Abstract

Many specifically human psychiatric and neurological conditions have developmental origins. Rodent models are extremely valuable for the investigation of brain development, but cannot provide insight into aspects that are specifically human. The human brain, and particularly the cerebral cortex, has some unique genetic, molecular, cellular and anatomical features, and these need to be further explored. Cortical expansion in human is not just quantitative; there are some novel types of neurons and cytoarchitectonic areas identified by their gene expression, connectivity and functions that do not exist in rodents. Recent research into human brain development has revealed more elaborated neurogenetic compartments, radial and tangential migration, transient cell layers in the subplate, and a greater diversity of early-generated neurons, including predecessor neurons. Recently there has been a renaissance of the study of human brain development because of these unique differences, made possible by the availability of new techniques. This review gives a flavour of the recent studies stemming from this renewed focus on the developing human brain.

Keywords: development, embryonic gene expression, human cerebral cortex, interstitial neurons, magnetic resonance imaging, neurogenesis, neuronal migration, plasticity, prenatal and perinatal brain lesions, regeneration, subplate

Introduction

The initial discoveries of the basic cellular events and fundamental principles of the development of the vertebrate central nervous system came from the classical histological studies of postmortem human embryonic and fetal brains at the turn of the 19th/20th century (e.g. His, 1904; Hochstetter, 1919). Although even today most neuroscientists carry out research with the implicit intention of providing insight into the development and workings of our own brain and the hope of finding ways to treat human neurological and neuro-psychiatric diseases, by necessity the vast majority of studies are carried out on animal models. The reasons for this are obvious: one simply cannot contemplate employing invasive techniques such as intracellular recording, tract tracing, experimental anatomical manipulations or in-vivo microdialysis and gene manipulations in humans. Even where non-invasive techniques have been developed, e.g. functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography scanning, they have considerable limitations and are not easily adapted for babies, or for in-utero examination. As a result, our understanding of the mechanisms of cellular and pathological brain development depends almost exclusively on information obtained from animal models.

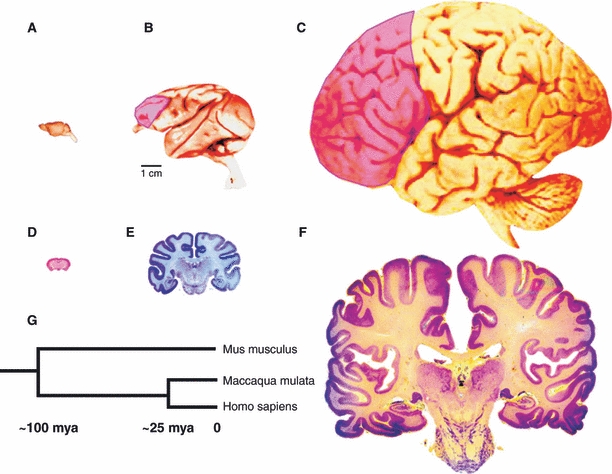

Enormous progress has been made by animal-based research, but it is imperative to study, in addition, the development of the brain directly on human tissue for several powerful reasons. First, the human brain, and particularly cerebral cortex, has some unique genetic, molecular, cellular and anatomical features. Second, many specifically human psychiatric and neurological conditions have developmental origins. Third, it is very difficult to interpret and extrapolate with certainty the data obtained in rodents to understand aspects of human brain development including evolutionarily novel traits. Fourth, it has been realized that cortical expansion in primates is not just quantitative and that there are some novel types of neurons and cytoarchitectonic areas identified by their gene expression, connectivity and functions that do not exist in rodents (Fig. 1). Advances in molecular genetics and stem cell biology that enable the study of gene expression and the activity of transcription factors directly on the tissue and cells of interest have facilitated direct investigation of the developing human brain. Furthermore, techniques for non-invasively studying the immature human brain are improving rapidly in both sophistication and resolution, allowing observations that were not even contemplated a few years ago.

Fig. 1.

Cerebral hemispheres of the mouse (A), macaque monkey (B) and human (C) drawn at approximately the same scale to convey the overall difference in the size and elaboration of the cerebral cortex. The pink overlay indicates the area of the prefrontal cortex that has no counterpart in mouse. The coronal sections of the cerebral hemispheres of the same species (D–F) illustrate the relatively small increase in the thickness of the neocortex compared with a large difference in surface of approximately 1 : 100 : 1000 in mouse, macaque monkey and human, respectively. (G) The time-scale of phylogenetic divergence of Mus musculus, Maccaca mulata and Homo sapiens based on the DNA sequencing data. Modified from Rakic (2009). Original panels are from the Comparative Mammalian Brain Collection: http://www.mirrorservice.org/sites/brainmuseum.org/index.html.

Recent progress in our understanding of human cortical development

In spite of all the obstacles and difficulties, there have been considerable advances in our knowledge of the basic pattern of human cortical development since the Committee of the American Associations of Anatomists met in Boulder, Colorado in 1970 to propose a unified nomenclature for vertebrate brain development based on the human fetal cerebrum (Boulder Committee, 1970; reviewed in Bystron et al. 2008). New proliferative and transient cellular compartments in the developing cerebrum have been described and characterized. Furthermore, our understanding of cortical regionalization into cytoarchitectonic fields has increased dramatically. For instance, the mechanisms leading to cortical arealization and its elaboration during evolution have been extensively studied. This is an important conceptual and biomedical issue, as it addresses the question of how the human cerebral cortex has acquired some cognitive functions such as abstract thinking and language.

Principles of cortical arealization in human

The protomap hypothesis, originally proposed by Rakic (1988), states that the proliferative ventricular zone of the forebrain, by virtue of differential patterns of gene expression, maps out the prospective areal, laminar and columnar organization of the cerebral cortex. According to this hypothesis, postmitotic neurons at their birth close to the cerebral ventricle potentially contain the genetic instructions essential for finding their final place of residence in the cortex, where they form a basic species-specific pattern of subcortical and cortico-cortical connection. Although these connections can be refined by spontaneous and extrinsic activity after their formation and modified in response to injury, they are remarkably stereotyped in each species (Brodmann, 1908; Rakic et al. 1991, 2009). This concept stands in opposition to the protocortex hypothesis that states that all cortical neurons, at least at the onset of cortical development, have the same potential, and that their cell fate is driven entirely by external forces such as the inputs from the specific thalamic nuclei (O’Leary, 1989). In the past two decades the results of many studies, including some from the initial proponents of the protocortex hypothesis, have increasingly supported the validity of the protomap model. For example, patterning centres in the developing forebrain that secrete diffusible morphogenetic proteins such as fibroblast growth factors, Wnts, sonic hedgehog or bone morphogenetic proteins create gradients that can control gene expression even before the formation of connections (Fukuchi-Shimogori & Grove, 2003; Cholfin & Rubenstein, 2007; O’Leary & Borngasser, 2006; O’Leary & Sahara, 2008). Even the final position and phenotype of GABAergic interneurons, which were traditionally considered to be randomly dispersed, appear to be determined at the time of their last cell division in the specific segments of the ganglionic eminence (Merkle et al. 2007; Batista-Brito et al. 2008). However, it is also evident that, as complex areas are not fully mapped-out in the germinal zone, environmental influences must also play an important modulatory role during development (Rakic et al. 2009).

Susan Lindsay and colleagues are investigating the origins and location of patterning centres in the human forebrain and have found differences between human and animal models (Kerwin et al. 2010 in this issue). It has been shown in mice that gene expression controlled by morphogenetic gradients includes the expression of transcription factors that in turn control the expression of cell–cell recognition molecules and other markers that determine the phenotype of neural cells (e.g. O’Leary & Borngasser, 2006; O’Leary & Sahara, 2008; Rakic, 2009; Rakic et al. 2009). However, Susan Lindsay has shown how an online atlas of the developing human brain (The HUDSEN Atlas, http://www.ncl.ac.uk/ihg/EADHB/; Wang et al. 2010b) can augment this concept and provide the essential information on gene expression and interactive computer-based 3D models that may be key to understanding the origin of many cognitive disorders that cannot be obtained in any other way (Johnson et al. 2009; Kerwin et al. 2010) (Fig. 2).

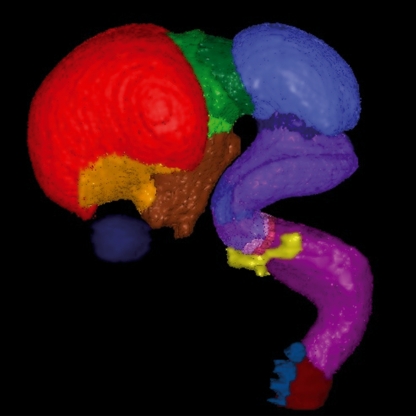

Fig. 2.

Subdivisions of the developing human brain in a 3D virtual model of an embryo at Carnegie Stage 22 (approximately 7–8 gestational weeks). Different regions have been defined and presented in different colours: pallium, red; subpallium, orange; hypothalamus, brown; diencephalon, shades of green; mesencephalon, blue; metencephalon, shades of purple; myelencephalon, magenta; spinal cord, dark red; dorsal root ganglia, blue. For reference the eye has been painted dark blue, and the inner ear yellow. Figure provided by Dr Janet Kerwin, Newcastle University (http://www.HUDSEN.org).

Nadhim Bayatti and colleagues have demonstrated how patterns of gene expression that may represent protomaps in the human neocortex show similarities with animal models but also important differences (Bayatti et al. 2008b; Ip et al. 2010 in this issue), which need to be understood, considering the more complex pattern of arealization observed in humans, and the large plasticity in arealization sometimes observed following a lesion early in human brain development (Basu et al. 2010). Fruitful studies have been made on the development of those regions of the cortex that show the greatest differences with other species in the mature human brain, namely the frontal/prefrontal cortex, perisylvian cortex and in particular Broca's area, the site of speech generation (Abrahams et al. 2007; Judaš & Cepanec, 2007). A recent effort to profile gene expression in the developing human cerebral cortex has revealed a human-specific pattern and modifications, particularly in the areas related to language, such as Broca and Wernicke (Johnson et al. 2009). Pierre Vanderhaeghen and colleagues and other groups have undertaken a transcriptome analysis of these rapidly evolving brain regions (Pollard et al. 2006; see also Konopka et al. 2009). The changes in developmental gene expression patterns and their regulatory networks are of particular importance for understanding the evolutionary processes involved in generating these cortical areas.

It is becoming increasingly clear that many psychiatric illnesses may have developmental origins in the earliest stages of formation of the neocortex. Not only autism, but also schizophrenia and possibly even Alzheimer's disease, could be caused by interactions between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors such as viral infection or toxin exposure during pregnancy (Ben-Ari, 2008). Renzo Guerrini has been involved in work identifying the genes underlying abnormalities of the cortex leading to epilepsy, including genes expressed at different stages of the developmental process, i.e. proliferation, migration and connection formation (Guerrini et al. 2008; Chioza et al. 2009). It is also clear, however, that external events can interfere with the timetable of development leading to brain malformation. Waney Squier and Anne Jansen have investigated how stroke and brain injury in utero, during sensitive periods of development, as well as genetic malformations, lead to epilepsy caused by the erroneous migration of inhibitory interneurons (Hannan et al. 1999; Squier et al. 2003; Squier & Jansen, 2010 in this issue). Alcohol, radiation, diet and infection could all have an impact on cortical development. Some very rare cases of brain injuries are associated with diagnostic procedures (Squier et al. 2000). Pasko Rakic has even suggested that ultrasound examination may impede the migration of developing neurons in embryonic mouse cortex (Ang et al. 2006) and work on this subject in non-human primates is underway. Laurence Garey has presented data suggesting that a specific loss of synaptic connectivity in restricted regions of the cortex in schizophrenics has a neurodevelopmental origin (Lynch et al. 2002; Garey, 2010 in this issue); but is the trigger genetic, or environmental, or both?

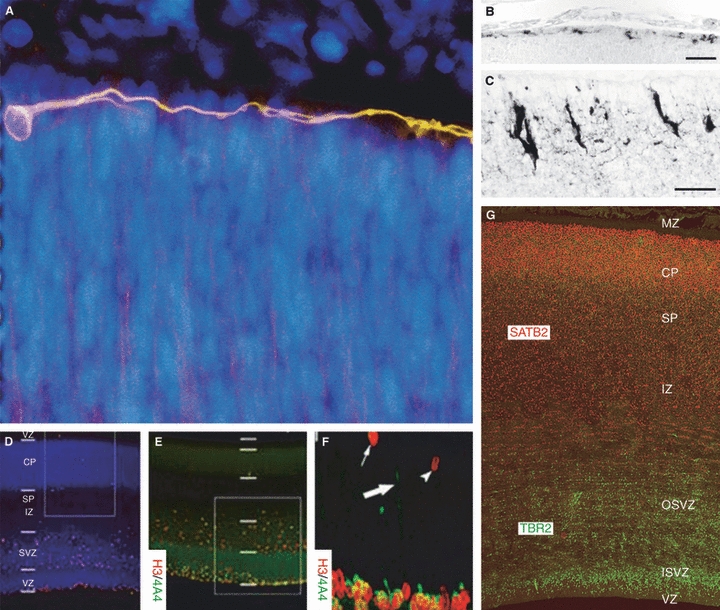

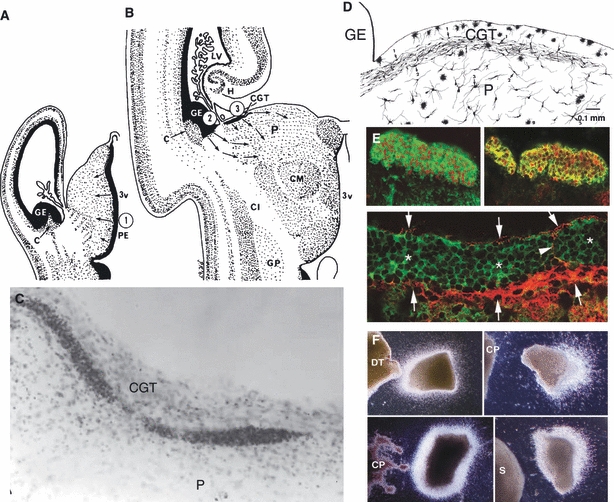

The limitations of studies on non-human cortical development

One of the challenges for the future is to map developmental events precisely in the human in terms of the timing and location of both gene expression and significant events such as neurogenesis, migration and axon pathway formation. Currently, such studies are being performed in animal models, particularly mice, because of the availability of transgenic techniques, and stunning progress is being made [Caviness & Rakic, 1978; Goffinet & Rakic, 2000; Bult et al. 2008; Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) resource at the Jackson Laboratory: http://www.informatics.jax.org]. However, we need to find detailed and precise species-specific differences in the other cortical areas during mouse and human development in order to safely interpret the results of mouse studies with regard to understanding human brain development, and to be aware when mouse–human extrapolations are not appropriate (Manger et al. 2008). Irina Bystron has shown that in human forebrain, unlike rodent, predecessor cells migrate into the cortical primordium from the subpallium even before local neurogenesis has begun (Bystron et al. 2005, 2006; Carney et al. 2007). Predecessor neurons, which migrate tangentially from lower segments of the neuraxis, might initiate the onset of local neurogenesis via pial contacts with stem cells (Fig. 3A). However, there are also other human-specific cell types that migrate tangentially between different brain subdivisions, most of which emerge during later stages of prenatal development (reviewed by Bystron et al., 2008). One of these is tangential migration of GABAergic inerneurons from the ganglionic eminence situated in the ventral telencephalon to the pulvinar and lateral posterior nucleus of the thalamus in the diencephalon (Rakic & Sidman, 1969; Letinic & Rakic, 2001). These neurons stream through an easily detectable transient structure – the corpus gangliothalamicus – that is located beneath the surface of the pulvinar adjacent to the telo-diencephalic sulcus in human fetuses between 18 and 34 weeks of gestational age (GA) (Fig. 4A–C) (Rakic & Sidman, 1969). More recent studies using immunohistochemistry, DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate) labelling and organotypic culture assays indicate that these migrating neurons are glutamate decarboxylase- and distal-less gene-positive and guided by homotypic–neurophilic cues (Fig. 4C–F) (Letinic & Rakic, 2001). The corpus gangliothalamicus and the migrating cells could not be identified in any non-human species so far examined including rodents, carnivores and even non-human primates. Although the human corpus gangliothalamicus contains more cells than the entire mouse ganglionic eminence, and was discovered over 40 years ago (Rakic & Sidman, 1969), only two additional studies (Letinic & Kostović, 1997; Letinic & Rakic, 2001) have so far been devoted to it, in spite of the fact that it is probably functionally and biomedically very important. For example, the human pulvinar is reciprocally connected to the Broca and Wernicke areas and, based on stimulation studies, it has been proposed that it is involved in the processing of language and in specific forms of anomias (Ojemann et al. 1968; Ojeman, 1984). These observations all suggest that cortical evolution must be viewed together with the evolution of the thalamus.

Fig. 3.

Cerebral cortical germinal zone during neurogenesis and the first postmitotic neurons of the human brain. (A) The first postmitotic neurons, the predecessor neurons in the primordial plexiform layer (PPL) of the human cerebral cortex, were revealed with TU-20 immunostaining (orange) in a coronal section of a Carnegie Stage 13 (4–4.5 gestational weeks) dorsal cortex. The predecessor cells and their tangentially oriented processes populate the PPL in the telencephalon, with a clear basal-to-dorsal density gradient prior to local cortical neurogenesis. They are not immunoreactive to reelin. Reelin-expressing Cajal-Retzius cells in mouse embryo cortex at embryonic day 14 (B) and in human fetus cortex at 21 gestational weeks (C). Cajal-Retzius cells increase in numbers and morphological complexity in mammals. Scale bars: 40 μm (B), 20 μm (C). (D–F) At 11 gestational weeks, the human cortical germinal zone consists of the ventricular and subventricular zones (VZ and SVZ, respectively). The intermediate zone (IZ), subplate (SP), cortical plate (CP) and marginal zone (MZ) were also present in the developing cortical wall as revealed by bisbenzimide (blue). H3+ cells were prominent in the VZ and extraventricular compartments. Expression of H3 and 4A4 was studied with double immunohistochemistry (E) and co-expression in these cells was confirmed by confocal microscopy (F), H3 (red) and 4A4 (green). 4A4 immunoreactivity was primarily restricted to the VZ/SVZ although double-positive cells were present in the apical portion of the IZ. The arrowhead indicates a single-labelled pH3-immunorective profile in the SVZ; the small arrow depicts a similar profile in the IZ. A pial-directed process originating from a radial glia in the VZ is indicated by a thick arrow. (G) Further compartmentalization of the germinal zone to internal SVZ (ISVZ) and outer SVZ (OSVZ) is apparent at 12 gestational weeks on a TBR2- and SATB2-immunostained cerebral cortical slice. TBR2, expressed by intermediate neuronal progenitor cells, marks out the proliferative zones, whereas SATB2, expressed by some postmitotic neurons, marks out the IZ, SP, CP and MZ. All parts of this figure are reproduced with permission: A is from Bystron et al. (2006); B,C from Molnár et al. (2006); D–F from Carney et al. (2007); and G was kindly provided by Bui Kar Ip (Newcastle University).

Fig. 4.

A transient, human-specific structure, the corpus gangliothalamicus (CGT), is situated close to the telo-diencephalic junction, between the telecephalic ganglionic eminence (GE) and dorsal thalamus (DT) in human fetal cerebrum. Semi-diagrammatic drawings of the human thalamus at 10 (A) and 24 (B) gestational weeks showing early genesis of thalamic neurons from the local proliferative ependyma, now called ventricular zone and their migration from the GE via the corpus gargliothalamises (CGT) to the pulvinar (P) at early and late fetal stages, respectively. (C) CGT at the surface of the pulvinar (P) in a human 18 gestational week fetus stained with Cresyl violet. (D) Drawing of the Golgi-impregnated images of migrating neurons in the CGT and transitional forms to neurons beneath. (E) Neurons in the CGT double-immunostained with GE-specific marker Dlx 1/2 and Tuj1 and GABA are indicated with arrows and asterisks, respectively. (F) Use of organotypic cultures to assay the attractive effect of the human DT and the repellent effect of the mouse and human choroid plexus (CP) and mouse subthalamic nucleus (S) on neurons migrating from the explants of the human GE. A–D from Rakic & Sidman (1969); E,F from Letinic & Rakic (2001). 3v, third ventricle; C, caudate nucleus; Cl, clausfrum; CM, centrum medianum; GE, ganglionic eminence; GP, globus pallidus; LV, lateral ventricle; H, hippocampus.

The difference in the size and composition of the subventricular zone in human and non-human species may be equally important. Studies of embryonic forebrain at a series of stages reveal that the subventricular zone in human is not only much larger than that of other species (Sidman & Rakic 1973, 1982; Rakic & Sidman, 1968) but that it also appears earlier in development and contains displaced radial glial cells that enhance cortical evolutionary expansion and elaboration (Schmechel & Rakic, 1979; Carney et al., 2007; Molnár et al. 2006; Bayatti et al. 2008a; Bystron et al. 2008; Fish et al. 2008; Hansen et al. 2010; Fietz et al. 2010). Furthermore, it contains a distinct outer and inner sublayer that is also present in non-human primates but not in rodents (Smart et al. 2002; Lukaszewicz et al. 2006; Hansen et al. 2010; Fietz et al. 2010) (Fig. 3D–G).

Human-specific aspects of the earliest stages of cortical development

Gundela Meyer has shown that the earliest cortical structure, the preplate, has a more complex structure in humans than in rodents (Meyer, 2007, 2010 in this issue) (Fig. 3B,C). It includes the Cajal-Retzius cells, important in guiding cell migration, and pioneer neurons that form the first axons to leave the cortex (Suárez-Solá et al. 2009). The role of both of these early-generated cell populations may be a good deal more complicated in human than in rodent. In addition, layer I in the fetal cerebral cortex of human and non-human primates contains a large subpial granular layer that does not exist in rodents and other animals (Brun, 1965; Gadisseux et al. 1992; Zecevic and Rakic, 2001). This transient proliferative layer may produce interneurons that are involved in human-specific psychiatric disorders. Pierre Vanderhaeghen and colleagues have identified an RNA gene that is rapidly evolving in humans and is expressed by Cajal-Retzius cells (Pollard et al. 2006). Milos Judaš has described a population of nitrinergic interstitial neurons that transiently populate the fetal white matter and are distinct from subplate neurons. Re-examination of the original publications and material has revealed that interstitial neurons, subplate neurons and the subplate zone were first observed and variously described in large brains of gyrencephalic mammals (including human), characterized by an abundant white matter and slow and protracted prenatal and postnatal development (Judaš et al. 2010a,b;, both in this issue). These fetal interstitial neurons are poorly developed or absent in the brains of rodents but they represent a prominent feature of the significantly enlarged white matter of human and non-human primate brains (Kostović & Rakic, 1980; Suárez-Solá et al. 2009). The number of interstitial neurons subjacent to some cortical areas is larger than the number of the thalamic neurons that project into these areas, yet their function and possible role in human mental disorder is completely unknown.

The cortical subplate shows important differences between human and rodents (reviewed by Ayoub & Kostovic, 2009; Kanold & Luhmann, 2010; Wang et al. 2010b in this issue). This transient, developmental structure is the first site of synapse formation in the cortex and the first region to receive inputs from the thalamus and other regions; its functioning is crucial to establishing the correct wiring and functional maturation of the cerebral cortex. For example, the subplate zone reaches its largest size and survives longest in the regions subjacent to the association cortices that contain transient cortico-cortical and callosal connections before they enter the cortical plate (Kostović & Rakic, 1990). More recently, Ivica Kostović and Mary Rutherford have carried out extensive research comparing MRI data with histological sections to demonstrate how vastly larger and more elaborate the human subplate is compared with that of other species (Kostović et al. 2002; Kostović & Vasung, 2009; Perkins et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2010b in this issue). Donna Ferriero has demonstrated the vulnerability of the subplate in premature babies with in-vivo imaging (McQuillen & Ferriero, 2005; Ferriero & Miller, 2010 in this issue). We have presented data showing the evolution and changes in gene expression and complexity of the subplate between species (Hoerder-Suabedissen et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009; Bayatti et al. 2008a; Wang et al. 2010b in this issue). Recently it has been shown that during human fetal brain development in some of the prospective association areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, sets of genes are expressed that are not expressed in rodents (Johnson et al. 2009).

Another significant rodent/primate species difference is in the manner of origin of inhibitory interneurons in the neocortex. A remarkable discovery made in rodents was that these interneurons are born almost entirely outside the dorsal telencephalon, in the subpallium, from which they migrate tangentially into the cortex (reviewed in Marin & Rubenstein, 2001). However, it has also been shown by Rakic and colleagues, using immunohistochemistry and retroviral labelling of slice preparations, that at later stages of human fetal development in some areas, e.g. prospective visual cortex, the majority of interneurons are actually generated within the cortical progenitor zones (Letinic et al. 2002). This interpretation was supported by the use of double-label immunohistochemistry (Zecevic et al. 2005; Mo & Zecevic, 2008) and in the analysis of malformations that involve deletion of the ganglionic eminence (Fertuzinhos et al. 2009). Studies carried out in non-human primates have confirmed this to be the case at least in the macaque monkey (Petanjek et al. 2009). However, the most recent immunohistochemical study of the 15 GA human did not reveal double GABA-labelled postmitotic cells in the subventricular zone (Hansen et al. 2010), whereas they were detected in 20 GA fetus (Zecevic et al. 2010). Clearly, this field needs more work to delineate the specific areas and stages of prolonged human development at which the appropriate complement of distinct inerneuronal subtypes is received. This is an important issue as failures in proliferation and migration of the specific classes of inhibitory interneurons have been implicated in diverse conditions including autism, epilepsy and schizophrenia, and we must question whether our mouse models are appropriate for the study of these diseases (Levitt, 2005; Lewis & Hashimoto, 2007; Jones, 2009; Hannan et al. 1999) (Fig. 5E).

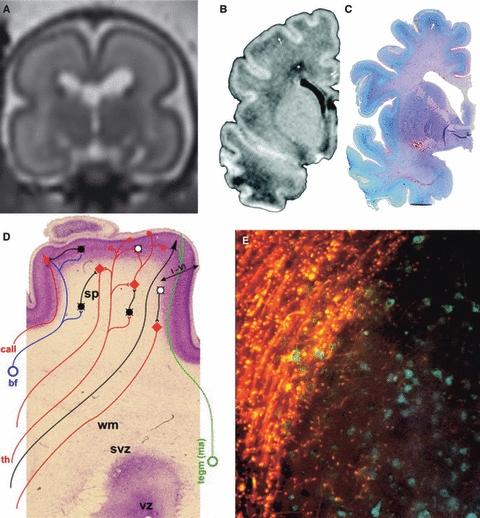

Fig. 5.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and histological investigations on subplate neurons in human and development of early human cortical circuits. (A) In-utero MRI of the fetal subplate. The layers of the hemisphere are clearly seen on the T2-weighted single-shot images in the coronal plane acquired in a fetus at 23 gestational weeks using a 1.5 T scanner. The subplate is seen as high signal intensity, reflecting its hydrophilic extracellular matrix. At this stage of development the subplate is thicker than the cortex. The developing white matter has a low signal intensity band reflecting increased cellular content (reproduced with permission from Wang et al. 2010b this issue). Low-power view of T1-weighted MRI (B) and Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained coronal sections (C) through the brains of premature newborns at 36 gestational weeks demonstrating the gradual dissolution of the subplate zone. Reproduced with permission from Kostović et al. (2002). (D) Schematic summary of the neuronal elements involved in early human cortical circuits superimposed on a Nissl-stained section of a 34 gestational week preterm human infant. This period is characterized by the co-existence of transient circuitry in the subplate zone and elaboration of permanent (sensory-driven) circuitry in the cortical plate. Note the initial six layers (I–VI) and the increase in GABAergic neurons (white circles) in the cortical plate. GABAergic neurons, black circles; glutamatergic neurons, red diamond; cortical plate neurons, violet. Afferents from the basal forebrain (bf, blue), monoaminergic brain stem nuclei (tegm, green) and thalamus (th, red). call, callosal fibers; wm, white matter; svz, subventricular zone; vz, ventricular zone. Reproduced with permission from Kostović & Judaš (2007). (E) Neuronal heterotopias are seen in various pathologies and are associated with intractable epilepsy. Studies using histological and carbocyanine dye (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate) tracing techniques in selected cases of subcortical or periventricular nodular heterotopia revealed abnormally differentiated neurons with altered connectivity. Bisbenzimide labelling (blue) reveals the cells and boundaries of the nodules and DiI labelling (orange) demonstrates the vast majority of labelled fibres coursing around but not within the nodules. Some fibres are extending across the margin of the nodule and have punctate termini close to cell bodies within the nodules. Reproduced with permission from Hannan et al. (1999).

Brain development cannot be understood without contemplating the associated vascular development. Several interactions have been described recently between the developing nervous system and its vasculature (Javaherian & Kriegstein, 2009; Stubbs et al. 2009; Nie et al. 2010). Some of the signalling molecules involved in vascular development are also involved in the formation of the blood–brain barrier (Daneman et al. 2009). Kjeld Møllgård and colleagues have highlighted the differences between the development of the blood–brain barrier and other interfaces between blood, cerebrospinal fluid and extracellular fluid in the brain in humans and other species, and the importance of these barriers in controlling the access of morphogenetic molecules to receptors on brain cells (Saunders et al. 1991, 2008).

The impact of imaging techniques in mapping human brain development

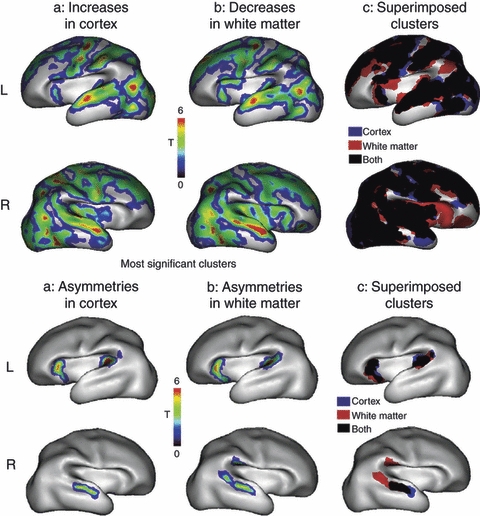

The rapid advancement of MRI is allowing important progress in the understanding of normal and pathological human brain development. Structural MRI data from scanning in vivo, in utero and postmortem, combined with diffusion tensor imaging, are allowing us to map development of the human brain. The growth of axon pathways and the relative rates of growth of different regions of the cortex in terms of relative grey and white matter volumes, and the duration of transient structures such as the subventricular zone and subplate, may now all be examined in this way. Ivica Kostović, who made the original discovery of the subplate zone (see Kostović & Rakic, 1990), has more recently compared diffusion tensor imaging studies with histological sections to illustrate axon pathway formation in the forebrain (Kostović & Vasung, 2009; Vasung et al. 2010) (Fig. 5). Petra Hüppi and Mary Rutherford have compared data obtained from the perinatal imaging of both healthy babies and babies with potential neonatal brain injury in the hope that scanning can be used confidently to predict the outcome of perinatal strokes or hypoxic episodes in premature babies (Ment et al. 2009; Rutherford et al. 2010). 3D MRI has been employed to measure brain tissue volumes (cerebral cortical grey matter, white matter), surface area and the sulcation index and has shown cortical phenotypes associated with early behavioural development measured with neurobehavioral assessment at term and later in development. There is a close relationship between the cortical surface at birth and neurobehavioral scores (Dubois et al. 2008). Hüppi and colleagues have mapped the development of early asymmetries over the immature cortex, and voxel-based analyses of cortical and white matter masks were performed over a group of newborns from 26 to 36 gestational weeks (Dubois et al. 2010). Interindividual variations were first detected in large cerebral regions and the right and left hemispheres were compared (Fig. 6). The first asymmetric cortical areas were in the left perisylvian regions. This suggests the emergence of anatomical lateralization in language processing prior to language exposure (Dubois et al. 2010).

Fig. 6.

Age-associated interindividual variations in cortical development have been studied with non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging. Postprocessing of high-quality T1- and T2-weighted images enabled the segmentation of the cortex in large regions across both hemispheres of the brain. Dedicated postprocessing tools enabled the quantitative study of the variations with increases in the cortex (a) and decreases in white matter (b) for the left (L, up) and right (R, down) hemispheres in the preterm newborn. The first two rows show statistical T-maps (colour coded blue to red) that are superposed to the 3D averaged cortical surface. Significant clusters showing ‘apparent increases’ in cortex (a) and ‘apparent decreases’ in white matter (b). (c) The clusters for the cortex (blue) and white matter (red) had considerable overlay (black). Note that the right hemisphere shows larger regions of age-associated variations in comparison with the left. In the third row, statistical T-maps are presented with the most significant clusters along the horizontal, coronal and parasagittal planes. In the lower two rows interhemispherical asymmetries are shown in the preterm group; statistical T-maps are superposed to the 3D averaged cortical surface in the significant clusters showing asymmetries in cortex (a) and white matter (b), for the left (L, up) and right (R, down) hemispheres. The clusters (c) for cortex (blue) and white matter (red) are mainly overlying (black). Reproduced with permission from Dubois et al. (2010).

The outcome of injury in the developing brain differs from effects in the adult

Donna Ferreiro and colleagues have imaged the biochemistry of hypoxia in the developing human brain (Vigneron, 2006) and shown the delayed development of myelination of the affected axon tracts (McQuillen & Ferriero, 2005; Miller & Ferriero, 2009; Ferriero & Miller, 2010 in this issue). Catherine Verney and Mary Rutherford have described how microglia colonize the developing human telencephalon and the role that they play in white matter injury (Monier et al. 2007; Verney et al. 2010 in this issue).

Injury to the cortex and to subcortical white matter tracts leads to conditions such as cerebral palsy that can involve functional reorganization of cortical areas and projections. James Bourne has described how multiple cortical visual areas develop in the primate brain (Bourne & Rosa, 2006; Burman et al. 2007; Bourne, 2010 in this issue) and has shown that focal lesions in the immature brain lead to reorganization of the cortex in different ways to lesions in the adult brain, an issue that has been addressed in various model systems (Huffman et al. 1999). Similarly, Janet Eyre and colleagues and Martin Staudt and colleagues have used a battery of techniques, including MRI and neurophysiological recordings in human subjects, to investigate different types of reorganization of the sensorimotor cortex and corticospinal tract in response to developmental lesions as compared with the effects of lesions in the adult (Basu et al. 2010; Eyre et al. 2007; Walther et al. 2009; Staudt, 2010 in this issue). Martin Staudt and colleagues showed that when a lesion prevents formation of a direct pathway from the origin to the appropriate target the axonal tracts extend around the lesion and nevertheless reach appropriate targets, directly supporting the principle of the protomap hypothesis (Rakic, 1988) in the human brain. Older concepts of plasticity regarded the immature brain as inherently more plastic and able to overcome lesions; however, we now understand that aberrant plasticity in response to lesions can lead to the symptoms of cerebral palsy and related conditions (Clowry, 2007; Eyre, 2007). With improvements in imaging now allowing us to predict more accurately the outcome of neurodevelopmental lesions, could we, in the future, intervene to guide plasticity along a reparative course?

It is inevitable that further developments in this field will require national and international coordination of research. Recent developments in human embryonic brain banking in the UK (Lindsay & Copp, 2005), the on-line encyclopedia-type project MOCA (Museum of Comparative Anthropogeny), the emerging mouse and human gene expression databases [Allen Brain Institute; Jones et al. 2009; Gensat, International Coordinating Facility (INCF) for Informatics] and clinical image libraries now provide excellent opportunities for accelerated progress in understanding development of the human neocortex. The next generation of sequencing methods and developments in bioinformatics will enable us to lift the platform of our analysis to a much higher level, with global transcriptome analysis during development and in disease (Johnson et al. 2009). It is imperative that the knowledge and the implications of the fundamental observations are transferred to the clinic in a timely fashion. We hope that the reviews presented in this issue will facilitate and enhance the dialogue between basic researchers and clinicians.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of our laboratories and to Gillian Morriss-Kay for critically reading various versions of this manuscript.

References

- Abrahams BS, Tentler D, Perederiy JV, et al. Genome wide analyses of human perisylvian cerebral cortical patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17849–17854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706128104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang ES, Jr, Gluncic V, Duque A, et al. Prenatal exposure to ultrasound waves impacts neuronal migration in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12903–12910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605294103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub AE, Kostovic I. New horizons for the subplate zone and its pioneering neurons. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1705–1707. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Graziadio S, Smith M, et al. Developmental plasticity connects visual cortex to motoneurons after stroke. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:132–136. doi: 10.1002/ana.21827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Brito R, Machold R, Klein C, et al. Gene expression in cortical interneuron precursors is prescient of their mature function. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2306–2317. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayatti N, Moss JA, Sun L, et al. A molecular neuroanatomical study of the developing human neocortex from 8 to 17 postconceptional weeks revealing the early differentiation of the subplate and subventricular zone. Cereb Cortex. 2008a;18:1536–1548. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayatti N, Sarma S, Shaw C, et al. Progressive loss of PAX6, TBR2, NEUROD and TBR1 mRNA gradients correlates with translocation of EMX2 to the cortical plate during human cortical development. Eur J Neurosci. 2008b;28:1449–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. Neuro-archaeology: pre-symptomatic archi-tecture and signature of neurological disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:626–636. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulder Committee. Embryonic vertebrate central nervous system: revised terminology. Anat Rec. 1970;166:257–261. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091660214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne JA. Unravelling the development of the visual cor-tex: implications for plasticity and repair. J Anat. 2010;217:449–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne JA, Rosa MG. Hierarchical development of the primate visual cortex, as revealed by neurofilament immunoreactivity: early maturation of the middle temporal area (MT) Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:405–414. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. Beitraege zur histologischen Lokalisation der Grosshirnrinde. VI. Mitteilung: Die Cortexgliederung des Menschen. J Psychol Neurol. 1908;10:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Brun A. The subpial granular layer of the foetal cerebral cortex in man. Its ontogeny and significance in congenital cortical malformations. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;179(Suppl):3–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, et al. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): mouse biology and model systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D724–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm961. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman KJ, Lui LL, Rosa MG, et al. Development of non-phosphorylated neurofilament protein expression in neurones of the New World monkey dorsolateral frontal cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:1767–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystron I, Molnár Z, Otellin V, et al. Tangential networks of precocious neurons and early axonal outgrowth in the embryonic human forebrain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2781–2792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4770-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystron I, Rakic P, Molnár Z, et al. The first neurons of the human cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:880–886. doi: 10.1038/nn1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystron I, Blakemore C, Rakic P. Development of the human cerebral cortex: Boulder Committee revisited. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:110–122. doi: 10.1038/nrn2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RSE, Bystron I, López-Bendito G, et al. Developmental changes in pre- and post-cortical plate formation patterns of abventricular mitoses in rodent and human cortex. Brain Struct Funct. 2007;212:37–54. doi: 10.1007/s00429-007-0142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness VS, Jr, Rakic P. Mechanisms of cortical development: a view from mutations in mice. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1978;1:297–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.01.030178.001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chioza BA, Aicardi J, Aschauer H, et al. Genome wide high density SNP-based linkage analysis of childhood absence epilepsy identifies a susceptibility locus on chromosome 3p23-p14. Epilepsy Res. 2009;87:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholfin JA, Rubenstein JL. Patterning of frontal cortex subdivisions by Fgf17. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7652–7657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702225104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowry GJ. The dependence of spinal cord development on corticospinal input and its significance in understanding and treating spastic cerebral palsy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:1114–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R, Agalliu D, Zhou L, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for CNS, but not non-CNS, angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:641–646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805165106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J, Benders M, Borradori-Tolsa C, et al. Primary cortical folding in the human newborn: an early marker of later functional development. Brain. 2008;131:2028–2041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J, Benders M, Lazeyras F, et al. Structural asymmetries of perisylvian regions in the preterm newborn. Neuroimage. 2010;52:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre JA. Corticospinal tract development and its plasticity after perinatal injury. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:1136–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre JA, Smith M, Dabydeen L, et al. Is hemiplegic cerebral palsy equivalent to amblyopia of the corticospinal system? Ann Neurol. 2007;62:493–503. doi: 10.1002/ana.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero DM, Miller SP. Imaging selective vulnerability in the developing nervous system. J Anat. 2010;217:429–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertuzinhos S, Krsnik Z, Kawasawa YI, et al. Selective depletion of molecularly defined cortical interneurons in human holoprosencephaly with severe striatal hypoplasia. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietz SA, Kelava I, Vogt J, et al. OSVZ progenitors of human and ferret neocortex are epithelial-like and expand by integrin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:690–699. doi: 10.1038/nn.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JL, Dehay C, Kennedy H, et al. Making bigger brains – the evolution of neural-progenitor-cell division. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 17):2783–2793. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi-Shimogori T, Grove EA. Emx2 patterns the neocortex by regulating FGF positional signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:825–831. doi: 10.1038/nn1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadisseux JF, Goffinet AM, Lyon G, et al. The human transient subpial granular layer: an optical, immunohisto-chemical, and ultrastructural analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:94–114. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L. When cortical development goes wrong: schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disease of micro-circuits. J Anat. 2010;217:324–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet AM, Rakic P, editors. Mouse Brain Development Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation. Bernon, NewYork: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Dobyns WB, Barkovich JA. Abnormal development of the human cerebral cortex: genetics, functional consequences and treatment options. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan AJ, Servotte S, Katsnelson A, et al. Character-ization of nodular neuronal heterotopia in children. Brain. 1999;122:219–238. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Lui HJ, Parker PRL, et al. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature08845. (14 February 2010) doi: 10.1038/Nature08845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- His W. Die entwicklung des menschlichen Gehirns während der ersten Monate. Leipzig: Hirzel; 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstetter F. Beiträge zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des menschlichen Gehirns I. Vienna: Dueticke; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Wang WZ, Lee S, et al. Novel markers reveal subpopulations of subplate neurons in the murine cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;9:1738–1750. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman K, Molnár Z, van Dellen A, et al. Compression of sensory fields on a reduced cortical sheet. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9939–9952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-09939.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip BK, Wappler I, Peters H, et al. Investigating gradients of gene expression involved in early human cortical development. J Anat. 2010;217:300–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaherian A, Kriegstein A. A stem cell niche for intermediate progenitor cells of the embryonic cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(Suppl 1):i70–i77. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Imamura Kawasawa Y, Mason CE, et al. Functional and evolutionary insights into human brain development through global transcriptome analysis. Neuron. 2009;62:494–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. The origins of cortical interneurons: mouse versus monkey and human. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1953–1956. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AR, Overly CC, Sunkin SM. The Allen Brain Atlas: 5 years and beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:821–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judaš M, Cepanec M. Adult structure and developments of the human fronto-opercular cerebral cortex (Broca's region) Clin Linguist Phon. 2007;21:975–989. doi: 10.1080/02699200701617175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judaš M, Sedmak G, Pletikos M. Early history of subplate and interstitial neurons: from Theodor Meynert (1867) to the discovery of the subplate zone (1974) J Anat. 2010a;217:344–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judaš M, Sedmak G, Pletikos M, et al. Populations of subplate and interstitial neurons in fetal and adult human telencephalon. J Anat. 2010b;217:381–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanold PO, Luhmann HJ. The subplate and early cortical circuits. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:23–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwin J, Yang Y, Merchan P, et al. The HUDSEN Atlas: a three-dimensional (3D) spatial framework for studying gene expression in the developing human brain. J Anat. 2010;217:289–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka G, Bomar JM, Winden K, et al. Human-specific transcriptional regulation of CNS development genes by FOXP2. Nature. 2009;462:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature08549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostović I, Judaš M. Transient patterns of cortical lamination during prenatal life: do they have implications for treatment? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:1157–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostović I, Rakic P. Cytology and time of origin of interstitial neurons in the white matter in infant and adult human and monkey telencephalon. J Neurocytol. 1980;9:219–242. doi: 10.1007/BF01205159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostović I, Rakic P. Developmental history of the transient subplate zone in the visual and somatosensory cortex of the macaque monkey and human brain. J Comp Neurol. 1990;297:441–470. doi: 10.1002/cne.902970309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostović I, Vasung L. Insights from in vitro fetal magnetic resonance imaging of cerebral development. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:220–233. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostović I, Judaš M, Rados M, et al. Laminar organization of the human fetal cerebrum revealed by histochemical markers and magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:536–544. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K, Kostović I. Transient fetal structure, the gangliothalamic body, connects telencephalic germinal zone with all thalamic regions in the developing human brain. J Comp Neurol. 1997;384:373–395. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970804)384:3<373::aid-cne5>3.3.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K, Rakic P. Telencephalic origin of human thalamic GABAergic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:931–936. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K, Zoncu R, Rakic P. Origin of GABAergic neurons in the human neocortex. Nature. 2002;417:645–649. doi: 10.1038/nature00779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P. Disruption of interneuron development. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 7):22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T. Deciphering the disease process of schizophrenia: the contribution of cortical GABAergic neurons. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:109–131. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Copp AJ. MRC-Wellcome Trust Human Develop-mental Biology Resource: enabling studies of human developmental gene expression. Trends Genet. 2005;21:586–590. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodygensky GA, Vasung L, Sizonenko SV, et al. Neuroimaging of cortical development and brain connectivity in human newborns and animal models. J Anat. 2010;217:418–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewicz A, Cortay V, Giroud P, et al. The concerted modulation of proliferation and migration contributes to the specification of the cytoarchitecture and dimensions of cortical areas. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(Suppl 1):i26–i34. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch A, Gentleman S, Garey L. Further observations on neuronal somata and dendrites in chronic schizophrenia. J Anat. 2002;200:213. [Google Scholar]

- Manger PR, Cort J, Ebrahim N, et al. Is 21st century neuroscience too focussed on the rat/mouse model of brain function and dysfunction? Front Neuroanat. 2008;2:5. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.005.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Rubenstein JL. A long, remarkable journey: tangential migration in the telencephalon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:780–790. doi: 10.1038/35097509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillen PS, Ferriero DM. Perinatal subplate neuron injury: implications for cortical development and plasticity. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:250–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ment LR, Hirtz D, Hüppi PS. Imaging biomarkers of outcome in the developing preterm brain. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1042–1055. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G. Genetic control of neuronal migrations in human cortical development. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2007;189:1–11. 1 p preceding 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G. Building a human cortex: the evolutionary differentiation of Cajal-Retzius cells and the cortical hem. J Anat. 2010;217:334–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SP, Ferriero DM. From selective vulnerability to connectivity: insights from newborn brain imaging. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z, Zecevic N. Is Pax6 critical for neurogenesis in the human fetal brain? Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1455–1465. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Métin C, Stoykova A, et al. Comparative aspects of cerebral cortical development. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:921–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier A, Adle-Biassette H, Delezoide AL, et al. Entry and distribution of microglial cells in human embryonic and fetal cerebral cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:372–382. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180517b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie K, Molnár Z, Szele F. Neuroblast proliferation but not migration is associated with a vascular niche during development of the rostral migratory stream. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:163–172. doi: 10.1159/000301135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeman GA. Common cortical and thalamic mechanisms for language and motor functions. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:R901–R903. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.6.R901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojemann GA, Fedio P, Van Buren JM. Anomia from pulvinar and subcortical parietal stimulation. Brain. 1968;91:99–116. doi: 10.1093/brain/91.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DDM. Do cortical areas emerge from a protocortex? Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:400–406. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DDM, Borngasser D. Cortical ventricular zone progenitors and their progeny maintain spatial relationships and radial patterning during preplate development indicating an early protomap. Cereb Cortex. 2006;1(Suppl):i46–i56. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DDM, Sahara S. Genetic regulation of arealization of the cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins L, Hughes E, Srinivasan L, et al. Exploring cortical subplate evolution using magnetic resonance imaging of the fetal brain. Dev Neurosci. 2008;3:211–220. doi: 10.1159/000109864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanjek Z, Berger B, Esclapez M. Origins of cortical GABAergic neurons in the cynomolgus monkey. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:249–262. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, et al. An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature. 2006;443:167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature05113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science. 1988;241:170–176. doi: 10.1126/science.3291116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Sidman RL. Supravital DNA synthesis in the developing human and mouse brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1968;27:246–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Sidman RL. Telencephalic origin of pulvinar neurons in the fetal human brain. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1969;29:53–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00521955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Suner I, Williams RW. A novel cytoarchitectonic area induced experimentally within the primate visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2083–2087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Ayoub AE, Breunig JJ, et al. Decision by division: making cortical maps. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford M, Ramenghi LA, Edwards AD, et al. Assessment of brain tissue injury after moderate hypothermia in neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: a nested substudy of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:39–45. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70295-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders NR, Dziegielewska KM, Møllgård K. The importance of the blood-brain barrier in fetuses and embryos. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:14–15. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90176-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders NR, Ek CJ, Habgood MD, et al. Barriers in the brain: a renaissance? Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmechel DE, Rakic P. Golgi study of radial glial cells in developing monkey telencephalon: Morphogenesis and transformation into astrocytes. Anat Embryol. 1979;156:115–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL, Rakic P. Neuronal migration with special reference to developing human brain: a review. Brain Res. 1973;62:1–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL, Rakic P. Development of the human central nervous system. In: Haymaker W, Adams RD, editors. Histology and Histopathology of the Nervous System. Springfield: C.C. Thomas; 1982. pp. 3–145. [Google Scholar]

- Smart IH, Dehay C, Giroud P, et al. Unique morphological features of the proliferative zones and postmitotic compartments of the neural epithelium giving rise to striate and extrastriate cortex in the monkey. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:37–53. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squier W, Jansen A. Abnormal development of the human cerebral cortex. J Anat. 2010;217:312–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squier M, Chamberlain P, Zaiwalla Z, et al. Five cases of brain injury following amniocentesis in mid-term pregnancy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:554–560. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squier W, Salisbury H, Sisodiya S. Stroke in the developing brain and intractable epilepsy: effect of timing on hippocampal sclerosis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:580–585. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203001075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt M. Reorganization after pre- and perinatal brain lesions. J Anat. 2010;217:469–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs D, DeProto J, Nie K, et al. Neurovascular congruence during cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2009;1(Suppl):i32–i41. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Solá ML, González-Delgado FJ, Pueyo-Morlans M, et al. Neurons in the white matter of the adult human neocortex. Front Neuroanat. 2009;3:7. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.007.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasung L, Huang H, Jovanov-Milošević N, et al. Development of axonal pathways in the human fetal fronto-limbic brain: histochemical characterization and diffusion tensor imaging. J Anat. 2010;217:400–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verney C, Monier A, Fallet-Bianco C, et al. Early microglial colonization of the human forebrain and possible involvement in periventricular white-matter injury of preterm infants. J Anat. 2010;217:436–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron DB. Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of human brain development. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2006;16:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther M, Juenger H, Kuhnke N, et al. Motor cortex plasticity in ischemic perinatal stroke: a transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional MRI study. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WZ, Oeschger F, Lee S, et al. High quality RNA from multiple brain regions simultaneously acquired by laser capture microdissection. BMC Molecular Biology. 2009;10:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lindsay S, Baldock R. From spatial-data to 3D models of the developing human brain. Methods. 2010a;50:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WZ, Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Oeschger FM, et al. Subplate in the developing cortex of mouse and human. J Anat. 2010b;217:368–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic N, Chen Y, Filipovic R. Contributions of cortical subventricular zone to the development of the human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:109–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.20714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic N, Hu F, Jakovcevski I. Cortical interneurons in the developing human neocortex. J Neurobiol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/dneu.20812. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic N, Rakic P. Development of layer I neurons in the primate cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5607–5619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05607.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]