Abstract

To address issues resulting from α estrogen receptor-knockout (αERKO) residual N-terminal truncated estrogen receptor α, and to allow tissue-selective deletion of ERα, we generated loxP-flanked exon 3 mice. Initial characterization of global sox2 cre-derived exon 3-deleted Ex3αERKO mice indicated no ERα protein in uterine tissue and recapitulation of previously described female phenotypes, confirming successful ablation of ERα. Body weights of Ex3αERKO female mice were 1.4-fold higher than wild-tupe (WT) females and comparable to WT males. Microarray indicated the Ex3αERKO uterus is free of residual estrogen responses. RT-PCR showed Nr4a1 is increased 41-fold by estrogen in WT and 7.4-fold in αERKO, and not increased in Ex3αERKO. Nr4a1, Cdkn1a, and c-fos transcripts were evaluated in WT and Ex3αERKO mice following estrogen, IGF1, or EGF injections. All 3 were increased by all treatments in WT. None were increased by estrogen in Ex3αERKO. Nr4a1 increased 24.5- and 14.7-fold, Cdkn1a increased 14.2- and 12.3-fold, and c-fos increased 20.9-fold and 16.2-fold after IGF1 and EGF treatments, respectively, in the Ex3αERKO mice, confirming that growth factor regulation is independent of ERα. Our Ex3α ERα model will be useful in studies of complete or selective ablation of ERα in target tissues.—Hewitt, S. C., Kissling, G. E., Fieselman, K. E., Jayes, F. L., Gerrish, K. E., Korach, K. S. Biological and biochemical consequences of global deletion of exon 3 from the ERα gene.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, uterus, knockout

In 1993, the first estrogen receptor (ER) α-null (αERKO) mouse was generated (1) and has proven to be a worthwhile experimental model in understanding the importance of ERα in biological and physiological processes. We encountered some limitations to the model, however. First, in females the lack of ERα leads to disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonad (hpg) axis, such that the endocrine environment is altered, making direct comparisons to wild-type (WT) counterparts difficult. In addition, the ERα is absent in all tissues and cell types, and some tissues do not develop completely, thus making it difficult to compare cell-specific effects. Finally, although the initial αERKO was generated via insertional disruption by homologous recombination to produce a noncoding transcript, an unanticipated splicing event led to production of a truncated ERα protein (E1-ERα), which lacked the N terminus of the ERα, including the activation function 1 (AF1) region and is present at ∼10% of the WT ERα protein level in uterine tissue (2). The presence of E1-ERα protein results in some residual responses in the uterus. Although no estrogen (E)-dependent increase in weight or epithelial cell proliferation occurs, some early ERα target genes, such as c-fos, have E-dependent increases, although less robust increases than WT (3). Insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF1) or epidermal growth factor (EGF) treatment of ovariectomized WT mice results in uterine proliferation, but no response occurred in the αERKO. However, a microarray study indicated many gene responses were retained in the growth factor stimulated αERKO (4). One potential mechanism accounting for the growth factor-dependent gene responses of the αERKO is the presence of the residual truncated ERα, E1-ERα. To address some of these issues, an ERα model, similar in design to one previously generated (5), in which the exon 3 sequences (DNA binding) are flanked by loxP sites was developed. This model can be crossed with a global cre mouse to generate an ERα-null model, the exon 3-deleted Ex3αERKO, which lacks the residual splice variant ERα protein and in which previously identified residual responses could be assessed. In addition, the model is amenable to generation of tissue selective ablation of ERα by intercrossing with various cre-expressing mouse lines on tissue-selective promoters, allowing more direct comparison of effects mediated by loss of ERα.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Ex3αERKO mice

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Humane Use and Care of Animals and an approved National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences animal protocol. Esr1 with exon 3 flanked by loxP sites was generated by Xenogen (Caliper Life Sciences, Cranbury, NJ, USA) using a strategy similar to that described by Dupont et al. (5). The construct was electroporated into C57BL/6N Tac ES cells, which were then injected into B6 albino blastocysts. Resulting chimeras were then bred with B6 albino females and black F1 pups were genotyped for the presence of the floxed allele. The Esr1 was deleted by crossing mice carrying floxed exon 3 Esr1 with a global Sox2-cre (Tg(Sox2-cre)1Amc/J; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor ME, USA), which expresses Cre activity in the epiblast line allowing germ-line deletion of targeted genes (6). DNA was isolated from tail biopsies using Direct PCR reagent (Viagen Biotech, Los Angeles, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol and evaluated by PCR using the P1 P3 primers described by Dupont et al. (5) for ablation of Esr1.

Treatment of mice

For analysis of ERα protein levels, uteruses were collected from intact females and a portion fixed in formalin. For response studies, mice were ovariectomized and after 10 to 14 d were injected with 100 μl saline, or 250 ng estradiol (E2, Steraloids) in 100 μl saline, and three uteruses per treatment group were collected after 2 or 24 h. For growth factor treatments, 50-μg-long R3-IGF1 (Cell Sciences, Canton MA, USA), an IGF1 analog with decreased IGFBP interaction, in 100 μl sesame oil (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), or 200 μg mouse EGF (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in 200 μl oil were injected ip and three uteruses per group were collected after 2 h, or the growth factors were delivered by osmotic pump (Durect, Cupertino, CA, USA) for 24 h (EGF 2.5 mg/ml, longR3IGF1 0.5 mg/ml) as described previously (4).

Hormone assays

Blood was collected by mandibular bleeds and serum was prepared. LH levels were measured in 20 μl of serum (ng/ml) using a sensitive low-volume dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluoro-immunoassay (DELFIA) as described by Bielmeier et al. (7) with a detection range of 0.6–2,000 pg/tube. A National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) mouse LH reference preparation was used as a standard (mLH-RP AFP5306A; obtained from the National Hormone and Peptide Program, Torrance, CA, USA). The lowest standard used in our assays was 0.03 ng/ml, and samples below 0.03 were assigned a value of 0.02 ng/ml before data were analyzed. Testosterone levels were assayed from 50 μl of serum using the DSL-active coated tube RIA (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX, USA).

RT-PCR

Uterine RNA was isolated and 2 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed as previously described (3). To evaluate for ERα transcript, primers (438F and 1007 rev) spanning exons 2 to 5 were used and amplified with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) in 1× PCR buffer I (Invitrogen) with 35 cycles of 95 C for 30 s, 56 C for 30 s and 72 C for 2 min. In addition, primers spanning exons 4 to 8 (923 forward: AATGTTACGAAGTGGGCATGA and 1775 reverse: TGTTGTAGAGATGCTCCATGCC) were used and amplified in 1× RedTaq mix (Sigma) with 30 cycles of 95 C for 30 s, 55 C for 30 s and 72 C for 1 min. Amplimers were separated on 3% 3:1 NuSeive:Agarose (Lonza, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in 1× TBE (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA).

For real-time PCR, cDNA was analyzed as described previously using 1× PowerSybr mix (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) (3).

Western blot analysis

Uterine homogenates were prepared as described previously (3), separated on 10% NuPage gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot apparatus (Invitrogen). ERα was detected as described previously (8).

Immunohistochemistry

Uterine cross sections were mounted on charged slides (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA), and ERα, Ki67, and BrdU were detected as described previously (8, 9).

Mammary whole mounts

Inguinal mammary glands 4/5 were dissected and fixed and stained as described previously (10).

Growth curves

WT or Ex3αERKO male and female mice were weighed weekly beginning at the age of 50 d. Data were plotted, and then cubic polynomial growth curves were fitted using PROC MIXED in SAS (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) with autoregressive covariance matrix (AR; ref. 1) within animal. Males and females were fitted separately, allowing for different intercepts, linear terms, quadratic terms, and cubic terms for WT and Ex3αERKO through the use of interaction terms of genotype with age, age^2, and age^3. A similar approach was taken to compare growth curves of males and females, separately for WT and Ex3αERKO mice.

Piximus

WT or Ex3αERKO adult females (9–16 wk) were lightly anesthetized using isoflurane and imaged using a Piximus X-ray Densitometer (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Fat content and bone mineral density were obtained from analysis outputs.

Microarray

RNA was isolated as for RT-PCR, but was further purified using Qiagen RNeasy cleanup protocols (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Gene expression analysis was conducted using Agilent Whole Mouse Genome 4x44 multiplex format oligo arrays (14868; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) following the Agilent 1-color microarray-based gene expression analysis protocol. Starting with 500 ng of total RNA, Cy3-labeled cRNA was produced according to manufacturer's protocol. For each sample, 1.65 μg of Cy3-labeled cRNAs were fragmented and hybridized for 17 h in a rotating hybridization oven. Slides were washed and then scanned with an Agilent scanner. Data were obtained using the Agilent Feature Extraction software (ver. 9.5), using the 1-color defaults for all parameters. The Agilent Feature Extraction Software performed error modeling, adjusting for additive and multiplicative noise. Processed microarray data were analyzed with a variety of unsupervised and supervised techniques in Rosetta Resolver (ver. 7.2; Rosetta Biosoftware, Kirkland, WA, USA; http://www.rosettabio.com). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all samples and all probe sets to characterize the variability present in the data. To identify differentially expressed probes, ANOVA was used to determine whether there was a statistical difference between the means of groups. Specifically, an error-weighted ANOVA using multiple-test correction was performed using Rosetta Resolver. Bonferroni multiple test correction was used to reduce the number of false positives and the P value used to generate the ANOVA results was P < 0.01. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Entrez gene IDs with the agglomerative clustering algorithm and the cosine correlation similarity metric. In addition, 2-fold-change cutoff, a P value threshold (P<0.001), and a signal intensity value > 100 in ≥1 treatment were used to further filter the data by generation of biosets for each ratio in the clusters. After filtering, 9200 Entrez genes remained. The data set is available through GEO (accession GSE 23072).

RESULTS

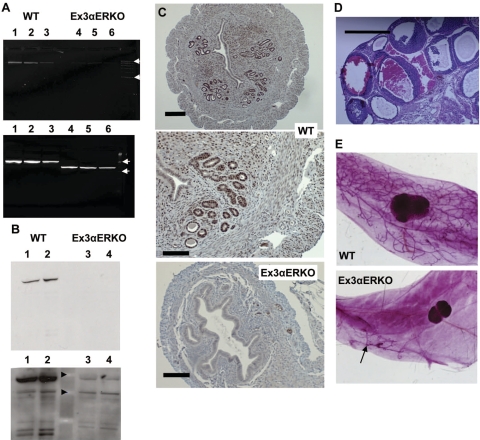

To confirm the successful deletion of ERα, uterine RNA was analyzed by RT-PCR for the presence and relative amount of the expected transcript. As shown in Fig. 1A, primers that span exons 4–8, downstream of the deleted exon, detect a similarly sized band in WT and Ex3αERKO samples, but the band is less intense in the Ex3αERKO lanes. Primers that span the deletion site (exons 2–5) detect a smaller band in the Ex3αERKO uterine cDNA that is not seen in the WT, indicating successful deletion of exon 3. A low-intensity band at the WT size was observed in the Ex3αERKO samples. To determine whether the ERα protein was successfully deleted, total uterine protein was isolated and analyzed by Western blot with an antibody to the N terminus of the ERα. As shown in Fig. 1B, no ERα protein is detectable using an exposure that readily detects ERα in a WT sample, although a faint band is observed after overexposure. To visualize any uterine cells that might be producing ERα proteins, uterine sections were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1C). ERα is readily detected in the nucleus of most uterine cells in the WT but is not detected in the Ex3αERKO.

Figure 1.

A) RT-PCR of ERα transcripts. Top panel: cDNA made from WT (lanes 1–3) or Ex3αERKO (lanes 4–6) uterine RNA was amplified using primers that spanned exon 4 to exon 8, yielding an 850-bp amplimer. Arrows show 1000- and 500-bp markers. Bottom panel: PCR from primers spanning eons 2 to 5 yielded a 560-bp amplimer in WT (lanes 1–3), and a smaller amplimer in Ex3αERKO (lanes 4–6). Arrows show 600- and 300-bp markers. B) ERα Western blot of 10 μg total uterine protein from WT (lanes 1 and 2) or Ex3αERKO (lanes 3 and 4) uteruses from a 1-min exposure (top panel) or a 10-min overexposure (bottom panel). ERα antibody sc 542 recognizes N-terminal epitope. Arrowheads show 64- and 51-kDa markers. C) ERα immunodetection in sections of WT (top and middle) or Ex3αERKO (bottom) intact uteruses. D) Ex3αERKO ovary showing hemorrhagic cystic pathology. E) Mammary gland whole mounts showing fully developed epithelial structure in adult (>10 wk) WT and rudimentary ductal structure in adult (>10 wk) Ex3αERKO (arrow) ovariectomized mice. Scale bars = 0.2 μM (C, top panel); 0.1 μM (C, middle and bottom panels); 0.5 μM (D).

Several biological phenotypes that were observed in the original ERα-null models were compared in the Ex3αERKO tissues. First, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis leads to inappropriate ovarian stimulation, and one hallmark phenotype of the αERKO is the abnormal endocrine environment, including elevated serum testosterone, estradiol, and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels in females (11). Serum testosterone in Ex3αERKO females was elevated more than 20-fold (2.81±0.35 vs. 0.13±0.04 ng/ml in WT females). Serum LH values were elevated 6.5-fold in Ex3αERKO females (0.68±0.19 and 4.6±0.32 ng/ml in WT and Ex3αERKO, respectively). These elevated values are consistent with the need for ERα to mediate negative feedback and with the endocrine and hemorrhagic cystic ovarian phenotype (Fig. 1D) seen previously (12, 13).

Mammary gland development in the original αERKO was impaired, with only a rudimentary ductal structure present in adult females (11). Examination of mammary gland whole mounts indicates the presence of this phenotype in the Ex3αERKO as well (Fig. 1D) demonstrating the formation of the ductal rudiment is independent of ERα, but that pubertal growth of the structure depends on ERα.

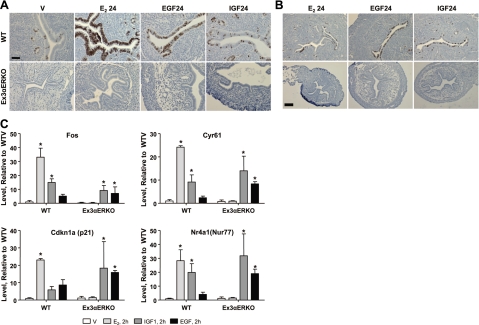

IGF1 or EGF can mimic E2 by increasing uterine proliferation. This response is ERα dependent, as it was lost in the original αERKO, although numerous genes remained responsive (14, 15). The response was examined in the Ex3αERKO (Fig. 2A, B). E2, EGF, and IGF1 all increase Ki67 (Fig. 2A), reflecting proliferative response, as well as BrdU incorporation (Fig. 2B), indicative of DNA synthesis and S phase, of WT epithelial cells, while none are effective in Ex3αERKO. Although there was no proliferation, our previous study indicated numerous transcriptional responses to growth factors in the αERKO (4). To ensure this growth factor response is independent of the residual E1 ERα, several transcripts that were growth factor regulated in αERKO were assayed in the Ex3αERKO (Fig. 2C). EGF and IGF1 increased levels of c-fos, Cyr61, Cdkn1a, and Nr4a1 transcripts in WT, as well as the Ex3αERKO, while E2 increased the transcripts only in WT, indicating the growth factor responses are ERα independent, and as was seen with the original αERKO study, despite no growth response, the growth factor sensitive transcript responses still occur.

Figure 2.

A) Ki67 immunodetection in sections of WT (top panels) or Ex3αERKO (bottom panels) uteruses that were ovariectomized and treated for 24 h with saline (V), E2, EGF, or IGF1. B) BrdU incorporation in sections of WT (top panels) or Ex3αERKO (bottom panels) uteruses that were ovariectomized and treated for 24 h with E2, EGF, or IGF1 and for 2 h with BrdU. C) RT-PCR of ERα-independent growth factor-responsive transcripts in WT or Ex3αERKO uterine samples injected for 2 h with saline vehicle (V), E2, EGF, or IGF1 at doses described in Materials and Methods. Data were tested by 2-way ANOVA t test with a Bonferroni correction to determine significance relative to the V level. *P < 0.05. Scale bars = 0.04 μM (A); 0.10 μM (B).

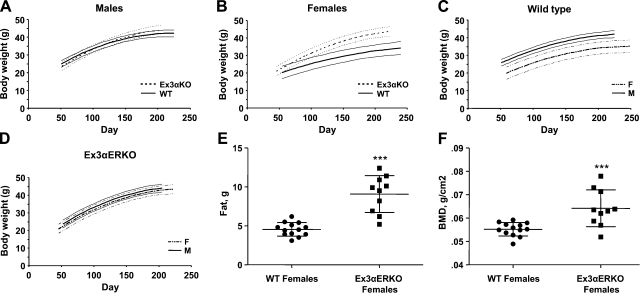

Estrogen is important in regulating body fat as evidenced by studies indicating ovariectomy leads to increased body weight in rodents (16, 17) and the obesity of original αERKO females (18), as well as other ERα-null models (12). The body weights of male and female Ex3αERKO mice were measured weekly from 50 d until at least 200 d. While growth curves were initially cubic polynomials in age, none of the cubic terms were significant (all P>0.16), so all subsequent modeling was based on quadratic growth curves. The growth curves for male WT and Ex3αERKOs substantially overlap each other and do not differ significantly within the range of days covered by the study (Fig. 3A; likelihood ratio test, P=0.21). In contrast, within the range of days covered by the study, Ex3αERKO and WT females have distinct, significantly different growth curves (Fig. 3B; likelihood ratio test, P=0.001). The linear trajectory was significantly steeper for Ex3αERKO females than for WT females (P<0.0001), reflecting the more rapid weight gain and greater body weights in Ex3αERKO females compared to WT females (Fig. 3B). The rate of growth slowed down faster in Ex3αERKO females than in WT females, as indicated by the smaller quadratic coefficient for Ex3aERKO females. Interestingly, the Ex3αERKO female growth curve was similar to that of Ex3αERKO males, unlike the WT, which shows sexual dimorphism (Fig. 3C, D). The quadratic growth model for Ex3αERKO did not differ significantly between males and females (P=0.31). The growth models for WT males and females had significantly different linear and quadratic components (P<0.005).

Figure 3.

Growth curves. Body weights were recorded weekly and compared on plots of WT vs. Ex3αERO males (A) or females (B). Males and females were also compared in plots (C, WT; D, Ex3αERKO). Ex3αERKO females resemble males in their growth pattern. Total body fat content (E) and bone mineral density (BMD; F) of adult (84–112 d old) WT and Ex3αERKO females was evaluated by Piximus imaging and compared. A) WT (n=11) and Ex3αERKO (n=14) males. B) WT (n=9) and Ex3αERKO (n=14) females. C) WT males and females. D) Ex3αERKO males and females. E, F) Fat content (E) and BMD (F) of WT (n=13) and Ex3αERKO (n=10) females.

As the body weights of Ex3αERKO females were significantly higher, Piximus Imaging was used to determine amount of total body fat and bone density on a group of adult (12–16 wk old) females. Ex3αERKO females have significantly more fat than WT (Fig. 3E), which contributes to the increased body weights. The bone mineral density of the Ex3αERKO females has a wide range of values; however, the mean is significantly higher than in WT females (Fig. 3E).

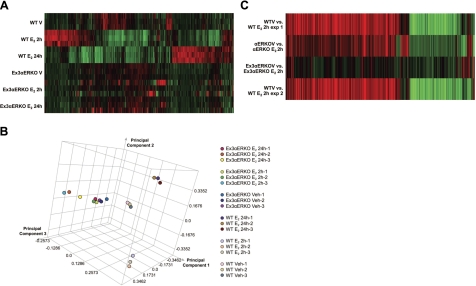

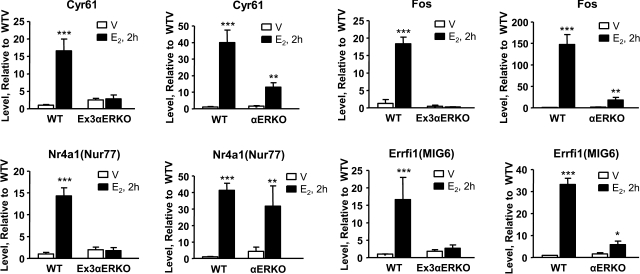

Our previous studies with the αERKO examined E2-mediated uterine transcriptional responses by microarray analysis of ovariectomized mice injected with saline or E2 for 2 or 24 h (3). Most transcriptional responses were absent in the αERKO; however, some targets retained activity. These were most likely mediated by the presence of the residual ERα splice variant. To evaluate the transcriptome in the Ex3αERKO, and also to evaluate the relative basal transcriptome, similar samples were examined using a 44k 1-color array system; 9200 transcripts were significantly changed (P<0.001) in WT and reproduced the previous observation of distinct early (2 h) and late (24 h) responses (Fig. 4A). Deletion of ERα in the Ex3αERKO abolished most responses (Fig. 4A), similar to the results with the previous αERKO model (3). Principal component analysis of the samples separated the samples into 3 groups (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that the Ex3αERKO samples, regardless of treatment, are more similar to the WT V samples than the WT 2- or 24-h-treated E2 samples. We previously reported residual E2 regulation of some uterine transcripts in the αERKO (2). To compare and further determine whether these residual transcripts are also present in the Ex3αERKO samples, we compared ratio experiments from previously obtained data of the αERKO that were from 2-color arrays (ref. 9; GEO accession GSE 18168), and the current 1-color data. We clustered 573 transcripts that were regulated by E2 after 2 h in αERKO (P<0.001) with WT and Ex3αERKO data (Fig. 4C) from our current data. While these transcripts are similarly regulated in WT and αERKO, they are not present in the E2-treated Ex3αERKO. Transcripts that are increased by E2 in the αERKO (Cyr61, Fos, Nr4a1, and Errfi1) were tested in the Ex3αERKO by RT-PCR of independent samples. None were increased in the Ex3αERKO, indicating that all these responses were eliminated by completely removing ERα (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Microarray analysis of uterine samples. A) Two-dimensional (2-D) cluster comparing individual uterine samples from WT or Ex3αERKO animals treated with saline vehicle (V) or for 2 or 24 h with E2. The 2-D cluster was generated using Rosetta Resolver software. It compares Z scores derived from the intensity values of individual uterine samples from WT or Ex3αERKO animals treated with saline vehicle or for 2 or 24 h with E2. B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of gene expression from triplicate WT or Ex3αERKO uterine RNA after treatments with saline vehicle, or E2 for 2 or 24 h. PCA separated the samples into 3 groups: WT V and Ex3αERKO, WT E2 2 h, and WT E2 24 h. The 2-D cluster (A) and PCA (B) were generated using Rosetta Resolver software. They compare Z scores derived from the intensity values of individual uterine samples from WT or Ex3αERKO animals. C) Two-D cluster comparing E2 2 h to vehicle treatments in ratio experiments. A total of 573 transcripts were selected from a previous data set (9) because they exhibited estrogen regulation in αERKO uteruses. These 573 transcripts were then evaluated in the WT and Ex3αERKO dataset from panel A. WT V vs. WT E2 2 h exp 1and αERKO V vs. αERKO E2 2 h show ratios of the transcript intensity of estrogen-treated to vehicle in the previous 2-color array experiment. WT V vs. WT E2 2 h exp 2 and Ex3αERKO V vs. Ex3αERKO E2 2 h show built ratios from the dataset in panel A. Red and green color indicate increased and decreased signal, respectively, as a result of estrogen; intensity signifies the fold regulation.

Figure 5.

RT PCR of residual ERα E1-mediated responses. RT PCR was used to compare responses of several transcripts that have residual response to E2 in the older αERKO model uterus. For each group, n = 3 animals. Cysteine-rich protein 61 (Cyr61), FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene (c-Fos), nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 1 (Nr4a1or Nur77), and ERBB receptor feedback inhibitor 1 (Errfi1 or Mig6) lack any response in Ex3αERKO (left panels) but show residual response in the αERKO (right panels). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. saline vehicle treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to determine whether a different strategy, similar to that previously reported by Dupont et al. (5) and by Chen et al. (12) for generating an ERα-null mouse, would address issues raised by the remaining truncated E1-ERα found most notably in uterine tissue of the originally described αERKO mouse (1, 2). Most important, this approach succeeded in removing residual responses to E, which will improve future analyses that might be confounded by concerns over such responses. This was previously illustrated by studies that utilized the αERKO to address the relative roles of ERα or ERβ in a cardiovascular injury model. Unfortunately, the presence of the residual E1-ERα made it appear that E2 rescue was not mediated by ERα (19); however, use of the fully ablated ERα-null mouse revealed that the protection was mediated by ERα (20). Similarly, in this study, we were able to demonstrate elimination of both tissue responses and residual uterine transcriptional responses to E2. We did note a very faint band in our RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 1A) and on Western blot overexposure (Fig. 1B); however, the complete ablation of E response indicates that these represent nonspecific background or that residual ERα is present at levels too low to mediate response.

Of particular concern were observations such as the robust uterine transcriptional response of the αERKO uterus to EGF or IGF1 (4), which was unexpected considering the demonstration of the requirement for ERα to mediate the uterine growth response to growth factors. Examining some of these transcriptional events in the complete ERα-null model utilized in this study indicated that the growth factor-responsive transcripts are ERα independent, thus excluding residual ERα as mediating the observed responses and supporting a mechanism by which these transcripts are more directly regulated by RTK signals and additionally still demonstrating the requirement for ERα to mediate uterine growth response to E2 or growth factors. Interestingly, several of the transcripts appeared to show an enhanced response to IGF1 in Ex3αERKO in comparison, which suggests a repressive effect of the presence of ERα.

Obesity of ERα-null mice was noted previously (12, 18). In this study, we further characterized this by comparing growth curves of male and female Ex3αERKO to WTs. Increased obesity is observed in the Ex3αERKO females, and it was interesting that unlike WT, there is not a difference in growth between Ex3αERKO males and females. This pattern of growth might be due to the elevated serum testosterone observed in females that results in male-like growth patterns. Consistent with the increased body weight in Ex3αERKO females, they also displayed increased body fat. In contrast, although E is known to be essential to maintain bone density, the Ex3αERKO females have increased bone mineral density. This was previously reported (21) and may reflect the effect of increased serum testosterone, as testosterone is known to preserve bone mass in males (22). In addition, the increased body weight might also affect the bone by increasing the mechanical strain, which is known to improve bone density even in the absence of E (23). The male Ex3αERKO growth curves did not indicate an increased body weight in comparison to WT or in the amount of fat (unpublished results) in male Ex3αERKO mice. Previous studies have reported that αERKO males have decreased skeletal growth together with increased fat, resulting in no difference in body weight (24, 25).

In summary, by generating this line of Ex3αERKO mice, we created a complete ERa-null model, which enables us to address issues that were previously potentially confounded by the remaining ERα activity in the αERKO model. In addition, this mouse line demonstrates the functionality of our loxERα construct, which will be used in future studies to generate tissue-specific ERα ablation.

The authors thank David Monroy for breeding expertise and for collecting animal weights; the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Microarray Core for microarray studies and analysis; the NIEHS Histology Core for tissue sample preparation; Dr. Manas K. Ray and Mr. Greg Scott (NIEHS Knockout Mice Core) for generating the floxed Ex3 ERα mice; Comparative Medicine Branch surgeons James Clark, Page Myers, and David Goulding for ovariectomies and implanting osmotic pumps; and Karina Rodriguez for the hormone assays. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences project number Z01ES 70065.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lubahn D. B., Moyer J. S., Golding T. S., Couse J. F., Korach K. S., Smithies O. (1993) Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 11162–11166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couse J. F., Curtis S. W., Washburn T. F., Lindzey J., Golding T. S., Lubahn D. B., Smithies O., Korach K. S. (1995) Analysis of transcription and estrogen insensitivity in the female mouse after targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor gene. Molec. Endocrinol. 9, 1441–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt S. C., Deroo B. J., Hansen K., Collins J., Grissom S., Afshari C. A., Korach K. S. (2003) Estrogen receptor-dependent genomic responses in the uterus mirror the biphasic physiological response to estrogen. Molec. Endocrinol. 17, 2070–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitt S. C., Collins J., Grissom S., Deroo B., Korach K. S. (2005) Global uterine genomics in vivo: microarray evaluation of the estrogen receptor alpha-growth factor cross-talk mechanism. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 657–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupont S., Krust A., Gansmuller A., Dierich A., Chambon P., Mark M. (2000) Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development 127, 4277–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashi S., Lewis P., Pevny L., McMahon A. P. (2002) Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Mech. Dev. 119(Suppl. 1), S97–S101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bielmeier S. R., Best D. S., Narotsky M. G. (2004) Serum hormone characterization and exogeneous hormone rescue of bromodichloromethane-induced pregnancy loss in the F344 rat. Toxicol. Sci. 77, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitt S. C., Collins J., Grissom S., Hamilton K., Korach K. S. (2006) Estren behaves as a weak estrogen rather than a nongenomic selective activator in the mouse uterus. Endocrinology 147, 2203–2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt S. C., O'Brien J. E., Jameson J. L., Kissling G. E., Korach K. S. (2009) Selective disruption of ER alpha DNA-binding activity alters uterine responsiveness to estradiol. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 2111–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt S. C., Bocchinfuso W. P., Zhai J., Harrell C., Koonce L., Clark J., Myers P., Korach K. S. (2002) Lack of ductal development in the absence of functional estrogen receptor alpha delays mammary tumor formation induced by transgenic expression of ErbB2/neu. Cancer Res. 62, 2798–2805 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couse J. F., Korach K. S. (1999) Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr. Rev. 20, 358–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M., Wolfe A., Wang X., Chang C., Yeh S., Radovick S. (2009) Generation and characterization of a complete null estrogen receptor alpha mouse using Cre/LoxP technology. Mol. Cell Biochem. 321, 145–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Couse J. (1999) Reproductive phenotypes in estrogen receptor knockout mice: Contrasting roles for estrogen receptor-alpha and estrogen receptor-beta. Biol. Reprod. 60, 88–88 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klotz D. M., Hewitt S. C., Ciana P., Raviscioni M., Lindzey J. K., Foley J., Maggi A., DiAugustine R. P., Korach K. S. (2002) Requirement of estrogen receptor-alpha in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-induced uterine responses and in vivo evidence for IGF-1/estrogen receptor cross-talk. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8531–8537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis S. W., Washburn T., Sewall C., DiAugustine R., Lindzey J., Couse J. F., Korach K. S. (1996) Physiological coupling of growth factor and steroid receptor signaling pathways: estrogen receptor knockout mice lack estrogen-like response to epidermal growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 12626–12630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leshner A. I., Collier G. (1973) Effects of gonadectomy on sex-differences in dietary self-selection patterns and carcass compositions of rats. Physiol. Behav. 11, 671–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ornoy A., Giron S., Aner R., Goldstein M., Boyan B. D., Schwartz Z. (1994) Gender-dependent effects of testosterone and 17-β-estradiol on bone-growth and modeling in young mice. Bone Miner. 24, 43–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heine P. A., Taylor J. A., Iwamoto G. A., Lubahn D. B., Cooke P. S. (2000) Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 12729–12734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iafrati M. D., Karas R. H., Aronovitz M., Kim S., Sullivan T. R., Jr., Lubahn D. B., O'Donnell T. F., Jr., Korach K. S., Mendelsohn M. E. (1997) Estrogen inhibits the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor alpha-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 3, 545–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pare G., Krust A., Karas R. H., Dupont S., Aronovitz M., Chambon P., Mendelsohn M. E. (2002) Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates the protective effects of estrogen against vascular injury. Circ. Res. 90, 1087–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg M. K., Alatalo S. L., Halleen J. M., Mohan S., Gustafsson J. A., Ohlsson C. (2001) Estrogen receptor specificity in the regulation of the skeleton in female mice. J. Endocrinol. 171, 229–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanderschueren D., Vandenput L., Boonen S., Lindberg M. K., Bouillon R., Ohlsson C. (2004) Androgens and bone. Endocr. Rev. 25, 389–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tromp A. M., Bravenboer N., Tanck E., Oostlander A., Holzmann P. J., Kostense P. J., Roos J. C., Burger E. H., Huiskes R., Lips P. (2006) Additional weight bearing during exercise and estrogen in the rat: The effect on bone mass, turnover, and structure. Calcif. Tissue Int. 79, 404–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidal O., Lindberg M. K., Hollberg K., Baylink D. J., Andersson G., Lubahn D. B., Mohan S., Gustafsson J. A., Ohlsson C. (2000) Estrogen receptor specificity in the regulation of skeletal growth and maturation in male mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 5474–5479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohlsson C., Hellberg N., Parini P., Vidal O., Bohlooly M., Rudling M., Lindberg M. K., Warner M., Angelin B., Gustafsson J. A. (2000) Obesity and disturbed lipoprotein profile in estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient male mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]