Abstract

AIM: To investigate chronic stress as a susceptibility factor for developing pancreatitis, as well as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) as a putative sensitizer.

METHODS: Rat pancreatic acini were used to analyze the influence of TNF-α on submaximal (50 pmol/L) cholecystokinin (CCK) stimulation. Chronic restraint (4 h every day for 21 d) was used to evaluate the effects of submaximal (0.2 μg/kg per hour) cerulein stimulation on chronically stressed rats.

RESULTS: In vitro exposure of pancreatic acini to TNF-α disorganized the actin cytoskeleton. This was further increased by TNF-α/CCK treatment, which additionally reduced amylase secretion, and increased trypsin and nuclear factor-κB activities in a protein-kinase-C δ and ε-dependent manner. TNF-α/CCK also enhanced caspases’ activity and lactate dehydrogenase release, induced ATP loss, and augmented the ADP/ATP ratio. In vivo, rats under chronic restraint exhibited elevated serum and pancreatic TNF-α levels. Serum, pancreatic, and lung inflammatory parameters, as well as caspases’activity in pancreatic and lung tissue, were substantially enhanced in stressed/cerulein-treated rats, which also experienced tissues’ ATP loss and greater ADP/ATP ratios. Histological examination revealed that stressed/cerulein-treated animals developed abundant pancreatic and lung edema, hemorrhage and leukocyte infiltrate, and pancreatic necrosis. Pancreatitis severity was greatly decreased by treating animals with an anti-TNF-α-antibody, which diminished all inflammatory parameters, histopathological scores, and apoptotic/necrotic markers in stressed/cerulein-treated rats.

CONCLUSION: In rats, chronic stress increases susceptibility for developing pancreatitis, which involves TNF-α sensitization of pancreatic acinar cells to undergo injury by physiological cerulein stimulation.

Keywords: Pancreatitis, Stress, Tumor necrosis factor-α

INTRODUCTION

Stress can be defined as “threatened homeostasis”. Stressors can include physical or mental forces, or combinations of both. The reaction of an individual to a given stressor involves the stimulation of pathways within the brain leading to activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the central sympathetic outflow[1]. These can result in visceral hypersensitivity through the release of different substances, such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide from afferent nerve fibers[2].

While it is well established that a previous acute-short-term stress decreases the degree of severity of pancreatitis in several experimental models[3,4], the effects of chronic stress on the exocrine pancreas have received relatively little attention[5,6]. Chronic stress has been proved to increase the susceptibility of different rat organs, such as the small intestine, colon, and brain, to inflammatory diseases[2,7-9], as well as to aggravate atherosclerotic lesions in mice[10].

The pro-inflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), has an important role in various biological functions, including cell proliferation, cell differentiation, survival, apoptosis and necrosis[11], and in stress-related inflammatory disorders[8-10,12]. Secretion of TNF-α by several stressful stimuli has been demonstrated in many cell types, including pancreatic acinar cells[13-20]. Previous reports evaluated the response of pancreatic acinar cells to exogenous TNF-α, showing disruption of the actin cytoskeleton and activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), a key transcriptional regulator of the expression of inflammatory molecules[21-23]. Interestingly, this TNF-α activation of NF-κB is mediated by the novel protein kinase C δ (PKCδ) and PKCε[23], which have also been shown to modulate cerulein-induced zymogen activation in these cells[24]. Although TNF-α has been shown to participate in the inflammatory cascade that propagates pancreatitis[25], its relevance in the genesis of this multifactor disease was hardly investigated.

We examined the possibility that chronic stress is a susceptibility factor for developing pancreatitis and that TNF-α is a putative sensitizer. We performed studies on both in vitro dispersed rat pancreatic acini stimulated with TNF-α and submaximal doses of cholecystokinin (CCK), and in in vivo rats under chronic stress induced by restraint and challenged with submaximal doses of the CCK-analogue cerulein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies used include those against rat TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), Na+/K+ ATPase (Upstate Biotechnology-Chemicon Int., Temecula, CA), PKCδ and PKCε (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and tubulin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin was from Molecular Probes (Burlington, ON, Canada). Recombinant TNF-α was from R&D Systems. Sulfated CCK octapeptide, cerulein, Hoechst dye 33258, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, and o-dianisidine hydrochloride were from Sigma Chemical Co. Calphostin C, and Gö6976 were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). PKCζ myristolated pseudosubstrate inhibitor was from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). The PKCδ-specific antagonist peptide δV1-1was synthesized by American Peptide Company, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA) and conjugated to a TAT peptide (PKCδ translocation inhibitor δV1-1). PKCε translocation inhibitor εV1-2 was from Anaspec (San Jose, CA). The protease inhibitor cocktail was from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). BoC-Glu-Ala-Arg-MCA was from Peptides International (Louisville, KY). Amylase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), glucose, urea, creatinine, calcium, total proteins, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and quantitative C-reactive protein assay kits were from Wiener Lab (Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina). The lipase assay kit was from Randox Laboratories Ltd. (Antrim, UK). NF-κB (p65), NF-κB (p50) transcription factor, lipid hydroperoxide (LPO), and malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay Kits were from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). TNF-α and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) Kits were from R&D Systems. The hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) Kit was from Genxbio Health Science (Delhi, India). The protein assay kit was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The heat shock protein (HSP) 72 Kit was from StressGen Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA). PKCδ and PKCε Kinase Assay Kits were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 Kits were from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI). The CasPASE Apoptosis Activity Assay Kit was from Genotech (Maryland Heights, MO). The Enliten ATP Assay Kit was from Promega (Madison, WI). The ApoSensor ADP/ATP Ratio Assay Kit was from Enzo Life Science International Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Animal model

Male Wistar rats (200-250 g) were housed in standard cages in a climate-controlled room with a temperature of 23 ± 2°C and a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08.00 h), with free access to food and water except during restraint times. All animals were maintained under constant conditions for 4 d prior to stress, and they were randomly assigned to non-stress (control) or stress groups. Every day at 09.00 h, animals from both non-stress and stress groups received either 50 μg/kg TNF-α-neutralizing antibodies or an equal dose of control IgG, given as intraperitoneal (ip) injections. Rats in the stress group were exposed to various sessions of restraint (4 h every day for 21 d) between 10.00 and 14.00 h in the animal homeroom. The immobilization was performed using a metallic restraint jacket and was placed inside their home cage during the restraint sessions. Control rats were handled once at 10.00 h for few seconds and left undisturbed in their home cages. Food and water were removed from their cages to avoid their interference in the parameters determined. Following the 21 d stress protocol, rats from each condition, non-stress (-) and stress (+), were then randomly distributed into three groups of four rats each. One group was treated with six doses of saline-vehicle (Veh groups), and the other two groups were treated with six doses of 0.2 μg/kg cerulein (Cer groups and anti-TNF-α plus Cer groups), given as hourly ip injections. Rats were sacrificed 1 h after the last injection by decapitation, and blood was drained onto heparinized dishes for white blood cell count and determination of hematocrit. Amylase (end-point colorimetric method), lipase (UV turbidimetric method), TNF-α [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)], LDH (German Society of Clinical Chemistry-DGKC optimized kinetic method), glucose (enzymatic method), urea (enzymatic method), creatinine (end-point colorimetric method), calcium (direct colorimetric method), total proteins (enzymatic method), AST and ALT (IFCC optimized UV method), C-reactive protein (immunoturbidimetric method), HSP-72 (ELISA assay), IL-6 (ELISA assay), IL-10 (ELISA assay), and MIP-1α (ELISA assay) levels were assessed in serum using the respective assay kits. Pancreatic and lung tissues were obtained for determination of levels of NF-κB (p65) and NF-κB (p50) in nuclear extracts, and TNF-α using the respective ELISA assay kit, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. Pancreatic tissue was also evaluated for levels of HIF-1α (ELISA assay), LPO and MDA (colorimetric method) using the respective assay kit, and trypsin activity. Caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9 activity (colorimetric/fluorometric method), and ADP and ATP levels (bioluminescent method) were determined in pancreatic, lung, and stomach tissue using the respective assay kits. All kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the CBRHC Research Center.

Dispersed acini preparation

The preparation of isolated pancreatic acini from rats was performed by a mechanical and enzymatic dissociation technique[26]. The acini were resuspended in oxygenated Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) buffer, consisting of (in mmol/L): 104 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 0.2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 0.01% (wt/vol) soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 glucose, and 25 2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)/NaOH, pH 7.4, supplemented with minimal essential and non-essential amino acid solution and glutamine.

Cellular models

Hypoxia and reoxygenation treatment: Isolated pancreatic acini were seeded in six-well plates. The hypoxia and reoxygenation (H/R) media were produced by equilibrating Krebs-Henseleit buffer, consisting of (in mmol/L): 118.3 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 25.0 NaHCO3, and 11.0 glucose, pH 7.4, in 95% N2/5% CO2 or 95% air/5% CO2, respectively. The studies were carried out using two water-jacketed incubators at 37°C as follows. For H/R treatment, acini were exposed to an anoxic gas mixture (95% N2/5% CO2) in a humidified incubator for 30 min. After the hypoxia period, hypoxic media was rapidly replaced with reoxygenation media and the acini were transferred to 95% air/5% CO2 in a humidified incubator for 3 h. For normoxia (N) control treatment, acini were exposed to 95% air/5% CO2 in a humidified incubator for the same period of time as the H/R samples. To determine the effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibition, NAC (30 mmol/L) was added to the cells 1 h before hypoxia, and it was maintained in the media throughout the experiment. TNF-α released into the supernatant was determined using an ELISA assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Values were normalized by DNA content in each sample, which was measured using Hoechst dye 33258.

Hydrogen peroxide stimulation: Isolated pancreatic acini were seeded in six-well plates and incubated with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 50 μmol/L) for 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. To determine the effect of ROS inhibition, NAC (30 mmol/L) was added to the cells 1 h before H2O2, and it was maintained in the media throughout the experiment. TNF-α released into the supernatant was determined by the corresponding ELISA assay kit and values were normalized by DNA content in each sample.

TNF-α and CCK stimulation: Isolated pancreatic acini were stimulated with CCK (50 pmol/L) for 1 h at 37°C. Pretreatment with the indicated concentrations of TNF-α in KRH was performed for 1 h prior to and along stimulation. Levels of amylase and LDH release, NF-κB (p65) and NF-κB (p50) in nuclear extracts, caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9 activity, and ADP and ATP, were measured in pancreatic acini using the respective assay kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Acini were also assessed for trypsin activity.

Amylase secretion: Amylase released into the supernatant and amylase content of the acini pellet were determined by a colorimetric method as previously reported[27]. “Total amylase” is defined as the summation of the amylase content in the respective cell pellet plus supernatant, and the amylase secreted into the supernatant is expressed as a percentage of total amylase.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy: Dispersed acini were placed on glass coverslips and after indicated treatments fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed coverslips were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, followed by incubation with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. Acini were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin (1:500) for 1 h at 25°C. Coverslips were examined with a 63 × oil immersion objective and conventional laser excitation and filter set, by a laser scanning confocal imaging system (Zeiss LSM510) equipped with the LSM software version 5.00 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Subcellular fractionation and immunoblotting

Subcellular fractionation: Isolated pancreatic acini, after equilibration (20 min, 37°C), were subjected to the indicated stimulation, and then terminated by adding an excess volume of ice-cold KRH buffer. The acini were then pelleted by centrifugation (300 g, 4°C). Whole cell lysates and purified membranes were prepared from the treated dispersed acini by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Briefly, the sucrose buffer consisted of: 0.3 mol/L sucrose, 0.01% soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.5 mol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, and 5 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol. The acini were homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer, followed by a five min centrifugation (14 000 g, 4°C) to separate the nuclei pellets from supernatants. The supernatant fractions were centrifuged (15 min, 14 000 g, 4°C) to separate the zymogen granule pellets, and the resulting supernatants subjected to ultracentrifugation (3 h, 93 000 g, 4°C) to obtain the membrane pellet and cytosol supernatant fractions.

Immunoblotting: The protein contents of all samples were determined by Bradford method. Samples of subcellular fractions were dissolved in Laemmli buffer and boiled for five min. Equal amounts of protein were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Blots were blocked for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline containing 5% bovine serum albumin and then incubated with the corresponding primary antibody. The bound antibody was visualized by relevant peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies using the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Quantification was performed by densitometry using the NIH-Image software.

Isoform-specific PKC activity

PKCδ and ε activities were determined on lysates from isolated acinar cells using the respective ELISA assay kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Activity values were normalized to the basal activity in non-stimulated control cells.

Trypsin activity

Pancreatic tissue and pancreatic acini samples were pelleted, and the cell pellet was resuspended in ice-cold morpholino propylsulfonate (MOPS) buffer, pH 7.0 (containing in mmol/L: 250 sucrose, 5 MOPS, and 1 MgSO4), and then homogenized by hand using a Teflon and glass homogenizer. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was used for the assay. Trypsin activity was measured fluorometrically in a stirred cuvette at 37°C in a Hitachi F-2000 spectrofluorometer with excitation at 380 nm and emission at 440 nm, using BoC-Glu-Ala-Arg-MCA as the substrate. Briefly, the slope of rising fluorescence emission was calculated as arbitrary units and normalized per DNA content in the homogenate of each sample.

Caspases’ activity

Caspase 2, 3, 8, and 9 were measured using a colorimetric/fluorometric method as previously reported[28]. Briefly, pancreatic, lung or stomach tissue, or pancreatic acinar cell samples were homogenized in chilled lysis buffer and the lysates were centrifuged at 15 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Caspases’ activity was assessed on the supernatants.

ATP and ADP levels

ATP and ADP were measured using a bioluminescent method, as previously reported[28]. Briefly, pancreatic, lung, or stomach tissue, or pancreatic acinar cell samples were homogenized in 6% TCA (trichloroacetic acid) for one min and centrifuged at 6000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The TCA in the supernatant was neutralized and diluted to a final concentration of 0.1% with Tris-Acetate buffer, pH 7.75. ATP and ADP were measured in the supernatant. ATP loss was calculated as a percentage of the decrease in values corresponding to control.

MPO activity

Pancreatic and lung tissue were analyzed for MPO activity. Briefly, approximately 50 mg of pancreatic or lung tissue was homogenized on ice with 1 mL of 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide in 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer-pH 6.0. The homogenate was sonicated for 10 s at 200 W, and then centrifuged at 40 000 g for 15 min at 4°C. MPO activity in the supernatant was assayed as follows: 0.1 mL of supernatant was combined with 2.9 mL of 5 mmol/L phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 0.167 mg/mL o-dianisidine hydrochloride, and 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide. The change in absorbance at 460 nm was measured spectrophotometrically. One unit of MPO activity is defined as the amount that degrades 1 μmol of peroxide per minute at 25°C. MPO activity was normalized by DNA content in the homogenate of each sample.

Extraction of DNA

The total mass of DNA in the homogenate of each sample was used to standardize the units of enzymatic activity. Approximately 50 mg of tissue was homogenized in 400 μL of lysis buffer consisting of 0.5% SDS, 0.1 mol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris pH 8, 2.5 mmol/L EDTA, and 100 μg/mL proteinase K, for 1 h at 63°C and 650 r/min. Seventy-five microliters of 8 mol/L potassium acetate followed by 500 μL of chloroform were then added. Samples were frozen at -20°C for 15 min and centrifuged at 10 000 r/min for 5 min at 4°C. The DNA was extracted in 1 mL of absolute ethanol and washed in 1 mL of 70% ethanol. The clean DNA pellet was resuspended in distilled water buffer and DNA was measured at 260 nm.

Histological evaluation

Pancreatic, lung, and stomach tissues were graded on a scale of 0 to 4 each for edema, hemorrhage, leukocyte infiltrate, and necrosis. Histological changes were scored in a blinded manner by two independent observers counting frequency of foci per field seen at 40 × (absent, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; severe, 3; overwhelming, 4).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SE. The data for each group were subject to analysis of variance followed by Dunnet post hoc test when comparing three or more groups, or evaluated using Student’s t-test when comparing only two groups. Significant differences were considered with values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

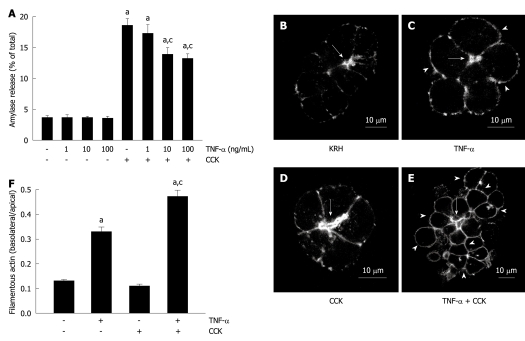

TNF-α reduces submaximal CCK-stimulated amylase secretion

We first examined the effects of TNF-α on amylase secretion from dispersed rat pancreatic acini. Different samples were incubated with different concentrations of TNF-α. Figure 1A shows that none of them stimulated amylase release (3.6% ± 0.5%, 3.5% ± 0.4% and 3.4% ± 0.5% for 1, 10 and 100 ng/mL, respectively) over basal vehicle-control levels (3.6% ± 0.4%). However, two TNF-α concentrations inhibited 50 pmol/L CCK-stimulated secretion (13.8% ± 1.2% and 13.1% ± 0.9% for 10 and 100 ng/mL), which, when compared to CCK alone (18.5% ± 1.2%), represent a reduction of 25.4% and 29.2%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Tumor necrosis factor-α disorganizes the actin cytoskeleton and reduces submaximal cholecystokinin-stimulated amylase secretion. A: Amylase secretion from pancreatic acini. Isolated pancreatic acini were stimulated with either the indicated concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for 2 h, or 50 pmol/L cholecystokinin (CCK) for 1 h, or the indicated concentrations of TNF-α for 1 h followed by the indicated concentrations of TNF-α plus 50 pmol/L CCK for 1 h, or Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) (vehicle-control) for 2 h. Amylase secreted into the media was determined and expressed as a percentage of the total cellular amylase of the respective sample. Results correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05 vs KRH; cP < 0.05 vs CCK alone; B-F: Filamentous actin distribution; B-E: Confocal images of filamentous actin localization in pancreatic acinar cells. Isolated pancreatic acini were treated with either KRH for 2 h (B), or 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 2 h (C), or 50 pmol/L CCK for 1 h (D), or 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 1 h followed by 10 ng/mL TNF-α plus 50 pmol/L CCK for 1 h (E). Fixed and permeabilized acini were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin. Arrows show apical lumens, and arrowheads show basolateral membranes. These are representative images selected from three independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate; F: Quantification of filamentous actin distribution. Areas of the apical and basolateral membranes in acinar cells treated as in B-E were delineated and the fluorescence intensity was determined. Sixty cells from three independent experiments were analyzed per condition. Values correspond to the intensity in the basolateral area vs the apical area, and are expressed as the mean ± SE. aP < 0.05 vs KRH; cP < 0.05 vs TNF-α alone.

TNF-α-induced actin cytoskeleton disorganization is increased during CCK stimulation

TNF-α has been shown to cause actin disorganization in isolated pancreatic acini, which is distinguished by increased filamentous actin along the basolateral membranes and its decrease in the apical area[21]. Here, we showed that both KRH vehicle-control and CCK-stimulated pancreatic acini exhibited the typical actin staining, intense in the apical area, and little and weak in the basolateral area of the acinar cell (Figure 1B and D). However, both 10 ng/mL TNF-α- and 10 ng/mL TNF-α plus 50 pmol/L CCK-stimulated acini exhibited the previously described actin disorganization pattern, which was more pronounced in acini challenged with TNF-α plus CCK (Figure 1C and E). This disorganization was also observed when using 100 ng/mL, but not with 1 ng/mL TNF-α alone or together with CCK (data not shown). Figure 1F shows the quantification of actin distribution (0.13 ± 0.01, 0.11 ± 0.01, 0.33 ± 0.02 and 0.47 ± 0.03 basolateral/apical actin ratio for KRH, CCK, TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively).

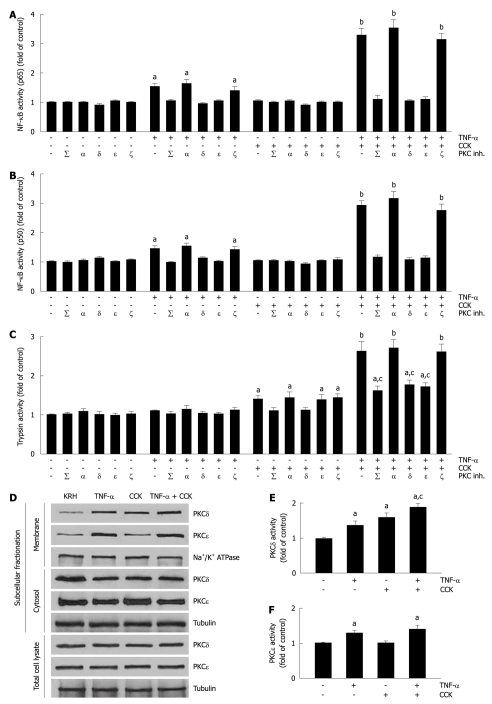

TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB is amplified by submaximal CCK

We then evaluated the activation of NF-κB (p65) and NF-κB (p50) in pancreatic acini. Previous reports established that pancreatic acinar cells respond to TNF-α by activating NF-κB in a PKCδ- and PKCε-dependent manner[22,23]. Although submaximal CCK stimulation of pancreatic acini induces the translocation and activation of PKCδ[29], this is not sufficient to activate NF-κB[29,30]. Here, we used the minimal TNF-α concentration (10 ng/mL) that we determined inhibited CCK-stimulated amylase secretion and induced actin disorganization (Figure 1A-F). Figure 2A and B show that CCK alone did not change the activity of NF-κB subunits over basal vehicle-control levels (1.03 ± 0.06 and 1.02 ± 0.05 fold of control for p65 and p50, respectively). However, TNF-α-induced an increase in the activity of both NF-κB subunits (1.52 ± 0.13 and 1.44 ± 0.11 fold of control for p65 and p50, respectively) that was amplified by CCK stimulation (3.28 ± 0.24 and 2.89 ± 0.20 fold of control for p65 and p50, respectively). Furthermore, we found that both TNF-α and TNF-α plus CCK-induced increases in the activities of NF-κB subunits were inhibited, not only by the non-specific PKC inhibitor calphostin C (iPKCΣ) (p65, 1.04 ± 0.09 and 1.12 ± 0.11 fold of control for TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively; p50, 0.98 ± 0.04 and 1.14 ± 0.11 fold of control for TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively), but by the specific PKCδ translocation inhibitor δV1-1 (iPKCδ) (p65, 0.93 ± 0.07 and 1.05 ± 0.09 fold of control for TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively; p50, 1.12 ± 0.06 and 1.04 ± 0.11 fold of control for TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively), and by the specific PKCε translocation inhibitor εV1-2 (iPKCε) (p65, 1.0 ± 0.06 and 1.12 ± 0.10 fold of control for TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively; p50, 1.00 ± 0.06 and 1.12 ± 0.10 fold of control for TNF-α and TNF-α + CCK, respectively). Neither the specific PKCα inhibitor Gö6976 (iPKCα) nor the PKCζ myristoylated pseudosubstrate inhibitor (iPKCζ) modified the changes in the activities of the NF-κB subunits induced by TNF-α or TNF-α plus CCK.

Figure 2.

Mutual modulation of tumor necrosis factor-α-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB and cholecystokinin-induced trypsin activity by submaximal cholecystokinin and tumor necrosis factor-α, respectively, involves specific protein kinase C isoforms δ and ε. A-C: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) (vehicle-control, 3 h), or in KRH (2.5 h) followed by Calphostin C (iPKCΣ, 500 nmol/L, 30 min) or Gö6976 (iPKCα, 200 nmol/L, 30 min), or with the PKCδ translocation inhibitor δV1-1 (iPKCδ, 3 h, 10 μmol/L) or the PKCε translocation inhibitor εV1-2 (iPKCε, 3 h, 10 μmol/L) or the PKCζ myristoylated pseudosubstrate inhibitor (iPKCζ, 3 h, 10 μmol/L). The acini were then stimulated with either 10 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for 2 h, or 50 pmol/L cholecystokinin (CCK) for 1 h, or 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 1 h followed by 10 ng/mL TNF-α plus 50 pmol/L CCK for 1 h, or KRH for 2 h. Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (p65) and NF-κB (p50) in nuclear extracts (A and B) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the respective assay kit. Trypsin activity (C) was measured as described in Materials and Methods. A-C: Results are expressed as fold of control and correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs KRH without inhibitors; cP < 0.05 vs TNF-α plus CCK without inhibitors; D-F: Dispersed acini were pre-incubated in KRH for 1 h and then stimulated with either 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 1.5 h, or 50 pmol/L CCK for 30 min, or 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 1 h followed by 10 ng/mL TNF-α plus 50 pmol/L CCK for 30 min, or KRH (vehicle-control) for 1.5 h; D: Subcellular fractionation showing PKCδ and ε translocation from the cytosol to the membrane upon TNF-α and/or CCK stimulation. After stimulation, acini were fractionated into membrane and cytosol fractions, and total cell lysates. 10 μg of protein of each fraction was separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the antibodies to the indicated proteins. These blots are representative of three independent experiments; E, F: PKCδ and ε activity assays. Each well was loaded with 10 μg of protein. PKCδ and ε activities were measured by ELISA using the respective assay kit. Results are expressed as fold of control and correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05 vs vehicle-control; cP < 0.05 vs either TNF-α or CCK.

TNF-α potentiates submaximal CCK-induced trypsin activity

We proceeded to analyze trypsin activity in pancreatic acini. Figure 2C shows that submaximal CCK alone only moderately increased trypsin activity (1.39 ± 0.12 fold of control), as was previously reported for submaximal cerulein[24,31,32]. While basal trypsin activity was not modified by TNF-α alone (1.09 ± 0.04 fold of control), its presence potentiated CCK-induced trypsin activity (2.63 ± 0.24 fold of control). Given that PKCδ and PKCε also modulate trypsin activity in pancreatic acinar cells[24], we further assessed trypsin activity in the presence of PKC inhibitors. We found that both CCK and TNF-α plus CCK-induced increases in trypsin activity were inhibited, not only by iPKCΣ (1.10 ± 0.09 and 1.61 ± 0.14 fold of control for CCK and TNF-α + CCK, respectively), but also by iPKCδ (1.12 ± 0.08 and 1.75 ± 0.15 fold of control for CCK and TNF-α + CCK, respectively). By contrast, iPKCε only inhibited TNF-α plus CCK-induced trypsin activity enhancement (1.38 ± 0.14 and 1.71 ± 0.12 fold of control for CCK and TNF-α + CCK, respectively). Furthermore, neither iPKCα nor iPKCζ modified the increase in trypsin activity induced by CCK or TNF-α plus CCK.

PKCδ and PKCε are translocated and activated by TNF-α plus submaximal CCK

To validate the results obtained with the specific PKC inhibitors, we examined the expression of PKCδ and PKCε in subcellular fractions from isolated pancreatic acini, as well as the respective kinase activity. Previous studies have shown that while PKCδ is translocated from cytosol to membranes and activated by both TNF-α and submaximal CCK, PKCε is only translocated and activated by TNF-α[23,29]. Here, we found similar results (1.35 ± 0.15 and 1.59 ± 0.14 fold of control for TNF-α and CCK, respectively, for PKCδ activity; 1.29 ± 0.09 and 1.02 ± 0.06 fold of control for TNF-α and CCK, respectively, for PKCε activity, Figure 2D-F). Furthermore, we showed that TNF-α plus submaximal CCK also translocated and activated both PKCδ and PKCε, significantly increasing the translocation and activation of PKCδ compared to either TNF-α or CCK alone (1.88 ± 0.12 and 1.41 ± 0.12 fold of control for TNF-α + CCK for PKCδ and PKCε, respectively, Figure 2D-F).

TNF-α does not perturb intracellular calcium oscillations induced by submaximal CCK

Both trypsinogen and NF-κB activation in pancreatic acini require not only PKC activity, but also calcium (Ca2+)[24,23,31,33]. To test the possibility that TNF-α could influence CCK activation of trypsinogen and/or NF-κB by directly affecting the Ca2+ signal, we studied the effects of TNF-α (10 ng/mL) on changes to the cytosolic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) induced by CCK (50 pmol/L) in pancreatic acini. At submaximal concentrations, CCK induced oscillatory changes in [Ca2+]i with a typical pattern consisting of base-line spikes[34]. Our results indicate that TNF-α did not affect the basal [Ca2+]i level in pancreatic acini, nor had any significant effects on the CCK-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations (data not shown).

TNF-α pus submaximal CCK induces necrosis in pancreatic acini

The process of necrosis produces damaged plasma membranes, releasing LDH into the extracellular medium. Thus, to evaluate necrosis in the present study, we measured LDH release from pancreatic acini. Figure 3A shows that unstimulated acini exhibited a 6.1% ± 0.5% LDH release, which remained relatively unchanged when acini were stimulated with TNF-α or CCK alone (6.4% ± 0.7% and 6.8% ± 0.8%, respectively). However, acini stimulated with TNF-α plus CCK showed a significant increase of 83.6% for LDH release (11.2% ± 1.1%).

Figure 3.

Tumor necrosis factor-α plus cholecystokinin induce apoptosis and necrosis in pancreatic acini. A-E: Isolated pancreatic acini were stimulated with either 10 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for 2 h, or 50 pmol/L cholecystokinin (CCK) for 1 h, or 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 1 h followed by 10 ng/mL TNF-α plus 50 pmol/L CCK for 1 h, or vehicle-control for 2 h. A: Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was measured by the DGKC optimized kinetic method using the respective assay kit. Results are expressed as a percentage of total cellular LDH determined by permeabilizing cells with Triton X-100, and correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05 vs vehicle-control; B: Caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9 activity was measured by a colorimetric/fluorometric method using the respective assay kits. Results are expressed as fold of control and correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs vehicle-control; C-E: ATP and ADP levels were measured by a bioluminescent method using the respective assay kits. ATP loss was calculated as a percentage of the decrease in values corresponding to vehicle-control. Results correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05 vs vehicle-control.

TNF-α plus submaximal CCK potentiates TNF-α-induced caspases’ activity

Subsequently, we assessed the activity of caspases in pancreatic acini. Figure 3B shows that TNF-α does augment caspases’ activity (1.22 ± 0.05, 1.25 ± 0.11, 1.24 ± 0.09 and 1.21 ± 0.08 fold of control for caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9, respectively). Although CCK alone did not change the activity of these pro-apoptotic proteins (1.02 ± 0.06, 1.03 ± 0.08, 1.04 ± 0.11 and 1.02 ± 0.06 fold of control for caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9, respectively), its combination with TNF-α further increased the activation achieved by TNF-α alone (1.93 ± 0.14, 2.14 ± 0.23, 1.87 ± 0.16 and 1.82 ± 0.19 fold of control for caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9, respectively).

TNF-α plus submaximal CCK depletes ATP and increases the ADP/ATP ratio in pancreatic acini

ATP depletion associated with the percentage of ATP loss and changes in the ADP/ATP ratio allows discrimination of apoptosis from necrosis. Thus, we analyzed ATP and ADP levels in pancreatic acini. Figure 3C shows that neither TNF-α nor CCK alone changed ATP levels compared to basal vehicle-control (10.8 ± 0.7, 11.6 ± 0.7, and 12.5 ± 0.2 μmol/mg protein for TNF-α, CCK and vehicle-control, respectively). However, TNF-α plus CCK significantly decreased ATP levels (4.3 ± 0.6 μmol/mg protein). As shown in Figure 3D, only TNF-α plus CCK significantly increased ATP loss (65.6% ± 4.8% of control), while TNF-α or CCK alone did not (13.6% ± 6.4% and 7.9% ± 5.6% of control, respectively). Figure 3E shows that only TNF-α plus CCK increased the ADP/ATP ratio over basal control (0.85 ± 0.12 vs 0.43 ± 0.01, respectively), while TNF-α or CCK alone did not (0.49 ± 0.04 and 0.46 ± 0.03, respectively).

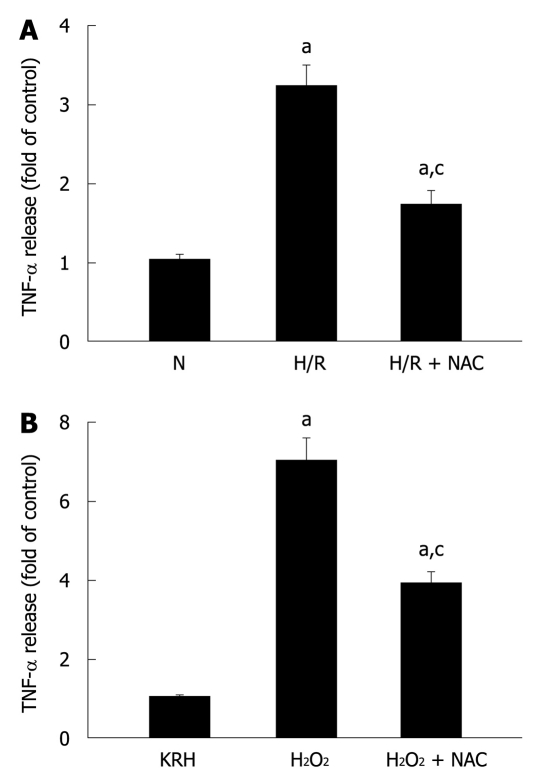

Pancreatic acinar cells secrete TNF-α in response to different stress stimuli

It is well established that pancreatic acinar cells produce TNF-α[22]. Secretion of TNF-α in response to a stressor was previously demonstrated in rat pancreatic acinar cells by their exposure to phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA)-primed neutrophils[19,20]. Here, we evaluated the response of pancreatic acini to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatments. Figure 4A and B show that both stress stimuli increased TNF-α levels (3.2 ± 0.3 and 7.0 ± 0.6 fold of control for H/R and H2O2, respectively). Incubation of acini with the specific ROS inhibitor NAC reduced TNF-α levels (1.7 ± 0.2 and 3.8 ± 0.4 fold of control for H/R and H2O2, representing a reduction of 46.9% and 45.7%, respectively), indicating that ROS mediated these stress-induced TNF-α secretions.

Figure 4.

Pancreatic acinar cells secrete tumor necrosis factor-α in response to different stressful stimuli. A: Isolated pancreatic acini were cultured in normoxic (N) conditions for 3.5 h or under hypoxia followed by normoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) for 30 min and 3 h, respectively, in the absence or presence of N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) (30 mmol/L); B: Isolated pancreatic acini were cultured in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) (vehicle-control) or stimulated with H2O2 (50 μmol/L) for 3 h in the absence or presence of NAC (30 mmol/L); A and B: TNF-α released into the supernatant was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the respective assay kit. Results are expressed as fold of control and correspond to the mean ± SE from four independent experiments, with samples performed in triplicate. aP < 0.05 vs normoxia (A) or to KRH (B); cP < 0.05 vs H/R (A) or H2O2 (B).

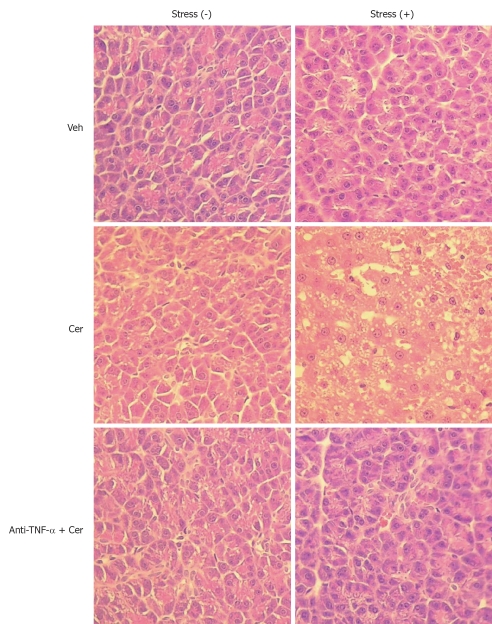

Chronic stress plus submaximal cerulein stimulation induces mild to moderate pancreatitis

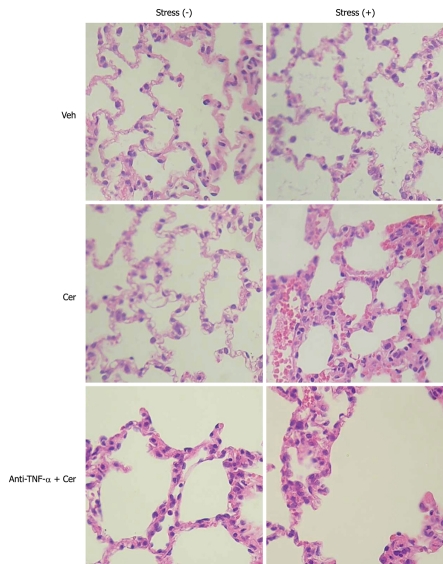

We then evaluated chronic stress plus submaximal cerulein pancreatitis in a rat model, together with an anti-TNF-α treatment as a putative therapy. First, we examined relevant serum and histological parameters of pancreatitis. Table 1 shows that Stress (+) treatment alone did not affect serum amylase and lipase levels, which were only slightly increased in the Stress (-) plus Cer group. However, this increase did not correlate with pancreatitis, which was confirmed by the completely normal pancreatic histology (Figure 5 and Table 2). In contrast, the Stress (+) plus Cer group exhibited a massive increase in serum amylase (8.4 ×) and lipase levels (85.4 ×) (Table 1) with corresponding histological changes of mild (cytoplasmic vacuoles) to moderate pancreatitis (hemorrhage, leukocyte infiltration, and necrosis) (Figure 5 and Table 2). Of particular relevance for our model, serum TNF-α was not detected in any of the Stress (-) groups (Table 1). Importantly, while TNF-α levels were detected in vehicle-control Stress (+) group, they further increased (3.5 ×) in the Stress (+) plus Cer group, which also demonstrated a marked augmentation (6.5 ×) in serum levels of LDH (Table 1). Of note, relevant serum parameters, as well as the histopathological changes found in the Stress (+) plus Cer group, were all diminished by the anti-TNF-α treatment (Figure 5, Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Relevant parameters in serum (mean ± SE)

| Group | Amylase (IU/L) | Lipase (IU/L) | TNF-α (pg/mL) | LDH (IU/L) |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | 402 ± 23 | 12 ± 2 | BD | 299 ± 21 |

| Cer | 569 ± 31 | 44 ± 3 | BD | 358 ± 23 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 572 ± 43 | 42 ± 5 | BD | 327 ± 27 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 475 ± 21 | 21 ± 3 | 12 ± 2a | 612 ± 41 |

| Cer | 3997 ± 226a | 1793 ± 118a | 42 ± 4a | 3410 ± 218a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 1895 ± 103c | 714 ± 45c | 16 ± 2c | 1534 ± 121c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. BD: Below detection limit; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Figure 5.

Chronic stress plus submaximal cerulein stimulation induces mild to moderate pancreatitis. Rats exposed to sessions of restraint (4 h every day for 21 d), Stress (+) groups, and rats in the control, Stress (-) groups, received daily intraperitoneal (ip) injections of either tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-neutralizing antibody (50 μg/kg) or control IgG. Rats were then treated with six hourly ip injections of either saline or cerulein (Cer, 0.2 μg/kg). Representative histology images of pancreatic tissue. HE, original magnification, 40 ×.

Table 2.

Histopathological score in pancreatic tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | Edema | Hemorrhage | Leukocyte infiltrate | Necrosis |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Cer | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Cer | 1.28 ± 0.11a | 3.11 ± 0.17a | 2.19 ± 0.10a | 3.12 ± 0.15a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 2.19 ± 0.17c | 1.21 ± 0.17c | 1.32 ± 0.10c | 1.37 ± 0.19c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

We then analyzed inflammatory parameters in pancreatic tissue. The results are shown in Table 3. As was observed in serum, pancreatic TNF-α was only detected in the Stress (+) groups, where the levels were further increased (3.4 ×) in the Cer subgroup, and were diminished by 63% by the anti-TNF-α treatment. Remarkably, HIF-1α showed a similar trend, being only detected in the Stress (+) groups, where the levels were further increased (4 ×) in the Cer subgroup, and diminished by 58% by the anti-TNF-α treatment. Other assessed parameters (active trypsin, NF-κB (p65) and (p50), MPO, LPO, and MDA) also exhibited increased values in the Stress (+) plus Cer group, which were reduced by the anti-TNF-α treatment.

Table 3.

Inflammatory parameters in pancreatic tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | TNF-α (ng/mg DNA) | HIF-1α (ng/mg DNA) | Active trypsin (nmol/mg DNA) | NF-κB (p65) (μg/mg DNA) | NF-κB (p50) (μg/mg DNA) | MPO (U/mg DNA) | LPO (nmol/mg DNA) | MDA (μmol/mg DNA) |

| Stress (-) | ||||||||

| Veh | BD | BD | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 43 ± 5 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | BD | 0.71 ± 0.03 |

| Cer | BD | BD | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 46 ± 6 | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | BD | 0.89 ± 0.05 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | BD | BD | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 44 ± 3 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | BD | 0.84 ± 0.05 |

| Stress (+) | ||||||||

| Veh | 1.6 ± 0.2a | 0.9 ± 0.1a | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 72 ± 6 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 1.41 ± 0.07 | 27 ± 2 | 2.05 ± 0.11 |

| Cer | 5.4 ± 0.3a | 3.6 ± 0.3a | 4.15 ± 0.32a | 389 ± 25a | 5.54 ± 0.35a | 15.90 ± 0.66a | 316 ± 20a | 22.16 ± 0.69a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 2.0 ± 0.2c | 1.5 ± 0.3c | 1.79 ± 0.21c | 221 ± 18c | 2.65 ± 0.24c | 7.14 ± 0.38c | 171 ± 14c | 12.38 ± 0.47c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. BD: Below detection limit; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; HIF-1α: Hypoxia inducible factor-1α; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB; MPO: Myeloperoxidase; LPO: Lipid hydroperoxide; MDA: Malondialdehyde.

We also evaluated inflammatory and general biochemical parameters in blood. As shown in Table 4, all the studied inflammatory parameters (leukocyte number, C-reactive protein, HSP-72, IL-6, IL-10, and MIP-1α) were increased in the Stress (+) plus Cer group, whose values correlated with mild to moderate pancreatitis. Importantly, these elevated values were all attenuated by the anti-TNF-α treatment. Furthermore, Table 5 shows that the studied biochemical parameters (glucose, urea, creatinine, calcium, proteins, AST, ALT, and hematocrit) also evidenced alterations compatible with mild to moderate pancreatitis in the Stress (+) plus Cer group, which were mitigated in the Stress (+) plus anti-TNF-α plus Cer group.

Table 4.

Inflammatory parameters in blood (mean ± SE)

| Group | Leukocytes (ng/mL) | CRP (mg/dL) | HSP-72 (pg/mL) | IL-6 (pg/mL) | IL-10 (pg/mL) | MIP-1α (pg/mL) |

| Stress (-) | ||||||

| Veh | 5900 ± 240 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 558 ± 27 | BD | BD | 7 ± 1 |

| Cer | 6111 ± 248 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 866 ± 32 | BD | BD | 9 ± 1 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 6005 ± 244 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 817 ± 49 | BD | BD | 8 ± 1 |

| Stress (+) | ||||||

| Veh | 7139 ± 250 | 1.5 ± 0.2a | 899 ± 63 | 66 ± 6a | 75 ± 5a | 54 ± 4a |

| Cer | 21 222 ± 976a | 24.9 ± 1.3a | 2648 ± 159a | 1115 ± 54a | 1404 ± 148a | 318 ± 23a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 12 733 ± 586c | 12.4 ± 0.8c | 1805 ± 112c | 417 ± 38c | 596 ± 68c | 127 ± 11b |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. CRP: C-reactive protein; HSP: Heat shock protein; IL: Interleukin; MIP-1α: Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; BD: Below detection limit.

Table 5.

General biochemical assays in blood (mean ± SE)

| Group | Glucose (mg/dL) | Urea (mg/dL) | Creatinine (mg/dL) | Calcium (mg/dL) | Proteins (g/dL) | AST (IU/L) | ALT (IU/L) | Hematocrit (%) |

| Stress (-) | ||||||||

| Veh | 139 ± 13 | 39 ± 4 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 13.02 ± 0.57 | 8.51 ± 0.39 | 192 ± 21 | 88 ± 7 | 40 ± 5 |

| Cer | 153 ± 14 | 55 ± 4 | 0.65 ± 0.09 | 11.08 ± 0.48 | 7.46 ± 0.28 | 298 ± 32 | 155 ± 14 | 42 ± 4 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 148 ± 12 | 52 ± 5 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 10.91 ± 0.70 | 7.51 ± 0.43 | 293 ± 20 | 149 ± 9 | 41 ± 5 |

| Stress (+) | ||||||||

| Veh | 118 ± 11a | 38 ± 5 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 11.72 ± 0.61 | 8.48 ± 0.22 | 201 ± 26 | 95 ± 9 | 36 ± 5a |

| Cer | 294 ± 26a | 105 ± 9a | 1.94 ± 0.50a | 9.03 ± 0.33a | 6.02 ± 0.19a | 432 ± 35a | 219 ± 19a | 41 ± 3 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 189 ± 16c | 73 ± 8c | 1.14 ± 0.24c | 9.63 ± 0.58 | 6.76 ± 0.35c | 356 ± 29c | 187 ± 19c | 39 ± 4 |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

As performed for isolated pancreatic acini, we then investigated pancreatic caspases and energy metabolism in pancreatic tissue. Table 6 shows that caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9 were only augmented in the Stress (+) groups. These values were further increased (6-8 ×) in the Cer subgroup, and diminished by between 21%-37% by the anti-TNF-α treatment. Table 7 shows that the Stress (+) plus Cer group experienced a severe decrease in ATP content (> 70%) and a significant increase in the ADP/ATP ratio (3 ×). Both ATP loss and the ADP/ATP ratio were partially restored by the anti-TNF-α treatment.

Table 6.

Pancreatic caspases (mean ± SE)

| Group | CASP-2 | CASP-3 | CASP-8 | CASP-9 |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | 34 ± 6 | 25 ± 2 | 45 ± 5 | 40 ± 7 |

| Cer | 56 ± 12 | 63 ± 9 | 87 ± 11 | 82 ± 8 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 50 ± 7 | 39 ± 5 | 72 ± 7 | 68 ± 9 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 124 ± 15 | 118 ± 10 | 189 ± 11 | 158 ± 16 |

| Cer | 995 ± 88a | 838 ± 74a | 1123 ± 103a | 1079 ± 70a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 696 ± 47c | 544 ± 58c | 887 ± 65c | 679 ± 48c |

Pancreatic caspases are expressed as pmol/min per milligram protein.

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; CASP: Caspase.

Table 7.

Energy metabolism in pancreatic tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | ATP (μmol/mg protein) | ATP loss (%) | ADP/ATP ratio |

| Stress (-) | |||

| Veh | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 4.4 | 0.32 ± 0.04 |

| Cer | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 25.3 ± 5.5 | 0.38 ± 0.05 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 24.2 ± 6.6 | 0.36 ± 0.04 |

| Stress (+) | |||

| Veh | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 19.8 ± 5.5 | 0.40 ± 0.06 |

| Cer | 2.6 ± 0.4a | 71.4 ± 4.4a | 0.94 ± 0.11a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 5.3 ± 0.3c | 41.8 ± 3.3c | 0.63 ± 0.07c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Chronic stress plus submaximal cerulein stimulation induces pancreatitis-associated lung injury

A common, and often fatal, systemic complication of acute pancreatitis is acute lung injury, which frequently evolves to acute respiratory distress syndrome[35]. To evaluate this, we examined histological and inflammatory parameters in lung tissue. Figure 6 and Tables 8 and 9 show that histopathological parameters (edema, hemorrhage, and leukocyte infiltrate, Figure 6 and Table 8) as well as MPO, NF-κB (p65), and (p50) (Table 9) were uniformly normal in all Stress (-) groups. In contrast, the Stress (+) plus Cer group exhibited histopathological and inflammatory changes compatible with pancreatitis-associated lung injury (Figure 6, Tables 8 and 9). As was observed in pancreatic tissue, TNF-α levels were only detected in the Stress (+) groups, with increased values in the Cer subgroup (3 ×), which were attenuated by 57% by the anti-TNF-α treatment (Table 9).

Figure 6.

Chronic stress plus submaximal cerulein stimulation induces pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Rats exposed to sessions of restraint (4 h every day for 21 d), Stress (+) groups, and rats in the control, Stress (-) groups, received daily intraperitoneal (ip) injections of either tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-neutralizing antibody (50 μg/kg) or control IgG, rats were then treated with six hourly ip injections of either saline or cerulein (Cer, 0.2 μg/kg). Representative histology images of lung tissue. HE, original magnification, 40 ×.

Table 8.

Histopathological score in lung tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | Edema | Hemorrhage | Leukocyte infiltrate |

| Stress (-) | |||

| Veh | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Cer | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Stress (+) | |||

| Veh | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.30 ± 0.03 |

| Cer | 1.51 ± 0.11a | 2.73 ± 0.58a | 1.63 ± 0.54a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 1.80 ± 0.21c | 1.21 ± 0.08c | 0.73 ± 0.05c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Table 9.

Inflammatory parameters in lung tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | TNF-α (ng/mg DNA) | MPO (U/mg DNA) | NF-κB (p65) (μg/mg DNA) | NF-κB (p50) (μg/mg DNA) |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | BD | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 23 ± 2 | 0.27 ± 0.02 |

| Cer | BD | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 24 ± 2 | 0.30 ± 0.02 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | BD | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 24 ± 3 | 0.29 ± 0.03 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 1.3 ± 0.1a | 0.89 ± 0.12 | 43 ± 5 | 0.51 ± 0.03 |

| Cer | 4.2 ± 0.3a | 12.10 ± 0.56a | 251 ± 19a | 2.92 ± 0.28a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 1.8 ± 0.2c | 5.04 ± 0.29c | 107 ± 9c | 1.13 ± 0.11c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; MPO: Myeloperoxidase; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB.

Additionally, we measured caspases’ activity and energy metabolism in lung tissue. The results are presented in Tables 10 and 11, respectively. As it was found for pancreatic tissue (Tables 6 and 7), caspases 2, 3, 8, and 9 were only augmented in the Stress (+) groups. These values were further increased (8-9 ×) in the Cer subgroup, and diminished between 30%-38% by the anti-TNF-α treatment (Table 10). Table 11 shows that the Stress (+) plus Cer group experienced a severe decrease in ATP content (> 65%) and a significant increase in the ADP/ATP ratio (4 ×). Here, the ATP loss and the ADP/ATP ratio were also partially restored by the anti-TNF-α treatment.

Table 10.

Lung caspases (mean ± SE)

| Group | CASP-2 | CASP-3 | CASP-8 | CASP-9 |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | 18 ± 3 | 20 ± 2 | 21 ± 5 | 22 ± 4 |

| Cer | 27 ± 3 | 29 ± 4 | 32 ± 5 | 29 ± 3 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 26 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 24 ± 4 | 22 ± 3 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 97 ± 11 | 103 ± 9 | 99 ± 8 | 104 ± 12 |

| Cer | 853 ± 81a | 912 ± 101a | 824 ± 77a | 917 ± 85a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 597 ± 48c | 592 ± 55c | 560 ± 45c | 568 ± 47c |

Lung caspases are expressed as pmol/min per milligram protein.

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; CASP: Caspase.

Table 11.

Energy metabolism in lung tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | ATP (μmol/mg protein) | ATP loss (%) | ADP/ATP ratio |

| Stress (-) | |||

| Veh | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 4.9 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| Cer | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 2.9 | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 10.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 3.8 | 0.21 ± 0.03 |

| Stress (+) | |||

| Veh | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 25.5 ± 6.8 | 0.32 ± 0.05 |

| Cer | 3.6 ± 0.4a | 66.0 ± 3.8a | 0.72 ± 0.10a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 6.7 ± 0.6c | 36.8 ± 5.7c | 0.49 ± 0.06c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Chronic stress induces gastric lesions

In the general adaptation syndrome described by Selye, the first lesions to appear as a result of stress were found in the stomach. To corroborate that the protocol we have used in our model produces stress, we evaluated histopathological changes together with apoptotic/necrotic parameters in stomach tissue. Tables 12, 13 and 14 show that our protocol of restraint was effective in generating stress in rats.

Table 12.

Histopathological score in stomach tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | Edema | Hemorrhage | Leukocyte infiltrate | Necrosis |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Cer | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 3.25 ± 0.14b | 1.55 ± 0.08a | 1.26 ± 0.19a | 0.95 ± 0.06a |

| Cer | 1.17 ± 0.08a | 3.23 ± 0.29a | 2.77 ± 0.16a | 3.48 ± 0.32a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 1.96 ± 0.17c | 2.23 ± 0.15c | 1.63 ± 0.05c | 1.57 ± 0.12c |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Table 13.

Stomach caspases (mean ± SE)

| Group | CASP-2 | CASP-3 | CASP-8 | CASP-9 |

| Stress (-) | ||||

| Veh | 37 ± 4 | 32 ± 3 | 48 ± 5 | 39 ± 5 |

| Cer | 40 ± 5 | 32 ± 5 | 51 ± 4 | 40 ± 3 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 33 ± 4 | 30 ± 3 | 47 ± 4 | 39 ± 4 |

| Stress (+) | ||||

| Veh | 1358 ± 132a | 1515 ± 154a | 1479 ± 136a | 1425 ± 126a |

| Cer | 798 ± 87a | 824 ± 95a | 868 ± 70a | 832 ± 87a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 1089 ± 98c | 1203 ± 107c | 1108 ± 89c | 1144 ± 102c |

Stomach caspases are expressed as pmol/min per milligram protein.

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; CASP: Caspase.

Table 14.

Energy metabolism in stomach tissue (mean ± SE)

| Group | ATP (μmol/mg protein) | ATP loss (%) | ADP/ATP ratio |

| Stress (-) | |||

| Veh | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 6.7 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| Cer | 12.9 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 5.2 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 13.0 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 6.0 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| Stress (+) | |||

| Veh | 5.5 ± 0.4a | 58.9 ± 3.0a | 0.67 ± 0.07a |

| Cer | 2.3 ± 0.4a | 82.8 ± 3.0a | 1.14 ± 0.16a |

| Anti-TNF-α + Cer | 6.2 ± 0.6c | 53.7 ± 4.5c | 0.58 ± 0.06c |

P < 0.05 vs control-vehicle Stress (-) group;

P < 0.05 vs Stress (+) plus Cer group. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

DISCUSSION

Although oxidative stress and inflammation each occur in the pancreas during the early stage of supramaximal cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis, oxidative stress or an inflammatory insult alone does not cause the characteristic changes of acute pancreatitis[36]. However, our present study demonstrates that chronic stress leaves the exocrine pancreas susceptible to pancreatitis by submaximal cerulein stimulation.

The main events occurring in the pancreatic acinar cell that initiate and propagate acute pancreatitis include inhibition of secretion, intracellular activation of proteases, and generation of inflammatory mediators[37]. These cellular events can be correlated with the acinar morphological changes (retention of enzyme content, formation of large vacuoles containing both digestive enzymes and lysosomal hydrolases, and necrosis), which are observed in the well-established in vivo experimental model of supraphysiological cerulein-induced pancreatitis[38], as well as in human acute pancreatitis[39].

Here, we employed a new model of chronic stress plus submaximal cerulein stimulation to induce pancreatitis. Furthermore, we studied a new in vitro model of TNF-α plus submaximal CCK stimulation, and obtained results that not only reproduced the main pathological events experienced by the acinar cell, but also support the pancreatitis observed in animals exposed to the in vivo model.

First, we established that the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α inhibits submaximal CCK-stimulated amylase secretion from pancreatic acini. While TNF-α alone does not stimulate amylase secretion in human pancreas[40] or in isolated rat pancreatic acini, it certainly alters the typical filamentous actin distribution[21]. A similar redistribution of actin from apical to basolateral membranes was observed in pancreatic acini supra-stimulated with CCK[41]. Disorganization of the actin cytoskeleton is associated with dysregulation of pancreatic enzyme secretion[42], which could explain our findings (Figure 1).

Although necessary, the inhibition of pancreatic enzyme secretion alone is not sufficient to induce pancreatitis[37]. Nonetheless, we also demonstrated that the combination of TNF-α and submaximal CCK pathologically activates NF-κB and trypsinogen in pancreatic acini. TNF-α has been shown to regulate the activity of distinct PKC isoforms in diverse cell types, including the pancreatic acinar cell[23,43,44]. PKC consists of a family of at least 12 isozymes differing in tissue distribution and activation requirements. There are three subclasses: classical PKC isozymes (-α, -β1, -β2, and -γ), which require calcium and are activated by diacylglycerol and phorbol ester; the novel PKC isozymes (-δ, -ε, -η, and -θ), which are activated by diacylglycerol and phorbol ester independently of calcium; and the atypical PKC isozymes (-λ, -ι, and -ζ), which are calcium independent and not responsive to phorbol ester. Rat pancreatic acini express the α, δ, ε, and ζ PKC isozymes[45]. Changes in PKC activity are associated with inflammation in a variety of tissues, including skin, kidney, intestine, and pancreas[46-49]. Specifically, PKC-δ and PKC-ε regulate the signal transduction pathways implicated in the pathophysiological activation of NF-κB and trypsinogen in pancreatic acini[23,24]. TNF-α activates both PKC-δ and PKC-ε in pancreatic acini[23], and our study shows that in turn, these convert physiological CCK concentrations into physiopathogenic concentrations (Figure 2). Different studies have consistently shown that modulation of PKC activity sensitizes acinar cells to physiological CCK and cerulein treatments, resulting in harmful levels of NF-κB and trypsin activity, respectively[29,24]. In agreement with TNF-α-regulated functions[11] and the above discussed results, we found that TNF-α plus submaximal CCK induced both apoptosis and necrosis in acinar cells, as revealed by the increased caspases’ activity, increased LDH release, ATP loss, and changes in the ADP/ATP ratio (Figure 3).

Secretion of TNF-α by several stress stimuli has been demonstrated in vitro in many cell types, including pancreatic acinar cells[13-20], and in vivo in different tissues[10,12,50,51]. We have shown that in vitro hypoxia-reoxygenation conditions also induce TNF-α secretion by acinar cells (Figure 4). These conditions are concomitant with ischemia-reperfusion processes, which can be the result of microcirculatory disturbances generated by stress[52]. Indeed, local pancreatic blood flow is reduced by stress[53]. Hence, alternate vasoconstriction and vasodilatation leading to tissue ischemia and reperfusion could reflect the putative local origin of chronic stress-derived TNF-α found in the rat exocrine pancreas, which is supported by the increased levels of HIF-1α observed in the Stress (+) groups (Figure 5, Tables 1-3). HIF-1α is a transcription factor induced by hypoxic conditions and is involved in different inflammatory processes, such as dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis[54], and also pancreatitis[55].

Our model of chronic stress plus submaximal doses of cerulein produced the hallmark features of pancreatitis (Figure 5, Tables 1-5), and also of its most frequent complication, pancreatitis-associated lung injury (Figure 6, Tables 8 and 9), which characterizes the severity of this disease[34]. Importantly, treatment with a TNF-α antibody greatly protected rats from chronic stress-related pancreatitis (Figures 5 and 6, Tables 1-5, 8 and 9). These results strongly suggest a causative role for TNF-α in the development of pancreatitis induced in chronically stressed animals.

Although anti-TNF-α therapy decreased pancreatitis severity, animals still developed a very-mild form of this disease. The limited protection achieved in vivo was probably due to a multiplicity of factors involved in the development of pancreatitis, some of which seem to act independent of TNF-α. Further work will be required to identify the additional molecules and signaling pathways involved in chronic stress as a contributing factor to pancreatitis. Nevertheless, this initial work demonstrates a novel susceptibility mechanism by which chronic stress could predispose the exocrine pancreas to pancreatitis triggered by physiological levels of cerulein stimulation.

COMMENTS

Background

Pancreatitis is an inflammatory disorder of the pancreas characterized by premature activation of pancreatic enzymes leading to pancreatic autodigestion, persistent inflammation, edema, and possible pancreatic necrosis. A wide variety of factors, including gallstones, alcoholism, and a complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of this disease.

Research frontiers

Initial inflammation of the pancreas may progress to involve other organs such as the kidney, lungs, and liver. Inflammatory mediators induce complications that can range from local to systemic, leading to a severe form with high morbidity/mortality. Thus, it is critical to identify the precipitating factors of pancreatitis, because treatment will diverge significantly depending on the etiology.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Chronic stress has received little attention as a factor contributing to pancreatitis. Using a new model combining chronic restraint and physiological stimulation of the exocrine pancreas, the authors have established that chronic stress might sensitize the pancreas to pancreatitis. Furthermore, they have begun to elucidate the molecules responsible for the initial events.

Applications

The protective effect shown by anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in this experimental model of pancreatitis indicates a potential clinical application for this antibody in treating this disease. However, the results also indicate that other molecules might be involved in this pathology. This suggests that better results could be obtained by combined therapies, but this requires further experiments to identify additional key contributing molecules.

Peer review

The authors present a study that demonstrates that chronic stress enhances the susceptibility for pancreatic damage produced by physiological cerulein stimulation. It is thought that the authors have produced a good piece of work.

Footnotes

Supported by KB Certification International

Peer reviewer: José Julián calvo Andrés, Department of Physiolgy and Pharmacology, University of Salamanca, Edificio Departamentl, Plaza de los Doctores de la Reina, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Sternberg EM, Chrousos GP, Wilder RL, Gold PW. The stress response and the regulation of inflammatory disease. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:854–866. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-10-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen JH, Wei SZ, Chen J, Wang Q, Liu HL, Gao XH, Li GC, Yu WZ, Chen M, Luo HS. Sensory denervation reduces visceral hypersensitivity in adult rats exposed to chronic unpredictable stress: evidences of neurogenic inflammation. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1884–1891. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takács T, Rakonczay Z Jr, Varga IS, Iványi B, Mándi Y, Boros I, Lonovics J. Comparative effects of water immersion pretreatment on three different acute pancreatitis models in rats. Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;80:241–251. doi: 10.1139/o02-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosen-Binker LI, Binker MG, Negri G, Tiscornia O. Influence of stress in acute pancreatitis and correlation with stress-induced gastric ulcer. Pancreatology. 2004;4:470–484. doi: 10.1159/000079956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harada E, Kanno T. Progressive enhancement in the secretory functions of the digestive system of the rat in the course of cold acclimation. J Physiol. 1976;260:629–645. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harada E. Lowering of pancreatic amylase activity induced by cold exposure, fasting and adrenalectomy in rats. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1991;98:333–338. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(91)90542-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colón AL, Madrigal JL, Menchén LA, Moro MA, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Leza JC. Stress increases susceptibility to oxidative/nitrosative mucosal damage in an experimental model of colitis in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1713–1721. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000043391.64073.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Pablos RM, Villarán RF, Argüelles S, Herrera AJ, Venero JL, Ayala A, Cano J, Machado A. Stress increases vulnerability to inflammation in the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5709–5719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0802-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munhoz CD, García-Bueno B, Madrigal JL, Lepsch LB, Scavone C, Leza JC. Stress-induced neuroinflammation: mechanisms and new pharmacological targets. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2008;41:1037–1046. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2008001200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu H, Tang C, Peng K, Sun H, Yang Y. Effects of chronic mild stress on the development of atherosclerosis and expression of toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway in adolescent apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:613879. doi: 10.1155/2009/613879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu ZG. Molecular mechanism of TNF signaling and beyond. Cell Res. 2005;15:24–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzon E, Cuzzocrea S. Role of TNF-alpha in ileum tight junction alteration in mouse model of restraint stress. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1268–G1280. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00014.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong W, Simeonova PP, Gallucci R, Matheson J, Flood L, Wang S, Hubbs A, Luster MI. Toxic metals stimulate inflammatory cytokines in hepatocytes through oxidative stress mechanisms. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;151:359–366. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbs BF, Wierecky J, Welker P, Henz BM, Wolff HH, Grabbe J. Human skin mast cells rapidly release preformed and newly generated TNF-alpha and IL-8 following stimulation with anti-IgE and other secretagogues. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:312–320. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang JY, Wang JY. Hypoxia/Reoxygenation induces nitric oxide and TNF-alpha release from cultured microglia but not astrocytes of the rat. Chin J Physiol. 2007;50:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang BW, Hung HF, Chang H, Kuan P, Shyu KG. Mechanical stretch enhances the expression of resistin gene in cultured cardiomyocytes via tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2305–H2312. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00361.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HG, Kim JY, Gim MG, Lee JM, Chung DK. Mechanical stress induces tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} production through Ca2+ release-dependent TLR2 signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C432–C439. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00085.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Xia Q, Zhang Q, Li H, Zhang J, Li A, Xiu R. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 and pioglitazone inhibit hydroxyl peroxide-induced TNF-alpha and lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine expression in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Shock. 2009;32:317–324. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31819c374c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H, Seo JY, Roh KH, Lim JW, Kim KH. Suppression of NF-kappaB activation and cytokine production by N-acetylcysteine in pancreatic acinar cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:674–683. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo JY, Kim H, Seo JT, Kim KH. Oxidative stress induced cytokine production in isolated rat pancreatic acinar cells: effects of small-molecule antioxidants. Pharmacology. 2002;64:63–70. doi: 10.1159/000056152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh A, Gukovskaya AS, Edderkaoui M, Daghighian MS, Reeve JR Jr, Shimosegawa T, Pandol SJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates pancreatitis responses in acinar cells via protein kinase C and proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:639–651. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gukovskaya AS, Gukovsky I, Zaninovic V, Song M, Sandoval D, Gukovsky S, Pandol SJ. Pancreatic acinar cells produce, release, and respond to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Role in regulating cell death and pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1853–1862. doi: 10.1172/JCI119714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satoh A, Gukovskaya AS, Nieto JM, Cheng JH, Gukovsky I, Reeve JR Jr, Shimosegawa T, Pandol SJ. PKC-delta and -epsilon regulate NF-kappaB activation induced by cholecystokinin and TNF-alpha in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G582–G591. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00087.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thrower EC, Osgood S, Shugrue CA, Kolodecik TR, Chaudhuri AM, Reeve JR Jr, Pandol SJ, Gorelick FS. The novel protein kinase C isoforms -delta and -epsilon modulate caerulein-induced zymogen activation in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1344–G1353. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00020.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makhija R, Kingsnorth AN. Cytokine storm in acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s005340200049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schultz GS, Sarras MP Jr, Gunther GR, Hull BE, Alicea HA, Gorelick FS, Jamieson JD. Guinea pig pancreatic acini prepared with purified collagenase. Exp Cell Res. 1980;130:49–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernfeld P. Enzymes of starch degradation and synthesis. Adv Enzymol Relat Subj Biochem. 1951;12:379–428. doi: 10.1002/9780470122570.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cosen-Binker LI, Binker MG, Cosen R, Negri G, Tiscornia O. Relaxin prevents the development of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1558–1568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i10.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh A, Gukovskaya AS, Reeve JR Jr, Shimosegawa T, Pandol SJ. Ethanol sensitizes NF-kappaB activation in pancreatic acinar cells through effects on protein kinase C-epsilon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G432–G438. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00579.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gukovskaya AS, Hosseini S, Satoh A, Cheng JH, Nam KJ, Gukovsky I, Pandol SJ. Ethanol differentially regulates NF-kappaB activation in pancreatic acinar cells through calcium and protein kinase C pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G204–G213. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00088.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saluja AK, Bhagat L, Lee HS, Bhatia M, Frossard JL, Steer ML. Secretagogue-induced digestive enzyme activation and cell injury in rat pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G835–G842. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhoomagoud M, Jung T, Atladottir J, Kolodecik TR, Shugrue C, Chaudhuri A, Thrower EC, Gorelick FS. Reducing extracellular pH sensitizes the acinar cell to secretagogue-induced pancreatitis responses in rats. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1083–1092. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tando Y, Algül H, Wagner M, Weidenbach H, Adler G, Schmid RM. Caerulein-induced NF-kappaB/Rel activation requires both Ca2+ and protein kinase C as messengers. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G678–G686. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.3.G678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yule DI, Lawrie AM, Gallacher DV. Acetylcholine and cholecystokinin induce different patterns of oscillating calcium signals in pancreatic acinar cells. Cell Calcium. 1991;12:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(91)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saluja AK, Bhagat L. Pancreatitis and associated lung injury: when MIF miffs. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:844–847. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu K, Sarras MP Jr, De Lisle RC, Andrews GK. Expression of oxidative stress-responsive genes and cytokine genes during caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G696–G705. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.3.G696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaisano HY, Gorelick FS. New insights into the mechanisms of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2040–2044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lampel M, Kern HF. Acute interstitial pancreatitis in the rat induced by excessive doses of a pancreatic secretagogue. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1977;373:97–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00432156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klöppel G, Dreyer T, Willemer S, Kern HF, Adler G. Human acute pancreatitis: its pathogenesis in the light of immunocytochemical and ultrastructural findings in acinar cells. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;409:791–803. doi: 10.1007/BF00710764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denham W, Yang J, Fink G, Denham D, Carter G, Bowers V, Norman J. TNF but not IL-1 decreases pancreatic acinar cell survival without affecting exocrine function: a study in the perfused human pancreas. J Surg Res. 1998;74:3–7. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schäfer C, Ross SE, Bragado MJ, Groblewski GE, Ernst SA, Williams JA. A role for the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Hsp 27 pathway in cholecystokinin-induced changes in the actin cytoskeleton in rat pancreatic acini. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24173–24180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torgerson RR, McNiven MA. The actin-myosin cytoskeleton mediates reversible agonist-induced membrane blebbing. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 19):2911–2922. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kilpatrick LE, Sun S, Mackie D, Baik F, Li H, Korchak HM. Regulation of TNF mediated antiapoptotic signaling in human neutrophils: role of delta-PKC and ERK1/2. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1512–1521. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang Q, Tepperman BL. Effect of selective PKC isoform activation and inhibition on TNF-alpha-induced injury and apoptosis in human intestinal epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:41–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pollo DA, Baldassare JJ, Honda T, Henderson PA, Talkad VD, Gardner JD. Effects of cholecystokinin (CCK) and other secretagogues on isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC) in pancreatic acini. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1224:127–138. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breitkreutz D, Braiman-Wiksman L, Daum N, Denning MF, Tennenbaum T. Protein kinase C family: on the crossroads of cell signaling in skin and tumor epithelium. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:793–808. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0280-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raptis AE, Viberti G. Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001;109 Suppl 2:S424–S437. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fasano A. Regulation of intercellular tight junctions by zonula occludens toxin and its eukaryotic analogue zonulin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;915:214–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi C, Zhao X, Wang X, Zhao L, Andersson R. Potential effects of PKC or protease inhibitors on acute pancreatitis-induced tissue injury in rats. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007;46:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munhoz C, Madrigal JL, García-Bueno B, Pradillo JM, Moro MA, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Scavone C, Leza JC. TNF-alpha accounts for short-term persistence of oxidative status in rat brain after two weeks of repeated stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1125–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pavlovic S, Daniltchenko M, Tobin DJ, Hagen E, Hunt SP, Klapp BF, Arck PC, Peters EM. Further exploring the brain-skin connection: stress worsens dermatitis via substance P-dependent neurogenic inflammation in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:434–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopylova GN, Smirnova EA, Sanzhieva LTs, Umarova BA, Lelekova TV, Samonina GE. Glyprolines and semax prevent stress-induced microcirculatory disturbances in the mesentery. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2003;136:441–443. doi: 10.1023/b:bebm.0000017087.90585.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Furukawa M, Kimura T, Sumii T, Yamaguchi H, Nawata H. Role of local pancreatic blood flow in development of hemorrhagic pancreatitis induced by stress in rats. Pancreas. 1993;8:499–505. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199307000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, Förster I, Pawlinski R, Mackman N, Haase VH, Jaenisch R, Corr M, Nizet V, et al. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112:645–657. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomez G, Englander EW, Wang G, Greeley GH Jr. Increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, p48, and the Notch signaling cascade during acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2004;28:58–64. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]