenopausal | 2182 | 68 |

| Pathologic T Stage | ||

| Tis | 425 | 13 |

| T1 | 2160 | 68 |

| T2 | 601 | 19 |

| Histology | ||

| DCIS | 425 | 13 |

| Inv ductal | 2313 | 73 |

| Inv lobular | 268 | 8 |

| Other | 180 | 6 |

| Pathologic N Stage | ||

| N0 | 2507 | 79 |

| N1-3 | 531 | 16 |

| N4+ | 148 | 5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 2889 | 91 |

| Black | 230 | 7 |

| Other | 67 | 2 |

| Final Pathologic Margin | ||

| Negative | 2411 | 76 |

| Positive | 109 | 3 |

| Close (≤ 2 mm) | 386 | 12 |

| LCIS only | 84 | 3 |

| Unknown | 196 | 6 |

| Systemic Therapy | ||

| Chemotherapy alone | 448 | 14 |

| Both chemo and tam | 495 | 16 |

| Tam alone | 971 | 30 |

| No systemic | 1272 | 40 |

Cosmesis

Of 3186 patients, 2567 patients had data available for a cosmetic assessment. The crude cosmetic result at time of last recorded patient follow-up was excellent in 54% (1,382), good in 41% (1044), and fair/poor in 5% (126 and 13, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Crude results for cosmesis at last follow-up for 2,567 patients treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation. Numbers are percentages (actual patient numbers in parentheses).

| Characteristic | All Pts. | Excellent | Good | Fair/Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Results | 100 (2567) | 54(1382) | 41(1044) | 5(n=139) |

| Cup Size | ||||

| A | 5 (135) | 59 (80) | 39 (52) | 2 (3) |

| B | 29 (731) | 57 (416) | 36 (265) | 7 (48) |

| C | 26 (669) | 52 (349) | 43 (284) | 5 (36) |

| D/E | 15 (396) | 50 (197) | 45 (179) | 5 (20) |

| Unknown | 25 (636) | 53 (340) | 42 (264) | 5 (32) |

| Boost Method | ||||

| Electron | 97 (2495) | 55 (1360) | 40 (1009) | 5 (124) |

| Photon | 3 (72) | 30 (22) | 49 (35) | 21 (15) |

| Boost Energy | ||||

| 6–10 MeV | 30 (762) | 61 (468) | 36 (278) | 3 (22) |

| 12–16 MeV | 51(1316) | 52 (683) | 43 (567) | 5 (66) |

| 18–21 MeV | 16 (410) | 52 (212) | 40 (165) | 8 (35) |

| 6 MV | 1 (25) | 20 (5) | 48 (12) | 32 (8) |

| 10 MV | <1 (13) | 23 (3) | 54 (7) | 23 (3) |

| 18 MV | <1 (3) | 67 (2) | 33 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 1 (38) | 32 (12) | 50 (19) | 18 (7) |

| Boost Dose | ||||

| ≤ 10 Gy | 10 (250) | 64 (159) | 32 (80) | 4 (11) |

| 11–16 Gy | 58 (1483) | 54 (805) | 41 (609) | 5 (68) |

| > 16 Gy | 32 (834) | 50 (418) | 43 (355) | 7 (60) |

| Boost Size | ||||

| 4–6 cm. | 35 (908) | 61 (554) | 36 (326) | 3 (28) |

| 7–8 cm. | 41 (1053) | 53 (553) | 42 (448) | 5 (52) |

| > 8 cm. | 10 (253) | 49 (124) | 45 (114) | 6 (15) |

| Unknown | 14 (353) | 43 (152) | 44 (157) | 13 (44) |

| Whole Breast Technique | ||||

| Conventional | 85 (2174) | 52 (1119) | 42 (920) | 6 (134) |

| IMRT | 15 (393) | 67 (264) | 32 (124) | 1 (5) |

| Tumor Location | ||||

| Outer | 56 (1425) | 56 (803) | 39 (558) | 5 (63) |

| Inner | 20 (512) | 50 (255) | 45 (231) | 5 (26) |

| Central | 20 (512) | 52 (265) | 40 (204) | 8 (42) |

| Subareolar | 4 (118) | 50 (59) | 43 (51) | 7 (8) |

| Systemic Therapy | ||||

| Chemo alone | 14 (353) | 52 (181) | 43 (153) | 5 (17) |

| Both chemo and Tam | 15 (387) | 55 (213) | 40 (155) | 5 (19) |

| Tam alone | 30 (763) | 53 (406) | 41 (310) | 6 (47) |

| No systemic | 41 (1064) | 55 (582) | 40 (426) | 5 (56) |

For patients with an excellent cosmetic result, on univariate analysis the following significant differences were seen by patient or treatment-related characteristics: boost method (55% for electron boost compared to 30% for photon boost); boost dose (64% for ≤ 10 Gy compared to 50% for > 16 Gy); boost size (61% for 4–6 cm compared to 49% for > 8 cm and 43% for unknown/photon boost); use of IMRT for the whole breast treatment (67% for IMRT compared to 52% for conventional radiation) (Table 2). There was a nonsignificant trend for decreasing incidence of an excellent cosmetic result by cup size (59% for A cup compared to 50% for D/E cup), and boost energy (61% for 6–10 MeV compared to 52% for higher electron energy). There were no significant differences in the percentages of excellent cosmetic results between patients by the location of the tumor bed (50% – 56%) or use of adjuvant systemic therapies (52% chemotherapy, 53% tamoxifen, 55% both, and 55% none).

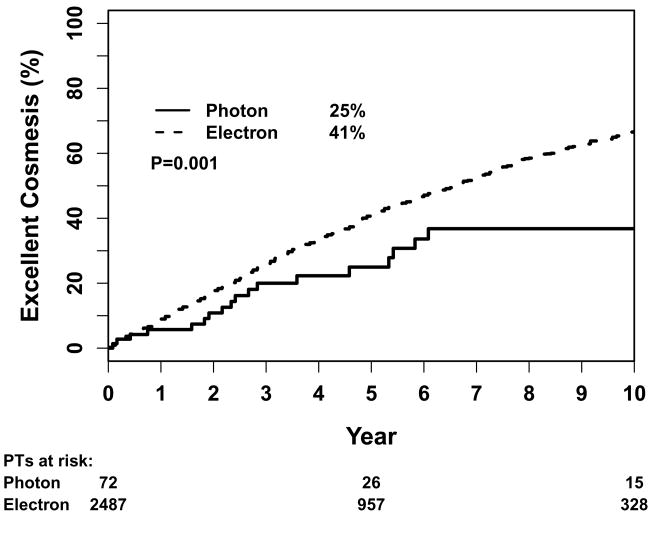

The 10-year actuarial estimate of having an excellent cosmetic outcome was 66% for all patients. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier estimation of percentage of patients with excellent cosmesis by method of boost treatment. There was a significant difference according to boost method, with more patients having an excellent cosmetic result with the use of electrons (67%) compared to photons (37%) (P=0.001). There were more patients with an excellent cosmetic result with a boost dose ≤ 10 Gy compared to > 16 Gy (73% versus 60%, p=0.0001). The 10-year percentages were 65% with use of chemotherapy, 71% with tamoxifen only, 77% for use of both, and 60% with no systemic therapy (p<0.0001). The 5-year percentages of excellent cosmesis was 96% with whole breast IMRT compared to 33% for conventional radiation (<0.0001). Smaller cut-out size was a borderline predictor of excellent cosmetic outcome (P=0.05), but this increased in level of significance when unknown size (which includes photon boost) was included in the analysis (P<0.0001). Neither boost energy nor surgical resection site of the tumor were associated with a significant difference in the univariate analysis.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimation of 5-year percentage of patients with excellent cosmesis by method of boost treatment.

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate analysis. Independent predictors of an excellent cosmetic result were use of electron boost, lower electron boost energy, adjuvant systemic therapy, and whole breast IMRT.

Table 3.

Results of significant independent predictors of excellent cosmetic outcome and fibrosis in Cox proportional hazard model.

| Variable (only significant factors shown) | Excellent Cosmesis Hazard Ratio (95% C.I.) | p value | Fibrosis Hazard Ratio (95% C.I.) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cup Size | 1.002 (0.919–1.092) | 0.97 | 1.267 (1.049–1.532) | 0.0143 |

| Boost Method Electron vs photon | 3.038 (1.312–7.033) | 0.0095 | 0.350 (0.080–1.562) | 0.1623 |

| Use of IMRT vs conventional radiation | 5.514 (4.451–6.830) | <0.0001 | 2.126 (1.352–3.342) | 0.0011 |

| Adjuvant Therapy | 0.0308 | 0.2167 | ||

| Chemo vs. none | 1.431 (1.117–1.834) | 0.0046 | 1.107 (0.657–1.866) | 0.7027 |

| Chemo/tam vs none | 1.279 (1.018–1.608) | 0.0348 | 1.083 (0.655–1.793) | 0.7552 |

| Tam vs none | 1.102 (0.921–1.318 | 0.2878 | 1.443 (1 – 2.083) | 0.05 |

| Boost Energy | 1.067 (1.025–1.112) | 0.0017 | ||

| 12–16 vs. 6–10 MeV | 0.770 (0.650–0.913) | 0.0026 | ||

| 18–21 vs. 6–10 MeV | 0.699 (0.556–0.878) | 0.0021 | ||

Fibrosis

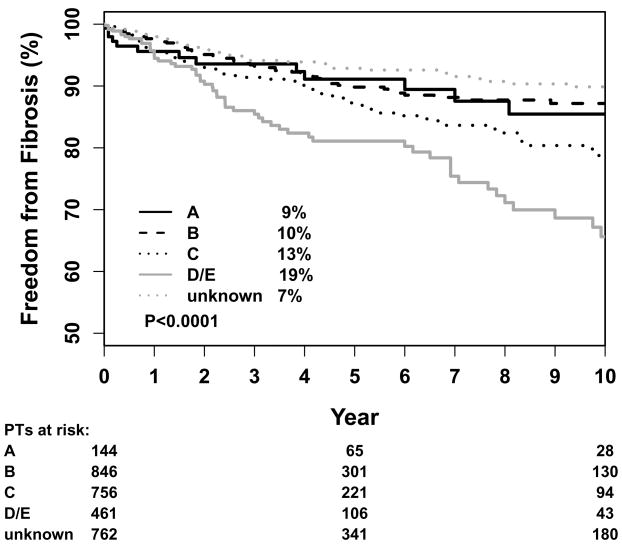

Of 3186 patients, the crude incidence of fibrosis based on physician clinical examination at time of last recorded follow-up was 273 patients or 8.4% (Table 4). The actuarial incidence was 11% at 5 years and 17% at 10 years.

Table 4.

Incidence of fibrosis in 3186 patients treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation with or without systemic therapy.

| Crude | Actuarial | Actuarial | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | # | # (%) | 5 years | 10 years | p value |

| All patients | 3186 | 273 (8.6) | 11 | 17 | |

| Cup Size | <0.0001 | ||||

| A | 160 | 13 (8.1) | 9 | 15 | |

| B | 910 | 65 (7.1) | 10 | 13 | |

| C | 818 | 77 (9.4) | 13 | 21 | |

| D/E | 510 | 63 (12.4) | 19 | 34 | |

| Unknown | 788 | 55 (7.0) | 7 | 10 | |

| Boost Method | 0.7 | ||||

| Electron | 3087 | 263 (8.5) | 11 | 16 | |

| Photon | 99 | 10 (10.1) | 11 | 19 | |

| Boost Dose | 0.08 | ||||

| ≤ 10 Gy | 298 | 23 (7.7) | 8 | 15 | |

| 11 – 16 Gy | 1871 | 149 (8.0) | 10 | 15 | |

| > 16 Gy | 1017 | 104 (10.2) | 13 | 20 | |

| Boost Size | <0.0001 | ||||

| 4 – 6 cm | 1009 | 83 (8.2) | 11 | 16 | |

| 7 – 8 cm | 1269 | 125 (9.9) | 15 | 25 | |

| > 8 cm | 320 | 34 (10.6) | 20 | 29 | |

| Unknown | 588 | 31 (5.3) | 1 | 2 | |

| Boost Energy | <0.0001 | ||||

| 6 – 10 MeV | 943 | 53 (5.6) | 7 | 11 | |

| 12 – 16 MeV | 1631 | 152 (9.3) | 12 | 17 | |

| 18 – 21 MeV | 526 | 59 (11.2) | 16 | 32 | |

| Whole-breast Method | <0.0001 | ||||

| IMRT | 552 | 43 (7.8) | 20 | -- | |

| Conventional | 2634 | 230 (8.7) | 10 | 15 | |

| Location | 0.7 | ||||

| Inner | 656 | 63 (9.6) | 10 | 16 | |

| Outer | 1768 | 145 (8.2) | 13 | 17 | |

| Central | 626 | 52 (8.3) | 10 | 17 | |

| Subareolar | 136 | 13 (9.6) | 11 | 13 | |

| Adjuvant Systemic Therapy | <0.0001* | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 266 | 40 (15.0) | 9 | 17 | |

| Tamoxifen | 802 | 98 (12.2) | 15 | 28 | |

| Both | 363 | 41 (11.3) | 14 | 20 | |

| None | 761 | 94 (12.4) | 8 | 10 |

On univariate analysis, the incidence of fibrosis increased by increasing size of the electron boost field size. Additionally, the incidence of fibrosis was also associated with three factors intrinsically related to the size of the patient: whole breast cup size, increasing energy of the boost, and whole-breast photon energy (large breasted patients tend to need higher treatment energies to improve dose homogeneity). On MVA, the only independent predictors of fibrosis were larger cup size and higher boost energy (Table 3). Adjuvant systemic therapy was associated with a greater risk of fibrosis of borderline significance only for use of tamoxifen compared to no systemic therapy on MVA (P=0.05). There was no difference seen with use of chemotherapy. Use of IMRT had a similar crude incidence of fibrosis compared to conventional radiation - 8% for IMRT and 9% for conventional radiation. However, both coding of fibrosis and change from conventional to IMRT began around same time (2003–4), so that there are marked different lengths of follow-up between groups. This discrepancy in follow-up time created a difference in the actuarial 5-year incidence of fibrosis so that IMRT was an independent predictor of fibrosis at 5 years. Surgical site, boost dose, and boost method (electron vs. photon) were not associated with incidence of fibrosis.

Local Control

The 10-year actuarial local failure was 6.3%. There was no significant difference in local control by any of the characteristics of the boost tested including method (photon versus electron), field size, dose or energy.

DISCUSSION

The use of a tumor bed boost is commonly recommended after breast-conserving surgery and postoperative whole breast irradiation. The rationale for giving a higher dose boost to the tumor bed includes pathologic studies showing a high incidence of residual disease close to the excision cavity, and a high percentage of recurrences in close proximity to the excision site after postoperative radiation. However, a boost is not considered mandatory in all patients. The randomized prospective trial by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP-06) of breast-conserving surgery and postoperative radiation did not include a boost yet showed equal long-term survival as mastectomy. In two prospective randomized studies in invasive breast cancer specifically studying the impact of a boost, the use of a boost after whole-breast radiation reduced the risk of local recurrence even in patients with negative resection margins (1, 2). Current guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) suggest that a boost may not be required in all patients (5). This reflects the understanding that the magnitude of the local control benefit of the boost may be small in some subgroups of patients. The NCCN consensus guidelines for 2009 indicate that a boost is recommended for patients aged < 50 years, positive axillary nodes, positive lymphovascular space invasion, and/or close/positive resection margins. A boost in other low risk groups is considered optional.

This study has taken a more detailed look at patient outcomes related to the treatment-related and technical factors of the radiation boost. These factors include boost field size, dose, energy and method. We did not observe a worse cosmesis or a higher incidence of fibrosis by higher field size. The size of the boost and required depth of coverage are determined by the extent of the surgical resection. Surgical clips placed at the time of surgery are used to improve coverage of the tumor bed compared to use of the lumpectomy incision alone (9, 10, 14). In early years of the study, methods of determining depth were based upon techniques of fluoroscopic simulation (11). The optimal coverage of the tumor bed is now determined by CT scanning (7, 15, 16). Our study suggests that coverage of even large tumor beds can be achieved without observed differences in long-term cosmetic outcome.

However, there are indications from our study that large breast size may be associated with a lower likelihood of patients indicating they had an excellent cosmetic result and increase in fibrosis. We found that larger cup size serves as an independent predictor of complications, and that women with a relatively larger breast size receiving a boost have a two-fold chance of developing fibrosis over the entire study population at 10 years (34% for D/E cup vs. 17% for all patients). We did observe a lower incidence of excellent cosmetic result in women treated with photon boost versus electrons. We also observed that there was an increased association of excellent cosmetic result and less reported fibrosis with a lower boost energy. Tumor beds in a deeper location, generally more than 5 cm from the skin surface, may not be adequately covered by electron beam or would require the highest electron beam energies (higher beam energy is associated with higher depth of penetration). These women tend to be the ones treated with photons or high electron beam energy, and would be those women with larger breast size. Also related to this is the finding that larger cup size and higher boost energy were associated with increased risks of fibrosis. Complications in larger-breasted women may be able to be minimized in the future by improved methods of achieving dose homogeneity. Photon boosts in early years of the study prior to 2003 were generally designed with 2D planning. Photon boosts planned in this method may be associated in general with a larger average field size than electrons during that study period to include greater margins for respiratory motion, set-up variability and penumbra. Improved methods of 3D treatment planning of the boosts and more conformal methods of targeting may lead to improved results with photon beam boosts.

We also studied the impact of factors related to the whole-breast technique used for treatment before the boost. The use of IMRT began to replace conventional radiation in this study population form 2003 – 2004. IMRT is associated with improved dose homogeneity and reduced acute skin toxicity compared to conventional radiation (17–20). We observed an improvement in the percentages of an excellent cosmetic result for women receiving IMRT before their boost. We expected the use of IMRT to be associated with a decreased likelihood of fibrosis, based upon a previous randomized prospective trial showing decreased fibrosis at 5 years compared to conventional radiation (17). While the crude incidence of fibrosis was 8% for IMRT and 9% for conventional radiation, the actuarial incidence was approximately 2-fold higher for IMRT. We believe this is due to the marked differences in length of follow-up. The coding of fibrosis in the breast cancer database began in approximately 2003 when there was implementation of a new protocol for collection and storage of data complaint with HIPAA regulations. This was also coincidentally the time of change from conventional to IMRT. There is essentially no follow-up greater than 5 years in IMRT patients in this study, so that there are markedly different lengths of follow-up for IMRT patients when compared to patients treated with conventional therapy and a resulting distortion in the actuarial 5- and 10-year calculations of fibrosis. Further follow-up is needed to confirm in this population of patients the long-term incidence of fibrosis compared to conventional radiation.

We found that the use of systemic chemotherapy was not significantly associated with worse long-term cosmetic outcome or fibrosis. This may be due to the use of sequential rather than concurrent chemotherapy in these patients. The 10-year estimate of having an excellent cosmetic result was significantly different on univariate analysis, with trends in favor of systemic therapy compared to no systemic therapy (65% with use of chemotherapy, 77% for use of chemotherapy and tamoxifen, and 60% with no systemic therapy) but these differences were not significant on multivariate analysis. We did observe a higher incidence of fibrosis on physician breast examinations in follow-up of patients treated with tamoxifen compared to no systemic therapy but this was only of borderline significance (p=0.05) on MVA correcting for other variables (Table 3). Previous studies have not confirmed an increase in complications or worse cosmetic results with use of tamoxifen compared to no tamoxifen or concurrent with radiation compared to sequential (21, 22).

The 10-year actuarial local failure in this study of patients all treated with a radiation boost was 6.3%. This is comparable to the incidence of local recurrence observed with a boost in the large prospective randomized trial by the EORTC of 6.2%. We could not identify predictive factors for local control based upon variation in technique of the radiation boost. There were no significant differences in local control by radiation technique, field size, boost energy, or boost dose. This may be due to the close association between patient anatomy and tumor bed location with the resulting treatment plan and boost technique used to treat the patient. In other words, large breasted patients may have required higher energy, larger tumor beds may have required larger field sizes, and close or positive margins may have required a higher tumor bed boost dose. As long as the treatment plan resulted in hitting the target adequately, the specific differences in boost technique were not of consequence for local control.

Conclusion

Excellent cosmesis was associated with electron boost, lower electron boost energy, adjuvant systemic therapy and use of IMRT. Higher electron energy and larger cup size were associated with fibrosis. Longer follow-up is needed with IMRT to observe differences in fibrosis compared to conventional radiation. Because local control was high and the incidence of fair/poor cosmesis was low with a boost, anatomy of the patient and tumor cavity should ultimately determine the choice of boost parameters.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimation of 5-year percentage of patients with fibrosis by cup size.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cindy Rosser for her collection and management of the data for the study population.

Footnotes

Abstract presented at the scientific session of the 51st annual meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology, Chicago, IL, October 31 – November 5, 2009

Conflict of Interest Statement: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Romestaing P, Lehingue Y, Carrie C, et al. Role of a 10-Gy boost in the conservative treatment of early breast cancer: Results of a randomized clinical trial in Lyon, France. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:963–968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartelink H, Horiot J-C, Poortmans PM, et al. Impact of a Higher Radiation Dose on Local Control and Survival in Breast-Conserving Therapy of Early Breast Cancer: 10-Year Results of the Randomized Boost Versus No Boost EORTC 22881–10882 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3259–3265. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omlin A, Amichetti M, Azria D, et al. Boost radiotherapy in young women with ductal carcinoma in situ: a multicentre, retrospective study of the Rare Cancer Network. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:652–656. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70765-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceilley E, Jagsi R, Goldberg S, et al. Radiotherapy for invasive breast cancer in North America and Europe: Results of a survey. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [access date 3/9/2009];NCCN practice guidelines for breast cancer. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast.pdf.

- 6.American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer staging manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowble B, Freedman G. Cancer of the Breast. In: Wang CC, editor. Clinical Radiation Oncology: indications, techniques and results. 2. Wiley-Liss, inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li JS, Freedman GM, Price R, et al. Clinical implementation of intensity-modulated tangential beam irradiation for breast cancer. Med Phys. 2004;31:1023–1031. doi: 10.1118/1.1690195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machtay M, Lanciano R, Hoffman J, et al. Inaccuracies in using the lumpectomy scar for planning electron boosts in primary breast carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solin LJ, Danoff BF, Schwartz GF, et al. A practical technique for the localization of the tumor volume in definitive irradiation of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solin LJ, Chu JCH, Larsen R, et al. Determination of depth for electron breast boosts. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1915–1919. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das IJ, Cheng EC, Wurzer JC, et al. Impact of CT simulation for cone down electron treatment of breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:244. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris JR, Levene MB, Svensson G, et al. Analysis of cosmetic results following primary radiation therapy for stages I and II carcinoma of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:257–261. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90729-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington KJ, Harrison M, Bayle P, et al. Surgical clips in planning the electron boost in breast cancer: a qualitative and quantitative evaluation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34:579–584. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg H, Prosnitz RG, Olson JA, et al. Definition of postlumpectomy tumor bed for radiotherapy boost field planning: CT versus surgical clips. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hepel JT, Evans SB, Hiatt JR, et al. Planning the breast boost: comparison of three techniques and evolution of tumor bed during treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donovan E, Bleakley N, Denholm E, et al. Randomised trial of standard 2D radiotherapy (RT) versus intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) in patients prescribed breast radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pignol JP, Olivotto I, Rakovitch E, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of breast intensity-modulated radiation therapy to reduce acute radiation dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2085–2092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman GM, Anderson PR, Li J, et al. Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) decreases acute skin toxicity for women receiving radiation for breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:66–70. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000197661.09628.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman G, Li T, Nicolaou N, et al. Breast intensity modulated radiation therapy reduces time spent with acute dermatitis for women of all breast sizes during radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowble B, Fein DA, Hanlon AL, et al. The impact of tamoxifen on breast recurrence, cosmesis, complications, and survival in estrogen receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:669–677. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris EER, Christensen VJ, Hwang W-T, et al. Impact of Concurrent Versus Sequential Tamoxifen With Radiation Therapy in Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Breast Conservation Treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:11–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]