Abstract

China’s methadone maintenance treatment program was initiated in 2004 as a small pilot project in just eight sites. It has since expanded into a nationwide program encompassing more than 680 clinics covering 27 provinces and serving some 242 000 heroin users by the end of 2009. The agencies that were tasked with the program’s expansion have been confronted with many challenges, including high drop-out rates, poor cooperation between local governing authorities and poor service quality at the counter. In spite of these difficulties, ongoing evaluation has suggested reductions in heroin use, risky injection practices and, importantly, criminal behaviours among clients, which has thus provided the impetus for further expansion. Clinic services have been extended to offer clients a range of ancillary services, including HIV, syphilis and hepatitis C testing, information, education and communication, psychosocial support services and referrals for treatment of HIV, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases. Cooperation between health and public security officials has improved through regular meetings and dialogue. However, institutional capacity building is still needed to deliver sustainable and standardized services that will ultimately improve retention rates. This article documents the steps China made in overcoming the many barriers to success of its methadone program. These lessons might be useful for other countries in the region that are scaling-up their methadone programs.

Keywords: Methadone maintenance treatment, scaling-up, national program, challenges, China

Introduction

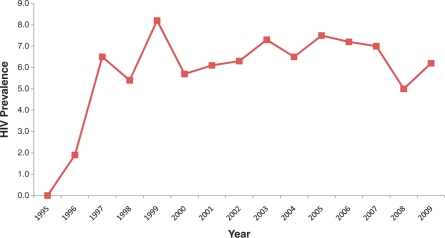

Under the leadership of Chairman Mao, China experienced a relatively drug-free period between the 1950s and the 1970s.1–5 However, in the late 1970s, the country underwent economic reforms and the illicit drug trade re-emerged, first within the border areas adjacent to the ‘Golden triangle’, then along drug trafficking routes to other parts of the country.2,6,7 In 1989, the first HIV outbreak was identified among 146 injecting drug users in Yunnan province.8 Since then, China has observed an ever-growing HIV/AIDS epidemic, initially fuelled by injecting drug users.9 In 2001, up to 66.5% of newly diagnosed HIV infections were related to drug use.10 Harm reduction efforts began in 2003 and have slowed the pace of HIV infection among drug users;11 HIV prevalence has stabilized and reduced, particularly since 2005 (Figure 1), with the overall growth rate of newly reported cases having decreased from 9.0% in 2006 to 5.8% in 2009.12 However, drug users still represent a major driver of the HIV epidemic in China.

Figure 1.

HIV sentinel surveillance data for drug users, 1995–2009

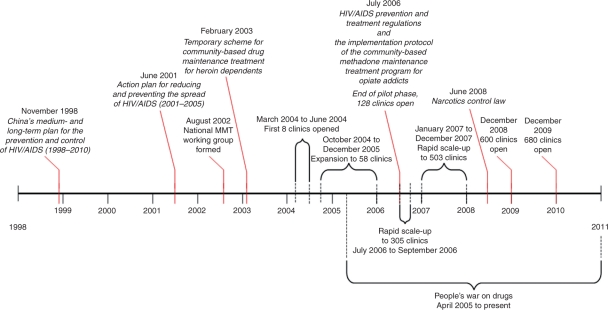

In the early 1990s, government officials began the lengthy process of understanding how best to constrain the dual epidemic of HIV and drug use.13 This included learning from other countries, developing policies and plans suitable to China, piloting harm reduction strategies and ultimately implementing a multifaceted program to slow the HIV epidemic among drug users. A major component of this program has been the methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) program, which was initiated in 2004. The program was rapidly expanded from the initial pilot of just 8 clinics serving 1029 drug users in 2004 to 680 clinics serving 112 831 drug users daily in 2009. This article provides a detailed roadmap of this process, and discusses emerging issues and responses that contributed to the development of the world’s largest MMT program14 and the challenges still faced in the expansion of its services (summarized in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Timeline of events in the development of China’s MMT program

The Pilot Phase

Development of a supportive policy environment

When first introduced, harm reduction was controversial because it conflicted with laws and regulations on narcotics control. Thus, despite a large body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of MMT,15–17 it was initially difficult to convince government officials, especially those in law enforcement, to try this strategy. In order to do so, public health professionals from the National Center of AIDS/STD Control and Prevention (NCAIDS) took the bold step to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of MMT by conducting pilot interventions, predicting the trend of the epidemic and advocating for evidence-based policy.

As early as the mid-1990s, Chinese officials began to organize study tours to learn from the experiences of other nations, such as Australia, the USA, the UK and The Netherlands.13 Delegations typically consisted of officials from the Ministries of Health, Public Security, Justice, Education and Finance. These tours influenced the attitudes of key officials towards harm reduction, making them more amenable to the idea of tailoring such strategies to the Chinese context. Further reinforcement came in the form of frequent workshops, conferences and seminars among key sectors as well as with international agencies, such as the WHO, United Nations (UN) and World Bank, and academic institutions, both local and international. These meetings opened dialogue on the issues and built a foundation for future collaboration between sectors, which ultimately led to a consensus to trial MMT in China.

In the meantime, the underlying policy environment was changing. Prior to 2001, efforts focused on policy advocacy and development. The Medium- and Long-Term Strategic Plan for HIV/AIDS (1998–2010)18 issued in 1998 was China’s first HIV-specific policy document with clear targets. It resolved to contain the rapid spread of HIV among injecting drug users by 2002 and mandated HIV/STD education in drug rehabilitation centres and prisons, as well as in schools. This plan was superseded by the National Action Plan on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Containment (2001–2005) issued in 2001,19 in which it was recognized that the HIV epidemic among injecting drug users had still not been brought under control. Thus, higher targets for educational interventions were set and harm reduction as a control strategy was formally introduced. The Plan called for a pilot of pharmacotherapy to treat drug users in therapeutic institutions, with the guidelines to be developed and approved by the Ministries of Health and Public Security.

The National Working Group and pilot protocol

A National Working Group for Community-based Maintenance Treatment for Opiate Users (hereafter referred to as the National Working Group) was established in August 2002, consisting of members of the Ministries of Health, Public Security, and the State Food and Drug Administration, and three experts on addiction and HIV/AIDS. The National Working Group was given overall responsibility for managing the program, supervising the operation and overseeing its expansion. At the provincial and county level, working groups have also been established to take on these duties locally. The NCAIDS serves as the secretariat for the National Working Group, which is tasked with executing the national plan, coordinating the implementation, providing technical support to the clinics and conducting routine monitoring and evaluation. The National Working Group members meet regularly to identify potential gaps, resolve emerging issues and refine the management of the program. The first task was to develop guidelines for the MMT pilot. Prior to development of the guidelines, the Secretariat arranged visits to MMT clinics in Hong Kong, the USA, the UK and The Netherlands in order to develop a plan based on international best practices. The national guidelines were drafted by the Secretariat, reviewed by National Working Group members, and further consultation was sought from stakeholders. In February 2003, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Public Security and the State Food and Drug Administration jointly issued the Temporary Scheme for Community-based Drug Maintenance Treatment for Heroin Dependents. This protocol laid the foundation for administrative and technical support at all levels of government, from national to local. The Temporary Scheme prioritized MMT implementation in those areas most severely affected (more than 500 drug users) and outlined eligibility criteria for participation. The eligibility criteria to participate in MMT were: (i) opiate users who had failed more than one attempt to quit; (ii) at least two terms in a detoxification centre or once in a re-education-through-labour detoxification facility; (iii) at least 20 years of age; (iv) a local resident and settled in the local area where the clinic was located; and (v) capable of complete civil liability. Drug users testing HIV-positive needed only to fulfil requirements (iv) and (v) to qualify. Clients were permitted to miss a maximum of 15 days in 90 days, or risked expulsion. They could also be expelled for not cooperating with clinic doctors or failing to obey program regulations, which included maintaining abstinence from opiate use while in treatment.

The temporary scheme also outlined the safety and security protocol to guide methadone production, transport and distribution under the supervision of the State Food and Drug Administration. Methadone powder was purchased centrally and distributed to participating provinces, which have each assigned one pharmaceutical body to produce methadone liquid according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. In addition, it was stipulated that the maximum daily cost for a drug user receiving MMT services is 10 Chinese Yuan per day (∼US$1.20), irrespective of dosage. Patients had to appear in person to collect their daily dose.

The first eight MMT pilot clinics

Between March and June 2004, the first eight MMT clinics were established: two in Sichuan, one in Yunnan, two in Guizhou, one in Guangxi and two in Zhejiang. The locations of the clinics were based on need and the local government agencies’ willingness to participate. A total of 1029 clients were enrolled during the first calendar year of the pilot. To estimate the effectiveness of these first eight clinics, the national secretariat established a monitoring and evaluation system. (This system has since become the basis for an internet-based database that all clinics use to enter and update information on their clients and services.) At entry, 6 and 12 months, 585, 609 and 468 clients, respectively, were surveyed to assess changes in drug using behaviours, drug-related criminal activity, employment, family relationship and HIV status.20 After 6 months, the proportion of clients who injected drugs had reduced from 69.1 to 8.9 to 8.8%, and the frequency of injection in the past month had reduced from 90 times per month to 2 times per month. The proportion of clients reporting employment (permanent or temporary) increased from 22.9 to 40.6–43.2%, and self-reported engagement in criminal activity reduced from 20.7 to 3.6–3.8%. By the third survey, 65.8% of clients rated their relationship with their family as good, an increase from 46.8% at entry, and 95.9% of clients were satisfied with MMT services. Only eight HIV sero-conversions were found among 1153 sero-negative clients during the 12-month follow-up.20 It should be noted that these surveys were inherently biased because they were unable to measure outcomes among the 52% of clients who dropped out. Despite these limitations, as early as 6 months into the pilot, noticeable improvements among clients provided sufficient impetus to scale-up the program.

A major challenge during the pilot was retention. The National Working Group tried to address this problem by inviting various international experts to visit the clinics and conduct an external review. They observed that lower dosages of methadone and the absence of adequate counselling and psychosocial support for the clients were likely contributing to the high drop-out rate. The Secretariat encouraged further research on how to best improve the MMT program.

Review and expansion of the pilot

In 2004, the first national meeting on piloting MMT was convened among government officials from the three key ministries, including the vice-Minister for Health, Dr Longde Wang, and Yuanzhen Li, Deputy Director-General of the National Narcotics Bureau, as well as experts from related areas. The meeting served to share the experiences, and more importantly the problems, identified from the first phase, and to promote rapid scale-up throughout the country under the increasingly supportive environment. In addition, Premier Wen Jiabao discussed the scale-up of MMT in regions with a serious HIV/AIDS epidemic in his speech presented before the 15th International AIDS Conference in Bangkok in 2004, and Vice-Premier Wu Yi did the same in her speech at the 2004 State Council Special Assembly on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control.

Human resources were (and still are) one of the major impediments to the expansion of the MMT program. A national training centre was established in the Yunnan Institute of Drug Abuse to provide clinical and administrative training for key staff working in MMT clinics. Two specific training programs are provided to trainees. The first is a 10-day intensive training course covering addiction theory, clinical practice and administrative skills for delivery of MMT services. To date, some 2500 staff have received this training at the National MMT Training Centre. The second is hands-on training provided on-site by clinical addiction experts who assist local staff for the first 7 days after a clinic has opened, to guide them in the practice of addiction treatment and data management. Roughly, 2500 staff have received this training.

With growing political and technical support, the MMT program began to steadily expand. By the end of 2005, there were 58 MMT clinics opened in 11 provinces serving 8116 drug users. Another evaluation was conducted at 2 years to re-examine the program’s achievements and supported earlier findings of positive improvements among clients. Thus, the pilot period ended and the MMT program moved to national scale.

Legislative Support for a Rapid Expansion

In 2006, several important policy changes occurred. The first was promulgation of the HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment Regulations, which specifically endorsed the use of MMT as treatment for opiate addicts (Articles 27, 63).21 The adjoining Five-Year Action Plan to Control HIV/AIDS (2006–10) set specific targets for scaling up MMT; by the end of 2007 and 2010, MMT would be made available for no fewer than 40 and 70% of opiate users, respectively, in counties/districts with more than 500 registered drug users, and all drug users should have at least 90% basic HIV knowledge and condom use (Objective 6).22 Furthermore, the Ministry of Public Security issued an official notice to promote community-based MMT programs, while the State Food and Drug Administration issued regulation for the control of stupefacient and mental medicine use, which is relevant to methadone management.

Also, in July 2006, the National Working Group revised the Temporary Scheme to improve MMT services, and introduced The Implementation Protocol for Community-Based Methadone Maintenance Treatment for Opiate Addicts. Several crucial improvements were made to benefit and cover more target groups. Notably, the enrolment and exclusion criteria were relaxed. For example: (i) clients are no longer required to have a history of detoxification or several failed attempts to quit using drugs to enter the program; (ii) clients are no longer required to be registered as local residents and a transfer system has been set up to meet the needs of those who are relocating either permanently or temporarily; (iii) the number of allowable missing treatment days has been reduced to 7 consecutive days (a rare event); and (iv) relapse is no longer a strong reason for expulsion, though it could be considered grounds for expulsion since the informed consent still requires clients to promise not to use illegal drugs while in treatment. Furthermore, a detailed clinical guideline for methadone treatment was added to the protocol to support clinical practice and comprehensive interventions are highlighted in the new protocol that suggests clinics offer ancillary services. These include counselling, psychosocial support, testing for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis C and tuberculosis, referrals for antiretroviral treatment, peer education, health education, group activities, social support and skills training for employment. The treatment fee for MMT services was not specified, as in some areas where heroin is easily obtained at low cost, the fee is reduced or even waived.

With support from the above-mentioned legislation, a decision was made by senior government officials to accelerate the expansion. A target was set to open 300 clinics by the end of 2006. Recognizing the cost-effectiveness of MMT relative to compulsory detoxification, the Public Security Ministry challenged the Secretariat to meet this target by the end of September 2006. Under significant pressure, the team had 305 clinics operational by this time, with a total of 320 clinics opened by the end of that year, serving 37 345 drug users. The Ministry for Public Security’s rationale was this: if the average heroin user uses 0.6 g/day and the average price of heroin is CNY¥ 370 RMB/g (USD$47.44, at exchange rate of USD$1 = CNY¥7.8 RMB in 2006), they calculated that by bringing forward the opening date of about 200 more MMT clinics (101 clinics were already in operation by the end of July 2006) by 3 months, they could prevent the sale of 54 g ( = 0.6 g × 90 days) of heroin per person at a value of CNY¥ 19 980 RMB (USD$2561.54, at exchange rate of USD$1 = CNY¥7.8 RMB in 2006). Multiplied by the number of users, the initiative would avoid millions of dollars trade in heroin, not to mention the millions more saved in the community by reducing drug-related crimes. See supplementary data in IJE online for details.

The expansion did not stop there. In 2007, central government funding was also allocated to the program, enabling those places with less than 500 registered drug users to establish MMT clinics. Another target of 500 MMT clinics was set and 503 MMT clinics were cumulatively accomplished by the end of 2007, in 23 provinces serving 97 554 clients. By the end of 2009, there were 680 clinics with some 242 000 clients ever-enrolled, roughly half of whom remain in treatment. Areas of greatest need now have MMT clinics and the expansion has thus slowed down.

MMT clinics have now been opened in 27 provinces. They may be affiliated with a local Centre for Disease Control, hospital, psychosocial health centre, community-based health centre, voluntary detoxification centre or a hospital in the Public Security system. Flexibility has been enhanced by the introduction of mobile services; the first was in Yunnan and later in another nine provinces, with a total of 26 MMT vans. This service enables drug users in remote, rural areas to access to methadone. Flexibility has also been enhanced by longer and later operating hours at some clinics.

In June 2008, a revised Law on Drug Control was formally issued by the People’s Congress. The law has integrated MMT into the existing anti-drug strategies requiring drug users to undergo community-based, rather than forced, interned detoxification (up to 2 years), and to be provided with vocational training and employment assistance. Moreover, it requires ‘the health sectors of provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities to cooperate with Public Security and the Food and Drug Administration to implement community-based methadone maintenance treatment’. This law is an important sanction for the MMT program and will ensure its sustainability.

Monitoring and Evaluation

The role of the National Working Group

Regular monitoring and evaluation missions have been led by senior officials from the three relevant government sectors to improve multi-sector corporation at local levels and investigate reasons for high drop-out in certain clinics. During these missions, officials convene on-site multi-sectoral meetings at different levels, exchange opinions with local authorities, and hear the concerns of clinical staff, addiction experts and, most importantly, MMT clients. In 2008–9, there were three joint monitoring and evaluation missions, one each to Yunnan, Guangdong and Hainan, which were used to make recommendations for improving the program.

Every 2 years, a review meeting is organized by the National Working Group, which includes participants from the three relevant government sectors at national, provincial and county levels as well as representatives from the clinics. During these meetings, participants exchange and summarize their experiences and a field trip is organized to visit clinics that are performing well so that staff from other clinics can observe and learn how to improve their services.

The comprehensive web-based management database

A national MMT program database was developed in 2004 to monitor the pilot and was later upgraded to a web-based management database in 2008. This change was made as part of a general move towards improving the monitoring and evaluation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China. The database enables regular reporting on the implementation of the program. Such information can be used to identify gaps in the delivery of services in a timely manner.

Each of the clinics uploads its daily services records to the database in real time. This includes clients’ demographic information at the start of treatment, as well as their daily dose record and the results of any tests performed for opiate use, HIV, hepatitis C, syphilis and tuberculosis. Behavioural risk information is collected at entry, 6 months, 12 months and then at 12-month intervals thereafter. These data are also uploaded to the database, allowing the Secretariat to measure the relative change in clients staying in the program in order to evaluate the effectives of MMT for reducing HIV risks. However, some clinic staff fail to collect and upload patient information, which hinders evaluation efforts. The Secretariat is attempting to raise awareness among clinics as to the importance of data collection for monitoring and evaluation.

Challenges and Response

The MMT program in China is believed to have made a considerable impact on drug use and HIV infection among drug users in the country. In 2008 and 2009, respectively, an estimated 2969 and 3919 new HIV infections (excluding secondary transmission) were prevented, consumption of heroin was reduced by 17.0 tons and 22.4 tons, and $US939 million and US$1.24 billion in heroin trade were avoided. These achievements can be attributed to at least three factors: strong political commitment—the MMT program is supported legislatively and financially by the central government multi-sector cooperation; the incorporation of MMT clinics into existing medical infrastructure, which has facilitated delivery of services; and the leadership role of the National Working Group and hard work of local implementers. However, despite the progress made, there remain a wide range of challenges and gaps that need to be addressed to achieve the overall goal of universal access.

The coverage of MMT and improving retention

A major concern is that the current coverage of MMT may still be too low to have sufficient impact on the epidemic. To reverse or stabilize the HIV epidemic among drug users, it has been estimated that at least 60% of drug users need to be reached with effective interventions.23,24 In 2009, there were 1.27 million registered drug users in China, among whom some 600 000 were injecting drug users,25 although the total number of drug users (including those not registered) is presumed to be much higher. Conversely, only 240 000 opiate users have ever engaged in MMT, and in December 2009 <50% of those ever enrolled were still receiving treatment.

A problem closely related to coverage is retention, which is less than optimal. The major reason for the high dropout is thought to be dose.26 The average dose in 2009 was reported as 54 mg—below international recommendations of 60–100 mg/day.27 Low doses also contribute to relapse, which in turn contributes to low retention rates.26 It is possible that clinics prefer to administer lower doses in order to save money since clients pay CN¥10 (USD $1.28) per dose, regardless of the volume. Alternatively, given that most staff believe that the ultimate goal of MMT is complete detoxification, lower doses may seem preferable. Clinic practitioners have been encouraged to increase the methadone doses but many fail to do so. Clients are also reluctant to take higher doses as they expect that the goal of MMT should be abstinence, rather than maintenance. This suggests that the goals of MMT are not clearly explained to clients when they commence treatment. Staff have also expressed their desire for further training on how to manage patient regimens.28 The Implementation Protocol does not recommend any minimum length of stay or minimal daily dose for patients, but perhaps should give clearer guidance to staff on how to manage dosing regimens.

Another major factor contributing to poor retention and coverage is accessibility. In some areas, it is simply not cost-effective to provide methadone. Mobile clinics have helped to address this issue somewhat, but for higher coverage the program will also need to consider more flexible dosing strategies, such as take-home doses. Accessibility is also hindered by cost. Although the daily service fee is limited to CNY¥10 RMB (USD$ 1.28), clients may incur additional costs, such as transport (many clinics are not centrally located, even in the cities), which make the service too expensive for the very poor or those who live far away (some clients live >2 h travelling time from clinics). For some clients, the fee may be waived or reduced to help them adhere to treatment. A system to provide travel subsidies or other reimbursements to poor clients should be considered.

A further problem contributing to drop out is interruption of treatment due to incarceration or mobility. The program has attempted to address the mobility problem by allowing transfers between clinics. Interruptions to treatment due to incarceration are more difficult to resolve as they require coordination with law enforcements agencies in local. Many clients may find themselves being arrested and incarcerated due to relapse and will then be unable to continue treatment. This puts drug users at severe risk of infection with HIV, hepatitis C or other infections.29,30 Discussions with law enforcement authorities on how to implement MMT within such settings needs to be addressed by creative measures.

The quality of services provided

MMT clinics can and should be employed as a comprehensive service platform for the control of both HIV and drug use. Evidence exists from both China31,32 and abroad33 that relapse decreases when additional services are offered by the clinics. Ancillary services recommended by the Secretariat include counselling, psychosocial support, education, referrals for related health issues and incentives. Incentives such as reduced or waived fees are being introduced by some clinics for clients who successfully abstain from using other opiates while in MMT, attend group activities or refer other drug users to the program. These clinics have observed positive changes in client retention. Some other clinics, however, still focus solely on administering methadone and lack capacity to deliver ancillary services, leaving the service target unmet.

MMT clinics should also increase the range of services available and improve coordination with related services. Many drug users are at high risk of infection by HIV, hepatitis C, sexually transmitted infections and other blood-borne diseases.6 The average infection rates of HIV and hepatitis C are 8.5 and 65%, respectively, among the current MMT clients. Clients also present with tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections and other infections. Currently, clients needing treatment can only be referred for such services at most of the clinics. In addition, many clients continue to use drugs while in MMT and need access to needles, but these are also unavailable at MMT clinics. MMT clinics should offer a one-stop-shop for comprehensive services, e.g., referral services, counselling, social supports, needed by drug users, rather than merely provide methadone. This would save clients time and could improve adherence, retention and satisfaction with the service. It would benefit staff who would like to increase their range of skills (see next section). The different services should also work together to improve referrals between services to increase the numbers of clients in MMT. For example, designated tuberculosis clinics should refer drug users to MMT.

Staff capacity

Although staff do receive training, their knowledge and skills in addiction treatment and clinic management may be inadequate.30 Misunderstanding about the goals of MMT (i.e. maintenance, not abstinence) as well as confusion regarding treatment for clients on multiple treatments, such as HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis C co-infection, may have adverse consequences on prescribed dosage regimens and, ultimately, retention. Negative attitudes of staff towards patients can also affect retention. MMT clinic staff do not enjoy status and may receive a lower salary than their counterparts in other specialties.28 There is also little room for professional growth and many fear their skill set becomes too narrow in MMT.28 The professional and monetary needs of staff need to be addressed since staff stability has a positive impact on MMT programs.34 Staff management skills and their understanding of the need to collect data for evaluation also need to be improved. A series of new training curricula has recently been initiated, including courses on ‘Psychological counseling and support among injecting drug users’, but curricula to address other staff weaknesses, management and data collection should be introduced. Quality assurance monitoring by the MMT Secretariat is needed to ensure the training provided is of high quality and is adhered to, and to ensure that staff maintain professional, non-discriminatory attitudes towards clients.

Multi-sector cooperation at local level

Cooperation between the Ministries of Health and Public Security functions well at the central and provincial levels, but less so at lower levels. Public security and public health staff have different understandings of the nature of addiction, the importance of MMT and particularly the meaning of relapse as defined by a urine test. The fear of being registered as a drug user deters potential clients from exposing themselves and accessing the service; registered drug users are sometimes harassed by police.29 Clients may also fear arrest if police target clinics during crackdowns as part of the War on Drugs. The newly issued Narcotics Control Law has integrated MMT as a key indicator of drug control, which will hopefully convey the message that MMT is a dual approach both for drug control and HIV prevention. Training for public security officers to help them understand the principles and operation of MMT is being conducted but needs to reach more officers to improve their support for the program. It is hoped that increasing law enforcement officials’ levels of understanding about drug use will make them more amenable to the inclusion of MMT in closed settings.

Conclusion

China has made impressive progress in moving its MMT program from a pilot project to a national scale. Experiences and lessons learned from this period will be applied to continued improvement of the program. Many important challenges remain before the program will achieve its desired success. Key goals to improve the program include: (i) increasing the coverage of MMT and the number of its beneficiaries; (ii) improving accessibility of services; (iii) improving the quality of services offered, increasing the range of services offered at clinics and introducing referral systems between related services; (iv) providing on-going staff training to improve the quality of their service, increase their understanding of drug addiction and enhance their professionalism; and (v) enhancing multi-sector cooperation, especially at local levels to ensure that clients enjoy uninterrupted treatment. These improvements will enable the program to reach the ambitious targets set by the Government and improve the life of the drug users to reverse both the HIV/AIDS and drug abuse epidemics.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online for calculating benefits from bringing forward the opening date of about 200 more MMT clinics in 2006.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chinese National Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program. Preparation of the manuscript was partly supported by Multidisciplinary HIV and TB Implementation Sciences Training in China funded by US National Institute of Health, the Fogarty International Center and National Institute on Drug Abuse (China ICOHRTA2, NIH Research Grant #U2R TW06918, Principal Investigator Z.W.). S.G.S. was partially supported by a UC Pacific Rim Research Program Minigrant.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and clients of the methadone clinics around China for helping make the program a success.

Conflict of interest: Drs Y.H., X.S., F.L., J.L., Z.W. and Ms X.G. are members of China’s National MMT Working Group. They direct the overall development of national MMT program. Drs W.Y., K.R., C.W., X.C. and W.L. are members of the secretariat of national MMT program. They are responsible for daily operation of management of national MMT program.

KEY MESSAGES.

China has rapidly expanded methadone maintenance programs in response to HIV/AIDS epidemic among drug use population in past years;

Methadone treatment services have been extended to offer clients a range of ancillary services, including HIV, syphilis and hepatitis C testing, information, education and communication, psychosocial support services and referrals for treatment of HIV, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases;

Institutional capacity building at methadone clinics is still needed to deliver sustainable and standardized services that will ultimately improve methadone treatment program.

References

- 1.McCoy A. The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia, Central America, Columbia. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCoy CB, Lai S, Metsch LR, et al. No pain no gain, establishing the Kunming, China, drug rehabilitation center. J Drug Issues. 1997;27:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai YT. The anti-opium campaign movement in the early 1950s [Article in Chinese] CPC Hist. 2001;10:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNODC. 2008 World Drug Report. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang YL, Zhao D, Zhao C, Cubells JF. Opiate addiction in China: current situation and treatments. Addiction. 2006;101:657–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan SG, Wu Z. Rapid scale up of harm reduction in China. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W. Illegal drug abuse and the community camp strategy in China. J Drug Educ. 1999;29:97–114. doi: 10.2190/J28R-FH8R-68A9-L288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma Y, Li Z, Zhang K, et al. Identification of HIV infection among drug users in China [Article in Chinese] Chinese J Epidemiol. 1990;11:184–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.State Council AIDS Working Committee Office, UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China. A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China (2004) Beijing: China Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China. China's Titanic Peril: 2001 Update of the AIDS Situation and Needs Assessment Report. Beijing: UNAIDS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.State Council AIDS Working Committee Office, UN Theme Group on AIDS in China. A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China (2007) Beijing: China Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health of China, UNAIDS, WHO. The Estimation of HIV/AIDS in China in 2009. Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, Sullivan SG, Wang Y, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Detels R. Evolution of China's response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2007;369:679–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60315-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Harm Reduction Association . Global Statement on Harm Reduction. New York: International Harm Reduction Program (IHRD) of the Open Society Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiellin DA, O'Connor PG, Chawarski M, Pakes JP, Pantalon MV, Schottenfeld RS. Methadone maintenance in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:1724–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langendam MW, van Brussel GH, Coutinho RA, van Ameijden EJ. Methadone maintenance treatment modalities in relation to incidence of HIV: results of the Amsterdam cohort study. AIDS. 1999;13:1711–16. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward J, Hall W, Mattick RP. Role of maintenance treatment in opioid dependence. Lancet. 1999;353:221–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health, State Development Planning Commission, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Finance. China's Medium and Long-Term Plan on Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS. Beijing: Chinese Ministry of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.State Council of P.R. China. Action Plan on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Containment (2001–2005) Beijing: State Council of P.R. China; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pang L, Hao Y, Mi G, et al. Effectiveness of first eight methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S103–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304704.71917.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.State Council of P.R. of China. Regulations on AIDS Prevention and Treatment. Beijing: State Council of P.R. of China; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.State Council of P. R. China. China's Action Plan for Reducing and Preventing the Spread of HIV/AIDS (2006–2010) Beijing: State Council of P.R. of China; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.UNAIDS. High Coverage Sites: HIV Prevention Among Injecting Drug Users in Transitional and Developing Countries. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burrows D. Advocacy and coverage of needle exchange programs: results of a comparative study of harm reduction programs in Brazil, Bangladesh, Belarus, Ukraine, Russian Federation, and China. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:871–79. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000400025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Narcotic Control Commission. Annual National Narcotic Control Report 2009. Beijing: Ministry of Public Security; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu E, Liang T, Shen L, et al. Correlates of methadone client retention: a prospective cohort study in Guizhou province, China. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;20:304–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faggiano F, Vigna-Taglianti F, Versino E, Lemma P. Methadone maintenance at different dosages for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD002208. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C, Wu Z, Rou K, et al. Challenges in providing services in methadone maintenance therapy clinics in China: service providers' perceptions. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:173–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376:355–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu SY, Zeng FF, Huang GF, et al. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef gene sequences among inmates from prisons in China. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:525–29. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao S. Experimental Study on Improving Retention at Second Group of Methadone Maintenance Treatment Pilot Clinics in Sichuan Province. MPH Thesis. Beijing: National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin C, Wu Z, Rou K, et al. Structural-level factors affecting implementation of the methadone maintenance therapy program in China. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrell M, Ward J, Mattick R, et al. Methadone maintenance treatment in opiate dependence: a review. BMJ. 1994;309:997–1001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6960.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell J. Staff training in methadone clinics. In: Ward J, Mattick R, Hall W, editors. Methadone Maintenance Treatment and Other Opiod Replacement Therapies. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 361–78. [Google Scholar]