Abstract

A 61-year-old man treated with an autologous transplant for multiple myeloma was incidentally found to have a high level of BCR-ABL fusion gene-positive cells in his bone marrow. We describe the clinical decision-making process that led us to initiate therapy with imatinib, despite the absence of any clinical evidence of chronic myelogenous leukemia or other BCR-ABL associated hematologic malignancy.

A 60-year-old male was referred with a recent diagnosis of multiple myeloma. He presented at an outside institution with severe low back pain due to pathologic compression fractures of the thoracic spine treated with T12 vertebroplasty and T11 kyphoplasty. Workup at our institution demonstrated an IgA kappa monoclonal protein (M-spike) of 1.83 grams/dL. Bone marrow examination showed that 25% of the marrow cellularity consisted of plasma cells. Cytogenetic analysis was not performed. Blood studies showed: total calcium, 10.7 mg/dL; hemoglobin, 12.4 gm/dL; hematocrit, 33.7%; albumin, 3.6 gm/dL; and β2 microglobulin, 5.3 μg/mL. His 24-hour urine electrophoresis showed a total protein of 23.2 mg in 24 hours. The kappa free light chain was 69.7 mg/L, the lambda free light chain was 2.25 mg/L, and the kappa/lambda ratio was 31 (normal 0.26–1.65). Radiologic studies revealed diffuse osteopenia and lytic lesions in the humeri and the pelvic bones.

This patient with newly diagnosed IgA K light chain multiple myeloma (ISS II, Durie-Salmon Staging III disease) was started on thalidomide and dexamethasone, to which bortezomib was subsequently added. The bone disease was treated with zoledronate and a repeat vertebroplasty, which ameliorated the patient’s back pain. He developed a mild peripheral neuropathy, but otherwise tolerated treatment well.

After four cycles of therapy, serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation failed to detect a paraprotein, and bone marrow examination failed to identify a clonal CD138-positive plasma cell population by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry. Cytogenetic analysis was normal.

Six months following presentation the patient underwent autologous transplantation after conditioning with melphalan (200mg/m2) using stem cells obtained by mobilization with cyclophosphamide. The immediate post-transplantation course was uneventful. His only complaints were related to frequent upper respiratory and sinus infections, which responded well to levofloxacin. Monthly treatment with zoledronate was continued. Immunofixation studies performed 4, 8, and 10 months post-transplantation failed to detect a paraprotein, but did reveal low IgA levels ranging from 29 to 62 mg/dL. CBCs performed 4, 8, and 10 months post-transplantation showed stable peripheral blood counts. During this time interval, the WBC ranged from 4.1 to 6.0 x 103/μl, the hemoglobin level from 11.4 to 13.1 gm/dl, the hematocrit from 31.9% to 37.7%, and the platelet count from 126 to 139 x 103/μl. Other laboratory studies were within normal limits.

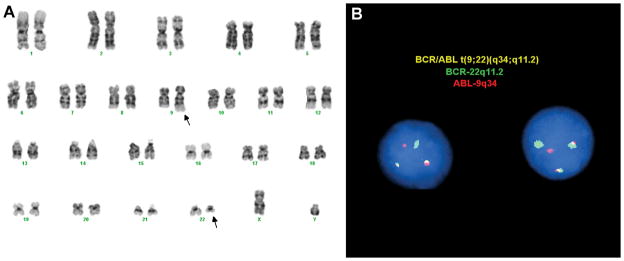

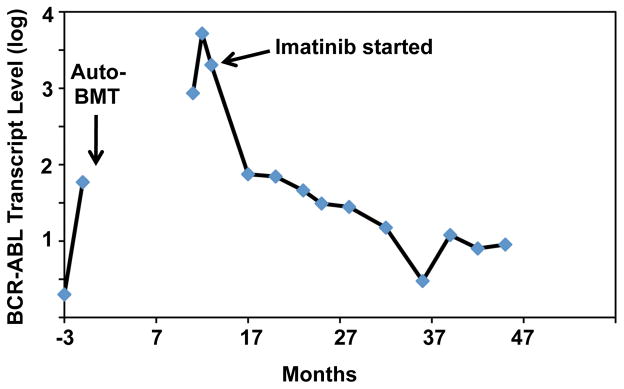

The patient returned for a routine follow-up clinic visit 12 months post-transplantation. He felt well and had no complaints. There was no palpable organomegaly or lymphadenopathy. A CBC revealed a WBC of 7.3 x 103/μl, a hemoglobin level of 13.1 gm/dL, and hematocrit of 38.1%, and a platelet count of 138 x 103/μl. A routine surveillance bone marrow biopsy and aspirate revealed a slightly hypocellular marrow with a mild relative predominance of erythroid precursors, trilineage maturation, and scattered normal-appearing plasma cells; there was no eosinophilia or basophilia (Fig. 1). Cytogenetic analysis of aspirated marrow, sent to screen for abnormalities associated with multiple myeloma, showed the presence of a balanced translocation involving chromosomes 9 and 22 (the so-called Philadelphia chromosome) in 15 of 20 metaphases (Fig. 2A). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with probes specific for BCR and ABL demonstrated the presence of a BCR-ABL fusion gene in 20 of 100 interphase nuclei scored (Fig. 2B).

Figure 1.

Bone marrow biopsy (40X, Wright Giemsa stain, 12 months after auto-transplantation for multiple myeloma). The marrow is slightly hypocellular and exhibits trilineage maturation and erythroid predominance; plasma cells are not increased in number.

Figure 2.

Detection of the t(9;22) and a BCR-ABL fusion gene. Cytogenetic and FISH analyses performed on a bone marrow aspirate obtained at the time of the biopsy shown in Figure 1 revealed the t(9;22) in metaphase chromosome spreads (A) and the presence of a BCR-ABL fusion gene in interphase nuclei (B). Cytogenetic and FISH analyses revealed the t(9;22) in 15 of 20 metaphases and the presence of a BCR-ABL fusion gene in 20 of 100 interphase cells, respectively.

Two weeks later, quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of peripheral blood revealed the presence of a chimeric BCR-ABL fusion mRNA transcript created by splicing of BCR exon 2 to ABL exon 2 (a b2/a2 fusion transcript). The level of the BCR-ABL fusion mRNA, relative to that of β-glucoronidase (GUS) mRNA, an internal housekeeping gene control, was 8.6%; by point of comparison, in this assay most patients presenting with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) have levels of 10% or greater.

Because the significance of a BCR-ABL fusion gene in the absence of any clinical or pathologic evidence of hematologic malignancy was uncertain, an initial decision was made to follow the patient closely with serial CBCs and qRT-PCR analysis of BCR-ABL transcript levels.

Four weeks later, the patient returned to the clinic feeling well, without weight loss, fever or other constitutional signs. The WBC was 5.7 x 103/μl, the hemoglobin level was 13 gm/dL, the hematocrit was 37.8%, and the platelet count was 136 x103/μl. However, the BCR-ABL B2/A2 fusion mRNA level in peripheral blood cells was increased to 52.2%, relative to the GUS internal mRNA control. DNA sequencing revealed that the ABL kinase coding domain of the fusion transcript matched the wild type sequence (not shown), and was therefore likely to encode a functional BCR-ABL kinase.

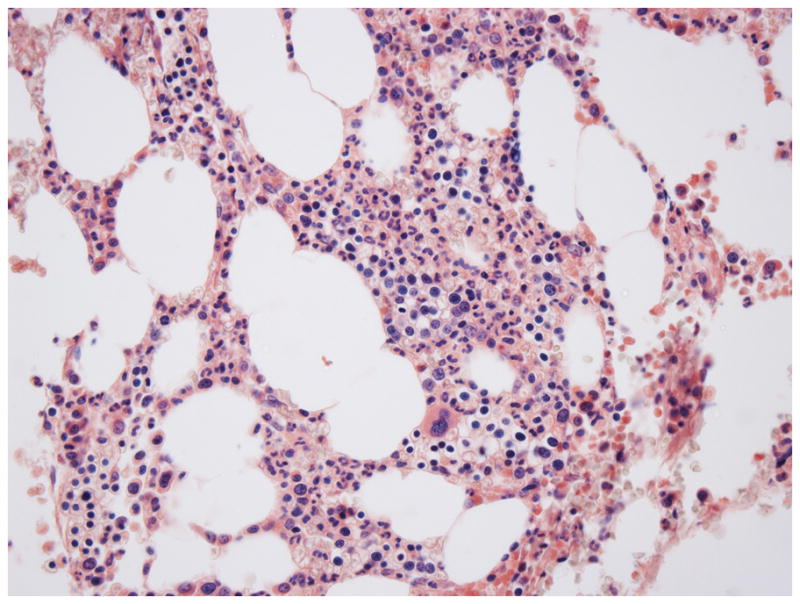

Based on the rising BCR-ABL fusion mRNA levels, the patient was started on imatinib (Gleevec), 400 mg per day, 8 weeks after initial detection of BCR-ABL-positive cells. At the time of initiation of imatinib, the WBC was 6.7 x 103/μl, the hemoglobin was 13.3 gm/dL, the hematocrit was 37.5%, and the platelet count was 121 x 103/μl. Imatinib therapy was associated with mild periorbital edema, slightly loose bowel movements, occasional cramping of the hands and feet, and mild sustained decreases in the WBC and hemoglobin level, but was otherwise well tolerated. By six months of therapy, cytogenetic analysis revealed a normal 46, XY karyotype, and by 18 months of therapy a complete molecular response was achieved, as judged by a greater than 3-log drop in the level of the BCR-ABL fusion transcript (Fig. 3). As of this writing almost 3 years after the initial detection of the t(9;22), his “CML” and multiple myeloma remain in remission on Gleevec and zoledronate.

Figure 3.

BCR-ABL fusion transcript levels. Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to detect and quantify the levels of BCR-ABL fusion transcripts, relative to an internal housekeeping control gene (GUS), at various points in the patient’s course.

Commentary

The coexistence of multiple myeloma (MM) and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) raises a number of questions related to the pathogenic interrelationship and treatment of these two diseases. Only a small number of case reports of CML and MM occurring in the same patient, either synchronously or metachronously, have been published over the last fifty years (1–8). A few authors have speculated that coexistent CML and MM might arise from a common aberrant hematopoietic stem cell with both lymphoid and myeloid potential (3, 8); however, it is now generally accepted that CML originates in a hematopoietic stem cell and that MM arises from a post-germinal center B cell, making it very unlikely that these tumors ever share a common clonal origin. A more relevant issue in this case is whether the CML was induced by the conditioning regimen used for auto-transplantation. Based on studies of the survivors of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II (9), it has long been known DNA-damaging agents such as ionizing radiation increase the incidence of CML, and in vitro work has shown that the appearance of BCR-ABL fusion genes can be induced in cells by ionizing radiation (10). It thus seemed possible that conditioning with cyclophosphamide might have caused DNA breaks that led to the appearance of the BCR-ABL-positive clone in our patient. To assess this possibility, we performed a retrospective analysis of pre-transplant marrow aspirates. RT-PCR analysis of marrow obtained 3 months prior to transplant showed a b2/a2 BCR-ABL fusion transcript of 0.02%, and a second marrow obtained two months later (1 month prior to transplant) showed a B2/A2 fusion transcript level of 0.59% (Fig. 3). The 30-fold rise in BCR-ABL transcript levels over a two-month time interval is consistent with an early preclinical phase of CML and excludes the possibility that the conditioning regimen induced the appearance of the BCR-ABL-positive clone.

An key clinical question raised by this case is whether patients with molecular evidence of a BCR-ABL fusion gene who are asymptomatic and have normal blood counts should be treated. Very sensitive RT-PCR assays have detected BCR-ABL fusion transcripts in the peripheral blood cells of roughly 30% of normal adults (11–13), the vast majority of whom never develop CML or any other hematologic malignancy. These transcripts are generally present at very low levels, leading to estimates that 1–10 out of 108 peripheral blood leukocytes harbor a BCR-ABL fusion gene in positive samples (12, 13). BCR-ABL fusion transcripts are undetectable in cord blood and are only very rarely detected in children (12), indicating that they become more prevalent with aging. Why these BCR-ABL-positive clones fail in the vast majority of cases to give rise to malignancy is uncertain; although BCR-ABL is necessary and sufficient to produce a CML-like phenotype in animal models (14), it is possible that additional rate-limiting mutations are needed for CML development in humans. Alternatively, “background” BCR-ABL-positive cells might arise from committed hematopoietic progenitors that lack self-renewal capacity and that therefore extinguish by differentiation over time, never producing disease, or might be eliminated by immune surveillance.

Our patient differed in that the BCR-ABL fusion gene was detected by FISH in 20% of marrow cells, a much higher level than is typical of asymptomatic individuals. Moreover, the increase in BCR-ABL fusion transcript levels in serial samples was also consistent with an evolving preclinical phase of CML. These objective laboratory findings and two other considerations informed our decision to start imatinib therapy. Firstly, imatinib is generally very well tolerated. Secondly, the risk of development of imatinib-resistance increases with disease duration (15), and progression to accelerated phase CML or blast crisis can occur unpredictably at any point in the disease course. Because long-term follow-up of patients with stable phase CML has shown that treatment with imatinib lessens the risk of both of these feared complications (16), we decided that starting therapy was the most prudent course to follow.

In our patient, the rapid and deep molecular response to imatinib confirmed that the BCR-ABL kinase conferred a strong selective advantage on the BCR-ABL-positive clone, suggesting that he indeed had a “pre-clinical” form of CML. However, it must be admitted that the natural history of such cases is unknown. Of note in this regard, another recent case report described an asymptomatic adult with mild leukocytosis who was incidentally discovered to have the t(9;22) in approximately 15% of peripheral blood leukocytes by FISH (17). At one year of follow-up on no treatment, the level of BCR-ABL-positivity in bone marrow cells was 52% by FISH, but the WBC was in the normal range, as were other blood counts. Hence, it remains to be determined whether a high level of BCR-ABL-positivity in hematopoietic progenitors is an inevitable harbinger of CML or other BCR-ABL-associated malignancies.

References

- 1.Boots MA, Pegrum GD. Simultaneous presentation of chronic granulocytic leukaemia and multiple myeloma. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:364–365. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derghazarian C, Whittemore NB. Multiple myeloma superimposed on chronic myelocytic leukemia. Can Med Assoc J. 1974;110:1047–1050. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klenn PJ, Hyun BH, Lee YH, Zheng WY. Multiple myeloma and chronic myelogenous leukemia--a case report with literature review. Yonsei Med J. 1993;34:293–300. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1993.34.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacSween JM, Langley GR. Light-chain disease (hypogammaglobulinemia and Bence Jones proteinuria) and sideroblastic anemia--preleukemic chronic granulocytic leukemia. Can Med Assoc J. 1972;106:995–998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nitta M, Tsuboi K, Yamashita S, Kato M, Hayami Y, Harada S, Komatsu H, Iida S, Banno S, Wakita A, Ueda R. Multiple myeloma preceding the development of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Int J Hematol. 1999;69:170–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raz I, Polliack A. Coexistence of myelomonocytic leukemia and monoclonal gammopathy or myeloma. Simultaneous presentation in three patients. Cancer. 1984;53:83–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840101)53:1<83::aid-cncr2820530115>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakai A, Kawano M, Oguma N, Kuramoto A. A case of plasma cell leukemia superimposed on Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am J Hematol. 1991;36:222–223. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830360317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka M, Kimura R, Matsutani A, Zaitsu K, Oka Y, Oizumi K. Coexistence of chronic myelogenous leukemia and multiple myeloma. Case report and review of the literature. Acta Haematol. 1998;99:221–223. doi: 10.1159/000040843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K, Takechi M, Hong J, Shigeta C, Oguma N, Kamada N, Takimoto Y, Kuramoto A, Dohy H, Kyo T. 9;22 translocation and bcr rearrangements in chonic myelocytic leukemia patients among atomic bomb survivors. J Radiat Res. 1989;30:352–358. doi: 10.1269/jrr.30.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deininger MW, Bose S, Gora-Tybor J, Yan XH, Goldman JM, Melo JV. Selective induction of leukemia-associated fusion genes by high-dose ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1998;58:421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basecke J, Griesinger F, Trumper L, Brittinger G. Leukemia- and lymphoma-associated genetic aberrations in healthy individuals. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:64–75. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biernaux C, Loos M, Sels A, Huez G, Stryckmans P. Detection of major bcr-abl gene expression at a very low level in blood cells of some healthy individuals. Blood. 1995;86:3118–3122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bose S, Deininger M, Gora-Tybor J, Goldman JM, Melo JV. The presence of typical and atypical BCR-ABL fusion genes in leukocytes of normal individuals: biologic significance and implications for the assessment of minimal residual disease. Blood. 1998;92:3362–3367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melo JV, Barnes DJ. Chronic myeloid leukaemia as a model of disease evolution in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:441–453. doi: 10.1038/nrc2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Druker BJ. Translation of the Philadelphia chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood. 2008;112:4808–4817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-077958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherbenou DW, Druker BJ. Applying the discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2067–2074. doi: 10.1172/JCI31988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayraktar S, Goodman M. Detection of BCR-ABL-positive cells in an asymptomatic patient: a case report and literature review. Case Reports in Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/939706. Article ID 939707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]