Abstract

Background

Purpose in life is thought to be associated with positive health outcomes in old age, but its association with disability is unknown.

Objective

Test the hypothesis that greater purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability, including impairment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living and mobility disability, among community-based older persons free of dementia.

Design

Participants were from the Rush Memory and Aging Project, a large longitudinal clinical-pathologic study of aging.

Setting

Retirement communities, senior housing facilities, and homes across the greater Chicago metropolitan area.

Measurements

All participants underwent baseline assessment of purpose in life and detailed annual clinical evaluations to document incident disability.

Results

The mean score on the purpose in life measure at baseline was 3.6 (SD=0.5, range: 2 to 5). In a series of proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, and education, greater purpose in life was associated with a reduced risk of disability in basic activities of daily living (HR=0.60, 95% CI 0.45, 0.81), instrumental activities of daily living (HR=0.56; 95% CI 0.40, 0.78), and mobility disability (HR=0.61, 95% CI 0.44, 0.84). These associations did not vary along demographic lines and persisted after the addition of terms to control for global cognition, depressive symptoms, social networks, neuroticism, income, physical frailty, vascular risk factors, and vascular diseases.

Conclusions

Among community-based older persons without dementia, greater purpose in life is associated with maintenance of functional status, including a reduced risk of developing impairment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living and mobility disability.

Keywords: purpose in life, activities of daily living, disability, functional status

Introduction

The identification of factors associated with a reduced risk of disability is a major public health priority, particularly given the high risk of disability in the already large and rapidly increasing aging population. Purpose in life is a psychological construct that has long been hypothesized to be associated with positive health outcomes but has received relatively little research focus[1–7]. Purpose in life refers to the tendency to derive meaning from life’s experiences and possess a sense of intentionality and goal directedness that guides behavior[8,9]. In cross-sectional analyses, purpose in life and a related construct referred to as “meaning in life” have been associated with positive psychological outcomes including happiness, satisfaction, and self-esteem, as well as aspects of physical functioning, including better sleep, more positive self-ratings of health, and lower levels of functional limitation[3,5,11–14]; the biologic basis of these associations remains unclear, but it is hypothesized that purpose in life may benefit health by promoting the efficient functioning of multiple physiologic (e.g., vascular and immune) systems. Prospective data on the association of purpose in life with health outcomes are limited; however, we recently reported that purpose in life is associated with a substantially reduced risk of mortality and Alzheimer’s disease among community-based older persons[9,10]. Although we are not aware of any prospective study that has examined the association of purpose in life with the risk of developing disability in older persons, the association of the related construct of meaning in life with disability and the predictive association of purpose with other outcomes suggests that purpose in life may have important prognostic implications for health in old age.

We used data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project[15], an ongoing longitudinal epidemiologic study of aging, to test the hypothesis that purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability in a large group of community-based older persons free of dementia. Participants completed detailed baseline evaluations including assessments of purpose in life and annual detailed clinical evaluations that included documentation of disability for up to eight years. Purpose in life was operationally defined as a complex, multidimensional construct that reflects the trait-like tendency to derive meaning from life’s experiences and possess a sense of intentionality and goal directedness that guides behavior. Proportional hazards models were used to examine the association of purpose in life with the risk of disability, including impairment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living, as well as mobility disability. In subsequent models, we examined the influence of several potential confounders of the association between purpose in life and disability, including the level of global cognitive function, depressive symptoms, social networks, neuroticism, income, physical frailty, vascular risk factors, and vascular diseases.

Methods

Participants

Participants included older persons without dementia from the Rush Memory and Aging Project, an ongoing longitudinal clinical-pathologic study of common chronic conditions of old age[15]. Participants are residents of approximately 40 senior housing facilities in the Chicago metropolitan area. All undergo risk factor assessment, detailed annual clinical evaluations, and organ donation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center, and informed consent and an anatomical gift act were obtained as conditions of entry following a detailed presentation of the risks and benefits.

Details of the clinical evaluation have been described previously[8,9,15,16]. Briefly, the uniform structured baseline evaluation included medical history, neurological and neuropsychological examinations. Follow-up evaluations, identical to the baseline in all essential details, were conducted annually by examiners blinded to all previous data. At each evaluation, diagnostic classification was performed by an experienced clinician after a review of all available data[16]. The diagnosis of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease followed the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria, which require evidence of cognitive decline and impairment in at least two domains of cognition[17].

At the time of these analyses, 1150 participants had completed a baseline evaluation. Of those, 67 persons with dementia and 113 persons who died before first follow-up evaluation or had not yet reached their first follow-up evaluation were excluded, leaving 970 eligible participants. These persons completed an average of 4.6 annual evaluations (SD=1.7, range: 2–8).

Assessment of purpose in life

Purpose in life is a psychological construct that refers to the trait-like tendency to derive meaning from life’s experiences and possess a sense of intentionality and goal directedness that guides behavior. Purpose in life was assessed using a 10-item scale[8,9]derived from Ryff’s scales of Psychological Well-Being[6,7] in which participants rated their level of agreement with each item (e.g., I have a sense of direction and purpose in life, I am an active person in carrying out the goals I set for myself) on a five point scale, as previously described[8,9]. As previously reported[8], the Cronbach’s coefficient alpha on this scale was 0.73, indicating a moderate level of internal consistency[8]. For scoring, negatively worded items scores were flipped and item scores were averaged together to yield a total score for each participant (possible range=1–5), with higher scores indicating greater purpose in life. We previously reported correlations between purpose in life and depressive symptoms, neuroticism, and disability[8–10]. Notably, however, in our prior analyses, purpose in life was associated with longevity even after controlling for those covariates, suggesting that it is a relatively distinct psychological construct that has predictive validity for health outcomes[9].

Assessment of disability

Disability was assessed via three instruments. Basic activities of daily living were assessed using a modified version of the Katz Index[19], a self-report measure that assesses six activities: feeding, bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, and walking across a small room. Participants were given the following response choices with regard to their ability to perform each of the 6 activities: no help, help, unable to do. For the core analyses, participants who reported needing help on or an inability to perform one or more tasks were classified as being disabled, as is commonly done in the literature[15,30–32].

Instrumental activities of daily living were assessed using items adapted from the Duke Older Americans Resources and Services project[20], which assess eight activities: telephone use, meal preparation, money management, medication management, light and heavy housekeeping, shopping, and local travel. Participants were given the following response choices with regard to their ability to do each of the eight instrumental activities: no help, help, unable to do. Those who reported needing help on or an inability to perform one or more tasks were classified as being disabled.

Mobility disability was assessed using the Rosow-Breslau scale[21], which assesses three activities: walking up and down a flight of stairs, walking a half mile, and doing heavy housework like washing windows, walls, or floors. Participants were asked if they could perform each task without help, and those who reported being unable to do one or more were classified as being disabled.

Assessment of additional potential confounders

Data from the baseline evaluation were used to examine several potential confounders of the association of purpose and disability, including global cognition, depressive symptoms, neuroticism, income, physical frailty, vascular risk factors, and vascular diseases.

Cognitive function was assessed annually via a battery of 21 tests, as previously described[15,16]. Scores on 19 tests were used to create summary indices of global cognitive function. To compute the composite measure of global cognitive function, raw scores on each of the individual tests were converted to z-scores using the baseline mean and standard deviation of the entire cohort, and the z-scores of all 19 tests were averaged.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with a 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale[22,23]. Participants were asked whether they had experienced each of 10 symptoms in the past week, and the score was the number of symptoms reported.

Neuroticism, a personality trait described as the tendency to experience psychological distress, was measured using the neuroticism subscale of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory to assess personality[24]. Summary scores of the trait were computed, with higher scores indicating a higher level of neuroticism.

Social network size was quantified with standardquestions regarding the number of children, family, and friendsparticipants had and how often they interacted with them[15,25]. Socialnetwork size was the number of these individuals seen at leastonce a month, as reported elsewhere[15,25].

Summary scores indicating vascular risk burden (i.e., the sum of smoking, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, resulting in a score from 0–3 for each individual) and vascular disease burden (i.e., the sum of heart attack, congestive heart failure, claudication, and stroke, resulting in a score from 0–4 for each individual) were computed on the basis of self-report questions, clinical examination, and medication inspection, as previously described[16].

A composite measure of physical frailty based on five components (i.e., grip strength, timed walk, body composition, fatigue, and physical activity) was used in the present study, as previously described[42]. For this composite, grip strength was measured with the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer, gait was based on the time to walk eight feet, body composition was based on body mass index (BMI) = weight/height2, and fatigue was assesses via two questions derived from a modified version of the CES-D Scale. Physical activity was assessed using questions adapted from the 1985 National Health Interview Survey[32,15]; the activities included walking for exercise, gardening/yardwork, calisthenics/general exercise, bicycle riding, and swimming/water exercise, and the number of minutes/week spent engaging in each activity were summed. The five components used for the composite frailty measure were structured so that persons with low performance on 2 or more components were considered frail, to be consistent with prior literature[42].

Other variables used in the analyses included age (based on date of birth), sex, education (years of schooling completed), race, and current income. Current income was measured at baseline via a single question. Persons were asked to select one of 10 levels oftotal family income using the “show-card” method[15].

Data analysis

Pearson correlations were used to examine the bivariate associations between purpose in life and demographic variables, and t-tests were used to compare baseline characteristics; the a priori level of statistical significance was p<0.05. The association of purpose in life with disability was examined via a series of proportional hazards models for discrete (tied) data[25]; that is, because examinations are scheduled in an annual cycle, differences of a few months in the date of the first evaluation with disability correspond to the sequence in which participants were studied, not the sequence in which the participants developed disability. Thus, the time from baseline to the examination at which disability was first diagnosed was rounded to the nearest year. All models were adjusted for age, sex and education. In subsequent models, we added interaction terms for age, sex, and education to examine whether the associations of purpose in life with risk of disability varied along demographic lines. Finally, we repeated the core models with terms for several potential confounders of the associations between purpose and disability and conducted sensitivity analyses in which disability was defined more conservatively as two or more impairments on any given disability measure. Programming was done in SASR[26], and model validation was carried out using analytic and graphical techniques.

Results

Baseline characteristics and psychometric properties of purpose in life

Baseline characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. Scores on the measure of purpose in life ranged from 2–5 (mean=3.6), with higher scores indicating greater purpose. In unadjusted analyses, purpose in life was modestly associated with age (Pearson r=−0.25, df=968, p<0.0001) and education (Pearson r=0.27, df=968, p<0.0001); women reported lower purpose compared to men (t(df=968)= −2.77, p=0.006).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample (n=970).

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 80.2 (7.5) | 54 to 100 |

| Education | 14.4 (3.1) | 0 to 28 |

| % Female | 74.6 | |

| % white, non-Hispanic | 88.3 | |

| Purpose in life | 3.6 (0.5) | 2 to 5 |

| Katz scale | 0.2 (0.7) | 0 to 6 |

| IADL scale | 1.0 (0.5) | 0 to 8 |

| Mobility disability | 0.8 (1.0) | 0 to 3 |

| Global cognition | 0.1 (0.5) | −1.6 to 1.4 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.4 (1.8) | 0 to 9 |

| Neuroticism | 15.2 (7.1) | 0 to 44 |

| Social networks | 6.6 (5.8) | 0 to 66 |

| Vascular risk factors | 1.1 (0.8) | 0 to 3 |

| Vascular diseases | 0.4 (0.6) | 0 to 3 |

| Physical Frailty | 0.6 (0.6) | 0 to 4 |

Purpose in life and risk of developing disability in basic activities of daily living

To examine the association of purpose in life with the risk of developing disability in basic activities of daily living, we used a proportional hazards model for discrete (tied) data adjusted for age, sex, and education. This analysis was restricted to the 856 persons (88.2% of 970) who reported no disability on the Katz measure at baseline. Over a mean of 4.7 years of follow-up, 282 persons (32.9% of 856) became disabled. In the proportional hazards model, greater purpose in life was associated with a substantially reduced risk of developing disability in basic activities of daily living (HR=0.60, 95% CI 0.45, 0.81, Wald X2 (df=1)=11.41, p<0.001). Thus, as illustrated in Figure 1, a person with a high score on the purpose in life measure (score=4.2, 90th percentile) was nearly 2-fold more likely to remain free of disability than a person with a low score (score=3.0, 10th percentile).

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard of developing disability in basic activities of daily living for a participant with a high (dotted line) vs. low (solid line) level of purpose in life.

Next, because the association of purpose in life with disabilitymay vary along demographic lines, we repeated the analysis described above with additional terms for the interactions of age, sex, and education with purpose in life in separate models. No interactions were found. In addition, because cognition, negative affect (i.e., depressive symptoms), neuroticism, social networks, income, physical frailty, vascular risk factors, and vascular diseases may influence the associationof purpose in life with disability[27–29], we repeated the core model described above with terms to control for these covariates in separate models. The association of purpose in life with disability persisted even after adjustment for these covariates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of purpose in life with disability after adjustment for covariates.

| Covariate | IADLs: Hazard Ratio, 95% CI Wald X2 (df=1) | P-Value | Katz: Hazard Ratio, 95% CI Wald X2 (df=1) | P-Value | Mobility disability: Hazard Ratio, 95% CI Wald X2 (df=1) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global cognition | 0.63 (0.45, 0.89) 7.04 | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.49, 0.89) 10.58 | 0.006 | 0.67 (0.50. 0.91) 6.41 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.60 (0.43, 0.86) 8.01 | 0.005 | 0.70 (0.51, 0.95) 5.21 | 0.022 | 0.66 (0.48, 0.92) 6.12 | 0.013 |

| Neuroticism | 0.68 (0.47, 0.98) 4.16 | 0.030 | 0.66 (0.48, 0.91) 6.61 | 0.009 | 0.67 (0.47, 0.95) 5.06 | 0.023 |

| Social networks | 0.58 (0.41, 0.82) 9.78 | 0.002 | 0.61 (0.45, 0.82) 10.71 | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.49, 0.85) 9.74 | 0.002 |

| Income | 0.57 (0.42, 0.79) 11.47 | <0.001 | 0.58 (o.42, 0.79) 11.47 | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.40, 0.80) 10.25 | <0.001 |

| Physical Frailty | 0.59 (0.42, 0.84) 8.93 | 0.002 | 0.72 (0.54, 0.98) 11.35 | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.54, 0.97) 4.45 | 0.031 |

| Vascular risk factors | 0.56 (0.40, 0.80) 11.10 | <.001 | 0.61 (0.45, 0.81) 11.04 | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.45, 0.81) 11.04 | <0.001 |

| Vascular diseases | 0.56 (0.40, 0.78) 11.54 | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.45, 0.61) 11.13 | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.45, 0.81) 11.13 | <0.001 |

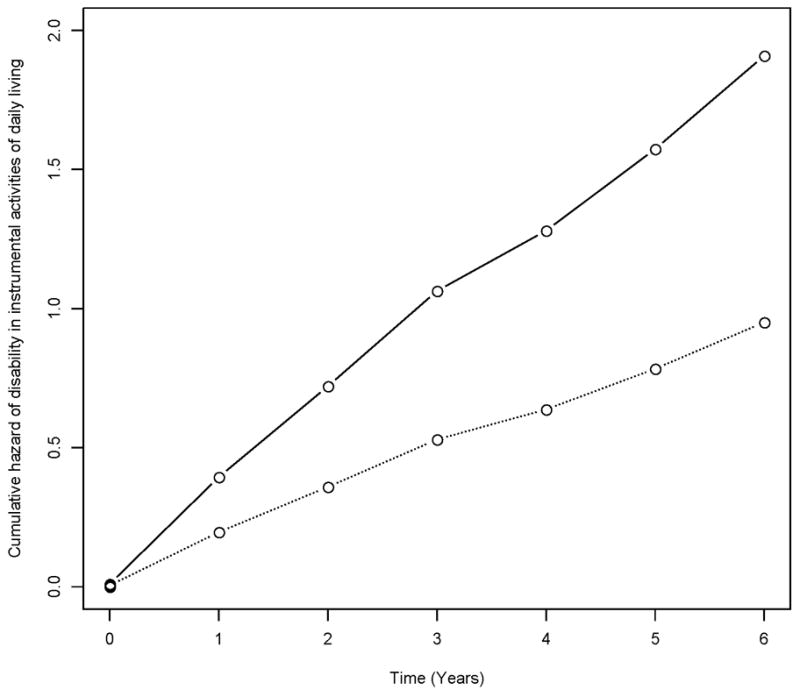

Purpose in life and risk of developing disability in instrumental activities of daily living

Next, to examine the association of purpose in life with the risk of developing disability in instrumental activities of daily living, we used a proportional hazards model for discrete (tied) data adjusted for age, sex, and education. This analysis was restricted to the 483 (49.8% of 970 persons) who reported no disability in instrumental activities of daily living at baseline. Over a mean of 4.8 years of follow-up, 278 persons (57.6% of 483) developed impairment in instrumental activities of daily living. In the proportional hazards model, greater purpose in life was associated with a substantially reduced risk of developing disability in instrumental activities of daily living (HR=0.56, 95% CI 0.40, 0.78, Wald X2 (df=1)=11.35, p<0.001)). Thus, as illustrated in Figure 1, a person with a high score on the purpose in life measure (score=4.3, 90th percentile) was about 2.0 times more likely to remain free of disability than a person with a low score (score=3.1, 10th percentile).

In subsequent analyses, we examined whether the association of purpose in life with disability on the measure of instrumental activities of daily living varied along demographic lines or could be accounted for by the potential confounders examined above. No interactions were found. Moreover, the association between purpose in life and disability persisted even after controlling for each of the covariates (Table 2).

Purpose in life and risk of developing mobility disability

Finally, we examined the association of purpose in life with the risk of developing mobility disability. This analysis was restricted to the 535 (55.2% of 970 persons) who reported no mobility disability at baseline. Over a mean of 4.8 years of follow-up, 291 persons (54.4% of 535) developed mobility disability. In the proportional hazards model, greater purpose in life was associated with a reduced risk of developing mobility disability (HR=0.61, 95% CI 0.44, 0.84, Wald X2 (df=1)=9.34, p=0.002). Thus, as illustrated in Figure 3, a person with a high score on the purpose in life measure (score=4.3, 90th percentile) was about 1.8 times more likely to remain free of disability than a person with a low score (score=3.1, 10th).

Figure 3.

Cumulative hazard of developing mobility disability for a participant with a high (dotted line) vs. low (solid line) level of purpose in life.

In subsequent analyses, we examined whether the association of purpose in life with mobility disability varied along demographic lines or could be accounted for by the potential confounders examined above. No interactions were found, and the association between purpose in life and mobility disability persisted even after controlling for each of the covariates (Table 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Finally, because disability can be defined in different ways, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which we repeated the core analyses examining the relation of purpose in life with the risk of disability on each measure with disability defined as the development of dependence in at least two activities (as opposed to one). The results of these analyses were comparable to the original models (HR for basic activities=0.62, 95% CI 0.44, 0.88, Wald X2 (df=1)=7.28, p=0.007); HR for instrumental activities=0.47, 95% CI=0.35, 0.64, Wald X2 (df=1)=23.95, p<0.001), HR for mobility disability=0.60, 95% CI=0.44, 0.83, Wald X2 (df=1)=9.51, p<0.001).

Discussion

In a large cohort of community-based older persons free of dementia, we found that greater purpose in life was associated with a substantially reduced risk of incident disability, including impairment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living and mobility disability. Our results were robust in that they were unchanged even after controlling for a wide variety of potential confounding variables, including global cognitive function, depressive symptoms, neuroticism, social networks, income, physical frailty, and vascular risk factors and diseases. Further, the association of purpose in life with disability persisted after varying the cut-off score used to define disability to make it more conservative. These findings suggest that having a sense of purpose in life is associated with maintenance of functional independence in old age.

Although we are not aware of any prior study that examined the association of purpose in life with the subsequent risk of developing disability, emerging data suggest that related psychological factors are associated with the development of disability in old age[31–35]. For example, neuroticism and harm avoidance have been associated with an increased risk of disability, and extraversion and conscientiousness have been associated with a reduced risk of disability[31–33]. Purpose in life is a psychological construct that has long been hypothesized to buffer against adverse health outcomes and that has been shown in cross-sectional studies to be associated with psychological health, including happiness, satisfaction, and self-acceptance[1–7]. This study extends recent findings from the same cohort showing that purpose in life was associated with a reduced risk of mortality and Alzheimer’s disease[9]. Together, these data suggest that purpose in life is associated with a number of important health outcomes and may suggest that a greater focus on positive psychological factors may provide new information regarding successful aging.

At present, the basis of the association of purpose in life with disability is unknown. One hypothesis is that purpose in life enhances health directly by contributing to the optimal functioning of multiple physiologic systems. Purpose in life is associated with some important disease biomarkers[36–39], including salivary cortisol, the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6r, HDL cholesterol, and waist-hip ratios. Given that vascular conditions and subclinical inflammation (i.e., CRP and IL-6) are associated with poorer physical function in older persons[40.41], purpose in life may be protective against disability via its beneficial effect on vascular health and immune function. In this study, however, controlling for vascular risk factors and diseases did not alter the relation of purpose in life with disability, suggesting that other mechanisms must be operating. Another possibility is that purpose in life influences engagement in health promoting behaviors and thus indirectly affects health. That is, older persons who have greater purpose may eat better, exercise more, and avoid harmful substances and behaviors compared to those with lower purpose, who may even become self-neglecting. Although we are aware of limited data on the extent to which purpose is related to health promoting behaviors, one study reported that a greater sense of purpose in life was associated with better breast health behavior in women[43]. Purpose in life may confer health benefits directly or indirectly, and future research is needed to determine how it operates.

The finding that purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of disability has important public health implications. In particular, these findings may suggest an important aspect of the assessment of older adults and provide a new target for interventions aimed to reduce the burden of disability. In focus groups, older adults themselves describe purpose in life as a key component of successful aging [44]; this in conjunction with these and recent findings suggests that purpose may be an important psychological factor to consider when trying to identify older persons at risk for adverse health outcomes. Further, it may be possible to increase purpose in life via behavioral strategies that teach older persons to actively set goals and identify and engage in personally meaningful activities (e.g., via philanthropic, educational, or family-based activities). Importantly, purpose in life may be modifiable even among persons for whom participation in more effortful activities (i.e., physical activity) is restricted because of underlying health problems. Although we are not aware of interventions focused on improving purpose in life among older adults in particular, an emerging therapeutic intervention referred to as Well-Being therapy includes a focus on purpose in life and may offer some insights[45]. Further, volunteer programs like the Experience Core may help increase purpose in life among older persons[46]. If purpose can in fact be increased, then the implications could be far reaching.

This study has some notable strengths, including the assessment of purpose in life in a large group of community-dwelling older persons free of dementia at baseline and who underwent detailed annual structured clinical evaluations to document incident disability. Disability was assessed at evenly spaced intervals with three standardly used scales for up to eight years. Finally, we assessed purpose in life with a standard scale previously shown to have predictive validity for adverse health outcomes in older persons. The main limitations are the selected nature of the cohort, which may have restricted our range of scores on purpose in life and limit the generalizability of findings, and the use of self-report measures of disability. Future studies are needed to elucidate the biologic basis of the association of purpose in life with disability and to examine the association of purpose in life with additional health outcomes in older persons.

Figure 2.

Cumulative hazard of developing disability in instrumental activities of daily living for a participant with a high (dotted line) vs. low (solid line) level of purpose in life.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIA grants R01AG17917 and R01AG24480, K23AG040, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Robert C. Borwell Endowment Fund. The authors have no disclosures to report.

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging grants R01AG17917 and R01AG24480, K23AG040, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Robert C. Borwell Endowment Fund. We are indebted to the participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project and thank Traci Colvin, MPH and Tracey Nowakowski for Study Coordination, and Woojeong Bang, MS for statistical programming.

References

- 1.Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning. New York: Washington Square Press, Simon and Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(4):719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zika S, Chamberlain K. On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. Br J Psychol. 1992;83(1):133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryff CD, Singer B, Love GD. Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Phioslos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1383–1394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause N. Stressors in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S287–S297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol Inq. 1998;9(4):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, de Leon CF, Kim HJ, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Correlates of life space in a volunteer cohort of older adults. Exp Aging Res. 2007;33(1):77–93. doi: 10.1080/03610730601006420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-based older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(5):574–579. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease in old age. Archives of General Psychiatry In press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraus N. Meaning in life and mortality. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;64(4):517–27. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, Davidson RJ, Singer B. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(2):85–95. doi: 10.1159/000090892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Miller GE, Schulz R, Carver CS. Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(12):1494–1508. doi: 10.1177/0146167203256921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steptoe A, O’Donnell K, Marmot M, Wardle J. Positive affect, psychological well-being, and good sleep. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(4):409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de Leon C, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. The Rush memory and aging project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Mild cognitive impairment: risk of Alzheimer disease and rate of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2006;67(3):441–445. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228244.10416.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann G, Drachmann D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan E. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services task force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz S, Akpom C. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. Journal of Gerontology. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993 May;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Professional manual: revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NE five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessments Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Arnold SE, Wilson RS. The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2006 May;5(5):406–12. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables [with discussion] J R Stat Soc (B) 1972;74:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ormel J, Wohlfarth T. How neuroticism, long-term difficulties, and life situation change influence psychological distress: a longitudinal model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(5):744–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.5.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes de Leon CF, Gold DT, Glass TA, Kaplan L, George LK. Disability as a function of social networks and support in elderly African Americans and Whites: the Duke EPESE 1986–1992. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001 May;56(3):S179–90. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.3.s179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalle Carbonare L, Maggi S, Noale M, Giannini S, Rozzini R, Lo Cascio V, Crepaldi G ILSA Working Group. Physical disability and depressive symptomatology in an elderly population: a complex relationship. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA) Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;17(2):144–54. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e31818af817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Physical activity is associated with incident disability in community-based older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger KR, Wilson RS, Shah RC, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Personality and incident disability in older persons. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):428–33. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson RS, Buchman AS, Arnold SE, Shah RC, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Harm avoidance and disability in old age. Exp Aging Res. 2006;32(3):243–61. doi: 10.1080/03610730600699142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kempen GIJM, van Sonderen E, Omel J. The impact of psychological attributes on changes in disability among low functioning older persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54B:23–29. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorm AF, Christensen H, Henderson S, Korten AE, MacKinnon AJ, Scott R. Neuroticism and self-reported health in an elderly community sample. Pers Individ Diff. 1993;15:515–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindfors P, Lundberg U. Is low cortisol level an indicator of positive health? Stress Health. 2002;18:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singer B, Ryff CD. New horizons in health: an integrative approach. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman EM, Hayney M, Love GD, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Plasma interleukin-6 and soluble IL-6 receptors are associated with psychological well-being in aging women. Health Psychol. 2007;26(3):305–13. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman PJ, Steptoe A. Psychosocial and socioeconomic factors associated with glycated hemoglobin in nondiabetic middle-aged men and women. Health Psychol. 2003;22(4):398–405. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen HJ, Pieper CF, Harris T, Rao KM, Currie MS. The association of plasma IL-6 levels with functional disability in community-dwelling elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Med Schi. 1997;52:M201–08. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.4.m201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brach JS, Solomon C, Naydeck BL, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Enright PL, Jenny NS, Chaves PM, Newman AB Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. Incident physical disability in people with lower extremity peripheral arterial disease: the role of cardiovascular disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1037–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Frailty is associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in the elderly. Psychosom Med. 2007 Jun;69(5):483–9. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e318068de1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells JN, Bush HA, Marshall D. Purpose-in-life and breast health behavior in Hispanic and Anglo women. J Holist Nurs. 2002;20(3):232–49. doi: 10.1177/089801010202000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reichstadt J, Depp CA, Palinkas LA, Folsom DP, Jeste DV. Building blocks of successful aging: a focus group study of older adults’perceived contributors to successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(3):194–201. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318030255f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fava GA. Well-being therapy conceptual and technical issues. Psychohother Psychosom. 1999;68(4):171–179. doi: 10.1159/000012329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fried LP, Carlson MC, Glass TA, et al. Modeled cost-effectiveness of the Experience Corps Baltimore based on a pilot randomized trial. J Urban Health. 2004;81(1):64–78. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]