Abstract

Aging of the human retina is characterized by progressive pathology, which can lead to vision loss. This progression is believed to involve reactive metabolic intermediates reacting with constituents of Bruch's membrane, significantly altering its physiochemical nature and function. We aimed to replace a myriad of techniques following these changes with one, Raman spectroscopy. We used multiplexed Raman spectroscopy to analyze the age-related changes in 7 proteins, 3 lipids, and 8 advanced glycation/lipoxidation endproducts (AGEs/ALEs) in 63 postmortem human donors. We provided an important database for Raman spectra from a broad range of AGEs and ALEs, each with a characteristic fingerprint. Many of these adducts were shown for the first time in human Bruch's membrane and are significantly associated with aging. The study also introduced the previously unreported up-regulation of heme during aging of Bruch's membrane, which is associated with AGE/ALE formation. Selection of donors ranged from ages 32 to 92 yr. We demonstrated that Raman spectroscopy can identify and quantify age-related changes in a single nondestructive measurement, with potential to measure age-related changes in vivo. We present the first directly recorded evidence of the key role of heme in AGE/ALE formation.—Beattie, J. R., Pawlak, A. M., Boulton, M. E., Zhang, J., Monnier, V. M., McGarvey, J. J., Stitt, A. W. Multiplex analysis of age-related protein and lipid modifications in human Bruch's membrane.

Keywords: advanced glycation endproducts, advanced lipoxidation endproducts, hemoglobin, Raman spectroscopy, aging

Virtually all tissues of the human eye are affected by the aging process, and this is particularly exemplified by senile cataract formation and age-related retinopathy. Together, these conditions constitute major causes of visual impairment worldwide (1, 2). Retinal dysfunction during the aging process is best appreciated at the level of the photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)-Bruch's membrane complex. This pathology is common in individuals aged >60 yr and is manifest by lipofuscin accumulation within the RPE, thickening, and protein changes within Bruch's membrane. A significant proportion of patients might progress to the late-stage manifestations of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). From a histological perspective, AMD is characterized by photoreceptor cell loss, dysfunction and death of RPE, and appearance of sub-RPE deposits such as drusen and basal laminar deposits (BLDs). Both the dry and wet forms of AMD (3) result in severe irreversible loss of central vision, and the prevalence of this disease is likely to rise further as a consequence of increasing longevity (4).

Bruch's membrane integrity is essential to normal function of the retina by stabilizing the RPE and underlying choriocapillaris and regulating diffusion between these tissues. This complex extracellular matrix thickens during aging, and profound remodeling of its constituent proteins and deposition of neutral lipids results in a net reduction in hydraulic conductivity (and hence increase in hydraulic resistivity) and charge selectivity (5–7). Such alterations have implications for the RPE, which relies on Bruch's membrane for prosurvival cues and to allow effective removal of subcellular deposits. During aging, RPE density decreases, and the surviving RPE shows decreased melanin content and altered photoreceptor outer segment degradative capacity, which is critical for age-related pathology (8, 9).

Lipids are believed to play a major role in the pathology of AMD, with unesterified cholesterol (UC) found in the retina, Bruch's membrane, and choroid, whereas esterified cholesterol (EC) is found mainly in Bruch's membrane (10, 11) and accumulates with age. In addition to the depression of hydraulic conductivity directly associated with lipid deposition, it is believed that a toxic metabolite of cholesterol (7-ketocholesterol) could have a pathogenic role in AMD (12, 13).

Bruch's membrane exists within a highly oxygenated and glucose-rich microenvironment that is also very proximal to the photoreceptors that are enriched with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). While DHA itself is not found in significant quantities in the Bruch's membrane (14), DHA is susceptible to lipid peroxidation (15), which can yield reactive aldehydes such as acrolein (ACR), 4-hydroxyhexenal (HHE), or malondialdehyde (MDA), and these can, in turn, react with proteins to form stable advanced lipoxidation endproducts (ALEs) (16), such as carboxyethylpyrrole (CEP) (17, 18). Likewise, advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) are known to accumulate in and around Bruch's membrane from postmortem eyes, were they can appear as AGE-crosslinks within both the basal lamina and drusen deposits, especially in eyes with prediagnosed AMD (19–23). Such descriptive and other experimental studies have implicated AGEs and ALEs as important pathogenic agents in age-related retinal disease (24).

Quantifying AGEs/ALEs usually requires a battery of invasive extractions and immunological and/or analytical analyses. By contrast, Raman spectroscopy is an information-dense technique that simultaneously yields considerable chemical and structural information in a single measurement. Relative concentrations of molecular constituents in a sample can be compared directly without concerns about sampling equivalence or extraction efficiencies that might arise by using some invasive approaches. The Raman approach is ideally suited for investigating biological tissue and, in the eye, it has been used to analyze carotenoid content of the macula (25), assess the histochemistry of retina (DHA, monounsaturated fats, 4 proteins, DNA, heme, cytochrome c, and kynurenine) (26, 27), detect ocular drugs (28), and assess lens structure (29, 30). We have demonstrated previously the AGEs carboxymethyl-lysine (CML) and pentosidine in aging ocular tissues using Raman spectroscopy (31–33), but the aim of the present investigation has been to extend the scope of Raman scattering significantly as a probe of age-related changes in Bruch's membrane. This approach provides novel information on the range of AGE/ALE adducts and other associated biochemical groups occurring within this matrix during aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples

Human globes (whole except for corneal buttons) from donors of various ages and both genders were obtained in saline solution from Bristol Eye Bank [Bristol, UK; n=119; 56 of these were used previously to create the published model (31), 63 to generate additional data]. Full ethical approval was obtained from the UK National Health Service Office for Research Ethics Committee, Northern Ireland, and all methods used in the research were performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human tissue. The samples were drained of saline and stored at −80°C until dissection. Bruch's membrane, incorporating attached choroid, was dissected from the sclera, and the RPE was brushed off as described previously (34); the membrane was then flat-mounted on an extrawhite glass slide (Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany) with the innermost face oriented upwards, air-dried, and stored at −20°C until ready for measurement (within 1 mo of dissection). Bruch's membranes from donors of different ages were divided into decades [<50 (30–48, n=12), 50s (49–58, n=12), 60s (60–69, n=31), 70s (70–79, n=24), 80s (80–89, n=15) and >90 (90–92, n=9)]. Age records were not traceable with 11 samples, but these were included in the principal component analysis (PCA) model creation, as this is an unsupervised technique unaffected by reference parameters.

Spectral database

A comprehensive database of Raman spectra of AGEs and ALEs was assembled. Commercially available pure compounds were purchased from NeoMPS [Strasbourg, France; hydroimidazolones Nd-(5-hydro-5-methyl-4-imidazolon-2-yl)-ornithine (MG-H1), 2-amino-5-(2-amino-5-hydro-5-methyl-4-imidazolon-1-yl)-pentanoic acid (MG-H2), and Nd-(5-hydro-4-imidazolon-2-yl)-ornithine (G-H1); CML; carboxyethyl lysine (CEL); and dihydropyridine lysine (DHP-Lys)], International Maillard Reaction Society (IMARS; Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA; pentosidine), Oxis International (Beverly Hills, CA, USA; HHE), and Sigma-Aldrich [St. Louis, MO, USA; methyl glyoxal (MGO), glyoxal (GO), glycoaldehyde, ACR, croton aldehyde (CRA), all-trans retinal, 2-aminoadipic acid (2-AAA), and methionine sulfoxide (MetSO)]. Reference samples of collagens I, III, and IV, elastin, and heme were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

MDA was prepared as described previously (35), while AGE-modified protein (BSA) was prepared according to previously described methods (36).

Other AGEs and ALEs were generously donated as indicated: 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE), Prof. Koij Uchida (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan); argpyrimidine (ARP), Prof. Ram Nagaraj (Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA); DHA and oxidized DHA, Dr. Malgorzata Rozanowska (School of Optometry and Visual Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK); α-crystallin, Dr. Tomasz Panz (Department of Biophysics, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland).

Raman microscopy

Raman spectra of AGE/ALE precursors, free adducts, and protein-modifications were measured as solids on CaF2 slides (except for ACR and CRA, which were in liquid form) using an excitation wavelength of 633 nm (20 mW). For fluorescent samples, 785-nm excitation was used to minimize background signal, and the intensity profile was corrected to that of 633 nm. All Raman spectra were recorded using a Raman confocal microscope (Horiba JY LabRam HR800, with Labspec V5 software; Jobin Yvon, Ville d'Asq, France), with a confocal hole size of 200 μm for solids (×50 objective), 400 μm (×10 objective) for solutions and 400 μm (×100 objective) for ocular tissue sections (this gave a z-axis resolution of 1.5 μm). A 300 line/mm diffraction grating was used throughout, giving a spectral resolution of 12 cm−1. Typically, spectra of solids were acquired for 10 s/point from 10 points within a sample. Resulting spectra were averaged and baseline corrected using linear interpolation between adjacent minima. For ocular tissue studies, spectra were acquired from flat mounts of Bruch's membrane/choroid for 10 s/point from selected areas (8×8 grid, 64 points in 256 μm2) within peripheral and macular regions of the sample with 3 replications/area. Resulting spectra were averaged, baseline corrected, and normalized about the heme-amide I region (1550–1690 cm−1) (37). For the larger area maps, the spectra were acquired for 2 s/point in a 250 × 250 grid at 0.25 μm spacing, covering 3900 μm2 within the macular region.

The raw Raman signal contains contributions from non-Raman optical phenomena such as fluorescence, which appear in the signal as a broad curve under the true Raman signal (38). This non-Raman background was removed from the Bruch's membrane spectra by calculating the linear combination of backgrounds identified previously (31). The previously generated multivariate models [PCA and partial least squares (PLS) regression against pentosidine] were applied to the new data in Matlab (Mathworks, Cambridge, UK) (31). No significant differences between the previous dataset and the new dataset were detected, so the two were combined to provide larger sample sets. The constituent spectral signals were extracted using PCA and tested against the database. The best fit was identified and subtracted, followed by the best fit for the residual, until no more matches were significant. In complex biological matrices, the molecule of interest often interacts with other molecules that modulate the position of the Raman bands. In such circumstances, the spectral effect of these interactions can be identified in a literature search or via controlled experiments. If the differences between the reference and the unknown signal can be explained logically, identification can be accepted. Many biochemical constituents occur in more than one PC, so in these cases the relative contribution of the constituent to each PC was used to weight the scores, which were then summed to obtain the aggregate PC score for that constituent.

The regression between age and each constituent was fitted using linear, quadratic, and exponential lines of best fit; the exponential fit did not perform significantly better than the linear fit and so was ignored based on Ockham's razor of simplicity. To distinguish the fitted equations, we denote the correlation coefficients as R2l and R2q for the linear and quadratic models, respectively. For the Raman images, the PCA scores at each point were used to create 2 intensity scales (one each for positive and negative scores) and reorganized into 2-dimensional grids using Matlab and saved in jpeg format. The PC images were then opened in Adobe Photoshop CS2 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) as separate layers and blended using screen mode to create the overlaid merged images for multiple PCs. The color channel was used to differentiate among chemical species, while the intensity scale was used to represent the relative magnitude of the PC score, which is a dimensionless number. We present the individual channels in small format with the corresponding overlay in large format. Overlap of the constituents is readily identified by the mixing of the red and green channels to produce a yellow color. The sizes of constituent deposits were measured by binarizing the relevant map in Photoshop using a threshold of 50% and measuring the length on the longest axis and the width measured at the widest point perpendicular to this axis. The lengths of the 2 axes were averaged and used to estimate the area of the equivalent circle.

RESULTS

AGE/ALE identification

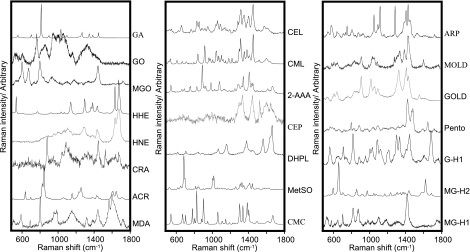

Raman spectra were recorded for a broad range of AGEs/ALEs that have been previously identified in vivo (Fig. 1). Each of the AGE/ALE species demonstrated characteristic “fingerprints,” and even very similar species could be readily differentiated. For example, CEL/CML and methylglyoxal-lysine dimer (MOLD)/glyoxal-lysine dimer (GOLD) differ by only a single methyl group, and yet their spectra were distinct (Fig. 1). These compounds could be grouped according to shared chemical structure as, for example, the carboxylated lysines (CML, CEL, and 2-AAA) or the α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (HHE, HNE, and CRA), and such groupings demonstrated spectral similarities arising from the shared molecular groups. For example, carboxylated alkyl lysines revealed very similar spectral patterns between 1200–1700 cm−1, while the α,β-unsaturated aldehydes showed a strong doublet between 1500 and 1700 cm−1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Raman spectral database of selected intermediates and final protein modifications detected in human tissues. DHPL, dihydropyridine lysine; MOLD, methylglyoxal-lysine dimer; GOLD, glyoxal-lysine dimer (GOLD); pento, pentosidine.

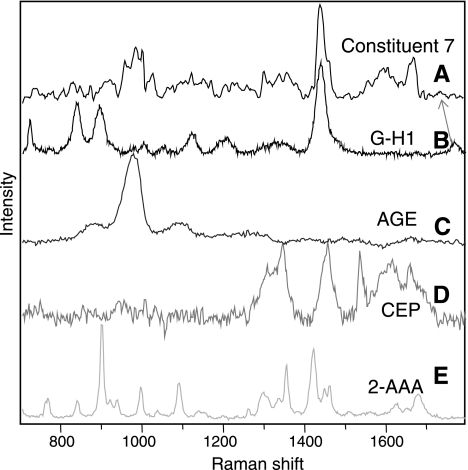

Following Raman spectroscopic analysis of human Bruch's membrane, a total of 60 unique signals were found. Some limited Raman spectra from this tissue have been reported previously by us (31), based on the AGE/ALE identification procedure described above, Bruch's membrane was analyzed specifically for these adducts and modifications. As an example of the spectral identification process, Fig. 2 displays the trace acquired for one particular constituent (constituent 7) in a Bruch's membrane tissue sample. Using the available spectral database, constituent 7 was identified as a linear combination of 4 modifications: G-H1, CEP, 2-AAA, and a generic AGE signal that was obtained using glucose-modified BSA (AGE-BSA). Some shifts in band position were observed, although these can be accounted for by physical interactions that are discussed further below. G-H1 and 2-AAA are considered to be important AGEs, whereas CEP is considered to be an important ALE (39).

Figure 2.

Comparing Raman spectra of biochemical constituent 7 (A), G-H1 (B), AGE (C), CEP (D), and 2-AAA (E). Constituent 7 can be wholly accounted for by a combination of signals from AGEs/ALEs, with some slight shifts in band position (due to matrix interactions). Biggest band shift is observed in the band most sensitive to hydrogen bonding (carbonyl stretch), suggesting strong hydrogen bonding of G-H1 in Bruch's membrane.

Variation in identified proteins

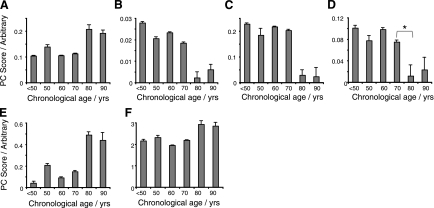

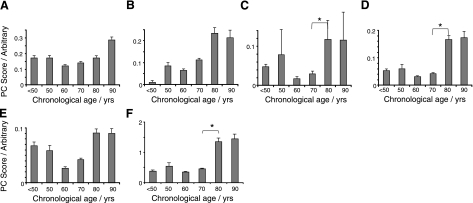

Age-related concentration variation in several Bruch's membrane protein constituents were identified from PCA of the Raman data (Fig. 3). As a complex basal lamina, Bruch's membrane contains a number of collagens, and it was observed that collagen I significantly increased with age (R2l=0.58; Fig. 3A). By contrast, collagens III and IV decreased with age (Fig. 3B, C; R2q=0.81 and 0.82, respectively). Other proteins were also altered in aged Bruch's membrane, and these included elastin (showing a decrease at age 70–80, P<0.05, R2q=0.79; Fig. 3D), α-crystallin (Fig. 3E; increase with age, R2l=0.69) and the porphyrin heme (stepwise increase with age, R2l=0.54; Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Column plots showing the changes in Raman signal levels of a range of proteins and lipids with chronological age in human Bruch's membrane. A) Collagen I (R2l=0.58; P<0.05). B) Collagen III (R2q=0.81; P<0.05). C) Collagen IV (R2q=0.82; P<0.05). D) Elastin (R2q=0.73; P<0.05). *Significant change between bracketed groups (P<0.05). E) α-Crystallin (R2q=0.73; P<0.05). F) Heme (R2l=0.54; P<0.05).

Variation in identified lipids

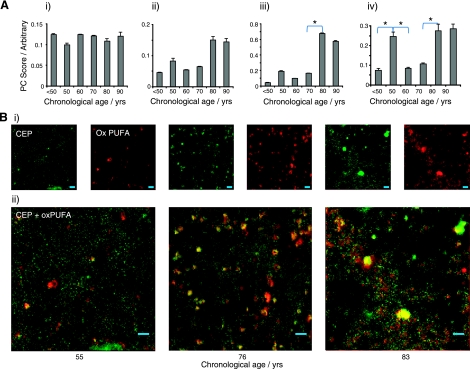

A number of lipid-related changes were also observed in aged Bruch's membrane (Fig. 4). While unoxidized monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA)-based lipids in Bruch's membrane showed no significant age-related trends (R2l=0.00; Figure 4Ai), cholesterol showed a stepwise increase with aging (R2q=0.74, P<0.05 between 70 and 80; Fig. 4Aii). Oxidized PUFA is a known modification in the aging retina (40–46), and Raman analysis demonstrated an age-related increase in Bruch's membrane (R2l=0.60; Fig. 4Aiii). DHA-derived CEP showed an increase between 70 and 80 (P<0.05; Table 1) but also showed marked elevation in the 50s group (P<0.05; Fig. 4Aiv). The distribution maps of CEP (Fig. 4Bi) and oxidized PUFAs (Fig. 4Bii) both revealed diffuse accumulation in Bruch's membrane with age, but the majority of these constituents were localized to intense spots within the tissue that grew from a mean size of 6 to 25 μm2 (2.8–5.7 μm in diameter) between the youngest and oldest donors studied (37 and 92 yr old). Merging the two channels demonstrated colocalization between CEP and oxidized PUFAs (Fig. 4Bii).

Figure 4.

A) Quantity of MUFAs (R2q=0.00; NS; i), cholesterol (R2q=0.74; P<0.05; ii), oxidized PUFAs (R2q=0.73; P<0.05; iii), and G-H1/CEP/AGE/2-AAA (R2q=0.44; NS; iv) in each decade, as predicted from PCA of Raman data. B) Raman maps showing the distribution of CEP (green) and oxidized PUFA (red) in donor eyes from 55-, 76-, and 83-yr-old females (i) and overlaid merge of the CEP and oxidized PUFAs (ii; yellow results from overlap of red and green). Scale bars = 5 μm. Intensity of images is related to magnitude of PC score (arbitrary units). *Significant change between bracketed groups (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Age dependence of biochemical constituents identified in the Raman signal of human donor Bruch's membrane

| Constituent | R2 (linear) | R2 (quadratic) | t Test, 70 vs. 80 | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heme | 0.54* | 0.70 | NS | ↑ |

| MUFAs | 0 | 0.00 | NS | NS |

| Cholesterol | 0.68* | 0.74* | * | ↑ |

| HHE | 0.33 | 0.57 | * | ↑ |

| CML | 0.31 | 0.89** | NS | ↑ |

| CEL | 0.86 | 0.86* | NS | ↑ |

| GO | 0.22 | 0.69 | NS | NS |

| G-H1/CEP | 0.39 | 0.44 | * | ↑ |

| DHP-Lys | 0.60* | 0.81* | * | ↑ |

| Pentosidine | 0.87* | 0.75* | * | ↑ |

| Oxidized PUFAs | 0.60* | 0.73 | NS | ↑ |

| Collagen I | 0.58* | 0.65 | NS | ↑ |

| Collagen III | 0.81* | 0.81* | NS | ↓ |

| Collagen IV | 0.71* | 0.82* | NS | ↓ |

| Elastin | 0.73* | 0.73 | * | ↓ |

| α-Crystallin | 0.69* | 0.73 | NS | ↑ |

Trend plots against age were fitted with linear and quadratic best-fit lines. Direction of the trend is indicated for age. ↑, increasing; ↓, decreasing; NS, nonsignificant.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

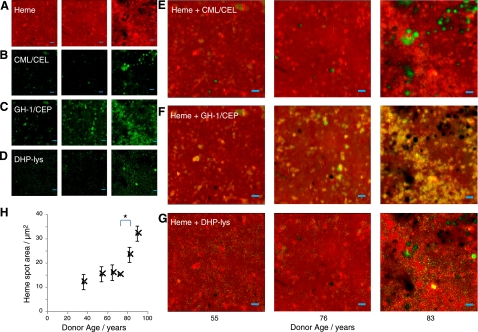

Heme was observed to have a uniform flat-field concentration across Bruch's membrane but with a number of “hotspots” (Fig. 5A) that grow with age from a mean size of 12 μm2 in the youngest donors studied to 32 μm2 in the oldest (3.6–6 μm in diameter). Interestingly, some gaps in the heme background begin to appear and grow even as the heme is accumulating in large hotspots, increasing from a mean size of 6 μm2 to 26 μm2 (2.8–5.8 μm diameter) between the youngest and oldest donors studied. These gaps were highly coincident with deposits of CML and CEL (Fig. 5A, B, E). In contrast, the distribution of G-H1 (Fig. 5A, C, F) was colocalized with the heme hotspots, and this was enhanced with age. DHP-Lys exhibited different distribution again (Fig. 5A, D, G) and did not colocalize with heme. In addition to G-H1, the ALE precursor and modification HHE and CEP exhibited extensive colocalization with the heme, while the distribution of GO did not appear related to heme or to any of the other constituents measured. Distribution maps for all the AGEs and ALEs identified are available in the Supplemental Data.

Figure 5.

A–G) Raman distribution maps in human donor Bruch's membranes of heme (A), CML/CEL (B), G-H1/CEP (C), DHP-Lys (D), and the overlaid merge of these channels (yellow results from overlap of red and green); heme and CML/CEL (E), heme and G-H1 (F), and heme and DHP-Lys (G). Heme is colocalized with G-H1/CEP, excluded by CML/CEL, and has no consistent spatial relationship with DHP-Lys. H) Mean area of heme deposits against age; significant increase between 70s and 80s. *Significant change between bracketed groups (P<0.05). Scale bars = 5 μm. Intensity of images is related to magnitude of PC score (arbitrary units).

Variation in identified AGEs/ALEs

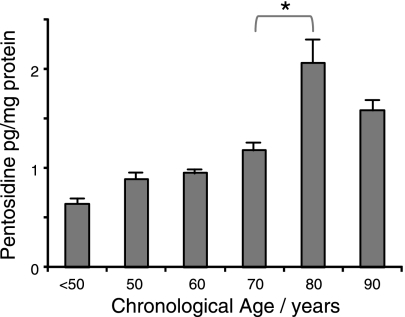

Eight AGE/ALE modifications identified in the database were present in the Raman signals of Bruch's membrane, and many showed increased accumulation with chronological age (Fig. 6 and Table 1). When these modifications were aggregated to produce a single AGE/ALE plot, a clear age-related increase was apparent (R2q=0.88; Fig. 6F). As with some of the Raman spectra associated with defined proteins and lipids, a marked rise was observed between donors aged 70 and 80. The pentosidine prediction model described previously (31) was also applied to the Raman data, and it was demonstrated that the level of this AGE cross-link increased steadily and significantly with chronological age, with R2l = 0.87 (Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

Raman-PCA predicted AGE/ALE content of human Bruch's membrane against chronological age. A) CML. B) CEL (R2q=0.88; P<0.01). C) HHE (R2q=0.57; NS). D) DHP-Lys (R2q=0.81; P<0.05). E) GO (R2q=0.69; NS). F) Aggregate Raman-PCA predicted AGE/ALE content (R2q=0.88; P<0.01). *Significant change between bracketed groups (P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Scatterplot of Raman-predicted pentosidine level vs. chronological age for human donor Bruch's membranes (R2l = 0.87; P < 0.05). *Significant change between bracketed groups (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

A range of defined AGEs/ALEs is known to occur in vivo, and many of these have been localized to and/or quantified in defined tissues, including some ocular structures (21, 23, 31, 47, 48). These modifications form a highly heterogeneous group, and this is reflected in the range of spectral signals obtained. The current study demonstrates that each AGE/ALE modification has spectral features that are common to particular structural groups, although even closely related modifications such as CML and CEL still display distinguishable spectra. We have previously published a more detailed account of the relationship between the Raman spectra and chemical structure of some modifications (CML, CEL, AAA, HNE, CRA, and ACR) (32). Such data illustrate the utility of Raman spectroscopy as a molecular fingerprinting technique and, in particular, highlight the potential for rapid, nondestructive determination of different AGE/ALE modifications in complex biological samples.

A comprehensive spectral database, as provided in this study, is critical to molecular identification. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the only pronounced shift in Raman band positions between reference and observed signals was the carbonyl-stretching mode in G-H1, which shifted from 1750 to 1730 cm−1, which is well within the typical range between 1550 and 1800 cm−1 (49). This position is inversely related to hydrogen bonding strength and suggests that in a complex protein matrix such as Bruch's membrane, G-H1 engages in stronger hydrogen bonding with the potential to alter the physicochemical nature of the constituent proteins.

Using a multiplex approach, the current study has tracked variations simultaneously in ∼60 individual biochemical constituents of human Bruch's membrane, and these have been presented as age-related modifications to proteins and lipids. Bruch's membrane consists mainly of an inner layer of elastin surrounded by collagen types I, III, and V, with the outermost layers on both apical and basal sides (RPE and choriocapillaris) containing high levels of basement membrane proteins such as collagen IV (50). It has been suggested that AGE-modification of the collagen IV α3–5 isoforms renders them resistant to proteolysis, which might promote early basal deposit formation during aging (51, 52). Our results show that, in contrast to collagen I, which increases with age, the levels of collagen IV and III are significantly reduced in aged Bruch's membrane (Fig. 3). Interestingly, age-related reduction in collagen IV has been observed in Bruch's membrane (53, 54). Elastin is another important Bruch's membrane structural protein embedded within the central layer and adding to flexibility of the matrix. Our Raman-based analysis indicates reduced elastin in Bruch's membrane from older donors and this ties in with previous reports demonstrating loss of integrity and elastic layer abnormalities from individuals with early and advanced AMD (55–57).

The Raman data in the current study suggest an age-related increase in Bruch's membrane lipid deposition, particularly oxidized PUFAs. In view of the highly oxidative environment of the outer retina and the RPE's role in clearing lipoxidation products, it would be expected that a significant proportion of the PUFAs would indeed be oxidized at the Bruch's membrane, and indeed little unoxidized DHA is found in the Bruch's membrane (14). The presence of UC has been shown in the retina, Bruch's membrane, and choroid, while EC accumulates with age, almost exclusively in Bruch's membrane (10, 11). Our data obtained by a completely different analytical approach confirm this and suggest that accumulation of total cholesterols is age-dependent. It has been suggested that a toxic metabolite of cholesterol (7-ketocholesterol) could have a pathogenic role in AMD (12, 13).

In addition to structural proteins, α-crystallin and heme were also identified in Bruch's membrane by their Raman signatures. There was a marked age-related up-regulation of α-crystallin, and this trend has also been observed in association with progressive ultrastructural aging of the RPE-choroid (58). Furthermore, α-crystallin is detected more frequently in drusen of AMD-donors when compared to age-matched, nondiseased controls (17).

This study has demonstrated that Raman spectroscopy can identify and quantify age-related changes in a critically important ocular structure with a single nondestructive measurement. This points to the possibility of using Raman spectroscopy to measure age-related changes in vivo. Indeed, multiplexed analysis of pathogenic molecules during the course of aging could lead to enhanced understanding of ocular disease genesis and progression, perhaps enabling a greater degree of predictability for individuals with higher risk of ocular disease and optimization of therapy.

From a biochemical perspective, the most important result in this study is the first-ever directly recorded evidence of the central role of heme in the formation of certain AGEs and ALEs within the human Bruch's membrane. Heme has been demonstrated previously by Raman spectroscopy and immunostaining in Bruch's membrane (31, 59), and our Raman analysis shows age-related increases in heme deposits within the matrix. This finding is significant since advanced glycation of this enzyme is known to promote the release of its iron ion, which, in turn, can catalyze formation of free radicals (60) and, ultimately, more AGEs/ALEs. Indeed the presence of 2-AAA is indicative of this mechanism, as it is formed through the action of H2O2 on allysine; i.e., the signature of protein carbonyl oxidation (61). The data presented in the current study suggest that heme colocalizes with both oxidized PUFAs and with CEP, an ALE that is more strongly elevated in AMD donor tissue than in controls (47). A role for porphryn-mediated oxidation of lipids has been shown previously in the lung (62), and this, combined with the colocalization of ALEs with heme, suggests that in the Bruch's membrane heme might be involved in regulating lipid waste products from the RPE. Consequently, heme plays a central role in the formation of the collagen modifications in Bruch's membrane that disrupt its function and are ultimately implicated in vision loss (24).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (G0600053), the Leverhume Trust (EM/2006/0049), the Research and Development Office of Northern Ireland (SPI/2384/03), and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (ES011985). Purchase of the Raman microscope was assisted by funding from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (JREI 18471). The authors also thank the Bristol Eye Bank (Bristol, UK) for the donation of clinical material used in this study. Creation of the AGE/ALE database was dependent on the generosity of several individuals: Prof. Uchida (Nagoya University, Japan), Prof. Nagaraj (Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA), and Dr. Rozanowska (School of Optometry and Visual Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK).

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klein R., Klein B. E., Tomany S. C., Meuer S. M., Huang G. H. (2002) Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam eye study. Ophthalmology 109, 1767–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding J. J. (1991) Cataract: Biochemistry, Epidemiology and Pharmacology, Chapman & Hall, London, UK [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jong P. T. (2006) Age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 1474–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty S., Koh H., Phil M., Henson D., Boulton M. (2000) The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, 115–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starita C., Hussain A. A., Pagliarini S., Marshall J. (1996) Hydrodynamics of ageing Bruch's membrane: implications for macular disease. Exp. Eye Res. 62, 565–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binder S., Stanzel B. V., Krebs I., Glittenberg C. (2007) Transplantation of the RPE in AMD. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 26, 516–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ethier C. R., Johnson M., Ruberti J. (2004) Ocular biomechanics and biotransport. Ann. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 6, 249–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambati J., Ambati B. K., Yoo S. H., Ianchulev S., Adamis A. P. (2003) Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Surv. Ophthalmol. 48, 257–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulton M., Roanowska M., Wess T. (2004) Ageing of the retinal pigment epithelium: implications for transplantation. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 242, 76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudolf M., Curcio C. A. (2009) Esterified cholesterol is highly localized to Bruch's membrane, as revealed by lipid histochemistry in wholemounts of human choroid. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 731–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curcio C. A., Millican C. L., Bailey T., Kruth H. S. (2001) Accumulation of cholesterol with age in human Bruch's membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 265–274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Javitt N. B., Javitt J. C. (2009) The retinal oxysterol pathway: a unifying hypothesis for the cause of age-related macular degeneration. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 20, 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreira E. F., Larrayoz I. M., Lee J. W., Rodriguez I. R. (2009) 7-Ketocholesterol is present in lipid deposits in the primate retina: potential implication in the induction of VEGF and CNV formation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 523–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L., Li C. M., Rudolf M., Belyaeva O. V., Chung B. H., Messinger J. D., Kedishvili N. Y., Curcio C. A. (2009) Lipoprotein particles of intraocular origin in human Bruch membrane: an unusual lipid profile. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 870–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazan N. G. (1982) Metabolism of phospholipids in the retina. Vis. Res. 22, 1539–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Januszewski A. S., Alderson N. L., Metz T. O., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. (2003) Role of lipids in chemical modification of proteins and development of complications in diabetes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 1413–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crabb J. W., Miyagi M., Gu X., Shadrach K., West K. A., Sakaguchi H., Kamei M., Hasan A., Yan L., Rayborn M. E., Salomon R. G., Hollyfield J. G. (2002) Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 14682–14687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu J., Pauer G. J., Yue X., Narendra U., Sturgill G. M., Bena J., Gu X., Peachey N. S., Salomon R. G., Hagstrom S. A., Crabb J. W. (2009) Assessing susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration with proteomic and genomic biomarkers. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 1338–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schutt F., Bergmann M., Holz F. G., Kopitz J. (2003) Proteins modified by malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, or advanced glycation end products in lipofuscin of human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 3663–3668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howes K. A., Liu Y., Dunaief J. L., Milam A., Frederick J. M., Marks A., Baehr W. (2004) Receptor for advanced glycation end products and age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 3713–3720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handa J. T., Verzijl N., Matsunaga H., Aotaki-Keen A., Lutty G. A., Koppele J. M. T., Miyata T., Hjelmeland L. M. (1999) Increase in the advanced glycation end product pentosidine in Bruch's membrane with age. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40, 775–779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada Y., Ishibashi K., Bhutto I. A., Tian J., Lutty G. A., Handa J. T. (2006) The expression of advanced glycation endproduct receptors in rpe cells associated with basal deposits in human maculas. Exp. Eye Res. 82, 840–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishibashi T., Murata T., Hangai M., Nagai R., Horiuchi S., Lopez P. F., Hinton D. R., Ryan S. J. (1998) Advanced glycation end products in age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 116, 1629–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glenn J. V., Stitt A. W. (2009) The role of advanced glycation end products in retinal ageing and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Sub. 1790, 1109–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein P. S., Zhao D. Y., Wintch S. W., Ermakov I. V., McClane R. W., Gellermann W. (2002) Resonance Raman measurement of macular carotenoids in normal subjects and in age-related macular degeneration patients. Ophthalmology 109, 1780–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beattie J. R., Brockbank S., McGarvey J. J., Curry W. J. (2005) Effect of excitation wavelength on the Raman spectroscopy of the porcine photoreceptor layer from the area centralis. Mol. Vis. 11, 825–832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beattie J. R., Brockbank S., McGarvey J. J., Curry W. J. (2007) Raman microscopy of porcine inner retinal layers from the area centralis. Mol. Vis. 13, 1106–1113 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sideroudi T. I., Pharmakakis N. M., Papatheodorou G. N., Voyiatzis G. A. (2006) Non-invasive detection of antibiotics and physiological substances in the aqueous humor by Raman spectroscopy. Lasers Surg. Med. 38, 695–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shih S., Weng Y. M., Chen S. L., Huang S. L., Huang C. H., Chen W. L. (2003) FT-Raman spectroscopic investigation of lens proteins of tilapia treated with dietary vitamin E. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 420, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borchman D., Ozaki Y., Lamba O. P., Byrdwell W. C., Czarnecki M. A., Yappert M. C. (1995) Structural characterization of clear human lens lipid-membranes by near-infrared fourier-transform Raman-spectroscopy. Curr. Eye Res. 14, 511–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glenn J. V., Beattie J. R., Barrett L., Frizzell N., Thorpe S. R., Boulton M. E., McGarvey J. J., Stitt A. W. (2007) Confocal Raman microscopy can quantify advanced glycation end product (AGE) modifications in Bruch's membrane leading to accurate, nondestructive prediction of ocular aging. FASEB J. 21, 3542–3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawlak A. M., Beattie J. R., Glenn J. V., Stitt A. W., McGarvey J. J. (2008) Raman spectroscopy of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), possible markers for progressive retinal dysfunction. J. Raman Spectrosc. 39, 1635–1642 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawlak A. M., Glenn J. V., Beattie J. R., McGarvey J. J., Stitt A. W. (2008) Advanced glycation as a basis for understanding retinal aging and noninvasive risk prediction. Proc. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1126, 59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rozanowska M., Jarvis-Evans J., Korytowski W., Boulton M. E., Burke J. M., Sarna T. (1995) Blue light-induced reactivity of retinal age pigment. In vitro generation of oxygen reactive species. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18825–18830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suttnar J., Cermak J., Dyr J. E. (1997) Solid-phase extraction in malondialdehyde analysis. Anal. Biochem. 249, 20–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stitt A. W., Li Y. M., Gardiner T. A., Bucala R., Archer D. B., Vlassara H. (1997) Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) co-localize with AGE receptors in the retinal vasculature of diabetic and of AGE-infused rats. Am. J. Pathol. 150, 523–531 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beattie J. R., Glenn J. V., Boulton M. E., Stitt A. W., McGarvey J. J. (2009) Effect of signal intensity normalization on the multivariate analysis of spectral data in complex “real-world” datasets. J. Raman Spectrosc. 40, 429–435 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beattie R. J., Bell S. J., Farmer L. J., Moss B. W., Desmond P. D. (2004) Preliminary investigation of the application of Raman spectroscopy to the prediction of the sensory quality of beef silverside. Meat Sci. 66, 903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monnier V. M. (2003) Intervention against the Maillard reaction in vivo. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 419, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu X., Sun M., Gugiu B., Hazen S., Crabb J. W., Salomon R. G. (2003) Oxidatively truncated docosahexaenoate phospholipids: total synthesis, generation, and peptide adduction chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 68, 3749–3761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollyfield J. G., Bonilha V. L., Rayborn M. E., Yang X., Shadrach K. G., Lu L., Ufret R. L., Salomon R. G., Perez V. L. (2008) Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Med. 14, 194–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hollyfield J. G., Perez V. L., Salomon R. G. (2010) A hapten generated from an oxidation fragment of docosahexaenoic acid is sufficient to initiate age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 41, 290–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long E. K., Picklo M. J., Sr. (2010) Trans-4-hydroxy-2-hexenal, a product of n-3 fatty acid peroxidation: make some room HNE. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanito M., Brush R. S., Elliott M. H., Wicker L. D., Henry K. R., Anderson R. E. (2009) High levels of retinal membrane docosahexaenoic acid increase susceptibility to stress-induced degeneration. J. Lipid Res. 50, 807–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.SanGiovanni J. P., Chew E. Y. (2005) The role of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in health and disease of the retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 24, 87–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bazan N. G. (1989) The metabolism of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the eye: the possible role of docosahexaenoic acid and docosanoids in retinal physiology and ocular pathology. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 312, 95–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu X., Meer S. G., Miyagi M., Rayborn M. E., Hollyfield J. G., Crabb J. W., Salomon R. G. (2003) Carboxyethylpyrrole protein adducts and autoantibodies, biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42027–42035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karachalias N., Babaei-Jadidi R., Rabbani N., Thornalley P. J. (2010) Increased protein damage in renal glomeruli, retina, nerve, plasma and urine and its prevention by thiamine and benfotiamine therapy in a rat model of diabetes. Diabetologia 53, 1506–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beattie J. R., Bell S. J., Moss B. W. (2004) A critical evaluation of Raman spectroscopy for the analysis of lipids: fatty acid methyl esters. Lipids 39, 407–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guymer R., Luthert P., Bird A. (1999) Changes in Bruch's membrane and related structures with age. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 18, 59–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marshall G. E., Konstas A. G. P., Reid G. G., Edwards J. G., Lee W. R. (1992) Type-Iv collagen and laminin in Bruch membrane and basal linear deposit in the human macula. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 76, 607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marshall G. E., Konstas A. G. P., Reid G. G., Edwards J. G., Lee W. R. (1994) Collagens in the aged human macula. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 232, 133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen L., Miyamura N., Ninomiya Y., Handa J. T. (2003) Distribution of the collagen IV isoforms in human Bruch's membrane. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 87, 212–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pauleikhoff D., Wojteki S., Muller D., Bornfeld N., Heiligenhaus A. (2000) Adhesive properties of basal membranes of Bruch's membrane: immunohistochemical analysis of aging changes in adhesive proteins and lipids. Ophthalmologe 97, 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chong N. H., Keonin J., Luthert P. J., Frennesson C. I., Weingeist D. M., Wolf R. L., Mullins R. F., Hageman G. S. (2005) Decreased thickness and integrity of the macular elastic layer of Bruch's membrane correspond to the distribution of lesions associated with age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 241–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang J. D., Presley J. B., Chimento M. F., Curcio C. A., Johnson M. (2007) Age-related changes in human macular Bruch's membrane as seen by quick-freeze/deep-etch. Exp. Eye Res. 85, 202–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skeie J. M., Mullins R. F. (2008) Elastin-mediated choroidal endothelial cell migration: possible role in age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 5574–5580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian J., Ishibashi K., Ishibashi K., Reiser K., Grebe R., Biswal S., Gehlbach P., Handa J. T. (2005) Advanced glycation endproduct-induced aging of the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid: a comprenensive transcriptional response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 11846–11851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tezel T. H., Geng L. J., Lato E. B., Schaal S., Liu Y. Q., Dean D., Klein J. B., Kaplan H. J. (2009) Synthesis and secretion of hemoglobin by retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 1911–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sen S., Kar M., Roy A., Chakraborti A. S. (2005) Effect of nonenzymatic glycation on functional and structural properties of hemoglobin. Biophys. Chem. 113, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sell D. R., Strauch C. M., Shen W., Monnier V. M. (2007) 2-aminoadipic acid is a marker of protein carbonyl oxidation in the aging human skin: effects of diabetes, renal failure and sepsis. Biochem. J. 404, 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beattie J. R., Maguire C., Gilchrist S., Barrett L. J., Cross C. E., Possmayer F., Ennis M., Elborn J. S., Curry W. J., McGarvey J. J., Schock B. C. (2007) The use of Raman microscopy to determine and localize vitamin E in biological samples. FASEB J. 21, 766–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.