Abstract

The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a basic cellular process that plays a key role in normal embryonic development and in cancer progression/metastasis. Our previous study indicated that EMT processes of mouse and human epithelial cells induced by TGF-β display clear reduction of gangliotetraosylceramide (Gg4) and ganglioside GM2, suggesting a close association of glycosphingolipids (GSLs) with EMT. In the present study, using normal murine mammary gland (NMuMG) cells, we found that levels of Gg4 and of mRNA for the UDP-Gal:β1–3galactosyltransferase-4 (β3GalT4) gene, responsible for reduction of Gg4, were reduced in EMT induced by hypoxia (∼1% O2) or CoCl2 (hypoxia mimic), similarly to that for TGF-β-induced EMT. An increase in the Gg4 level by its exogenous addition or by transfection of the β3GalT4 gene inhibited the hypoxia-induced or TGF-β-induced EMT process, including changes in epithelial cell morphology, enhanced motility, and associated changes in epithelial vs. mesenchymal molecules. We also found that Gg4 is closely associated with E-cadherin and β-catenin. These results suggest that the β3GalT4 gene, responsible for Gg4 expression, is down-regulated in EMT; and Gg4 has a regulatory function in the EMT process in NMuMG cells, possibly through interaction with epithelial molecules important to maintain epithelial cell membrane organization.—Guan, F., Schaffer, L., Handa, K., and Hakomori, S. Functional role of gangliotetraosylceramide in epithelial- to-mesenchymal transition process induced by hypoxia and by TGF-β.

Keywords: cobalt chloride, epithelial molecule, gene transfection, glycogene, glycosphingolipid

It is generally known that cells are capable of changing their phenotype, including morphology, growth behavior, adhesion characteristics, and motility, when they encounter a different microenvironment. One well-studied process is the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which was originally identified as an essential cellular mechanism at several specific stages in ontogenic development (1–4). The EMT process is characterized by a decrease in epithelial cell markers [e.g., E-cadherin (Ecad)], an increase in mesenchymal cell markers [e.g., vimentin and fibronectin (FN)], a morphological change from epithelial cells to motile fibroblastic cells, and enhanced cell motility. There is increasing evidence that the EMT process plays a key role in cancer progression and metastasis (for review, see refs. 5, 6) and in fibrosis-related diseases (7–10).

Previous studies by our group and others have shown that glycosphingolipids (GSLs) interact with growth factor receptors, integrins, signal transducers, tetraspanins, and caveolin, organized at the “glycosynaptic domain,” which is characterized by resistance to detergent Brij 58 or 98 at 4°C and separable as a low-density fraction (11–14). GSLs complexed with various membrane components as above, in such a microdomain, modulate cell growth, adhesion, motility, and apoptosis (for review see refs. 15–19). Despite increasing evidence for the role of GSLs in modulating a variety of physiological and pathobiological processes, little attention has been paid to possible changes in GSLs in the EMT process and their functional role.

Our previous study, focused on GSL changes associated with the EMT process induced by TGF-β in mouse and human epithelial cells, indicated that gangliotetraosylceramide (Gg4) or ganglioside GM2 is reduced or deleted and that preincubation of cells with these GSLs, particularly Gg4, inhibited the EMT process (20). However, the functional significance of Gg4 and its inhibitory effect were not clearly identified. Initial studies with “glycogene chip analysis” clearly indicated that Gg4 expression was down-regulated in the EMT process induced by TGF-β.

In the present study, we investigated the EMT process induced by factors other than TGF-β to further clarify the functional role of Gg4 in the EMT process in NMuMG cells. Because hypoxia (10, 21), its mimetic CoCl2 (22), or the hypoxia-associated signaling process (23–27) has been shown to induce an EMT process similar to that induced by TGF-β (28), we examined changes in Gg4, its synthase, and its gene associated with the hypoxia-induced EMT process. The present findings further elucidate the functional role of Gg4, its synthase, and its gene in defining the EMT process and suggest possible future application of GSLs to interfere with metastatic progression of carcinomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and cell culture

Normal mouse mammary gland epithelial (NMuMG) cells were cultured as described previously (20). In most experiments, NMuMG cells were cultured overnight in the culture medium under the normoxia condition (5% CO2/95% air) to get monolayer cells with ∼30% confluence and then were cultured at 37°C for a further 48 h in fresh culture medium alone in the presence of TGF-β (2 ng/ml) (28) or in the presence of CoCl2 (100 μM) (22). For hypoxia-treated cells, the monolayer cells were cultured in fresh culture medium in a hypoxia incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Inc., Del Mar, CA, USA) containing 1% O2/5% CO2/94% N2, for 48 h at 37°C.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies

Mouse anti-Gg4 IgM mAb TKH7 (29), mouse anti-fucosyl-GM1 (FucGM1) IgG3 mAb TKH5 (30), and mouse anti-Gg3 IgM mAb 2D4 (31) were established in this laboratory. Other antibodies and products were obtained as follows: GD1a-1 and anti-GD1a (from Dr. Ronald L. Schnaar, Departments of Pharmacology and Neurology, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA) (32); mouse anti-Ecad IgG1 and mouse anti-β-catenin IgG1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); mouse anti-N-cadherin (Ncad) IgG1 and rabbit anti-desmoplakin IgG, protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); mouse anti-FN mAb IgG1 (Calbiochem/Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); mouse anti-HIF-2α mAb IgG1 and mouse anti-HIF-1α mAb IgG2b (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA); mouse anti-occludin IgG1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); anti-ZONAB (ZO-1 associated nucleic acid-binding protein) and rabbit antiserum (Upstate Chemicon/Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA); mouse anti-vimentin IgM and anti-γ-tubulin IgG1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); rabbit anti-β3GalT4 IgG (ProteinTech, Chicago, IL, USA); Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA); horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG and HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgM (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA); and FITC-labeled goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgM+IgG (BioSource, Camarillo, CA, USA).

Reagents

GSLs [GM1, GM2, GM3, GD1a, Gg4 (asialo-GM1), Gg3 (asialo-GM2), and FucGM1] were from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA, USA). CoCl2 and cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) conjugated with biotin were from Sigma-Aldrich. TGF-β1 was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, unless described otherwise.

Isolation of total RNA

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Cell Shredder and an RNeasy Minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Highly purified RNA (A260/A280>1.8) was used.

Glycogene chip analysis

Total RNAs were analyzed by Gene Microarray Core E, Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG), Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA, USA). RNA was labeled using the MessageAmp II-Biotin Enhanced Amplification Kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA). Hybridization and scanning to the GlycoV4 chip were performed using the recommended protocols of Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA) (33). The GlycoV4 oligonucleotide array is a custom Affymetrix GeneChip designed for CFG (http://www.functionalglycomics.org). The GlycoV4 focused array includes probes for ∼1200 mouse probe IDs related to glycogenes. Affymetrix chips were scanned using the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000. Chips used for analysis had a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 3′/5′ ratio < 1.5. The raw expression values were normalized using a robust multichip average (RMA) expression summary (34, 35). All processing of the data was performed within the Bioconductor project and the R program software (available as free software under the terms of the Free Software Foundation; http://www.gnu.org/). Fold changes and ses were estimated by fitting a linear model for each gene, and empirical Bayes smoothing was applied to the ses for all of the samples at the same time (36, 37). The linear modeling approach and empirical Bayes statistics as implemented in the Limma package in R software were used for differential expression analysis. Statistics were obtained for transcripts with the multiple testing adjusted (38) P value level of 0.05. Filtering was performed so that probe sets with a fold change of <1.4 were excluded from the results. Comparisons were performed between control and TGF-β-treated NMuMG cells.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer [1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM PMSF, and 0.076 U/ml aprotinin]. Protein content was determined, and lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot as described previously (20, 39).

Determination of cell motility

Phagokinetic gold sol assay

This assay was performed as described previously (13, 20, 40, 41). Cells were cultured and treated as described above. After detachment with trypsin/EDTA, 5 × 103 cells were seeded onto gold sol-coated wells (24-well plates) in the culture medium. After an 8-h incubation at 37°C under the normoxia condition, photos were taken, and the track area of 30 cells was measured with the Scion Image program (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD, USA); results are expressed as squared pixels, as described previously (20).

Wound assay

This assay was performed by the procedure described previously without FN coating (42), based on a modification of the original method (43). NMuMG cells (2×104/well) were cultured in 24-well plates overnight and treated as described above. A pipette tip was used to scratch 3 separate wounds on the monolayers in each well, moving perpendicularly to a line drawn at the bottom of the plate. Cells were rinsed with fresh serum-free medium twice, and culture medium was added. Wounds at the marked lines were photographed. After an 8-h incubation at 37°C under normoxia, cells were washed with PBS, fixed, and stained with 1% toluidine blue. Photos of wounds at the marked lines were taken and used to calculate the area occupied by moving cells.

Cell staining

NMuMG cells (2×104) were cultured on 12-mm-diameter glass coverslips in 24-well plates and treated as described above. The cells were stained and observed as described previously (20).

GSLs were extracted from the cells treated as described above, separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPTLC), and analyzed by immunostaining for Gg4 and Gg3 and by binding with cholera toxin for GM1, as described previously (20).

RT-PCR for β3GalT4

Total RNA isolated as above was further treated with an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen) to eliminate possible contaminating genomic DNA. cDNA was synthesized from the total RNA preparation using SuperScript III First-Strand Super Mix (Invitrogen) with oligo(dT). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by using inventoried TaqMan gene expression assays and Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), with the following protocol: denaturation by a hot start at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of a 2-step program (denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min). Assay numbers were as follows: Mm00546324 for β3GalT4 and Mm02619580 for β-actin (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time PCR data were analyzed using the comparative Ct method (44).

Construct of β3GalT4 expression vector and transient transfection into NMuMG cells

The protein-coding region of the β3GalT4 gene was amplified by PCR with 5′-primer containing an NheI site (5′-CTAGCTAGCTAGCATGCCCCTCAGCCTCTT) and 3′-primer containing an EcoRI site (5′-CGGAATTCCGGGGTTCTCAGCTACTGAACCAG) using cDNA prepared from NMuMG cells. The PCR product was digested with NheI and EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) and ligated into vector pIRES-puro3 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The constructed plasmid was transiently transfected into NMuMG cells using FuGene 6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Immunoprecipitation

Postnuclear fraction (PNF) was obtained as described previously (45–47). In brief, NMuMG cells were harvested and lysed in Brij 98 lysis buffer [1% Brij 98, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, and 0.076 U/ml aprotinin] using a Dounce homogenizer with 10 strokes. The lysate was centrifuged at 2500 rpm to obtain PNF. PNF was precleared by addition of protein A/G agarose beads (50-μl bed volume) and incubation of the mixture at 4°C for 1 h. Five micrograms of antibody or control mouse IgG was mixed with protein A/G agarose beads (200-μl bed volume) for 3 h. After washing, the antibody-coated beads were mixed with 1 ml of PNF containing 1 mg of protein at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed and extracted with 2 ml of isopropanol/hexane/water (55:25:20) for GSL analysis as described previously (20) or boiled with Laemmli sample buffer for 10 min for Western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by t test using the Prism 3 program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences in results were considered significant for values of P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Change in glycogene expression in NMuMG cells after TGF-β treatment

We found previously that TGF-β treatment reduced expression of GSL Gg4 in NMuMG cells (20). To identify the gene responsible for such a reduction, expression patterns of glycogenes (glycosyltransferases, glycosidases, and others) were compared between TGF-β-treated and nontreated cells. Among 1246 mouse genes that are covered in GlycoV4 chips (see Materials and Methods), a total of 310 genes were identified as being differentially expressed (>1.4-fold change, P<0.05): 163 genes down-regulated and 147 genes up-regulated, respectively (Supplemental Data).

Among the differentially expressed genes, 24 genes (listed in Table 1) are involved in metabolism of GSLs. Other genes involved in metabolism of GSLs and covered in the glycogene chip but found to be unaffected by TGF-β treatment are not included in Table 1 or the Supplemental Data, e.g., gene ST3GAL5 for GM3 synthase.

Table 1.

Change in glycogene expression in TGF-β-treated NMuMG cells

| Gene name | Fold change | Gene description | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated after TGF-β treatment | |||

| ST8SIA4 | 0.05 | CMP-N-acetylneuraminate-poly-α2,8-sialyltransferase 4 | NM_009183.1 |

| UGT8 | 0.14 | UDP-galactose-ceramide galactosyltransferase 8 | NM_011674.4 |

| FUT9 | 0.19 | GDP-Fuc:LacNAc-α1,3-fucosyltransferase 9 (Lewis X synthase) | NM_010243.3 |

| ST3GAL4 | 0.32 | CMP-NeuAc:β-galactoside α2,3-sialyltransferase 4 | NM_009178.3 |

| ST3GAL1 | 0.34 | CMP-NeuAc:β-galactoside α2,3-sialyltransferase 1 | NM_009177.4 |

| NEU2 | 0.36 | Neuraminidase 2 | NM_015750.2 |

| β4GALT6 | 0.38 | UDP-Gal:β-GlcNAc β1,4-galactosyltransferase 6 | NM_019737.1 |

| ST3GAL6 | 0.38 | CMP-NeuAc:β-galactoside α2,3-sialyltransferase 6 | NM_018784.2 |

| β3GNT3 | 0.47 | UDP-GlcNAc:βGal β1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 3 | NM_028189.2 |

| β4GALNT1 | 0.51 | UDP-Gal:β-GlcNAc β1,4-galactosyltransferase 1 (GM2/GD2 synthase) | NM_008080.4 |

| FUT2 | 0.51 | GDP-Fuc:Galβ4Glc β1,2 fucosyltransferase | NM_018876.3 |

| β3GNT2 | 0.53 | UDP-GlcNAc:βGal β1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2 | NM_016888.4 |

| GM2A | 0.59 | GM2 ganglioside activator protein | NM_010299.2 |

| NAGA | 0.60 | N-Acetylgalactosaminidase α | NM_008669.3 |

| NEU1 | 0.61 | Neuraminidase 1 | NM_010893.2 |

| β3GALT4 | 0.64 | UDP-Gal:β-GalNAc β1,3-galactosyltransferase 4 (GM1/GD1b/Gg4 synthase) | NM_019420.2 |

| Up-regulated after TGF-β treatment | |||

| ST8SIA2 | 8.61 | CMP-NeuAc:N-acetylgalactosaminide α2,8-sialyltransferase 2 | NM_009181.2 |

| ST6GALNAC4 | 4.42 | CMP-NeuAC:β-N-acetylgalactosaminide α2,6-sialyltransferase 4 | NM_011373.2 |

| ST6GALNAC6 | 1.66 | CMP-NeuAC:β-N-acetylgalactosaminide α2,6-sialyltransferase 6 | NM_016973.2 |

| GALC | 1.60 | Galactocerebroside β-galactosidase | NM_008079.3 |

| GLA | 1.56 | α-Galactosidase A | NM_013463.2 |

| UGCG | 1.56 | UDP-glucose:N-acylsphingosine d-glucosyltransferase (GlcCer synthase) | NM_011673.3 |

| ST3GAL2 | 1.54 | CMP-NeuAc:β-galactoside α2,3-sialyltransferase 2 | NM_009179.3 |

| β4GALT2 | 1.46 | UDP-Gal:β-GlcNAc β1,4-galactosyltransferase 2 | NM_017377.4 |

Total RNA was extracted from control and TGF-β-treated cells as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed for gene expression using glycogene chip analysis (version GlycoV4) following the protocol of the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). The gene chip consists of 1246 mouse genes, including glycosyltransferases, carbohydrate-binding proteins, glycosylhydrolases, intercellular protein transport proteins, N-glycan biosynthesis-related proteins, and others (for details, see http://www.functionalglycomics.org). Among these genes, changes in expression level of the genes involved in metabolism of GSLs (mean value of triplicate RNA samples) are shown in this table.

Of the 24 genes listed in Table 1, 5 belong to the GSL degradation category, 1 is the activator of specific GalNAc-ase for GM2, and all others belong to the GSL synthesis category. Among these genes, only the decrease of the gene for β3Gal transferase-4 (β3GalT4; UDP-Gal:βGalNAcβ-1,3-galactosyltransferase-4; EC 2.4.1.62), which converts Gg3 to Gg4 in addition to synthesizing GM1 and GD1b (48) and whose expression showed a 0.64 fold change (TGF-β/control), with adjusted P = 0.00045, can explain the Gg4 reduction in TGF-β-treated cells.

Although the β3GalT4 gene is involved in the synthesis of both Gg4 and GM1, from Gg3 and GM2, respectively, only the level of Gg4, but not that of GM1 or GD1a, showed a clear decrease in TGF-β-treated NMuMG cells as reported previously (20). FucGM1 was absent in control and TGF-β-treated cells. These points were confirmed by binding with biotin-conjugated CTB for GM1 or HPTLC immunostaining with specific mAbs defining GD1a and FucGM1 (Fig. 1). The reason for the unchanged GM1 expression remains unclear (see Discussion). We observed that GM1 expression was also unchanged in hypoxia- or CoCl2-treated NMuMG cells (Supplemental Data), although Gg4 reduction was clearly observed in these cells, as described below.

Figure 1.

Ganglioside expression in control and TGF-β-treated NMuMG cells. A) Semiconfluent NMuMG cells in a culture dish (150 mm; Corning, Corning, NY, USA) were treated, and GSLs were extracted and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. An appropriate aliquot, based on the same amount of protein from the cell suspension, was spotted on an HPTLC plate together with standard GM1, GM2, GM3, Gg4, Gg3, GD1a, and FucGM1. After developing with chloroform/methanol/aqueous 0.2% CaCl2 (60:35:8), GSLs were visualized by spraying with orcinol/sulfuric acid (a) or immunostained with mAb TKH7 for Gg4 (b) or GD1a-1 for GD1a (d) and TKH5 for FucGM1 (e) or by affinity blot with CTB for GM1 (c), as described in Materials and Methods. Triplicate experiments gave similar results. B) Relative expression of Gg4, GM1, and GD1a in TGF-β-treated cells and control cells was calculated based on density analysis of HPTLC staining. Change in expression of each ganglioside is presented as mean ± sd percentage of the control value. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

EMT process induced by hypoxia and by CoCl2, which mimics hypoxia

Because many studies over the past few decades indicated that the EMT process is induced by hypoxia (for review, see refs. 10, 21), similar to that induced by TGF-β, we analyzed NMuMG cells cultured under hypoxia condition (∼1% O2) or treated with 100 μM CoCl2. Treatment with CoCl2 is known to mimic the hypoxia condition by inhibiting prolyl-4-hydroxylases involved in degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) (22, 49–51).

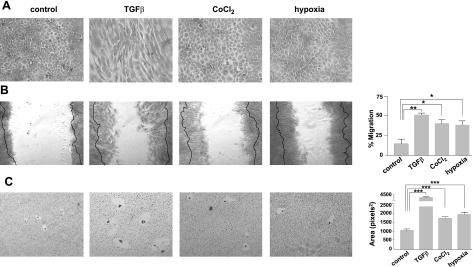

TGF-β-treated cells show fibroblastic morphology with clear cell elongation, as described previously (20) and confirmed in the present study. In contrast, cells treated with CoCl2 or hypoxia showed flattening compared with control cells (Fig. 2A). Flattened morphology could be associated with the EMT process, with less cohesive properties, as previously reported in human colorectal carcinoma cells, HRA-19 and Caco-2 (52).

Figure 2.

Effect of TGF-β, CoCl2, and hypoxia treatment on cell morphology and cell motility. A) For the cell morphology study, NMuMG cells were grown and treated as described in Materials and Methods, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde/PBS, stained with 1% toluidine blue, and photographed by phase-contrast microscopy. B) Cell motility was assessed by wound assay. Image panels: cell monolayers treated with TGF-β, CoCl2, and hypoxia were scratched with a 1- to 10-μl pipette tip at the marked position. Cells were washed with fresh serum-free medium twice and cultured in fresh culture medium. Pictures of the wounds were taken at 0 h and after an 8-h incubation under the normoxia condition at the marked position by Nikon phase-contrast microscopy (×80). Bold lines on each photo show the original edge of the scratched area at 0 h. Right panel: results are expressed as mean ± sd percentage area covered by moving cells after 8 h, analyzed using the Scion Image program. All experiments were performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. C) Cell motility was assessed by a phagokinetic cell motility assay. Image panels: NMuMG cells cultured and treated as above were detached with trypsin/EDTA, and 5 × 103 cells in complete culture medium were added onto each gold sol-coated well and incubated for 8 h under normoxia. Photos of track areas of 30 cells were taken; representative photos are presented. Right panel: cleared areas on gold sol were measured, analyzed using the Scion Image program as squared pixels, and are shown as means ± sd. Two independent experiments gave similar results. ***P < 0.001.

Cell motility was determined for hypoxia- or CoCl2-treated cells, because enhanced motility is a common characteristic acquired after the EMT process. Motility was strongly enhanced in CoCl2-, hypoxia-, and TGF-β-treated cells, compared with control cells, in both the wound assay (Fig. 2B) and phagokinetic assay (Fig. 2C). In both assay systems, particularly the phagokinetic assay, TGF-β treatment induced greater enhancement of cell motility than hypoxia or CoCl2 treatment.

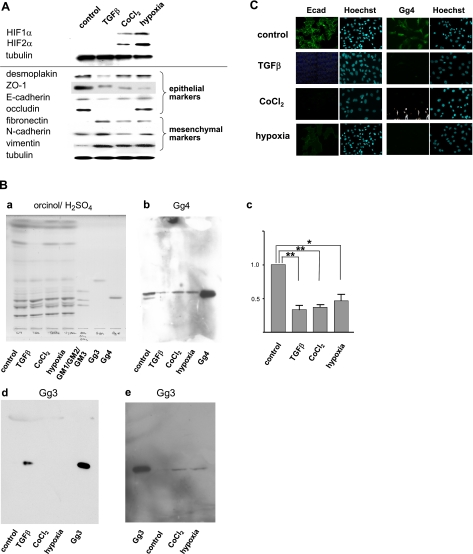

HIF-1α and HIF-2α, taken as indicators of the hypoxia condition, were strongly expressed in cells under both CoCl2 treatment and the hypoxia condition, whereas neither HIF was detected in control or TGF-β-treated cells (Fig. 3A, top). The EMT process induced under hypoxia was assessed by a reduction in epithelial cell marker proteins, concomitant with enhanced expression of mesenchymal cell marker proteins, cell morphology change, and enhanced cell motility. TGF-β-treated cells were analyzed together in all experiments and compared.

Figure 3.

Effect of TGF-β, CoCl2, and hypoxia on expression of epithelial vs. mesenchymal cell molecules, and expression of gangliosides. A) Cells were harvested, lysed in RIPA buffer, and subjected (10 μg protein/lane) to SDS-PAGE. For analysis of HIFs, which were not clearly detectable using RIPA lysates, cells were lysed with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. After the transferring and blocking procedure, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies and incubated with appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with HRP, and proteins were revealed with a SuperSignal chemiluminescence substrate kit (Thermo-Fisher/Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). After stripping with ReBlot Plus Mild Solution (Chemicon/Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), each membrane was reblotted with γ-tubulin as a loading control. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and representative Western blot results are shown. B) GSLs were extracted and analyzed by HPTLC as described in Materials and Methods. a) Orcinol/sulfuric acid spray. b) Gg4 detected with TKH7. c) Relative expression of Gg4 in control, TGF-β-, CoCl2-, or hypoxia-treated cells; presented as mean ± sd percentage of control value, as described for Fig. 1B. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; NS, not significant. d, e) Gg3 detected with 2D4. Notably, amounts of GSL spotted in e are 10 times higher than those in a, b, d. C) NMuMG cells (2×104) were seeded onto 12-mm-diameter glass cover slips in 24-well tissue culture plates; treated with TGF-β, CoCl2, or hypoxia as described in Materials and Methods; fixed with 2% fresh paraformaldehyde/PBS; blocked with 1% BSA/0.1% NaN3/PBS; and stained with anti-Ecad (left) or anti-Gg4 TKH7 (right), as described in Materials and Methods. Clear nuclei staining with Hoechst 44442 is shown next to each antibody staining.

Among the epithelial molecules analyzed, ZO-1 was clearly reduced in TGF-β-, CoCl2-, or hypoxia-treated cells; Ecad was significantly reduced in TGF-β- and CoCl2-treated cells; and occludin was greatly reduced and hardly detectable in TGF-β- and CoCl2-treated cells. Among the mesenchymal molecules, FN and vimentin were greatly enhanced in TGF-β-, CoCl2-, or hypoxia-treated cells, whereas the change in Ncad expression under CoCl2 or hypoxia, in comparison to that under TGF-β treatment, was not significant (Fig. 3A, bottom).

These results indicate that culturing under either the hypoxia condition or chemical hypoxia with CoCl2 induces the EMT process in NMuMG cells, comparable to that induced by TGF-β treatment.

Reduction of Gg4 expression in EMT process induced by hypoxia

Total GSL fractions were prepared from control NMuMG cells and from cells treated with TGF-β, CoCl2, or hypoxia and were analyzed for change in Gg4 expression by HPTLC immunostaining using anti-Gg4 mAb TKH7. Gg4 expression in CoCl2- or hypoxia-treated cells was significantly reduced to 36.6 ± 7.2 or 46.7 ± 16.7%, similarly to 33.0 ± 12.0% in TGF-β-treated cells, compared with that in control cells (Fig. 3Bb, c).

We also analyzed Gg3 expression in these cells using anti-Gg3 mAb 2D4, because Gg3 is the substrate of β3GalT4 and is expected to be accumulated when β3GalT4 is down-regulated. Gg3 was not detectable in control NMuMG cells but was clearly detected in TGF-β-treated cells (Fig. 3Bd). The Gg3 level was low in cells treated with CoCl2 or grown under hypoxia (Fig. 3Bd), and a large amount of GSL fraction was required to be placed on HPTLC for detection (Fig. 3Be). There are a few possible explanations for the difference in Gg3 accumulation, but the actual reason remains unknown.

The same GSL samples, separated on the same HPTLC plates, were stained with orcinol/sulfuric acid (Fig. 3Ba). Separation of the Gg4 band, slightly above standard GM2, was unclear, because total GSLs, not separated neutral GSLs, were analyzed. In contrast, a clear reduction in Gg4 was observed in TKH7 immunostaining of TGF-β-, CoCl2-, or hypoxia-treated cells (Fig. 3Bb, c).

In situ expression patterns of Gg4 and Ecad in NMuMG cells treated with CoCl2 or hypoxia

Analysis of in situ expression patterns confirmed the results from HPTLC immunostaining, i.e., a clear reduction in Gg4 expression in cells treated with TGF-β or CoCl2 or grown in hypoxia. The in situ staining of Ecad observed at the cell-cell interface in control cells was clearly reduced by treatment with TGF-β or CoCl2, whereas some cytoplasmic Ecad staining was detected in cells grown under hypoxia (Fig. 3C). The shift of Ecad to cytoplasm may explain the finding that cell motility is strongly enhanced, despite the small reduction of Ecad detected by Western blot, in hypoxia-treated cells.

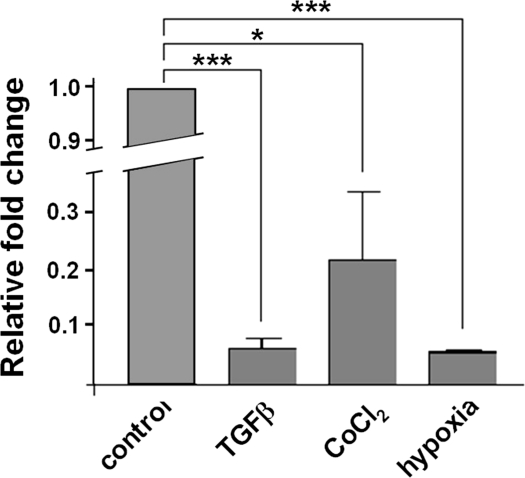

Down-regulation of β3GalT4 gene in EMT induced by TGF-β, CoCl2, or hypoxia

The expression level, assessed by RT-PCR analysis, of the β3GalT4 gene, which is responsible for Gg4 reduction induced by TGF-β treatment (Table 1), was down-regulated in treated cells. Quantitative real-time PCR results showed that relative expression (fold change) of the β3GalT4 gene in TGF-β-, CoCl2-, or hypoxia-treated cells was reduced to 0.0625 ± 0.0339, 0.2195 ± 0.2023, or 0.0562 ± 0.0030, compared with expression in nontreated cells (Fig. 4). Results from the glycogene chip array and quantitative real-time PCR showed the same direction, although the two experiments gave different fold changes, because of the different sensitivities. Reduction of β3GalT4 gene expression was in parallel with biochemical analysis of Gg4 expression as described above (Fig. 3). These results indicate that down-regulation of β3GalT4 gene expression is responsible for the Gg4 reduction observed in the EMT process caused by these inducers.

Figure 4.

Expression of the β3GalT4 gene in TGF-β-, CoCl2-, and hypoxia-treated cells. RNAs were prepared from control, TGFβ-, CoCl2-, or hypoxia-treated cells, as described in Materials and Methods. cDNA was prepared using SuperScript III First-Strand Super Mix and digested with DNase, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method as described previously (44) and represent fold change in gene expression relative to the nontreated control. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

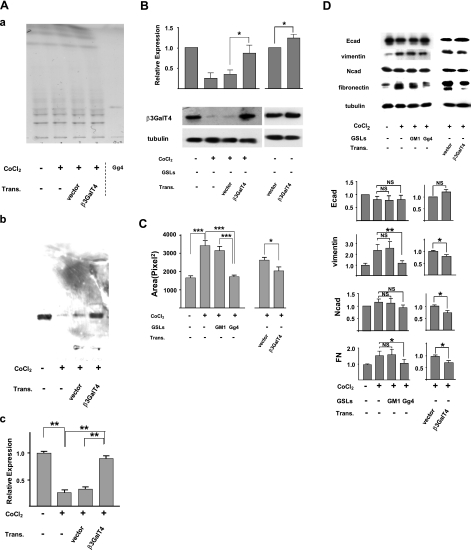

Effect of transfection of β3GalT4 gene and exogenous addition of Gg4 in EMT process induced by TGF-β, CoCl2, or hypoxia

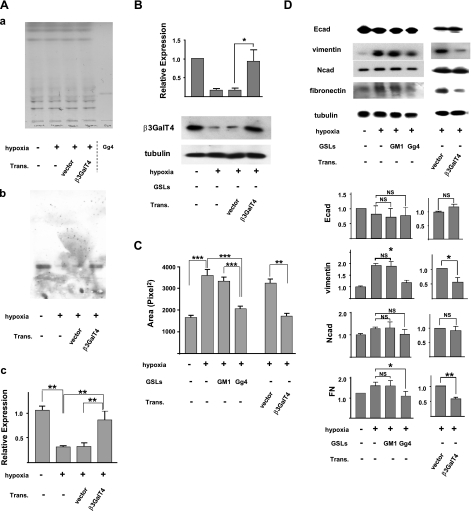

To determine whether Gg4 reduction is functionally involved in the EMT process, we examined the effect of β3GalT4 gene transfection on the EMT process induced by CoCl2. Mouse β3GalT4 gene constructed in expression vector or control empty vector was transfected into CoCl2-treated cells. Expression of Gg4 was strongly reduced in cells grown in the presence of CoCl2, and the reduced Gg4 level was restored to control cell level by transfection with constructed vector with β3GalT4 gene but not with empty vector (Fig. 5A, B). The EMT process was inhibited by transfection of the β3GalT4 gene but not of control vector; i.e., in cells treated with an EMT inducer followed by transfection of gene, compared with vector-transfected cells: cell motility was reduced (Fig. 5C), and expression of mesenchymal molecules vimentin and FN was significantly decreased, whereas expression of the epithelial molecule Ecad was essentially unchanged (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of CoCl2-induced EMT by overexpressed β3GalT4 or exogenous Gg4. To study the effect of ganglioside GM1 or Gg4 on the CoCl2-induced EMT process, cells were preincubated with 50 μM GM1 or Gg4 for 24 h and then were cultured in medium with 100 μM CoCl2 in the continued presence of 50 μM Gg4 or GM2 for 24 h. For study of the effect of overexpressed β3GalT4 on the CoCl2-induced EMT process, cells were treated with CoCl2 for 24 h and then were transfected with mouse β3GalT4 gene/pIRES-puro3 or vector only, as described in Materials and Methods. These cells were used for analysis of Gg4 and β3GalT4 expression, EMT marker molecules, and cell motility. Trans., transfection. A) For Gg4 analysis, cells (4×105/dish in a 6-cm dish) were treated with CoCl2 and transfected. GSLs were extracted and analyzed by HPTLC: a) orcinol/sulfuric acid spray; b) stained with TKH7 for Gg4. Experiments were performed in triplicate; representative HPTLC-immunostaining results are shown. c) Gg4 expression detected with TKH7 was calculated based on density analysis from 3 experiments; relative expression is shown as percentage of the control value. **P < 0.01. B) For β3GalT4 expression analysis, cells (5×104/well in a 12-well plate) were treated and transfected as described above. Cells were harvested, lysed in RIPA buffer, and subjected (10 μg of protein/slot) to SDS-PAGE. β3GalT4 expression in transfected cells was determined by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods. Experiments were performed in triplicate; representative Western blot results are shown (bottom). Normalized values with each loading control are shown as mean ± sd relative intensity on the ordinate (top). C) For the phagokinetic cell motility assay, NMuMG cells (5×104 cells/well in a 12-well plate) were treated as described above. Cells were detached with trypsin/EDTA, and 5 × 103 cells in complete culture medium were added onto each gold sol-coated well and incubated for 8 h, as described in Materials and Methods. Photos of track areas of 30 cells were taken. Cleared areas on gold sol were measured; values are means ± sd (squared pixels) from the Scion Image program. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. D) For EMT marker protein analysis, cells were treated, and SDS-PAGE and Western blot were performed as described above. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and representative Western blot results are shown (top). Normalized values with each loading control are shown as mean ± sd relative intensity on the ordinate (bottom). *P = 0.01–0.05; **P = 0.001–0.005; NS, not significant.

We also confirmed the inhibitory effect of exogenously added Gg4 on the CoCl2-induced EMT process, using a procedure similar to that used previously for TGF-β-induced EMT (20). Cells were preincubated with Gg4 or GM1 for 24 h, and the EMT process was then induced by CoCl2 in the presence of the GSL. The EMT process induced by CoCl2 was inhibited by Gg4, but not by GM1; i.e., in cells treated with Gg4 plus EMT inducer, compared with cells treated with GM1 plus EMT inducer or in cells treated with the EMT inducer alone: cell motility was reduced (Fig. 5C), and expression of mesenchymal molecules vimentin and FN was decreased (Fig. 5D).

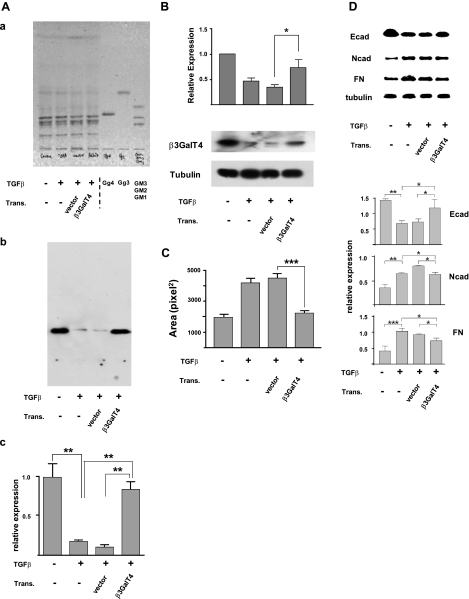

We then performed the same procedure as in Fig. 5, i.e., NMuMG cells were transfected with the β3GalT4 gene and preincubated with Gg4, except that in this case the EMT process was induced by hypoxia (∼1% O2) instead of by 100 μM CoCl2. Cells transfected with the β3GalT4 gene showed almost the same expression of Gg4 and enzyme β3GalT4 as nontreated cells, whereas cells transfected with control vector showed low expression of Gg4 and enzyme β3GalT4 similar to that in hypoxia-treated cells (Fig. 6A, B). Characteristics of inhibited EMT, i.e., reduced cell motility (Fig. 6C), and decreased expression of vimentin and FN (Fig. 6D), were observed in NMuMG cells that were transfected with β3GalT4 and treated with hypoxia. Next, we confirmed that exogenous addition of Gg4 causes functional inhibition of the hypoxia-induced EMT process, i.e., inhibition of cell motility (Fig. 6C), and decreased expression of vimentin and FN (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of hypoxia-induced EMT by overexpressed β3GalT4 or exogenous Gg4. Cells were grown and treated with the hypoxia condition as described in Materials and Methods. GM1 or Gg4 was added, and transfection procedures were performed as described for Fig. 5. Expression of Gg4 (A) and β3GalT4 (B) in transfected cells, cell motility (C), and expression of EMT marker protein (D) affected by overexpressed β3GalT4 or exogenous Gg4 are shown as described for Fig. 5. Trans., transfection. *P = 0.01–0.05; **P = 0.001–0.005; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Based on our previous observation that exogenous addition of Gg4 inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT (20), we performed the transfection procedure as above in TGF-β-treated cells. Expression of Gg4 and its synthase in β3GalT4-transfected cells was restored to the same levels as those in nontreated cells (Fig. 7A, B). β3GalT4-transfected cells also showed clear inhibition of the EMT process; i.e., cell motility was reduced (Fig. 7C), expression of mesenchymal molecules FN and Ncad was decreased, and expression of epithelial molecule Ecad was increased (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of TGF-β-induced EMT by overexpressed β3GalT4. Cells were cultured in culture medium overnight; then medium was replaced with fresh medium alone (control) or with fresh medium containing 1 ng/ml TGF-β for 18 h. Transfection was performed as described in Materials and Methods and for Fig. 5. Cells were analyzed for Gg4 expression (A), β3GalT4 expression (B), cell motility (C), and EMT marker molecules (D), as described for Fig. 5. Trans., transfection. A) For Gg4 analysis, cells (4×105/dish in a 6-cm dish) were treated with TGF-β and transfected. GSLs were extracted, and analyzed by HPTLC: a) orcinol/sulfuric acid spray; b) stained with TKH7 for Gg4. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and representative HPTLC immunostaining results are shown. c) Gg4 expression detected with TKH7 was calculated based on density analysis from 3 experiments and is shown as relative expression, as described for Fig. 5. **P < 0.01. B) For β3GalT4 expression analysis, cells (5×104/well in a 12-well plate) were treated and transfected as described above. Cells were harvested, lysed in RIPA buffer, and subjected (10 μg of protein/slot) to SDS-PAGE. β3GalT4 expression in transfected cells was determined by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods. Experiments were performed in triplicate; representative Western blot results are shown (bottom). Normalized values with each loading control are shown as mean ± sd relative intensity on the ordinate (top). *P = 0.01–0.05. C) NMuMG cells were treated as described above. Phagokinetic cell motility assay was performed as described for Fig. 5. Values are means ± sd (squared pixels) from Scion Image. ***P < 0.001. D) For EMT marker protein analysis, cells were treated as described above. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Representative Western blot results are shown (top); normalized values with each loading control are shown as mean ± sd relative intensity on the ordinate (bottom). *P = 0.01–0.05; **P = 0.001–0.005; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Taken together, the present results validate our previous findings (20) and indicate that Gg4 reduction plays a key functional role in the EMT process of NMuMG cells.

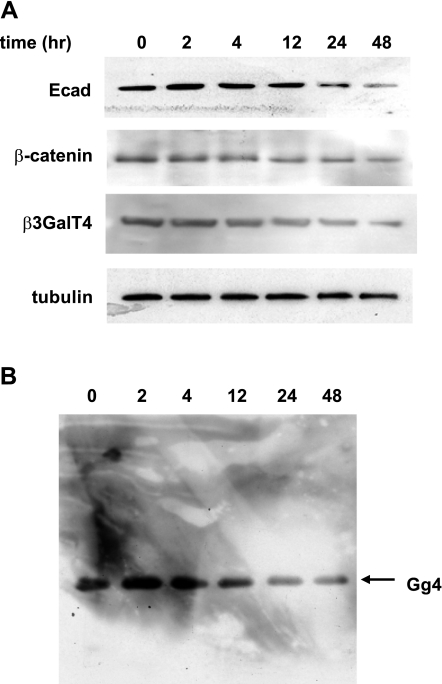

Gg4 is associated with Ecad and β-catenin

Because our results indicate that Gg4 functions to inhibit EMT induction and to maintain epithelial cell status and Ecad is known to be important in maintaining epithelial cell-cell tight interaction, we examined the time course changes in Ecad, β-catenin, and β3GalT4 protein compared with that for Gg4 in the GSL fraction immunoblotted by TKH7 during the TGF-β-induced EMT process. Reductions in all four molecules were detected during 12–24 h (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Expression of Ecad, β-catenin, β3GalT4, and Gg4 at various times after TGF-β treatment. Cells were treated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for various periods of time as indicated. A) Cells were harvested, and cell lysates prepared using RIPA buffer were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against Ecad, β-catenin, β3GalT4, or γ-tubulin. B) Cells treated as above were harvested and extracted with isopropanol/hexane/water (55:25:20) for Gg4 detection with mAb TKH7. as described in Materials and Methods.

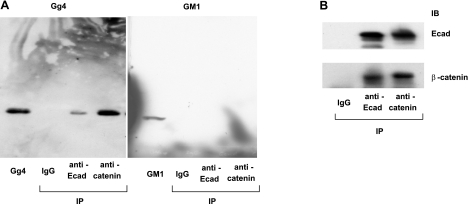

The finding of similar time-course changes for these four molecules suggested that they may be functionally associated. We therefore investigated a possible interaction of Gg4 with Ecad and other epithelial markers. PNF prepared with Brij 98 lysis buffer was immunoprecipitated with anti-Ecad or anti-β-catenin antibodies, and Gg4 content in the immunoprecipitates was analyzed. Gg4 was detected in both immunoprecipitates, although that with anti-β-catenin antibody contained more Gg4 than that with anti-Ecad antibody (Fig. 9A, left). Neither precipitate showed a detectable amount of GM1 (Fig. 9A, right), which is not down-regulated during the EMT process and has no regulatory effect on EMT. The interaction between Ecad and β-catenin is known to be crucial for establishment of epithelial cell polarity (53, 54). Indeed, Ecad and β-catenin in NMuMG cells showed interaction by immunoprecipitation, whereas mouse IgG did not show any detectable band, as was predicted (Fig. 9B). These results support our hypothesis that Gg4 modulates the EMT process through its interaction with key epithelial cell molecules on the cell surface.

Figure 9.

Interaction of Gg4 with the Ecad/β-catenin complex. PNF prepared from NMuMG cells was precleared with protein A/G agarose beads and incubated with protein A/G agarose beads prebound with control mouse IgG, anti-Ecad, or anti-β-catenin antibody at 4°C for 3 h, as described in Materials and Methods, and subjected to HPTLC and Western blot analysis as described below. A) For HPTLC analysis, the mixture was washed 5 times with washing buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate and 150 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.2), and GSLs were extracted with isopropanol/hexane/water (55:25:20). After hydrolysis of glycerophospholipids in 0.1 M NaOH in methanol at 40°C for 2 h and neutralization with 1 N HCl, extracts were evaporated, desalted with a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge, and dried under a nitrogen stream. The GSL preparation was dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1). An amount equivalent to 500 μg of protein of starting PNF, together with standard Gg4 or GM1 as control, was applied to HPTLC and detected with mAb TKH7 (left) or CTB (right). B) For Western blot analysis, the mixture was washed 5 times with washing buffer and boiled for 10 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and an amount equivalent to 10 μg of starting PNF was subjected to SDS-PAGE. After the transferring and blocking procedure, membranes were incubated with anti-Ecad or anti-β-catenin antibodies and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate, and proteins were revealed with a SuperSignal chemiluminescence substrate kit. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting.

In view of our previous finding that exogenous addition of Gg4 inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT (20) and our present results from analysis of the EMT process induced by 3 different treatments (hypoxia, chemical hypoxia, and TGF-β) and Gg4 complexed with Ecad/β-catenin, we propose that Gg4 plays a crucial role in epithelial cell-cell adhesion through stabilization of Ecad and catenin, possibly through their complex.

DISCUSSION

The concept of the EMT process is based on changes in morphology and in responses of cell surface components and the cytoskeleton, when cells come in contact with extracellular matrix molecules (1–4). These studies were initiated by Hay and colleagues, based mainly on the phenotypic change of epithelial cells in tissue, rather than separated cell culture (for review, see ref. 1). Subsequent studies by many other groups, with various types of cells and cell lines in vitro, led to the concept that the EMT process provides a basis for phenotypic changes in embryogenesis (1, 9) and in disease development, including cancer progression (for review, see refs. 5, 6, 15). However, the possibility arises that an “EMT-like” phenotypic change with cell lines may not reflect the original observations with primary cells in tissues (1–4). Glycosylation changes associated with EMT may be caused by an in vitro effect, observed only in cell lines. Despite this possibility, all cells express glycosylation, and phenotypic changes of cells are closely associated with glycosylation changes. In fact, the preimplantation embryo expresses Lewis X (Lex) glycan, whose expression in vivo is greatly enhanced in the morula-stage embryo and declines quickly. This Lex glycan itself inhibited the compaction process of embryos (55). GM3 expression of primary chicken fibroblasts was greatly decreased on oncogenic transformation by Rous sarcoma virus (56), and transformed phenotype reverted to that of normal fibroblasts by a temperature-sensitive mutant of the Rous sarcoma virus (57). All of these findings indicate that glycosylation may be closely associated with phenotypic status.

Our previous study on altered expression of GSLs associated with the EMT process induced by TGF-β demonstrated reduced expression of Gg4 or GM2 in mouse and human epithelial cells, whereby expression of epithelial molecules declined and that of mesenchymal molecules increased, with enhanced cell motility and morphology change (20). Such phenotypic changes were also observed in cells treated with d-threo-1-ethylendioxyphenyl-2-palmitoylamino-3-pyrrolidino-propanol, which blocks synthesis of all GSLs derived from glucosylceramide (58), suggesting that some GSLs are involved in modulation of the EMT process in these cells (20). The following points in this previous study, however, remained to be clarified and are addressed in the present study.

First, to determine whether GSL changes, particularly reduction in Gg4, are observed only in the TGF-β-induced EMT process, we examined the effects of the hypoxia condition, which is also known to induce the EMT process (for review, see refs. 10, 21). Two methods were used to induce the hypoxia condition in NMuMG cells: culturing cells under hypoxia (∼1% O2) (10, 21) or culturing cells under normoxia (∼21% O2) in the presence of a chemical mimetic of hypoxia, CoCl2 (22, 49–51). In either condition, EMT was induced in NMuMG cells, as assessed by the reduction in epithelial marker molecules, enhancement of mesenchymal molecules, and enhancement of cell motility. The Gg4 expression level was reduced in these hypoxia-treated cells similarly to the reduction in TGF-β-treated cells, indicating that Gg4 reduction has a connection with the EMT process rather than with TGF-β.

Second, GSL expression changes are regulated by various mechanisms, including not only glycosyltransferases but also glycosidases, sugar nucleotide transporters, and others (18, 19). We therefore analyzed mRNA expression of genes potentially responsible for Gg4 reduction in the EMT process, using a glycogene chip array followed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Our results revealed that the mRNA level of the β3GalT4 gene, which is responsible for synthesis of Gg4 from Gg3, was reduced in both the TGF-β-induced and hypoxia-induced EMT process. Results with HPTLC immunostaining showed a reduction in Gg4, but no changes in any other GSL or ganglioside (e.g., GM1, GD1a, and FucGM1). The reason that expression of GM1, which is reported to also be synthesized by the β3GalT4 gene (48), showed no change in the EMT process of NMuMG cells remains to be clarified. Perhaps some organizational difference of acceptor GSLs in Golgi may explain the differential response of Gg4 vs. GM1 (59–61). The mechanism underlying down-regulation of the β3GalT4 gene in the EMT process also remains to be studied.

Third, to clarify the functional role of Gg4 reduction in EMT process, two different approaches were used: preincubation with Gg4 or transfection of the β3GalT4 gene, in TGF-β- or hypoxia-treated NMuMG cells. Both showed a clear inhibitory effect on TGF-β- or hypoxia-induced EMT. Taken together with our previous finding that the TGF-β-induced EMT process is blocked by preincubation of cells with Gg4 (20), this finding confirms the functional role of Gg4 reduction in EMT. We further determined that Gg4 has a strong binding capacity with Ecad and β-catenin, perhaps through their complex, which may be a functional unit mediating cell-cell adhesion.

In recent decades, many studies have indicated that hypoxic microenvironments (∼1% O2) surrounding solid tumors in cancer patients contribute greatly to cancer progression, mostly through hypoxia-induced EMT processes (for review, see refs. 10, 21), which often cooperate with various signaling mechanisms such as those mediated by the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (23–25), Notch signaling (26), or cMet (27). A few studies have addressed the effect of hypoxia on enhanced expression of functionally well-defined cellular glycosylation (62, 63), although the possible correlation of GSL changes with the EMT process was not addressed. Our findings suggest possible involvement of GSLs in cancer progression through modulation of the EMT process.

Results of the present study clearly indicate that the EMT process is closely correlated with expression of Gg4 and the β3GalT4 gene, and the process is blocked by exogenous addition of Gg4 or transfection of the β3GalT4 gene. Based on these results, we hypothesize that a high level of Gg4 is required for maintenance of Ecad-mediated epithelial cell-to-cell adhesion, possibly at junction points; reduction/depletion of Gg4 (due to decreased expression or loss of the β3GalT4 gene) causes instability of the Ecad/β-catenin/Gg4 complex; this causes loss of the complex at junction points, and Ecad disappears through partial degradation with endocytosis; which may lead to enhanced expression of mesenchymal molecules and associated enhancement of motility. The initial event of the entire series of changes associated with the EMT process is reduction of Gg4.

Throughout this study, Gg4 synthesis was clearly found to be down-regulated, whereas synthesis of GM1 and GM1-derived gangliosides was unchanged during the EMT process in NMuMG cells. The ability of ganglioside synthesis in Golgi depends not only on the presence of specific glycosyltransferases, sugar nucleotides, and acceptor GSLs but also on their assembly and organization at different sites of the Golgi membrane. The first factor can be readily analyzed, but the second factor is highly variable, depending on growth and environmental conditions, and is difficult to assess (61, 64). In addition, major GSL synthetic pathways in Golgi may be defined by yet unidentified factors (59). Thus, unambiguous demonstration of the effect of GSL changes on the EMT process may require extensive further studies of each glycosylation process associated with EMT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ronald L. Schnaar (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA) for the kind donation of GD1a-1 and anti-GD1a antibody, Levi Lowder for construction of the expression vector, and Steve Anderson for assistance with preparation of the manuscript and figures.

This work was funded primarily by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute (grant 2R01-CA080054 to S.H.) and in part by the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant GM62116 to the Consortium for Functional Glycomics).

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hay E. D. (2005) The mesenchymal cell, its role in the embryo, and the remarkable signaling mechanisms that create it. Dev. Dyn. 233, 706–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugrue S. P., Hay E. D. (1981) Response of basal epithelial cell surface and cytoskeleton to solubilized extracellular matrix molecules. J. Cell Biol. 91, 45–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugrue S. P., Hay E. D. (1982) Interaction of embryonic corneal epithelium with exogenous collagen, laminin, and fibronectin: role of endogenous protein synthesis. Dev. Biol. 92, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugrue S. P., Hay E. D. (1986) The identification of extracellular matrix (ECM) binding sites on the basal surface of embryonic corneal epithelium and the effect of ECM binding on epithelial collagen production. J. Cell Biol. 102, 1907–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J. M., Dedhar S., Kalluri R., Thompson E. W. (2006) The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J. Cell Biol. 172, 973–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L., Neaves W. B. (2006) Normal stem cells and cancer stem cells: the niche matters. Cancer Res. 66, 4553–4557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim K. K., Kugler M. C., Wolters P. J., Robillard L., Galvez M. G., Brumwell A. N., Sheppard D., Chapman H. A. (2006) Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 13180–13185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeisberg E. M., Tarnavski O., Zeisberg M., Dorfman A. L., McMullen J. R., Gustafsson E., Chandraker A., Yuan X., Pu W. T., Roberts A. B., Neilson E. G., Sayegh M. H., Izumo S., Kalluri R. (2007) Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat. Med. 13, 952–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiery J. P., Acloque H., Huang R. J. Y., Nieto M. A. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139, 871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haase V. H. (2009) Oxygen regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: insights into molecular mechanisms and relevance to disease. Kidney Int. 76, 492–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono M., Handa K., Sonnino S., Withers D. A., Nagai H., Hakomori S. (2001) GM3 ganglioside inhibits CD9-facilitated haptotactic cell motility: co-expression of GM3 and CD9 is essential in down-regulation of tumor cell motility and malignancy. Biochemistry 40, 6414–6421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakami Y., Kawakami K., Steelant W. F. A., Ono M., Baek R. C., Handa K., Withers D. A., Hakomori S. (2002) Tetraspanin CD9 is a “proteolipid,” and its interaction with α3 integrin in microdomain is promoted by GM3 ganglioside, leading to inhibition of laminin-5-dependent cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34349–34358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsuzuka K., Handa K., Satoh M., Arai Y., Hakomori S. (2005) A specific microdomain (“glycosynapse 3”) controls phenotypic conversion and reversion of bladder cancer cells through GM3-mediated interaction of alpha3beta1 integrin with CD9. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35545–35553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prinetti A., Aureli M., Illuzzi G., Prioni S., Nocco V., Scandroglio F., Gagliano N., Tredici G., Rodriguez-Menendez V., Chigorno V., Sonnino S. (2010) GM3 synthase overexpression results in reduced cell motility and in caveolin-1 up-regulation in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Glycobiology 20, 62–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turley E. A., Veiseh M., Radisky D. C., Bissell M. J. (2008) Mechanisms of disease: epithelial-mesenchymal transition—does cellular plasticity fuel neoplastic progression? Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 5, 280–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larue L., Bellacosa A. (2005) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene 24, 7443–7454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakomori S. (2000) Traveling for the glycosphingolipid path. Glycoconj. J. 17, 627–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakomori S. (2002) Glycosylation defining cancer malignancy: new wine in an old bottle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 10231–10233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bektas M., Spiegel S. (2004) Glycosphingolipids and cell death. Glycoconj. J. 20, 39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan F., Handa K., Hakomori S. (2009) Specific glycosphingolipids mediate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of human and mouse epithelial cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 7461–7466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klymkowsky M. W., Savagner P. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: a cancer researcher's conceptual friend and foe. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 1588–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G. L., Jiang B. H., Rue E. A., Semenza G. L. (1995) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92, 5510–5514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lester R. D., Jo M., Montel V., Takimoto S., Gonias S. L. (2007) uPAR induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hypoxic breast cancer cells. J. Cell Biol. 178, 425–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham C. H., Forsdike J., Fitzgerald C. J., Macdonald-Goodfellow S. (1999) Hypoxia-mediated stimulation of carcinoma cell invasiveness via upregulation of urokinase receptor expression. Int. J. Cancer 80, 617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rofstad E. K., Rasmussen H., Galappathi K., Mathiesen B., Nilsen K., Graff B. A. (2002) Hypoxia promotes lymph node metastasis in human melanoma xenografts by up-regulating the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor. Cancer Res. 62, 1847–1853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahlgren C., Gustafsson M. V., Jin S., Poellinger L., Lendahl U. (2008) Notch signaling mediates hypoxia-induced tumor cell migration and invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 6392–6397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pennacchietti S., Michieli P., Galluzzo M., Mazzone M., Giordano S., Comoglio P. M. (2003) Hypoxia promotes invasive growth by transcriptional activation of the met protooncogene. Cancer Cell 3, 347–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zavadil J., Bottinger E. P. (2005) TGF-β and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene 24, 5764–5774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen J.-E. S., Clausen H., Nielsen C., Teglbjaerg L. S., Hansen L. L., Nielsen C. M., Dabelsteen E., Mathiesen L., Hakomori S., Nielsen J. O. (1990) Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in vitro by anticarbohydrate monoclonal antibodies: Peripheral glycosylation of HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 may be a target for virus neutralization. J. Virol. 64, 2833–2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vangsted A. J., Clausen H., Kjeldsen T. B., White T., Sweeney B., Hakomori S., Drivsholm L., Zeuthen J. (1991) Immunochemical detection of a small cell lung cancer-associated ganglioside (FucGM1) in serum. Cancer Res. 51, 2879–2884 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young W. W., MacDonald E. M. S., Nowinski R. C., Hakomori S. (1979) Production of monoclonal antibodies specific for distinct portions of the glycolipid asialo GM2 (gangliotriosylceramide). J. Exp. Med. 150, 1008–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez P. H., Zhang G., Bianchet M. A., Schnaar R. L., Sheikh K. A. (2008) Structural requirements of anti-GD1a antibodies determine their target specificity. Brain 131, 1926–1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockhart D. J., Dong H., Byrne M. C., Follettie M. T., Gallo M. V., Chee M. S., Mittmann M., Wang C., Kobayashi M., Horton H., Brown E. L. (1996) Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 1675–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolstad B. M., Irizarry R. A., Astrand M., Speed T. P. (2003) A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19, 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irizarry R. A., Bolstad B. M., Collin F., Cope L. M., Hobbs B., Speed T. P. (2003) Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smyth G. K. (2004) Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3(1), Article 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smyth G. K. (2005) Limma: linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor (Gentleman R., Carrey V., Dudoit S., Irizarry R., Huber W. eds) pp. 397–420, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toledo M. S., Suzuki E., Handa K., Hakomori S. (2005) Effect of ganglioside and tetraspanins in microdomains on interaction of integrins with fibroblast growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16227–16234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todeschini A. R., Dos Santos J. N., Handa K., Hakomori S. (2007) Ganglioside GM2-tetraspanin CD82 complex inhibits Met and its cross-talk with integrins, providing a basis for control of cell motility through glycosynapse. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8123–8133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Todeschini A. R., Dos Santos J. N., Handa K., Hakomori S. (2008) Ganglioside GM2/GM3 complex affixed on silica nanospheres strongly inhibits cell motility through CD82/cMet-mediated pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 1925–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Straus A. H., Carter W. G., Wayner E. A., Hakomori S. (1989) Mechanism of fibronectin-mediated cell migration: dependence or independence of cell migration susceptibility on RGDS-directed receptor (integrin). Exp. Cell Res. 183, 126–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodman S. L., Vollmers H. P., Birchmeier W. (1985) Control of cell locomotion: perturbation with an antibody directed against specific glycoproteins. Cell 41, 1029–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodgers W., Rose J. K. (1996) Exclusion of CD45 inhibits activity of p56lck associated with glycolipid-enriched membrane domains. J. Cell Biol. 135, 1515–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamura S., Handa K., Hakomori S. (1997) A close association of GM3 with c-Src and Rho in GM3-enriched microdomains at the B16 melanoma cell surface membrane: a preliminary note. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 236, 218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwabuchi K., Yamamura S., Prinetti A., Handa K., Hakomori S. (1998) GM3-enriched microdomain involved in cell adhesion and signal transduction through carbohydrate-carbohydrate interaction in mouse melanoma B16 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9130–9138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyazaki H., Fukumoto S., Okada M., Hasegawa T., Furukawa K., Furukawa K. (1997) Expression cloning of rat cDNA encoding UDP-galactose:GD2 β1,3-galactosyltransferase that determines the expression of GD1b/GM1/GA1. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24794–24799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan Y., Hilliard G., Ferguson T., Millhorn D. E. (2003) Cobalt inhibits the interaction between hypoxia-inducible factor-α and von Hippel-Lindau protein by direct binding to hypoxia-inducible factor-α. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15911–15916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chachami G., Simos G., Hatziefthimiou A., Bonanou S., Molyvdas P. A., Paraskeva E. (2004) Cobalt induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in airway smooth muscle cells by a reactive oxygen species- and PI3K-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 31, 544–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vengellur A., LaPres J. J. (2004) The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1α in cobalt chloride induced cell death in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Toxicol. Sci. 82, 638–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirkland S. C. (2009) Type I collagen inhibits differentiation and promotes a stem cell-like phenotype in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Br. J. Cancer 101, 320–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aberle H., Schwartz H., Kemler R. (1996) Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J. Cell. Biochem. 61, 514–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nathke I. S., Hinck L., Swedlow J. R., Papkoff J., Nelson W. J. (1994) Defining interactions and distributions of cadherin and catenin complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 125, 1341–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fenderson B. A., Zehavi U., Hakomori S. (1984) A multivalent lacto-N-fucopentaose III-lysyllysine conjugate decompacts preimplantation mouse embryos, while the free oligosaccharide is ineffective. J. Exp. Med. 160, 1591–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hakomori S., Saito T., Vogt P. K. (1971) Transformation by Rous sarcoma virus: effects on cellular glycolipids. Virology 44, 609–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hakomori S., Wyke J. A., Vogt P. K. (1977) Glycolipids of chick embryo fibroblasts infected with temperature-sensitive mutants of avian sarcoma viruses. Virology 76, 485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee L., Abe A., Shayman J. A. (1999) Improved inhibitors of glucosylceramide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14662–14669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Young W. W. J., Lutz M. S., Mills S. E., Lechler-Osborn S. (1990) Use of brefeldin A to define sites of glycosphingolipid synthesis: GA2/GM2/GD2 synthase is trans to the brefeldin A block. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87, 6838–6842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maxzud M. K., Daniotti J. L., Maccioni H. J. (1995) Functional coupling of glycosyl transfer steps for synthesis of gangliosides in Golgi membranes from neural retina cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20207–20214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giraudo C. G., Daniotti J. L., Maccioni H. J. (2001) Physical and functional association of glycolipid N-acetyl-galactosaminyl and galactosyl transferases in the Golgi apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 1625–1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin J., Hashimoto A., Izawa M., Miyazaki K., Chen G. Y., Takematsu H., Kozutsumi Y., Suzuki A., Furuhata K., Cheng F. L., Lin C. H., Sato C., Kitajima K., Kannagi R. (2006) Hypoxic culture induces expression of sialin, a sialic acid transporter, and cancer-associated gangliosides containing non-human sialic acid on human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 66, 2937–2945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koike T., Kimura N., Miyazaki K., Yabuta T., Kumamoto K., Takenoshita S., Chen J., Kobayashi M., Hosokawa M., Taniguchi A., Kojima T., Ishida N., Kawakita M., Yamamoto H., Takematsu H., Suzuki A., Kozutsumi Y., Kannagi R. (2004) Hypoxia induces adhesion molecules on cancer cells: a missing link between Warburg effect and induction of selectin-ligand carbohydrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 8132–8137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uliana A. S., Giraudo C. G., Maccioni H. J. (2006) Cytoplasmic tails of SialT2 and GalNAcT impose their respective proximal and distal Golgi localization. Traffic 7, 604–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.