Abstract

Aminoglycosides have been an essential component of the armamentarium in the treatment of life-threatening infections. Unfortunately, their efficacy has been reduced by the surge and dissemination of resistance. In some cases the levels of resistance reached the point that rendered them virtually useless. Among many known mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycosides, enzymatic modification is the most prevalent in the clinical setting. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes catalyze the modification at different −OH or −NH2 groups of the 2-deoxystreptamine nucleus or the sugar moieties and can be nucleotidyltranferases, phosphotransferases, or acetyltransferases. The number of aminoglycoside modifying enzymes identified to date as well as the genetic environments where the coding genes are located is impressive and there is virtually no bacteria that is unable to support enzymatic resistance to aminoglycosides. Aside from the development of new aminoglycosides refractory to as many as possible modifying enzymes there are currently two main strategies being pursued to overcome the action of aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Their successful development would extend the useful life of existing antibiotics that have proven effective in the treatment of infections. These strategies consist of the development of inhibitors of the enzymatic action or of the expression of the modifying enzymes.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, aminoglycoside, aminoglycoside modifying enzyme, acetyltransferase, nucleotidyltransferase, phosphotransferase, kinase, antisense, RNase P, RNase H, bacterial infection

1. A brief overview of aminoglycoside antibiotics

1.1. General aspects

Aminoglycoside antibiotics are a complex family of compounds characterized for having an aminocyclitol nucleus (streptamine, 2-deoxystreptamine, or streptidine) linked to amino sugars through glycosidic bonds. In addition, other compounds such as spectinomycin, which is an aminocyclitol not linked to amino sugars, or compounds that include the aminocyclitol fortamine are also included in this family (Bryskier, 2005; Veyssier and Bryskier, 2005). Aminoglycosides are primarily used in the treatment of infections caused by gram-negative aerobic bacilli, staphylococci, and other gram-positives (Yao and Moellering, 2007). However, when used against gram-positives, aminoglycosides are recommended in combination with other antibiotics such as β-lactams or vancomycin with which they exert a synergistic effect probably due to an enhanced uptake (Eliopoulos, 1989; Scaglione et al., 1995; Yao and Moellering, 2007). Due to the nature of the mechanism of uptake of aminoglycosides, which requires respiration, anaerobic bacteria are intrinsically resistant (see below) (Bryan et al., 1979). As it would be expected from a large family of non-identical compounds, different aminoglycosides vary in their activity spectrum. Streptomycin, discovered in 1943, was the first efficient drug against tuberculosis and in 1944 a woman with this disease was cured after treatment with the antibiotic. Currently, streptomycin is still used in combination therapy to treat Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Menzies et al., 2009) and other aminoglycosides such as amikacin or kanamycin are used as second line drug in the treatment of resistant M. tuberculosis infections (Brossier et al., 2010). Besides Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, examples of life-threatening infections that can be treated with aminoglycosides are plague, tularemia, brucellosis, endocarditis caused by enterococci and infections caused by streptococci and enterococci (Yao and Moellering, 2007). Newer non-traditional applications of aminoglycosides include treatment of genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis, in which about 10% of patients carry a nonsense mutation as opposed to the most common 3-bp deletion that results in the loss of a phenylalanine in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (Rich et al., 1990), and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, in which 10 - 20% of patients carry a nonsense mutation in the dystrophin gene (Kellermayer, 2006). The property of aminoglycosides to decrease the fidelity of the eukaryotic elongation machinery makes them potential candidates to treat nonsense mutation related genetic disorders such as those mentioned above or others that can benefit from inducing translational readthrough (Hermann, 2007; Kellermayer, 2006; Zingman et al., 2007). Aminoglycosides, mainly gentamicin, have also been used in the treatment of Ménière’s disease by intratympanic injection (Dabertrand et al., 2010; Nakashima et al., 2000). Aminoglycoside-based drugs are also inhibitors of reproduction of the HIV virus, showing promise on the treatment of AIDS (reviewed in Houghton et al., 2010)

The most common route of administration of aminoglycosides for systemic infections is parenteral, intramuscular injection or intravenously in cases of severe infections. Oral administration is not possible for these infections due to very low levels of absorption. However, oral administration can be used for decontamination purposes such as to kill bowel flora before intestinal surgery (Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003; Veyssier and Bryskier, 2005; Yao and Moellering, 2007). Other routes of delivery are sometimes used to increase the concentration of the drug at the site of infection or to limit nephrotoxicity or ototoxicity (Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003; Veyssier and Bryskier, 2005; Yao and Moellering, 2007). Aminoglycosides exist in a variety of formulations, some experimental, including encapsulation in liposomes or nanoparticles, or aerosolized (Dudley et al., 2008; Kingsley et al., 2006; Pinto-Alphandary et al., 2000). A study has shown that when amikacin-encapsulated liposomes were modified they changed the organ distribution of the antibiotic (Bucke et al., 1998). Aminoglycoside antibiotics are not metabolized, they are excreted as active compounds and they show biphasic elimination with half-lives in the body of 2 – 3 hours (as long as the renal function is normal) and 37 – 100 hours (Veyssier and Bryskier, 2005; Wenk et al., 1979). They are mainly eliminated by glomerular filtration.

Binding to serum proteins, although variable among different aminoglycosides, is low. While no serum binding was demonstrable for gentamicin, tobramycin, or kanamycin, streptomycin was found to be 35% bound in a comparative study (Gordon et al., 1972). Amikacin serum protein binding in patients with spinal cord injury and in able-bodied controls was ~18% (Brunnemann and Segal, 1991). The fraction bound to serum proteins is important because it is only the unbound fraction of a drug that produces a pharmacological effect (Benet and Hoener, 2002; Heinze and Holzgrabe, 2006).

The utilization of aminoglycosides is not free of adverse effects; they have been linked to drug-induced nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, a problem that limits the doses that can be used. Nephrotoxicity is generally reversible and the most common clinical presentation is nonoliguric acute kidney injury. Other manifestations include a decrease in the glomerular ! ltration rate, enzymuria, aminoaciduria, glycosuria, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hypokalemia (Martinez-Salgado et al., 2007; Oliveira et al., 2009). The ototoxicity effects of aminoglycosides include permanent bilaterally severe, high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss and temporary vestibular hypofunction (Guthrie, 2008). The mechanism by which aminoglycosides are ototoxic seems to be related to their ability to sequester and chelate metals forming complexes that are redox active and generate reactive oxygen species, which in turn induce cell damage (Guthrie, 2008). Free radical scavengers as well as iron chelators were shown to attenuate ototoxic effects of aminoglycosides (Nakashima et al., 2000).

1.2. Bacterial uptake

Internalization of aminoglycosides is an important process for their biological activity. Aminoglycosides penetrate the bacterial cell following a three-steps process; a first energy-independent step is followed by two energy-dependent steps (Taber et al., 1987; Tolmasky, 2007a; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003; Veyssier and Bryskier, 2005). Two components are needed for accumulation of aminoglycoside molecules inside the cell: ribosomes and the membrane bound respiratory chain. When aminoglycoside molecules are in contact with bacterial cells, the polycationic antibiotic molecules bind to cell’s surface anionic compounds such as lipopolysaccharide, phospholipids, and outer membrane proteins in gram-negatives, and teichoich acids and phospholipids in gram-positives. As a result of the binding to anionic sites in the outer membrane, divalent cations that cross-bridge adjacent lipopolysaccharide molecules are displaced resulting in an increase in permeability that leads to the so called “self-promoted uptake” penetration of aminoglycoside molecules to the periplasmic space (Vanhoof et al., 1995). The following process is blocked by inhibitors of electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation (Muir et al., 1984) and is known as “energy-dependent phase I”. Although alternatives have been proposed (Nichols and Young, 1985) it is generally accepted that this phase is characterized by the uptake into the cytoplasm of a small number of aminoglycoside molecules in an energy-dependent fashion, and since it needs a functional electron transport system anaerobes tend not to be susceptible to these antibiotics (Bryan and van der Elzen, 1977). The small number of molecules that reach the cytoplasm during energy-dependent phase I induce errors in protein synthesis and the mistranslated membrane proteins cause damage to the integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane when they are inserted triggering the following step known as “energy-dependent phase II”. This mechanism is supported by the need for protein synthesis for triggering the energy-dependent phase II (Hurwitz et al., 1981). The aberrant proteins in the damaged membrane facilitate transport of more molecules of antibiotic that increase the level of interference with normal protein synthesis leading to yet more damage in the membrane resulting in an autocatalytic accelerated rate of uptake that ultimately results in death of the cell (Davis, 1988; Nichols, 1989; Taber et al., 1987). The presence of capsule or exopolysaccharide layers seems not to affect diffusion of the aminoglycosides (Nichols et al., 1988).

1.3. Molecular mechanisms of action

Studies on the effect of aminoglycosides on protein synthesis resulted not only in an understanding of the mode of action of these antibiotics but also in contributions to the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of translation fidelity (Davies, 2006; Davis, 1987; Houghton et al.; Magnet and Blanchard, 2005; Majumder et al., 2007; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). It is clear now that pairing of the codon/anticodon nucleotides cannot account for the levels of fidelity observed in selection of the correct aminoacyl-tRNA (Ogle et al., 2001; Ogle et al., 2003). The ribosome plays an active role in stabilization of the cognate tRNA/mRNA association and rejection of near-cognate tRNAs. One of the earliest observations that led to the idea that the ribosome is an active player in the faithful decoding mechanism by modulating tRNA/mRNA interactions was the production of an enzyme that was otherwise absent due to a premature stop codon in specific Escherichia coli auxotrophic mutants upon addition of streptomycin (Spotts and Stanier, 1961). These experiments no only helped understanding mechanisms of translation fidelity during protein synthesis but also contributed to the clarification of the misreading-inducing properties of aminoglycosides. It is now well established that the A site is the decoding center of the ribosome, located on the 16S RNA (which together with about 21 proteins composes the 30S subunit of the ribosome). Regions of the 16S RNA establish contact with the cognate codon/anticodon pair and modify their structure resulting in what is known as the closed conformation of the 30S RNA subunit as opposed to the open structure of the empty A site (reviewed in Ogle et al., 2003; Ogle and Ramakrishnan, 2005; Zaher and Green, 2009). Conversely, binding of a near cognate tRNA does not induce the closed state.

The intimate mechanisms by which aminoglycosides interfere with translational fidelity are becoming ever more clear with the dilucidation of crystal structures of complexes between different aminoglycosides and the A site as well as the effects caused by these interactions. Structures of a number of aminoglycosides bound to oligonucleotides containing the decoding A site or the entire subunit have recently been determined by NMR or X-ray crystallography (reviewed in Jana and Deb, 2006; Ogle et al., 2003; Ogle and Ramakrishnan, 2005; Vicens and Westhof, 2003; Zaher and Green, 2009). These studies showed that not all classes of aminoglycosides bind to identical sites of the 16S rRNA but the common effect of their binding is a change of conformation of the A site to one that mimics the closed state induced by interaction between cognate tRNA and mRNA eliminating the proofreading capabilities of the ribosome and thereby promoting mistranslation. With the exception of spectinomycin and kasugamycin, aminoglycosides are bactericidal and their lethality is thought to be due to the secondary effects of inducing mistranslation (Bakker, 1992; Busse et al., 1992; Davis, 1987, 1989; Magnet and Blanchard, 2005; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003).

Aminoglycosides such as neomycin and paromomycin have also been shown to inhibit 30S ribosomal subunit assembly although this also could be a secondary effect to protein mistranslation (Mehta and Champney, 2003). Other effects of aminoglycosides include their ability to induce RNA cleavage (Belousoff et al., 2009) or interfere with essential functions such as RNase P, which has been shown to be inhibited by neomycin B due to interference of the antibiotic molecule with the binding of divalent metal ions to the RNA moiety of RNase P (Mikkelsen et al., 1999). These properties could be exploited to develop new aminoglycosides directed to targets other than the ribosome.

Experiments exposing E. coli cells to sublethal concentrations of amikacin showed that one of the most susceptible cellular mechanisms is formation of the Z ring, which leads to anomalies in cell division. At these low concentrations of the antibiotic the chromosomes continued replication and were properly located (Possoz et al., 2007).

2. Bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics

2.1. Mechanisms of resistance

Aminoglycoside resistance occurs through several mechanisms that can coexist simultaneously in the same cell (Alekshun and Levy, 2007; Houghton et al.; Magnet and Blanchard, 2005; Taber et al., 1987; Tolmasky, 2007a). Described mechanisms include modification of the target by mutation of the 16S rRNA or ribosomal proteins (Galimand et al., 2005; O’Connor et al., 1991); methylation of 16S rRNA, a mechanism found in most aminoglycoside-producing organisms and in clinical strains (Doi and Arakawa, 2007; Galimand et al., 2005); reduced permeability by modification of outer membrane’s permeability or diminished inner membrane transport (Hancock, 1981; MacLeod et al., 2000; Over et al., 2001); export outside the cell by active efflux pumps (Aires et al., 1999; Magnet et al., 2001; Rosenberg et al., 2000), one of which has recently been shown to be involved in adaptive resistance (Hocquet et al., 2003); active swarming, a probably non-specific mechanism recently shown in P. aeruginosa cells, which exhibited adaptive antibiotic resistance against several antibiotics (Overhage et al., 2008); sequestration of the drug by tight binding to an acetyltransferase of very low activity (Magnet et al., 2003); and enzymatic inactivation of the antibiotic molecule, the most prevalent in the clinical setting and the subject of this review.

3. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes

Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes catalyze the modification at −OH or −NH2 groups of the 2-deoxystreptamine nucleus or the sugar moieties and can be acetyltransferases (AACs), nucleotidyltranferases (ANTs), or phosphotransferases (APHs) (Fig. 1). The combination of mutagenesis, which leads to continuous generation of new enzyme variants that can utilize an ever growing number of antibiotics as substrates, with the coding genes’ ability to transfer at the molecular level as part of integrons, gene cassettes, transposons, or integrative conjugative elements and at the cellular level through conjugation, as part of mobilizable or conjugative plasmids, natural transformation or transduction results in the ability of this resistance mechanism to reach virtually all bacterial types (Tolmasky, 2007b).

Fig. 1.

Representative aminoglycosides and modification sites by AAC, ANT, and APH enzymes. An example of each kind of modification is shown on one of the substrates. The square and oval on positions 2′ and 6″ in paromomycin I indicate that although this molecule is preferentially acetylated at the position 1, 1,2′-di-N-acetylparomomycin and 1,6″-di-N-acetylparomomycin are also found as products of the enzymatic reaction (Sunada et al., 1999). AAC(3)-X can catalyze acetylation at the 3″-amino group in arbekacin and amikacin (Hotta et al. 1998).

The number of aminoglycoside modifying enzymes identified to date as well as the hosts and genetic environments is impressive, therefore the citations and examples described here should be considered representative rather than comprehensive. Furthermore, putative genes coding for aminoglycoside modifying enzymes are being found in complete genome sequences. These genes, for which there is no further information other than the annotation, are not discussed in this review. Summaries including relevant data on aminoglycoside modifying enzymes are shown in Fig. 1 and Tables 1 - 3.

Table 1.

Aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferases

| AACs | Gene names | Genetic location |

Accession number |

Host | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAC(1) |

E. coli, Actinomycete, Campylobacter spp. |

(Gomez-Luis et al., 1999; Lovering et al., 1987; Sunada et al., 1999) |

|||

| AAC(3)-Ia C |

aac(3)-Ia,

aacC1 |

Plasmid, transposon, integron |

X15852, AF550679 |

S. marcescens, E. coli,

Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, P. aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Proteus mirabilis |

(Javier Teran et al., 1991; Wohlleben et al., 1989) |

| AAC(3)-Ib | aac(3)-Ib | Integron | L06157 | P. aeruginosa | (Schwocho et al., 1995) |

| AAC(3)-Ic | aac(3)-Ic | Integron | AJ511268 | P. aeruginosa | (Riccio et al., 2003) |

| AAC(3)-Id | aac(3)-Id | Genomic island, integron |

AY458224 |

S. enterica, P. mirabilis,

Vibrio fluvialis |

(Doublet et al., 2004) |

| AAC(3)-Ie |

aac(3)-Ie,

aacCA5 |

Integron |

AY463797, DQ520937, AY463797 |

S. enterica, P. mirabilis,

P. aeruginosa |

(Gionechetti et al., 2008; Levings et al., 2005) |

| AAC(3)-IIa |

aac(3)-IIa,

aaC3, aacC5, aacC2, aac(3)-Va |

Plasmid | X13543 |

K. pneumoniae, E.

cloacae, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, S. typhimurium, Citrobacter freundii |

(Allmansberger et al., 1985) |

| AAC(3)-IIb |

aac(3)-IIb,

aac(3)-Vb |

M97172 |

E. coli, A. faecalis, S.

marcescens |

(Rather et al., 1992) (Dahmen et al., 2010) |

|

| AAC(3)-IIc |

aac(3)-IIc,

aacC2 |

Plasmid | X54723 | E. coli, P. aeruginosa | (Dubois et al., 2008) |

| AAC(3)-IIIa |

aac(3)-IIIa,

aacC3 |

Chromosome | X55652 | P. aeruginosa | (Vliegenthart et al., 1991a) |

| AAC(3)-IIIb | aac(3)-IIIb | L06160 | P. aeruginosa | ||

| AAC(3)-IIIc |

aac(3)-IIIc,

ant(2″)-Ib |

L06161 | P. aeruginosa | ||

| AAC(3)-IVa | aac(3)-IVa | Plasmid |

X01385, AY216678, AJ493432 |

E. coli, C. jejuni, P.

stutzeri |

(Brau et al., 1984; Heuer et al., 2002) |

| AAC(3)-VIa | aac(3)-VIa | Plasmid |

M88012, NC_009140 NC_009838 |

E. cloacae, S. enterica,

E. coli |

(Rather et al., 1993a) (Call et al., 2010) |

| AAC(3)-VIIa |

aac(3)-VIIa,

aacC7 |

Chromosome | M22999 | Streptomyces rimosus | (Lopez-Cabrera et al., 1989) |

| AAC(3)-VIIIa |

aac(3)-VIIIa,

aacC8 |

Chromosome | M55426 | Streptomyces fradiae | (Salauze et al., 1991) |

| AAC(3)-IXa |

aac(3)-IXa,

aacC9 |

Chromosome | M55427 | Micromonospora chalcea | (Salauze et al., 1991) |

| AAC(3)-X | aac(3)-Xa | Chromosome | AB028210 | Streptomyces griseus | (Ishikawa et al., 2000) |

| AAC(2′)-Ia | aac(2′)-Ia | Chromosome | L06156 | P. stuartii | (Rather et al., 1993b) |

| AAC(2′)-Ib | aac(2′)-Ib | Chromosome | CP001172 |

M. fortuitum, A.

baumannii |

(Adams et al., 2008; Ainsa et al., 1997) |

| AAC(2′)-Ic C | aac(2′)-Ic | Chromosome |

CP001658, NC_002945 |

M. tuberculosis, M. bovis | (Ainsa et al., 1997) |

| AAC(2′)-Id | aac(2′)-Id | Chromosome | NC_008596 | M. smegmatis | (Ainsa et al., 1997) |

| AAC(2′)-Ie | aac(2′)-Ie | Chromosome | M. leprae | (Ainsa et al., 1997) | |

| Putative AAC(2′) | Chromosome | AM743169 | S. maltophilia | (Crossman et al., 2008) | |

| AAC(6′)-Ia |

aac(6′)-Ia,

aacA1 |

Plasmid, transposon, integron |

M18967, AF047479, M86913 |

Citrobacter diversus, E.

coli, K. pneumoniae, Shigella sonnei |

(Tenover et al., 1988), (Parent and Roy, 1992) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib C |

aac(6′)-Ib, aac(6′)-4

aacA4 |

Plasmid, transposon, integron |

M21682, M23634, AF479774 |

K. pneumoniae, P.

mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, S. enterica, K. oxytoca, S. maltophilia, E. cloacae |

(Nobuta et al., 1988; Tran van Nhieu and Collatz, 1987) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib’ | aac(6′)-Ib’, aac(6′)-Ib6 | Integron |

L25617, AJ584652, L25666 |

P. fluorescens , P.

aeruginosa |

(Lambert et al., 1994b; Mendes et al., 2004); (Casin et al., 1998) |

| AAC(6′)-Ic | aac(6′)-Ic | Chromosome | M94066 | S. marcescens | (Shaw et al., 1992) |

| AAC(6′)-Ie |

aac(6′)-Ie, aac(6′)-bifuncional |

Transposon | M18086 |

S. aureus, Macrococcus

caseolyticus, E. faecalis, Enterococcus faecium |

(Rouch et al., 1987) |

| AAC(6′)-If | aac(6′)-If | Plasmid | X55353 | E. cloacae | (Teran et al., 1991) |

| AAC(6′)-Ig | aac(6′)-Ig | Chromosome | L09246 |

Acinetobacter

haemolyticus |

(Lambert et al., 1993) |

| AAC(6′)-Ih | aac(6′)-Ih | Plasmid | L29044 | A. baumannii | (Lambert et al., 1994a) |

| AAC(6′)-Ii C | aac(6′)-Ii | Chromosome | L12710 | Enterococcus spp. | (Costa et al., 1993; Draker et al., 2003; Wybenga-Groot et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Ij | aac(6′)-Ij | Chromosome | L29045 |

Acinetobacter

genomosp. 13 |

(Lambert et al., 1994a) |

| AAC(6′)-Ik | aac(6′)-Ik | Chromosome | L29510 | Acinetobacter sp. | (Rudant et al., 1994) |

| AAC(6′)-Ip |

aac(6′)-Il, aac(6′)-Im,

aac(6′)-Ip |

Integron | Z54241 | C. freundii | (Hannecart-Pokorni et al., 1997) |

| AAC(6′)-Iq | aac(6′)-Iq | Plasmid, integron |

AF047556 | K. pneumoniae | (Centron and Roy, 1998) |

| AAC(6′)-Im | aac(6′)-Im | Plasmid | AF337947 | E. coli, E. faecium | (Chow et al., 2001) |

| AAC(6′)-Il |

aac(6′)-Il,

aacA7 |

Plasmid, integron |

U13880 | Enterobacter aerogenes | (Bunny et al., 1995) |

| AAC(6′)-Ir | aac(6′)-Ir | Chromosome | AF031326 |

Acinetobacter

genomosp. 14 |

(Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Is | aac(6′)-Is | Chromosome | AF031327 |

Acinetobacter

genomosp. 15 |

(Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Isa | aac(6′)-Isa | Plasmid | AB116646 | Streptomyces albulus | (Hamano et al., 2004) |

| AAC(6′)-It | aac(6′)-It | Chromosome | AF031328 | A. genomosp. 16 | (Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Iu | aac(6′)-Iu | Chromosome | AF031329 | A. genomosp. 17 | (Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Iv | aac(6′)-Iv | Chromosome | AF031330 | Acinetobacter sp. | (Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Iw | aac(6′)-Iw | Chromosome | AF031331 | Acinetobacter sp. | (Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Ix | aac(6′)-Ix | Chromosome | AF031332 | Acinetobacter sp. | (Rudant et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Iy C | aac(6′)-Iy | Chromosome | AF144881 | S. enteritidis, S. enterica | (Magnet et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Iz | aac(6′)-Iz | Chromosome | AF140221 | S. maltophilia | (Lambert et al., 1999) |

| AAC(6′)-Iaa | aac(6′)-Iaa | Chromosome | NC_003197 | S. typhimurium | (Salipante and Hall, 2003) |

| AAC(6′)-Iad | aac(6′)-Iad | Plasmid | AB119105 |

Acinetobacter

genomosp. 3 |

(Doi et al., 2004) |

| AAC(6′)-Iae | aac(6′)-Iae | Integron | AB104852 |

P. aeruginosa, S.

enterica |

(Sekiguchi et al., 2005) |

| AAC(6′)-Iaf | aac(6′)-Iaf | Plasmid, integron |

AB462903 | P. aeruginosa | (Kitao et al., 2009) |

| AAC(6′)-Iai | aac(6′)-Iai | Plasmid, integron |

EU886977 | P. aeruginosa | |

| AAC(6′)-Ib3 | aac(6′)-Ib3, aac(6′)-Ib5 | integron | X60321 | P. aeruginosa | (Mabilat et al., 1992); (Casin et al., 1998) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib4 | aac(6′)-Ib4 | S49888 | Serratia spp. | (Toriya et al., 1992) | |

| AAC(6′)-Ib7 | aac(6′)-Ib7 | Plasmid | Y11946 | E. cloacae, C. freundii | (Casin et al., 1998), |

| AAC(6′)-Ib8 | aac(6′)-Ib8 | Plasmid | Y11947 | E. cloacae | (Casin et al., 1998) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib9 | aac(6′)-Ib9 | Integron | AF043381 | P. aeruginosa | (Mugnier et al., 1998a) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib10 | aac(6′)-Ib10 | Integron | P. aeruginosa | (Mugnier et al., 1998b) | |

| AAC(6′)-Ib11 C | aac(6′)-Ib11 | Integron | AY136758 | S. enterica | (Casin et al., 2003) |

| AAC(6′)-29a | aac(6′)-29a | Integron | AF263519 | P. aeruginosa | (Poirel et al., 2001) |

| AAC(6′)-29b | aac(6′)-29b | Integron | AF263520 | P. aeruginosa | (Poirel et al., 2001) |

| AAC(6′)-31 | aac(6′)-31 | Integron | AM28348, AM283490 |

Pseudomonas putida, A.

baumannii, K. pneumoniae |

(Mendes et al., 2007) |

| AAC(6′)-32 | aac(6′)-32 | Plasmid, integron |

EF614235 | P. aeruginosa | (Gutierrez et al., 2007) |

| AAC(6′)-33 | aac(6′)-33 | Integron | GQ337064 | P. aeruginosa | (Viedma et al., 2009) |

| AAC(6′)-I30 | aac(6′)-I30 | Integron | AY289608 | S. enterica | (Mulvey et al., 2004) |

| AAC(6′)-Iid | aac(6′)-Iid | Chrosmome | AJ584700 | Enterococcus durans | (Del Campo et al., 2005) |

| AAC(6′)-Iih | aac(6′)-Iih | Chromosome | AJ584701 | Enterococcus hirae | (Del Campo et al., 2005) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib-Suzhou | aac(6′)-Ib-Suzhou | EF37562, EU085533 |

E. cloacae, K.

pneumoniae |

(Huang et al., 2008) | |

| AAC(6′)-Ib-Hangzhou | aac(6′)-Ib-Hangzhou | FJ503047 | A. baumannii | ||

| AAC(6′)-SK | aac(6′)-sk | Chromosome | AB164230 |

Streptomyces

kanamyceticus |

(Matsuhashi et al., 1985) |

| AAC(6′)-IIa | aac(6′)-IIa | Plasmid, integron |

M29695 |

P. aeruginosa, S.

enterica |

(Shaw et al., 1989) |

| AAC(6′)-IIb | aac(6′)-Iib | Integron | L06163 | P. fluorescens | |

| AAC(6′)-IIc | aac(6′)-IIc | Plasmid, integron |

NC_012555 | E. cloacae | (Chen et al., 2009) |

| AAC(6′)-Ib-cr | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | Plasmid, transposon, integron |

DQ303918 | Enterobacteriaceae | (Robicsek et al., 2006) |

| AAC(6′)-Ie-APH(2″)-Ia | aac(6′)-aph (2″) | Plasmid, transposon |

M18086, M13771 |

S.aureus, E. faecalis, E.

faecium, Staphylococcus. warneri |

(Rouch et al., 1987) |

| ANT(3″)-Ii-AAC(6′)-IId |

ant(3″)-Ii-aac(6′)-IId,

ant(3″)-Ih-aac(6′)-IId |

Integron | AF453998 | S. marcescens | (Centron and Roy, 2002) |

| AAC(6′)-30/AAC(6′)-Ib’ | aac(6′)-30/aac(6′)-Ib’ | Integron | AJ584652 | P. aeruginosa | (Mendes et al., 2004) |

| AAC(3)-Ib/AAC(6′)-Ib” | aac(3)-Ib/aac(6′)-Ib” | Integron | AF355189 | P. aeruginosa | (Dubois et al., 2002) |

Only representative hosts, references and accession numbers are shown.

C, three dimensional structure has been resolved. AAC(3)-Ia pdb id: 1BO4 (Wolf et al., 1998). AAC(2′)-Ic pdb id: 1M44, 1M4D (in complex with CoA and tobramycin), 1M4G (in complex with CoA and ribostamycin), 1M4I (in complex with CoA and kanamycin A) (Vetting et al., 2002). AAC(6′)-Ib pdb id: 1V0C (in complex with kanamycin C and AcetylCoA), 2BUE (in complex with ribostamycin and CoA), 2VQY (in complex with parmomycin and AcetylCoA (Vetting et al., 2008); 2PRB (in complex with CoA), 2QIR (in complex with CoA and kanamycin) (Maurice et al., 2008). AAC(6′)-Ib11 pdb id: 2PR8 (Maurice et al., 2008). AAC(6′)-Ii pdb id: 2A4N (in complex with CoA) (Burk et al., 2005), 1N71 (in complex with CoA) (Burk et al., 2003), 1B87 (in complex with AcetylCoA) (Wybenga-Groot et al., 1999). AAC(6′)-Iy pdb id: 2VBQ (in complex with bisubstrate analog CoA-S-monomethy-acetylneamine) (Magalhaes et al., 2008), 1S3Z (in complex with CoA and ribostamycin), 1S5K (in complex with CoA and N-terminal His(6)-tag, crystal form 1), 1S60 (in complex with CoA and N-terminal His(6)-tag, crystal form 2) (Vetting et al., 2004).

Table 3.

Aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferases

| APHs | gene names | Genetic location |

Accesion number |

Host | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APH(4)-Ia | aph(4)-Ia, hph | Plasmid | V01499 | E. coli | (Kaster et al., 1983) |

| APH(4)-Ib | aph(4)-Ib, hyg | Chromosome | X03615 |

Streptomyces

hygroscopicus |

(Zalacain et al., 1986) |

| APH(6)-Ia | aph(6)-Ia, aphD, strA | Chromosome | Y00459 | S. griseus | (Distler et al., 1987) |

| APH(6)-Ib | aph(6)-Ib, sph | Chromosome | X05648 | S. glaucescens | (Vogtli and Hutter, 1987) |

| APH(6)-Ic | aph(6)-Ic, str | Transposon | X01702 |

S. enterica, P.

aeruginosa, E. coli |

(Mazodier et al., 1985; Steiniger-White et al., 2004) |

| APH(6)-Id | aph(6)-Id, strB, orfI | Plasmid, integrative conjugative element, chromosomal genomic islands |

M28829 |

K. pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., E. coli, Shigella flexneri, Providencia alcalifaciens, Pseudomonas spp., V. cholerae, Edwardsiella tarda, Pasteurella multocida, Aeromonas bestiarum |

(Daly et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2008; Meyer, 2009; Scholz et al., 1989) |

| APH(9)-Ia C | aph(9)-Ia | Chromosome |

U94857, CR628337 |

L. pneumophila | (Suter et al., 1997) |

| APH(9)-Ib | aph(9)-Ib, spcN | Chromosome | U70376 | S. flavopersicus | (Lyutzkanova et al., 1997) |

| APH(3′)-Ia | aph(3′)-Ia, aphA-1 | Transposon | V00359 | E. coli, S. enterica | (Oka et al., 1981) |

| APH(3′)-Ib | aph(3′)-Ib, aphA-like | Plasmid | M20305 | E. coli | (Pansegrau et al., 1987) |

| APH(3′)-Ic |

aph(3′)-Ic, apha1-1AB,

apha7 |

Plasmid, transposon, genomic island |

M37910 |

K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, S. marcescens, Corynebacterium spp., Photobacterium spp., Citrobacter spp. |

(Lee et al., 1990; Tauch et al., 2000) |

| APH(3′)-IIa C | aph(3′)-Iia, aphA-2 | Transposon | V00618 | E. coli | (Beck et al., 1982) |

| APH(3′)-IIb | aph(3′)-IIb | Chromosome | NC_002516 | P. aeruginosa | (Stover et al., 2000) |

| APH(3′)-IIc | aph(3′)-IIc | Chromosome | S. maltophilia | (Okazaki and Avison, 2007) | |

| APH(3′)-IIIa C | aph(3′)-IIIa | Plasmid | V01547 |

S. aureus, Enterococcus spp. |

(Trieu-Cuot and Courvalin, 1983) |

| APH(3′)-IVa | aph(3′)-Iva, aphA4 | Chromosome | X01986 | B. circulans | (Herbert et al., 1983) |

| APH(3′)-Va | aph(3′)-Va, aphA-5a | Chromosome | K00432 | Streptomyces fradiae | (Thompson and Gray, 1983) |

| APH(3′)-Vb | aph(3′)-Vb, aphA-5b, rph | Chromosome | M22126 |

Streptomyces

ribosidificus |

(Hoshiko et al., 1988) |

| APH(3′)-Vc | aph(3′)-Vc, aphA-5c | Chromosome | S81599 | M. chalcea | (Salauze et al., 1991) |

| APH(3′)-VIa | aph(3′)-Via, aphA-6 | Plasmid | X07753 | A. baumannii | (Martin et al., 1988) |

| APH(3′)-VIb | aph(3′)-VIb | Plasmid |

K. pneumoniae, S.

marcescens |

(Gaynes et al., 1988) | |

| APH(3′)-VIIa | aph(3′)-VIIa, aphA-7 | Plasmid | M29953 | C. jejuni | (Tenover et al., 1989) |

| APH(2″)-Ia |

aph(2″)-Ia, aph(2″)-

bifunctional |

Plasmid | AP003367 |

S. aureus, Clostridium

difficile, Streptococcus mitis, E. faecium |

(Ferretti et al., 1986) |

| APH(2″)-IIa C | aph(2″)-Iia, aph(2′)-Ib | Chromosome |

AF207840, AF337947 |

E. faecium, E. coli | (Kao et al., 2000) |

| APH(2″)-IIIa C | aph(2″)-IIIa, aph(2′)-Ic | Plasmid | U51479 |

Enterococcus

gallinarum |

(Chow et al., 1997) |

| APH(2″)-IVa C | aph(2″)-Iva, aph(2″)-Id | Chromosome | AF016483 | E. casseliflavus | (Tsai et al., 1998) |

| APH(2″)-Ie | aph(2″)-Ie | Plasmid, transposon |

AY939911 |

E. faecium , E.

casseliflavus |

(Chen et al., 2006) |

| APH(3″)-Ia | aph(3″)-Ia, aphE, aphD2 | Chromosome | X53527 | S. griseus | (Trower and Clark, 1990) |

| APH(3″)-Ib | aph(3″)-Ib, strA, orfH | Plasmid, transposon, integrative conjugative elements, chromosome |

M28829 |

Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp. |

(Scholz et al., 1989) |

| APH(3″)-Ic | aph(3″)-Ic | Chromosome | DQ336355 | M. fortuitum | (Ramon-Garcia et al., 2006) |

| APH(7″)-Ia | aph(7″)-Ia, aph7! | Chromosome | S. hygroscopicus | (Berthold et al., 2002) |

Only representative hosts, references and accession numbers are shown.

C, three dimensional structure has been resolved. APH(9)-Ia pdb id: 3I0O (in complex with ADP and Spectinomcyin), 3I0Q (in complex with AMP), 3I1A (Fong et al., 2010). APH(3′)-IIa pdb id: 1ND4 (Nurizzo et al., 2003). APH(3′)-IIIa pdb id: 1J7I, 1J7L (in complex with ADP), 1J7U (in comlex with APPNP) (Burk et al., 2001), 1L8T (in complex with ADP and kanamycin A) (Fong and Berghuis, 2002) 3H8P (in complex with AMPPNP and butirosin A) (Fong and Berghuis, 2009), 2BKK (in complex with the inhibitor AR_3A) (Kohl et al., 2005). APH(2″)-IIa pdb id: 3HAV (in complex with ATP and streptomycin), 3HAM (in complex with gentamicin) (Young et al., 2009).

3.1. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes: nomenclature

There are two main nomenclatures currently in use to identify aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. One of them consists of a three-letter identifier of the activity followed by the site of modification between parenthesis (class), a roman number particular to the resistant profile they confer to the host cells (subclass), and a low case letter that is an individual identifier (Shaw et al., 1993). The parenthesis and the subclass are usually separated by a hyphen but lately some authors have removed it (Oteo et al., 2006). For example, AAC(6′)-Ia represents an N-acetyltransferase that catalyzes acetylation at the 6′ position conferring a resistance profile identical to the other AAC(6′)-I enzymes (AAC(6′)-Ib – AAC(6′)-Iaf). In the other nomenclature system the genes are designated aac, aad and aph followed by a capital letter that identifies the site of modification (Novick et al., 1976). Thus, aacA, aacB, and aacC identify aminoglycoside 6′-N- acetyltransferase, aminoglycoside 2′-N- acetyltransferase, and aminoglycoside 3-N-acetyltransferase respectively. A number is then added to provide a unique identifier to different genes. Each of the nomenclatures has its own advantages and disadvantages and different authors prefer one to the other but, as it has been suggested before (Tolmasky, 2007a; Vanhoof et al., 1998), it would be convenient to reach consensus and use only one of them to avoid confusion and facilitate following the advances in the field. The confusion is sometimes compounded by different additions or modifications in naming new genes or variants (see below). We suggest that returning to a simpler nomenclature with the support of an internet repository site could facilitate the naming of the genes, avoid duplications, and facilitate further changes when new enzymes with new, and may be unexpected, characteristics are discovered.

3.2. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes: aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferases (AACs)

AACs belong to the ubiquitous GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) superfamily of proteins, which include about 10,000 proteins (Vetting et al., 2005). GNAT enzymes catalyze the acetylation of −NH2 groups in the acceptor molecule using acetyl coenzyme A as donor substrate, in the case of AACs the acceptor is an aminoglycoside antibiotic. The AACs catalyze acetylation at the 1 [AAC(1)], 3 [AAC(3)], 2′ [AAC(2′)], or 6′ [AAC(6′)] positions (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The three dimensional structures of several acetyltransefrases have been resolved (see Table 1), mechanistic and structural aspects of these and other representatives of these enzymes have been thoroughly studied and reviewed (Azucena and Mobashery, 2001; Houghton et al., 2010; Tolmasky, 2007a; Vetting et al., 2005; Wright and Berghuis, 2007).

3.2.1. AAC(1)

To date AAC(1) enzymes have been found in E. coli , Campylobacter spp., and an actinomycete (Gomez-Luis et al., 1999; Lovering et al., 1987; Sunada et al., 1999). The AAC(1) isolated from E. coli catalyzes acetylation of apramycin, butirosin, lividomycin and paromomycin at the 1 position, and catalyzes di-acetylation of ribostamycin and neomycin. The AAC(1) isolated from an actinomycete (strain #8) differed in substrate profile from that one from E. coli as apramycin was not acetylated by this enzyme. Furthermore paromomycin was preferentially acetylated at position 1, but 1,2′-di-N-acetylparomomycin and 1,6″′-di-N-acetylparomomycin were also found as products of the enzymatic reaction (Sunada et al., 1999). These studies also determined that these modifications were not accompanied by a significant reduction of the antibiotic activity. The substrate profile of the AAC(1) isolated from Campylobacter spp. was similar to that of the E. coli enzyme. This was the only instance in which an AAC(1) was found in clinical isolates. The authors suggested that the gene is located in the chromosome, but these results await confirmation. Although all three enzymes have been named AAC(1), the difference in substrate profile of at least one of them would justify to named them with a subclass number.

3.2.2. AAC(3)

There are nine recognized subclasses of AAC(3) enzymes described to date, all of them in gram-negatives. The subclass AAC(3)-V has been eliminated after confirmation that the only enzyme in this group is identical to AAC(3)-II (Shaw et al., 1993). The subclass AAC(3)-I includes five enzymes that confer resistance to gentamicin, sisomicin, and fortimicin (astromicin) and are present in a large number of Enterobacteriaceae and other gram-negative clinical isolates. The X-ray structure of AAC(3)-Ia from Serratia marcescens (Javier Teran et al., 1991) complexed to CoA has been determined at 2.3 Å resolution (Wolf et al., 1998), as it is the case with several acetyltransferases this enzyme seems to exist as a dimer under physiological conditions.

All five genes have been found as part of gene cassettes in integrons. The latest gene in this subclass to be reported is aac(3)-Ie, which was found in integrons in Proteus vulgaris, P. aeruginosa, and within a Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica genomic island (Gionechetti et al., 2008; Wilson and Hall, 2010).

The subclass AAC(3)-II, which is characterized by resistance to gentamicin, netilmicin, tobramycin, sisomicin, 2′-N-ethylnetilmicin, 6′-N-ethylnetilmicin and dibekacin (Shaw et al., 1993), includes three enzymes: AAC(3)-IIa and AAC(3)-IIb, which were previously published as AAC(3)-Va and AAC(3)-Vb (see letter and reply van de Klundert and Vliegenthart, 1993), and AAC(3)-IIc. While AAC(3)-IIa has been found in a large variety of genera, AAC(3)-IIb and AAC(3)-IIc have been found in E. coli, Alcaligenes faecalis and S. marcescens or E. coli and P. aeruginosa respectively (Dubois et al., 2006; Dubois et al., 2008; Oteo et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 1993). A recent survey of Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates from a Tunisian Hospital showed the presence of undetermined AAC(3)-II enzymes, although the authors suggest the possibility of AAC(3)-IIb, in all genera tested (Dahmen et al., 2010).

There are three enzymes belonging to the subclass AAC(3)-III, all isolated from P. aeruginosa isolates. When cloned, the aac(3)-IIIa gene was expressed in P. aeruginosa but not in E. coli (Vliegenthart et al., 1991b). This does not seem to be due to an inactive promoter in E. coli. The authors proposed that most probably the mRNA is not completely synthesized or the initiation of translation of the gene is obstructed (Vliegenthart et al., 1991b). There were other early reports of AAC(3)-III enzymes in other genera, e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae, but they seem to be misnamed (for clarification see Vliegenthart et al., 1991b).

The only representative of AAC(3)-IV has been identified in clinical strains of E. coli (originally thought to be Salmonella) (Brau et al., 1984), Campylobacter jejuni, and in environmental Pseudomonas stutzeri (Heuer et al., 2002).

Although only AAC(3)-VIa is recognized in the literature within subclass AAC(3)-VI, comparison of the original sequence from Enterobacter cloacae, with the more recently isolated genes from E. coli, and S. enterica show a one amino acid difference (Call et al., 2010; Rather et al., 1993a).

Subclasses AAC(3)-VII, AAC(3)-VIII, AAC(3)-IX, and AAC(3)-X are represented in strains of actinomycetes (Ishikawa et al., 2000; Lopez-Cabrera et al., 1989; Salauze et al., 1991). This latter enzyme was of interest because besides catalyzing acetylation of kanamycin and dibekacin at the 3-amino group it also mediates acetylation the 3″-amino group in arbekacin and amikacin, making this the first AAC detected to have also AAC(3″) activity. Interestingly, while 3″-N-acetylamikacin lost most or all antibiotic activity, 3″-N-acetylarbekacin was still active (Hotta et al., 1998).

3.2.3. AAC(2′)

These enzymes have been found in gram-negatives and Mycobacterium, they mediate modification of several aminoglycosides including gentamicin, tobramycin, dibekacin, kanamycin and netimicin. Only one subclass exists, which includes AAC(2′)-Ia (Providencia stuartii), AAC(2′)-Ib (Mycobacterium fortuitum and Acinetobacter baumannii), AAC(2′)-Ic (M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis), AAC(2′)-Id (Mycobacterium smegmatis), and a putative AAC(2′)-Ie identified in the Mycobacterium leprae genome (Adams et al., 2008; Ainsa et al., 1997; Hegde et al. 2001; Rather et al., 1993b). A putative AAC(2′) enzyme has been proposed to be part of multidrug resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia but it has not been named further (Crossman et al., 2008). Our Blast analysis of the amino acid sequence of this protein against those in GenBank did not show 100% homology with any of the AAC(2′) know enzymes.

3.2.4. AAC(6′)

AAC(6′) enzymes are by far the most common, they are present in gram-negatives as well as gram-positives, the genes have been found in plasmids and chromosomes, and are often part of mobile genetic elements, some of them with unusual structures (Centron and Roy, 2002; Soler Bistue et al., 2008; Tolmasky, 2007a; Tolmasky, 2000). Accordingly, there is a very large volume of information available about them. There are two main subclasses of AAC(6′) enzymes that specify resistance to several aminoglycosides and differ in their activity against amikacin and gentamicin C1. While AAC(6′)-I shows high activity against amikacin and gentamicin C1a and C2 but very low towards gentamicin C1, AAC(6′)-II enzymes actively mediate acetylation of all three forms of gentamicin but not amikacin (Rather et al., 1992; Shaw et al., 1993; Tolmasky, 2007a; Tolmasky et al., 1986; Woloj et al., 1986). A novel enzyme that includes fluoroquinolones as substrates, could be considered a third class because of the change in pattern of substrates but it has been named AAC(6′)-Ib-cr, most probably because it is an evolutionary product of AAC(6′)-Ib by modification of two amino acids, Trp102Arg and Asp179Tyr (Robicsek et al., 2006). Unfortunately, due to the high variability and number of enzymes belonging to this class, the fast pace of research on these enzymes, and the fact that a large number of enzymes have different degrees of similarity in sequence and phenotype, there is a good deal of confusion and lack of consistency in nomenclature and classification of many members. In at least one instance two simultaneously discovered enzymes were named identically (Vanhoof et al., 1998). Enzymes with AAC(6′)-II resistance profiles but with higher identity to AAC(6′)-I enzymes at the amino acid level were named AAC(6′)-I (Casin et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 1994b). Different enzymes have been named identically, for example an acetyltransferase encoded by plasmid pBWH301 was named AAC(6′)-Il (accession number U13880) (Bunny et al., 1995), and the same name was used to name an acetyltransferase from C. freundii Cf155 (accession number Z54241) (Hannecart-Pokorni et al., 1997). This latter enzyme was subsequently renamed AAC(6′)-Im (Vanhoof et al., 1998). A search in PubMed shows the title of this paper as “AAC(6′)-Im [corrected]”. However, this enzyme was also called AAC(6′)-Ip by Centrón et al (Centron and Roy, 1998). Another enzyme identified later in E. coli and Entererococcus faecium was named AAC(6′)-Im (Chow et al., 2001).

The AAC(6′)-I subclass is so highly populated that a double low case letter was necessary to identified them, at the moment the latest published enzyme named as such is the AAC(6′)-Iaf (Kitao et al., 2009). An AAC(6′)-Iai can be found in GenBank but not AAC(6′)-Iag or AAC(6′)-Iah. Variants of AAC(6′)-Ib have been identified with subscripts e.g., AAC(6′)-Ib3, AAC(6′)-Ib4, AAC(6′)-Ib6, and AAC(6′)-Ib7 and differ at the N-terminus but have similar behavior (Casin et al., 1998). Conversely variant AAC(6′)-Ib11, found in a class 1 integron in S. Typhimurium, exhibits a two amino acids difference with AAC(6′)-Ib at positions 118 and 119 that results in an extended resistance spectrum that would merit the definition of a new subclass (Casin et al., 2003). Another variation to the nomenclature used only once is the addition of a prime symbol. The Pseudomonas fluorescens BM2687 AAC(6′)-Ib’ is encoded by a gene that has a Ser instead of a Leu residue at position 90, a substitution previously recognized as responsible for changing the resistance profile from subclass I to II (Lambert et al., 1994b; Rather et al., 1992). Besides the addition of a prime symbol, the name of this enzyme is also unusual, although not unique, in that in spite of having a AAC(6′)-II phenotype is called as if belonging to subclass AAC(6′)-I. AAC(6′)-Ib’ also exist as a fusion protein with a nucleotidyltransferase identified as ANT(3″)-Ii/AAC(6′)-IId in a S. marcescens integron that includes a group II intron (Centron and Roy, 2002). Considering the total identity between AAC(6′)-IId portion of the S. marcescens enzyme and AAC(6′)-Ib’, the name of this latter enzyme should be changed to AAC(6′)-IId. Other modifications to the nomenclature include removal of the roman number that identifies the subclass and the addition of a number, e.g. AAC(6′)-29a, AAC(6′)-29b, AAC(6′)-31, AAC(6′)-32, or AAC(6′)-33 (Gutierrez et al., 2007; Mendes et al., 2007; Poirel et al., 2001; Viedma et al., 2009); or the substitution of the low case letter for a number as in the S. enterica AAC(6′)-I30 enzyme (Mulvey et al., 2004). Other recent variations to the nomenclature consist on the addition of whole words or acronyms such as AAC(6′)-Ib-Suzhou (Huang et al., 2008) or AAC(6′)-Isa (Hamano et al., 2004). The monumental number of identified genes together with the de facto lack of a unified and agreed nomenclature for AAC(6′) enzymes make it extremely difficult to get a clear nomenclature landscape about these enzymes. The AAC(6′)-Id protein has been mentioned several times in the literature, but the accession number provided (X12618) does not currently correspond to an acetyltransferase and for that reason it has not been included in Table 1.

AAC(6′) enzymes can exist as fusion proteins occupying the N or C terminal region of the composite protein (Zhang et al., 2009). These fused aac(6′) genes are usually found within integrons and they can be the result of integrase-mediated recombination events (Centron and Roy, 2002). Interestingly, proteins containing AAC(6′)-I activities have been found fused to APH, ANT, a different AAC, and another AAC(6′)-I activities. AAC(6′)-Ie is located to the amino terminal end of a bifunctional Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus enzyme with AAC(6′) and APH(2″) activities (Boehr et al., 2004; Ferretti et al., 1986). The aac(6′)-aph(2″) gene is usually present in Tn4001-like transposons (Culebras and Martinez, 1999). As described above, the AAC(6′)-IId is the carboxy terminal region of the protein fusion that also includes an ANT(3″)-I activity. Fusions of two AAC(6′)-I activities, AAC(6′)-30/AAC(6′)-Ib’, or two AAC belonging to different subclasses, AAC(3)-Ib and AAC(6′)-Ib’ were found in P. aeruginosa integrons (Dubois et al., 2002; Mendes et al., 2004).

Three phylogenetic subgroups have been recognized among AAC(6′)-I and AAC(6′)-II enzymes (Hannecart-Pokorni et al., 1997; Shaw et al., 1993; Shmara et al., 2001) but an alternative theory has been published that proposes that the three groups are less related than thought before and the 6′ acetylating activity has evolved independently at least three times (Salipante and Hall, 2003).

An immunochromatographic method based on the utilization of monoclonal antibodies against the AAC(6′)-Iae has recently been reported (Kitao et al., 2010). This enzyme was selected for these studies because aac(6′)-Iae is prevalent in Japan and appears linked to the metallo-!-lactamase gene blaIMP and ant(3″)-Ia in the integron In113, making the assay a useful tool to detect multiple drug resistance in P. aeruginosa in this country (Kitao et al., 2010). However, 37% of the negative isolates from Japan still showed a multiple drug resistance phenotype and 76% of these negative isolates include aac(6′)-Ib and the metallo-!-lactamase gene blaIMP-1. At present, the authors of this study are developing an immunochromatography assay targeting AAC(6′)-Ib and metallo-!-lactamase IMP to complement that one targeting AAC(6′)-Iae for a more complete diagnostics tool (Kitao et al., 2010).

AAC(6′)-Ib is probably the most clinically relevant acetyltransferase and is responsible for the resistance to amikacin and other aminoglycosides found in several gram-negatives belonging to the genus Acinetobacter and to the Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Vibrionaceae (reviewed in Tolmasky, 2007a; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). It is present in over 70% of AAC(6′)-I-producing gram-negative clinical isolates (Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003) and, as mentioned above, some of its variants show an extended spectrum including resistance to gentamicin [AAC(6′)-Ib11] (Casin et al., 2003) or reduced susceptibility to quinolones [AAC(6′)-Ib-cr] (Robicsek et al., 2006). Since it was first identified, this latter enzyme has been detected in a large number of geographical regions in numerous genetic environments (Strahilevitz et al., 2009). It is usually found as a gene cassette in different integrons and associated to quinolone resistance genes such as qnrA1, qnrB2, qnrB4, qnrB6, qnrB10, qnrS1, qnrS2, and qepA or β-lactamase genes such as blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-24, blaDHA-1, blaSHV-12, and blaKPC-2 (Strahilevitz et al., 2009).

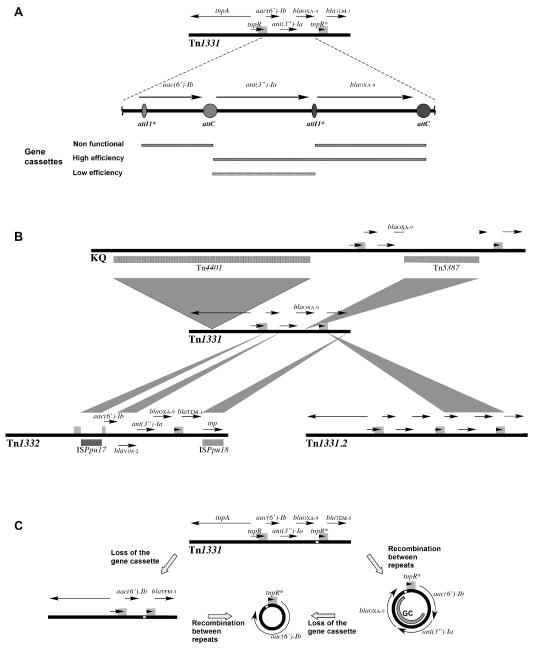

The prevalence of AAC(6′)-Ib together with its numerous variants attracted the interest of several research groups that studied them from different points of view. The aac(6′)-Ib gene is mostly found as a gene cassette within class 1 integrons or as a defective gene cassette within an unusual structure resembling the variable portion of the integrons but lacking the 5′ and 3′ conserved regions as in Tn1331 and its derivatives Tn1331.2, Tn1332 or the KQ element (Chamorro et al., 1990; Dery et al., 1997; Poirel et al., 2006; Rice et al., 2008; Sarno et al., 2002; Soler Bistue et al., 2008; Tolmasky et al., 1988; Tolmasky and Crosa, 1987). The structures of Tn1331 and the modifications occurred for the generation of Tn1331.2, Tn1332, and the KQ element are shown in Fig. 2. Interestingly, the aac(6′)-Ib environment found in these genetic elements has a number of particular characteristics. While in integrons the gene located at the 5′ end of the variable region is preceded by an attI recombination site located adjacent to the intI gene (Partridge et al., 2000), in these elements there is no attI upstream of the aac(6′)-Ib gene. Instead, an 8 bp sequence known as attI1* is found near the beginning of the structural gene at the location where a gene fusion between a blaTEM gene and a precursor of aac(6′)-Ib is believed to have occurred, incorporating the first six amino acids of the TEM β-lactamase at the N-terminus of this version of AAC(6′)-Ib (Fig. 2A) (Ramirez et al., 2008; Tolmasky, 1990). These features define an imperfect gene cassette with attI1* at the 5′ end within the aac(6′)-Ib structural gene (Fig. 2A). IntI1 integrase-mediated excision of this imperfect gene cassette could not be detected in cells harboring a recombinant clone with intI1 under the control of the Ptac promoter (Ramirez et al., 2008). Products of evolution of the Tn1331 transposon by insertion of DNA fragments or duplications have been found and are shown in Fig. 2B. This version of the aac(6′)-Ib gene was also found in the chromosome of a P. mirabilis isolate as part of a mosaic structure containing several resistance genes (Zong et al., 2009). In this case the upstream region of the gene is derived from Tn1331 but it shows a different organization, it is preceded by the region located downstream of blaOXA-9 in Tn1331. The authors of this report proposed that homologous recombination events between the duplicated regions of Tn1331 could have led to formation of a circular molecule that could have then been integrated into the chromosome (Fig. 2C) (Zong et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

A. Genetic map of the Tn1331 transposon with the region including genes aac(6′)-Ib, aadA1 and blaOXA-9 amplified. Circles and ovals represent attC and attI1* loci respectively. For clarity the points of potential crossover reactions are not indicated but they can be found in Ramirez et al. (Ramirez et al., 2008). Regions with a gene cassette structure are indicated below the genetic map by bars of different patterns. Their functionality as determined in recombination assays in the presence of IntI1 expressed from a recombinant clone harboring intI1 under the control of the Ptac promoter is shown. Directly repeated regions are shown as gray boxes on the sequences. B. Genetic maps of Tn1331, Tn1331.2, Tn1332, and the KQ element. Shadowed areas show the fragments inserted within the Tn1331 sequence that generated the other three genetic elements. C. Model for generation of a circular molecule containing aac(6′)-Ib (Zong et al., 2009). The white box indicates the DNA region that is found upstream of the gene in P. mirabilis JIE273. GC, gene cassette. Circular molecules are not drawn to scale.

The translation of the aac(6′)-Ib7 gene cassette has been studied in some detail. This is one of about 20% of gene cassettes that lack a discernible translation initiation region. Instead, a short open reading frame is located immediately upstream of the structural gene that significantly enhances translation through translational coupling (Hanau-Bercot et al., 2002; Jacquier et al., 2009).

A large number of variants of AAC(6′)-Ib have been found that differ at the N-terminal end, a phenomenon that may be a consequence of the high mobility of the gene. The fact that most of all of these variants are active shows a high flexibility in the structural requirements at this portion of the protein. This property has been proposed to be a contributing factor to the successful distribution and predominance among aminoglycoside resistant Enterobacteriaceae (Casin et al., 1998).

The AAC(6′)-Ib protein has been the subject of numerous mutagenesis as well as structural and mechanistic studies (Casin et al., 2003; Chavideh et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2007; Maurice et al., 2008; Panaite and Tolmasky, 1998; Pourreza et al., 2005; Rather et al., 1992; Shmara et al., 2001; Vetting et al., 2004; Vetting et al., 2008). Significant progress in understanding AAC(6′)-Ib and its variants has been achieved recently after the elucidation of the crystal structures of AAC(6′)-Ib and the extended spectrum AAC(6′)-Ib11 in conjunction with the construction of a molecular model of AAC(6′)-Ib-cr (Vetting et al., 2008). These studies showed that unlike AAC(6′)-Ii and AAC(6′)-Iy, which are dimers (Draker et al., 2003; Vetting et al., 2004; Wybenga-Groot et al., 1999), AAC(6′)-Ib and AAC(6′)-Ib-cr exist as a monomer while AAC(6′)-Ib11 shows monomer/dimer equilibrium (Maurice et al., 2008). Structural features behind the ability of AAC(6′)-Ib to catalyze acetylation of semisynthetic aminoglycosides, as well as the ordered kinetic mechanism could be explained (Maurice et al., 2008). Furthermore, a flexible flap was identified in AAC(6′)-Ib11 that might explain its ability to utilize as substrate both amikacin and gentamicin (Maurice et al., 2008). The modeling of AAC(6′)-Ib-cr, which has the substitutions D179Y and W102R with respect to AAC(6′)-Ib, permitted to determine that the Asp179Tyr substitution produces the greatest structural effect that results in an enhanced binding to the antibiotic molecule and the W102R acts by stabilizing the positioning of the Y179 (Robicsek et al., 2006; Strahilevitz et al., 2009). This attractive model explains the effects of each individual substitution. While D179Y is enough to confer a partial resistance phenotype, the effect of W102R is hardly detectable. Another model that emphasizes plasticity in the active site has also been suggested (Maurice et al., 2008). Quick methods for identification and genotyping of aac(6′)-Ib-cr have recently been published (Bell et al., 2010; Hidalgo-Grass and Strahilevitz, 2010).

Detailed subcellular localization studies of the AAC(6′)-Ib encoded by Tn1331 using physical separation methods together with gene fusions to phoA in which the signal peptide coding sequence has been removed, and fluorescence microscopy in which the gene was fused to the cyan fluorescent protein demonstrated that the enzyme is evenly distributed within the cytoplasmic compartment of E. coli (Dery et al., 2003). Care should be taken when determining the subcellular location of aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. In the past there were contradictory reports indicating that they are located in the periplasmic space or the cytosol (Franklin and Clarke, 2001; Perlin and Lerner, 1981; Tolmasky, 2007a; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003; Vliegenthart et al., 1991a). These contradictory findings could be due to the fact that in osmotically shocked E. coli, proteins are released through a molecular sieve formed by the damaged cell envelope (Vazquez-Laslop et al., 2001). As a consequence, cytoplasmic proteins small in native size tend to be released after osmotic shock treatment while larger proteins or protein complexes remain inside the cells (Vazquez-Laslop et al., 2001). We confirmed this by extracting the periplasmic proteins by spheroplast formation under different conditions and found that while the controls behaved as expected under all conditions, when we used mild conditions the AAC(6′)-Ib signal was present in the cytosolic extract but when we used harsher conditions a considerable fraction of the total AAC(6′)-Ib was found in the periplasmic extract (Dery et al., 2003; Tolmasky, 2007a).

Two shorter proteins of this class, AAC(6′)-29a and AAC(6′)-29b, have been identified from a multidrug-resistant clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa (Magnet et al., 2003; Poirel et al., 2001). The 131-amino acids AAC(‘6)-29b protein was studied in more detail and it was found that it does not mediate resistance by enzymatic modification but rather by tightly binding aminoglycoside molecules, a result that led to the conclusion that the mechanism of aminoglycoside resistance mediated by this protein is by sequestering the drug as a result of tight binding to the molecule (Magnet et al., 2003).

3.3. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes: aminoglycoside O-nucleotidyltransferases (ANTs)

ANTs mediate inactivation of aminoglycosides by catalyzing the transfer of an AMP group from the donor substrate ATP to and hydroxyl group in the aminoglycoside molecule. There are five classes of ANTs that catalyze adenylylation at the 6 [ANT(6)], 9 [ANT(9)], 4′ [ANT(4′)], 2″ [ANT(2″)], and 3″ [ANT(3″)] positions, of which only ANT(4′) includes two subclasses, I and II (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Aminoglycoside O-nucleotydyltransferases

| ANTs | gene names | Genetic location |

Accession number |

Host | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANT(6)-Ia | ant(6)-Ia, ant6, aadE | Plasmid, chromosome |

NC_006663, NC_012924, GQ900487 |

Staphylococcus

epidermidis, E. faecium, Streptococcus suis, S. aureus |

(Gill et al., 2005; Holden et al., 2009) |

| ant6 | Plasmid | AB247327 | E. faecalis | ||

| aadE | Chromosome | NC_013853 | Streptococcus mitis | ||

| aadK | Chromosome | M26879 | B. subtilis, Bacillus spp. | (Noguchi et al., 1993; Ohmiya et al., 1989) |

|

| aadE | Plasmid | AJ489618 | C. jejuni | ||

| aad(6) | Plasmid |

NC_008445, AY712687 |

E. faecalis, Streptococcus

oralis |

(Cerda et al., 2007; Schwarz et al., 2001) |

|

| ANT(6)-Ib | ant(6)-Ib | Transferable pathogenicity island |

FN594949, NZ_ABDU0 1000081 |

C. fetus subsp. fetus, B.

subtilis |

(Abril et al., 2010) |

| ANT(9)-Ia | ant(9)-Ia, aad(9), spc | Plasmid, transposon |

X02588, GU235985 |

S. aureus, Enterococcus spp., Sathylococcus sciuri |

(Murphy, 1985) |

| ANT(9)-Ib | ant(9)-Ib, aad(9), spc | Plasmid | M69221 | E. faecalis | (LeBlanc et al., 1991) |

| ANT(4′)-Ia C |

ant(4′)-Ia, aadD2, aadD,

ant(4′,4″)-I |

Plasmid |

U35229, M19465 |

S. epidermidis, S. aureus, Enterococcus spp., Bacillus spp. |

(McKenzie et al., 1986; Santanam and Kayser, 1978) |

| ANT(4′)-IIa | ant(4′)-IIa | Plasmid | M98270 |

P. aeruginosa,

Enterobacteriaceae |

(Jacoby et al., 1990) |

| ANT(4′)-IIb | ant(4′)-IIb | Transposon | AY114142 | P. aeruginosa | (Sabtcheva et al., 2003) |

| ANT(2″)-Ia | ant(2″)-Ia, aadB | Plasmid, integron |

X04555 |

P. aeruginosa, K.

pneumoniae , Morganella morganii, E. coli, S. typhimurium, C. freundii, A. baumannii |

(Cameron et al., 1986) |

| ANT(3″)-Ia |

ant(3″)-Ia, aadA, aadA1,

aad(3″)(9) |

Plasmid, transposon, integron |

X02340 |

Enterobacteriaceae, A.

baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Vibrio cholerae |

(Hollingshead and Vapnek, 1985; Tolmasky, 1990) |

| aadA2 | Plasmid, integron |

NC_010870 |

K. peneumoniae, Salmonella spp., Corynebacterium glutamicum, C. freundii, Aeromonas spp. |

(Chen et al., 2007) | |

| aadA3 | Plasmid, transposon, integron |

AF047479 | E. coli | (Parent and Roy, 1992) | |

| aadA4 | Plasmid, chromosome |

NC_002928, NC_010558 |

Bordetella parapertussis,

E. coli |

(Parkhill et al., 2003; Perichon et al., 2008) |

|

| aadA5 | Plasmid, transposon, integron |

AF137361 |

E. coli, K. pneumoniae,

Kluyvera georgiana, P. aeruginosa, E. cloacae |

(Sandvang, 1999) | |

| aadA6 | Integron | AM087411 | P. aeruginosa | (Fiett et al., 2006) | |

| aadA7 | Integron | AB114632 |

V. fluvialis, P. aeruginosa,

E. coli, V. cholerae, S. enterica |

(Ahmed et al., 2004) | |

| aadA8 | Plasmid, integron |

AY139603 |

V. cholerae, K.

pneumoniae, Bacillus endophyticus |

(Tennstedt et al., 2003) | |

| aadA9 | Plasmid | NC_003227 | C. glutamicum | (Tauch et al., 2002) | |

| aadA10 | Plasmid, integron |

AM087405 | P. aeruginosa, E. coli. | (Fiett et al., 2006; Partridge et al., 2002) |

|

| aadA11 | Integron |

AJ567827, AY758206 |

E. coli, P. aeruginosa. | (Llanes et al., 2006) | |

| aadA12 | Integron | FJ381668 |

E. coli, Yersinia

enterocolitica, S. enterica |

(Ajiboye et al., 2009) | |

| aadA13 | Plasmid, integron |

NC_010643 |

Pseudomonas rettgeri, P.

aeruginosa, Y. enterocolitica, E. coli |

(Revilla et al., 2008) | |

| aadA14 | Plasmid | AJ884726 | Pasteurella multocida | (Kehrenberg et al., 2005) | |

| aadA15 | Integron | DQ393783 | P. aeruginosa | (Yan et al., 2006) | |

| aadA16 | Plasmid, integron |

EU675686 |

E. coli, V. cholerae, K.

pneumoniae |

(Wei et al., 2009) | |

| aadA17 | Integron | FJ460181 | Aeromonas media | ||

| aadA21 | Integron | AY171244 | Salmonella spp. | (Faldynova et al., 2003) | |

| aadA22 | Plasmid, integron |

AM261837 | S. enterica, E. coli | (Herrero et al., 2008) | |

| aadA23 | Integron | AJ809407 | S. enterica | (Michael et al., 2005) | |

| aadA24 | Integron | DQ677333 | Salmonella spp. | (Egorova et al., 2007) | |

| aadA6/aadA10 | Integron | AM087405 | P. aeruginosa | (Fiett et al., 2006) |

Only representative hosts, references and accession numbers are shown.

C, three dimensional structure has been resolved. ANT(4′)-Ia pdb id: 1KNY (Pedersen et al., 1995).

3.3.1. ANT(6)

Genes coding for enzymes with related amino acid sequences have been named ant(6)-Ia, ant6, ant(6), and aadE. They all exhibit the same substrate profile (resistance to streptomycin) and therefore belong into the same subclass, but they are not identical. These genes are highly widespread among gram-positive bacteria (Tolmasky, 2007a; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). Two genes called aadE with 87% identity at the amino acid level were found in the E. faecalis plasmid pRE25 and in C. jejuni (Schwarz et al., 2001). Genes coding for ANT enzymes are found in plasmids, transposons, and chromosomes. The ant(6) gene is often found in a cluster ant(6)-sat4-aph(3′)-III that specifies resistance to aminoglycosides and streptothricin (Cerda et al., 2007). This cluster is part of Tn5405 and other related transposons, which are distributed among Staphylococci and Enterococci (Werner et al., 2003) and are located in plasmids and chromosomes. Another gene originally found in Bacillus subtilis was named aadK (Noguchi et al., 1993) and was subsequently found in other species of Bacillus (Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). The protein encoded by this gene shows 58% identity and 74% similarity with one encoded by an aadE gene (Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). A novel ant(6) gene, named ant(6)-Ib, was recently identified in Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus within a transferable pathogenicity island (Abril et al., 2010). This gene is identical to that called aad(6) in a contig of an unfinished Clostridium genome (accession number NZ_ABDU01000081).

3.3.2. ANT(9)

Two enzymes with the ANT(9) characteristics have been described, ANT(9)-Ia and ANT(9)-Ib, both mediating resistance to spectinomycin. The genes coding for these enzymes were called as ant(9)-Ia and ant(9)-Ib, but unfortunately they have both also been called spc or aad(9) facilitating confusion. The amino acid sequences of ANT(9)-Ia and ANT(9)-Ib share 39% identity. ANT(9)-Ia was first described in S. aureus and then also in Enterococcus avium, E. faecium, and E. faecalis. In all four bacteria the gene was part of Tn554 (Mahbub Alam et al., 2005; Murphy, 1985). Our BLAST analysis showed a protein with 100% identity to ANT(9)-Ia present as part of a novel transposon, Tn6072 (Chen et al., 2010). However, although the gene is correctly named as spc it is described as a streptomycin 3′-adenyltransferase. ANT(9)-Ib was found in a plasmid from E. faecalis (LeBlanc et al., 1991).

3.3.3. ANT(4′)

ANT(4′)-Ia is found in plasmids of gram-positives such as Staphylococci, Enterococci, and Bacillus spp., and the gene has been also named aadD, aadD2, and ant(4′,4″)-I (Bozdogan et al., 2003; Kobayashi et al., 2001; Muller et al., 1986; Perez-Vazquez et al., 2009). This latter name is due to the fact that this enzyme was found to modify 4′ and 4″ groups, which makes it capable of conferring resistance to dibekacin, an aminoglycoside that lacks a 4′ target (Santanam and Kayser, 1978). Both subclasses, I and II, confer resistance to tobramycin, amikacin, isepamicin, but subclass I also codifies resistance to dibekacin. ANT(4′)-Ia is the only ANT enzyme for which the three dimensional structure has been resolved (Pedersen et al., 1995). An ANT(4′) was also the subject of NMR studies to clarify aspects of the process of the recognition of the substrate (Revuelta et al. 2008). Two ANT(4′)-II enzymes have been described in gram-negative bacilli. These enzymes do not modify dibekacin, and therefore they must be unable to use the position 4″ as target. ANT(4′)-IIa was identified in plasmids of Pseudomonas and Enterobacteriaceae (Jacoby et al., 1990), and ANT(4′)-IIb was identified more recently in a P. aeruginosa transposon (Coyne et al., 2010).

3.3.4. ANT(2″)

This class consists only of ANT(2″)-Ia (Cameron et al., 1986), an enzyme that is widely distributed as a gene cassette in class 1 and 2 integrons (Ramirez et al., 2005; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003) and mediates resistance to gentamicin, tobramycin, dibekacin, sisomicin, and kanamycin. Therefore it is commonly encoded by plasmids and transposons. This enzyme, encoded by a gene more commonly called aadB, is present in enterobacteria and non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli.

3.3.5. ANT(3″)

These are the most commonly found ANT enzymes, they specify resistance to spectinomycin and streptomycin, and the coding genes are most commonly named aadA (Hollingshead and Vapnek, 1985). At least 22 highly related gene versions are found in GenBank, that are identified as aadA1 through aadA24, but some numbers are missing. The alternative nomenclature for the protein coded for by aadA1 is ANT(3″)-Ia. Another name used to identify ANT(3″)-Ia is AAD(3″)(9). The aadA genes exist as gene cassettes and are part of a large number of integrons, plasmids and transposons. They can be part of unusual gene cassettes and exist as gene fusions as described in the following paragraphs.

In Tn1331, the aadA1 [ant(3″)-Ia] gene is present within two unusual gene cassette structures (see Fig. 2A). At the 3′ end of the gene, instead of the usual attC site, there is a copy of attI1*, which may have been formed by an illegitimate recombination event between the attC site located 3′ of aadA1 of an integron and the attI1 locus located 5′ of blaOXA-9 of another integron in which the blaOXA-9 gene cassette is adjacent to the 5′-conserved sequence (Sarno et al., 2002). The resulting structure defines a gene cassette consisting of aadA1-attI1* but that lacks the usual attC site, and another gene cassette that includes two genes aadA1-attI1*-blaOXA-9–attC (see Fig. 2A) (Ramirez et al., 2008; Sarno et al., 2002; Tolmasky, 1990; Tolmasky and Crosa, 1993). While the aadA1-attI1* gene cassette is excised by the IntI1 integrase at a very low frequency the gene cassette that includes both genes is fully functional (Ramirez et al., 2008).

The aadA genes are also found fused to other resistance enzymes, e.g., in a P. aeruginosa class 1 integron aadA15 is fused 3′ of blaOXA-10 (Yan et al., 2006) and aadA6 is fused to aadA10 in another P. aeruginosa class 1 integron (Fiett et al., 2006). The aadA1 and aadA4 genes were also found disrupted by insertion of IS26 (Adrian et al., 2000; Han et al., 2008).

The ant(3″)-Ia gene is part of numerous transposons, some of them exhaustively studied such as: a) Tn21 and other related transposons of what is known as the Tn21 subfamily. These transposons are widely disseminated probably as a result of the association of an integron and a gene conferring resistance to a toxic metal within the same mobile element (Liebert et al., 1999); b) Tn1331, already described above; and c) Tn7, which includes in its structure a class 2 integron (Hansson et al., 2002).

3.4 Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes: aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferases (APHs)

APHs catalyze the transfer of a phosphate group to the aminoglycoside molecule (Wright and Thompson, 1999). The classes and subclasses are: APH(4)-I, APH(6)-I, APH(9)-I, APH(3′)-I through VII, APH(2″)-I through IV, APH(3″)-I, APH(7″)-I (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

3.4.1. APH(4)

There are two enzymes within the only subclass defined in this group: APH(4)-Ia (Kaster et al., 1983) and APH(4)-Ib (Zalacain et al., 1986), whose genes have also been named hph and hyg, respectively. These enzymes mediate resistance to hygromycin and are not clinically relevant. These genes have been used in the construction of cloning vehicles for both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Abhyankar et al., 2009; Gritz and Davies, 1983).

3.4.2. APH(6)

There are 4 enzymes in the only described subclass of APH(6)s, which confer resistance to streptomycin. The aph(6)-Ia, also known as aphD and strA, was originally found in the chromosome of Streptomyces griseus (Distler et al., 1987). The aph(6)-Ib was also named sph and was found in Streptomyces glaucescens (Vogtli and Hutter, 1987). The gene coding for APH(6)-Ic is one of three resistance genes present in Tn5, a composite transposon found in gram-negatives (Steiniger-White et al., 2004). Although this transposon is not widely distributed, it has been extensively studied and modified as tool for molecular genetics (Steiniger-White et al., 2004). The aph(6)-Id gene, also denominated strB and orfI, was first found in the plasmid RSF1010, a 8,684 bp broad host range multicopy plasmid RSF1010 that can replicate in most gram-negative bacteria and also in gram-positive actinomyces, and is also known as R300B and R1162 (Meyer, 2009). This plasmid was also the first source identified for another APH, aph(3″)-Ib (see below), which is contiguous to aph(6)-Id. These genes are part of a fragment that includes the genes repA, repC, sul2, aph(3″)-Ib, and aph(6)-Id that has been found, complete or in part, within plasmids, integrative conjugative elements, and chromosomal genomic islands (Daly et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2008). As a consequence of the dissemination of this DNA fragment, the aph(6)-Id and aph(3″)-Ib genes are found in both gram-positives and gram-negatives.

3.4.3. APH(9)

The aph(9)-Ia gene was first found in Legionella pneumophila (Suter et al., 1997). BLAST analysis of this nucleotide sequence also showed that there is a gene with 87% homology within the genome of L. pneumophila strain Lens that is identified as aph (Cazalet et al., 2004). The APH(9)-Ia has been the subject of detailed analysis. The enzyme was overproduced and purified, and it was determined that it does not bind to any tested aminoglycoside other than spectinomycin (Thompson et al., 1998). The Km and kcat values were also determined and the reaction product was purified and characterized by mass spectrometry and 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR (Thompson et al., 1998). Further studies led to determination of the crystal structures of APH(9)-Ia in its apo form, its binary complex with the nucleotide, AMP, and its ternary complex bound with ADP and spectinomycin (Fong et al., 2010). These structures showed that APH(9)-Ia presents similar folding to APH(3′) and APH(2″) enzymes but differs significantly in its substrate binding area and in undergoing a conformation change upon ligand binding (Fong et al., 2010).

The phosphotransferase APH(9)-Ib isolated from Streptomyces flavopersicus (Str. netropsis) has also been called SpcN and it has no significant homology to that of L. pneumophila. A BLAST analysis of this aph(9)-Ib gene nucleotide sequence showed 78-79% identity with genes from 3 Stretomyces spectabilis strains (Lyutzkanova et al., 1997). Despite of the differences these genes are also called spcN in GenBank.

3.4.4. APH(3′)

The APH(3′)-I subclass shows a resistance profile including kanamycin, neomycin, paromomycin, ribostamycin, lividomycin, is composed of three enzymes that are widely distributed mainly among gram-negatives within wide host range plasmids and transposons (Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). The aph(3′)-Ia gene, also known as aphA-1, is part of the well known Tn903 transposon (Bernardi and Bernardi, 1991) and it is commonly used as marker gene in cloning vehicles. The aph(3′)-Ib gene is part of the wide host range conjugative RP4 plasmid (Pansegrau et al., 1987). This gene was originally named aphA. The aph(3′)-Ic gene, also called aphA7 and aphA1-Iab, is part of plasmids and transposons and its wide distribution includes Corynebacterium spp. (Tauch et al., 2000; Vakulenko and Mobashery, 2003). This gene has also been included in cloning vehicles.

The APH(3′)-II subclass includes three isozymes that specify resistance to kanamycin, neomycin, butirosin, paromomycin, and ribostamycin. The APH(3′)-IIa, also known as aphA-2 is one of the three resistance genes encoded by Tn5 (Steiniger-White et al., 2004) (see above) and it is used as resistance marker in cloning vectors for both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Wright and Thompson, 1999). The enzyme coded by this gene has been characterized in detail and its crystal structure in complex with kanamycin has been resolved (Nurizzo et al., 2003; Siregar et al., 1994). The aph(3′)-IIb gene was identified in the P. aeruginosa chromosome (Winsor et al., 2005) and the third member of this subclass, aph(3′)-IIc, was recently defined in S. maltophilia but an accession number is not available (Okazaki and Avison, 2007).