Abstract

Background Since 2007, sex has been the major mode of HIV transmission in China, accounting for 75% of new infections in 2009. Reducing sexual transmission is a major challenge for China in controling the HIV epidemic.

Methods This article discusses the pilot programmes that have guided the expansion of sex education and behavioural interventions to reduce the sexual transmission of HIV in China.

Results Commercial sex became prevalent across China in the early 1980s, prompting some health officials to become concerned that this would fuel an HIV epidemic. Initial pilot intervention projects to increase condom use among sex workers were launched in 1996 on a small scale and, having demonstrated their effectiveness, were expanded nationwide during the 2000s. Since then, supportive policies to expand sex education to other groups and throughout the country have been introduced and the range of targets for education programmes and behavioural interventions has broadened considerably to also include school children, college students, married couples, migrant workers and men who have sex with men.

Conclusions Prevention programmes for reducing sexual transmission of HIV have reasonable coverage, but can still improve. The quality of intervention needs to be improved in order to have a meaningful impact on changing behaviour to reducing HIV sexual transmission. Systematic evaluation of the policies, guidelines and intervention programmes needs to be conducted to understand their impact and to maintain adherence.

Keywords: HIV, sexual transmission, prevention, policy, implementation, China

Introduction

Sexual transmission of HIV is the single largest cause of new infections in China; 75% of the estimated 48 000 new infections in 2009 were via sex.1 In 2009, the Ministry of Health reported an even larger number of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs): 122 052 cases of gonorrhoea and 327 432 cases of syphilis.1 Several factors account for the rising numbers of STDs. There has been a recent, rapid increase in the numbers of female sex workers. Cultural norms in China have shifted towards greater sexual liberalization among youth amid a backdrop of a conservative administration that was initially very slow to react to the early warning signs of the impending STD epidemics. Finally, there has continued to be rapid migration from rural to urban cities, with adults typically migrating alone, rather than as a family.

This article reviews the intervention trials and policy changes relevant to the prevention of sexual transmission of HIV in China over the last two decades. The aim of this article is not to provide a systematic review of all condom intervention studies conducted in China to evaluate their effectiveness. Instead, we highlight only those studies, both published and unpublished, that have had a direct influence on policy, to describe those policies and the current state of their implementation and to discuss the challenges remaining.

China is at a point of transition between dogmatic and pragmatic policy; to some extent, policy has evolved informed by research, but ideology still obstructs their effective implementation. We hope this article will be informative for those wishing to understand the developments and limitations of policy development for the prevention of sexual transmission of HIV in China.

Early trials to prevent HIV among female sex workers (1996–2000)

Early attempts to control sexual transmission of HIV focused on female sex workers. Successful campaigns to eliminate the sex industry and STDs were conducted in the 1950s using re-education of sex workers and wide-scale treatment of STDs.2 These successes were reversed as the sex industry and STDs resurfaced in the late 1970s when China moved towards a market-based economy. This problem was recognized as early as 1983, but no formal policies were drafted at that time. Instead, STD education for sex workers was limited to programmes conducted in re-education through labour centres and some peer-outreach in the community. Neither of these approaches had much impact. Surveys conducted in the 1990s indicated low rates of condom use and very high rates of STDs—up to half had bacterial STDs.3

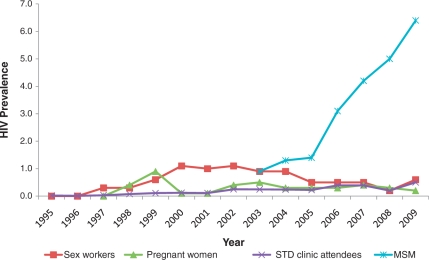

The Ministry of Health began monitoring the HIV epidemic among female sex workers in 1995 at 13 sentinel surveillance sites (Figure 1). The following year, the Chinese Academy for Preventive Medicine [now the Chinese Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC)] began exploring the feasibility of conducting a behavioural intervention study to promote condom use and increase HIV/STD awareness. With funding from the World Bank, the intervention was piloted in 1997 in three counties of Yunnan province, where China’s HIV epidemic is thought to have started. A total of 87 establishments each with 3–30 sex workers were chosen within the red-light districts of two counties and all establishments in the third county.4 Outreach workers visited the establishments six times to deliver lectures, show videos and hold discussions about HIV transmission and prevention, and to distribute condoms and educational leaflets. Establishment owners were also trained on the importance of ensuring that their staff used condoms, using videos and curricula developed in Thailand. After 3 months of intervention, evaluation of 297 participating women indicated increases in HIV knowledge from 25 to 88%, increases in perceived risk from 20 to 52% and increases in condom use at last sex from 61 to 85%.4

Figure 1.

The prevalence of HIV among sex workers at sentinel surveillance sites, 1995–2009. MSM = men who have sex with men. Note: The number of sentinel sites for commercial sex workers has increased, from 13 in 1995 to 434 in 2009

An important consideration in this trial was the intervention’s sustainability in the absence of reliable funding. At that time, government funds could not be guaranteed due to the socially controversial nature of interventions targeting sex workers. Thus, a self-sustaining intervention model was tested in Yunnan in 1999 with initial funding from the WHO.5 Its main aims were to increase condom usage and diagnosis and treatment of STDs. Two ‘Healthy Women Counselling and Service’ clinics were opened and the staff was trained to provide high-quality consultation and treatment for STDs in a non-stigmatizing manner. Two types of income generated from the programme were used to ensure sustainability. The first came from increased clinic revenue: although the clinics provided discounted services, patient numbers increased as a result of improved service delivery and quality, resulting in overall increased clinic income. The second source of funding came from the sale of discounted condoms. This two-pronged strategy not only reduced the transmission of STDs and HIV/AIDS but also created incentives for the clinics, strategies that would be adopted in later intervention trials.5

Expansion of interventions among female sex workers (2000–02)

The models developed in Yunnan were adapted and expanded into a five-city trial in 2000 in Anhui, Beijing, Fujian, Guangxi and Xinjiang, with funding from the World AIDS Foundation, and with the hope of developing a universal access model that would be applicable nationwide.6 These sites were chosen based on perceived need: all had an established HIV epidemic among injecting drug users and/or former commercial plasma donors, and it was feared that HIV would spread from these groups to female sex workers and into the general population. The programme identified a sexual health clinic in each city to provide sexual health services, counselling and HIV/STD testing. Educational resources were provided for clinic waiting rooms that discussed sexual health, reproductive health and HIV/STDs and their prevention. Outreach workers promoted 100% condom use by distributing condoms at a variety of establishments where sex workers worked. Condom use increased from 55% at baseline to 67% at 12 months after the intervention, the prevalence of gonorrhoea decreased from 26 to 4%, and chlamydia infection decreased from 41 to 26%.6

Around the same time, other programmes were also being piloted. Following the success of the 100% condom use programme in Thailand,7 a similar programme was developed to suit the Chinese context. The pilot programme began in Huangpi District of Wuhan City in Hubei Province, and Jingjiang County in Jiangsu Province, where it was estimated that between 1900 and 2500 sex workers were operating out of bathhouses, ‘barber shops’ and karaoke bars and where the public health system was well established and local officials supported the idea.8,9 Sex workers received educational and motivational outreach, peer education and information and education. Attempts were made to improve coordination between the STD services to monitor progress of the programme and regular meetings were held with establishment owners to discuss the programme.9 A year later, the programme evaluation indicated increases in condom use at last sex from 60 to 88% in Huangpi and from 55 to 91% in Jingjiang, as well as reductions in sexually transmitted infection rates in Huangpi from 8 to 1% for syphilis, from 3 to 0% for gonorrhoea and from 30 to 16% for chlamydia.8 Based on these successes, the programme was expanded to Li County in Hunan Province and Danzhou City in Hainan Province in 2002, and enjoyed even greater improvements in condom use.9 In 2003, a programme was also established in Liuzhou City, Guangxi Autonomous Region, with support from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).9

The World Bank Health-IX Loan Project was implemented in four provinces of China—Shanxi, Fujian, Xinjiang and Guangxi—in 1999–2008.10 One of its primary objectives was to explore innovative interventions and scale-up effective programmes to prevent and control HIV/AIDS/STDs. Female sex workers were among the most important target populations. Intervention elements followed the 100% condom use model and included outreach services based at STD clinics, with a focus on consistent condom use, regular check-ups, early diagnosis and treatment of STDs and other reproductive tract infections. The programme also tried to foster cross-sector cooperation and government cooperation with non-governmental organizations to create a more supportive policy environment. At the project’s end, women in project sites experienced significantly lower rates of STDs compared with those in non-project sites (24.8 vs 15.3%),10 although it cannot be ruled out that these differences occurred as a result of confounding or selection bias.

Although these behavioural interventions did not enjoy the same remarkable successes seen in Thailand and Cambodia,7,11 they were extremely valuable capacity-building exercises for local authorities and contributed to raising awareness about the health risks of sex work among the general public.9 Importantly, they convinced authorities that condom promotion in the commercial sex industry could have a substantial impact on controlling STDs, including HIV. Prior to 2000, policy and regulations for condom promotion were non-existent and their introduction was the subject of intensive dispute within the Chinese government. Similar to other countries, many policy-makers feared that promoting condoms would promote sex work and promiscuity. Evidence that condom promotion could be successfully adapted in China prompted the development of national guidelines for the implementation and expansion of the condom-use programmes among female sex workers.8

Policy framework

Early action plans to control HIV in China required public media to advocate HIV and STD prevention, and required educational institutions, such as high schools and universities, to teach students HIV/STD prevention knowledge.12 These programmes were supposed to focus on promoting positive attitudes on love, marriage and family, and sexual morality and sexual health and called for active promotion of condoms (however, as described later, the media was not permitted to promote condom use at that time). Concurrently, sex workers were to be educated on the laws governing prostitution and assisted with their rehabilitation in re-education through labour camps.3,12 Other legislation called for female sex workers to be directed to health authorities for HIV/STD testing13 and held them criminally liable for spreading HIV.14 In the absence of adequate funding and specific, structural guidance on how to carry out these tasks, it is not surprising that this early plan had little impact.15

China’s Medium-to-Long-term AIDS Plan (1998–2010) was superseded by China’s Action Plan for Reducing and Preventing the Spread of HIV/AIDS (2001–05).16 In addition to promoting condom use, advocacy and educational strategies, these policy documents added specific targets for evaluation—at least 50% of high-risk groups should use condoms. The policy documents also called for the installation of condom-vending machines in public places and enhanced social marketing of condoms by family planning associations and health bureaus.

Based on the successes of the interventions among female sex workers, in July 2004 the ‘Notice for Promotion of Condom Use to Prevent HIV/AIDS’ was issued by six ministries, including the State Administration for Radio Film and Television.17 This was a seminal item of legislation because prior to its issuance it had been forbidden for the mass media to advertise condoms;15 permission to do so, would widen the reach of condom promotion beyond the existing campaigns, which targeted high-risk groups, including sex workers, men who have sex with men (MSM) and migrant workers. The policy statements outlined the strategies, methods and relevant duties of related ministries for promoting condom use, and defined the responsibilities of provincial and national governments.

That same month, Premier Wen Jiabao issued a proclamation that emphasized the necessity for multi-sectoral cooperation in the AIDS response, a stronger focus on prevention among high-risk groups and the use of evidenced-based strategies to prevent further spread of HIV.18 This proclamation also called for crack-downs on ‘social evils’ including sex work, which is a contentious approach since it focuses on punishment rather than on education.19,20

Also in 2004, the State Council AIDS Working Committee issued a ‘Notice on HIV/AIDS Prevention Information, Education and Communication Guidelines (2004–2008)’. This document set out the principles for health education among various target groups, the roles and responsibilities of different government sectors on HIV/AIDS prevention and control and provided targets for the level of knowledge and attitudes to be achieved. A ‘Notice on Strengthening HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control in All Places for Re-education through Labour’ was also issued, which provided guidance for HIV/STD education in re-education through labour centres.

In August 2004, the Ministry of Health issued a notice to provincial health bureaus to ‘Establish a Task Force on Interventions among High-Risk Groups by Centres of Disease Control at All Levels’. In March 2005, the Ministry issued ‘High-risk Group Behavioural Intervention Guidelines’ to regulate the nationwide provision of interventions targeting high-risk groups. The guidelines confirmed that high-risk behavioural intervention teams should focus on controlling the sexual transmission of HIV, and this was the prologue to high-risk behavioural intervention work in sex work establishments nationwide. The notice specified the use of outreach as a key intervention strategy for reaching sex workers, in addition to condom promotion, regular health check-ups and early diagnosis and treatment of STDs and other reproductive tract infections.

In March 2006, China issued its first piece of legislation written for a specific disease, the ‘Regulations on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control’. These regulations include several articles that specifically call for condom promotion (Article 28) and provision (Articles 29 and 61) as a legal requirement, as well as requiring STD clinic staff to provide HIV/STD education to all patients (Article 12) and requiring all people living with HIV to notify their sexual partners of their HIV status (Article 38). The regulations actively promote interventions for the most-at-risk populations, defining these terms explicitly and calling for support and cooperation between government and civil society organizations. The accompanying ‘Five-year Action Plan for Reducing and Preventing the Spread of HIV/AIDS (2006–2010)’ called for multi-sectoral cooperation in the HIV response, including all of society, and emphasized the importance of prevention programmes and their monitoring and evaluation. The action plan sets out specific work goals and indicators according to practical measurements.

In August 2007, the Ministry of Health ordered all hotels, resorts and public bath houses in the country to provide condom-dispensing machines.21 This move alleviated the previous fear among bath-house owners of supplying condoms lest they be targeted by police for allowing lewd behaviour. In the following month, they also ordered these establishments to make their premises more accessible to public inspections by requiring massage rooms be viewed openly from outside and remain unlocked.

Large-scale promotion of sexual transmission interventions

Sex workers

In 2003, central government funds provided for condom promotion for sex workers in 351 counties.22 By 2009, 2862 counties were receiving funds for this purpose. The coverage of intervention programmes for female sex workers and their clients expanded to all counties by 2007, and roughly 462 000 sex workers had been reached by intervention programmes monthly by the third quarter of that year, with a monthly coverage of 39.8%.23 Annual funding for interventions to prevent sexual transmission of HIV continues to grow at both the national and provincial levels. The task of reaching sex workers with HIV prevention interventions has been taken on by a multitude of agencies, including various non-government organizations, government-affiliated organizations and international organizations. In addition, the Global Fund projects for rounds 3, 4, 5 and 6 have all included components aimed at reducing HIV risks among sex workers. Increasingly, more funds and new innovative programmes will be needed in the future as the demand for commercial sex increases along with the millions of men entering the marriage market who will be unable to marry due to China’s grossly distorted sex ratios.24

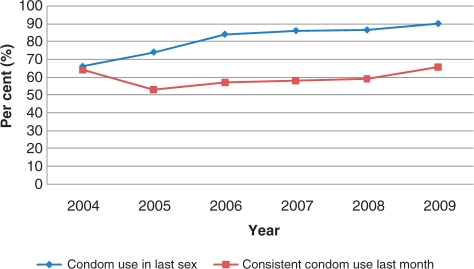

To monitor the epidemic among sex workers, sentinel surveillance has been increased to 434 sites. HIV prevalence among sex workers at sentinel surveillance sites in 2009 indicated that 0.4% were infected (593 of 145 867 sex workers were tested HIV positive, with median rate of 0%, prevalence range of 0–15.9%), while behavioural surveillance data suggested condoms were consistently used by only 41.4% of sex workers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Condom use among sex workers at behavioural surveillance sites, 2004–09

MSM

An important, and, until recently, neglected group at risk of HIV via sex is MSM. Surveillance among this group did not begin until 2002 and was limited to one site until 2005.25 Currently, there are 56 sentinel surveillance sites. By 2007, sentinel surveillance indicated that MSM accounted for a disproportionate number of new HIV infections in China—12.2%,23 although they are only estimated to comprise 3% of the total population of China.26 They are an important bridging population as many will marry women, but may continue to engage in risky sexual practises and may have higher rates of HIV than their unmarried counterparts.27 These observations prompted the development of guidelines on the conduct of behavioural interventions among this group in 2007. In 2008, a large-scale survey of HIV/AIDS prevalence and risk factors among MSM in 61 cities was initiated to better understand the rapidly increasing HIV prevalence among this group. Preliminary results indicate that ∼5% are positive for HIV and 11% for syphilis and consistent condom use is practised by ∼40% of respondents.28

The policy changes that were made in response to the sex worker epidemic and the HIV epidemic in general, as well as high rates of HIV/STDs among MSM, have established a base from which to call for the allocation of additional resources to fight HIV among this group. The risk appears high; therefore, there is less need for scientific evidence to persuade policy makers that interventions could work. Programmes targeting MSM have been included in Global Fund proposals. Concurrently, government funding has also increased to better understand and respond to the epidemic. Central government funds of 120 million yuan (∼USD 17.6 million) for both sex workers and MSM (who receive ∼25%, USD 4.4 million) have been allocated each year between 2007 and 2009. The funds set aside for MSM alone were 86 million yuan (∼USD 12.7 million) in 2010. Intervention programmes focusing on increasing condom use and HIV testing and counselling are primarily implemented by non-government organizations, particularly community organizations of MSM, with financial and technical support from local health sectors.

Sex work is illegal in China. However, sex between consenting men is not illegal in China. As a result, MSM differ considerably from sex workers in terms of the resources available to this subgroup. For example, it is risky for civil society organizations to work with groups engaging in illegal behaviours, such as sex work. Thus, there are fewer organizations and fewer powerful organizations able to advocate for the rights of sex workers. In contrast, ‘gay’ communities are relatively well organized and have established civil society groups to serve their communities. Moreover, the government has developed strong partnerships with gay civil society organizations to implement intervention programmes among MSM. Throughout the development of national guidelines, civil society groups working on this issue were consulted, and many of the city-level CDCs have forged partnerships with local community groups to aid the implementation of interventions among MSM. This kind of consultation was not done for the other major risk groups that engage in illegal acts (sex workers or injecting drug users).

A neglected subgroup are men who sell sex to men and women. This population is increasing, as demand for sex by men and women from men increases. However, as with female sex workers, condom use is low and STD rates are high.29,30 One of the major difficulties in developing interventions for this group is that many do not identify as homosexual, so they may ignore health education programmes targeting gay men29 and may also ignore condom promotion targeted at female sex workers.

Migrant workers

Migrant workers comprise roughly 130 million people in China, more than half of whom are men. They are a recognized risk group for HIV and other STDs because many spend long periods away from their spouse, and may purchase, and in some cases sell, sex while away from home.31–33 Although many engage in these high-risk behaviours, they may perceive they are at low or no risk of HIV and other STDs. Moreover, wives left behind by migrant husbands may also engage in more high-risk behaviours than their counterparts whose husbands are not migrants.34 Thus, one of the goals targeted in the 2006–10 Action Plan was that 70% of the migrant population should be reached by educational interventions and understand HIV transmission and prevention.35 However, specific guidelines on conducting interventions among migrant workers have not been developed; thus, no wide-scale interventions exist. Some short-term education programmes are launched during holiday periods when many migrants travel back to their home towns, but their impact has not been evaluated.

Youth

Youth in China are becoming increasingly sexually active, but often have low rates of condom use and poor HIV awareness.36,37 Since STD/HIV rates among youth are not specifically monitored by surveillance, current knowledge about this group is based on sporadic surveys that are of limited use to policy makers, who require serial surveys. Although several small-scale trials have been mounted to increase condom use among youth, the results have not been considered in development of policy initiatives.

The ‘AIDS Regulations’ require all educational institutions provide their students with sex education (Article 13)38 and the 2006–10 5-Year Action Plan requires by the end of 2010 that 95% of school students and 75% of out-of-school youth to have HIV transmission and prevention knowledge. The guidelines also require schools, colleges and universities to provide sex education classes.35 The Ministry of Education has developed guidelines for sex education programmes in schools, but there has been no systematic evaluation of whether the targets set out in the 5-Year Plan have been met.

An important component of the HIV response is education and the responsibility for educating students often rests with teachers who are too shy or ignorant to teach sex education. As Chinese youth become more sexually liberated, the need to teach them how to have safe sex becomes more urgent. Training for these teachers to overcome barriers to teaching about sex can help improve the quality of sex education in schools.39 Sustained programmes uniformly implemented across the education system are needed since cursory campaigns to increase condom use among youth may have limited long-term impacts.40

Out-of-school youth are a difficult population to reach and there are no guidelines on how to conduct interventions among them. Therefore, education should be implemented in the earlier grades before they drop out of school. There are, however, many international trials that could provide models for China to adapt.

Sero-discordant couples

A substantial number of Chinese people living with HIV were infected via non-sexual routes, and even among those who were infected sexually, their spouse remains at risk of HIV infection. This is particularly true in the provinces where infection occurred largely through illegal and unsafe blood and plasma donations.41 To address this issue, a comprehensive framework for reducing intra-marital transmission of HIV/AIDS was developed and includes: enhanced management of infected persons; adequate follow-up of known infections; the provision of a series of comprehensive interventions and ensuring relevant government agencies take responsibility for meeting performance targets; intensified voluntary counselling and testing in order to detect infections; ensuring informed consent is used in HIV testing results in high prevalence areas; and adopting appropriate procedures for informing infection’s status of sex partners.

Challenges

Nationwide, the interventions targeting the sexual transmission of HIV/AIDS have been evolving and improving in quality over time. Yet, many challenges remain. First and foremost, the government’s regulations, notices and laws to combat the sexual transmission of HIV have been enforced variably. There has been inadequate evaluation of their impact. Examination of sentinel surveillance data do not suggest declines in the HIV epidemics of major risk groups. The existing government data suggest a stabilizing of risk behaviours, rather than any notable reductions (Figures 1 and 2). The Ministry of Health is planning to launch a proper evaluation of the impact of the AIDS regulations and to enforce the consequences of not following the regulations. Without a consistent evaluation of the targeted goals, the government risks appearing to have issued these regulations for the sake of appearance rather than action.

In some areas and sectors of government, there is insufficient awareness of the importance and urgency for interventions among the most at-risk populations, which means these interventions receive limited support and attention. This results in interventions being less effective than they could be. This problem may be attributed to insufficient training for local staff, to help them understand the gravity of the situation and to their own stigmatizing attitudes. Stigmatizing attitudes may lead providers to assign low priority to these tasks (particular prevention among stigmatized groups). Increased attention to and allocation of resources for training of local staff could improve their attitudes towards prevention work.

The coverage and quality of recommended interventions are still limited and some areas cannot provide specific services. Although funding has increased over the years to address HIV work, the tasks are among the many that over-stretched health workers must do in their daily work and may not be prioritized. Improving training, assigning manageable workloads and improving workplace benefits can have positive impacts on staff outputs.42

Education for sex workers is made difficult by the high turnover of women working in the profession. Establishments need to be monitored, as they are in Thailand, to ensure managers are continuously providing the requisite education. Greater cooperation from police is also needed to ensure this, but police cooperation is complicated by their own mandates.20

Sex education provided by penal institutions is extremely limited.20 There is evidence that incarcerated sex workers have higher rates of HIV/STDs than non-incarcerated sex workers.43 The continued use of incarceration to ‘rehabilitate’ sex workers as well as other methods of public shaming are counterproductive to HIV/STD control and should be revised.

Civil society organizations have played a crucial role in the expansion of condom promotion and sex education programmes around the country, but they often lack sufficient, experienced and well-trained personnel. Further staff training for these organizations is imperative. These organizations also have limited access to funding and a complicated registration process that has recently been made even more difficult by shifts in funding policies.44 Outside of programmes for MSM, cooperation between civil society groups and government has generally been limited, despite the merits of civil society involvement in prevention work. Non-government organizations are typically more trusted by target groups and can engage in work that is too controversial for the government.45 The often precarious status of non-registered civil society groups can make them targets by police, particularly if the agency serves people engaging in illegal behaviour, such as sex work. This results in a lack of trust in the organizations conducting intervention work, making programmes less effective.45 These problems will persist until the rules regarding the registration of non-governmental organizations are revised and independent sources of funding can be secured.

Serious stigma still impedes the efficacy of interventions. The perceived immorality of sex work, promiscuity and sex between men clouds the acceptance of behavioural interventions for these groups and limits public health education. Stigma from law enforcement officials, particularly during crackdowns, can impede intervention work and lead to distrust among those being served. Overcoming stigma has been repeatedly cited as key to overcoming the epidemic and requiring input from all of society, as well as cooperation from multiple ministries. However, wide-scale, long-term multi-sectoral campaigns to address stigma are still lacking.

Conclusions

Significant progress has been made in China’s attempts to avert the sexual HIV epidemic. Interventions among sex workers and, more recently, MSM, have been driven by an evidence-based scientific approach. These have guided the development of policy and legislation that supports interventions to reduce the sexual spread of HIV. Implementation of these approaches is still hampered, however, by substantial stigma towards those most at-risk, insufficient appreciation for the seriousness of the situation among some of the responsible government departments and the limitations of both government and civil society groups. The high proportion of new HIV infections caused by sexual contact has alerted authorities of the need to prioritize this mode of transmission. Strong commitment and a problem-solving-oriented approach will allow China to better address this new challenge.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chinese Ministry of Health National AIDS Programme (131-08-105-02); partly supported by China National Science and Technology Major Project on AIDS (2008ZX10001-016); and partly supported by the Multidisciplinary HIV and TB Implementation Sciences Training in China funded by the US National Institute of Health, Fogarty International Center and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (China ICOHRTA2, NIH Research Grant 5U2R TW06918-07, Principal Investigator Z.W.). S.G.S. was partially supported by a UC Pacific Rim Research Program Minigrant.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lu Wang for providing surveillance data to create two figures and Mary-Jane Rotheram and Roger Detels for their editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest: Z.W. and K.R. were involved in the early intervention trials described in this article. Z.W. is the director of the National Centre for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention at Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

KEY MESSAGES.

Prevention programmes for reducing sexual transmission of HIV have been significantly improved and reached a reasonable coverage in China.

The quality of intervention needs to be improved in order to have a meaningful impact in reducing HIV sexual transmission.

References

- 1.National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention. Annual Report on HIV/AIDS/STD Epidemiology, Prevention and Treatment in China in 2009. Beijing: China CDC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Henderson GE, Aiello P, Zheng H. Successful eradication of sexually transmitted diseases in the People's Republic of China: implications for the 21st century. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:S223–29. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_2.s223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gil VE, Wang MS, Anderson AF, Lin GM, Wu ZO. Prostitutes, prostitution and STD/HIV transmission in mainland China. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:141–52. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z, Rou K, Jia M, Duan S, Sullivan SG. The first community-based sexually transmitted disease/HIV intervention trial for female sex workers in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S89–94. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304702.70131.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z. Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Sustainability of STD/HIV Interventions with Female Attendants at Entertainment Establishments in Yunnan, China (unpublished report) Beijing: Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rou K, Wu Z, Sullivan SG, et al. A five-city trial of a behavioural intervention to reduce sexually transmitted disease/HIV risk among sex workers in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304703.77755.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rojanapithayakorn W, Hanenberg R. The 100% condom program in Thailand. AIDS. 1996;10:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO . Experiences of 100% Condom Use Programme in Selected Countries of Asia. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO, China CDC . 100% Condom Use Programme: Experience from China (2001-2004) http://www.chain.net.cn/english/wArticle.php?articleID=7924. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J. Investigation of STI Prevalence of SWs to Evaluate the World Bank Health IX HIV Intervention Program in China. International AIDS Conference, 2008; Mexico; Manila: WHO Western Pacific Regional Office, 2008. p. Abstract No. TUPE0347. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rojanapithayakorn W. The 100% condom use programme in Asia. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14:41–52. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health, State Development Planning Commission, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Finance. Medium and Long-Term Plan on Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS. Beijing: State Council of PR China; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Surveillance and Control Measures Applicable to AIDS. Beijing: 1988. p. 623. Section 15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. Frontier Health and Quarantine Law. Beijing: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen J, Yu D. Governmental policies on HIV infection in China. Cell Res. 2005;15:903–07. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.State Council of P.R. China. Action Plan on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Containment (2001–2005) Beijing: State Council Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health, National Population and Family Planning Commission, State Food and Drug Administration, State Administration for Industry and Commerce, State Administration of Radio Film and Television, General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine. Notice for Promoting Condom Use for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control. Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen J. Joint Efforts for Effective Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS. Beijing: State Council of PR China; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson AF. China Report: AIDS, law, and social control. Int J Off Ther Compare Criminol. 1991;35:303–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu H, Choy DW. Administrative detention of prostitutes: the legal aspects. In: Poston DL, Tucker J, Ren Q, et al., editors. Gender Policy and HIV in China. The Netherlands: Springer; 2009. pp. 189–99. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J. China Daily. Beijing: China Daily; 2007. Tighter rules on bath houses, massage parlors. Available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-09/01/content_6073061.htm (date last accessed 27 October 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Z, Sullivan S, Rotheram-Borus M, Li L, Detels R. China. In: Celentano D, Beyrer C, editors. Public Health Aspects of HIV/AIDS in Low and Middle Income Countries: Epidemiology, Prevention and Care. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 375–400. [Google Scholar]

- 23.State Council AIDS Working Committee Office, UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China. A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China (2007) Beijing: China Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker JD, Henderson GE, Wang TF, et al. Surplus men, sex work, and the spread of HIV in China. AIDS. 2005;19:539–47. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163929.84154.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun X, Wang N, Li D, et al. The development of HIV/AIDS surveillance in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S33–38. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304694.54884.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. China Daily. Chinese gay population announced for the first time. China Daily. 5 April 2006.

- 27.Feng L, Ding X, Lu R, et al. High HIV prevalence detected in 2006 and 2007 among men who have sex with men in China’s largest municipality: an alarming epidemic in Chongqing, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:79–85. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a4f53e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Liu E, Mi G, et al. HIV, Syphilis, HCV and HSV-2 Prevalence among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Urban China. XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, 18–23 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai WD, Zhao J, Zhao JK, et al. HIV prevalence and related risk factors among male sex workers in Shenzhen, China: results from a time-location sampling survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:15–20. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mi G, Wu Z. Male commercial sex workers and HIV/AIDS. China J AIDS STD. 2003;9:252–53. [Google Scholar]

- 31.He N, Wong FY, Huang ZJ, et al. HIV risks among two types of male migrants in Shanghai, China: money boys vs. general male migrants. AIDS. 2007;21:S73–79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304700.85379.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson AF, Qingsi Z, Hua X, Jianfeng B. China’s floating population and the potential for HIV transmission: a social-behavioural perspective. AIDS Care. 2003;15:177–85. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He N, Detels R, Chen Z, et al. Sexual behavior among employed male rural migrants in Shanghai, China. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:176–86. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong H, Qin QR, Li LH, Ji GP, Ye DQ. Condom use among married women at risk for sexually transmitted infections and HIV in rural China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;106:262–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.State Council of P.R. China. China’s Action Plan for Reducing and Preventing the Spread of HIV/AIDS (2006–2010) Beijing: State Council Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan H, Chen W, Wu H, et al. Multiple sex partner behavior in female undergraduate students in China: a multi-campus survey. BMC Pub Health. 2009;9:305. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Q, Ono-Kihara M, Cong L, et al. Behavioral and psychosocial predictors of condom use among university students in Eastern China. AIDS Care. 2009;21:249–59. doi: 10.1080/09540120801982921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.State Council of P.R. China. Regulations on AIDS Prevention and Treatment. Beijing: State Council Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hausman AJ, Ruzek SB. Implementation of comprehensive school health education in elementary schools: focus on teacher concerns. J Sch Health. 1995;65:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1995.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu X, Lou C, Gao E, Shah IH. Long-term effects of a community-based program on contraceptive use among sexually active unmarried youth in Shanghai, China. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Z, Sun X, Sullivan SG, Detels R. Public health. HIV testing in China. Science. 2006;312:1475–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1120682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaye PA, Nelson D. Effective scale-up: avoiding the same old traps. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tucker JD, Ren X. Sex worker incarceration in the People’s Republic of China. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:34–35. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027235. discussion 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen G. China’s nongovernmental organizations: status, government policies, and prospects for further development. Int J Not-for-Profit Law. 2001;3 Available at: http://www.icnl.org/KNOWLEDGE/ijnl/vol3iss3/art_2.htm (date last accessed 27 October 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu H, Zeng Y, Anderson AF. Chinese NGOs in action against HIV/AIDS. Cell Res. 2005;15:914–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]