Abstract

Background/Objective

Early pubertal timing in females is associated with psychosocial problems throughout adolescence, but it is unclear whether these problems persist into young adulthood.

Methods

Data are from the prospective, population-based Great Smoky Mountains Study (N = 1,420) which initially recruited children at ages 9, 11, and 13 and followed them into young adulthood. Pubertal timing was defined based upon self-reported Tanner stage and age of menarche. Outcomes included functioning related to crime, substance use, school/peer problems, family relationships, sexual behavior and mental health in adolescence (ages 13 to 16) and crime, substance use, education/SES, sexual behavior and mental health in young adulthood (ages 19 and 21).

Results

In adolescence, early maturing females displayed higher levels of self-reported criminality, substance use problems, social isolation, early sexual behavior, and psychiatric problems. By young adulthood, most of these differences had attenuated: Functioning for early maturers improved in some areas (recovery); in others, on-time/late maturers had caught up with their early maturing peers. Nevertheless, early maturing females, particularly those with a history of adolescent conduct disorder, were more likely to be depressed in young adulthood compared to their counterparts. Early maturers were also more likely to have had many sexual partners.

Conclusion

The effects of early pubertal timing on adolescent psychosocial problems were wide-ranging, but diminished by young adulthood for all but a small group.

Introduction

Puberty is a biologically-driven developmental transition with complex secondary effects on social, emotional, and sexual development[1]. Interindividual variation in the timing of pubertal processes creates a period of contrast in which same-aged females differ significantly with respect to highly-salient physical attributes such as breast size, distribution of subcutaneous fat, hip-to-waist ratio, and body hair. Girls who mature earliest are at greater risk for a range of psychological, behavioral and social problems in adolescence, including higher rates of conduct problems (e.g., [2–6]), substance-related problems (e.g., [3, 4, 7, 8]), and precocious sexuality (e.g., [5, 9, 10]). Most of the evidence also suggests increased risk for adolescent depression, anxiety and general emotional distress (e.g., [4, 11–14]), and the evidence is mixed in relation to educational outcomes (e.g., [15–18]). This period of increased risk persists across adolescence even after later-developing peers have physically matured [4, 10, 11]. It is uncertain, however, whether this period of risk extends persists into young adulthood when almost all young women have been physically and sexually mature for some years.

Various hypotheses exist concerning the longer-term outcomes of early puberty, but few studies have the necessary longitudinal data to test them. The persistence hypothesis postulates that negative outcomes of early puberty in adolescence (early sexual initiation, substance use, and delinquent behavior) are self-propagating and continue unabated into young adulthood. The evidence, however, better supports what we call the selective persistence hypothesis.

According to the selective persistence hypothesis, extricating oneself from a pattern of adolescent behavioral problems is a protracted process for early maturers. Failures in limited areas (social, educational) may persist even after recovery from behavior problems (early delinquency, precocious/risky sexuality)[19–21]. Early maturation may orient girls toward early motherhood with limited educational and occupational prospects, increasing their risk for select psychiatric outcomes (emotional and substance-related). The most extensive analysis of the long-term impact of early maturation supported the selective persistence hypothesis: Early maturing females ceased to have behavior problems in adulthood, including criminal offenses and substance use, but they nevertheless had more children than their same-sex peers by age 25, and there was some evidence of lower educational and occupational attainment[5]. An earlier cohort study had shown similar effects on age of marriage and first conception[22]. These studies did not formally assess psychiatric status, however. This hypothesis also raises the possibility that long-term effects may only be apparent for early maturers with the most serious problems or those with long-lasting negative consequences (e.g., teen parenthood).

The attenuation hypothesis posits that the effects of early maturation will be most pronounced immediately following the period of off-time development, but that these effects will attenuate by young adulthood, because (a) early maturers recover from the adverse effects of early pubertal timing, and/or (b) on-time/late maturers catch up in their physical development and now display similar adult-typical behaviors, particularly status-related behaviors such as alcohol use or involvement in sexual activities. This hypothesis was supported by the young adult follow-up of the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project [23], which revealed no effect of early maturation on current young adult psychopathology or role attainment and only modest effects on the quality of social networks. Their finding that lifetime rates of depression, anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders were still elevated was consistent with attenuation, suggesting that early maturers had recovered. Similar attenuated effects in young adulthood were observed in a study using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health which looked at levels of depressed mood over time[12]. Both studies, however, employed pubertal timing measures that were largely retrospective – assessed after most girls had already reached maturity – rather than direct measurement of pubertal milestones throughout the pubertal transition.

Reviewing the literature on early maturing females in 1990, Stattin and Magnusson noted a “scarcity of systematic studies addressing the issue of long-range impact” p. 301[5]. Almost twenty years later, only one additional study (the Oregon study discussed above) has examined a range of outcomes in early-maturing girls in adulthood. Thus, conclusions about the long-term effects of pubertal timing are largely based upon studies of subjects born over 50 years ago[15, 24]. Our aim, therefore, is to test the long-term effects of pubertal timing on crime, substance, educational/SES, sexual, and psychiatric outcomes in cohorts born after 1980.

Methods

Participants

The Great Smoky Mountains Study is a longitudinal study of the development of psychiatric disorder in rural and urban youth14–19. A representative sample of three cohorts of children, age 9, 11, and 13 at intake, was recruited from 11 counties in western North Carolina using a household equal probability, accelerated cohort design20. The externalizing problems scale of the Child Behavior Checklist was administered to a parent of the first stage sample (N=3,896). All children scoring in the top 25%, plus a 1-in-10 random sample of the rest were recruited for detailed interviews. Ninety-five percent of families contacted completed the telephone screen. About 8% of the area residents and the sample are African American, and fewer than 1% are Hispanic. American Indians make up only about 3% of the study area but were oversampled to constitute 25% of the sample. All subjects were given a weight inversely proportional to their probability of selection, so that the results are representative of the population from which the sample was drawn. Of all subjects recruited, 80% (N=1420) agreed to participate. The sample was 49.0% female (N=630). Table 1 presents the study design and participation rates at each wave. This paper presents data on 4021 parent-child pairs of interviews carried out across the age range 9 through 21.

Table 1.

Great Smoky Mountains Study: Data collection by cohort

| Cohort | Age | 1993 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A N=508 | 9 | A1 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | A2 | |||||||||||||

| B N=497 | 11 | B1 | A3 | |||||||||||

| 12 | B2 | A4 | ||||||||||||

| C N=415 | 13 | C1 | B3 | |||||||||||

| 14 | C1 | B4 | A5 | |||||||||||

| 15 | C3 | B5 | A6 | |||||||||||

| 16 | C4 | B6 | A7 | |||||||||||

| 19 | C5 | B7 | A8 | |||||||||||

| 21 | C6 | B8 | A9 | |||||||||||

| Participation% | 94* | 91 | 87 | 78 | 80 | 81 | 74 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 76 |

Light shading indicates the adolescent observations, and dark shading indicates young adulthood observations.

Attrition rates are based upon any individual who participated in at least one assessment. A few children missed or refused to participate in the first assessment, but participated in subsequent assessments.

Procedures

The parent and subject were interviewed by trained interviews separately (as close as possible to the subject’s birthday) until the subject was 16, and subjects only at ages 19 and 21. Before the interviews began, the parent and child signed informed consent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Each parent and child was paid for their participation.

Pubertal Timing

At each assessment up to age 16, self-ratings of current pubertal morphologic status based on the standard Tanner staging system[25] (i.e., five-point scale from I (prepubertal) to V (adult)) and age of menarche were assessed. Self-ratings of Tanner stage correlate well with direct observation (e.g., [26, 27]). For the two younger cohorts, early pubertal timing was defined as achieving Tanner stage IV (increased breast size and elevation) by age 12 (18.2% of females). These physical changes are highly salient to the girls themselves, their family, and their peers. The oldest cohort, however, was first interviewed at age 13. Thus, girls in this group who had already achieved Tanner stage IV or V could not be unambiguously assigned to a pubertal timing group using the Tanner staging method. Instead, these girls were classified as early maturers if they reported an onset of menarche before 11 years old. The proportion of early maturers identified this way was similar to the proportion identified using Tanner staging (15.7% vs. 18.2%). Together, 19.0% of females (unweighted N=115) were categorized as early maturers.

Adolescent and Young Adult Outcomes

Outcome status was derived by aggregating observations across two periods: adolescence (ages 13 to 16) and young adulthood (ages 19 and 21). All adolescent data except juvenile justice status was collected through parent and child interviews with the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment [25, 26]. Parent and adolescent report were combined using an either/or rule for adolescent outcomes unless otherwise specified. In young adulthood, all outcomes except officially recorded criminal offenses were assessed through participant interviews with the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment[27]. The timeframe for both interviews was the 3 months preceding the interview unless otherwise stated. Our goal was to assess a range of domains of functioning within each developmental period (e.g., crime, psychiatric functioning).

Crime

The following self/parent-report variables were used: 1) police contact (adolescence and young adulthood); 2) charge (adolescence only); and incarceration (young adulthood only). Offenses from NC administrative Offices of the Courts official juvenile and adult records were categorized as minor, moderate, or severe/violent(see [28] for definitions). Because there were few girls with severe/violent offenses, these were grouped with moderate offenses.

Psychiatric functioning and Substance Use

Scoring programs, written in SAS [29], combined information about the date of onset, duration, and intensity of each symptom to create diagnoses according to the DSM-IV. Two-week test-retest reliability of Child and Adolescent Assessment diagnoses in children aged 10 to 18 years is comparable to that of other highly structured interviews (Ks for individual disorders range from .56 to 1.0)[26]. Validity is well-established using multiple indices of construct validity[25]. All adolescent and young adult disorders with a 3-month prevalence greater than 1% were included. Three-month prevalence rates for ages 9 to 16 are available in [30].

School/Peers (adolescents only)

Truancy was coded if the child failed to reach, or left school at least twice, without the permission of the school authorities for reasons not associated with either separation anxiety or fear of school. Association with older peers was coded if the majority of the participant’s friends were two or more years older than his/her own age. Difficulty making friends was coded when the child reported difficulty forming or maintaining friendships. No best friend was coded when the child reported having no peer confidante. Finally, bullying peers was coded based upon the DSM-IV conduct disorder symptom.

Home (adolescents only)

High conflict with parents was coded if the number of reported parent-child arguments was in the top 25%. Poor sibling relations was coded if the participant reported high levels of conflictual interactions with any sibling. Running away and curfew violations were coded according to their DSM-IV descriptions for conduct disorder.

Sexual Behavior

Subjects reported whether they had ever had sexual intercourse, and, if so, the number of their sexual partners. Multiple sexual partners was defined by having 2 or more sexual partners in adolescence or 10 or more partners by young adulthood. Pregnancy was coded as positive, regardless of whether the fetus was carried to term. Sexually transmitted disease in young adulthood was coded if the participant reported testing positive for herpes, genital warts, chlamydia, or HIV. Young adults also reported whether any sexual encounter involved going home with a stranger.

Education/SES (young adults only)

School dropout was coded if the subject had not graduated from high school by age 21. Up to age 16, low occupational status was coded using the maximum of the parents’/subject’s occupational prestige as rated by the National Opinion Research Center/General Social Survey ratings. Thereafter, the maximum of the subject’s/subject’s spouse’s rating was used. Poverty status was coded based upon thresholds issued by the Census Bureau based on income and family size[31]. Material hardship was coded based upon the subject either being unable to meet basic needs, having no health insurance, financial problems, residential instability, or no insurance for mental health or substance abuse care.

Analyses

All associations were tested using weighted logistic regression models in a generalized estimating equations framework implemented by SAS PROC GENMOD. Robust variance (sandwich type) estimates were used to adjust the standard errors of the parameter estimates for the stratified design effects. Therefore, the parameters reported here are representative of the population from which the sample was drawn. Associations between early puberty status and each outcome were tested in adolescence (ages 13 to 16) and in young adulthood (ages 19 and 21).

Missing data

Across all waves, an average of 82% of possible interviews was completed, ranging from 75% to 94% at individual waves (Table 1). Three or four assessments (depending on the cohort) were possible in adolescence, and two assessments were possible in adulthood. If missing assessments was associated with pubertal timing, then our analyses might be biased. Pubertal timing, however, was not associated with missing assessments overall (odds ratio=0.6, 95%CI=0.4–1.1, p=.09) or in young adulthood only (odds ratio=0.6, 95%CI=0.4–1.2, p=.15). The overall statistical trend suggested that early maturers missed fewer assessments than their peers.

Results

Pubertal Timing and Adolescent Outcomes

Early maturation was associated with at least one indicator in each of the six adolescent outcome domains (11 of 26 specific indicators; see Table 2) and predicted having had any problems in substance use, school/peers, and psychiatric functioning domains (1 or more elevated indicators). The strongest associations (odds ratios > 3.0) were seen with substance use and conduct problems.

Table 2.

Early puberty and adolescent outcomes

| Physical Development | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | On-time | |||||||

| % | (SE) | % | (SE) | Dir | OR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Crime | ||||||||

| Minor | 7.5 | (4.1) | 5.4 | (1.4) | 1.4 | (0.4–5.1) | 0.60 | |

| Moderate | 1.0 | (0.6) | 2.9 | (1.1) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.4) | 0.13 | |

| Self-reported police contact | 21.0 | (6.3) | 11.7 | (2.1) | 2.0 | (0.9–4.6) | 0.11 | |

| Self-reported charge | 4.1 | (3.0) | 0.7 | (0.2) | ↑ | 5.7 | (1.1–30.3) | 0.03 |

| Any crime outcome | 20.4 | (6.1) | 14.7 | (2.3) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.4) | 0.34 | |

| Substance Use | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 7.0 | (4.2) | 1.2 | (0.7) | ↑ | 6.2 | (1.1–33.5) | 0.03 |

| THC abuse/dependence | 10.3 | (5.1) | 2.8 | (1.2) | ↑ | 3.9 | (1.0–15.2) | 0.04 |

| Illicit drub abuse/dependence | 10.4 | (5.1) | 1.5 | (0.7) | ↑ | 7.6 | (1.9–30.8) | <0.01 |

| Substance-related risky behavior | 6.2 | (4.2) | 0.3 | (0.2) | ↑ | 20.2 | (3.6–112.4) | <0.01 |

| Any substance outcome | 14.2 | (5.7) | 3.7 | (1.3) | ↑ | 4.2 | (1.3–13.6) | 0.02 |

| School/Peers | ||||||||

| Skipped school† | 25.2 | (6.7) | 15.5 | (2.6) | 1.8 | (0.8–4.1) | 0.13 | |

| Older Peers | 14.0 | (5.1) | 10.5 | (2.1) | 1.4 | (0.5–3.5) | 0.50 | |

| Difficulty making friends | 11.8 | (5.1) | 9.4 | (2.1) | 1.3 | (0.4–3.8) | 0.64 | |

| No best friend | 45.8 | (7.7) | 26.0 | (3.3) | ↑ | 2.4 | (1.2–4.8) | 0.01 |

| Bullies peers† | 4.1 | (3.1) | 1.5 | (0.8) | 2.8 | (0.4–18.0) | 0.29 | |

| Being bullied/teased | 16.7 | (5.7) | 9.1 | (1.8) | 2.0 | (0.8–5.0) | 0.13 | |

| Deviant peers* | 66.2 | (16.8) | 38.4 | (6.1) | 3.2 | (0.7–14.8) | 0.15 | |

| Any school/peer outcome | 63.7 | (7.3) | 45.8 | (3.8) | ↑ | 2.1 | (1.1–4.1) | 0.04 |

| Home | ||||||||

| High conflict with parent | 54.7 | (7.7) | 48.9 | (3.8) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.5) | 0.50 | |

| Poor sibling relations | 15.3 | (5.2) | 15.0 | (2.5) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.4) | 0.97 | |

| Runs away | 7.2 | (4.2) | 1.3 | (0.3) | ↑ | 6.1 | (1.6–23.6) | <0.01 |

| Stays out late | 1.6 | (0.7) | 1.6 | (0.7) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.4) | 0.97 | |

| Any home outcome | 59.7 | (7.6) | 54.4 | (3.8) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.5) | 0.54 | |

| Sexual Behavior | ||||||||

| Sexual intercourse | 33.8 | (7.2) | 19.6 | (2.8) | ↑ | 2.1 | (1.0–4.3) | 0.04 |

| Multiple sexual partners | 11.9 | (4.9) | 5.2 | (1.5) | 2.2 | (0.7–6.7) | 0.11 | |

| Pregnancy | 10.9 | (5.1) | 5.2 | (1.6) | 2.2 | (0.7–7.5) | 0.19 | |

| Any sexual outcomea | 19.7 | (6.2) | 10.5 | (2.2) | 2.1 | (0.9–5.2) | 0.11 | |

| Psychiatric Functioning | ||||||||

| Generalized Anxiety | 7.0 | (4.2) | 3.2 | (1.1) | 2.2 | (0.5–9.5) | 0.28 | |

| Depression | 17.1 | (6.1) | 7.2 | (1.8) | ↑ | 2.7 | (1.0–7.2) | 0.05 |

| Conduct Disorder | 8.0 | (4.3) | 2.1 | (0.7) | ↑ | 4.1 | (1.1–15.4) | 0.04 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 11.7 | (5.1) | 5.8 | (1.4) | 2.2 | (0.7–6.4) | 0.17 | |

| Any psychiatric outcome | 26.8 | (6.9) | 13.8 | (2.3) | ↑ | 2.3 | (1.0–5.0) | 0.04 |

Any sexual outcome group includes subjects reporting multiple sexual partners, pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases, but not those only reporting sexual intercourse only.

OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

Data only available on the oldest cohort

Symptoms of conduct disorder which is included as a separate outcome below

Pubertal Timing and Young Adult Outcomes

There were no significant associations between early maturation and any of the five young adult domains (see Table 3), suggesting that attenuation of the negative effects of early maturation was the rule. Only 3 of the 21 specific outcomes were significantly predicted by early puberty; these included higher rates of lifetime sexual partners, higher rates of young adult depression, and lower levels of illicit drug abuse. Depression was the only current young adult outcome for which early maturers were at increased risk. Depression in young adulthood might reasonably be related to psychiatric status in adolescence[32]. Testing associations with both disorders that were predicted by early puberty in adolescence – conduct disorder and depression – suggested that it was adolescent conduct disorder, not depression, that accounted for the higher rates of young adult depression. An interaction term between pubertal timing and adolescent conduct disorder significantly predicted young adult depression (odds ratio=221.8, 95%CI 9.7, 5094; p=.0007), such that 9% of early maturers with no history of adolescent conduct disorder displayed depression in young adulthood as compared to 81% of early maturers reporting a history of adolescent conduct disorder. After accounting for this interaction, the main effect of pubertal timing on young adult depression was no longer significant (odds ratio=1.9, 95%CI 0.5, 7.4; p=.38). Overall, there was little evidence of persistent, long-term effects of early pubertal timing, with the exception of a small group of girls at greater risk for depression in young adulthood.

Table 3.

Early puberty and young adulthood outcomes

| Physical Development | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | On-time | |||||||

| % | (SE) | % | (SE) | Dir | OR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Crime (16–21 years) | ||||||||

| Minor | 12.3 | (5.0) | 12.5 | (2.4) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.4) | 0.96 | |

| Moderate/Serious | 9.4 | (3.9) | 6.6 | (1.6) | 1.5 | (0.5–4.1) | 0.47 | |

| Self-reported police contact | 16.6 | (4.8) | 12.2 | (2.4) | 1.4 | (0.6–3.7) | 0.45 | |

| Self-reported incarceration | 0.3 | (0.3) | 0.3 | (0.1) | 1.1 | (0.1–10.6) | 0.92 | |

| Any crime outcome | 29.1 | (6.7) | 24.3 | (3.0) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.6) | 0.51 | |

| Substance Use | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 4.7 | (3.2) | 7.1 | (2.0) | 0.7 | (0.1–2.9) | 0.58 | |

| THC abuse/dependence | 4.3 | (3.2) | 4.4 | (1.6) | 1.0 | (0.2–5.3) | 0.99 | |

| Illicit drug abuse/dependence | 1.9 | (0.9) | 6.5 | (2.8) | ↓ | 0.3 | (0.1–0.8) | 0.02 |

| Any substance outcome | 9.4 | (4.4) | 11.6 | (2.4) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.4) | 0.69 | |

| Education/SES | ||||||||

| School dropout | 11.7 | (4.5) | 12.1 | (2.1) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.5) | 0.94 | |

| Low occupational Status | 39.8 | (7.7) | 33.5 | (3.7) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.7) | 0.46 | |

| Household in poverty | 67.0 | (7.3) | 64.3 | (3.8) | 1.1 | (0.6–2.3) | 0.75 | |

| Material Hardship | 59.7 | (7.7) | 45.9 | (3.9) | 1.7 | (0.8–3.3) | 0.14 | |

| Any education/employment outcome | 92.3 | (4.0) | 84.2 | (2.9) | 2.2 | (0.7–7.3) | 0.18 | |

| Sexual Behavior | ||||||||

| Going home with stranger | 6.4 | (4.3) | 3.9 | (1.6) | 1.7 | (0.3–8.6) | 0.55 | |

| Multiple sexual partners (>=10) | 3.1 | (2.9) | 0.3 | (0.1) | ↑ | 10.0 | (1.2–85.9) | 0.04 |

| Pregnancy | 29.8 | (6.8) | 34.5 | (3.6) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) | 0.55 | |

| Multiple pregnancies | 12.1 | (4.9) | 10.6 | (2.0) | 1.1 | (0.4–2.9) | 0.93 | |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 10.1 | (4.4) | 6.8 | (1.9) | 1.5 | (0.5–4.7) | 0.45 | |

| Any sexual outcome | 22.6 | (6.4) | 19.9 | (3.0) | 1.2 | (0.5–2.6) | 0.69 | |

| Psychiatric functioning | ||||||||

| Depressive Disorders | 15.2 | (5.9) | 5.1 | (1.5) | ↑ | 3.4 | (1.2–9.8) | 0.03 |

| Anxiety Disorders | 8.8 | (4.4) | 10.3 | (2.4) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.7) | 0.77 | |

| Generalized Anxiety | 7.4 | (4.3) | 3.9 | (1.6) | 2.0 | (0.5–8.8) | 0.37 | |

| Panic | 4.3 | (3.2) | 8.2 | (2.2) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.5) | 0.40 | |

| Agoraphobia | 4.4 | (3.2) | 4.2 | (1.6) | 1.1 | (0.2–5.6) | 0.95 | |

| Any psychiatric outcome | 17.6 | (5.9) | 18.0 | (3.0) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.4) | 0.95 | |

Antisocial personality disorder was excluded because of its low prevalence in females.

OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

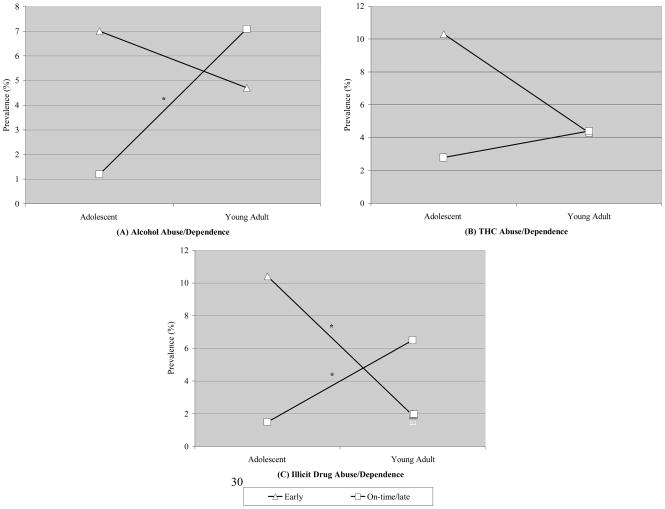

Attenuated effects of this kind might suggest either recovery by early maturers or “catch-up” by on-time/late maturers. Longitudinal analyses were conducted for indicators that were measured similarly across developmental periods (e.g., alcohol abuse/dependence, marijuana abuse/dependence, illicit drug abuse/dependence) to test whether they decreased from adolescent to young adulthood for early maturers (recovery) or increased across developmental periods for on-time/late maturers (catch-up). Figure 1 shows that early maturers recovered (i.e., decreased over time) in terms of their illicit drug abuse/dependence, whereas on-time/late peers caught up (i.e., increased over time) in their alcohol abuse/dependence. Neither the recovery nor the catch-up hypothesis was fully supported for marijuana abuse/dependence.

Figure 1.

Comparison of young adult and adolescent rates of outcomes with evidence of attenuation. Graphs compare rates for (a) alcohol abuse/dependence, (b) marijuana abuse/dependence, and (c) illicit drug abuse/dependence. Alcohol abuse/dependence increased for on-time/late maturers (odds ratio=6.3, 95%CI 1.8, 22.3; p=.005) did not significantly change for early maturers (odds ratio=0.7, 95%CI 0.1, 4.6; p=.67). Marijuana abuse/dependence did not differ significantly from adolescence to young adulthood for either early maturers (odds ratio=0.4, 95%CI 0.1, 2.6; p=.34) or on-time/late maturers (odds ratio=1.4, 95%CI 0.6, 3.3; p=.39). Illicit drug abuse/dependence decreases in early maturers (odds ratio=0.2, 95%CI 0.0, 0.7; p=.01) and increased in on-time/late maturers (odds ratio=4.6, 95%CI 1.5, 13.7; p=.007). * Indicates significant group difference.

Long-term Persistence in Select Groups

Despite the overall appearance of attenuation of the adolescent effects of early maturity in young adulthood, it is possible that adverse outcomes persisted for a subset of early maturers, such as those with the highest levels of adolescent problems. To test this hypothesis, we compared early maturers with elevated levels of negative outcomes in adolescence (upper 25%/>=5 on a cumulative negative outcome scale) to on-time maturers with similar levels of adolescent negative outcomes to determine whether early maturation predicts a more persistent course of disturbance. These groups were compared in terms of the total number of negative adult outcomes, as well as scales for total crime, substance, socioeconomic status, sexual behavior, and psychiatric outcomes. The most troubled adolescent early maturers did not differ from similarly troubled on-time maturers in terms of any adult outcomes (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of adult outcomes between highly-troubled adolescent groups

| Top 25% early maturers/>=5 adolescent outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | On-time | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean ratio | (95% CI) | P | |

| Crime outcomes | 0.4 | (0.7) | 0.5 | (0.6) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | 0.45 |

| Substance outcomes | 0.1 | (0.4) | 0.3 | (0.7) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.3) | 0.10 |

| Education/employment outcomes | 1.9 | (1.1) | 1.9 | (0.9) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.5) | 0.92 |

| Sexual outcomes | 1.5 | (1.3) | 1.5 | (0.8) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 0.91 |

| Psychiatric outcomes | 0.6 | (1.1) | 0.6 | (0.7) | 1.1 | (0.4–3.3) | 0.86 |

| Total adult outcomes | 4.5 | (2.1) | 4.7 | (0.2) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.3) | 0.75 |

Groups defined based upon the upper 25% for early maturers on a scale of total adolescent problems. This percentile corresponded to displaying 5 or more (upper 25%) adolescent outcomes. This cut-off included 31 early maturers and 109 on-time maturers. Mean ratios were derived from exponentiated standardized regression coefficients from Poisson regression. Mean ratios above 1.0 indicate higher levels in early maturing group. Similar results were obtained when looking at the top 50% of early maturers on total adolescent problems and those results are available from the first author by request.

SD=standard deviation; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

Finally, it is plausible that early maturers with particular types of adolescent problems are more likely to have persistent problems. In fact, this pattern was already observed for adolescent conduct disorder predicting young adult depression. To further test for this pattern, interaction terms between significant adolescent outcomes and pubertal timing were entered into models predicting each domain of young adult functioning as well as specific young adult psychiatric disorders. There was very little evidence that early maturation moderated the effect of adolescent indicators on young adult outcomes. Significant interactions occurred at the rate expected by chance and were equally likely to indicate decreased as increased risk for early maturers as compared to on-time/late maturers. Full results are available from the first author by request.

Discussion

Girls who developed early compared to their same-sex peers were at increased risk for negative status outcomes in adolescence, including running away, substance-related dangerous behavior, and sexual behavior as well as outcomes that are considered abnormal at any age such as depression, criminal charges, and illicit drug abuse. The strongest effects were seen for substance abuse, followed by conduct problems and finally more modest effects on emotional functioning. This pattern is similar to that in previous studies that looked at a range of adolescent outcomes (e.g., [4, 11]).

These negative effects, however, were mostly time-limited, with little evidence of continued problems into young adulthood. Attenuation of effects resulted from two concurrent processes: 1) recovery by early maturers (i.e., early maturers decreased their illicit drug abuse/dependence over time); and 2) catch-up by on-time/late maturers’ (i.e., on-time/late maturers increased in these outcomes over time). Early puberty ceased to be a risk factor for crime, substance, educational/employment, and most sexual outcomes in young adulthood (lifetime sexual partners being an important exception). Except for girls with adolescent conduct disorder, there was little evidence for the existence of subgroups of early maturers - identified by either severity or type of adolescent problems - that continued to have trouble in young adulthood.

Prior studies suggest few long-term effects of early pubertal timing on behavioral outcomes, however, there is less agreement on outcomes that endanger the successful transition to independence, such as poor educational attainment and early motherhood [5, 22, 23]. Our results suggest that long-term effects on such outcomes are modest at best. Stattin and Magnusson[15] only found long-term effects on post-secondary education levels and childbirth. In other areas of social support, personality, life values, and behavioral functioning (including delinquency, alcohol and substance use, smoking), few effects persisted. In our study, early developers displayed lower occupational status and more material hardship, but neither effect was statistically significant. Thus, even for outcomes related to transitioning to independence the effects of early maturation are time-limited and most persisting effects are modest. One exception to this rule in the current study was depression.

In a prior study, we reported little effect of pubertal timing on depression in adolescence in this sample[33]. That analysis, however, only included the first four waves of the study and two of three cohorts. The addition of 1345 adolescent observations (all cohorts followed through to age 16) changed our conclusion. Early maturers who also displayed the highest levels of behavior problems in adolescence were at greatest risk for depression in young adulthood, a sequence of mental health problems previously found for both males and females[34]. Thus, the effect of pubertal timing on depression in young adulthood may be most easily detectable in those with a history of adolescent conduct disorder.

Early maturers were also much more likely to report many sexual partners by young adulthood than their on-time/late maturing peers (a difference which was not significant in adolescence). A high number of lifetime sexual partners is linked with acquiring human papillomavirus infection[35], hepatitis C[36], and the human immunodeficiency virus[37], and thus poses a significant public health concern.

Strengths and Limitations

The Great Smoky Mountains study has several strengths besides its longitudinal, prospective design: The key variable, early puberty, was assessed yearly and prospectively for most girls from middle childhood through adolescence; A population-based design minimized selection biases; Finally, a wide range of functional domains in adolescence and young adulthood were assessed. The sample is not representative of the U.S. population (Native Americans overrepresented and African Americans and Latinos underrepresented). Also, the “gold standard” measure of pubertal development involves recurrent physical examinations by a medical professional. Such repeated intrusive assessment, however, would have been both financially prohibitive and might have lead to unacceptable sample attrition. Fortunately, there is adequate to good reliability between self/parent-reported physical development and official medical records[38]. As evidenced by the findings in adolescence, our pubertal measure was sufficiently sensitive to detect significant effects.

Conclusion

Although the short-term ill effects of early puberty are well-established, the question of whether early pubertal timing is sufficient to perturb normal functioning across subsequent developmental periods remains. The effects of most risk factors – even traumatic events – are generally time-limited (e.g., [39]). Early pubertal development represents a possible exception to this general rule because of its effects on social networks, its occurrence at a sensitive period in terms of educational functioning, proposed links to early sexuality and pregnancy, and gender-atypical elevation in conduct problems. Despite navigating a wide range of problems in adolescence, most early maturing females had levels of functioning similar to their same-sex peers by young adulthood. For a small group of early maturers, however, some troubles persisted close to a decade after beginning the pubertal transition. Fortunately, this group can be identified by their conduct problems in adolescence and perhaps provided the assistance necessary to avert long-term distress. Clinicians and public health policy professionals need only focus on a limited number of long-term outcomes for a limited number of early maturers.

References

- 1.Hayward C. International studies on child and adolescent health. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. cm; 2003. Gender differences at puberty. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burt SA, et al. Timing of menarche and the origins of conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):890–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: The sample case of girls at puberty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:157–168. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graber JA, et al. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(12):1768–1776. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stattin H, Magnusson D. Pubertal Maturation in Female Development. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obeidallah D, et al. Links between pubertal timing and neighborhood contexts: Implications for girls’ violent behavior. Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(12):1460–68. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142667.52062.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dick DM, et al. Pubertal timing and substance use: associations between and within families across late adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):180–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnusson D, Stattin H, Allen VL. Biological maturation and social development: A longitudinal study of some adjustment processes from mid-adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14:267–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02089234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prokopcakova A. Drug experimenting and pubertal maturation in girls. Studia Psychologica. 1998;40(4):287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaltiala-Heino R, Kosunen E, Rimpela M. Pubertal timing, sexual behaviour and self-reported depression in middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(5):531–45. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaltiala-Heino R, et al. Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(6):1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natsuaki MN, Biehl MC, Ge X. Trajectories of depressed mood from early adoelscence to young adulthood: The effects of pubertal timing and adoelscent dating. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19(1):47–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of Age Too Early: Pubertal Influences on Girls’ Vulnerability to Psychological Distress. Child Development. 1996;67(6):3386–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tschann JM, et al. Initiation of substance use in early adolescence: the roles of pubertal timing and emotional distress. Health Psychology. 1994;13:326–33. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stattin H, Magnusson D. Paths through Life - Volume 2: Pubertal Maturation in Female Development. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmons RG, Blyth DA. Moving into Adolescence: The Impact of Pubertal Change and School Context. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan PD, et al. The effects of pubertal timing on body image, school behavior and deviance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14(3):227–244. doi: 10.1007/BF02090320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubas JS, Graber JA, Petersen AC. The effects of pubertal development on achievement during adoelscence. American Journal of Education. 1991;99(4):444–460. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at grade 8. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4(1):125–144. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elder G, Caspi A. Human development and social change: An emerging perspective on the life course. In: Bolger N, Caspi A, editors. Persons in context: Developmental processes. Human development in cultural and historical contexts. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1988. pp. 77–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandler DP, Wilcox AJ, Horney LF. Age of menarche and subsequent reproductive events. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1984;119(5):765–774. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graber J, et al. Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):718–726. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000120022.14101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weichold K, Silbereisen R, Schmitt-Rodermund E. Short-term and long-tern consequences of early versus late physical maturation in adolescents. In: Hayward C, editor. Gender differences at puberty. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 241–276. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angold A, Costello E. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPAC) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:755–762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angold A, et al. The Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (YAPA) Duke University Medical Center; Durham, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copeland W, et al. Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: A prospective population-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1668–1675. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STATR Software: Version 9. SAS Institute, Inc; Cary, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalaker J, Naifah M. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports: Consumer Income. 1993. Poverty in the United States: 1997; pp. 60–201. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Copeland WE, et al. Childhood and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders as Predictors of Young Adult Disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM. Puberty and depression: The roles of age, pubertal status, and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim-Cohen J, et al. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen A, et al. Type-Specific HPV Infection and Multiple HPV Types: Prevalence and Risk Factor Profile in Nearly 12,000 Younger and Older Danish Women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35(3):276–282. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815ac5c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terrault N. Sexual activity as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36(5):S99–S105. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boily MC, et al. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2009;9(2):118–129. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris NM, Udry JR. Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1980;9:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02088471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandberg S, et al. Do high-threat life events really provoke the onset of psychiatric disorder in children? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:523–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]